Key points

- A key question for any future inquiry into the government’s handling of COVID-19 will be how well government protected people using and providing adult social care.

- COVID-19 has had a major and sustained impact on social care in England. There have been 27,179 excess deaths among care home residents in England since 14 March 2020 (a 20% increase compared with recent years), and 9,571 excess deaths reported among people receiving domiciliary care since 11 April 2020 (a 62% increase). Social care staff have been at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than others of the same age and sex. The wider health impacts – from reduced access to care, social isolation, increased burden on carers – are harder to measure but also significant.

- The policy response to COVID-19 is complex and evolving. Challenges in protecting people who use and provide social care during the pandemic have not been unique to England. The task of protecting social care is closely tied to the broader task of protecting the population from COVID-19.

- During the first wave of the pandemic, central government support for social care in England was too slow and limited, leading to inadequate protection for people using and providing care. In this briefing, we analysed national government policy on adult social care in England after the first wave of COVID-19 – between June 2020 and March 2021.

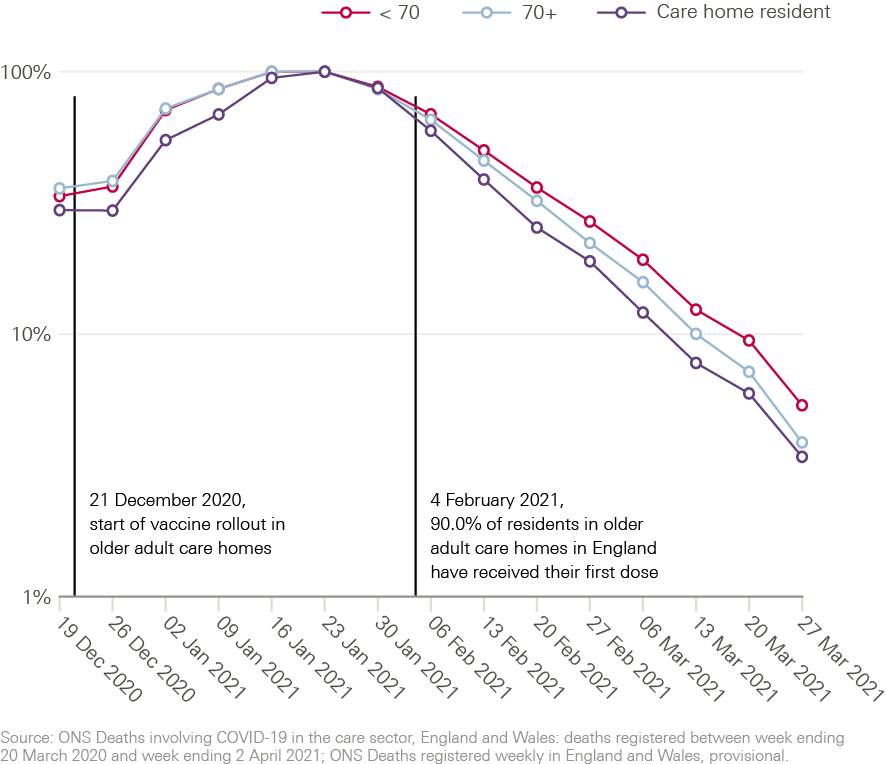

- Overall, we found a mixed picture. Support in some areas improved, such as access to testing and PPE, and the priority given to social care appeared to increase. Groups using and providing social care were prioritised for COVID-19 vaccines, alongside the NHS. This is likely to have offered much greater protection to care home residents and others.

- But major challenges remained. Government policy on social care was often fragmented and short-term, creating uncertainty for the sector and making it harder to plan ahead. And policies in key areas, such as on regular testing in social care, still came slowly – including over the summer of 2020, when COVID-19 outbreaks continued to occur in care homes, despite very low prevalence of COVID-19 in the community.

- There have also been persistent gaps in the national policy response, including support for social care staff and people providing unpaid care. Government policy also risked leaving out people using and providing care in some settings, including younger adults with learning disabilities and autism. These gaps risk exacerbating inequalities.

- A lack of publicly available data means that we only know so much about the impacts of the pandemic on social care, and the success of policies to support the sector. Data on care provided outside care homes are limited and hard to interpret. This is concerning, given the sustained increase in mortality reported among people receiving care at home.

- Major structural issues in social care have shaped the policy response and effects of COVID-19 on the sector. These include chronic underfunding, workforce issues, system fragmentation, and more. COVID-19 also appears to have made some longstanding problems worse, such as unmet need for care and the burden on unpaid carers. The longstanding political neglect of social care in England has been laid bare for all to see. Continued neglect would leave the system vulnerable to future shocks.

- Fundamental reform of adult social care in England is needed to address the longstanding policy failures exposed by COVID-19. This reform must be comprehensive and long-term – not narrowly focused on preventing older people selling their homes to pay for care. Immediate policy action and investment is also needed to support the system to recover from the pandemic and prepare for potential future waves of COVID-19.

Introduction

England is slowly emerging from its third national lockdown and numbers of daily COVID-19 hospitalisations and deaths have fallen considerably since late January 2021. But people across the country have been hit hard by COVID-19. Excess deaths during the pandemic in 2020 were among the highest of any country., Total deaths directly related to COVID-19 have passed 112,000 in England alone.

The impacts of COVID-19 on people using adult social care – adults of all ages who need care and support because of disability and illness – have been significant. By 2 April 2021, there had been 27,179 excess deaths among care home residents in England since the start of the pandemic. And there had been 9,571 excess deaths reported among people receiving domiciliary care since 11 April 2020 – an increase of 62% compared with recent years. Social care staff have been more likely to die from COVID-19 than others of the same age and sex. The burden on unpaid carers – mostly women – has increased, affecting their health.,,

The national policy response to COVID-19 is complex and evolving.,, Policy decisions have been made in an urgent and uncertain context. But it is clear that there have been major problems with the government’s approach to supporting adult social care in England.,,,, During the first wave of the pandemic, social care services experienced shortages and slow access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing, insufficient financial and other support, and relative neglect by policymakers in favour of the NHS. Overall, our assessment – based on analysis of policies between 31 January and 31 May 2020 – was that government did too little too late to protect people who use adult social care and those who care for them.

The government’s policy response to COVID-19 has been shaped by underlying structural factors. The social care system that entered the pandemic was underfunded, understaffed, and undervalued. Funding per person adjusted for age fell by 12% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2018/19. Fewer people are receiving support from local authorities, despite rising needs. Workforce shortages going into COVID-19 were estimated at 122,000. And many social care staff work for low pay and under poor terms and conditions. The organisation of social care in England is also complex and fragmented., Successive governments have promised reform of England’s broken system of social care and support, but none have delivered it.

In this briefing, we analyse central government policies on adult social care in England after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic – from 1 June 2020 to 28 February 2021. This includes policies to support adult social care during the height of the second wave of the pandemic in January and February 2021, and in the months leading up to it. We provide a narrative summary of central government policies related to adult social care in different areas, such as policies on testing and support for the workforce. Where possible, we use publicly available data to describe how these policies were implemented. We also provide a summary of the latest publicly available data on the impacts of COVID-19 on adult social care. In the final part, we make an assessment of the policy response following the first wave, consider how policies changed over time, and identify priorities for the future.

* For excess deaths among care home residents, we compared deaths to the 5-year average (2015–2019). For excess deaths among people receiving domiciliary care, this was compared to the 3-year average (2017–2019).

† The number of excess deaths for the whole period (since the start of the pandemic) is lower than the number of excess deaths in the first and second waves combined, depending on when the start and end date of these two waves are defined (and if this definition involves a gap between the two waves). During July and August 2020 – what we have taken as the period in between the two pandemic waves – there were fewer deaths than expected, so this decreases the total for the whole pandemic period.

Approach and methods

We analysed national government policies on adult social care in England related to COVID-19 between 1 June 2020 and 28 February 2021. Our analysis also includes a small number of policy developments that took place after February 2021, if we thought this was needed to understand or reflect the policies we reviewed. We also refer to key social care policies introduced during the first stage of the pandemic response – between 31 January 2020 and 31 May 2020 – which are described and assessed in more detail in our previous analysis.

We focused on policies introduced by central government directly related to social care. We did not review guidance or policies affecting social care from national organisations outside government, such as the Local Government Association or major social care charities. We also excluded policies or approaches of individual local authority areas or care providers. Nor did we analyse the wider support that may have been available for care providers through government loans, tax holidays, and other interventions to support businesses. As a result, our analysis only focuses on a limited part of the policy response to support social care.

Our analysis is based on publicly available data and evidence. To identify and understand relevant policies, we reviewed government policy documents, press releases, ministerial speeches, letters, guidance documents, web pages, and other sources. Much of these data are compiled in our COVID-19 policy tracker – covering national policy developments in England in 2020. We used this database as a starting point, before searching government and other websites for additional information. Some policy documents were retrospectively removed from government websites or updated on the same webpage without clear descriptions of what had changed, so we used the Wayback Machine digital archive and other sources to help understand how policy changed over time. To understand how these policies have been implemented, we drew on government announcements, select committee sessions, official statistics, statements from social care organisations or leaders, and other sources. These data are limited and therefore our analysis provides an incomplete picture.

Finally, to understand the impacts of the pandemic on adult social care users and staff, we synthesised findings from relevant studies and analysed publicly available data from official sources, including the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and Care Quality Commission (CQC), as well as surveys from ADASS, Carers UK, and others. We held a workshop discussion with 11 social care experts and sector leaders in March 2021 to test the findings from our analysis of the national policy response.

Box 1: The structure of adult social care in England

Adult social care is the care and support provided to people who need it because of disability, illness, or other life circumstances. The kind of support that people receive varies widely depending on their needs – from help washing and dressing, to transport services, day centres, and help with employment or volunteering opportunities.

People might receive social care in a mix of settings, including:

- care homes (including residential or nursing care homes)

- domiciliary care (supporting an individual living in their own home)

- day care or community care (such as community outreach and support for carers).

Care services are provided by around 18,200 organisations working in 38,000 locations.

Around 842,000 adults received long-term support from local authorities in England in 2018–19. 35% were younger adults (aged 18–64) and 65% were older people (aged 65 and older). About one-third were supported in nursing and residential homes, but most people received care in the community (including in their own homes). Others go without care, privately purchase their care, or turn to family and friends for unpaid support.

The NHS and social care are commissioned and funded separately. Publicly funded social care is commissioned by 151 local authorities, who receive a grant from central government. National policy responsibility for social care rests with the Department of Health and Social Care. Responsibility for local authority finances and other issues sit with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The Care Act 2014 defines local authorities' responsibilities to assess people’s care needs and eligibility for publicly funded support – and describes the core purpose of adult social care as promoting individual wellbeing. The CQC regulates social care providers and agencies.

An estimated 1.5 million people undertake paid roles in adult social care in England. There are chronic workforce problems in the sector, and terms and conditions are poor. Pay is low (for example, the mean annual pay for care workers in the independent sector is £16,900 per year), turnover is high (around 430,000 leave their job each year), and a quarter of staff are on a zero-hours contract. An estimated 13.6 million adults provide unpaid care in the UK (4.5 million of whom started caring as a result of the pandemic).

‡ Analysis code is available via GitHub (https://github.com/HFAnalyticsLab/COVID19_social_care_open_data).

Policies on social care after the first wave of COVID-19

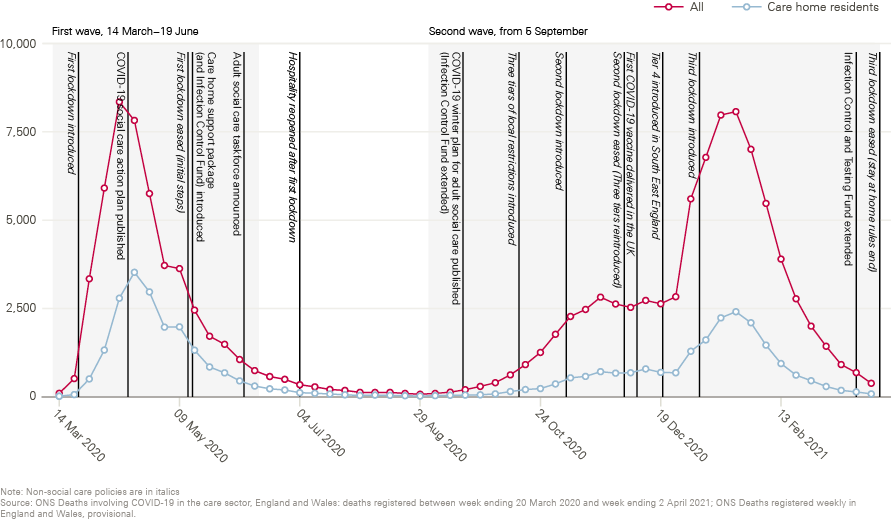

Government’s approach to supporting adult social care has evolved over the course of the pandemic. COVID-19 cases and deaths have varied widely over 2020 and early 2021. And policies on social care have interacted with wider national COVID-19 restrictions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Deaths involving COVID-19 among the general population and care home residents in England, by week reported, with national and social care policy milestones

Table 1 provides a summary of key national policies on social care introduced in England between June 2020 and February 2021. Some policies introduced during the first wave, such as on national recruitment of social care staff, have been continued or extended (see Appendix 1 for a summary of national policies on social care during the first wave). Policies in other areas have been revised or developed in response to the changing pandemic context, such as improvements in testing capacity and the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines.

Table 1: Summary timeline of key events and social care policies, June 2020 to February 2021

|

Summary |

Date |

|

Whole care home testing expanded to all care homes |

7 June 2020 |

|

Social care sector COVID-19 support taskforce announced, led by David Pearson and reporting to the Minister of State for Care. Purpose is to ensure the delivery of existing government support and advise on a plan ‘over the next year’ |

8 June |

|

Fourth easing of first lockdown in England (hospitality reopened) |

4 July |

|

Regular testing strategy introduced for staff and residents in care homes for older people and those with dementia |

6 July |

|

‘The next chapter in our plan to rebuild: The UK Government’s COVID-19 recovery strategy’ published |

17 July |

|

Guidance on visiting care homes during COVID-19 published |

22 July |

|

NHS Continuing Healthcare reintroduced (from 1 September) alongside new discharge to assess approach, supported by £588m |

21 August |

|

Regular testing programme expanded to all adult care homes |

31 August |

|

‘Rule of six’ introduced |

14 September |

|

COVID-19 winter plan for adult social care published, including £546m to extend the Infection Control Fund and a commitment to providing free PPE for care homes and home care providers until the end of March 2021 |

18 September |

|

Social care COVID-19 support taskforce report published (alongside reports from eight advisory groups on different policy areas) |

18 September |

|

Coronavirus Act 2020, including the Care Act easements, extended |

30 September |

|

Primary care networks required to implement enhanced healthcare in care homes service |

1 October |

|

Hospitals required to discharge COVID-19 positive patients to ‘designated care settings’ |

13 October |

|

Three-tiered system of local COVID-19 alert levels introduced (visits to care homes in Tiers 2 and 3 limited to exceptional circumstances) |

14 October |

|

Second lockdown introduced (guidance recommends maintaining options for outdoor or ‘screened’ visits to care homes) |

5 November |

|

Easement to Carer’s Allowance to allow those self-isolating to continue receiving it extended to May 2021 |

12 November |

|

Consultation on legislation to ban staff movement between settings launched |

13 November |

|

Weekly COVID-19 testing expanded to registered home care workers |

23 November |

|

‘COVID-19 winter plan’ published |

23 November |

|

Spending Review 2020 |

25 November |

|

Guidance published on care home visits supported by lateral flow testing (and additional PPE), and on outwards visits for younger adult residents |

1 December |

|

Second lockdown ends, return to tiered approach |

2 December |

|

First COVID-19 vaccine approved |

2 December |

|

Regular testing for eligible extra care and supported living services announced |

7 December |

|

First COVID-19 vaccine delivered in the UK |

8 December |

|

Plans for Christmas easements to restrictions changed and Tier 4 introduced in South East England (outdoor or ‘screened’ visits only in Tier 4 care homes) |

21 December |

|

COVID-19 vaccinations rolled out in care homes |

21 December |

|

£149m adult social care rapid testing fund introduced to support care home testing |

23 December |

|

Updated Joint Committee on Vaccines and Immunisation (JCVI) advice on priority groups for COVID-19 vaccinations published |

30 December |

|

Free PPE commitment extended until June 2021 |

January 2021 |

|

Third lockdown introduced (outdoor or ‘screened’ visits for all care homes) |

6 January |

|

£120m workforce capacity fund for staffing and testing announced |

17 January |

|

NHS announces it has offered first doses of the COVID-19 vaccine to all care homes |

1 February |

|

Weekly testing for day centre workers announced |

1 February |

|

New recruitment campaigns for short and long-term social care work announced |

9 February |

|

UK COVID-19 vaccine uptake plan published |

13 February |

|

Government announces it has met its target to offer first doses of the COVID-19 vaccine to all care home residents and staff, health and social care workers, people aged 70 and older, and the clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV). |

15 February |

|

Weekly testing extended to personal assistants |

17 February |

|

Care home visiting guidance updated to allow one named visitor per resident from 8 March |

20 February |

|

Roadmap to ease national lockdown published |

22 February |

Source: COVID-19 policy tracker, Gov.uk, NHS England website, Wayback Machine

The government’s adult social care winter plan, published in September 2020, provided the main narrative for the government’s approach to supporting social care going into winter 2020/21. This plan was combined with a long list of guidance and policy documents on testing, care home visiting, and other areas that were published and updated regularly.

The government’s approach after the first wave was supported and informed by a national social care ‘taskforce’ (alongside advice from SAGE and others). Government established the taskforce – led by David Pearson, an experienced social care leader – in June 2020, to oversee implementation of some national COVID-19 social care policies, and provide advice to government on the support needed for the sector ahead of winter 2020/21. The taskforce produced a report in September 2020 with recommendations for policy. Government adopted many of these recommendations in its social care winter plan – for example, by offering free PPE to social care over winter (see section on infection prevention and control). But others were not adopted, and several lessons or issues identified by the taskforce – for example, the need for government to boost its expertise and capacity on social care policy – are less amenable to quick fixes.

In this section, we analyse the main national policies introduced on adult social care in the pandemic between June 2020 and February 2021, focusing on the following areas:

- COVID-19 testing

- support for staff and unpaid carers

- infection prevention and control

- COVID-19 vaccines

- interaction between social care and the NHS

- oversight of adult social care.

We provide a narrative overview of policies in each area and data on their implementation.

COVID-19 testing

Lack of access to COVID-19 testing was a major problem for social care at the start of the pandemic. Social care workers and care home residents with COVID-19 symptoms were only guaranteed access to tests in mid-April 2020. As testing capacity increased, the Minister for Care stated that government prioritised social care.32 Programmes to test care home staff and residents without symptoms were introduced in summer 2020, and later extended to other social care settings. The result is a complex set of programmes using both PCR and rapid tests. But care providers have experienced delays in receiving test results, there were delays in implementing testing policies, and funding for rapid testing in the sector was extended late.

Capacity and access

National capacity for antigen testing – used to determine if someone currently has the virus – has increased considerably since the start of the pandemic. Testing introduced in social care around the peak of the first wave – for people with symptoms, those moving into care homes from hospitals or the community, and in settings with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 outbreaks – has continued. And greater testing capacity enabled government to introduce and extend new testing programmes in social care (for example, see sections on whole care home and regular testing programmes below). In addition to PCR tests carried out in laboratories, ‘rapid’ lateral flow tests (LFDs) were introduced in December 2020. The reported number of tests conducted among care home staff in England increased significantly between September 2020 and early 2021.

Yet some problems with testing in social care have persisted. Government promised ‘to get all tests turned around in 24 hours’ by the end of June 2020. But national testing capacity was put under considerable strain in September, following – in the Prime Minister’s words – a ‘colossal spike’ in demand. In August and September, social care leaders reported delays in obtaining testing kits and slow turnaround times for results, partly due to laboratory capacity.,,, In response to these problems – and as COVID-19 rates were increasing again in care homes – a new process was introduced to prioritise care home tests in laboratories. Government also said that it would prioritise allocating tests for certain groups., NHS patients, care homes and NHS staff made up the top three priority groups for COVID-19 testing and – according to the Dido Harding, head of NHS Test and Trace – together accounted for around half of the total testing capacity in mid-September.

Despite action to improve testing turnaround times, there is some evidence that social care providers continued to experience delays in receiving test results into October., In November, Dido Harding told a select committee hearing that 58% of care home test results had been returned within 48 hours the week before, describing this as ‘the best we have done for some considerable time’. But as demand for tests increased in December, turnaround times again increased nationally – including at satellite testing centres, which are predominantly used by care homes – before improving in January and February 2021., As of 26 January 2021, 58.1% of care home test results were returned within 48 hours.

‘Whole care home’ testing

At the start of June, government announced it had met its target to ‘offer’ whole care home testing – where all residents and staff within a home are tested, whether symptomatic or not – to every care home for those aged 65 and older (older adult care homes). But survey data from National Care Forum suggest that not all staff and residents in care homes were actually tested by this date. The programme was expanded to all care homes from 7 June. Those in supported living, extra care housing, and receiving care at home were not eligible. In July, government said that details were being ‘worked through’ to offer an initial round to extra care and supported living settings ‘at most clinical risk’, but a survey of providers in October reported that only a small proportion of these services were accessing the scheme.

Regular testing

The start of regular testing in care homes was announced in July, ahead of the NHS (where repeat rapid testing for NHS staff was introduced nationwide in mid-November). This involved weekly PCR tests for staff and monthly tests for residents, initially prioritising care homes for older people and those with dementia. The programme was due to reach all care homes that registered by the end of the month, but quickly ran into problems. The Department of Health and Social Care cited ‘rising demand’, ‘unexpected delays’, and problems with the test kits used, and pushed back the date for reaching all older adult care homes to 7 September. But in mid-September, the chief executive of Care England said that there were still ‘delays […] and problems with the labs getting the results back in time. It seems that the government makes an announcement first and then scrabbles around to see how it makes it happen’.

Other care homes could start placing orders for test kits from the 31 August, and there were calls from social care leaders for wider groups to have access. The scheme was gradually expanded – utilising rapid tests in addition to PCR tests from December – to include:

- home care workers in domiciliary care organisations registered with the CQC (in November 2020)

- eligible extra care and supported living settings (in December 2020 and further expanded in February 2021)

- CQC inspectors (in December 2020)

- additional rapid testing twice a week for care home staff (or daily in the event of a positive case) supported by the rapid testing fund (in December 2020)

- eligible personal assistants (in February 2021)

- eligible adult day care centre workers (in February 2021)

- essential caregivers for care home residents with the highest needs and nominated visitors for all adult care home residents (in March 2021)

But several of these testing expansions happened later or were implemented in a less ‘regular’ way than initially set out in the government’s COVID-19 winter plan in November. For example, residents in care homes and ‘high risk’ extra care and supported living settings are tested monthly not weekly, and twice-weekly testing of staff in high risk extra care and supported living was not introduced until the end of February 2021 (rather than December 2020). The frequency of regular testing under these policies may have also been insufficient. Recent modelling suggests that frequent testing of care home staff – ideally including daily LFDs – is likely to be among the most effective strategies in preventing importation of COVID-19 to care homes.

Funding

At the end of 2020, government announced £149m of local authority funding to support rapid testing in care homes, including for staff, visiting professionals, and visitors., This was due to run until 31 March 2021. On 18 March – less than 2 weeks before the end of the funding period – government announced a further £138.7m for rapid testing in social care.

Support for staff and unpaid carers

People providing social care have continued to do so under extremely demanding conditions, without the same recognition as NHS staff. Following the first wave of the pandemic, some national policies that protect social care workers improved, but additional support for those at higher risk from COVID-19 came slowly. Existing problems with employment terms and conditions affected financial support available for social care staff, and government action to increase staff capacity was slow. Support for family providing care was also delayed.

Support for social care staff

National policies that help protect social care staff from the impacts of COVID-19 have evolved since the first wave. Over winter 2020/21, staff appeared to have better access to testing (see section on testing) and PPE (see section on infection prevention and control). And social care staff were prioritised for COVID-19 vaccines, alongside those working in the NHS – though there were some challenges reaching them (see section on COVID-19 vaccines). Not all staff benefited at the same time. Policy in these areas often prioritised staff in older adult care homes before being extended to others, such as those working in supported living services for people with disabilities or personal assistants.

Targeted support for more vulnerable staff has been slow and limited. Some people face higher risks from COVID-19, including men, older people, and minority ethnic people. In June, the Department of Health and Social Care published a risk reduction framework to help employers consider how they can support staff most vulnerable to COVID-19, and asked providers to carry out staff risk assessments ‘in response to […] concerns’ that vulnerable staff may not be adequately supported. NHS England had requested staff risk assessments for NHS agencies in April. In September, the government’s social care taskforce reported concerns among ethnic minority staff about this delay and providers’ implementation of risk assessments. The social care winter plan recognised the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on ethnic minority staff but provided no further support.

Poor employment conditions in social care have continued to affect support for the workforce during the pandemic. Unlike NHS staff, social care workers are not guaranteed sick pay above the statutory requirement, and the prevalence of low wages and zero-hours contracts mean incomes are precarious. The prospect of losing earnings is likely to be a barrier to getting tested and self-isolating if positive for COVID-19.,, A national study in June 2020 found lower levels of infection among residents in care homes where staff received sick pay., In September, government extended funding for infection control in social care (introduced in May 2020), which in part aimed to enable care providers to pay staff while self-isolating (see section on infection prevention and control). Some providers have reported that this funding was insufficient., During winter 2020/21, around 84% of care home providers paid full wages to workers who had to self-isolate (data available from 15 December 2020 onwards). A minority of care home workers received less than their normal pay (around 3%), Statutory Sick Pay only (around 12%) or no pay at all (around 1%) while self-isolating. Rates varied between regions and there are no data available for staff in other care settings.

National leadership for social care received a limited boost in the government’s social care winter plan, which announced a new post of Chief Nurse for Adult Social Care. In December, Professor Deborah Sturdy took up the role to ‘represent social care nurses and provide clinical leadership to the workforce’ as a 6-month secondment. The plan also included action for national and local government to review and improve wellbeing services. No substantial changes to the government’s wellbeing offer for social care staff followed this.

Workforce capacity

The social care workforce has been under major strain throughout the pandemic. The percentage of staff days lost in social care due to sickness rose from approximately 3% before the pandemic to 6% in February 2021 (including days lost for shielding and self-isolation).

Government was slow to act to help increase workforce capacity as the pandemic continued. In September 2020, the taskforce recommended that the Department of Health and Social care develop a short-term, social care workforce plan (within 6 weeks), focusing on retention, training and any impact on recruitment of the post-Brexit immigration system in the new year. It is unclear what action was initially taken. By January 2021, ADASS called for urgent government funding to help cover extra staffing costs, describing ‘alarming gaps’ due to staff ‘infection, self-isolation and sheer fatigue’. 3 days later, government announced a £120m ‘Workforce Capacity Fund’ for social care – a ringfenced grant for local authority spending on extra staffing incurred by 31 March 2021. Guidance on the grant also included ‘best practice’ examples of local authority initiatives to increase workforce capacity.

The government’s national recruitment campaign for social care staff – announced in April 2020 – paused after the first wave. The Department of Health and Social Care began a second round of television, digital, and radio advertising for the recruitment campaign in February 2021, alongside a new ‘Call to Care’ initiative. The initiative aimed to encourage people (including those on furlough) to take up short-term work in social care.

Unlike for the NHS, there are limited timely data on recruitment into social care. There is still no public information about progress against the government’s April 2020 target of recruiting an extra 20,000 staff. Skills for Care estimate that the vacancy rate across social care was 7% in February 2021, compared with around 6.5% in May 2020 and 8% before the pandemic.

Support for unpaid carers

Additional government support for unpaid carers came late in the pandemic. In the first wave, support and respite services that enable unpaid carers to take breaks from caring often closed, but government provided minimal support to reopen them. Many carers surveyed in September 2020 reported that support services had not reopened and 64% said that they had not taken a break during the pandemic. The social care taskforce recommended that the Department of Health and Social Care consider increasing its ‘respite offer’ for carers. From October, government enabled care providers to use funding for infection control to help reopen services. In late December, guidance exempted carer breaks from restrictions on gathering and the need to stay at home (no such exemptions were in place in the first wave).

Limited support for carers introduced during the first wave continued. In November 2020, policy changes to allow people to continue receiving their Carer’s Allowance when self-isolating were extended to May 2021. There have been some problems with delayed, unclear or outdated guidance for carers. For example, government first published tailored guidance for young carers and young adult carers in July 2020, over 2 months after it had been promised. Guidance for unpaid carers of adults with learning disabilities and autistic adults also failed to signpost when government introduced access to free PPE for some carers in January 2021 (see section on infection prevention and control). A September 2020 survey found half of carers responding wanted clearer and more specific government pandemic guidance.

Infection prevention and control

In the first wave of the pandemic, social care providers faced major shortages of PPE, and dedicated funding for measures to prevent and control infections in care homes was slow to arrive. Since then, policy on PPE has been less contentious and appears to have improved substantially – though there is some evidence that problems have not been entirely fixed, and a lack of clear data makes it hard to know whether care providers’ PPE needs are being met. Cliff edges for funding for infection control measures have created uncertainty for the sector.

PPE

National policy on PPE has evolved over time – starting with an emergency response to help get supplies to the front line, followed by a focus on improving data and procurement, and establishing domestic supply chains and distribution networks. In September, government’s social care winter plan committed to providing free PPE for care homes and domiciliary care providers until the end of March 2021, as well as PPE for local agencies to distribute to other providers not eligible for the government’s PPE portal (such as personal assistants). This scheme was later extended to June 2021, then to March 2022. Eligibility has also been expanded: the offer of free PPE was extended to all ‘extra-resident carers’ – unpaid carers who do not live with the person they provide care for – at the end of January 2021.

There is some evidence that problems with access to PPE continued into autumn 2020. In November 2020, Jane Townson, Chief Executive of the UK Homecare Association, told two parliamentary select committees that providers were still ‘unable to access the quantities that we are told they should be able to order through the portal because there are not enough supplies behind the scenes’. She said that, despite government talking about ‘free PPE’, PPE remained a major additional cost for providers. Surveys by the National Care Forum in October and November suggest government supplies did not meet provider needs.,

A lack of clear publicly available data makes it hard to assess how well the sector’s PPE needs were met over time. But, overall, supply of PPE to care providers appears to have improved after the first wave and into 2021. CQC survey data suggest that PPE access for home care providers improved considerably between early May and late June 2020., Around 85–95% of home care providers in England reported having enough PPE to last more than a week between September 2020 and January 2021 (with London reporting lower availability than other areas). ,,, This compares with around 70–75% in May 2020.

Funding for infection control

A dedicated fund to help tackle the spread of COVID-19 in care homes and other care settings – the infection control fund – was introduced by government in May 2020. The fund was intended to cover a range of infection control measures and the staffing costs needed to implement them. Key aims of the funding included helping care providers to reduce movement of staff between care settings or paying wages of self-isolating staff.

In September 2020, government extended the infection control fund to the end of March 2021, with an additional £546m of ringfenced funding and revised conditions for spending it. The funding came in two parts: 80% for care homes and community providers regulated by CQC based on the number of beds and care users in each area; and 20% allocated by local authorities at their discretion to support the ‘full range’ of providers to tackle infections. Unlike the first round of infection control funding introduced in May 2020, more of the funding could be used to support social care settings in the community outside care homes.

National care provider bodies welcomed the extended funding but noted it was less generous than the first round, and unlikely to cover all additional costs., Care leaders also described the administrative burden of accessing the funding., On 18 March 2021 – less than 2 weeks before the funding was due to end – government announced a further £202.5m for infection prevention and control in social care (and combined this with funding for testing into an infection control and testing fund)., Funding was also provided through the NHS to help establish safe accommodation for people being discharged from hospital to a care home with a positive COVID-19 test or a pending test result (see section on interaction between social care and the NHS).

Staff movement

Over the course of the pandemic, government changed its position on how to mitigate the impact of staff moving between different care settings on COVID-19 transmission in care homes. Government funding for infection control introduced in the first wave included support to help providers ensure ‘in so far as possible, that members of staff work in only one care home’. In September, in response to a national study showing higher levels of infection in care homes with staff who worked across multiple sites, the social care taskforce advised further measures to avoid staff moving between settings. On the same day, government’s social care winter plan told providers to ‘limit all staff movement between settings unless absolutely necessary’, and extended existing funding for infection control.

Despite the taskforce citing concerns about the potential impact of introducing legislation banning staff movement between settings on staffing capacity, the social care winter plan stated that regulations would be used to enforce restrictions. On 13 November, government launched a consultation on proposals to legally require care home providers to restrict staff movement ‘in all but limited circumstances’ – saying that it planned to introduce legislation ‘by the end of the year’. Responses to the consultation raised concerns about the proposals, including that staff wellbeing and capacity would be negatively impacted, the infection control fund would not cover costs, and that there was limited consideration of the impact on people with learning disabilities and autism in care homes.,,, Government ultimately did not introduce legislation on care home staff movement (though guidance for care home providers on restricting movement was published in March 2021). Available data suggest that some staff movement continued during winter 2020/21 but around 78% of care home providers had no staff working between services. There are no published data on staff movement before 15 December, so we do not know how it has changed over the course of the pandemic.

Guidance

Government published new and updated guidance on infection prevention and control throughout the latter half of 2020 and into 2021. For example, guidance on the admission and care of residents in a care homes during COVID-19 was updated 11 times between June and the end of December 2020. Guidance on PPE, and hospital discharge (see section on interaction between social care and the NHS) has also been updated several times. The first guidance on visiting care homes was published in July and remains a contentious policy area that has been subject to several changes (see Box 2).

Keeping track of and implementing complex and changing guidance has not always been easy. ,,, CQC found that some providers felt confused by the high volume of guidance on COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic. Analysis of data from CQC care home inspections carried out in August 2020 found that some providers had outdated infection prevention and control policies. At the same time, guidance in some policy areas has been slow or limited. For example, initial guidance for supported living services was withdrawn in May 2020 and government did not publish new guidance for this part of the social care sector until August 2020. By March 2021, there was still no specific guidance for day services.

Box 2: Guidance on visiting care homes during the pandemic

Having family and friends visit is a normal part of life for many care home residents. The pandemic has made this challenging and policy on visiting has been contentious.

In the first wave, there was no specific guidance on stopping or enabling care home visits. But many providers pre-emptively restricted visits to care homes in March 2020 and wider COVID-19 guidance for care homes advised against visits in April.

The first government guidance on visits to care homes was published on 22 July 2020. It said that care homes could develop policies for ‘limited visits’ but should seek alternatives wherever possible. Some providers or councils closed care home doors despite this.,

The initial guidance on visiting was subject to various updates – often reflecting changes to local tiered arrangements and national COVID-19 restrictions. In November, the guidance set out options to maintain visits outdoors or with screens. Following pilots in mid-November, rapid testing to help enable visits to care homes was introduced at the start of December. But changes in late December meant a return to outdoor or ‘screened’ visits for care homes in new Tier 4 areas. This policy was extended to all care homes when the third national lockdown began in January 2021., Restrictions eased from 8 March to allow one named visitor per resident, enabled by testing (later expanded to up to three regular visitors).

The guidance consistently allowed visits to care homes in ‘exceptional circumstances such as end of life’, though this was not defined until December 2020. But available data suggest nearly 2/5 of care homes did not allow visits (even in exceptional circumstances) during January and February 2021. This decreased during March and April (to 11% in the week ending 26 April). There is considerable regional variation in the proportion of care homes accommodating visitors.

Balancing the risks and benefits of visiting in care homes is complex. Social care leaders have raised concerns about the profound impact of visiting restrictions and isolation on the wellbeing of care home residents., The guidance in July 2020 was subject to a legal challenge, and sector leaders criticised subsequent changes as overly restrictive and ‘unlikely to be useable’ by people with dementia or sensory loss. SAGE’s assessment in October 2020 was that prohibiting care home visits had a ‘substantial social and emotional impact on residents’ and low impact on transmission, deaths and severe infections – but added that ‘if infection does get into care homes the impact can be devastating’.

COVID-19 vaccines

The COVID-19 vaccination programme has been central to the government’s pandemic response and a broad success so far. A vaccine taskforce was established by government in April 2020 and the first vaccine was approved on 2 December 2020. Many people receiving social care were prioritised by government and vaccinated quickly, though it is harder to get a picture of vaccination coverage among people receiving care outside older adult care homes. Vaccinating social care staff has proved more difficult, despite efforts by policymakers to address challenges.

Vaccine prioritisation

Decisions about who receives COVID-19 vaccines when and in what order are complex. Government decided priority groups for vaccinations (and set targets for reaching them) chiefly according to people’s risk of dying from COVID-19. Its decisions have been based on advice from the JCVI – an independent body of experts.

JCVI published advice on the initial nine priority groups for the COVID-19 vaccination programme on 2 December 2020, and updated this advice on 30 December. As Table 2 shows, many people who receive and provide social care were prioritised in these groups.

JCVI’s advice on these priority groups changed over time, which affected eligibility in social care. A key change was advice regarding people with learning disabilities. Younger adults most commonly access social care support because of learning disabilities, which bring a higher risk from COVID-19. JCVI initially only included people with severe and profound learning disabilities in group 6. Some clinical commissioning groups went beyond this advice to include people with mild and moderate learning disabilities. On 23 February 2021, government accepted a new JCVI recommendation to add everyone on the GP learning disability register to group 6.

Table 2: People who receive and provide social care included in JCVI vaccine priority groups, and government vaccination targets,,,***

|

Priority group |

JCVI category (advised on 30 December 2020) |

Government estimate of number of people in England (19 January 2021) |

People who receive and provide social care included in this group |

Government target for offering the first dose |

|

1 |

Residents in care homes for older adults |

300,000 |

Residents in care homes for older adults |

14 February 2021 (NHS England target of 31 January) |

|

Carers in care homes for older adults |

400,000 |

Staff directly providing care in care homes for older adults |

||

|

2 |

All those aged 80 and older |

2.8 million |

People in this age group receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

14 February 2021 |

|

Front-line health and social care workers |

3.2 million |

~1.1 million staff directly providing social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

||

|

3 |

All those aged 75–79 |

1.9 million |

People in this age group receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

|

|

4 |

All those aged 70–74 |

2.7 million |

People in this age group receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

|

|

Clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) individuals (aged 16–70) |

1 million |

People in this age group and identified as CEV by a GP or hospital clinician, receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people (Updated on 23 February to include people with Down’s syndrome) |

||

|

5 |

All those aged 65–69 |

2.4 million |

People in this age group and not identified as CEV, receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

15 April 2021 |

|

6 |

All those aged 16–64 and at higher risk due to underlying health conditions |

6.1 million |

People in this age group, not identified as CEV but in a clinical risk group receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people, including people with severe and profound learning disabilities (updated on 23 February to include people with mild and moderate learning disabilities) Unpaid adult carers of people in a clinical risk group (not included prior to 30 December) |

|

|

7 |

All those aged 60–64 |

1.5 million |

People in these age groups neither identified as CEV nor in a clinical risk group, receiving social care in settings other than care homes for older people |

|

|

8 |

All those aged 55–59 |

2 million |

||

|

9 |

All those aged 50–54 |

2.3 million |

Vaccinating residents in older adult care homes and other social care recipients

National NHS bodies have been responsible for the operational delivery of the vaccine programme in England. Vaccinations have been delivered in a range of settings, including GP practices, pharmacies, and by ‘roving’ vaccination teams visiting care homes.

For practical reasons, COVID-19 vaccinations did not start in older adult care homes first, despite them being prioritised by government policy. The first vaccine to be approved in the UK – the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine – is less suitable for delivery in care homes, including because it must be stored at ultra-low temperatures. So vaccinations of care home staff and people older than 80 began in hospitals on 8 December, before the first vaccinations in care homes on 21 December., The Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine was approved on 30 December and prioritised for use in care homes, since it is easier to store and transport.

The continuing spread of the virus caused some challenges. In mid-January, NHS England described ‘some uncertainty’ among primary care providers about vaccinating care homes with active outbreaks, despite previous guidance to proceed following risk assessments. Despite this, older adult care homes received vaccines quickly. On 1 February 2021, the NHS announced it had offered first doses of the COVID-19 vaccine to all residents in older adult care homes; severe outbreaks only prevented vaccinations in ‘a small number of cases’.

People in other care settings, including younger adult care homes, are not in a specific JCVI priority group. But many of those included in groups 2–4 were likely vaccinated quickly – approximately 91% of all those aged 70 and older and 82% of all CEV people received their first dose by 14 February.

Vaccinating social care workers

Vaccinating social care staff has proved more difficult. Government announced it had met its target to offer the vaccine to the top four priority groups by 14 February. In fact, only 69% of staff in older adult care homes received their first vaccine dose by this date, compared with 95% of residents. Outside older adult care homes, only half of social care staff were vaccinated by 21 February, compared with 91% of front-line NHS trust health care staff.

Progress with vaccinations continues, but it has taken longer to vaccinate social care staff than the people they care for and NHS workers. There are several possible reasons for this. Lack of oversight and fragmentation of the social care workforce has hampered progress to identify, vaccinate, and to monitor uptake among staff. Unlike for NHS staff, there is no national register of most front-line social care workers, who are employed by thousands of providers. Local authorities (responsible for identifying care workers for vaccination) did not have relationships with all social care employers, particularly individuals employing carers through direct payments. And it appears to have been harder to identify live-in care staff because they often work in different local authority areas to their employers.

In the general population, people from ethnic minority communities and people in deprived areas are more likely to be hesitant about receiving the vaccine. This may affect vaccine take up among the social care workforce, which is more ethnically diverse than the general population and low paid. Generally, barriers to vaccination include low confidence in the vaccine, distrust, inconvenience and poor access.

National leaders have attempted to increase uptake among social care staff. In January, the Department of Health and Social Care updated guidance on infection control funding (see section on infection prevention and control) so that care providers could use it to pay staff when being vaccinated, or to cover their travel costs for attending vaccinations. In February, government took steps to improve national monitoring of vaccinations among social care staff, making changes to their data collection processes and encouraging local authorities to improve information recording. Social care workers were also offered the option of self-referral for vaccination – initially between 11 and 28 February (this option was later removed but reinstated in April)., Harder incentives have also been considered. Some social care providers introduced policies to only recruit staff who receive the COVID-19 vaccine. In April, government announced a consultation on legally requiring social care staff to be vaccinated.

Interaction between social care and the NHS

In the first wave of the pandemic, among the most controversial policy decisions included discharging patients from hospitals to care homes without COVID-19 testing., Improving interactions between the NHS and social care has received greater policy attention since then – including schemes to improve hospital discharges and boost NHS support to care homes. But publicly available data or robust evaluation to assess the implementation and impact of these policies are lacking. And late extensions to funding and indemnity cover for social care settings receiving patients with positive COVID-19 tests created considerable uncertainty.

‘Discharge to assess’

Early in the first wave, NHS bodies asked hospitals to urgently discharge patients who were ‘medically fit to leave’, including into social care. NHS Continuing Healthcare processes (where some people with health needs can qualify for social care to be paid for by the NHS) were postponed, and the NHS received £1.3bn to support discharge processes. In mid-April 2020, government introduced testing prior to discharge from hospital into a care home, and local authorities were made responsible for arranging accommodation for people discharged into social care where providers were unable to safely isolate them.

A new hospital discharge policy was announced by government in August 2020. From September 2020 to the end of March 2021, government provided £588m (via the NHS) to implement the discharge to assess model, which involves providing and paying for services to help people leave hospital before their care and support needs have been assessed. The funding helped cover the cost of care homes, community nursing services, and care in people’s homes for up to 6 weeks following discharge from hospital. The funding also covered urgent care in the community to prevent someone being admitted to hospital.

At the same time, NHS Continuing Healthcare processes restarted. This resulted in two types of work for local services. First, any referrals, reviews, and assessments previously deferred due to COVID-19 needed to be carried out. This meant assessing anyone who received free care (from the additional COVID-19 funding) between March and August 2020 and – depending on their eligibility – transferring them on to one of the usual funding streams (which might mean their care being paid for by the NHS, local authorities, or individuals). Second, NHS Continuing Healthcare assessments for people discharged after 1 September 2020 were reinstated and now needed to be confirmed within 6 weeks following discharge.

‘Designated settings’ and indemnity insurance

A new designated settings scheme was also announced in September 2020, which aimed to provide care in a residential setting for people discharged from hospital with a positive COVID-19 test or a pending test result.,, To make the scheme work, local authorities were asked to identify suitable settings in their area and notify CQC of facilities ready for inspection against the latest infection prevention and control standards.

Implementation of the scheme has been mixed. CQC data show that by 15 December 2020, there were 118 CQC-assured settings within 93 local authorities in England (and a further 31 ‘alternative settings’ using NHS facilities for the same purpose). By 4 February 2021, this had increased to 156 CQC-assured settings within 109 local authorities (and 40 alternative settings). The main reasons that suggested locations failed the assurance process were that they were unsuitable, not ready, or had no team. Lack of data makes it difficult to assess the comprehensiveness and impacts of the scheme. But it seems unlikely that government met its aim to have at least one setting per local authority by the end of October. CQC analysis showed wide variation between areas in the number of designated settings available. Some regions experienced comparatively high hospital bed occupancy and low designated setting bed capacity in early 2021, when COVID-19 incidents in care homes peaked for the second time.

One factor holding back the expansion of the scheme was challenges for social care providers obtaining indemnity insurance., In mid-January, government announced that a ‘targeted and time-limited indemnity offer’ for designated settings would be introduced, available until the end of March 2021., This was welcomed by the sector, though concerns were raised about the temporary nature of the cover and some questioned whether it would be enough to encourage providers to sign up.,, Others called for government to extend the arrangements to the rest of the sector, putting social care on a par with the NHS.,

Both the designated settings scheme and indemnity cover were to be paid for from the £588m funding due to run until the end of March 2021. In February, leaders were told to ‘assume that individuals discharged from hospital from 1 April 2021 onwards who require care and support under a discharge to assess scheme will need to be funded from locally agreed funding arrangements’. Then, on 18 March 2021, government announced an extra £594m of additional discharge funding – less than a fortnight before the funding was due to end and the day after a joint statement from social care sector leaders calling for an immediate extension of emergency funding measures. On 25 March 2021, the indemnity offer was extended to the end of June 2021, less than a week before it was due to finish. No robust evaluations have been published of these various hospital discharge arrangements.

Enhanced health care in care homes

The NHS long term plan in 2019 included a commitment to provide ‘enhanced health care in care homes’ by 2024, as part of an ambition to provide more proactive services to people using social care. The service – provided by primary care networks – includes a weekly ‘home round’ for residents and support from a multidisciplinary team. Some elements of the service started in May 2020 and the full service was implemented in October 2020.

There is limited evidence to understand how the service has been implemented or its impact. Evaluation of an early version of the enhanced support in care homes initiative in Wakefield between 2016 and 2017 found some positive results, including fewer potentially avoidable hospital admissions among care home residents receiving the service than the matched control group. But the evaluation found no significant difference in overall hospital admissions or A&E attendances. This is, however, unlikely to tell us much about the short-term impacts of the service introduced during the pandemic. Developing complex interventions is challenging and potential benefits take time to be realised. Relationships between the NHS and social care during the pandemic have varied widely between areas.

Oversight of adult social care

A range of legal and regulatory changes were introduced in response to the first wave of the pandemic – including suspending routine quality inspections and emergency powers introduced through the Coronavirus Act 2020. From June 2020, local authorities stopped using ‘easements’ to the Care Act 2014 to prioritise services, but concerns about their use remained. There was also widespread concern about inappropriate use of ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR) orders. Since the first wave, the CQC has taken a flexible approach to regulating the sector in response to changing risks posed by COVID-19.

Care Act easements

In March 2020, the Coronavirus Act 2020 introduced temporary relaxation, or ‘easements’, of some local authority responsibilities related to social care. The easements enabled local authorities to ‘streamline’ assessments of people’s care needs and eligibility for publicly funded support, and charge for care retrospectively. Under the most extreme circumstances, local authorities would not need to carry out detailed assessments of people’s care needs, and only needed to meet people’s needs if not doing so would breach their human rights.

The Coronavirus Act, including the Care Act easements, was extended in September 2020. In practice, the easements to the Care Act were formally used relatively rarely. Eight out of 151 local authorities with social care responsibilities used them – none after 29 June 2020. On 22 March 2021, the easements were removed from the Coronavirus Act.

Understanding the impact of the easements is difficult. ADASS engaged with eight councils using the easements during spring 2020 and found that most of these councils moved to virtual assessments and reduced the length of time for assessments, postponed scheduled reviews, and redeployed staff from reviewing teams to other areas where need was deemed to be greater. But it found variation in how the easements were used and that no council had used all of them. Think Local Act Personal – a government-funded partnership of health and care organisations – described ‘a very grey line’ between councils that implemented the easements and those that did not. The government concluded that there were insufficient data to assess the effect on people accessing social care, but that ‘chief social workers are content that the Care Act easements have been used appropriately’.

Do not attempt resuscitation orders

DNACPR orders are used to protect some people from the use of CPR when they do not want it, it is not thought it will work, or the harm outweighs potential benefits. Throughout the pandemic, there have been fears about the use and impact of policies to ration care for some population groups,,, – including inappropriate or blanket use of DNACPR orders on people with learning disabilities and older people. Several times during the first phase of the policy response, NHS England issued guidance to clinicians to only use DNACPR decisions on an individual basis, and in consultation with the person receiving care or their family.

In response to these concerns, government commissioned the CQC to review DNACPR decisions made during the pandemic in October 2020. The review found ‘a worrying picture of poor involvement, poor record keeping, and a lack of oversight and scrutiny of the decisions being made’. According to the CQC’s review, 119 (6%) of the 2,048 social care providers responding to the CQC’s information request ‘felt that people in their care had been subject to blanket DNACPR decisions’ at any time since 17 March 2020. The CQC concluded they ‘cannot be assured that decisions were, and are, being made on an individual basis, and in line with the person’s wishes and human rights’.

National regulation and oversight

The CQC has adapted how it regulates care services in response to COVID-19. During the first wave, the CQC suspended routine quality inspections, except where there were concerns of harm, and used a new ‘Emergency Support Framework’ for conversations between inspectors and providers. This was designed to help the CQC monitor risks and understand the impacts of COVID-19. In June, the CQC confirmed it would adapt the framework to support a ‘managed return to routine inspection of lower risk services in the autumn’.

Over the summer, CQC introduced provider collaboration reviews and infection prevention and control inspections, which included inspecting services where there were no concerns of harm. Provider collaboration reviews aimed to assess how health and care services collaborated during the pandemic to provide care for older people. Reviews in 11 areas in July and August 2020 found ‘wide variation in collaborative working’ and concern that adult social care was not sufficiently involved in local system working, and that many social care providers felt ‘overwhelmed and isolated’. Infection prevention and control inspections focused on a mix of care homes identified as examples of good practice in infection prevention and control, and 139 risk-based inspections. In 65% of care homes, inspectors were assured across all eight infection prevention and control policy areas considered. Inspectors were least assured that staff were using PPE effectively and that care homes had up-to-date infection prevention and control policies (see section on infection prevention and control).

In October, the CQC announced a new ‘transitional regulatory approach’ of targeted monitoring and inspection in adult social care. This involved monitoring services using information from the Emergency Support Framework, provider collaboration reviews, and other sources, only using on-site inspections where necessary. As pressure on services increased again in January 2021, CQC confirmed it would only inspect services in response to ‘significant risk of harm’ or as part of the pandemic response – for example, to inspect potential designated sites for people discharged from hospital into residential care or monitoring DNACPR decisions. Provider collaboration reviews were paused until March.

The Department of Health and Social Care also increased its focus on social care in response to COVID-19. It reintroduced a director-general with sole responsibility for social care in June 2020, increased the size of its policy team by ‘around threefold’ (between April 2020 and January 2021), and carried out a review of risks to local care services and providers to inform its social care winter plan. Despite this, the NAO recently concluded that the government’s accountability and oversight arrangements for the social care market ‘do not work’.

National data

Lack of data on social care has constrained the policy response. For example, Matt Keeling – a member of SAGE’s Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling – told the Science and Technology Committee in June 2020: ‘I remember asking at some point, probably late March, what we knew about care homes, and we did not even know how many people were in care homes at that point. We can only generate models from the data available.’

Data for policymakers have improved during the pandemic. From April 2020, government began asking all care home providers to complete the ‘capacity tracker’ to track bed numbers and other data (including on PPE, workforce, and COVID-19 cases), and CQC developed a ‘domiciliary care tracker’ to collect data on home care., As the pandemic continued, these and other data were incorporated into a COVID-19 ‘Adult Social Care Dashboard’. In September, the government’s social care winter plan said the dashboard would be published ‘over the coming months’, so that the data could be viewed ‘in real time at national, regional and local levels’. Access to some emergency COVID-19 funding for social care – including the infection control fund and rapid testing fund – was contingent on weekly completion of information by providers. Government has said that the response rate for the capacity tracker ‘improved significantly’ after the introduction of the infection control fund.

Extracts from the CQC survey of home care providers were published without the raw data in their monthly COVID-19 Insight reports until January 2021. Some data from the capacity tracker were published in May 2021. Care providers had previously reported that they did not have access to key data from the capacity tracker, despite the effort and cost of providing it.

§ Major non-social care related events and policies are also included in italics.

¶ Government also published a separate COVID-19 winter plan in November 2020, describing the broader policy approach to managing the pandemic over winter. We refer to both the social care winter plan and the government’s broader winter plan throughout the report. We try to make it clear which one we’re referring to.

** We focus on policies related to COVID-19 antigen testing in social care. We do not focus on policies related to COVID-19 antibody testing, which focuses on whether people have previously had the virus.

†† Government data show the highest number of PCR tests in care homes reported in the week ending 22 December 2020 – 518,609 tests – and the highest number of LFDs reported in the week ending 9 February 2021 – 551,317 tests. See Department of Health and Social Care. Adult social care in England, monthly statistics: May 2021. Gov.uk; 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/adult-social-care-in-england-monthly-statistics-may-2021).

‡‡ For recent modelling (not yet peer reviewed) see Rosello A et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks in English care homes: a modelling study. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 (doi: doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.17.21257315).

§§ Extracts from the CQC Domiciliary Care Agency Survey have been published in charts in CQC COVID-19 'insight' reports on an ad hoc basis. It is possible to understand from these extracts how availability of PPE among home care providers changed over time, but raw data for the period covered here are not publicly available.

¶¶ Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines require two doses at intervals for greatest protection. In this section, we focus on progress to deliver first doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

*** For example, care in people’s own homes, younger adult care homes and community care.

††† ‘Alternative settings’ are where local authorities have agreed with NHS organisations that an NHS setting will fulfil the role of a ‘designated setting’.

‡‡‡ The capacity tracker was developed and is managed by the NHS North of England Commissioning Support unit (NECS), in partnership with NHS England. It was initially launched in 2019 for care home providers to share data on capacity to support discharges from hospital. Source: NECS. Capacity tracker [webpage]. NECS; 2021 (https://www.necsu.nhs.uk/capacity-tracker/).

Impacts on social care

The pandemic has had a major and sustained impact on social care users and staff. In this section, we summarise the latest publicly available data on COVID-19 infections, deaths and other impacts on social care in England during the second half of 2020 and up until April 2021. Where possible, we describe how the impact of COVID-19 has changed over time.

Gaps in the data mean we only have an incomplete picture. For example, there are limited data on people who fund their own care, unpaid carers, unmet care needs, and other areas. Comparing impacts across different stages of the pandemic is also difficult. Changes in the way that care home outbreaks are reported, for instance, prevent meaningful comparisons of how many care homes and residents were affected by COVID-19 in the first and second waves. The number of people living in care homes has also decreased – estimates suggest occupancy fell by around 10% since the start of the pandemic – making it harder to understand the scale of the impact on the changing care home population. Nonetheless, the available data paint a grim picture of COVID-19’s impact on social care in England.

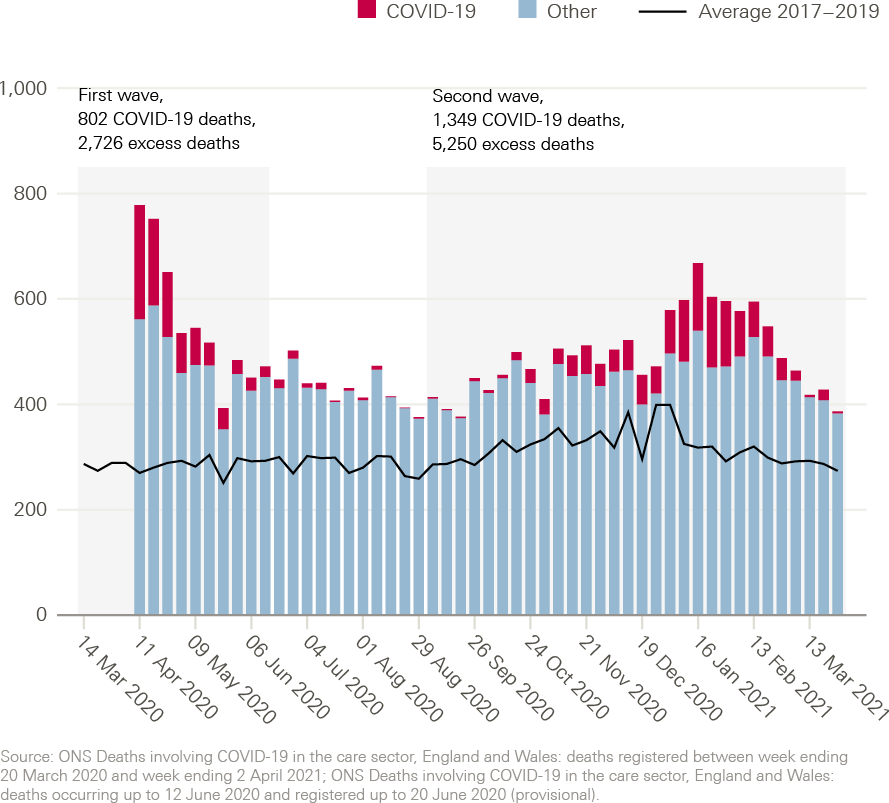

COVID-19 deaths and excess mortality among people receiving care at home

Significant increases in mortality have been reported for people receiving social care at home throughout the pandemic so far (Figure 2). Between 11 April and 19 June 2020, there were 2,726 excess deaths recorded among people receiving domiciliary care in England – a 96% increase compared with 2017–2019. Over the summer of 2020, in June and August, the number of deaths reported to the CQC continued to be higher than in previous years. Deaths then rose again from September 2020 onwards. During the second wave, between 5 September 2020 and 2 April 2021, there were 1,349 COVID-19-related deaths among home care users in England, and there were 5,250 excess deaths – a 55% increase compared with recent years.

These figures suggest that the pandemic has had a significant impact on home care users. But both the scale of the impact and the comparison with previous years need to be interpreted with caution. Providers registered with the CQC are not required to notify the CQC of all deaths, and – as the CQC only collects data on deaths from registered and regulated organisations – the data do not include people who receive support from individual self-employed carers. As a result, the available data will not capture all deaths among people who receive home care and are likely to be an underestimate of the true impact. The CQC has also stated that reporting varies greatly between providers, regions, and over time – and the UK Homecare Association has suggested that there may have been a rise in reporting during the pandemic.

Figure 2: Deaths of people receiving care at home in England, by week reported

COVID-19 outbreaks and deaths in care homes

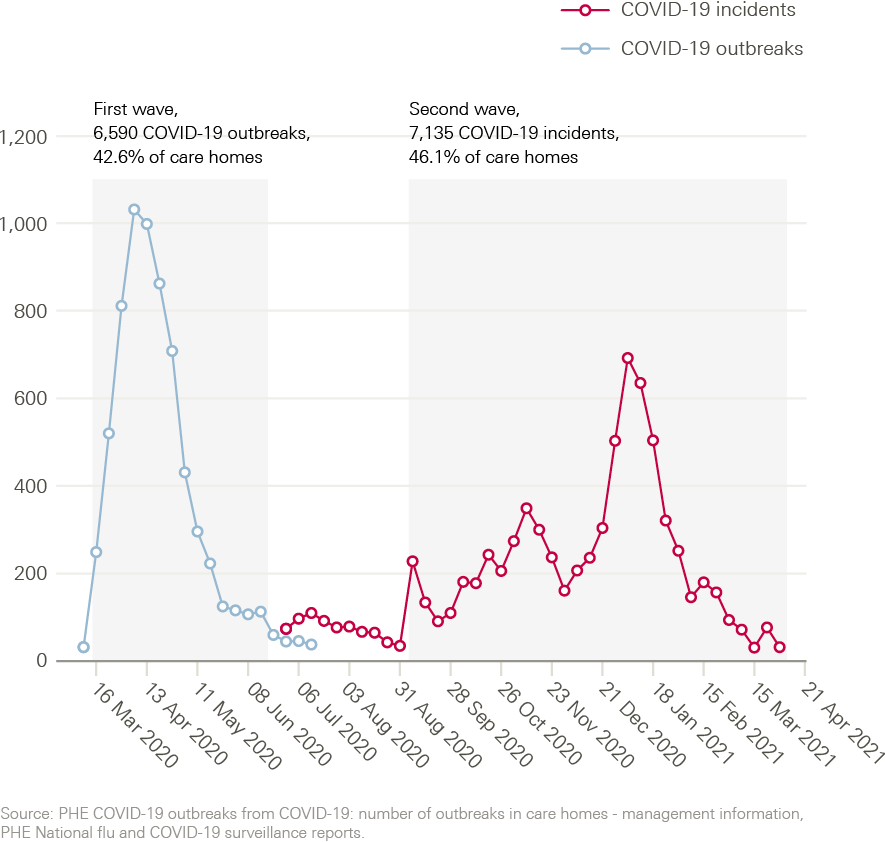

Care homes continued to be severely affected by COVID-19 beyond the end of the first wave in June 2020. Low numbers of COVID-19 outbreaks continued to occur in care homes between June and August, despite very low prevalence of COVID-19 in the community. As community prevalence increased from September 2020 onwards, the proportion of care homes that experienced COVID-19 outbreaks also rose. Between early September 2020 and early April 2021, 46% of care homes reported at least one confirmed case of COVID-19 (Figure 3) and there were 78,658 COVID-19 cases and 20,423 COVID-19-related deaths among care home residents (Figure 4). Throughout the pandemic, people with learning disabilities in residential care settings have been more likely to die with COVID-19 than others living in care homes.

The burden of mortality from COVID-19 has continued to fall disproportionately on care homes – albeit at a lower rate than during the first wave of the pandemic. Care home residents accounted for 26% of all COVID-19 deaths between 5 September 2020 and 2 April 2021. This compares with 40% of all COVID-19 deaths between 14 March and 19 June 2020.

Figure 3: Suspected and confirmed COVID-19 outbreaks and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 incidents in care homes in England, by week reported

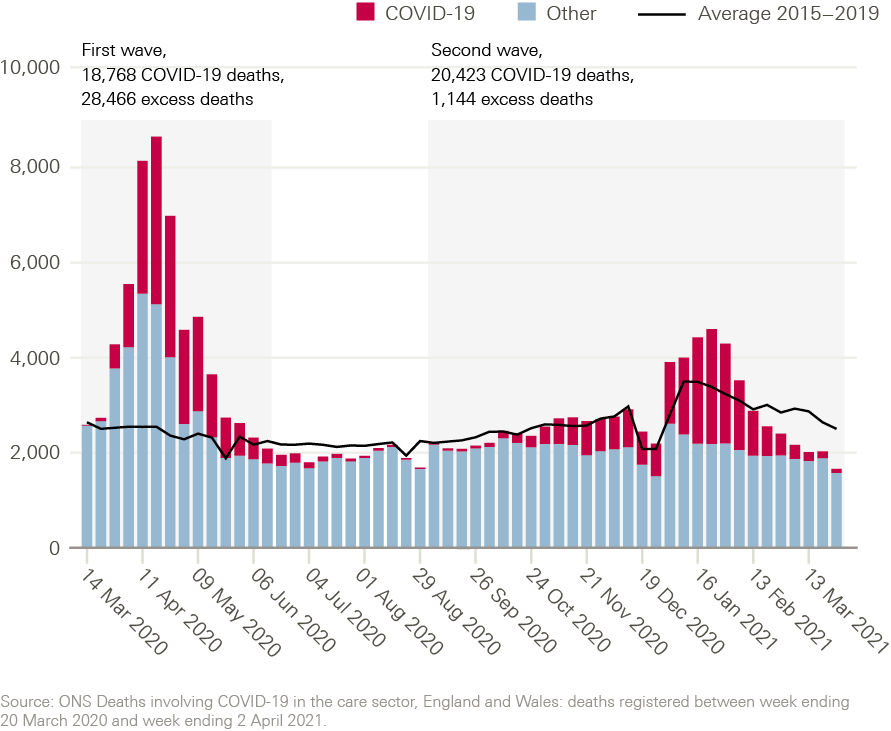

Excess mortality among care home residents

The level of excess mortality among care home residents has varied throughout the pandemic (Figure 4). During the first wave, excess mortality in care homes was significant – with 28,466 additional deaths compared with the 5-year average, equivalent to an 85% increase in mortality. But between June and September 2020, the total number of deaths among care home residents was below the average for 2015–2019. For deaths not related to COVID-19, this trend continued and remained below historical levels between October 2020 and April 2021. Both fewer deaths caused by flu infections and a decrease in the number of people who live in care homes could have contributed to this.

By the end of 2020, however, the picture worsened again. There was some excess mortality in care homes between late December 2020 and early February 2021, driven by the large number of deaths related to COVID-19 during the second wave of the pandemic. The fact that all excess deaths among care home residents between December 2020 and February 2021 were attributed to COVID-19 probably reflects improvements in access to COVID-19 testing, in contrast to the first wave when COVID-19 deaths were likely under-recorded.

Figure 4: Deaths of care home residents in England, by week reported

Early impact of care home vaccinations