Introduction and summary

In the past few decades, much of the national policy discourse on NHS organisations that provide health care in England has focused on how they perform against a core set of quality and financial targets. The policy focus has been on deploying a range of regulatory and payment levers to try to ensure compliance with these targets, or pursuing structural reform to boost performance and tackle variation between providers. As a result, much more attention has been paid to ‘what’ providers have done than to ‘how’ or ‘why’ they have done it, and much more emphasis has been placed on externally driven, rather than internally driven, change.

In recent years, however, there have been signs of a shift in approach. National frameworks and concordats such as Developing People, Improving Care and Shared Commitment to Quality have looked beyond performance metrics to the capabilities and capacity needed within provider organisations to drive improvement. It is important to measure, recognise and incentivise quality, these documents argue, but this must go hand in hand with a strategy for providers to build the knowledge, skills and infrastructure that are needed for the consistent delivery of high-quality care and for continuous improvement. Similarly, the Care Quality Commission’s (CQC) examination of how NHS trusts rated as outstanding have embedded quality improvement (QI) across their organisations highlights the importance of building the right skills and culture among staff.

The NHS long term plan recognises that successful delivery ‘will rely on local health systems having the capability to implement change effectively’ and commits to ‘supporting service improvement and transformation across systems and within providers’. This includes an initiative, in partnership with the Health Foundation, to increase the number of integrated care systems that are building improvement capability.

This report summarises the evidence on building improvement capability to support this evolving agenda, primarily within the context of the NHS in England. It draws on the learning and insights that the Health Foundation has generated over the past 15 years from funding and evaluating improvement at team, organisation and system level.

Part I describes what is meant by an organisational approach to improvement and why it matters. An organisation-wide approach can ensure that local activities are aligned, coordinated and appropriately resourced, helping to avoid the fragmentation and duplication often associated with working only at the microsystem level. It also provides the strategic constancy of purpose, momentum and infrastructure necessary for multifaceted, cross-organisational initiatives to emerge.

Most of the NHS trusts in England that have an outstanding CQC rating have implemented an organisational approach to improvement. Part I also provides case studies of three of these trusts: East London NHS Foundation Trust, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

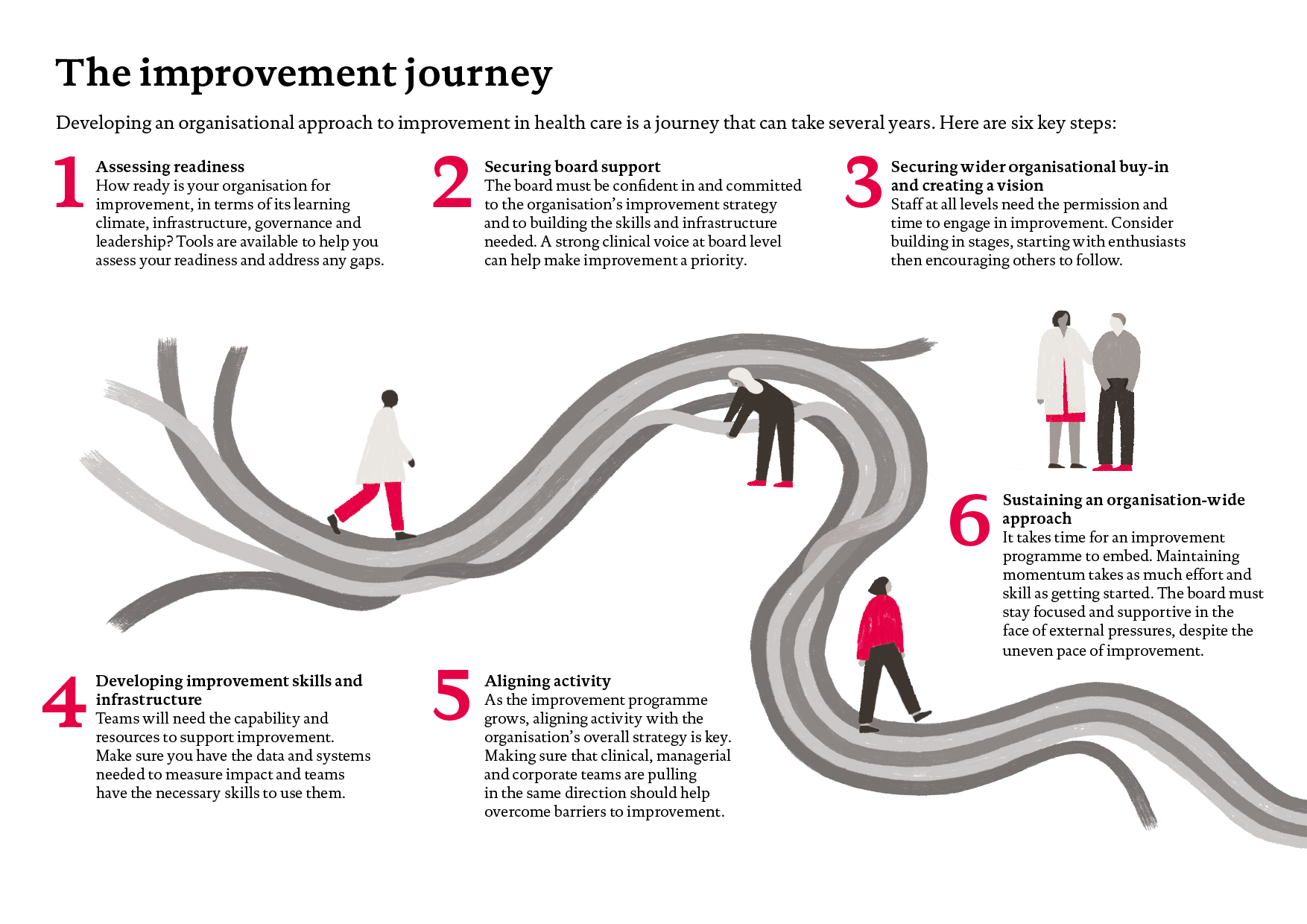

Part II describes the six steps of the improvement journey that trusts must go on to put in place an organisation-wide approach:

- assessing readiness

- securing board support

- securing wider organisational buy-in and creating a vision

- developing improvement skills and infrastructure

- aligning and coordinating activity

- sustaining an organisation-wide approach.

It also sets out the different approaches trusts can take to building their capability: building ‘from within’; seeking support from commercial and not-for-profit bodies and consultants; and seeking support from peer organisations. In addition, it outlines some investment considerations.

Drawing on analysis of peer-reviewed improvement literature and the Health Foundation’s own improvement programmes and publications, Part II also sets out the enabling factors that contribute to the success of an organisational approach. These fall into four broad categories: leadership and governance; infrastructure and resources; skills and workforce; and culture and environment. It further describes some of the key organisational barriers to improvement.

Part III describes recent approaches that national bodies in England have taken to support and encourage the building of improvement capability, and looks at how what is required to make further progress. Ultimately, providers and local health and care systems themselves are responsible for taking forward this agenda, though policymakers and system leaders have an important responsibility in supporting them to do so.

National bodies with regulatory, performance-management or support responsibilities should speak with one voice about organisational improvement and develop a shared model of change. They should also do more to encourage and support organisations with established improvement pedigrees to share their learning and expertise. Another priority is ensuring that trusts and local health and care systems have the resources, time and autonomy needed to develop capability-building programmes. Although building improvement capability has long-term benefits, the improvement journey can require significant upfront investment, so there is a strong case for national support to help more providers and systems get started. And given the very different starting points and requirements that different providers have, it is essential that this support is flexible.

Finally, the Appendix lists some key Health Foundation publications for further reading on the challenges of quality improvement and building improvement capability.

Part I: Why organisational improvement matters

What is an organisational approach to improvement?

An organisational approach to improvement is one that aims to embed a culture of continuous improvement and learning across an organisation, along with the means to make it a reality, with a view to delivering sustained improvements in the quality and experience of care. Specifically, it consists of an overarching improvement vision that is understood and supported at every level of the organisation. This vision is then realised through a coordinated and prioritised programme of interventions aimed at improving the quality, safety, efficiency, timeliness and person-centredness of the organisation’s care processes, pathways and systems.

Organisational approaches to improvement are underpinned by several key elements:

- Leadership and governance – visible and focused leadership at board level accompanied by effective governance and management processes that ensure all improvement activities are aligned with the organisation’s vision.

- Infrastructure and resources – a management system and infrastructure capable of providing teams with the data, equipment, resources and permission needed to plan and deliver sustained improvement.

- Skills and workforce – a programme to build the skills and capability of staff across the organisation to lead and facilitate improvement work, such as expertise in QI approaches and tools.

- Culture and environment – the presence of a supportive, collaborative and inclusive workplace culture and a learning climate in which teams have time and space for reflective thinking and feel psychologically safe to raise concerns and try out new ideas and approaches.

Although most sustained examples of organisational approaches to improvement demonstrate these features, there are also areas of variation. For example, many organisations in the NHS choose to create a central improvement team responsible for helping front-line teams design and implement microsystem improvements, as well as for overseeing large-scale change. However, other organisations have not done so and argue that creating a central team could lead to an over-reliance on a small group of experts to drive improvement.

In the field of innovation, a US study has highlighted the range of organisational designs providers have created to innovate and identify new services and processes, as well as meeting the demands of routine care management. These vary from dedicated innovation teams working independently from executive management and existing organisational processes, to ‘cross-functional’ teams that look at both incremental improvement and disruptive innovation, through to models built on the premise that innovation is everyone’s responsibility. A further area of variation is the type of improvement method used by organisations (for example, ‘lean’, ‘six sigma’, the ‘model of improvement’), although many believe that the method chosen is not as important as the level of rigour and consistency with which it is used, and whether there is commitment to it over time.

So, there is diversity as well as similarity between the various organisational approaches that exist, and successful approaches may look different in different organisations.

Why does organisational improvement matter?

Within the NHS, most improvement work is conceived and delivered at microsystem level. That is, it relates to care processes managed by small teams within specific departments and services. Although much of this work generates significant patient and service benefits, working solely at the microsystem level has limitations. In particular, discrete, time-limited local improvement efforts may not represent the most efficient use of staff time and resources, especially if they take place without any overarching mechanism to coordinate them or provide oversight., It can lead to the same problem being solved in multiple ways by multiple teams across the organisation, and sometimes on multiple occasions if organisational memories are short. A culture in which more professional kudos is often given to those who lead their own improvement projects, even very small-scale projects, than to those who participate in large-scale programmes, or seek to replicate proven interventions, is partly responsible for a profusion of small, one-off projects.

An integrated, organisation-wide approach to improvement, through which local activities are aligned, coordinated and appropriately resourced, can help to avoid this, and enable an organisation to derive maximum benefits from its improvement capability and the enthusiasm of its staff. It also provides the strategic constancy of purpose, momentum and infrastructure needed for complex, multifaceted improvement initiatives to emerge and become embedded. Without such a supportive context, many promising interventions have found it hard to gain traction and show a lasting impact.,

In addition, it is only at the organisational level that it becomes possible to oversee the creation of a positive, collaborative and inclusive workplace culture, which recent studies have shown is closely associated with improved patient outcomes. Another advantage of organisational-level programmes is that, in contrast to many national or regional training offers, they allow local, team-based skills development and give people the chance to learn by doing in their everyday practice.

The direction of travel within the NHS is towards greater integration of care, and partnership working between provider organisations. Regional partnerships such as Surrey Heartlands, which has set up its own academy aimed at supporting clinicians to work across organisational boundaries, will become more common in the years ahead. However, the strategies and activities of these partnerships will inevitably be underpinned and influenced by organisational-level programmes and activities in their regions. One of the first projects of the Surrey Heartlands academy, for example, is to develop a QI system that connects and aligns the work of organisations within the partnership. What is more, trusts with established improvement pedigrees, such as East London NHS Foundation Trust and Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (Box 1), see collaboration with neighbouring providers as a way to drive improvement within their communities and as pivotal to their organisational missions. Their improvement leadership and expertise, which has been shaped by their experience of delivering improvement across the multiple institutions and services within their trusts, is likely to be critical to the success of fledgling system-level partnerships. As such, the insights and learning from organisational-level improvement programmes will be relevant to the design and delivery of initiatives to build improvement capability across whole health and care systems.

What does 'good' look like?

Most of the NHS trusts in England that have been given an outstanding CQC rating have implemented an organisation-wide improvement programme of the kind described above – a trend the CQC itself picked out in its 2017 State of Care report. Moreover, the CQC has stated that it feels confident about the ‘long-term sustainability of the quality of care’ at those NHS trusts where it finds ‘an established quality improvement culture’ across the organisation., Organisations with a ‘mature quality improvement approach’, the CQC advises, have, among other things, prioritised improvement at board level, put in place a plan for building improvement skills at all levels of the organisation, and developed structures to oversee QI work and ensure it is aligned with the organisation’s strategic objectives.,

A case in point is East London NHS Foundation Trust. According to its most recent inspection report, the trust’s ‘well-established quality improvement programme’ was an important factor in it retaining its outstanding rating. The CQC found that ‘quality improvement remained central to the work of the trust’, with a growing number of staff receiving improvement training and getting the chance to use their skills to improve care. It also reported that the trust was using QI methods to support the delivery of some of its core strategic priorities, such as improving care pathways and access to services. East London is now looking to apply its improvement approach at a system level, by working with neighbouring organisations to improve local population health.

Similarly, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, rated as outstanding in 2016, has developed a capability-building programme that is being rolled out at all levels of the trust. As well as ensuring that there is a common way of working across the trust, and that an improvement ethos is shared by clinical and non-clinical staff, Northumbria is looking to build the capability needed to drive change across service and organisational boundaries. The trust aims to improve flow along care pathways by setting up a Flow Coaching Academy, bringing professionals from different services and sectors together with patients to plan and test changes on a collaborative basis.

Another trust rated as outstanding, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, has had a strategic focus on QI for over a decade. It has a mature, trust-wide capability-building programme, which includes a Microsystems Coaching Programme and a Clinical Quality Academy. Salford Royal’s approach to improvement includes an emphasis on identifying and tackling unwarranted variation in practice and measuring the effects of improvement efforts over time. To this end, Salford has sought to build the digital infrastructure and capability needed to enable staff to record, extract and analyse data in a timely and efficient way. Salford also became a Global Digital Exemplar in 2016 and is the first fully digitally enabled trust in England, with over 500,000 patient records across primary and secondary care.

The approaches taken by three outstanding trusts – East London, Northumbria and Western Sussex – are summarised in Box 1. There are many striking similarities in the methods they use to build improvement capability and deliver improvement, such as a commitment to creating an open and positive culture where staff feel empowered to lead change, and a willingness to invest in long-term change.

Other outstanding trusts have only recently adopted an organisational approach to improvement. For example, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, which was rated as outstanding in 2016, has taken steps since its inspection to expand QI capability and expertise within the trust. According to its 2018 Quality Strategy, the trust’s ‘focus on continuous quality improvement’ is designed to help it maintain its outstanding rating. An improvement collaborative has also been formed by staff who are members of the Q community, with a view to enhancing and promoting QI across the trust.

A major influence on the strategic direction of many of these trusts has been the work of leading provider organisations in North America and Europe. Examples include the Virginia Mason Institute Production System,, which has already worked with a number of English trusts, Intermountain Healthcare Delivery Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Thedacare Accountable Care and Jönköping County Council’s QI programme in Sweden. All these organisations have mature, organisation-wide improvement programmes that have delivered sustained improvements in quality over many years.

There is also much to learn from the improvement work of health and social care organisations in other parts of the UK. For example, South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust, an integrated provider in Northern Ireland, has a long-established, trust-wide, programme to build improvement capability that involves both health and social care staff. It offers useful learning for integrated care systems seeking to build improvement capability in a coordinated way in acute, community and social care settings.

Box 1: Summary of key QI strategies and programmes delivered by three English trusts rated as outstanding

East London NHS Foundation Trust

East London NHS Foundation Trust provides community health, mental health and specialist services to a population of 1.5 million people in East London, Bedfordshire and Luton. It operates from over 150 community and inpatient sites, employs almost 6,000 permanent staff and has an annual income of £400m. The trust’s QI programme began in 2014 and was given an outstanding rating by the CQC in September 2016, which it retained after its 2018 inspection. Key features of the trust’s approach to QI include:

- a strategic, long-term, board-level commitment to QI, board-level leadership of quality, and investment in partnership with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement

- a single, integrated system that incorporates quality planning, quality control, quality assurance and QI

- a central QI team to coordinate QI work and support teams, and a ‘people participation’ team

- a focus on the involvement of service users and carers as full partners in QI work

- the development of the ‘ELFT QI method’ to enable multidisciplinary teams, service users and carers to tackle quality issues that matter most to them

- clear, organisation-wide priority areas for improvement that bring together multiple teams across the organisation (eg enjoying work, violence reduction, improving access and reshaping community services), while also allowing teams to work on what matters to them and their service users

- a programme to build improvement capability that has trained over 3,500 people in 4 years at multiple levels of the organisation, from executives and board through to service users and carers

- a re-design of information systems to give staff better access to the data they need to understand quality and performance and to support their QI projects.

The trust has also recently decided to expand its mission to improve the quality of life of all the people it serves, with a new emphasis on population health. This approach, which focuses on the determinants of health as well as inequalities, will involve more partnership working and collaboration with neighbouring bodies in the local health system. The trust has already begun using QI to achieve the triple aim – of improving population health outcomes, experience/quality of care and value for money – for specific populations.

Key quotes from East London’s 2018 CQC inspection report

‘Quality improvement remained central to the work of the trust. The trust has made further progress in the use of a quality improvement methodology. The numbers of staff training and using the methodology had continued to grow. We saw that this methodology gave genuine opportunities for staff and patients in wards and teams to identify areas for improvement and make changes. The use of quality improvement was widespread throughout the trust.’

‘The trust had retained an overwhelmingly positive culture. Staff were largely very happy and said how much they enjoyed working for the trust. They valued the open culture and felt that when concerns were raised they were taken seriously and where possible addressed. They also felt supported by the trust’s ‘no blame culture’ and willingness to learn when things went wrong. This was reflected in the results of the staff survey where the trust overall staff engagement score was 3.90. It was better than the national average of 3.79 for trusts of a similar type. The trust recognised that not all teams were as positive as others, and was using the QI methodology to enable those teams to make changes where needed.’

Further information

- East London NHS Foundation Trust QI microsite (https://qi.elft.nhs.uk)

- East London NHS Foundation Trust Annual Report and Accounts 2017–2018

- East London NHS Foundation Trust Inspection Report 2018

Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust employs more than 10,000 staff and provides care from 11 main sites, as well as from community sites and in people’s homes across North Tyneside and Northumberland. These sites include an emergency care hospital, general and community hospitals, an outpatient and diagnostic centre, an elderly care unit and an integrated health and social care facility, as well as the management of six GP practices. It has an annual income of over £530m and was given an outstanding rating by the CQC in May 2016. The trust has:

- a named executive lead for QI, who is supported by clinicians and managers with formal QI training as well as ‘flow coaches’ and Q members

- a quality strategy that aims to balance compliance with national guidelines with prioritising local quality issues which are important to patients and staff. It also seeks to ensure that any plans align directly with the trust’s strategic vision, lead to measurable improvements in quality and encourage continuous improvement. Each year, it focuses on a small number of core quality priorities, which in 2018/19 are sepsis, frailty, patient flow, falls, and patient and staff experience. The trust has one of the most comprehensive patient and staff experience programmes in the NHS, using real-time data to enable improvements in quality

- set up a 'quality lab': a forum attended by a wide range of executive representatives, senior clinicians, transformation managers and service leads to monitor its QI programme and address improvement barriers within the organisation. They have developed the trust’s ‘formula for improvement’, which incorporates five steps:

- engage and involve

- fully understand the current situation

- generate ideas

- start small – make a change and look at the impact

- share, sustain and celebrate

- developed a ‘leading for improvement’ training programme, run over 3 days, that incorporates the trust’s formula for improvement. This is being rolled out across the organisation for all levels of staff, clinical and non-clinical. ‘Pocket QI’ 1-day training is also available to participants in apprenticeship and development programmes

- set up a Flow Coaching Academy to provide training for improving flow at care pathway level. Eleven care-pathway teams have been coached to date, including frailty, emergency department and 'discharge to assess'

- established RUBIS.Qi, the external-facing QI delivery arm of the trust. RUBIS.Qi is the official support provider for the latest rounds of the Health Foundation’s Scaling Up and Innovating for Improvement programmes, coaching more than 40 teams across the NHS. In partnership with the King’s Fund, it is also delivering NHS Improvement’s Leadership for Improvement board development programme, which is supporting 20 boards to embed QI in their organisations.

Key quotes from Northumbria’s 2016 CQC inspection report

‘When we spoke with managers and staff throughout the trust, the “Northumbria Way”, which incorporates the trust’s values, behaviours and culture was evident[…] There was a "can do" culture that is evident across the organisation with staff encouraged at all levels to make changes to services that would improve the quality of care to patients.’

Further information

- Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Operational Plan 2018/19

- Quality Account 2017/18

- Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Quality Report

Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust operates three hospitals and a range of community services, including GP surgeries. It employs 7,000 staff and has an annual income of £435m. It was given an outstanding rating by the CQC in December 2015. In 2016, the trust’s chairman, chief executive and executive directors also took on the leadership of neighbouring Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals Trust, whose CQC rating has since risen from inadequate to good. The trust has:

- implemented a trust-wide transformation programme, Patient First, to make continuous improvement part of staff’s day-to-day role and to empower and enable them to drive change. It is based on the lean approach used successfully by providers such as Thedacare in the US

- established a ‘Kaizen Office’ with a dedicated team to establish a consistent, sustainable, trust-wide approach to improvement over the long term

- used a patient-first concept to align its QI approach with its workforce strategy and its efforts to ensure that the trust is financially sustainable

- developed a capability-building programme to equip staff with the skills to deliver continuous improvement, with training available for every staff member, beginning at induction and going all the way through to ‘lean practitioner’ level

- asked managers to empower their teams to identify and make improvements in their areas of work and introduced improvement huddles to give all staff a voice in identifying opportunities for change.

Key quote from Western Sussex’s 2016 CQC inspection report

‘The executive team provided an exemplar of good team working and leadership. They had a real grasp of how their hospital was performing and knew their strengths and areas for improvement. They were able to motivate and enthuse staff to ‘buy in’ to their vision and strategy for service development. Middle managers adopted the senior manager’s example in creating a culture of respect and enthusiasm for continuous improvement. Innovation was encouraged and supported. We saw examples that, when raised directly with the Chief Executive and her team, had been allowed to flourish and spread across the services. We saw respectful and warm relationships internally amongst staff teams, the wider hospital team and outwards to external stakeholders and the local community.’

Further information

* According to Professor Ted Baker, the Chief Inspector of Hospitals, ‘QI has been shown to deliver better patient outcomes, and improved operational, organisational and financial performance when led effectively, embedded through an organisation and supported by systems and training. When QI is used well, it gives us confidence about the long-term sustainability of the quality of care. More informally, when we visit trusts that have an established QI culture, they feel different. Staff are engaged, they are focused on the quality of patient care, and they are confident in their ability to improve. This is also reflected in surveys of staff and patient satisfaction.’

† The CQC draws a distinction between efforts focused on ‘improving quality’, which it argues all NHS trusts will be undertaking (eg through their quality assurance and control processes) and ‘quality improvement’, which involves ‘the use of a systematic method to involve those closest to the quality issue in discovering solutions to a complex problem’.

‡ An approach pioneered by Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and supported by the Health Foundation.

§ Q is a Health Foundation initiative that connects people with improvement expertise across the UK. The community includes people at the front line of health and social care, patient leaders, managers, researchers, commissioners, policymakers and others.

¶ ‘Kaizen’ is a core concept of the Toyota Production System, which, loosely translated from the Japanese, means continuous improvement. It aims to ensure maximum quality, the elimination of waste, and improvements in efficiency.

Part II: Building an organisational approach to improvement

The improvement journey

Building the capability, infrastructure and culture needed to deliver sustained organisation-wide improvement is a journey that can take several years.

In most cases, there is no single driver for the development of an organisational improvement programme. It can be the result of many different factors: a major patient safety incident that reveals systemic failings and highlights an urgent need to do things differently; the arrival of a group of senior leaders or clinicians with a shared interest in improvement; or the realisation, from a peer learning visit to an influential provider elsewhere, that the organisation is not performing as well as it imagined. Evidence of unwarranted variations in patient outcomes, staff experience and use of resources both within the trust and when compared with other trusts can also help to galvanise change. External drivers, such as a critical inspection, can also have a major effect.

There are six steps an organisation should take to plan, deliver and sustain an organisational improvement programme.

1. Assessing readiness

While organisation-wide approaches to improvement vary in their gestation and development, a useful starting point for organisations is to understand their ‘readiness for change’., This is the extent to which the organisation is both psychologically prepared for change (shown by the maturity of its learning climate), and has the right infrastructure, governance arrangements and leadership in place. There are numerous tools available to guide organisations through this process such as the ORCA tool, the ORIC measure, Chamberlain’s QI building blocks framework, AQuA’s QI maturity matrix and the Health Foundation’s own high-level organisational-improvement checklist. Few organisations will be able to meet all the key change criteria at the start of their improvement journey, but they need to be clear about where their capability gaps are, and have a good plan to address them.

2. Securing board support

In most organisations, an essential early step is securing the support and confidence of the board. Without their commitment to a long-term programme of improvement, and their willingness to finance the skills and infrastructure development needed to implement it, little can be achieved. A strong clinical voice at board level can often be useful in persuading the board to make QI a priority.,

Much depends on the board’s level of confidence and authority. A stable board with an established identity, and which is highly regarded externally, is well placed to embrace the challenges associated with a long-term, whole-organisation improvement programme. Moreover, it has the confidence to filter the offers of support and recommendations that come from national and regional bodies appropriately, giving priority to those that fit their improvement vision or way of working. By contrast, a newly appointed chair or chief executive in a trust with a history of performance challenges that is under heavy regulatory, political and media scrutiny, may not have the confidence or capital to embark on an ambitious programme of long-term improvement.,

3. Securing wider organisational buy-in and creating a vision

Having secured board-level support, the challenge is to persuade others across the organisation of the case for improvement and create a compelling improvement vision. To do this, improvement leaders need to understand and tap into the intrinsic professional motivations of staff at each level of the organisation, and ensure that any initiative does not become caricatured as a top-down programme, or driven by cost-cutting. One way to guard against this is by building in stages, perhaps by working first with a few improvement enthusiasts, and then convincing others to follow their lead once they have demonstrated a positive impact on care quality and staff experience.

Embedding a culture of distributed leadership across the organisation, with the aim of giving staff at all levels the opportunity, permission, and the confidence to identify and test new ideas, is key. Time spent by trust leaders trying to unlock the expertise that lies in every part of the trust, and encouraging and supporting staff to use this knowledge to help drive improvement, can be invaluable. As well as chipping away at the perception that there isn’t time to improve, a concerted push by senior leaders to champion improvement that is driven and owned by teams on the front line will help to address the anxiety that some staff may feel about taking on the responsibility for doing things differently. In what is still a very hierarchical service, in which seniority matters and some professions are perceived as more likely to provide leadership than others, these barriers should not be underestimated.

As well as working to ensure that there is broad clinical support for improvement, senior leaders need to invest time in bringing junior and middle managers and other corporate staff on board. Having engaged and supportive ward managers, for example, who want to be involved in improvement and will tackle the obstacles that will inevitably emerge is essential. What’s more, it is vital there is no dissonance between the senior leaders’ message about fostering and embedding distributed leadership and the language and behaviours of managers throughout the organisation.

4. Developing improvement skills and infrastructure

At the same time, organisations need to begin to build their improvement infrastructure. A key consideration is how to ensure teams at each level of the organisation have the general and specialist improvement skills needed. To deliver sustained, organisation-wide improvement, a systematic approach to building improvement capability across the trust is required. Many capability-building frameworks and instruments have been developed to support this process. Some of these focus on the type of skills and behaviours required and some consider the ‘dose’ of skills needed at each level of an organisation., This investment in improvement skills needs to be accompanied by the development of measurement systems able to collect, analyse and feed back data on the effects of improvement activity, and the capability and capacity to make full use of these systems. The development of standard operating models to ensure the standardisation of core processes and activities across the trust, and, where appropriate, with other providers in the local system, should also be considered. Alongside national initiatives such as Getting It Right First Time and NHS RightCare, such standard operating models can help trusts to address unwarranted variation in service delivery.

5. Aligning and coordinating activity

As the improvement programme grows and matures, the task of aligning the different strands of improvement activity becomes ever more important and challenging. This coordinating role, which would normally be undertaken by senior figures with oversight of all trust activity, is necessary to ensure that individual initiatives are consistent with the trust’s overall strategy and mission, and that improvement teams and other organisational development activities are not pulling in different directions. It is also crucial in identifying and unlocking operational barriers to improvement and ensuring that resources are allocated intelligently.

6. Sustaining an organisation-wide approach

It can take time for an improvement programme to become really embedded in an organisation. Maintaining momentum over that time, and ensuring that staff, patients and external stakeholders remain engaged and supportive of the programme, arguably requires as much effort and skill as it takes to get it underway. Having generated some early wins by focusing on the services most amenable to improvement, or those where there is the greatest appetite or capability for change, the challenge is then to maintain that success, while also engaging services and teams that are less ready for improvement. The reality is that the pace of improvement is uneven, and performance can sometimes fluctuate as new ideas are tried, adapted and improved.

All this can be challenging, both for the QI leaders within an organisation and for the board, which may have invested significant political capital and money in the programme. Yet board-level support for the programme at this point is critical. The long-term success of the programme can hinge on the board’s willingness and ability to manage the delivery expectations of external stakeholders, to give front-line teams the ‘air cover’ they need to experiment and refine their interventions, and to maintain a constancy of purpose in the face of external pressures.,

What helps is a growing awareness that developing a successful organisational improvement programme is a long journey. The well-publicised improvement journeys of leading US providers such as Intermountain and Virginia Mason, which began several decades ago, coupled with more local examples, such as Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, are useful in dispelling the notion that an organisation-wide approach to improvement can somehow be created overnight.

Different approaches to building improvement capability and expertise

Most trusts that have developed an organisational approach to improvement have, at some point, looked for external support. The extent of the support varies. Some have sought informal advice and assistance from peers at the start of their improvement journey, but have focused on building improvement capability from within by strengthening the improvement coaching and leadership skills of their existing staff. Others have entered into more formal partnerships with external organisations in the commercial or not-for-profit sectors, or with other organisations within the NHS.

Building from within

Some trusts have focused primarily on building the improvement capability of existing staff through in-house programmes. The impetus and initial leadership of such programmes often comes from staff who have attended external training programmes and fellowships and have used this expertise to develop the first wave of improvement coaches and mentors within the trust.

For example, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust has developed a Microsystems Coaching Academy, training 273 improvement coaches to help teams improve care. Building on this approach, the Health Foundation is now partnering with Sheffield to develop a network of Flow Coaching Academies. As of 2019, there are seven local Flow Coaching Academies across the UK, each helping clinicians and managers develop capability in applying team-coaching skills and improvement science at care-pathway level.

Support from commercial and not-for-profit organisations

NHS trusts can turn to commercial and not-for-profit organisations for strategic advice and practical support in developing their improvement capability. For example, the US-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement offers a range of ‘customised services’, from an on-site diagnostics service aimed at identifying ‘high-value improvements’, through to support for large-scale improvement initiatives and ‘multi-year, multi-touch’ strategic partnerships such as its arrangement with East London NHS Foundation Trust. Providers can also access support from established commercial consultancies or NHS bodies such as NHS Interim Management and Support.

At a regional level, Academic Health Science Networks play a role in creating the right environment for change within and between organisations, by identifying and spreading innovations, creating opportunities for organisations to connect and share ideas, and leading regional-level change programmes. Meanwhile, regional improvement academies and centres, such as the Yorkshire and Humber Academy, West of England Academy, Cumbria Learning and Improvement Collaborative, and Advancing Quality Alliance, are sources of improvement skills training, along with learning events and bespoke consultancy support. This allows smaller providers with limited in-house training capacity to contract out some of their needs related to building improvement capability. These organisations also publish resources for providers on how to build and deploy improvement capability: the Advancing Quality Alliance’s recent paper on building a culture and system for continuous improvement is a good example.

Support from peer organisations

NHS trusts aiming to improve the quality of their services have often looked for inspiration, advice and support from exemplar organisations in the UK and beyond. Historically, this learning has tended to take place through informal peer-to-peer engagement, learning visits or secondments. However, the publication in 2014 of the NHS’s Five year forward view and the Dalton review, which recommended that ‘ambitious organisations with a proven track record should be encouraged to expand their reach and have greater impact’, has prompted a number of trusts to expand and formalise their offer to their peers. For example, Northumbria Healthcare offers a range of clinical and corporate services and consultancy support through the Northumbria Foundation Group, one of the Acute Care Collaboration vanguards within the New Care Models programme. With The NHS long term plan calling for a greater emphasis on ‘mutual aid’ and collaboration between providers within local health systems, both informal and formal peer-support activity looks set to increase.

Another emerging trend is for trusts to enter into a formal partnership, either on a mandatory or voluntary basis. Such partnerships can help improve performance and tackle unwarranted variation in service delivery between trusts by giving participants the opportunity to learn from the best-performing trusts and to standardise practice. In 2016, for example, Salford Royal, one of the first trusts in the country to receive an outstanding CQC rating, agreed to provide leadership and improvement support at the neighbouring Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust. The partnership, which led to Salford’s chair and chief executive taking on the equivalent responsibilities at Pennine Acute Hospitals, followed a CQC inspection that gave Pennine Acute Hospitals an inadequate rating. In 2017, the partnership was cemented through the creation of the Northern Care Alliance, consisting of four locality-based ‘care organisations’. Meanwhile, Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, which has an outstanding CQC rating, took on the leadership of neighbouring Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust in 2017. In 2019, Brighton’s rating rose from inadequate to good.

Investment

The resources required

Finding the resources to get an organisation-wide programme up and running can be a significant challenge. It is possible to build capability and support improvement teams using existing staff and resources, but that will require organisations to release staff from their normal duties to teach or plan improvement. Without spare resources to back-fill posts and set up support processes, among other things, this can prove very difficult. The reality is that significant upfront investment is usually necessary. For example, Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, a community and mental health care provider with a turnover of £245m in 2016/17, has invested £1.4m over 2 years in bringing in an external partner to support its bid to develop QI capability across the whole of the trust. It has also a recruited a central ‘QI office’ of six staff, launched a quality management and improvement system to train and support staff and developed a ‘true north’ improvement vision.

Even after this initial investment, there will still be annual running costs of an improvement programme once it is underway (eg to finance a central improvement team). Estimates of how much money is needed are hard to find. One estimate from the US suggests that providers allocate up to 1% of their annual turnover to their improvement programmes and infrastructure. It is uncertain, however, how applicable this figure is to a UK context, given that this agenda is considerably more developed in the USA than here. Trusts would benefit from new guidance on this topic to help them plan their programmes.

The return on investment

Quantifying the return on QI investment is notoriously difficult. Health care provider organisations are complex entities, and it can be hard to disentangle the effects of specific QI interventions from those of other activities. The task is harder still when it comes to organisation-wide improvement programmes composed of a diverse range of workforce and infrastructure-related investments. Evidence about return on QI investment tends to come from case examples, such as a 2013 study of the Mayo Clinic in the USA.

One organisation that has tried to identify and understand the return on investment from its trust-wide improvement programme is East London NHS Foundation Trust (Box 2).The trust has developed a framework for evaluating its return on investment, comprising six domains. The framework distinguishes between the benefits of specific improvement initiatives, which are more amenable to economic analysis, and the wider cultural benefits of organisational improvement (eg improved staff experience and retention and fewer absences), which are harder to quantify or attribute to the programme, but are still significant. East London argues that it is only by looking at its return on investment through these multiple lenses that the true value of its trust-wide programme becomes visible.

Box 2: The East London NHS Foundation Trust framework for evaluating return on investment from QI

- Patient outcomes and experience – improving practices, pathways and services to improve treatment and care.

- Staff experience – improving staff engagement has an impact on recruitment and retention.

- Productivity and efficiency – removing non-value-adding steps in processes results in improvements in productivity and efficiency.

- Cost avoidance – improving services and the work environment may allow an organisation to avoid significant costs, such as reductions in staff sickness (decreasing use of agency staff).

- Cost reduction – improving services may also create opportunities for removing costs entirely from the system, such as reducing the number of beds and wards needed by improving length of stay.

- Revenue generation – building a reputation for quality and improvement can help to generate new business and reduce the risk of being decommissioned or losing business.

At a time when many trusts are struggling to find and keep staff, and are investing significant resources in recruiting and training new staff, or in covering vacant posts through agency staff, the potential workforce benefits of investing in improvement, highlighted by East London’s framework, are significant. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that a positive organisational culture is associated with improved patient safety and quality outcomes.,

Nevertheless, it can take some time before it is possible to start generating a return on investment. Furthermore, the experience of the Jönköping QI programme in Sweden suggests there is an ‘investment threshold’ that must be crossed before organisation-wide performance improvements start to be realised.

What are the enablers of organisational improvement?

Translating a desire for change into an organisation-wide programme capable of delivering sustained improvements in safety, quality and experience presents a set of challenges. Through analysis of the peer-reviewed improvement literature and Health Foundation improvement programmes and publications, we have identified enabling factors that contribute to the success of an organisational approach to improvement. They fall into four broad categories:

- leadership and governance

- infrastructure and resources

- skills and workforce

- culture and environment.

Leadership and governance

For any organisation-wide programme to flourish, there needs to be visible, focused leadership for improvement at board level, right from the start., A clear endorsement of the programme signals that it is central to the trust’s strategy for the long term, and can be vital for getting the support and momentum the programme needs. However, the board also needs to show its sensitivity to previous improvement efforts across the trust and highlight the importance of building on that work and the improvement expertise of existing staff.,,, This will help to engage staff who may be experiencing a degree of ‘improvement burnout’ and may be sceptical of new improvement visions. A willingness by the board to seek out staff and patient views and use them to shape the improvement vision will also help it resonate across the organisation.,

The board also has to maintain constancy of purpose, understanding that changing complex systems is difficult, unpredictable and time consuming. Improvement teams need time and space to plan, prototype, evaluate and refine interventions.,, It can help if there is stability at board level, in terms of both its membership and its culture.

Good strategic and political skills are important. The ability to reconcile the tension between short-term performance demands and long-term strategic improvement objectives (‘organisational ambidexterity’) allows the board to give improvement teams at the front line the ‘air cover’ they need to deliver change.,,,, Also valuable is a strong internal locus of control and the ability to prioritise the external demands and offers that complement the organisation’s goals.,

The improvement culture of the organisation is influenced by the behaviours and attitudes of the board. A governance climate geared towards ‘problem sensing’ rather than ‘comfort seeking’, is important in shaping a reflective, learning culture within the organisation. Looking outwards to identify and embrace knowledge, expertise and ideas developed in other organisations is also important.

Embedding a culture of distributed leadership at each level of the organisation is essential for teams at the front line to feel they have the autonomy and permission to lead improvement.,,, In addition, patients and service users should be encouraged to co-create and contribute to improvement work, as well as to inform organisational improvement strategy.,,

Boards and senior leaders need effective governance and management processes so that they can ensure that all improvement activities are aligned with the organisation’s strategy and that they fit with existing workflows and systems.,,,,,,, For leaders to effectively monitor and evaluate the delivery of improvement interventions, they need access to reliable, timely and relevant data about organisational performance, as well as the skills to analyse and act on them appropriately.,,,

Infrastructure and resources

A management system and infrastructure capable of generating timely, relevant and accessible data on the delivery of key improvement indicators is an essential feature of any organisation-wide improvement programme.,,, As well as the means to build and maintain such an infrastructure, improvement teams need the skills to collect and interpret relevant information and to ‘measure for improvement’,,,,, along with access to skilled analysts.

Delivering and sustaining improvement can require significant resource. In addition to securing sufficient money, time and physical space to drive improvement, organisations need effective mechanisms for deciding between competing requests for resources.,,, They also need to consider how to encourage and reward improvement across the organisation.,,,

Skills and workforce

To ensure that an organisation has the necessary capability to drive improvement, all staff should have at least a basic grasp of improvement approaches and tools,, and be given the opportunity and guidance to put their skills into practice., Efforts to promote awareness of the ‘habits of improvers’ and steps to strengthen them across the organisation are also necessary. For clinical teams and communities, this needs to be combined with ongoing training about methods to standardise and improve care.,,

Meanwhile, operational managers and clinical improvement leaders should have the skills and motivation to implement microsystem-level improvement., There also needs to be sufficient capability and capacity to analyse data to continually monitor quality and performance.

As well as having staff with the right skills, organisations need effective social and professional networks in place for improvement interventions to get embedded as widely as possible.,, The presence of a stable and cohesive ‘social architecture’ – how people cluster, connect and coordinate to deliver a coherent and integrated service – is another core enabler of organisation-wide change.,

Finally, it is also important to ensure that every part of the organisation – clinical and corporate – can plan and deliver improvement. Aligning workforce-related strategies (recruitment, retention, pay and benefits, education and training) and functions (HR, payroll, occupational therapy) with improvement strategies can create opportunities for productive joint working between corporate and clinical staff.

Culture and environment

The presence of a supportive, collaborative and inclusive workplace culture has a significant bearing on an organisation’s ability to deliver improvement. A positive organisational culture has been consistently associated with a range of improved patient safety and quality outcomes.

Organisations also need to focus on developing a learning climate in which:

- leaders express their own fallibility and the need for team members' input

- individuals feel that they are essential, valued, respected and knowledgeable partners in the change process,

- individuals feel psychologically safe to question existing practice, report errors and try new methods,,

- teamwork and multidisciplinary collaboration is promoted and supported,,,,

- there is sufficient time, space and opportunity for reflective thinking, learning and evaluation.,,

These factors help maximise an organisation's absorptive capacity for learning, problem solving and adopting new ideas and innovations. Box 3 summarises the skills and behaviours that staff at each level of an organisation need to design, implement and embed an organisation-wide approach to improvement.

Box 3: The skills and behaviours needed at each organisational level

Boards and executive teams need to:

- provide visible and focused leadership for improvement

- drive the development of a compelling mission, purpose and way of working

- reconcile short-term external demands with long-term organisational improvement objectives

- show constancy of purpose and give front-line teams time, space and permission to plan, develop and refine improvement interventions

- make available sufficient resources to identify, plan and deliver improvement

- promote a culture of distributed leadership throughout the organisation

- have access to reliable, timely and relevant data about organisational performance and the ability to analyse the data and act appropriately

- ensure that the views of staff and patients help shape organisational strategy and improvement priorities

- build on previous improvement work and ensure that existing improvement expertise in the organisation is valued and maximised

- seek out relevant knowledge, expertise and innovation from outside bodies and use it to inform improvement strategy and practice

- create a governance climate geared to ‘problem sensing’ within the organisation, rather than ‘comfort seeking’

- ensure alignment between improvement activities, workforce functions and organisational strategy.

Operational managers and clinical improvement leaders need to:

- have the skills and motivation to implement microsystem-level improvement.

Staff at all levels need to:

- be empowered to identify and implement improvement

- have a basic grasp of improvement approaches and have developed the ‘habits of improvers’.

Patients, service users, families and carers need:

- the opportunity and support to co-create improvement and inform organisational improvement strategy.

Everyone needs to be supported with:

- measurement, monitoring and feedback mechanisms capable of the timely collection and analysis of multiple types of data

- a cohesive, supportive, collaborative and inclusive workplace culture

- a learning climate that promotes teamwork and multidisciplinary collaboration and in which people feel psychologically safe to question existing practice and try out new ideas and approaches

- sufficient resources and time to identify, plan and deliver improvement.

What are the barriers to organisational improvement?

The challenges involved in implementing and sustaining an organisation-wide improvement programme are many and varied. Organisations that have succeeded in overcoming them are the exception rather than the rule.

Almost all NHS trusts in England have some experience of using QI methods, but usually at the level of individual improvement initiatives. For example, a study looking at the implementation of lean-based improvement approaches in English NHS trusts found that in 2010, 78% of trusts had some experience of lean, but very few had implemented a coherent, managed programme of lean-based activity. Even fewer had put in place a lean-inspired system of working that ‘was championed at an executive level as a whole-hospital approach’. (The Bolton Improving Care System and the North East Transformation System were among the small handful of those identified who had done so.) A US study of hospital-based improvement programmes produced similar results: of the 1,200 hospitals surveyed, 69% had adopted a systematic improvement approach such as lean or six sigma, but only 12% had reached a ‘mature, hospital-wide stage of implementation’.

The size and complexity of NHS trusts is one challenge. Most NHS trusts are complex, multi-site systems providing a wide range of care services to large and often dispersed populations (often as a result of successive mergers over several decades). For example, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust – which employs 10,000 staff, provides care from 11 sites across the county and manages six GP practices – is a major integrated care system. Even many smaller trusts, such as those based around traditional district general hospitals in small towns and suburban areas, now typically incorporate a number of acute and community-based facilities.

Current workforce and financial pressures are also significant challenges.,, At a time when trusts are dealing with rising demand for care at the same time as resource constraints and staffing shortages, the challenge of planning and delivering a programme of trust-wide improvement can seem overwhelming. Given that the full benefits of such investment may only be realised several years later, it is understandable why some trusts focus on meeting nationally defined access and financial targets. Furthermore, trusts that are under severe pressure, and trapped in cycles of crisis followed by short-term fixes, are often also psychologically ill-prepared for systemic, long-term change. Facing a series of existential threats, they might adopt a highly bureaucratised form of management that leads to defensive, reactive behaviour and superficial displays of compliance rather than genuine efforts at improvement.

The Health Foundation’s 2015 evidence scan on the barriers to improvement in the NHS provides a useful overview of the main organisation-level obstacles to change (Box 4). Some reflect the absence of the enablers described above, or dynamics antagonistic to them. Others are independent factors that can also be detrimental to organisational improvement.

Box 4: Key organisational barriers to improvement

(From What's getting in the way? Barriers to improvement)

Culture

- Lack of culture of improvement

- Perceived culture of blame

- Lack of priority placed on improvement

- Risk-averse culture and prioritisation of defensive practices

- Behaviours and ‘rituals’ that undermine improvement

Leadership

- Lack of strong leadership and a shared vision for improvement, including at board level

- Hierarchical leadership structure rather than transformational or engaging leadership

- Not ensuring leadership and autonomy for improvement at multiple organisational levels

- Lack of accountability for improvement

Focus

- Limited focus on person-centred care

- Attempting to localise everything, rather than drawing on regional or national expertise

Resources

- Lack of management time or organisational capability

- Staff shortages and high use of agency staff

- Lack of dedicated funding

- Systems not set up to support integration of improvement into existing processes

Information

- Lack of information sharing within organisations and teams

- Insufficient use of the data available

- Insufficient information and analysis systems

- Lack of, or inflexible, feedback structures in place

Timing

- Wanting to see ‘quick wins’ rather than allowing improvement time to embed

- Not allowing dedicated staff time for training or implementation

Engagement

- Insufficient engagement of professionals and patients

A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring the characteristics of struggling health care organisations identified similar issues. Low-performing organisations often had a poor organisational culture and dysfunctional external relations and lacked a cohesive mission and adequate infrastructure. In some cases, their difficulties were aggravated by a ‘system shock’, such as a change in leadership, organisational restructuring, or the implementation of a major IT system.

** See https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk and www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare for more information.

†† Consultancy.uk provides details of consultancy firms operating in the UK in healthcare (www.consultancy.uk/news/17157/the-best-consulting-firms-for-healthcare-pharma-and-life-sciences).

‡‡ From a presentation by T Ferris at the Health Foundation Annual Conference, 2017.

Part III: Support for organisations on the improvement journey

National support for organisations in England

Despite the policy focus on externally driven change in recent decades (via mechanisms such as regulation, targets and financial incentives), there have been consistent efforts to facilitate organisational improvement since the publication of The NHS Plan in 2001. Each successive national improvement agency has encouraged organisations to develop coordinated improvement programmes that encompass every service they provide, along with the necessary supporting infrastructure. Many national improvement programmes have been created since 2001 in support of this aim. An example is the Leading Improvement in Patient Safety programme (2009–2013), which was described by the NHS Institute as a ‘comprehensive programme designed to help NHS trusts build the capacity and capability to eliminate harm’. Participation in these programmes has been an important staging post in the improvement journey of many trusts with established improvement pedigrees.

Over the years, however, messages from national bodies on how to deliver improvement, and what to prioritise, have not always been aligned or consistent. In 2016, in an effort to address this challenge, the National Improvement and Leadership Development Board, which brings together the 13 key health and social care arm’s-length bodies and provider membership bodies in England, published a national framework (Developing People, Improving Care) to guide action on developing improvement skills and leadership development in the NHS. Designed to ensure that the national bodies responsible for driving, supporting and regulating quality are able ‘to engage across the service with one voice’, it sets out the cultural conditions for change and stresses the need for collective action to deliver them.

Much of the activity at national level focused on building the capability for improvement within organisations is currently led by NHS Improvement. One of its core objectives is for every provider organisation to ‘implement effectively a recognised continuous improvement approach’ by 2020. To help achieve this, NHS Improvement has implemented a series of national training and support programmes (Box 5), and developed improvement resources. For example, in 2017 it published a guide that describes how providers can identify the type and level (or ‘dose’) of improvement skills they need to develop at each level of the organisation. This work at NHS Improvement is similar to an exercise led by NHS Scotland in 2013–2015, which aimed to assess the state of QI infrastructure in Scotland by mapping improvement activity and identifying strengths and gaps.

Moves to bring about NHS England and NHS Improvement together as a single organisation are likely to have important implications for the improvement activities of local providers and systems. A new Director of Improvement post has been created as part of this restructuring. As well as enabling the integration and alignment of national programmes and activities, this should help to set consistent expectations for providers and local health systems. As part of this agenda, NHS England and NHS Improvement will need to consider the right balance between directly providing improvement programmes and support themselves, and commissioning them from external bodies while supporting trusts and systems to take such opportunities up.

The CQC, which monitors health care providers, has identified the promotion of innovation and improvement as a key strategic goal. It has issued guidance to CQC inspection teams stating that they ‘should always assess the presence and maturity of a QI approach within a provider organisation’ and has worked with NHS Improvement to develop a joint ‘well-led framework’ to inform inspections and trusts’ internal development reviews. The framework aims to increase the emphasis that trusts place on developing organisational culture, improvement and system working. Furthermore, the CQC also seeks to capture and share learning from trusts that have met the ‘well-led’ criteria.

Box 5: Some national support and training programmes involving NHS Improvement

Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT)

This programme is designed to improve medical care within the NHS by reducing unwarranted variations. GIRFT identifies changes that will help improve care and efficiency, such as the reduction of unnecessary procedures. Having begun as a pilot within orthopaedic surgery, the GIRFT methodology is now being rolled out across 35 surgical and medical specialties.

NHS partnership with Virginia Mason Institute

This programme is a 5-year partnership between the Virginia Mason Institute and five NHS trusts to support them to develop a ‘lean’ culture of continuous improvement. It began in 2015 and is now being evaluated by Warwick Business School (with Health Foundation support).

Lean programme

This 3-year programme, open to all types of provider organisation, was launched in early 2018. It aims to support seven providers to deliver a lean management system which recognises the context and needs of their organisation.

Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign programmes

Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign (QSIR) programmes are aimed at clinical and non-clinical staff involved in service improvement within their organisation or wider system. They train participants in the use of tested improvement tools and approaches, such as process mapping and measurement for improvement, and encourage reflective learning. Options include a 1-day improvement fundamentals course; a 6-month improvement practitioner course; and the QSIR college, which is a train-the-trainer course.

Leadership for Improvement board development programme

The programme focuses on teaching boards what it takes to lead improvement in organisations. The first cohort of the programme will run from January 2019 to March 2020.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has produced resources to support improvement, for example its QI resource for adult social care aimed at commissioners and provider organisations.

How can we make further progress?

Ultimately, providers and systems themselves are responsible for delivering this agenda. Unless trusts have the appetite to plan and deliver organisation-wide improvement programmes, and to give them the priority they need to succeed, and unless leaders see it as a core element of good organisational management, little will be achieved. Policymakers and system leaders should expect trusts to engage in QI and build their capability for improvement. The inclusion of this area in CQC inspection guidance and their well-led framework is therefore a positive development. However, as this report makes clear, policymakers and system leaders also have a responsibility to support this agenda.

First, national bodies with regulatory, performance-management or support responsibilities must speak with one voice about organisational improvement and develop a shared model of change., The Developing People, Improving Care framework is an attempt to realise this ambition. This approach should be sustained over time, and the commitment expressed in the framework matched with action. For instance, wider, national change programmes must complement this work, rather than creating conflicting initiatives that make it harder to provide the local leadership required for sustained organisational improvement. An awareness of the time needed for a mature, organisation-wide improvement programme to become embedded will be crucial, as will a commitment to supporting NHS trusts and systems as they make this long-term journey.

Second, the NHS needs to do more to encourage and support organisations with established improvement programmes to share their learning and expertise. The improvement stories of trusts like East London NHS Foundation Trust show how important visits to pioneering trusts such as Salford Royal and Tees, Esk and Wear were in motivating board members about QI. However, the outreach offers of most leading NHS providers are not as well developed as those of US providers, such as Virginia Mason. Strengthening and expanding the outreach programmes and formal consultancy offers of high-performing trusts would therefore be valuable. Encouraging and enabling trusts with proven improvement track records to build relationships with and support their peers has the potential to deliver greater long-term value to the NHS than the short-term use of commercial management consultancies.

And finally, trusts will need the resources, time and autonomy to develop capability-building programmes. Despite the medium- and long-term benefits of building improvement capability, the improvement journey can require significant upfront investment. At a time when organisations are under significant financial pressure, this investment can be a barrier for many trusts and local systems. There is therefore a strong case for national support to help more providers and systems get started. And given the very different starting points and requirements that different providers have, it is essential that this support is flexible. A critical part of this is supporting providers in assessing their current needs and readiness for change. Evaluation is another key part of the picture, to help organisations and systems understand the impact of their capability building and to help the NHS better understand the most effective strategies.

The NHS long term plan makes a welcome commitment to ‘supporting service improvement and transformation across systems and within providers’ by ensuring that they have ‘the capability to implement change effectively’. It includes an initiative, in partnership with the Health Foundation, to increase the number of integrated care systems that are building improvement capability. The Health Foundation will work with NHS leaders to design and take forward this programme of work. Also important is The NHS long term plan’s announcement of a ‘duty to collaborate’ between providers and commissioners, which sees ‘thriving, successful organisations’ helping their neighbours develop their own capability. This duty will also underpin system-level efforts to build improvement capability, which will be vital to achieving The NHS long term plan’s ambition of creating integrated care systems across the country.

§§ NHS Modernisation Agency (2001–2006), NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2006–2013), NHS Improving Quality (2013–2016), and now NHS Improvement.

Appendix: Key Health Foundation publications

Constructive comfort: Accelerating change in the NHS (2015)

This report identified the seven success factors for change at any level of the health system, but particularly locally in organisations. It looks at the reasons why they are not consistently present in the NHS, and considers what needs to be done to embed them more widely.

The habits of an improver (2015)

This report offers a way of viewing the field of improvement from the perspective of the men and women who deliver and co-produce care on the ground – the improvers on whom the NHS depends. It describes 15 habits that such individuals regularly deploy.

Building the foundations for improvement (2015)

This learning report looks at how five trusts from across the UK built improvement capability at scale across their organisations.

Perspectives on context (2014)

This was a series of essays by leading academics exploring the issue of context in improving the quality of patient care.

Context for successful quality improvement (2015)

Building on Perspectives on context, we published this further evidence review on the importance of context.

Overcoming challenges to improving quality: Lessons from the Health Foundation's improvement programme evaluations and relevant literature (2012)

This research report provides a synthesis of learning from 14 of the Health Foundation’s improvement programme evaluations and sets this learning in its wider context.

References

- Health Foundation. Building the Foundations for Improvement. Health Foundation, 2015.

- NHS Improvement. Developing People, Improving Care. NHS Improvement, 2016.

- NHS Improvement. Shared Commitment to Quality. NHS Improvement, 2016.

- Care Quality Commission. Quality Improvement in Hospital Trusts: Sharing Learning from Trusts on a Journey of QI. Care Quality Commission, 2018.

- NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England, 2019.

- Bhattacharyya O, Blumenthal D, Schneider E. Small improvements versus care redesign: Can your organization juggle both? NEJM Catalyst, 10 January 2018.

- Health Foundation. Quality Improvement Made Simple. Health Foundation, 2013.

- Dixon-Woods M, Martin G. Does quality improvement improve quality? Future Hospital Journal. 2016; 3: 191–4.

- Dixon-Woods M. Harveian Oration 2018: Improving quality and safety in healthcare. Clinical Medicine. 2019; 19: 147–56.

- Health Foundation. Delivering a National Approach to Patient Flow in Wales: Learning from the 1000 Lives Improvement Patient Flow Programme. Health Foundation, 2017.

- Health Foundation. Skilled for Improvement? Learning Communities and the Skills Needed to Improve Care: An Evaluative Service Development. Health Foundation, 2014.

- Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, Testa L, Lamprell G. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. British Medical Journal Open. 2017; 7: e017708.

- Health Foundation. Some Assembly Required: Implementing New Models of Care. Health Foundation, 2017.

- Health Foundation. Partnerships for Improvement: Ingredients for Success. Health Foundation, 2017.

- Care Quality Commission. The State of Health Care and Adult Social Care in England 2016/17. Care Quality Commission, 2017.

- Care Quality Commission. Brief Guide: Assessing Quality Improvement in a Healthcare Provider. Care Quality Commission, 2018.

- Care Quality Commission. East London NHS Foundation Trust Inspection Report. Care Quality Commission, 2018.

- Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Quality Strategy 2018–21. Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 2018.

- Kaplan G, Patterson S, Ching J, Blackmore C. Why lean doesn’t work for everyone. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014; 23: 970–3.

- Blackmore C, Mecklenburg R, Kaplan G. At Virginia Mason, collaboration among providers, employers, and health plans to transform care cut costs and improved quality. Health Affairs. 2011; 30: 1680–7.

- Brown S. Virginia Mason: The Way Forward. Healthcare Finance, 2016.

- James B, Savitz L. How Intermountain trimmed healthcare costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Affairs. 2011; 30: 1185–91.