Acknowledgements

The author would like to express my gratitude to those who gave up their time to talk to me as part of this work. Thanks also to Clare Allcock, Charlotte Williams and Katherine Checkland for providing thoughtful comments on early drafts of this report.

I would also like to thank colleagues at the Health Foundation for their support and guidance during the resesarch and production of this report, including Tim Gardner, Bryan Jones, Adam Steventon, Ruth Thorlby and Will Warburton.

Errors and omissions remain the responsibility of the author alone.

Executive summary

The new care models programme already appears at risk of becoming old news. Having first been signalled in 2014 in the Five year forward view, it is due to end in 2018. Plans for much larger place-based systems of care have developed in response to the squeeze on NHS finances and the growing complexity of health and care needs. The national spotlight is now firmly fixed on the creation of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) and accountable care systems (ACSs).

Yet those seeking to drive the development of STPs and ACSs, at all levels of the NHS, can benefit from valuable learning from the vanguard sites of the new care models programme. These sites have worked through the complexities of bringing together professions and organisations to develop place-based models of better coordinated care for people with complex health and social care needs.

Shining a light on what can be learned from new care models

While the design and technical aspects of the new care models have been discussed by others, this report seeks to shine more light on how the sites have made changes. Based on first-hand accounts from clinicians and managers who developed and implemented new care models, this report describes an approach to change that emphasises local co-creation and testing of care models as an alternative to the traditional top-down structural approach to change in the NHS.

The report identifies 10 lessons to support providers and commissioners seeking to adopt this new approach.

- Start by focusing on a specific population.

- Involve primary care from the start.

- Go where the energy is.

- Spend time developing shared understanding of challenges.

- Work through and thoroughly test assumptions about how activities will achieve results.

- Find ways to learn from others and assess suitability of interventions.

- Set up an ‘engine room’ for change.

- Distribute decision-making roles.

- Invest in workforce development at all levels.

- Test, evaluate and adapt for continuous improvement.

Implications for the future: local and national principles

The report identifies additional implications of the new care models programme for local health and social care leaders embarking on cross-organisational change. Taking time to understand and adapt to the local context is essential for new care models. Sites should focus on care redesign and its intended aims, and reserve time for people to collaborate to support co-design. Finally, evaluation must be seen as a core component of any plan, and teams must be given the time and support to collect and analyse data.

Finding this time can be difficult, as the actions of national policymakers and regulators often create multiple pressures and competing priorities that local leaders struggle to balance. By contrast, the national new care models programme consciously set out to create an enabling environment and headspace for professionals to make change happen. While this report focuses on what local leaders can do, it also identifies three key ways national bodies can support cross-organisational change.

- Support new and existing systems –further focus is needed on what the national performance and governance frameworks should look like – they must build in the time and headspace needed to carry out care redesign, allowing for experimentation and failure. This is important not just for the most advanced systems, but also for those at a more formative stage of developing new models.

- Send the right message – national messaging should focus on the core aims of system change and not simply on restructuring. It should encourage sites to answer the question: ‘how can care be improved for patients in this area?’ as opposed to ‘how can this area become a new care model?’

- Continue to build evaluation capability and capacity –investing in robust local and national evaluation will enable sites to understand if changes are improving care. This will make sure that what works and why is shared and that areas can learn from their mistakes.

History suggests that the acronyms linked to the new care models programme will soon fade from view. But wider application of the programme’s approach to supporting local change could have a substantial impact on the health of the population and, in particular, on the lives of people who fall through the gaps of service fragmentation.

Introduction

The new care models programme is a large-scale experiment by the NHS’s national bodies to develop ‘major new care models’ that can be replicated across England. Introduced by the NHS’s Five year forward view in 2014 and launched in 2015, it aims to break down the traditional barriers between health and care organisations to establish more personalised and coordinated health services for patients.

The programme aims to reconcile ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches to change management. To do this, 50 local vanguard sites were selected to develop new care models, supported by a national programme led by NHS England over 3 years.

‘[The NHS needed] to overcome the artificial dichotomy between change being led centrally or locally… This is not one size fits all, not 1,000 flowers blooming; it’s horses for courses.’

Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England

The national programme is due to end in March 2018. Responsibility for establishing new care models across the country is already shifting to sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) and accountable care systems (ACSs), which operate across larger geographies than the vanguards. The plan is that STPs and ACSs will continue to grow existing new care models and encourage the creation of new ones. NHS England is aiming for half of England to be covered by new care models by 2020/21.

Sharing learning from the new care models

As the focus moves to much larger place-based systems and expansion and coverage of the models, for some, it would seem that new models are already at risk of becoming old news. As focus shifts towards STPs and ACSs, valuable learning from the experience of those working within the vanguard sites may be lost.

In this report the Health Foundation has captured and shared some of this experience by focusing on how the sites made change happen in complex environments and between a diverse range of stakeholders.

By exploring what the leaders within vanguard sites thought, felt and did, and drawing on the literature of cross-organisational change, this report sets out 10 lessons that may help providers and commissioners to develop new models of care locally. It does not attempt to quantify how quickly or how much the new models changed outcomes – evaluations of the models are currently ongoing.

How was the learning captured?

This report gathers learning from the first 2 years of work across three of the five types of new care models – enhanced health in care homes (EHCHs), multispecialty community providers (MCPs) and primary and acute care systems (PACSs).,, Of the 50 vanguard sites, 29 were selected as one of these types of new care model in March 2015. It was too early in the development of the other two types of new care model – urgent and emergency care systems and acute care collaborations – to include them in the research, as they were selected in August and September 2015 respectively.

To inform this report, a scoping exercise was undertaken. This involved attending local and national new care model events, as well as analysing the documents produced by all 29 of the relevant vanguard sites.

Eight vanguards were then identified as case studies for this report, to provide a representative spread of the new care model types and geographies. 45 local, middle to senior clinical and non-clinical leaders and evaluators were interviewed across the eight sites.

To aid the analysis, key national policy documents from the last 10 years were reviewed, as was academic literature about cross-organisational change and improvement.

What are new care models and how did they come about?

What is the new care models programme?

New care models were first announced in NHS England’s Five year forward view in 2014. The aim of the subsequent new care models programme is to ‘support and stimulate’ cross-organisational change across local health and care systems in England to contribute to the triple aim of improved patient care, reduced cost and better population health. Rules prescribing the ‘what’ of change have been limited, and restricted to categories of new care models to help create future blueprints for other areas to learn from. The programme follows on from a range of national initiatives with similar aims (see Appendix 1).

To help sites become new models, the national programme provided modest funding. This was allocated annually, based on the sites’ requests and on the NHS England-led programme team’s confidence in their plans. Funding ranged from around £500,000 to £8m per vanguard site per year., The programme gave sites flexibility as to how they spent this money, with some stipulations that increased over the course of the programme.

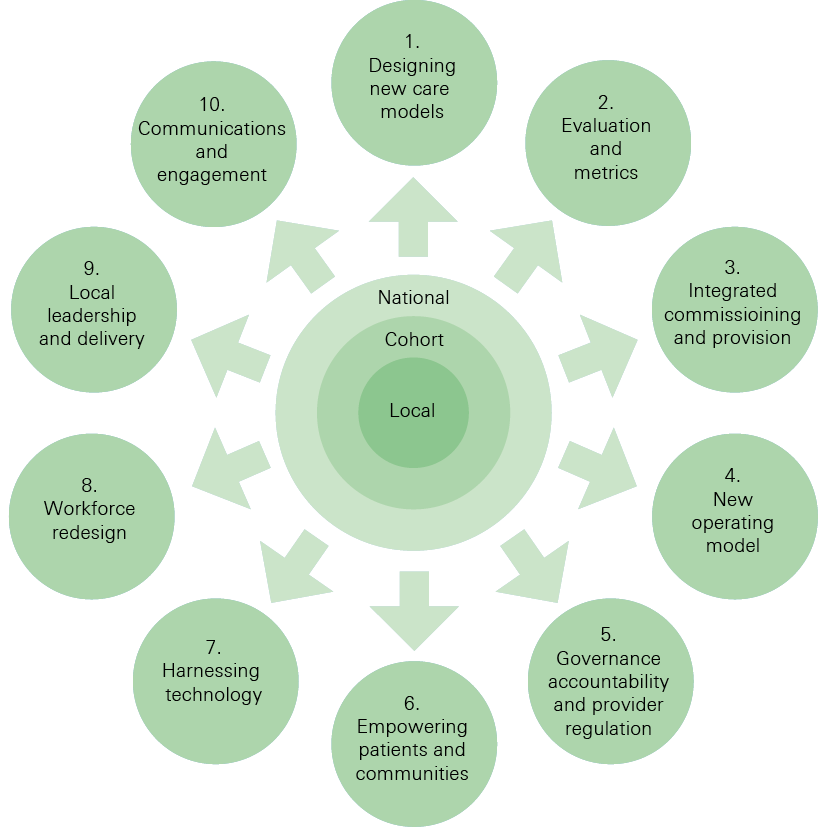

Through a national team, the programme also aimed to offer what the Health Foundation has described in a previous publication, Constructive comfort, as proactive support – support that focuses on enabling local systems to make the changes needed and gives them licence to test new ideas. The national support package of help and guidance covered 10 areas (see Figure 1), which were co-developed with the sites. Examples included communities of practice for the new care model types, access to workshops with expert advisors on specific areas of interest, and technical guidance on areas such as data interoperability.

Strong emphasis was placed on the design of the central programme on evaluation for local sites, to determine what works and how. , Sites were given funding to procure local quantitative and qualitative evaluations. They also had access to central evaluation support. This included deep-dive impact reports from the NHS England operational research and evaluation unit, as well as specialist analysis from the Improvement Analytics Unit – a relatively new partnership between NHS England and the Health Foundation that provides quantitative evaluation to show whether local change initiatives are improving care and efficiency.

Through this approach, the programme focused on learning how to make the new care models in the Five year forward view a reality. Some of this learning has since been distilled into published frameworks.,, These predominately describe the design of the care models and the technical aspects of change.

Figure 1: The 10 enablers from the national programme team

What do the new care models look like?

At its inception in January 2015, the new care models programme invited expressions of interest to become a vanguard from ‘areas and organisations that have already made good progress’. The programme assessed ‘good progress’ by looking at the positive characteristics of the applicants. These included:

- evidence of established relationships between providers and commissioners

- evidence of tangible progress in making changes across the health and care system

- a credible plan to make further change at pace.

Sites had three types of vanguard model to choose from. The three models aimed to improve care for similar populations: predominantly older people, those with chronic conditions and those identified as being at high risk of admission. The sites have, therefore, made service changes that reflect the needs of these targeted populations, with a focus on improving the provision of care outside hospitals.

This report identified the following common components in the new models.

- Improved care coordination and transitions – for example, integrated multidisciplinary teams in the community supporting patients with multiple conditions.

- More care in the community – for example, specialist clinics in primary care and the development of community pharmacy.

- Provision of crisis care and reductions in unnecessary hospital admissions – for example, rapid response and recovery services for those at risk of admission.

The size of registered populations varied across sites, as did the breadth of care redesign (Table 1). However, many of the models expanded beyond their initial parameters as the programme progressed. For example, some EHCHs developed plans for older people beyond care home residents, while some MCPs worked with acute providers. This suggests that the category of model pursued should not restrict options for future service changes and expansion.

What was the local context for the vanguard sites?

There is a wealth of literature on the importance of understanding local contexts when making change and improvement. But these contexts should not be regarded as restrictive backgrounds that predetermine how models develop. Sites should instead consider how context can be understood and broken down into individual components in a helpful way, and then altered if necessary.

There were some common but not universal factors in the social, organisational and historical context of the new care model sites at the time of their successful application to the programme. In the interviews carried out for this report, sites described the following features as supporting their local ambitions:

- stability in senior leadership positions across organisations

- a well-performing provider sector, based on national indicators

- a positive working relationship between providers and commissioners

- previous involvement with national initiatives focused on integration or primary care.

Sites did, however, also describe how these features had not always been present in their local systems and how the actions they had taken prior to the new care models programme had helped to create them. Many of the sites had started developing new models of care between 2 and 10 years before they became involved in the programme.

There were exceptions where these features were not present on application to the programme. All the sites also stressed they were subject to competing pressures, such as financial deficits and performance targets.

Table 1: Profiles of the three vanguard model types

|

Model |

Description |

Number of sites |

Who led the application? |

Scope of services |

Initial population |

Common services |

Population size |

|

EHCHs |

An option for areas seeking to integrate with social care services, and with a specific focus on connecting care homes into health care, to provide a dedicated offer for older people |

6 |

|

|

|

|

2,500–200,000 |

|

MCPs |

An integrated provider of out-of-hospital care |

14 |

|

|

|

|

100,000–300,000 (organised into localities of 30,000–50,000) |

|

PACSs |

Integrates the provision of hospital and mental health services – as well as primary community and potentially social care services |

9 |

|

|

|

|

250,000–300,000 (some organised into localities of 30,000–50,000) |

Note: Descriptions taken from NHS England expression of interest document.

Lessons to support the development and implementation of new care models locally

Cross-organisational and professional change in health and care systems is difficult. The vanguard sites had to make pragmatic decisions to help them make sense of complex systems and work with multiple stakeholders.

The research carried out for this report suggests that the new care model sites did not rush to create new organisational forms and contractual arrangements. Instead, often building on years of work before the programme, they used informal partnerships to develop collaborative relationships and redesign care. This was supported by programme governance structures that brought together senior leaders from the respective organisations.

These approaches involved testing many new and different cross-organisational care pathways and teams simultaneously. Sites did this by creating new teams and roles, new ways of sharing information and new locations for providing treatment. Activities were coordinated through local overarching programmes. By bringing together the different strands of work in this way, teams aimed to avoid the pitfalls that can occur when interventions are designed in isolation. Studies show these common pitfalls can lead to duplications, inefficiency and confusion for patients.

‘There’s so much duplication and so much complexity that the right hand sometimes doesn’t know what the left hand is doing… [What is needed is] stepping back a bit and saying, “what do we mean by new care models?” These are the component parts, let’s put these component parts together and stop treating them as separate entities.’

Clinical lead, EHCH

Formal changes to governance and organisational arrangements were considered by the sites later in the development of the new care model. These were based on what they had learned during the process of care redesign about what was needed to remove barriers to further change and align organisational incentives.

‘The tenth [and final] strand of work was commission and contract but it’s interesting that it’s the tenth… you don’t do that until you’ve planned, you’ve designed, you’ve developed, you’ve mobilised, because it should be the tying of the ribbon.’

Deputy chief officer, CCG

This section distils these insights from the sites into 10 lessons that may be helpful for those involved in developing and implementing new care models (Figure 2). These lessons have been drawn from common themes identified during interviews, and reviews of academic literature on cross-organisational change and the literature produced by new care models sites.

The 10 lessons are categorised into three stages:

- initiating change

- developing plans

- implementing new models.

These stages and their lessons are interconnected and should not be understood as strictly linear. The complexity of local health and care systems means there will be inherent messiness and unpredictability. As changes are made they will impact upon the local context and, as with a plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle, time should be taken to understand this.

Figure 2: 10 lessons to support new care models locally

Initiating change

1. Start by focusing on a specific population

The published national frameworks suggest new care models segment their populations based on level of need and then deliver appropriate care across the whole population in the geographic area they are responsible for.,, When beginning to develop new care models, however, the vanguard sites in this research focused first on smaller populations or cohorts of patients with similar needs. This enabled the sites to gain experience of working together on new approaches to understanding the needs of, and engaging with, these populations.

Populations can be segmented in different ways, including by geography, age and conditions. MCPs and PACSs covering GP registered populations larger than 100,000 commonly used localities of 30,000–50,000 as an organising principle for service delivery.* Within these localities they further segmented populations based on need – such as focusing on groups of patients with a defined chronic condition.

‘Your local stamp is you know where best to focus your attention and you know the populations to start thinking about.’

GP lead, MCP

Sites said data was essential for understanding the needs of these population groups. This meant they had to spend time developing the infrastructure for data collection and exploring options for analysing the data, such as risk stratification tools. This process helped sites learn about the challenges of such analysis and adapt their approach when focusing on other groups. NHS England has set up the population health analytics network to collate the learning from this, bring together guidance and offer peer support.

As well as using data to identify need, sites discussed the value of involving patients and their families at the beginning of care redesign – the benefits of this have been described extensively in the literature on large-scale change.

The sites acknowledged that at times they found involving people locally difficult due to time pressures, but focusing first on a smaller segment of the population helped them develop and test ways of doing this successfully. One such method was asking patients and families to say what was important to them, which focused care development on the creation of the right outcomes. For example, an EHCH used ‘I’ statements† to co-design desired outcomes for care home residents – building on previous work by National Voices.

2. Involve primary care from the start

The vanguard sites spoken to for this research emphasised the importance of involving local GPs and primary care providers throughout the process of developing a new care model, irrespective of the model type. Primary care plays an essential role in delivering coordinated care for patients, families and communities and is an essential foundation for building new care models. GPs offer significant insight into the needs of populations and where services can be developed to improve care across organisations.

‘The care model is absolutely embedded within general practice and wider primary care.’

GP lead, EHCH

Given the current pressures within primary care and the range of models of primary care across the country,, sites described the importance of working closely with local GPs to determine the pace of change and how much they were involved in the new care model.

‘It’s been quite a big process of not feeling like we’ve forced primary care into anything… “By this point in time you have to have done this” or “You have to have done the other” or “You have to be this kind of organisation”. So, that’s enabled them to have a bit of thinking time. Equally, they also recognise that… they can’t do it on their own anymore.’

Programme lead, PACS

There is a risk that in larger STP or ACS geographies – where individual practices and general practice organisations have smaller catchment areas than acute trusts – meaningful engagement with primary care could be neglected when developing new care models.

This could lead to general practice disengaging – some examples of this have been seen among negative responses to new care models in the general practice trade press. GPs have also appeared dissatisfied with plans for new care models in some areas where they were not initially involved. Local leaders working in these footprints must consider how they will address this when developing new care models.

The varying ways the vanguards engaged with primary care offer some insight into possible approaches. In some sites there were established GP organisations that could act as the lead provider for the new care model. In others, vanguard leaders supported the growth of new GP alliances or organisations, which included providing administrative personnel and funding, or offered leadership roles within the vanguards to individual GPs.

3. Go where the energy is

Sites described taking a pragmatic approach to deciding which areas to focus on when developing new care models. This involved identifying clinical individuals and teams that already had ideas for and commitment to change. This helped sites gain momentum by engaging with those willing to lead change locally. It also helped to mitigate against potential staff fatigue induced by top-down ideas.

‘Sometimes we used to bang our heads against a wall, but now, I think you have to go with the willing, and the hearts and the minds.’

Project manager, MCP

Vanguard leaders highlighted the importance of a thorough review of their sites to look for engaged individuals across all levels of organisations, but particularly clinicians who had previously been involved in implementing plans locally.,

‘It’s absolutely crucial that you map out what care redesign is going on in and around your area and look at the commonalities and the differences. Look at the key people who are leading some of that change. Then also, similarly, map out some of the conversations that are happening.’

GP lead, EHCH

Sites used different strategies for mapping exercises. Many undertook the time-intensive work of getting out to as many providers as possible to speak to staff. Sites used various techniques to find out where work was happening that they were not aware of – particularly in the community. For example, a large MCP attracted clinicians to multiple well-publicised meetings to make decisions about how to use vanguard funding. In another MCP, the creation of new lead clinician roles created interest among relevant individuals.

Making early progress helped to build momentum for further change, creating belief among sceptics and reinforcing the backing of others. The example in Box 1, from an EHCH site, describes how the site used the learning from first working with a small number of care homes to then help develop the strategy for care for older people on a larger scale across the STP geography.

Box 1: Care home vanguard – developing a strategy to improve care

‘We decided we’d try and think about how we can work with our care home sector to support them to deliver care in the sector. We started a pilot programme – myself and a nurse and manager from community services – to look at how we’d start improving care within care homes. That programme itself basically then just evolved over the last 6 to 7 years…

‘It’s definitely grown, it’s found its natural links with other elements of care beyond care homes, moving particularly into the intermediate care section and that interface with secondary care particularly. So, I do think that there is lots of learning and a tremendous amount that we can take forward [in the STP].’

GP lead, EHCH

4. Work through shared understanding of challenges

Part of the hard work of making changes across boundaries is moving from the initial enthusiasm to creating clear objectives across organisations. Many sites began with an initial vision created by a small group of often senior leaders. They then brought together staff and patients to discuss and agree clear objectives. This began with working through a shared understanding of the problems to be solved – a crucial factor in cross-team improvement work.

Bringing together teams from across organisations in this way was a time-intensive process. Finding dedicated time for stakeholders to develop new relationships and nurture established ones was essential – the process sought to bring the tensions and preconceptions of individuals, many of whom had a history of working alongside each other, to the surface.

‘Those professional relationships are very enduring and are embedded in other social relationships. Doctors tend to work together and play together. So, there’s other social structures and mechanisms going on outside of all of that. So, the engagement pieces, they are really massive.’

Medical consultant, MCP

Some sites initially used external facilitation, and some continued to use it throughout the programme.

‘What has been different is actually bringing everybody together and starting the relationship… Part of the MCP process has been a programme where business psychologists brought everybody together in a room. It was a monthly meeting for half a day, six sessions, bringing together patients, voluntary sector, all different sorts of people, as well as community providers, primary care.’

GP lead, MCP

Some vanguards found such an approach more difficult due to geography and lack of available staff to cover for clinicians. In these cases, programme leads spent more time going out to different parts of the system to understand stakeholders’ views. It may take longer to build trust this way compared to bringing people together in person, but could be a pragmatic approach for sites given the pressures on the workforce.

Developing plans

5. Work through and challenge assumptions around how activities will achieve results

There is an inevitable risk with all change work in health care that local areas may rush to implementation without being clear on the ‘specifics of desired behaviours, the social and technical processes they seek to alter... [how] proposed interventions might achieve their hoped-for effects in practice, and the methods by which their impact will be assessed’.

In the case of the new care models programme, the national team sought to mitigate this risk by requiring vanguard sites to use programme theory – specifically logic models. A logic model is a diagram or visual map of the relationship between a programme’s resources, activities and intended results – it also identifies the theory or assumptions underpinning the design of a programme’

This visual representation is designed to fit on one side of a page. But given the complexity of the interventions, sites often used multiple interrelated logic models for different areas of the programme to capture the varying levels of detail.‡

Sites used facilitated workshops to design these models. They generally felt that coming together in workshops and creating the logic models was positive for the design of their interventions locally. It supported them to think through and discuss links between planned activities and outputs, and draw out risks and enabling factors. In some cases, it altered the course of action.

‘People are often really good at standing up and describing all the great impacts we’re going to have, and then describing a set of interventions, without necessarily thinking through the logic of why is it that these actions and interventions will deliver those impacts, and, for us, going through that process was really helpful.’

Programme lead, PACS

Another benefit was that, in some cases, these workshops operated as an ‘equalising tool’ for power dynamics within local systems, building on earlier work to develop local relationships. The workshops created an environment that actively encouraged ‘silly questions’ and challenged assumptions. Some areas described how this approach provided a platform to start encouraging these questions as part of everyday work.

‘Managers of teams or front-line staff… are [now] always asking questions like “What’s the problem here?”, “What are we going to do about it?”, “Why are we going to do it in that way?”, “What assumptions are we holding in doing that?”’

Lead evaluator, MCP

Some sites expressed frustration with the compressed timetable set by the national programme for creating logic models. They felt it limited their ability to effectively bring partners together. Those seeking to use logic models should, therefore, carefully consider the time and people required to do this in a meaningful way at the outset, to avoid the process becoming a box-ticking exercise.

Several sites also reflected that it had been useful to revisit the logic model to work through the potential impact of changes of course and new activities. This suggests that it is more effective to use the logic model as a live product rather than a one-off document that is then filed away in a drawer.§

6. Find ways to learn from others and assess suitability of interventions

Many clinicians and managers working in the vanguard sites used formal and informal networks within and across specialties. These enabled sharing of learning and ideas. The central programme initiated some of these networks, such as facilitated programmes for the different new care model types, while others were pre-existing. The central team also created an online FutureNHS collaboration platform to share learning.

Through these networks, those involved in the sites learned about approaches and interventions others were using, not only in the UK but also internationally. This was made possible by giving people time to attend events, both virtually and in person, and sharing what they had learned upon their return.

‘Vanguards are... a rapidly evolving blend of ideas and initiatives: new and old, home-grown and imported, large and small.’

Those interviewed for this report said it was important to spend time thinking through how or if new or imported interventions might work in their local contexts. This involved regularly bringing stakeholders together and seeking out further data that would aid decision making. This process also helped to encourage staff to own the changes. The example in Box 2 describes how an MCP adapted an intervention in this way.

Box 2: Multispecialty community provider – developing a local intervention

‘We wanted to set up a breathlessness clinic because we had seen it implemented in another vanguard.

‘[Working with the respiratory consultants in the local hospital] we wanted to look at the demand first. So, we did an audit in a local hospital around demands for breathlessness referrals, and what we found was [in the geography] there were not high referrals for breathlessness, but there was an absolute high demand in secondary care for referrals of coughs.

‘We then facilitated a GP-targeted event around how they manage coughs, and every single GP sat in the room managed coughs differently. Between the consultants in the hospital, and our GP lead for respiratory, we developed a new cough care pathway [modelled on the breathlessness clinic, but not identical].’

General manager, MCP

Implementing new models

7. Set up an ‘engine room’ for change

While implementing new care models, organisations within the vanguards worked in informal partnerships. Staff were needed for coordination across several areas, including administrative and project management, engagement activities and effective programme governance.

All the vanguard sites featured in this report had a dedicated central project team that brought staff and activities together, described in the MCP framework as an ‘engine room to drive and manage the local transformation programme, with adequate dedicated resources and capabilities’. In the literature on implementation, these central teams are a key factor in achieving change when embarking on unfamiliar activities.,

It was important that these teams included staff who had already worked in the local health and care system, to create confidence among stakeholders and increase how quickly teams could start, thanks to their existing knowledge of the areas. The size of teams in the vanguard sites varied, but skills within them included project management, quality improvement, data analysis, communication and administrative expertise. In some of the larger vanguards, team members were placed directly in the localities and other clinical redesign groups.

Many sites used the additional funding from the national programme to backfill staff vacancies or create new roles where needed. Some sites were uncertain how they would continue after the national programme, and its additional funds, ended – not least because in some cases this related to future job security. However, some sites did have plans to continue their teams, and site leaders had spent time building the case for their continued existence, particularly as part of STP activities. There was a strategic move by sites to explicitly align themselves to local STP agendas.

‘The shift has been for us about moving our programme away from it being a shiny new project over there, and moving it towards being a system-wide transformation programme.’

Programme director, PACS

There was also one example of a team created at the beginning of the programme without using the additional national transformation funds. In this case the site pooled roles and clinical time from across organisations, including the CCG, into one team focused on the new care models work. In some areas, therefore, there may be means of creating such a resource without significant investment – although there would need to be consideration of how this would affect other activities.

8. Distribute decision-making roles

The complexity of the changes in vanguard sites meant that responsibility for making change happen could not be held centrally. Senior leaders within vanguards took steps to distribute decision-making roles throughout the organisations and professional groups within the vanguard, and across various levels of leadership.

Forums for centralised senior decision making within the sites were needed where decisions affected multiple groups – decisions about distribution of transformation funding, for example – and to oversee governance of the sites. These forums brought together senior leaders and representatives from local groups within the vanguards. They were often hosted by the organisation that had led the bid (including CCGs) and were coordinated by the central project teams.

The composition of these forums determined their effectiveness. A review of centralisation of stroke services found that credible representation from different clinical groups in such forums was important for leveraging respect from clinicians across the system. The vanguard sites also considered this to be necessary.

In one PACS, a senior clinical leader felt their vanguard had not got the composition right at first – this had led to stakeholders feeling that the senior leadership team were pushing for change for the benefit of one organisation at the expense of others. In this case, the team picked up on this early through regular feedback-gathering events and evened out representation across clinical groups in their central decision-making forum. There had been concerns that, had the initial composition remained, whole organisations and professional groups would have felt increasingly disenfranchised.

Importantly, the vanguard sites also created forums for stakeholders to come together in smaller groups, for example by heading up a locality or leading specific areas of clinical redesign work. These groups provided spaces for open discussion – a key element that helped to strengthen relationships.

‘We need[ed] to develop a safe environment for clinicians to get together, where they improve the communications, develop better relationships, real relationships. Then, do stuff together, basically.’

GP lead, PACS

The sites experimented with different ways of bringing together leaders and members of the smaller groups to share updates, learn and connect to the wider vision of the new care models programme. Finding the right format required learning and adaptation, and trying to get it right could be frustrating at times. Sites found they had to be flexible – approaches included the use of morning telephone conferences, large in-person events and evening meetings.

9. Invest in workforce development at all levels

With the creation of new services across organisations, vanguard sites said investing in the development of staff with the right skills for these changes was crucial. This was necessary at all levels of the local systems and focused on aligning the efforts of staff with the aims of the vanguards.

Approaches to leadership development varied – some sites used external courses while others created in-house, cohort-based leadership programmes. Sites considered this essential to the success of the new care models.

‘[This gave] everyone a shared sense of what our aims and objectives are, and autonomy and licence to achieve that. Within some limits, but [with] a huge amount of autonomy... I’m absolutely convinced it’s down to the leadership development and the cascading of that across the entire team.’

Medical consultant, MCP

New multidisciplinary teams were brought together in facilitated sessions to agree on their values, ways of working and to discuss what would help them operate more effectively as a team. Co-location of office space for multidisciplinary teams was a common request.

‘Having a little bit of power for themselves to change some things internally and think through how they were working maybe gave people a bit of confidence to think that they could work slightly differently.’

Medical lead, PACS

Many local leaders found creating clinical roles to enable new ways of working and new career opportunities was difficult to tackle at their level in the system, despite describing it as a key part of their work streams.

‘Workforce was a real tough area. I felt like I was wading through treacle… who holds the key to it all?’

Programme lead, EHCH

Yet some sites reported success in developing and recruiting new roles, such as musculoskeletal practitioners to work alongside GPs. There were also examples of sites developing cross-professional competency and skill frameworks. One new care model site worked with a local university to develop a competency framework for all clinical staff working with their older population. Others worked more directly with certain groups of clinical staff to support them to take on new skills and roles – such as nurse-led referrals and increased roles for community pharmacy. By demonstrating the benefits of such approaches through these pilots, sites built confidence among the wider workforce.

10. Test, evaluate and adapt for continuous improvement

Multiple changes were taking place within the vanguard sites, with many of these changes starting from different stages of development, at different points in time. Some sites focused on running services in parallel while others introduced outright changes to existing services. This was often dependent on the level of confidence in the model and engagement of the clinical teams and patient groups, especially where the work had been done in other areas locally prior to the programme.

Due to the complexity of the new care models, there was a strong focus on understanding what was happening, evaluating and measuring impact, and building on the initial work as part of the logic model process. Sites described the importance of using this information to help shape their plans as they progressed.

‘The process of just taking stock and reflecting things back to [sites] did, I think, help to form some consensus and help to sharpen focus on some particular areas.’

Lead evaluator, MCP

Ascertaining clear cause and effect in these complex systems was not a simple task.

‘Of course, the rest of the world doesn’t stand still, so as much as you might have a project doing one thing in a particular area then there are a number of people operationally in their day-to-day work tinkering away and making changes that actually you’ve got no real control over. It’s not a nice sterile environment that says that A equalled B, produced C. So, it’s a real challenge.’

Programme lead, PACS

This does not undermine the role of evaluation, but rather emphasises the need for teams to continually challenge themselves and to look for new forms of information to understand what is happening. Lessons from research into safety suggest that this should also involve seeking uncomfortable and challenging information to alert teams to blind spots.

Sites used different partners for evaluation, including academic health science networks, universities, commissioning support units and consultancies. In one STP, three vanguards pooled resources to do this more effectively. All the sites in this report worked closely with data analysts locally – they provided them with additional support and co-located them with the central change teams and clinical leaders.

‘We have those frequent conversations, you know your watercooler conversations, or we’ll just pop down and have a chat about something because the data looks a bit funny and we want to understand it. I don’t think you can overestimate how important that is.’

Lead data analyst, PACS site

The vanguards benefitted from funding for these evaluations, but new local areas seeking to develop and implement new care models may not be in such a fortunate position, and may face limited availability of data analysts locally. There is, therefore, a need for local systems seeking to develop new care models to think strategically about how they can develop their evaluation capability over time, perhaps by using participation in national programmes or other initiatives as a building block. This might also require a shift in thinking that enables an intuitive questioning approach to develop.

‘We’re starting to think about ways in which you could set up systems to be self-improving and learning, and one of the ways in which I think you can do that is to give people a set of ways of thinking and ways of approaching problems that are those that you would use in an evaluation.’

Lead evaluator, MCP

Even with access to this evaluation support, it could be challenging for sites when feedback showed an intervention had not worked. Sites then had to deal with the impact of perceived failure on individuals, particularly those who had taken on a leadership role. To do this, they focused on the time that had been spent on leadership and team development, to encourage those involved to focus on next steps as opposed to becoming disengaged. In the example in Box 3, a GP lead describes implementing change within an A&E, how different forms of feedback demonstrated that change was not working, and how it created a radical shift in the PACS’s approach to change.

Box 3: Primary and acute care system – learning from failure

‘We thought, “What a great idea. Let’s get GPs in A&E,” but there was not any historical context for this. We found strong cultures – different cultures – did not allow that to happen and it failed completely after multiple attempts.

‘How did this affect me as a person? I needed to reflect. I felt a bit demotivated. I thought, “This isn’t going to work. I’ve got better things to do.” It’s almost like you need to mitigate this in starting off things like this because failures are often a catalyst of complete failures if we’re not careful.

‘I re-engaged again because of another conversation with the chief of service for the Emergency Department (and other colleagues)… Learning from that failure, he came up with a triage system in A&E… so, we’re supporting that. So, out of that failure came this new thing.’

GP lead, PACS

Where measurement and evaluation activities are used for performance management there may be less scope to learn from failure. Giving teams time to learn through testing was therefore important. The new care models sites said this flexibility decreased over the course of the programme as the focus on return on investment became tighter.

* It is also the size used by the National Association of Primary Care’s primary care home models. See: http://napc.co.uk/primary-care-home

† ‘I’ statements focus on the feelings or beliefs of the speaker, rather than the thoughts and characteristics that the speaker attributes to the listener.

‡ Not all logic models have been published. For an example of a vanguard’s logic model, see: www.slideshare.net/WessexAHSN/north-east-hampshire-and-farnham-vanguard-for-innovation-forum-jan-16

§ The Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit has created further guidance on logic modelling: https://midlandsandlancashirecsu.nhs.uk/images/Logic_Model_Guide_AGA_2262_ARTWORK_FINAL_07.09.16_1.pdf

Implications for the future

The desire to change the delivery of care to better meet the needs of those who require support across health and care services is not new. A 1972 NHS white paper acknowledged that ‘a single family, or an individual, may... need many types of health and social care and those needs should be met in a coordinated manner’. The fact there have been so many policies to deliver change reflects the difficulty in making that change happen in complex local health and care systems.

The research for this report identified 10 key lessons to support providers and commissioners seeking an approach to change that emphasises local co-creation and testing of care models. It also highlighted implications for leaders of these sites, as well as for national policymakers and regulators who are actively seeking to encourage the proliferation of new care models.

For local health and social care leaders

New care models are built on old foundations

Context, both historical and current, must be assessed and understood before embarking on change. This includes consideration of previous change initiatives and whether they can be built upon, as well as taking time to understand pre-existing organisations and relationships. Sites may find it better to start with a smaller geography and specific population. This will also help with the daunting exercise of collecting and making sense of this information.

Focus on care redesign and delivery first – new governance and organisational form arrangements should not be rushed

In the absence of a new organisational structure, practical support must be put in place to enable the different organisations to better work together. The creation of a dedicated project team that includes administrative, improvement and communication skills to oversee and support this is important – as is a clear structure for decision making that goes beyond senior leadership.

Reserve more time than you might think to bring people together to support co-design

This model of collaborative working must begin at the planning stage for new care models and continue throughout implementation. For it to be effective, time should be protected for staff to work in this way, and is likely to require multiple methods of communication. Those skilled in change management and organisational development can help facilitate this collaboration at key points – such as in the initial phases of bringing people together and when developing logic models.

Evaluation should be considered a core component

Change that involves numerous organisations with many moving parts is gradual and involves testing multiple new ideas simultaneously. Evaluating to understand what works is a core component of this and local systems must think strategically about how they can develop their evaluation capability over time.

This requires local areas to invest in evaluation infrastructure – that is, the technology and staff to support the collection and analysis of data – as well as expose teams to evaluation to improve understanding of cause and effect and create a climate that is open to constructive feedback.

For national policymakers and regulators

Support new and existing systems

The new care models programme developed an innovative approach that set out to create a relationship between national and local areas, and support sites by giving them the time and headspace to do the essential work of care redesign. The vanguards felt the programme team had been mostly successful in doing this, although they noticed a shift from proactive support to a greater focus on demonstrating tangible results as the programme progressed.

The question now facing national policymakers is what do the national performance, governance and regulatory frameworks need to look like to support the local development of new models of care across the country? The answer to this is being tested through the creation of new ACSs – an opportunity that offers parts of the STP geographies that have shown the greatest progress in developing new care models greater autonomy by ‘tear[ing] down administrative, financial, philosophical and practical barriers’.

Yet for those areas that are in a more formative stage of making these changes, while dealing with significant performance priorities and financial pressures, it seems there may need to be a different answer to this question. There must be recognition that there are unlikely to be shortcuts for new areas to achieve these changes and that change may require additional investment. Time should also be spent understanding how the short-term actions of the national bodies and their regional outposts inhibit these longer-term changes.

Send the right message

Sites did not describe changes to organisational and governance structures as initial catalysts for wider change. NHS England’s contracting support documents also state a new care model ‘cannot simply be willed into being through a transactional contracting process’ – this has been reiterated by a recent report on emerging forms of innovation and governance in the new care models. Yet this message does at times appear to get lost within the current environment.

A desire among national policymakers to make complicated systems appear neat by focusing on restructuring organisations and tendering new contracts from the outset is understandable given the current pressures to deliver improvement at pace. Yet this research suggests this approach may neglect the groundwork required to make meaningful changes to the way care is delivered. The core aims could become distorted – from ‘how can we improve the care for patients in this area?’ to ‘how can this area become a PACS, MCP or ACS quickly?’

There is also a risk that a focus on restructuring providers may disrupt some of the productive relationships that already exist within local health and care systems. CCGs, for example, were valued stakeholders in the development of many of the new care models. They operated as a support function to bring organisations together and nurtured the development of cross-organisational relationships. This is a positive role that CCGs may be able to play in some local health economies.

Continue to build evaluation capabilities and capacity

There is broad consensus that focusing on joined up care and avoiding siloed work is the right thing to do for patients. But it is essential for policymakers and regulators to invest in local and national evaluation capabilities and capacity, to understand if these changes are improving care.

At local level, evaluation not only enables system leaders to understand whether changes have improved services, but can also lead to better understanding of how interventions work and can be implemented. Participation in national initiatives may be a key building block in improving this capacity locally. And health data analysts must not be a forgotten part of the government’s upcoming national workforce strategy.

The proliferation of similar interventions among the vanguard sites further emphasises the need for continual and robust local evaluation to be both synthesised and replicated at a national level. There is a risk that what works and why will not be properly understood and shared if there is a rush to roll out new care models.

Where to next?

The new care models programme was an attempt to do something genuinely different to make change happen, by providing support for local leaders to enable them to collaborate to improve care for their local populations. In exploring what these local leaders did and understood to be important to make changes, this report found a predominant focus on actions that fostered collaboration and built development and evaluation capacity.

Although the new care models programme is drawing to a close in 2018, wider application of the programme’s approach to supporting local change could have a substantial impact on the health and care of the population, particularly those who currently fall through the gaps of service fragmentation.

Appendix: Selected national change initiatives, 2008–17

|

Year |

Initiative |

Stated purpose |

|

2008 |

Next stage review: Our vision for primary and community care |

Commitment to improve access to primary care through extended opening hours and GP-led health centres. Introduced the concept of ‘integrated care organisations’ in which provider or commissioner organisations could merge or operate under single budgets to deliver integrated care. |

|

Care closer to home project |

Project set up to demonstrate how care can be delivered closer to home in defined service areas. |

|

|

Transforming community services |

To improve the quality of community services through structural changes. |

|

|

Whole system demonstrator programme |

The whole system demonstrator programme was set up by the Department of Health to show what telehealth and telecare is capable of; provide a clear evidence base to support important investment decisions; and show how the technology supports people to live independently, take control and be responsible for their own health and care. |

|

|

2009 |

Integrated care pilots |

Local health and social care organisations supported by the Department of Health to explore ways to integrate care. |

|

2010 |

Quality, innovation, productivity and prevention programme |

Large-scale national programme to improve the quality and efficiency of health care, with a focus on reducing hospital utilisation. |

|

2012 |

NHS funding transfer to local authorities |

This announced the transfer of annual funding from the NHS Commissioning Board to local authorities to improve integrated working (announced via the care and support white paper and ultimately replaced by the Better Care Fund). |

|

Shared commitment to integrated care |

A framework that outlines ways to improve health and social care integration (in the wake of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act). |

|

|

2013 |

Integrated care programme pioneers |

Developing and testing new and different ways of joining up health and social care services across England. |

|

Better Care Fund |

A single, pooled local budget to incentivise the NHS and local government to work more closely together to make wellbeing the focus of health and care services (announced in 2013, began 2015/16). |

|

|

Prime Minster’s challenge fund |

Funding for sites to help improve general practice and produce innovative models of primary care. |

|

|

2014 |

Transforming primary care |

Set out plans for more proactive, personalised and joined up care, including the proactive care programme, for those with complex health and care needs. |

|

2015 |

Sustainability and transformation plans/partnerships |

Every health and care system will be required to work together to produce a sustainability and transformation plan (now known as partnerships), covering the period from October 2016 to March 2021. |

|

Primary care homes |

Developed by the National Association of Primary Care (NAPC), this is testing a model that brings together a range of health and social care professionals to work together to provide enhanced personalised and preventative care for their local community. |

|

|

New care models programme |

Supporting local areas to develop and test new models of joining up health and social care services across England. |

|

|

Integrated personal commissioning |

A programme that is supporting health care empowerment and the better integration of services across England. |

|

|

Success regimes |

A regime to address longstanding issues, and create the conditions for success in the most challenged health and care economies. |

|

|

Devolution deals and the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act |

This has signalled the readiness of the government to have conversations with any area about the powers that area wishes to be devolved to it, and about their proposals for the governance to support these powers if devolved. |

|

|

Quality in a place programme |

A programme to understand the extend to which the Care Quality Commission can provide evidence to support whether reporting on the quality of care in a place can be a lever for improvement. |

|

|

2016 |

New health and social care dashboard |

Assessing the flow of patients across the boundary between the NHS and social care. |

|

2017 |

Accountable care systems |

Health and care systems that have demonstrated progress in integrating care will be given more control and freedom over the total operations of the health system in their area. |

Source: Stated purposes taken from various documents: 2008,,,, 2009, 2010, 2012,, 2013,,, 2014, 2015,,,,,,, 2016, 2017.

References

- NHS England. Five year forward view. 2014. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

- Calkin S. ‘New care models’ to cover half of England. Health Service Journal. 23 October 2014. Available from: www.hsj.co.uk/new-care-models-to-cover-half-of-england/5075999.article

- NHS England. Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. 2017. Available from www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf

- Department of Health. The Government’s mandate to NHS England for 2017-18. 2017. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-mandate-2017-to-2018

- Fielding, NG. Challenging others’ challenges: Critical qualitative inquiry and the production of knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry. 2016;23(1):17–26. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1077800416657104

- NHS England. The multispecialty community provider (MCP) emerging care model and contract framework. 2016. Available from www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mcp-care-model-frmwrk.pdf

- NHS England. Integrated primary and acute care systems (PACS) – Describing the care model and the business model. 2016. Available from www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/pacs-framework.pdf

- NHS England. The framework for enhanced health in care homes. 2016. Available from www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/ehch-framework-v2.pdf

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW and Whittington J. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27(3):759–769. Available from: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/27/3/759.abstract

- NHS England, the Care Quality Commission, Health Education England, Public Health England, Monitor and the NHS Trust Development Authority. The forward view into action: Registering interest to join the new models of care programme. 2015. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/moc-care-eoi-guid.pdf

- David Williams. Where the £200m national transformation fund was spent. Health Service Journal. 14 April 2016. Available from www.hsj.co.uk/sectors/commissioning/revealed-where-the-200m-national-transformation-fund-was-spent/7004007.article

- NHS England. Approved New Care Models Programme vanguard funding allocation. 2016. Available from www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/apprvd-vanguard-fund.pdf

- Allcock C, Dormon F, Taunt R, Dixon D. Constructive comfort: accelerating change in the NHS. Health Foundation; 2015. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/constructive-comfort-accelerating-change-nhs

- NHS England, the Care Quality Commission, Health Education England, Public Health England, Monitor and the NHS Trust Development Authority. The forward view into action. New care models: support for the vanguards. December 2015. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/acc-uec-support-package.pdf

- NHS England. Evaluation strategy for new care model vanguards. 2016. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ncm-evaluation-strategy-may-2016.pdf

- Tallack C. Evidence emerging from evaluation of the new care models. Available from: www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/charles-tallack-evaluation-new-care-models

- The Health Foundation. Improvement Analytics Unit. Available from: www.health.org.uk/programmes/projects/improvement-analytics-unit

- NHS England, the Care Quality Commission, Health Education England, Public Health England, Monitor and the NHS Trust Development Authority. The forward view into action: Planning for 2015/16. 2014. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/forward-view-plning.pdf

- Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Øvretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context: A selection of essays considering the role of context in successful quality improvement. Health Foundation; 2014. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/perspectives-context

- Bate P. Perspectives on context: Context is everything. Health Foundation; 2014. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PerspectivesOnContextBateContextIsEverything.pdf

- Salisbury C, Thomas C, O’Cathain A et al. Telehealth in chronic disease: Mixed-methods study to develop the TECH conceptual model for intervention design and evaluation. BMJ Open, 2015;5:e006448. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/2/e006448

- Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity Science: The Challenge of Complexity in Health Care. BMJ. 2001;323(7):625–8. Available from www.bmj.com/content/323/7313/625

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Plan-do-study-act (PDSA) worksheet. Available from: www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx

- Lewis G. Why population health analytics will be vital for the vanguards. NHS England; 2016. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/blog/geraint-lewis-2

- Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, Saul JE, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Quarterly. 2012;90(3):421–56. Available from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3479379

- National Voices. A narrative for person-centred coordinated care. 2013. Available from www.nationalvoices.org.uk/publications/our-publications/narrative-person-centred-coordinated-care

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83:457–502. Available from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16202000

- Davies E, Martin S and Gershlick B. Under pressure: What the Commonwealth Fund’s 2015 international survey of general practitioners means for the UK. Health Foundation; 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/under-pressure

- Smith J, Holder H, Edwards N, et al. Securing the future of general practice: New models of primary care. The King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust; 2013. Available from: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/securing-the-future-general-practice-summary-web-final.pdf

- Lind S, Price C. GPs to do weekly care home rounds under new NHS England plan. Pulse. 30 September 2016. Available from: www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/more-clinical-areas/elderly-care/gps-to-do-weekly-care-home-rounds-under-new-nhs-england-plan/20032921.article

- Senge P, Smith B, Kruschwitz N, Laur J, Schley S. The necessary revolution: How individuals are working together to create a sustainable world. Nicholas Brealey Publishing; 2010.

- Bohmer R. Presentation to the Nuffield Trust Summit: Opening plenary. 4 March 2016. Available from:www.summit.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/agenda-2016/2016/3/4/session-6-opening-keynote-on-the-role-of-middle-management

- Vize R. The revolution will be improvised: Stories and insights about transforming systems. Systems Leadership Steering Group; 2014. Available from: http://leadershipforchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Revolution-will-be-improvised-publication-v31.pdf

- Sutton E, Dixon-Woods M, Tarrant C. Ethnographic process evaluation of a quality improvement project to improve transitions of care for older people. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010988. Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010988

- Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B, Seccombe I. Rising pressure: the NHS workforce challenge. Health Foundation; 2017. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/rising-pressure-nhs-workforce-challenge

- Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety. Published online first: 23 January 2015. Available from: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/early/2015/01/23/bmjqs-2014-003627#article-bottom

- Kaplan SA, Garrett KE. The Use of Logic Models by Community-Based Initiatives. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2005;28:167–72 Available from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.467.1199&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- NHS England. Operational Research and Evaluation Unit Learning Paper: Learning from the new care models programme vanguards’ logic models [unpublished].

- Health Foundation. Effective networks for improvement: Developing and managing effective networks to support quality improvement in healthcare. 2014. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/EffectiveNetworksForImprovement.pdf

- NHS. FutureNHS collaboration platform. Available from: https://future.nhs.uk/connect.ti

- Batye F. Dudley’s local evaluation: headlines from year 1. NHS Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit. Available from: https://midlandsandlancashirecsu.nhs.uk/about-us/publications/new-care-models/217-yr1summaryslides/file

- Pannick S, Sevdalis N, Athanasiou T. Beyond clinical engagement: a pragmatic model for quality improvement interventions, aligning clinical and managerial priorities. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2016;25:716–25 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004453

- OPM. Evaluation of the NHS breathlessness pilots: Report of the evaluation findings. 2016. Available from: www.opm.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Breathlessness-Report-6April.pdf

- Hickson DJ, Miller SJ, Wilson DC. Planned or prioritised? Two options in the implementation of strategic decisions. Journal of Management Studies. 40(7):1803–36. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00401

- Pronovost PJ, Mathews SC, Chute CG, Rosen A. Creating a purpose-driven learning and improving health system: The Johns Hopkins Medicine quality and safety experience. Learning Health Systems. 2017;1:e10018. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/lrh2.10018/full

- Turner S, Ramsay A, Perry C, et al. Lessons for major system change: centralization of stroke services in two metropolitan areas of England. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2016;21(3):156–65. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4904350/#bibr14-1355819615626189

- Dixon-Woods M, et al. Culture and behaviour in the English NHS: Overview of lessons from a large multi-method study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2014;23:106–15. Available from: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/23/2/106

- Deeny S, Steventon A. Making sense of the shadows: priorities for creating a learning healthcare system based on routinely collected data. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2015;24:505–15. Available from: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/24/8/505

- Bardsley M. Understanding analytical capability in health care: Do we have more data than insight? Health Foundation; 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/understanding-analytical-capability-health-care

- Wistow G. Still a fine mess? Local government and the NHS 1962 to 2012. London School of Economics and Political Science; 2012. Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/43322/1/__Libfile_repository_Content_Wistow,%20G_Wistow_Still_fine_mess_Wistow_Still%20_Fine_%20Mess.pdf

- Health Foundation. Evaluation: what to consider – Commonly asked questions about how to approach evaluation of quality improvement in health care. 2015. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/EvaluationWhatToConsider.pdf

- NHS England. NHS moves to end ‘fractured’ care system. 15 June 2017. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/2017/06/nhs-moves-to-end-fractured-care-system/

- NHS England. New care models: Procurement and assurance approach. 2017. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/1693_DraftMCP-4_A.pdf

- Collins B. New care models: Emerging innovations in governance and organisational form. The King’s Fund; 2016. Available from: www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/New_care_models_Kings_Fund_Oct_2016.pdf

- Lintern S. Government to announce single NHS workforce strategy. Health Safety Journal. 7 November 2017. Available from: www.hsj.co.uk/workforce/exclusive-government-to-announce-single-nhs-workforce-strategy/7020982.article

- Department of Health. Whole system demonstrator programme: Headline findings – December 2011. 2011. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215264/dh_131689.pdf

- Department of Health. Transforming Community Services. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/TCS/index.htm

- Department of Health. Care closer to home project. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Ourhealthourcareoursay/DH_4139717

- Department of Health. NHS next stage review: Our vision for primary and community care. 2008. Available from: www.nhshistory.net/dhvisionphc.pdf

- Department of Health. National evaluation of DH integrated care pilots. 2012. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-evaluation-of-department-of-healths-integrated-care-pilots

- The Lancet. QIPP Programme (Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention). 2012. Available from: http://ukpolicymatters.thelancet.com/qipp-programme-quality-innovation-productivity-and-prevention

- Department of Health. Integrated care: our shared commitment. 2013. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/integrated-care

- Gallagher S. Funding transfer from the NHS to social care in 2013/14 – what to expect. 19 December 2012. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-funding-transfer-to-local-authorities

- SQW, Mott McDonald. Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund: Improving access to general practice – first evaluation report. 2015. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/pmcf-wv-one-eval-report.pdf

- NHS England. Better Care Fund. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/part-rel/transformation-fund/bcf-plan

- NHS England. Integrated Care Pioneers. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/integrated-care-pioneers

- Department of Health. Transforming primary care: safe, proactive, personalised care for those who need it most. 2014. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/304139/Transforming_primary_care.pdf

- Care Quality Commission. Pilot project to build picture of the quality of care in local areas. 2015. Available from: www.cqc.org.uk/news/stories/pilot-project-build-picture-quality-care-local-areas

- The House of Commons. Cities and Local Government Devolution Bill: explanatory notes. 2015. Available from: www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/2015-2016/0064/en/16064en.pdf

- NHS. Five year forward view – The success regime: a whole systems intervention. 2015. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/432130/5YFV_Success_Regime_A_whole_systems_intervention_PDF.pdf

- NHS England. What is integrated personal commissioning (IPC)? Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/ipc/what-is-integrated-personal-commissioning-ipc

- NHS England. New care models: vanguards – developing a blueprint for the future of NHS and care services. 2016. Available from: Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/new_care_models.pdf

- NHS England. Primary care home model. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/new-care-models/pchamm

- NHS England. NHS leaders set out new long-term approach to sustainability and transformation. 2015. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/2015/12/long-term-approach

- Department of Health. Local area performance metrics. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-area-performance-metrics-and-ambitions

- NHS England. Integrating care locally. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/five-year-forward-view/next-steps-on-the-nhs-five-year-forward-view/integrating-care-locally