About the author

Andrew Haldane is Chief Executive of the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA) and was formerly Chief Economist at the Bank of England and a member of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Among other positions, he is Honorary Professor at the universities of Nottingham, Exeter and Manchester, a visiting Professor at King’s College London, a visiting Fellow at Nuffield College Oxford and a Fellow of the Royal Society and the Academy of Social Sciences.

Andy is Founder and President of the charity Pro Bono Economics, Vice-Chair of the charity National Numeracy, Co-Chair of the City of London Task-Force on Social Mobility and Chair of the National Numeracy Leadership Council. He has authored around 200 articles and four books.

About the REAL Centre

The Health Foundation’s REAL Centre (research and economic analysis for the long term) provides independent analysis and research to support better long-term decision making in health and social care.

Its aim is to help health and social care leaders and policymakers look beyond the short term to understand the implications of their funding and resourcing decisions over the next 10–15 years. The Centre works in partnership with leading experts and academics to research and model the future demand for care, and the workforce and other resources needed to respond.

The Centre supports the Health Foundation’s aim to create a more sustainable health and care system that better meets people’s needs now and in the future.

Acknowledgements

It is a great pleasure to be giving this year’s REAL Challenge lecture. Let me start by applauding the important work of the Health Foundation and in particular its Research and Economic Analysis for the Long Term (REAL) Centre, which supports improved long-term decision-making in health and social care. If there were ever a time to be keeping it REAL, it is now. I would like to thank Jennifer Dixon, Rebecca Mann and Anita Charlesworth for comments and suggestions on this lecture.

Introduction

This is a time of such flux: politically, economically, socially. Truth be told, I could probably have written that sentence at any time in the past two decades. Recently, the only constant has been change, the only certainty uncertainty. I suspect this uncertainty will continue for the foreseeable future. But rather than being a cause for pause, I believe strongly that uncertainty should instead be the prompt for action.

Let me start with a leading question. ‘Why is it always us?’ That was the plaintive cry from a weeping Sunderland football supporter during the Netflix documentary, and surprise hit, Sunderland ‘Til I Die. As a fellow Sunderland supporter – and sufferer – this expression has personal resonance. But it also has societal resonance given the sequence of nasty shocks to have hit our economies and societies over recent years.

These shocks have come thick and fast – from the global financial crisis to COVID-19 and to today’s cost-of-living crisis. All of these shocks were global in origin. But their effects were not felt evenly across countries. While everyone suffered – in lost jobs, incomes, lives and wellbeing – those losses have tended to be larger in the UK than elsewhere: more jobs and lives lost, greater hits to incomes and wellbeing. ‘Why is it always us?’

There are at least two alternative explanations. The first is misfortune. The UK has simply suffered a string of bad luck stretching back several decades. The UK has been a serial loser in life’s great lottery. The alternative hypothesis is that this run of bad results reflects not bad luck but bad management. By that I mean management of the economic, financial, health and energy systems on which we rely for societal success.

I believe the evidence strongly favours the second explanation. To argue by analogy – indeed, by health analogy – the UK is suffering from a weakened, and weakening, societal immune system. As with biological immune systems, this is constraining both our capacity to grow and our resistance to shocks. A weak societal immune system explains why the UK has suffered anaemic growth, has been more prone to shocks and why it has had longer subsequent periods of convalescence than elsewhere – and than in the past.

This weakened societal immune system in turn reflects a prolonged period of underinvestment in the sub-systems we rely on for growth and strength: from education and health care to housing and communities, to skills and innovation. Rebuilding the resilience of these sub-systems holds the key to a strengthened societal immune system overall and, with it, improved growth, greater shock resistance and higher wellbeing for individuals.

As society’s sub-systems are tightly coupled, each needs to be strengthened to secure system-wide success. As a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, a society is only as strong as its weakest sub-system. The UK’s health system’s lack of resilience has contributed to the UK’s weakened immune system. But without a strengthening of other economic and social systems this, while necessary, will by itself be insufficient to strengthen society’s immune system.

About this paper

Here, I discuss why the nation’s health and health care systems are central to society’s strength and growth. Health is best seen as a societal asset, an endowment or capital stock for the nation. It complements the other stocks of capital on which societal strength relies, from human capital (the skills of people), to physical capital (machines and technologies), to social capital (trust and relationships) to natural capital (our environment and ecologies).

For societal and economic success, these capitals need constant replenishment if they are to grow and remain resilient. The nation’s health endowment is no exception. In that sense, health is wealth – a societal endowment – albeit typically a non-financial endowment. It is an endowment that, other than at times of health crisis, has tended to be relatively under-emphasised in economic and social policy debate. COVID-19 could help correct that oversight.

I will also suggest, more tentatively, ways the resilience of health outcomes and systems might be strengthened. This is both a generational endeavour and an immediate priority. A generational endeavour because investing in health takes time, money and effort. But also an immediate priority because the fiscal and monetary policy sticking plasters of the recent past are running out of adhesiveness. It is time for system-wide surgery.

The next section describes and quantifies the links between health and the economy and how these have evolved over the distant and recent past. The following section runs diagnostic checks on the resilience of UK health and health care systems. The final section provides some suggestions for how this resilience might be bolstered. This is not a prescriptive list of remedies, but rather a set of directions of travel for policy debate.

Health and the economy

The links between health and the economy are many, various and two-way. Interlocking trends in economic and health performance have been pivotal in shaping the course of society, especially over the past 250 years. And trends in both economic and health performance over the past couple of decades, in particular, have emphasised closely intertwined weaknesses in the UK’s health and economic growth.

If you read a standard economics textbook, or the workhorse models of economic growth, these are notable for the absence of much explicit mention of health. Health is not a separate factor entering firms’ production decisions or households’ consumption decisions. If health is indeed an economic and societal endowment, it is often a largely invisible one in our standard frameworks for economic thinking and policy analysis.

Yet improvements in health and longevity have plainly played a huge role in contributing to the growth and success of our societies and economies for at least the past 250 years. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, living standards for the average global citizen have risen 15-fold, at an average annual rate of around 2.5%. This is a remarkable, and vertiginous, ascent in living standards and wellbeing.

It is all the more remarkable for the fact that those living standards, and measures of subjective wellbeing, had flatlined for several prior millennia. The Industrial Revolution marked a clear and defining inflexion point in society’s fortunes. It was accompanied by an equally remarkable fall in levels of global poverty, from around 95% of the global population 250 years ago to, on some measures, single digits today.

The two cylinders of economic growth

In explaining this transformation in fortunes, it is useful to decompose the growth potential of an economy into two components. Economic expansions can arise either because of growth in the workforce, which is then able to produce more goods and services; or from improvements in the capacity of that workforce to produce those goods and services – what is sometimes called productivity. Economic growth is a two-cylinder engine, where the cylinders are workforce activity and workforce productivity.

The key point is that health affects both growth cylinders. If chronic ill health results in people dropping out of the workforce, then it will shrink directly the supply of labour and hence the economy’s potential to grow – the first cylinder. For example, in the UK around 50% of those reporting themselves as long-term sick do not participate in the workforce, subtracting directly from labour supply and the UK’s economic potential.

But even if unwell people remain in the workforce, they are likely to produce less, including due to absences, reducing their productivity – the second cylinder. For example, Health Foundation funded research from the University of Sheffield suggests that the probability of experiencing reduced productivity at work doubles for those with physical health, and triples for those with mental health problems. A hit to health, then, is likely to lower both activity and productivity and, with it, the twin drivers of economic growth.

The inflexion point in global living standards after the Industrial Revolution can be traced to a take-off in both sources of growth relative to earlier centuries, with both a higher supply of workers and a higher rate of growth in their productivity, in roughly equal measure. That firing of both growth cylinders can, in turn, be linked in a significant sense to improvements in the health of the population over that period.

Improvements in health and life expectancy

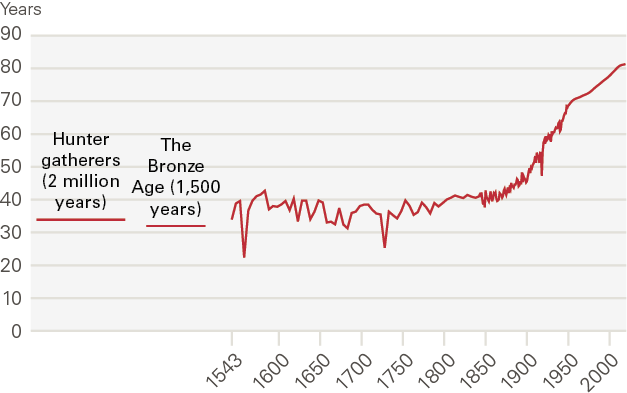

Since 1750, the UK’s population has risen, on average, around 2.3% per year having been essentially flat for several centuries prior. Accompanying, and contributing importantly, to that rise in the workforce were equally dramatic rises in longevity and life expectancy in the UK and elsewhere. Since 1750, average lifespans in the UK have more than doubled, from around 40 to above 80 years (see Figure 1). Rates of infant mortality have plummeted.

Figure 1: Life expectancy, UK, 1543–2019

Source: Our World in Data, Enlightenment Now

This step-change in health performance reflects not only medical advances but broader societal and economic advances too. Health systems improved alongside economic and societal systems in a virtuous loop. Nonetheless, it is clear improvements in health and health systems played a leading role in driving increases in the labour supply and, with it, growth in the economy after the Industrial Revolution.

Improved health probably also played a role in driving improvements in the productivity of the workforce over the period since 1750, which on average has risen around 0.8% per year. Alongside improved endowments of human capital and physical capital, improved physical and mental health contributed to improvements in workers’ productivity in the workplace. Recent studies have established a strong, bi-directional link between the two.

The remarkable story of the Industrial Revolution is often told in terms of advances in innovation and education – elements that do enter explicitly into the production functions beloved by economists. But accompanying advances in health and health care systems – some simple like clean water, some advanced like medicines – clearly contributed importantly to the rapidly expanding wealth of nations after the Industrial Revolution.

Flatlining health performance

After more than 200 years of almost uninterrupted rises, stretching right back to the Industrial Revolution, there are signs of a flatlining in the UK’s health performance over the most recent period. In the UK, this shift has been documented most clearly and comprehensively by Michael Marmot in two reports published a decade apart, in 2012 and 2022.,

The two Marmot reports pointed to a slowing of increases in healthy life expectancy (HLE) across the UK. In some of the UK’s most disadvantaged regions and among some of its most disadvantaged cohorts, there is evidence of falls in absolute levels of HLE, for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, mirroring US experience.

If history is any guide, we would fully expect these emergent health trends to show up in economic growth, operating through the twin cylinders of labour market activity and productivity. But as there are a number of trends at play here, affecting different cohorts of the population on different time horizons, it is useful to decompose these trends carefully when assessing their overall impact on economic growth.

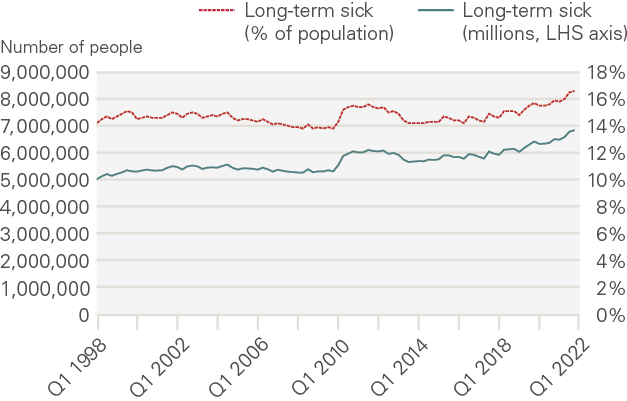

Mirroring Marmot’s evidence, Figure 2 shows that there has been a notable, if steady, rise in the reported incidence of long-term sickness in the UK working age population over the past two decades. This trend has gathered pace, notably since the COVID-19 crisis. People reporting long-term sick have risen by over a third since 2010, from 5.2 million to 7 million. Around 17%, or 1 in every 6 UK workers, now report as long-term sick.

Figure 2: Number and proportion of working-age population long-term sick, UK, 1998–2022

Source: ONS and Haskel J, Martin J (2022)

These are staggeringly high levels of reported ill health. The age distribution of this rise in ill health is also notable. While long-term illness has risen across all age groups, it has been most pronounced among those aged 16–24 years. Among this cohort, people reporting long-term sick rose around 50% between 2006 and 2021, to around 1 in 8. This is similar to levels reported by those aged 25–49 years.

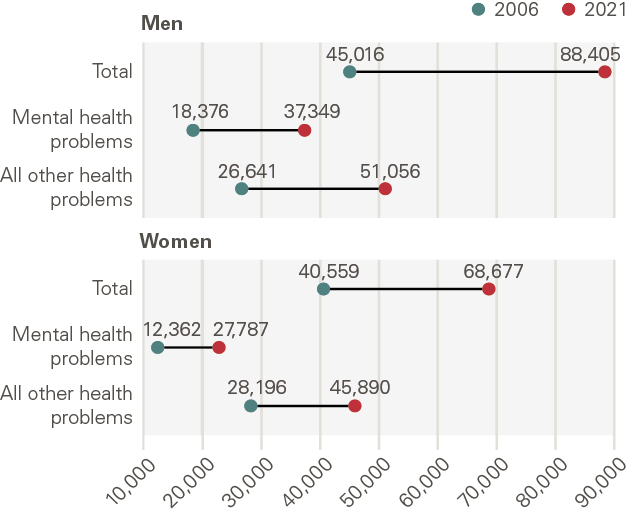

A deterioration of mental health appears to be the prime driver behind these trends. Two-thirds of young people who are inactive due to illness or disability have poor mental health. The number of young men inactive due to mental health doubled between 2006 and 2021 and young women saw a rise of over 80%. These trends are longstanding but were plainly made worse by COVID-19. I go on to discuss some of the causal factors, but the evidence points towards a range of underlying economic and financial factors.

Figure 3: Changes in economic inactivity due to mental health problems, UK, 2006 and 2021

Source: Resolution Foundation, Murphy L (2022)

Sickness and economic activity

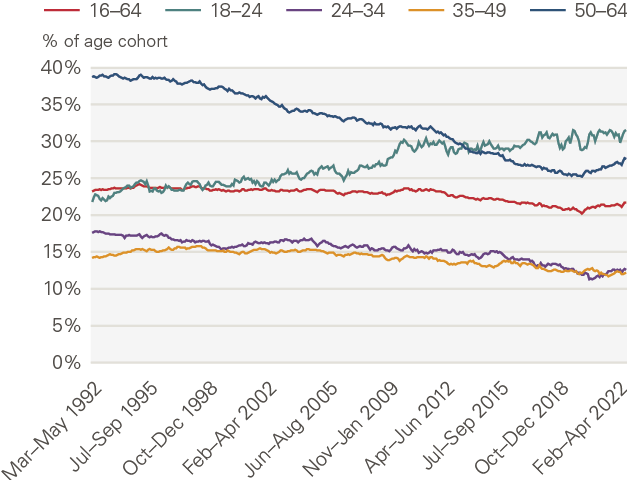

These trends in long-term sickness will have depressed participation and productivity in the UK workforce. And, given their skew towards the young, these trends could then have a potentially long-lived, generational impact on the drivers of economic growth. However, Figure 4 shows that in the period leading up to COVID-19, these trends in inactivity among the young were more than counterbalanced by trends at the opposite end of the age distribution.

In particular, over this period there was increased participation by those aged 50–64 years, especially women, helped by flexible working and rising retirement ages. Aggregate rates of inactivity fell up to 2019, reaching around 20% or 2 percentage points lower than in 2006. This is around 3 million extra people in the UK workforce.

Figure 4: Long-term trends in economic inactivity since 1992 by age of cohort, UK, 1992–2022

Source: ONS – Labour Force Survey (2022)

This rise in workforce participation was timely. Almost all of the growth in the UK’s economic potential since the global financial crisis has come courtesy of an expanding workforce, with very little from improved productivity. This, too, marks a sharp break from the past. Without the increased participation of older cohorts in the workforce up until 2019, even the anaemic rates of UK growth over the past two decades would probably not have been possible.

These growth patterns make the trends we have seen in participation since the COVID-19 crisis struck even more sobering. Since then, levels of inactivity among the 55–64 year old cohort have gone into reverse. In aggregate, around 650,000 fewer people are now in the UK workforce. Within this, increases in inactivity among the 55–64 age group account for around two-thirds of the rise since 2020.

Although these falls are not enormous by comparison with the pre-COVID-19 rises in participation, this is nonetheless a significant shift. It marks a reversal of the positive effect that labour supply has had on economic growth over the recent past. Or, put differently, the single cylinder of UK growth since the global financial crisis appears now to have risen. Were this to persist, it would add a further headwind to economic growth.

A number of recent studies have sought to explain this rise in inactivity among cohorts aged 50 years and older.,, The different survey methods and questions asked of respondents mean it is not possible to identify unambiguously a single definitive cause. Nonetheless, my reading is that a deterioration in health is a key, and most likely the single most important reason for this increase in economic inactivity among 50–64 year olds.

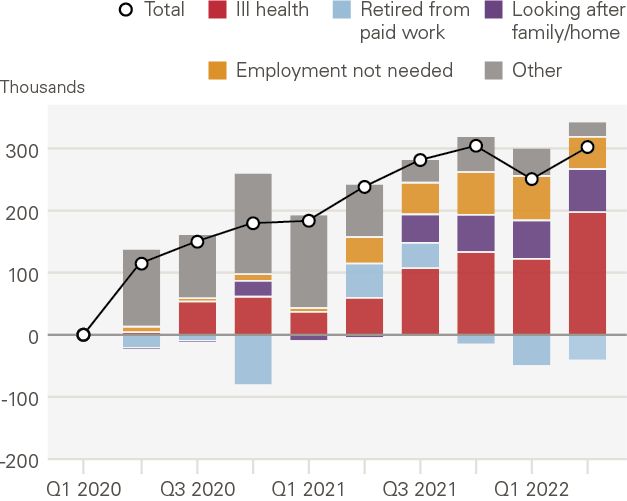

In surveys, directly reported ill health is the main reason given for inactivity among around half of those inactive older than 50 years (see Figure 5). As my former Bank of England colleague Jonathan Haskel has pointed out, however, this may understate the full effects of ill health. For example, a number of those citing retirement or looking after their families as the main reasons for leaving the workforce may have health as a secondary factor, either at the time or subsequently.,

Figure 5: Change in the number of 50–69 year olds inactive by reason, UK, 2020–2022

Source: The Health Foundation (2022)

These health concerns appear to reflect the combined effects of a number of factors, some immediate, some longer term. Long COVID-19 is thought to have affected around 80,000 of the UK workforce – significant, but not large enough to account for the fall in participation. Rising waiting lists and lengthening treatment times for other illnesses may also account for some of this rise, though this effect appears relatively modest.

A more comprehensive explanation is plausibly that we are seeing the consequences of longstanding rises in levels of long-term sickness before the pandemic, compounded by the effects of COVID-19. Consistent with this, the largest increases in ill health since COVID-19 are reportedly associated with cardiovascular and mental ill health – longstanding illnesses potentially made worse by COVID-19, tipping people into inactivity. Half a million working age people have impairing health conditions and, of those, 90% have not worked in over 3 years.

This tipping point behaviour is characteristic of complex systems. The effects of the COVID-19 shock may have had a disproportionate impact on illness and inactivity given the weak underlying health position of some cohorts. This points towards an underlying lack of resilience, or fragility, in UK health and health care, latterly exposed by COVID-19 – in much the same way the fragility of the financial system was exposed by the sub-prime shock 15 years ago.

This has added a second health-induced headwind to UK economic growth. The stalling of the UK’s productivity engine is now being compounded, rather than offset, by rising levels of inactivity and a contracting labour force. This shift in fortunes can already be seen clearly in record levels of unfilled job vacancies across every sector and every region and an escalation of wage pressures and industrial disputes. And while these trends are global, the rise in inactivity and accompanying rise in unfilled vacancies is larger in the UK than elsewhere around the world.

‘Why is it always us?’

We know the answer to this question. It appears to reflect long-term worsening in the UK’s health performance, amplified and exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19, generating a potential cascading adverse effect on both health and growth. In this way, health-induced trends in inactivity have worsened materially the cost-of-living crisis being experienced in the UK.

It is unclear whether these health trends will persist. But, on the balance of evidence, they are probably as likely to strengthen, given trends among younger people. Were they to do so, this would represent a significant, lasting headwind to UK economic growth, elongating the cost-of-living crisis. The UK’s health endowment may now be acting as a significant brake on economic growth, rather than the accelerator it has been for much of the past 250 years.

Of course, looking at health through the lens of economic growth alone potentially ignores some of the wider costs of ill health felt by individuals and society. It is important these are taken fully into account when scaling and solving the health challenges we face. The lived experiences of those suffering from long-term health problems is almost certainly better measured by subjective levels of life satisfaction, or wellbeing, than by incomes alone.

Empirical evidence clearly shows that ill health is one of, and often is the single most, important determinant of our wellbeing. This is particularly true of those with lowest levels of wellbeing to begin with., It should come as no surprise, then, that the number of adults reporting depressive symptoms doubled – from 10% to over 20% – during the COVID-19 crisis. And nor should it surprise us that, of those reporting these symptoms, around 85% believed the largest impact on their lives came through reduced wellbeing.,

This suggests that, however large the health-induced hit to growth and incomes, the hit to the wellbeing of individuals across the UK from chronic ill health is likely to have been significantly larger. This, too, points a lack of resilience in health outcomes and systems – a topic to which I now turn – and a corresponding weakening in our societal immune system.

Gauging the resilience of UK health and health systems

Having discussed the UK’s health performance, and its likely adverse impact on the economy, how robust or resilient are UK health and health care systems in tackling these problems? Given the tight coupling of health, economic and social systems, these systems are not confined to health and health care.

Resilience is often defined as the capacity of a system to deal with shocks without impairment of its core services and without putting undue strain on other supporting systems, including government. In 2008, the UK financial system plainly lacked resilience because, in the face of a global shock, it was unable to provide its core services of protecting people’s money and borrowing, and would have collapsed without large-scale government support.

How does UK health care fare on those criteria? As with financial and other complex systems, there is no singular metric to gauge resilience. One indirect metric comes from international comparisons of health performance. If we look at life expectancy, the UK occupies a mid-table position by OECD standards, though it is notable that most advanced Western economies sit above the UK, while those below are mostly emerging economies.

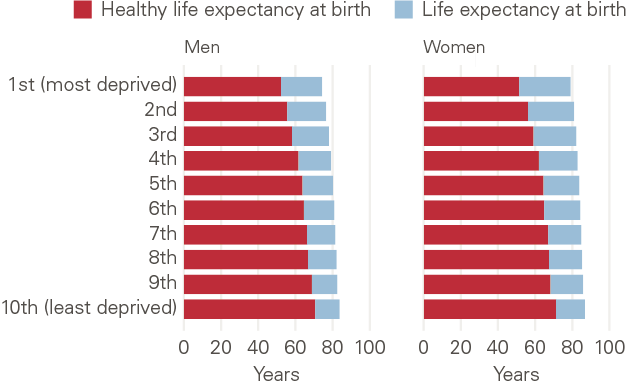

These aggregate data conceal significant distributional differences, however. Taking healthy life expectancy – a better measure of economic activity – there are striking distributional differences across income cohorts. HLE among the least deprived decile is around 15 years longer than for the most-deprived (see Figure 6). A man or woman in the most deprived decile spends around one-third of their lives in ill health, compared with around one-tenth for the least deprived.

Figure 6: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy by level of deprivation, men and women, Great Britain

Source: The Health Foundation (2022)

These distributional differences have an important age dimension too. Recent Health Foundation analysis uses Cambridge Multimorbidity Scores to show that differences in health performance increase most dramatically for those in the 50–64 year old cohort. This is also the cohort that has suffered the largest fall-off in activity recently.

These multimorbidity scores also make clear, however, that the seeds of health differences are sown early, and become more noticeable when people are in their 30s. From a relatively early age, health inequalities disadvantage poorer households and accumulate over time. This underscores the importance of preventative health, and improvements in economic and financial outcomes, if we are to improve health outcomes later in life for the most disadvantaged in society.

Health care systems

When it comes to health care systems themselves, one simple gauge of resilience is provided by spending. By comparison with other OECD countries, average spending on health per person in the UK is roughly around the average. Even then, however, it is notably less than Germany and most Scandinavian countries. And among G7 countries, the UK fares less well still, with the second lowest spend per head.

More broadly, however, average spending on health may tell us more about the efficiency of a health care system than about its resilience. Indeed, there may sometimes be a tension between the two. A system run in a highly efficient, cost-effective way may then lack the redundancy or slack needed to cope with unexpected shocks; it may lack resilience. Several diagnostics suggest this is a good characterisation of the UK health care system.

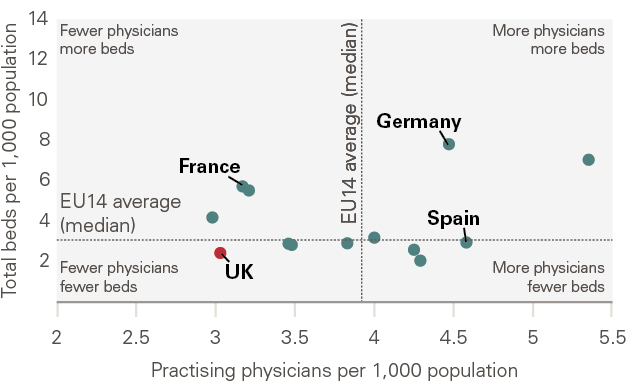

The resilience of any system is bolstered by investment. Over the past decade, investment in the UK health care system has lagged international comparators. By 2020, this meant the UK was operating with materially fewer doctors and beds per head of population than the OECD average (see Figure 7). The differences with economies such as Norway and Germany are now striking. The King’s Fund estimates that NHS hospital beds have fallen 50% over the past 30 years.

Figure 7: Doctors and beds per 1,000 population across developed economies, 2020 (or latest available)

Source: OECD Health Statistics (2022), REAL Centre

Improvements in adult social care are central to the issue of hospital beds and the resilience of the system. As older people account for an increasing share of the population, the system needs to adapt to this changing demographic. But over the past decade, age-adjusted annual spending per person on social care has declined and remains below levels in 2010 (in real terms).

This relative underinvestment in the UK health care and social care systems has, predictably, led to a lack of spare capacity in normal times but especially in abnormal ones. Even before COVID-19 struck, this could be seen in a variety of metrics such as lengthening waiting lists and waiting times. NHS waiting lists for elective care rose from 2.5 million in 2012 to 4.5 million on the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, a near-doubling.

The shock of COVID-19 has not just exposed those fragilities but significantly amplified them. Waiting lists now stand at around 7 million people,,, a near-tripling from a decade ago, although the true number may be less than that with double counting. Waiting times have also extended massively, with the number of people waiting over a year for treatment having risen to almost 400,000, from just over 1,000 as recently as 2019. It is reported that 1 in 6 UK adults have been unable to receive treatment, almost half of these cases being due to long waiting list times. This is almost triple the EU average. This points to a system fragile and at some risk of breaking in the event of another shock.

The effects of this on the experiences of both patients and NHS workers are also clear to see. Among patients, levels of satisfaction with the NHS have fallen to their lowest levels in 25 years. Among health care workers, almost half now report being ill due to work-related stress and 1 in 5 report high levels of depression., This is affecting recruitment, with 132,139 unfilled vacancies across the NHS, 10% of the planned workforce.

Looking to the future, most projections suggest this staffing fragility may increase. The Health Foundation estimates the workforce shortfall could reach around 160,000 by 2030/31, around 9% of projected staff demand. This suggests existing NHS care models will not be able to deliver 2018/19 standards over the coming decade without compromising on quality, safety, productivity and/or staff wellbeing.

Overall, then, this diagnostic evidence points in a consistent direction – a health care system whose underlying resilience is weak and weakening. This fragility has affected most acutely those most in need, whether by age or income.

Health inequalities

Of course, the resilience of the health care system cannot be gauged simply by looking at its own resilience but also those supporting sub-systems that shape and support health outcomes – economic and social, national and local. There is plenty of evidence these too have seen their resilience denuded over recent years, in ways that have compounded and contributed to health challenges.

Inequalities in health start at an early age, with higher rates of diagnosed mental health conditions, chronic pain and alcohol problems developing as early as the late teens and early 20s. These health inequalities then tend to grow over the life cycle through working and into old age. Levels of poverty among children are a key determinant of this life and health trajectory.

By international standards, the UK has one of the largest shares of children living in households in relative poverty. And government spending has not offset this trend: spending on children in the most deprived areas has decreased significantly over the past decade and, notably, is now no higher than in the wealthiest parts of the UK. This has contributed to an increasingly uneven playing field in health outcomes, seeding the rising incidence of long-term illness and inactivity at all life stages.

A compounding factor here, affecting most acutely younger and poorer households, has been rising levels of economic and financial insecurity. These insecurities have shown up in flat or falling levels of real pay, smaller pools of savings and weakened financial resilience, especially among the poorest households. These financial fragilities are being exacerbated currently by the cost-of-living crisis, which is also hitting hardest the poorest in society.

Research from the RSA suggests a direct and significant link between this rise in economic and financial insecurity and long-term health conditions, including mental health problems among younger people. There is a self-reinforcing cycle at work here, with low economic security worsening health and compounding economic insecurities due to more limited access to the jobs market. This helps explain the trends in long-term ill health and inactivity among the young.

Strengthening the resilience of UK health and health systems

Finally, I turn to what might be done to strengthen the resilience of the UK health care system and, with it, society’s immune system. How can the UK’s health endowment be replenished in ways that support individuals and the wider economy and society? Without being definitive, let me outline some of the potentially fruitful directions of policy travel, at a national and local level. They are offered in the spirit of constructive challenge, as this is a challenge lecture.

Measurement

The COVID-19 crisis brought home to everyone that what is not measured tends not to be managed. COVID-19 policy responses initially lacked coherence and timeliness, in some significant measure due to data deficiencies. As these were rectified, data were very quickly used to tailor real-time policy responses, to the point COVID-19 statistics soon came to dominate not only policy responses but media coverage too. A morbid fascination with COVID-19 statistics (in both senses of that word) set in among the public in part because, for over a year, COVID-19 statistics were the news.

The problem in the past has been the opposite. Health statistics have not always been reliably and comprehensively integrated into measures of societal success and hence into how policymakers act and the media report. Economic policy would be a case in point. Until COVID-19 struck, health considerations were rarely front and centre in economic policy debate and policy links between health and the economy were rarely forged.

One example of these health-related data deficiencies was discussed earlier. Despite piecing together the evidence, and conducting new surveys, it still is not possible to reach a clean and definitive conclusion on the impact of health issues in raising inactivity among 50–64 year olds. That is also true when it comes to understanding the links between young people’s mental health problems and labour market activity.

This suggests there is a strong case for thinking more systematically about how health data are collected, collated and integrated into policymaking, in peacetime as well as in health crises. Could real-time data on health be used more actively to help understand trends in the economy and society? Is there a case for integrating health data alongside other metrics of success, such as GDP and wellbeing, to tell a multi-lensed story? The REAL Centre could have a role in doing so.

Over the longer term, an extension of the national accounts or the national balance sheet might be needed. Health should be seen as a capital or endowment, in the same way as human, physical and social capital, and measured as such. National reporting should reflect the wealth, the health and the happiness of nations – the holy trinity. We are not yet there.

Stress testing

Even with the best measurement in the world, data alone can provide only an imperfect lens on the resilience of a system as complex as health care. Pushed to their extremities, these systems fracture. These fragilities were well illustrated during the COVID-19 crisis, as they were in finance during the financial crisis. Summary statistics on the pre-crisis millpond in these systems were often misleading diagnostics on the eventual tsunami.

The global financial crisis demonstrated that, to truly understand the resilience of a system, simulations under conditions of extreme stress are needed – so-called stress tests. These allow you to consider, in detail, the tail of adverse outcomes likely when crisis strikes. Stress tests of financial institutions are now standard practice across most financial jurisdictions. They are felt to be essential analytical tools in effective financial risk management.

The same approach is yet to be adopted comprehensively and systematically in health. During the COVID-19 crisis, stress testing was undertaken to determine the capacity of health care systems and identify possible break points. Indeed, that evidence was very influential in tailoring policy responses. But such stress testing is not as comprehensive and systematic when managing health risk in peace as well as wartime.

This is an important gap, and will become more so the greater the distance from the COVID-19 crisis. There is a natural tendency to look for efficiency savings during periods of calm, savings that may reduce the resilience of a system over time. That was a common lesson from both the COVID-19 and global financial crises. With hindsight, too great an emphasis was placed on system efficiency and too little on system resilience in both health and finance. The result was ineffective risk management.

System-wide stress testing is a bulwark against those risks. Health should heed the lessons of finance, putting in place regular and comprehensive health care stress testing and making these results available publicly for debate. It is important, as with finance, this process is conducted rigorously and independently. Indeed, the Health Foundation might itself have a role to play.

Devolution

Local decisions are often best taken locally, for reasons of information and agency. Health is no exception. Yet at present across England, only Greater Manchester has been devolved local powers over health, although a number of other places are now seeking these powers. In doing so, experience in Greater Manchester provides a useful case study of the potential effects of devolving health care powers.

A recent article in the Lancet explores the impact of Greater Manchester health devolution on life expectancy in the region. It finds positive outcomes. Though the precise reasons are still to be identified, this is encouraging evidence on the importance of tailoring local responses to local health needs – a lesson familiar from other policy domains. It would support the widening of health care powers to other regions, not least to learn from their experiences.

Policy integration

As a tightly coupled system, it is clear that tackling health problems requires actions well beyond the health care system itself. A system-wide approach, embracing economic and social systems, is needed to tackle health problems and their spill-over effects beyond health.

Initiatives such as social prescribing, championed by Sam Everington and Andrew Mawson, winners of this year’s RSA Albert Medal, are an example of this joined-up approach. This involves using non-clinical approaches to tackling health problems, often at the hyper-local or community level. Having been trialled successfully in a number of places, this approach has now been endorsed by the NHS and is being taken forward by a number of countries internationally too.

Implementation on the ground remains, however, patchy across the UK. This partly reflects lack of money and partly a lack of incentives and information. Either way, given the worrying trends in physical and in particular mental health across the UK, alongside the pressures on the NHS and on the government’s finances, it would be hard to think of a better time to be rolling out social prescribing more comprehensively across the UK.

There is a link to devolution too. Joined-up policy at the national, or Whitehall, level is devilishly difficult. Examples of joined-up policy are rare. Success in joined-up policymaking is far more likely, however, at the local level, where there are a manageable numbers of local anchor institutions to coordinate. Across a few UK regions, I have seen that joined-up policy approach being put into practice.

A similar approach is being pursued by Michael Marmot through so-called ‘Marmot cities’ and ‘Marmot towns’. There are currently seven of these across the UK. They too are an example of system-wide approaches to tackling health-cum-economic-cum-social challenges, at the local level. Internationally, New Zealand has also developed integrated approaches to health.

Placemaking

The UK has wide and widening geographic differences. Health is typically felt to be both a cause and a consequence of these inequalities. In the white paper on levelling up published by the UK government earlier this year, a specific mission was assigned to health outcomes to reflect that. This sought to both raise HLEs and shrink differences in HLEs across different parts of the UK. Improved health is now central to UK placemaking. That has rarely, if ever, been the case in the past.

There is a second key role for health care when it comes to placemaking. The NHS often serves as an anchor institution in places, including as a large employer and generator of income. That anchor role tends to be more important, and the contribution of the NHS larger, the poorer the place. This underscores the foundational role of health care systems in transforming places for the better.

Food standards

The link between diet and health is well established. In 2021, Henry Dimbleby published a report for the government on national food standards, laying out this evidence comprehensively and compellingly. The report also made a sequence of wide-ranging recommendations about measures to improve the security and sustainability of the food system and boost food standards.

Among the Dimbleby report’s health-facing recommendations were: a sugar and salt tax; mandatory reporting by large food companies; an ‘Eat and learn’ initiative in schools; and more active use of the government’s procurement policies to support healthy eating and food production.

In 2022, the UK government published its response to the Dimbleby review, a National Food Strategy. This included proposals to improve transparency around health reporting on foodstuffs, a food curriculum in schools and supporting interventions to encourage healthier diets. It fell well short of the Dimbleby proposals, however, focusing on individual responsibility rather than putting in place across-the-board measures to protect public health.

The ongoing cost-of-living crisis makes this a difficult time to be raising the price of some foodstuffs. Nonetheless, the case for implementing the Dimbleby recommendations in full, in a phased fashion, remains compelling. Some of the measures are needed to build resilience in food supply chains, reducing pressures on the future cost of living. Others would deliver a medium-term benefit not only to consumer health but to the government’s fiscal position. This is a classic case where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound (in both the body mass and financial sense) of cure.

Education

Given the strong skew of health spending currently towards end-of-life treatment and care, it is possible too little resource is currently being invested in young people’s physical and mental health. If so, this may well also be a false economy, allowing preventable or curable illnesses to have a larger and more lasting impact on individuals’ lives and society at large.

Investing more in education around health, from the earliest years, would be one way of turning this tide. Some progress has been made in schools, including through the introduction of PSHE. And the RSA has itself long had an interest in education and health, including through its Focus on Food campaign in the 1990s. The Dimbleby proposals, if implemented, would take us further in that direction.

One idea suggested recently by Sam Everington and Andrew Mawson is to have a dedicated health care professional in every school across the UK. Like the role of a GP, their role would be to develop a community of practice around health, attuned to the needs of students, their parents and the locality. They would offer clinical, social and pastoral support, depending on children’s needs, as well as helping educate about good health and diet.

This ‘nurse in every school’ initiative is an attractive one for helping tackle health inequalities in those communities and for those children most in need, from the early years onwards. It is one the RSA might seek to support through its own education activities and schools programme.

Business

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted for many companies the crucial importance of the health and wellbeing of staff for running their companies effectively. For example, surveys of staff wellbeing and measures to deal with health-related pressures on staff expanded rapidly during COVID-19. It is important these business lessons are not lost as COVID-19 abates, as recent work by Cary Cooper has emphasised.

There are some signs this is happening. For example, the CBI has positioned health as one of its six key ways to transform the economy. They have developed a health index to measure businesses’ contribution to health and to promote the role of business in improving national health.

One potentially fruitful strand might be to embody health issues in corporate ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) reporting. For example, the insurance company Legal and General, working with Michael Marmot, has suggested ways businesses can contribute to improved health in the workplace and beyond.

There is also a crucial role for business, working with government, to think imaginatively about how they encourage more people, either inactive in the workforce or long-term sick, to return or contribute in future. This might include tax incentives, flexible working schemes and retraining initiatives. This would in principle deliver a twin-win, for individuals in income terms and for the economy in tackling acute staffing shortages.

Fiscal finances

When it comes to public finances, there are many hard choices about where future savings are best made. One element of those hard choices is how budgets are divided between current spending (RDEL) and capital spending (CDEL), consumption versus investment. RDEL keeps the lights on today, CDEL ensures they stay on tomorrow.

This distinction is useful in ensuring sufficient investment is made in future growth. Equally, it is important statistical distinctions are not drawn too sharply because they do not always translate into wise long-term choices from a growth perspective. Health spending is a case in point. Education spending would be another.

Spending on doctors and nurses is RDEL. But this spending is contributing importantly to the UK’s health endowment, its stock of capital, just as spending on teachers contributes to human capital. If this capital were recognised in the national accounts, there would be a case for reclassifying some health spending as capital not current, since it boosts the UK’s health endowment and, with it, future growth.

Adhering to something like a fiscal golden rule – only borrowing to finance investment spending – has great attractions. But that does rely on meaningful distinctions between spending categories that, for health (and some other spending categories such as education), may not always exist. A whole-system approach to policy, to strengthen our societal immune system, might call for a modified golden rule.

The deep causes of the rise in mental health problems facing a rising fraction of young people seem to be strongly related to growing economic and financial insecurities. These are insecurities that the existing social safety net appears not to have mitigated, at least not fully. It is worth thinking imaginatively about what else might be done to do so.

The RSA has done work looking at the role a Universal Basic Income (UBI) might play in addressing these insecurities and their health costs. A large number of UBI pilots are underway, including in Scotland and Wales and a number of countries around the world, to explore their design and success. Other new social safety net solutions are also worth exploring. Rigorous experimentation and evaluation will be key to drawing meaningful conclusions about the design and efficacy of these schemes.

Conclusion

Health matters to the wealth of our nations and the wellbeing of our citizens. Indeed, it has rarely mattered more. Trends in health performance across the UK, among both young and old, suggest a lack of resilience in health outcomes and systems. This is having increasingly visible and material side effects, from lower growth to staff shortages, from increased vulnerability to shocks to increased precariousness in fiscal finances.

Without policy change, these health problems will worsen and society’s immune system will weaken further. Building greater resilience in health and health care calls for multi-year, multi-pronged reform to strengthen society’s tightly coupled sub-systems, including health. It calls for system-wide surgery. I have offered some reflections on how this might be achieved, many at low cost.

‘Why is it always us?’ With the right reforms, next time it need not be.

References

- Bryan M L, Bryce A M and Roberts J. Presenteeism in the UK: Effects of physical and mental health on worker productivity. University of Sheffield; 2020.

- Bevan S, Cooper C L. The healthy workforce: Enhancing wellbeing and productivity in the workers of the future. Emerald; 2022.

- Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, Goldblatt P, Morrison J. Health equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 years on. Institute of Health Equity; 2020.

- Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). Institute of Health Equity; 2010.

- Haskel J, Martin J. Economic inactivity and the labour market experience of the long-term sick; 2022 (epub ahead of print).

- Tinson A, Major A, Finch D. Is poor health driving a rise in economic inactivity? The Health Foundation; 2022 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/is-poor-health-driving-a-rise-in-economic-inactivity).

- Boileau B, Cribb J. Is worsening health leading to more older workers quitting work, driving up rates of economic inactivity? IFS; 2022 (https://ifs.org.uk/articles/worsening-health-leading-more-older-workers-quitting-work-driving-rates-economic).

- Dawson A, Phillips A. Understanding ‘Early Exiters’: A Case for A Health Ageing Workforce Strategy. Demos; 2022.

- Strauss D. Why are Britain’s over-50s really leaving the labour market? Financial Times; 2 November 2022 (www.ft.com/content/125df3f1-b0c0-4a5b-bf96-9bca0fc06404).

- ONS. Understanding well-being inequalities: Who has the poorest personal well-being? ONS; 2018 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/understandingwellbeinginequalitieswhohasthepoorest personalwellbeing/2018-07-11).

- ONS. Personal and economic well-being: what matters most to our life satisfaction? ONS; 2019 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/personalandeconomicwellbeingintheukwhatmatters mosttoourlifesatisfaction).

- ONS. Employment in the UK: October 2022. ONS; 2022 (www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/employmentintheuk/october2022).

- ONS. Reasons for workers aged over 50 years leaving employment since the start of the coronavirus pandemic: wave 2. ONS; 2022b (www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/reasonsforworkersagedover50years leavingemploymentsincethestartofthecoronaviruspandemic/wave2).

- Watt T, Raymond A, Rachet-Jacquet L. Quantifying health inequalities in England. The Health Foundation; 2022 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/quantifying-health-inequalities).

- Ewbank L, Thompson J, McKenna H, Anandaciva S and Ward D. NHS hospital bed numbers: past, present, future. The Kings Fund; 2021 (www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-hospital-bed-numbers#how-does-the-uk-compare-to-other-countries).

- Morris J, Reed S. How much is Covid-19 to blame for growing NHS waiting times? Nuffield Trust; 2022 (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/how-much-is-covid-19-to-blame-for-growing-nhs-waiting-times).

- BMA. NHS backlog data analysis. BMA; October 2022 (www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/nhs-backlog-data-analysis).

- Hacker J. 1.5 million duplicates on elective waiting lists, NHSE estimates. Healthcare Leader; 3 November 2022 (https://healthcareleadernews.com/news/1-5-million-duplicates-on-elective-waiting-lists-nhse-estimates).

- Burn-Murdoch J. Britons now have the worst access to healthcare in Europe, and it shows. Financial Times; 4 November 2022 (www.ft.com/content/de8fc348-0025-4821-9ec5-d50b4bbacc8d).

- Gilleen J, Santaolalla A, Valdearenas L, Salice C, Fusté M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and well-being of UK healthcare workers. BJPsych Open. 2021; 7(3): E88.

- Edwards N, Cowper A. Fronting up to the problems: what can be done to improve the wellbeing of NHS staff? Nuffield Trust; 2022 (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/fronting-up-to-the-problems-what-can-be-done-to-improve-the-wellbeing-of-nhs-staff#:~:text=The%20only%20longitudinal%20analysis%20of,with%205%25%20before%20the%20pandemic).

- NHS. NHS Vacancy Statistics England April 2015 – June 2022 Experimental Statistics. NHS; 1 September 2022 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-vacancies-survey/april-2015---june-2022-experimental-statistics).

- ONS. The rising cost of living and its impact on individuals in Great Britain: November 2021 to March 2022. ONS; 2022 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/expenditure/articles/therisingcostoflivinganditsimpactonindividualsingreatbritain/november2021tomarch2022).

- Webster H, Morrison J. Briefing document: Economic security and long-term conditions. RSA; 2021.

- Britteon P, Fatimah A, Lau Y-S, Anselmi L, Turner A J, Gillibrand S, Wilson P, Checkland K, Sutton M. The effect of devolution on health: a generalised synthetic control analysis of Greater Manchester, England. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7: e844–52

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. Levelling Up the United Kingdom. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities; 2 February 2022 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom).

- Dimbleby D. National Food Strategy: Independent Review. National Food Strategy; 2021 (www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/the-report).

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Government food strategy. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs; 13 June 2022 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-food-strategy).

- Cooper C, Hesketh I (eds). Managing workplace health and wellbeing during a crisis: How to support your staff in difficult times. Kogan Page; 2022.

- Business for Health. Business Framework for Health: Supporting businesses and employers in their role to enhance and level up the health of the nation. Business for Health; 2022.

- Institute of Health Equity. The Business of Health Equity: The Marmot Review for Industry. Institute of Health Equity; 2022.

- Johnson E, et al. Levelling the mental health gradient among young people: How Universal Basic Income can address the crisis in anxiety and depression. RSA; July 2022.