Introduction

This section will help you plan your communications activity and focus your communications on where they can make the most impact.

By working through this section you will be able to:

- understand the basic principles of good research communications

- identify the resources required for your communications

- hear what funders are looking for in dissemination or communications plans

- identify the audiences that you will need to engage with as a priority

- see the range of communications channels available and decide the right ones for you

- set out your approach in a simple communications strategy.

There are three parts to this section:

- Using strategic communications planning to increase impact.

- Identifying and prioritising audiences.

- Choosing the right communications channels.

Read some funders’ perspectives on the growing importance of good research communications, as well as some tips for laying out your communications plans at the funding application stage.

Read about funders’ views on research communications.

Using strategic communications planning to increase impact

Good communications need to be planned, resourced and delivered. The most systematic way of doing this is to create a simple communications strategy.

It is important to set aside time to create a well-planned strategy. Increasingly, funders are looking for evidence on how you will meaningfully engage policy, practice and public audiences with your research findings. A clear, innovative communications strategy could increase the appeal of your research to funders and, ultimately, its impact.

Use a template to set your communications objectives.

Read about how to identify and secure communications support and resource.

Develop your communications strategy with a template.

Identifying and prioritising audiences

If you understand who your most important audiences are, you can tailor your communications to their specific interests, needs and motivations.

The better you know your audiences, and the more you tailor your communications to them, the more effective your communications will be. This may seem obvious but is often overlooked, even by seasoned communicators.

Find out how to identify and prioritise your audiences.

Read about engaging public and patient organisations with your findings.

Choosing the right communications channels

You can use many different channels to transmit information or messages to specific audiences, and the number is constantly growing. Examples include conferences, journals, blogs, websites, email and social media, such as Twitter and Facebook.

Being able to identify the channels that are right for your audiences, your research and the resources you have available is important.

The decisions you make here will dictate how you allocate your time and budget, and will also give a strong indication of the skills you will need as your project progresses.

Read a guide to communications channels.

The funders’ view

Why do funders want to see findings communicated beyond the research community?

'We hope to bring about change and to do that we need to put good evidence into the right hands. It’s all about impact.'

Darshan Patel, Senior Research Manager, the Health Foundation

The driver for communicating findings beyond the academic and research community is impact. Researchers and funders both want to drive positive change. Research can bring greater evidence or insight to policy, practitioner and public audiences; funders want researchers to demonstrate that they can target and engage those audiences in their findings.

As a secondary factor, the Research Excellence Framework requires academic institutions to demonstrate how their research activities achieve wider impact – that is, an effect on, change to, or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment, or quality of life, beyond academia.

'We know that the most beautifully conducted research does not automatically lead to changes in practice or policy. Funders feel a strong obligation to get the best value from the awards they make and that means having robust plans for how you will communicate those findings to the audiences that matter most.'

Dr Natalie Armstrong, Professor of Healthcare Improvement Research (with several years’ service on funding panels assessing health-related research applications)

What are funders looking for in research communications?

Funders have identified the following as communications approaches that they would like to see reflected more in funding applications and research communications.

- A proactive approach to communications and as great a commitment to appropriate dissemination as to research quality.

- Analysis and identification of the potential audiences for research findings at the outset of a study. Find out how to identify and prioritise audiences.

- A strategic communications approach: a demonstration of strategic analysis and efficient, targeted use of communications resources. Develop your communications strategy with a template.

- An accurate indication of the time and resource required to communicate findings to priority audiences.

- Making more of the opportunities to engage with key audiences during the course of a study, not just when findings are available. Read case study 1 in Influencing a policy audience.

- Employing communications channels that are focused on target audiences’ needs – rather than falling back on those that are familiar and/or already used by the research team. Read a guide to communications channels.

- Thoughtful adaptation of the format, language, content and messaging around findings for key audiences. Find out how to create messages for different audiences.

'We do not expect researchers to be able to communicate with everyone, all the time. However, knowing who your audiences are will help when planning a communications strategy. It will also make implementation of your dissemination strategy quicker and more impactful.'

Neha Issar-Brown, Programme Manager (Population and Systems Medicine Board), Medical Research Council

Download this chapter as a PDF

Setting communications objectives: a template

Identifying and securing communications support and resource

Why do you need communications support?

Achieving impact through your research requires wide communications and engagement. It is important to factor this activity into your planning at an early stage.

Ideally you should include the time and costs involved in communications activity in your funding application. This is particularly important where communications are likely to be integral to the success of the research. This means identifying the additional skills you may need and the people who will be able to help you. It also means providing a broad estimate of any associated costs.

Typical research communications tasks include the following.

- Creating and managing a communications strategy or plan, managing interest in your research and keeping stakeholders up to date in the research process – for example, through updates on social media.

- Running engagement events that bring stakeholders together in the early stages of the work or which help to publicise the findings more widely later on.

- Writing accessible copy tailored to the needs of different audiences that communicates the aims of your research, its findings and implications – for example, policy briefings, press releases or online articles.

- Designing, producing and commissioning creative ways of communicating your findings – for example, through the use of infographics or film.

It can be difficult to plan your communications before you know your findings. However, it is all too easy for researchers to underestimate the potential for and value of wider communication, as well as the time and skills required to do this effectively.

There are many free tools and training courses on offer to help those communicating their research, but tapping into these can be prohibitively time-consuming. It may be better to find additional support.

Where can you find communications support?

Depending on the type of research you are involved in and where you work, some of the following support options may be open to you.

UK universities

Have central marketing and communications teams and/or staff based within individual faculties or schools. Most institutions will have a central media office that can support researchers in working with journalists, normally where their research is newsworthy or high profile. Many also have central creative services teams who can produce films or design imagery for faculty staff where a budget is available. A few of the most research-intensive universities employ research communications staff who will be on the lookout for engaging or high-impact research stories to communicate more widely.

NHS communications staff

Tend to be largely focused on communications around service delivery and patient care. Trusts that are members of the Shelford Group are more likely to have communications staff with some capacity to support researchers in communicating their work, particularly where the research is seen to be of particular relevance to the trust’s stakeholders, and/or where it might help to enhance the trust’s reputation.

Research funders

Will sometimes support the communication of research that is particularly high profile or which links into their wider communications objectives. This may include issuing joint press releases or involving researchers in stakeholder events. For example, the Health Foundation has involved some of its funded researchers in webinars on patient safety, the role of context in improvement work and achieving value in health services.

Research partners (eg health charities, groups representing patients and/or the public)

May help to communicate the research where it helps them achieve their wider goals.

Many experienced freelancers (and some communications agencies)

Specialise in science or research communications and can be contracted directly to support your research. Do check first whether your employer imposes any restrictions on the use of external providers.

Grants

Are also available for researchers who plan to engage public audiences in their work.

You may need to keep research sponsors or funders, your employer or host organisation and research partners informed about your communications plans. If you are using external support, make sure the supplier is aware of this requirement.

Finding freelance or agency support

Where in-house communications staff do not have the capacity to help individual research teams, it is common for researchers to involve experienced communications freelancers or agencies. Many of these will charge by the hour or day for their services.

If you think this is likely to be the case for your research, you should include an estimate of the costs and the predicted benefits in your application for funding.

To find the most appropriate support, you’ll need to be clear about the communications work involved so that you can identify people with the right skillset. The following networks might help you find people with experience in research communications.

- Communications, marketing or public engagement staff in your organisation: ask if they know of reliable freelancers or agencies with relevant skills. University communications staff may also be a member of STEMPRA, a network of more than 250 science public relations (PR), communications and media professionals. Many members use this network to seek recommendations about freelancers or agencies.

- The National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement: runs a Public Engagement Network for people with an interest in engaging public audiences in research. It is open to anyone with an interest in the subject. Members interact through a JISCMail list.

More general online networks are also available, such as People Per Hour and Upwork, which link up freelancers with prospective clients.

If you are employing a freelancer or agency relatively unknown to you, it is a good idea to first take up references from former clients. Many will also provide a brief proposal with an estimate of costs and a summary of their experience and skills.

If you decide to engage their services, you can then ask for a signed letter of agreement or short contract outlining what they will deliver and the costs that will be incurred (fees, expenses, VAT etc). This should detail any additional commitments you require from them – for example, the key deadlines you need them to meet and/or a clause on the appropriate use of confidential information or data.

Download this chapter as a PDF

Download the guide to identifying and securing communications support and resource.

Developing a communications strategy: a template

Identifying and prioritising your audiences

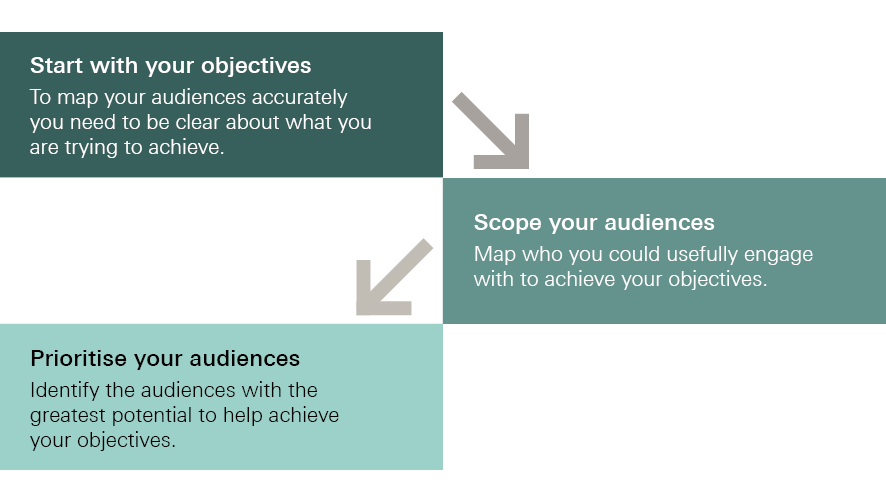

The three steps to identifying and prioritising your audiences

Knowing which audiences to focus on as a priority will make your communications approach more efficient and effective. Developing a clear view of who you are trying to communicate with and why, and tailoring your approach to their particular needs, interests and challenges, is a process. Investing time at the outset of your study to work through this process and reviewing those choices at key points during the study is central to a strategic communications approach.

Researchers can scope and prioritise audiences using a three-step tool. The process helps you identify the most relevant groups and individuals for your research communications: those that have both potentially high levels of interest in your research findings and the ability to use them in a way that informs debate, policy or practice.

The three steps to scope and prioritise your audience

1. Start with your objectives

Identifying your priority audience(s) starts with your communications objectives. However, these objectives may change throughout the course of a research study.

For example, at the beginning of your study you may wish to engage with audiences that can help shape your research and approach. Midway, there may be insights emerging that will impact on practice or policy audiences and you may wish to engage with them around the implications of those insights before your study has concluded. Once research is complete and findings are available, your audience focus may expand to include policymakers, practitioners or members of the public.

The task in this first step is to clarify the communications objectives against which you will scope and prioritise your audiences.

2. Map your audiences

The focused question for this part of the process is: who could we engage with to achieve our communications objective(s) and why?

The task is to set out all the groups that could potentially help to achieve your objectives (or act as a barrier to you achieving them). If possible, this brainstorming is best done as a group so that you are able to bring different ideas and perspectives to it.

A mapping tool

The following lists have been split into types of audiences and populated with some generic examples. It may be helpful to use this type of format to prompt lateral thinking and to record results. Please see the tips for use before starting the exercise.

Delivery

Who must you engage with in order to ensure the communication of your research?

- Patient groups.

- Clinical leads in X.

- Nursing staff in Y.

- Research partners.

- Funders.

- University public affairs offices.

Peers and partners

Who may wish to partner or help?

- Charities.

- Think tanks.

- Research departments in other institutions.

- Funders.

- Royal colleges/professional associations.

Beneficiaries

Who will benefit from your study?

- Patient groups.

- Staff groups.

- Clinical staff.

- Executive boards.

- Policymakers (local, regional, national).

- Groups of the general public.

Detractors

Who could act as a barrier to the successful communication of your study or be a significant detractor?

- Competitors for resource.

- Patient groups.

- Pressure groups

- Charities.

- Media – traditional and social.

Influencers

Who influences the agenda and thinking around this issue? Who do your other audiences respect and trust as a source of information?

- NHS England/Wales/Scotland/Northern Ireland.

- Royal colleges or similar.

- Care Quality Commission/NHS Improvement.

- Media, blogs (strictly ‘channels’ but can be important in own right).

- Think tanks.

- MPs/parliamentarians.

- Well-known individuals.

- Medical/patient charities.

- Funders.

Power brokers

Who has the decision-making power associated with your study’s findings? Who can make the final decision around policy and practice changes?

- NHS England/Wales/Scotland/Northern Ireland.

- MPs.

- Government departments.

- Parliamentary groups (select committees, all-party parliamentary groups).

- Do not attempt to judge or prioritise any audiences. Simply record all ideas.

- Lateral thinking is good at this stage. The task is to record as many potentially relevant audiences as possible.

- Only use the category prompts in the tables if they feel helpful. You can adapt the categories if others feel more relevant to your study, or not segment them at all. Do whatever feels most helpful to you and your team when gathering ideas.

- It does not matter if the same audience appears in more than one category. In fact, this could be an early indication of their importance to your communications.

- Where possible, be specific (ie try not to record ‘the Department of Health’, but the specific departments, regions, posts or even individuals that you could connect with). Never record categories like ‘the public’, ‘patients’, ‘health care staff’ or other large generic groups – this does not help to focus your communications. However, in the first instance, you may need to record broad audience categories that feel important and undertake further research to refine and focus them.

Output

At the end of this mapping process you will have a list of potential types of audiences you could engage with to achieve your communications objectives.

Next steps

- A useful exercise in early prioritisation is to look at your long list and ask the questions: Why do we want to engage with this audience? How will they help us achieve our objective(s)?

- If necessary, do more research to refine the audiences you have identified. If there are individuals you feel are absolutely key to engage with in order to effectively communicate your findings, then list them as an audience. The tighter the focus, the more efficient your communications can be.

3. Prioritise your audiences

After you have identified all of the audiences you could engage with, the next task is to prioritise the most vital ones. The fewer target audiences you have, the more focused your communications can be. The aim is to identify at least four, but no more than six, priority audiences.

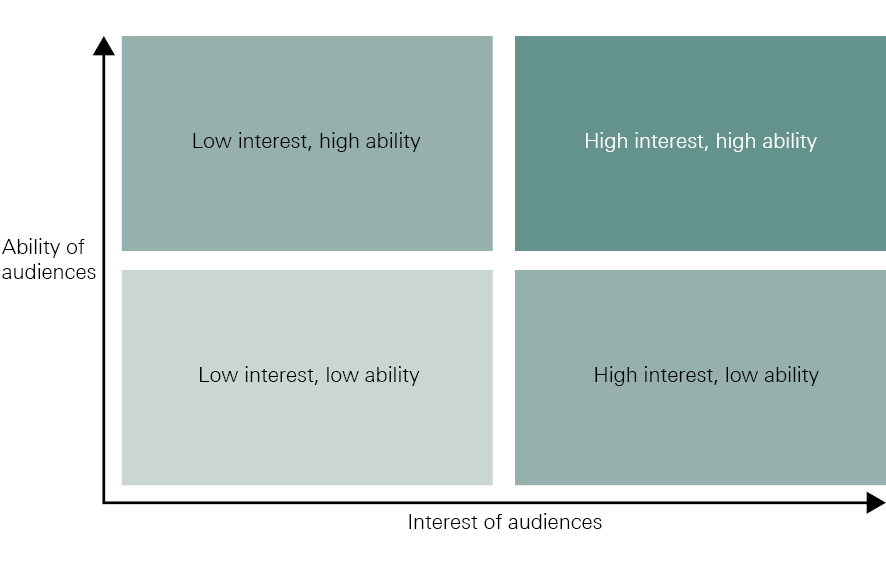

A prioritisation tool

The interest–ability matrix in this section can help you prioritise your mapped audiences.

You may wish to do an initial instinctive trawl of the audiences identified in the mapping exercise. Lateral thinking is good but do you have any that you know, even at this stage, will not be a key audience for your research communications? If so, weed them out now.

Write the remaining potential audiences on sticky notes, one per note. Taking one at a time, place the audience on the matrix below in response to the following questions:

- What level of interest does this audience have, or potentially have, in the research that we are undertaking/our knowledge/our research insights?

- What level of ability does this audience have in helping us achieve our communications objectives?

The interest–ability matrix: interpreting the results

- All audiences that sit in the top right quadrant have high levels of interest in your research and they are in a good position to help you achieve your objectives (they make or influence the directly relevant policy, practice or behaviours). Strategically, these are going to be the most relevant audiences to target your communications at.

- All audiences that sit in the bottom right quadrant have a shared interest in your area of research but have little direct influence on, or ability to achieve, your objectives. In communications terms it might be appropriate to keep these audiences aware or broadly informed about your work (eg updates via Twitter or e-newsletters) but not concentrate resources on them.

- All audiences that sit in the top left quadrant have low levels of interest in what you are trying to achieve but potentially high influence on, or ability to achieve, your objectives. Key influential detractors could sit here too – they are not interested in seeing you achieve your objectives but may have a high ability to disrupt/prevent you from achieving them. Bear in mind that audiences in this quadrant may be important but will be harder to reach and require more communications resources to engage than those in the top right quadrant.

- All audiences that sit in the bottom left quadrant have low levels of interest in your objectives and low levels of ability to achieve or influence your objectives. In most instances, you can take these out of your communications plans.

Identifying your priorities

- The most easily engaged audiences will be those in the top right quadrant.

- In some circumstances, you may wish to target those in the top left (low (current) interest/high ability). But, be aware that it is likely to require more time and resources to engage these audiences.

- It is rare to prioritise any audiences in the bottom two quadrants, although you may decide to keep those in the bottom right-hand quadrant (high interest/low ability) informed of your study.

- Helpful questions to ask when doing this final prioritisation may include:

- Who holds the key decision-making power around these findings?

- Who will champion these findings above all others?

- Who stands to benefit most from these insights?

Output

At the end of this prioritisation process you will have a list of four to six priority audiences for your study’s communications.

Next steps

Record those audiences in the communications strategy template and use this focus to guide decisions on channels, messages, etc.

Download this chapter as a PDF

Download the guide to identifying and prioritising your audiences.

Engaging public and patient organisations with your findings

Why involve public and patient organisations?

Involving public and patient organisations can help you do the following.

- Shape your communications approach: they may bring important insights into how patients experience their care, or they may know about policy debates that are relevant to your area of study. This will help you ensure that your research communications are as relevant as possible, and could help you avoid some potential blind alleys.

- Plan how you will engage patients, and identify relevant individuals or groups: researchers that collaborate with patients aim to tap into their expertise and experiences to solve problems together. Some charities have extensive expertise in involving patients or carers in their work, and may be able to provide advice on the skills, techniques and resources required to identify and involve people with a range of physical and mental health needs.

- Engage a wider audience with your findings: if your research has the potential to throw up important questions or insights that are relevant to patients, you may need to plan how you will share your findings with public audiences. Public and patient organisations can help you understand patients’ perspectives on the issue you are studying, and advise on how to go about communicating your findings to them. They may help you to anticipate their concerns or information needs.

If you have established a good relationship and demonstrated how your research can help public and patient organisations with their goals, they will be more likely to help you disseminate your findings through their established networks and channels. They may also be willing to actively champion your research if the findings have the potential to enhance care and knowledge for the people they represent.

Who to involve?

The organisations you might involve are entirely dependent on the nature and scope of your research, whether you are involving patients in the research process, and the extent to which your findings are likely to have broader relevance to patients. These organisations might include:

- the Health Research Authority and local research ethics committees (RECs), for research involving patients in the NHS. They should be able to provide advice on good practice for involving patients in research and help you determine when ethics approval will be necessary

- patient involvement or public engagement staff working in the NHS, universities and research institutes

- national charities that support people with specific health conditions, such as Macmillan Cancer Support, or which champion the needs of certain groups (eg Age UK or Mencap). In addition to providing services directly to patients, larger charities typically have well-established policy and communications functions. See the Association of Medical Research Charities for a list

- small- to medium-sized patient groups or charities working locally or regionally. Many are independent bodies, while others operate as part of a larger umbrella national charity or network. See Patient UK’s online tool for identifying relevant support groups for patients

- networks that bring people together with a specific interest in how patients or the public are engaged and involved – for example, the Patient Experience Network, the Coalition for Collaborative Care, Involve or the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE).

How to engage public and patient organisations

For some researchers, the first step is to invite representatives of public and patient organisations to engagement events involving a range of other stakeholders. Where a research project has a more formalised partnership in place with a public or patient organisation, there may be a requirement to involve them through a steering or advisory group.

As health problems may prohibit individual patients from taking on extended commitments, representatives of patient organisations and charities are often asked to champion their needs and experiences through roles on committees or advisory groups.

For such a group, operating effectively depends on:

- clearly defined roles, with a shared understanding of what is expected of external representatives

- clarity about which aspects of the work they can influence

- the skills and knowledge of the individuals involved and their ability to influence the communication of research findings appropriately.

Involving patients directly

If you are directly involving patients, carers and communities in helping to communicate your work, it will be important to assess whether you have the skills, resources and capacity within your team to listen to and build good two-way relationships. This might include providing training and support, and will almost certainly involve some financial resource – for example, expenses for travel and refreshments.

Charities like Macmillan Cancer Support often use trained patient advocates to work alongside patients and help them express their stories, priorities and needs.

'When involving patients, it’s the detail that counts. If you’re asking patients to speak up in meetings, you will need to provide them with appropriate training and support. If you’re asking them to travel to events, you will need to pay expenses up front.'

Professor Jane Maher, Chief Medical Officer, Macmillan Cancer Support

Patients are often highly invested in the subject matter of their condition, treatment or care. The NCCPE has produced an introductory guide on anticipating the ethical and social issues that might be involved.

Communicating your findings with patients

'The patient perspective is key. Their voice is a very effective communications tool.'

Michael Nation, Development Director, Kidney Research UK

If you have involved patient and public-facing organisations from the outset of your research, listened to them and kept in touch with them, you may find you have established a pool of potential advocates that you can call upon to reach others. Patient advocates and stories can be a powerful means of bringing research insights to life for clinicians, commissioners and policymakers.

Resources

- How to involve people in your research: a guide by Involve.

- Researchers’ experiences of patient and public involvement: a compilation via Healthtalk.

- Research Councils UK case study: Professor Irene Hardill’s account of her work with voluntary sector organisations.

- Planning your public engagement: a guide by the Wellcome Trust.

- Planning your public engagement: a resource from the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement.

Download this chapter as a PDF

Download the guide to engaging public and patient organisations with your findings.

Communications channels

What to consider when choosing communications channels

When deciding which communications channels to invest in, the starting point should be your audiences. Which channels are most likely to reach and engage your audiences? Which do they already use and trust?

The second consideration is how much detail they’ll require from you in order to engage with your study and findings. If your audience comprises policymakers actively developing policy in your area of research, their appetite for detail will be high, and the communications channels you choose will need to accommodate that. If your findings relate to informing new approaches among time-pressed practitioners, you may need to summarise or break down your insights and communicate with them little and often.

By starting from your audiences’ perspectives it is possible to resist the impulse to revert automatically to channels that you have used previously or that you are already familiar with. The following table gives a brief rundown of some of the main communications channels for researchers, their key benefits and some considerations for use.

Journals

Good for:

- peer review

- communicating findings to other researchers/experts in your field

- advancing knowledge

- building awareness of research

- building credibility of your research

- career advancement.

Consider

- Is the journal’s coverage a good match with your study?

- Publishing is evolving – explore electronic-only journals and open access publications if they feel right for your work.

- Check restrictions (such as word count, open access fees, their position on communicating before journal publication) to avoid problems or disappointment down the line.

- Impact factor is important for academic purposes but high impact factor may not mean a wide readership.

Conferences, group meetings, workshops

Good for:

- listening

- brainstorming

- relationship building

- building and sharing purpose

- exchange of complex

- learning and information

- building trust and loyalty

- engaging early adopters.

Consider

- Time and cost resource: do participants have sufficient time and/or motivation to attend?

- Timing and location: make it easy and/or appealing to attend, or piggyback onto existing meetings.

- Format: ensure everyone has time to participate and contribute.

1:1 meetings

Good for:

- engaging influencers or stakeholders

- building knowledge and trust

- building or maintaining key relationships.

Consider

- The messages you want to communicate in the meeting and how to follow up to ensure the relationship is maintained.

Social media (eg Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn)

Good for:

- finding or creating networks with niche specialisation or interests

- building a profile

- directing to other communications

- brief, real-time updates

- maintaining relationships

- exchange of information/learning

- place for like-minded to interact

- reaching early adopters.

Consider

- Content: who will post and regularly update/respond? Need to allow time to react/respond to others’ posts to build relationships.

- How you can use this to cross-promote other communications (such as an online blog or journal article).

Media coverage (professional and consumer media)

Good for:

- credibility (a third-party endorsement) and reputation

- internal morale

- improving awareness among public/lay audiences

- influencing debates and agendas.

Consider

- Time and skills required: need to be able to respond to any interest in very short timeframes; less ability to ‘control’ the message.

- Plan any media activity with the knowledge of your institute’s media office and consider which kind of media (professional/consumer) is right for your audience and message.

Websites (and/or intranet sites)

Good for:

- credibility

- demonstrating full range of work

- attracting new audiences

- information exchange

- accessibility.

Consider

- Time and cost resource for initial and ongoing development: ability to keep up to date; analytics for evaluating use/impact.

- Creating a web page hosted on the website of the sponsor organisation/partners.

Blogs

Good for:

- demonstrating expertise, learning and knowledge transfer

- content for social media

- can boost traffic to website

- place for like-minded to interact.

Consider

- Content: a catchy title; a subject your audience cares about; a central point, argument or call to action.

- Promoting the blog through social media channels.

Good for:

- low-cost, regular updates

- driving traffic to website or blog.

Consider

- Writing style and visuals: emails are easy to delete.

- Ensure that content and look is audience-focused and stands out from the crowd.

Online networks

Good for:

- facilitating information exchange

- building a community.

Consider

- Cloud-based and ListServ technology make this possible and affordable.

- Easy to set up groups through social media (eg LinkedIn), but they need to be actively maintained.

Launch events

Good for:

- internal morale

- stakeholder awareness

- can provide a hook for media coverage.

Consider

- Time and cost resource: do target audiences have sufficient time and/or motivation to attend?

- Timing and location: make it easy and/or appealing to attend.

- Media coverage: do you have something genuinely newsworthy?

Webinars

Good for:

- exchange of complex information or learning

- maintaining relationships

- project management among dispersed teams.

Consider

- Scheduling: think of a time likely to be convenient to most participants.

- Promoting: make sure people know about it and remind them.

- Organising: give it some leadership and structure; ensure the content is engaging.

Film and animations

Good for:

- creating an emotional connection with a cause

- telling stories that can illustrate complex issues

- engaging people who don’t tend to read anything

- longevity – post online on YouTube or Vimeo (can be used in different settings – eg insert in presentations, play on screen in waiting areas).

Consider

- Resource and budgets: how will you promote, distribute or make it available to ensure return on investment?

- Length: online films should be as short as possible (1–3 minutes as a general rule).

Here are some digital and online multimedia tools and channels to consider using in your communications.

Videos

Use, benefits and considerations

- Good for showing at meetings and events, and provides a legacy for the study.

- Brings life to ideas and concepts and, if done well, is an engaging way of telling a story and sharing the perspective of staff or patients.

- Increasingly produced by amateurs. If involving a film production company allow at least £1,500 per ‘talking head’, and at least £4,000 if filming on location (eg in a hospital).

- People are increasingly used to watching video online, especially with the rise of mobile and tablet use. Upload films to YouTube, which increases visibility of content in Google searches.

Audio slideshows

Use, benefits and considerations

- Quick-win content, especially if a presentation has already been prepared for offline use (at a conference).

- Cheap to produce (around £300) and fairly quick to turn around.

- Can help to explain and illustrate ideas at the same time (through voice and visuals).

- Slideshows can also be uploaded to Slideshare (open source software), which increases visibility of content.

Audio clips

Use, benefits and considerations

- Cheap to produce (around £300) and quick to turnaround.

- Shouldn’t be too long (maximum 5 minutes) unless it’s very engaging.

- You can create free audio clips using the Audioboom app.

Animations

Use, benefits and considerations

- Can be creative with visuals to convey complex ideas, especially when you’re referring to and interpreting lots of figures.

- Expensive and resource-intensive to produce. Expect to pay £7,000 and upwards.

Infographics

Use, benefits and considerations

- Visual way of communicating data rather than using a simple chart or written copy – great for illustrating what data means, quickly.

- Can be flat infographics that are available as sets to download and use, or interactive.

- Good for sharing on social media, especially Facebook where image-led updates get the highest levels of engagement.

- Costs would be around £300 for non-interactive, but increase significantly for interactive versions.

Prezi

Use, benefits and considerations

- Low-cost tool for creating interactive presentations.

- Good for presenting content that is detailed and joins up in various ways – plays in a linear way but you can explore slides however you like.

- Can simply be a more engaging tool with which to present compared to PowerPoint.

- Can embed videos, links, etc, which you can’t do in an audio slideshow.

Download this chapter as a PDF

Social media in research

The benefits of social media

Social media (Twitter, blogging, LinkedIn, etc) gives researchers the means to find and connect with new audiences and communicate directly with those that have an interest in their research.

Building a following and achieving impact through any social media channel requires commitment, but with the right input it can be a remarkably effective and cost-efficient channel for research communication.

Potential benefits include:

- identifying and reaching new audiences – including those beyond academia

- access to senior decision makers and influencers

- increasing awareness for, and support of, your work

- building networks and forming a community that can amplify your insights and findings

- keeping up to date with developments and news in your field

- building your own profile

- the ability to participate remotely in debates around conferences, events, or news happenings

- contributing to impact (eg boosting Altmetric scores).

The pace of change and development in social media channels and tools is constant and it can be difficult to keep up. A range of the most relevant and frequently employed tools in a research context can be found in the communications channels guide. Further resources are listed at the end of this document.

The NHS Confederation identifies Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook and YouTube as the social media channels most actively used by health care audiences in the UK. Scoping research for this toolkit indicates that blogging can also be particularly effective in leading to new connections and influence.

A free micro-blogging service that enables users to post short messages (up to 140 characters) and include URL links and images. It is widely used by academics, practitioners, policymakers and influencers.

Getting started

Sign up at www.twitter.com. Choose a name that strikes the balance between being easy to remember, and personal yet professional (as you will be using this in a work capacity). Twitter has excellent resources to guide beginners. Start modestly, perhaps following a small number of colleagues and people you already know well. This gives you the opportunity to understand the practicalities of messaging, hashtags, retweets, etc before growing your follower base.

There is no pressure to post original content from day one. Identifying the right people to follow, reading what they are tweeting, familiarising yourself with styles and topics, then responding to or retweeting some of their messages (after which they may follow you back) is a constructive beginning.

Use it for:

- promoting any aspect of your research study or other communications – new blogs, presentations, website updates, publications, etc. (If links are to content that sits behind a paywall, make this clear – for example write ‘£paywall’ – or provide an open web full version or summary)

- joining the conversation around subjects related to your research area

- understanding how opinion and debates are shifting in real time

- becoming a ‘go to’ resource in your research area – tweeting/retweeting about relevant new journal articles, government policy, conference presentations, etc.

Make full use of Twitter by:

- using it to identify influencers and create a community of interest. Twitter allows you to identify potential influencers by looking at their number of followers and observing whose tweets are regularly retweeted. Hashtags and keywords allow you to quickly find those with an interest in your research subject(s). Directory tools like Followerwonk can be trialled for free and enable searches of Twitter bios for specific terms.

- measuring impact – beyond number of followers you are able to monitor how many people are clicking on links you share through free-to-use tools like bit.ly. For a small fee, tools like

- Twittercounter enables you to see how many mentions your organisation or research subject is getting over a period of time.

Blogging

Writing based on your own knowledge, observations or opinion that is published online, either via your own online blogging platform or on one that gathers blogs from many contributors. Widely used in academia, blogs tend to be short (400–800 words) and employ a more informal writing style.

Getting started

Some funding awards require the creation of a website, which can then be used as a blogging platform. Established blogging platforms like WordPress.org and Blogger offer start-up blogging sites for little or no outlay and have easy-to-use interfaces. Most websites vary in terms of cost, additional functionality and security features. As with Twitter, the name you choose for your blogging site is important. Select something authentic to you and your work, that will be relevant and memorable for your audiences.

In addition to your own site there are established online publishing sites for researchers. These include, but are not limited to: The Conversation; Academia.edu; LSE British Politics and Policy blog; The Thesis Whisperer; and Manchester Policy Blogs. All place an emphasis on accessibility in presenting findings and most have large Twitter followings to cross-promote blogging entries – so they can have a large audience reach. Likewise, most universities and some health care institutions publish blogs on their websites.

A blog provides an opportunity to communicate about your research in a more informal or conversational way. By finding and using your authentic voice and personal experience, it can make your research more accessible and bring it to life for a wide range of audiences. Remember, however, that a blog post is still a publication. And be mindful of how much research detail you want to make public before your findings are peer-reviewed.

Funders like the Health Foundation host blogs on their websites and may be worth approaching with ideas related to their organisational interests, particularly if you are in receipt of one of their grants.

Use it for:

- translating more technical research findings into an engaging and accessible format for a wider range of audiences

- establishing knowledge in a specialist area before research findings are available

- promoting your research during the course of a study, rather than focusing all communications resources towards the end

- providing more depth to your online profile and providing content that you can use to promote via Twitter, e-news, etc.

Make full use of blogging by:

- setting up an RSS feed for your blog. This enables visitors to your site with ‘feed readers’ to indicate an ongoing interest in it. The RSS feed will alert them when you’ve published a new post

- tagging your posts so that they are categorised. This will improve the chances of your posts being found by search engines

- using images that bring life and interest to your posts. There are various websites that provide royalty-free images for use and some, like Free Images, have dedicated health and medical sections.

LinkedIn is a professional networking site. It enables users to establish and grow an online professional network that starts with existing connections and can be built up to include connections’ connections. You can post short updates or messages to the site, and even publish blogs, which everyone in your network will be notified about.

Getting started

You can create a profile as an individual researcher or as a research team or department. LinkedIn will ask you to provide previous career/research experience and enables you to nominate specialist areas of interest or expertise that make you ‘searchable’ by other contacts.

Once you have established your own profile you can start linking to existing contacts – either manually or using LinkedIn’s syncing software. Ensure that you review your public profile settings (in Privacy & Settings > Edit your public profile) so that people can see your profile and find/connect with you if you wish them to.

Use it for:

- building your professional profile and connections

- keeping up to date with new posts/positions within your network

- identifying or establishing a community of common interest.

Make full use of LinkedIn by:

- joining in relevant debates or discussions on topics relevant to your research

- re-publishing any blogs or short, accessible pieces of writing.

Promoting your social media updates

Research insight and well-crafted copy alone will not drive visitors to your social media channels. You will need to promote them at every suitable opportunity.

Think of your channels as equal in importance to your email address in terms of contact details – include them in business cards, email signatures, conference presentations, etc.

Managing risk

All communications involve an element of reputational risk. That risk is not necessarily greater with social media, but issues can spread quickly. However, it is possible to manage the risks with some practise and sensible tools.

- Make a conscious decision about how much of your study you wish to communicate about on the internet. Issues to consider include plagiarism, self-plagiarism, publishing before peer-review and some journals’ sensitivities around exclusive publishing. In most cases there will be much that you can say about your study with no risk at all, but be mindful about putting findings and conclusions out there before peer-reviewed publication.

- Consider copyrighting your work via a free-to-use service such as Creative Commons. This should afford any written work, such as blogs, some degree of protection.

- Monitor your channels regularly and use the free monitoring tools that come with many channels and platforms to keep up to date with new comments, follows, mentions, etc. If an issue arises, act quickly. Don’t be afraid to block any abuse or inappropriate contribution, but respond with sensitivity if it concerns issues such as patient groups or individual patient cases.

Integrating social media with your other communications

Social media profiles and high numbers of followers are not the end goals. In the context of communicating your findings and knowledge, it is simply another channel. You will maximise your communication reach if you work across a range of channels. So, if you have a journal article you can point to it with Twitter, and write a corresponding blog that contains some audio, which can then be brought to the attention of journalists. Content needs to be crafted for each channel to achieve effective communication. By putting out consistent, appropriately tailored messages across various channels, you will provide more chances of reaching all your target audiences.

- A comprehensive list of social media resources and tools is available from the Research Information Network

- The Economic and Social Research Council’s guide to social media for researchers includes a good level of detail on how to use Twitter from scratch

- A survey by Cogitamus for the NHS Confederation in 2012 focuses on current use, future trends and opportunities in public sector social media.

- The Guardian Higher Education Network Blog provides 10 top tips for academic blogging.

- NHS IQ’s The Edge is a hub for change activists in health to exchange information and ideas.

Download this chapter as a PDF

Planning engagement events

Practical tips on the best ways to share research findings through events

An engagement event is an event that directly engages research users, participants, interested parties and/or beneficiaries. Events such as workshops, roundtable discussions and seminars can enable researchers to actively involve people in their findings.

Why hold engagement events?

Once researchers have subjected their findings to peer review or another form of critical appraisal, they may wish to engage wider audiences in their findings.

The benefits of hosting a discussion event about interim or full findings can include the following.

- sense-checking the findings: whether you involve policymakers, health providers, other researchers, practitioners and/or patient representatives, they will all have a different perspective to bring on the relevance and significance of your findings

- gaining buy-in and generating interest: taking the time to meet face-to-face with people who your research findings might affect can make a huge difference to how they feel about your research. They may also be able to advise you on, and support you with, your approach to dissemination. Policy audiences also often appreciate a heads-up on what the research is showing.

Factors to think about when planning your event

Planning an event is highly time- and resource-intensive. It may also not be the most cost-effective way of engaging people in your research findings, particularly if you can piggyback onto existing meetings and events that your target audiences already attend.

If you have the requirement and resource to run your own events, you will need to allow enough time for planning. Large events involving 200 or more people often take a year to plan, and even smaller events for around 20 people are typically planned over a matter of months rather than weeks. You will need to book the venue and the speakers well ahead of time, and to assess their availability before you finalise the date.

Your event should be designed around the needs and interests of your audience, as well as your own objectives. Consider their motivations for attending, and ensure that these will be addressed by the speakers, content and format of the event.

For example, policymakers may value smaller events that allow for much more in-depth exchanges among a group of people with particular expertise to share. Small and highly targeted events can also be much more productive for the researchers hosting them, particularly where the subject matter is complex and/or they are seeking specialist input.

Bear in mind any constraints faced by those you want to involve, particularly around the timing and venue. For example, consider that:

- clinicians often need a minimum of six weeks’ notice to take time out of a clinic

- policymakers may expect you to travel to them, and their diaries may already be booked up months in advance

- stakeholders, especially patients, may have requirements that will need to be accommodated, such as disabled access and hearing impairment aids.

Agree an agenda or terms of reference that can be circulated in advance so that attendees arrive knowing what to expect and what is expected of them.

Factors to think about at your event

- Establish ground rules so that everyone has an equal opportunity to contribute. Chatham House rules, for example, can enable attendees to share views more freely in the knowledge that they will not be attributed back to them.

- Create opportunities for informal interaction and learning between researchers and stakeholders. Bear in mind that attendees may also want to spend some time meeting each other. You’ll need to ensure that the event timings and room layout can accommodate this.

- Ensure that you are able to capture the discussion points. If there are small table discussions, you will need a note-taker for each table. Even for plenary discussions, you may need more than one person taking notes so you can cross-check for interpretation and accuracy.

- You may want to employ a professional facilitator for large workshops or for meetings where an independent chair might help you reach consensus on important or sensitive issues.

- Circulate a brief event evaluation form, and ask attendees to complete it on the spot. Consider how you might use any learning from this to inform future events and/or provide your research project with some impact measures for your engagement activity.

- Finally, follow up with and thank those who attended, as well as those who contributed to the content. You may want to include a short report on the event. Keep in touch with the people you are likely to want to involve again.

Pitfalls to avoid

- It is easy to underestimate the resource and costs involved in coordinating events, which are often highly time- and cost-intensive. See our guide to learn about how you might secure additional support.

- It can be dispiriting if, despite all your best efforts, attendance is low on the day. If it is likely to be challenging to attract the people you want to attend, you may do better to piggyback on existing meetings/events, or to plan a series of 1:1 meetings or phone calls.

- If you are sharing information about interim findings at an event, and assuming you can trust attendees to adhere to this, you can mark this ‘not for circulation’. Do include some context about the current status of your research project – for example, if your interim findings are likely to change.

Resources

- The Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) has produced a step-by-step guide to event planning for researchers. It includes advice on choosing the venue, designing the programme and marketing the event, together with a helpful checklist for the day.

- The charity Involve offers detailed guidance on how to involve members of the public in research events and meetings.

Download this chapter as a PDF