Foreword

To those interested in policy who aren’t long in the tooth, the word ‘Wanless’ may not mean much. But it should. Named after its chair, Derek Wanless, it was a landmark review of NHS funding, published nearly two decades ago in 2002.

Why is such an old review so important to revisit? Wanless was the first serious attempt to assess objectively the long-term funding needs of the NHS. It unlocked not only unique levels of growth in funding for the NHS, but also helped justify the tax rises to pay for it. And since policymaking is mostly about human behaviour, Nick Timmins exposes how politics ‘acutely intersects’ with the issue of NHS funding to wrestle progress out of conflict (although Nick uses more vivid language). As we exit from the pandemic, these issues are even more important to understand than they were in 2002.

Three surprises

If you think of the UK NHS as one ‘industry’, it is the largest in Europe. Now in its seventies, it is also one of Europe’s oldest. Polls consistently show the NHS is a national treasure in the public’s mind, top of the list of reasons they are proud to be British, and tops priorities for extra public funding. Not surprising then that the NHS successfully extracts extra funds from the Treasury each year, to a greater extent than most other areas of the public sector. But three things are surprising.

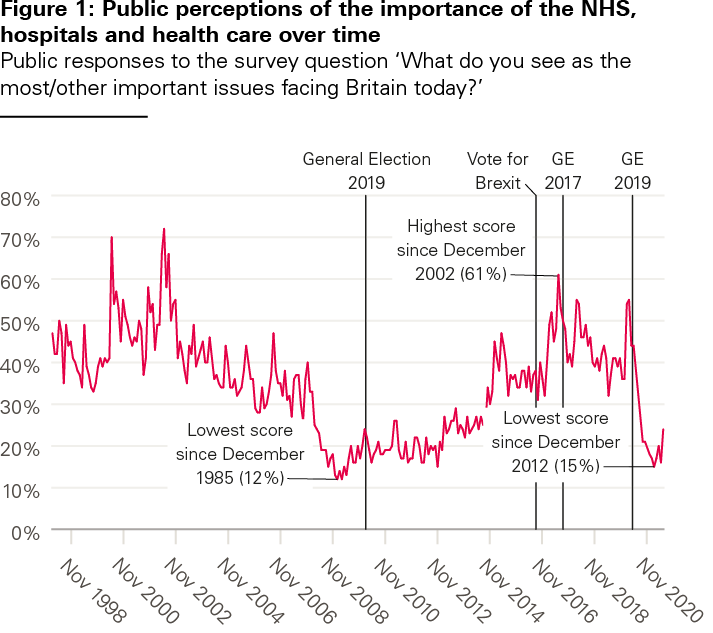

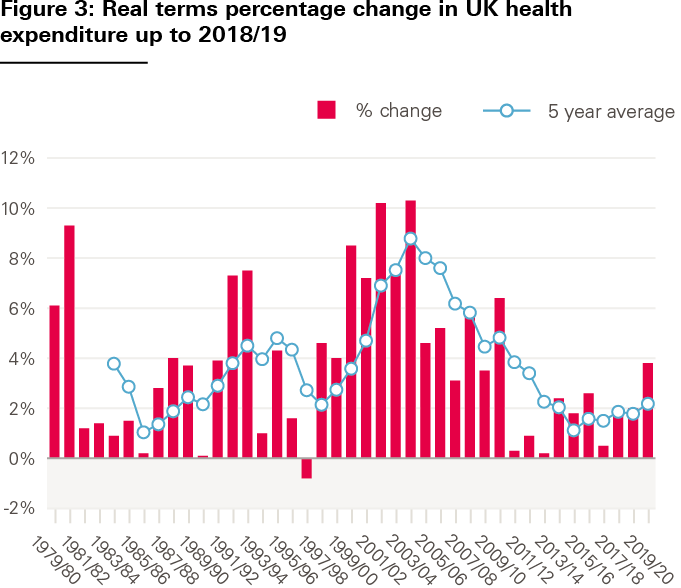

First, for such a national treasure, the year-on-year funding growth over the years has varied wildly – from 11% to -1% – making anything other than short-term planning a challenge. This matters in a service where demand for care only grows and can’t be suddenly turned off: more staff are constantly needed who take many years to train, the public expects new technologies it sees elsewhere in life, and clinical staff know that new technologies are being used to good effect in other countries, all of which need investment.

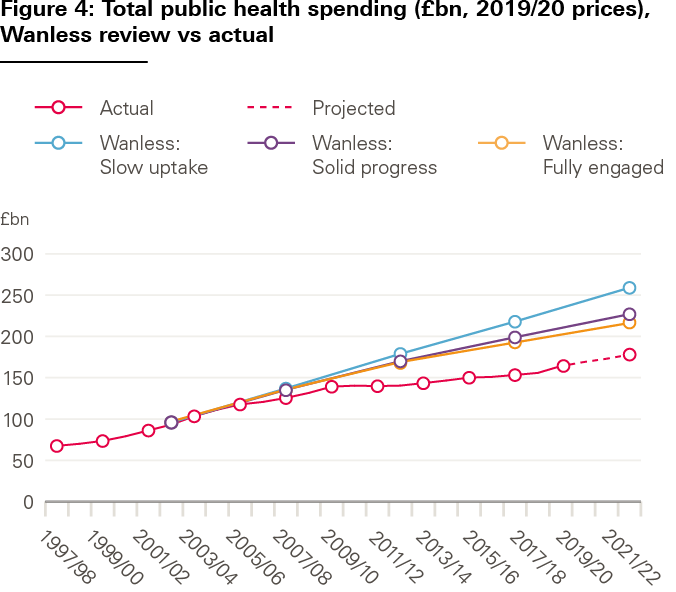

Second, other European countries have managed to invest more in health care over time – the Wanless review calculated even between 1972 and 1988 this totalled £220bn–£277bn relative to the EU average. Whatever the public and political importance of the NHS over time, paradoxically this has translated into chronic underinvestment. By 2002, this showed in a raft of unflattering international comparisons on performance, most visible in long waiting times for planned care, and winter crises in A&E.

Third, until the Wanless review in 2002, there had not been a full, objective, and published analysis of the demand pressures on the NHS under various scenarios for the long term, costed out, for the government or by the NHS itself. Wanless was a serious attempt to do that, in part made technically possible because data were increasingly available to analyse. Data, and modelling techniques, are much more sophisticated now, and yet even today there is no regular Wanless exercise for the NHS akin to the long-range projections for the economy by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Clues as to why can be gleaned from Nick’s rollicking account of the politics surrounding the conception, delivery, and outcome of the Wanless review. For sure, by 2000, recognition was overripe that the NHS needed a major slug of investment, and not only over the short term. This wasn’t just politically needed in New Labour’s first term, off the back of a decade of the NHS being ‘under attack’ by market-based ideology following introduction of the 1991 NHS reforms, and inadequate funding growth. But also because cracks in the NHS were showing, not least with ‘never never’ waiting lists, winter crises and, of course, heart-rending individual cases of lapses in care in the late1990s as Nick documents – all translated into damning headlines.

Contested origins

Absent any substantive projections as to the funding needs, in January 2000 the PM announced the European Union average (health spending as a percentage of GDP) as the target for NHS spending by 2005. The Wanless review was then commissioned by the Treasury, examining resourcing the NHS and social care, and published as Securing our future health in 2002.

Whether or not the Wanless review came about to give retrospective credibility to the PM’s target, or to give advantage in a feud between Number 10 and the Treasury, its objectivity based on evidence made the case for a substantial increase in funding, further reform and justified increased taxes to pay for it. For 5 years following Wanless, the NHS was awarded well over twice the long-run average in real-terms growth in funding. Social care received a significant boost in funding for 3 years. National insurance was raised by 1%, and this tax rise was tolerable electorally. And a day after Wanless reported, Alan Milburn (then secretary of state for health), announced not only increases in staffing and equipment, but a significant set of reforms, in part centred on reducing waiting times.

As Nick Macpherson notes, the Wanless review, ‘… led to the only serious, non-forced, discretionary tax rise since at least 1979 – and one that proved electorally appealing’. And in Ed Balls’s words, ‘When I think back on reviews I have been involved in, and I have been involved in some really good ones over the years, the Wanless review is by far the most politically significant with the longest lasting effects.’

‘Doing a Wanless’

Which still leaves the surprise that ‘doing a Wanless’ is not a regular feature of planning today. To help, in 2020 the Health Foundation launched the REAL Centre (Research and Economic Analysis for the Long Term) to provide objective projections of supply and demand, and funds needed for the NHS under different scenarios. Unlike Wanless, REAL gives full consideration of social care funding as well. And neatly, the Director of the REAL Centre, Anita Charlesworth, was the senior official at the Treasury who led the secretariat supporting Derek Wanless two decades ago.

As the UK exits the pandemic, it faces not only the backlog of unmet demand for NHS care, unreformed social care, and investment sorely needed elsewhere in the public sector. For long waiting times and winter crises not to be the norm, the political pressure for more investment in the NHS will be intense. The large debt overhang from the pandemic, and justifiable demands for investment elsewhere, will mean competition for resources will be acute as will the pressure to raise taxes.

Perhaps time then to consider another Wanless? Waiting times for elective care had steadily increased before the pandemic, and the NHS faced 100,000 in staff shortages. The pandemic has further exposed the NHS’s Achilles heel – a fundamental lack of capacity. This was also on full view with respect to shortages in staff and equipment in social care. Any review should examine not just the capacity the NHS needs to address the backlog of care, but also unmet need and inequality in access for the NHS and social care. Both are needed to build care that is more resilient to future health shocks, as COVID-19 is sadly unlikely to be the last. Such a review might give more objective credibility to assessments of how much funding is needed for care over the next 5 years; and justify that to the public, to politicians and the Treasury, especially if tax rises are on the cards.

For the NHS this time round though there is already a clear reform agenda, in the form of the NHS Long Term Plan, which commands widespread support. It will be more difficult to justify the case for further significant reform. It is the pandemic that has caused the backlog, public perceptions of how the NHS has managed the crisis and vaccine rollout, and the obvious staff commitment to duty, are favourable. And the last round of reform was costly, distracting, and of questionable impact. Instead extra resource may be better targeted directly at more basic issues that will limit progress on waiting and wider performance – such as staff shortages, insufficient technology and other equipment

For social care, the task is larger as there is currently no reform strategy, there is an urgent need for investment, and outside of a pandemic there are few screaming headlines to prompt action. It is here that political leadership, deal-making and creativity, of the sort Nick notes in this study, is sorely needed most to ‘fix social care once and for all’.

Dr Jennifer Dixon CBE

Chief Executive,

The Health Foundation

Introduction and origins

Introduction

It is almost 20 years since the Wanless report on the future funding of the NHS. As its 20th anniversary approaches, this study revisits the original – Securing our future health. It examines the origins of the Wanless review and takes something of an outline look at its methodology. It also attempts an assessment of its impact, in both the short and the long term.

The review is, however, a contested event, both in terms of its origins and its impact.

To some it is one of the most important documents in the history of the NHS, providing the massive boost in funding that hugely improved both the quality of services and access to them across the 2000s. Indeed, in some people’s eyes, it fundamentally changed the political argument over the NHS.

To others it was merely a ‘His Master’s Voice’ report, commissioned by Gordon Brown, then Chancellor, to deliver a predetermined outcome. A report to help justify what Tony Blair, the Prime Minister, had already made inevitable – a big increase in expenditure, and the associated tax rise to pay for that.

Some believe the report’s impact has been lasting. Others that rereading it is a somewhat depressing exercise. It is almost as if nothing has changed in the sense that some of its big themes – much improved health IT, far better workforce planning, better integrated care, a proper social care settlement – are still current and immensely pressing matters.

This study examines these and other issues, taking in the subsequent Wanless review of public health, while asking whether, if a government were to repeat such an exercise, there might be a way to amplify its impact.

It is important to note, however, that the government papers for this period are not yet available. So while there are plenty of references to published material, some of what is related here relies on memory, including that of the author. And honestly held memories can play tricks.

It is also worth underlining that this study does not seek to tell a full story of the management of the NHS, either at the time of Wanless or afterwards. The author has attempted that elsewhere. Some of the key events are, however, outlined because they are part of the context and helped shape the impact of the review (see also Box 1). But they are not a full account. The focus here is on the review itself.

We start with its origins … where there is more than one view of precisely how it came about.

Box 1: Timeline of the Wanless reviews and selected linked events

- May 1997: Labour landslide. Tony Blair declares at the end of the campaign, ‘We have 24 hours to save the NHS.’

- Late 1999: Gordon Brown, then Chancellor, and two key advisers, Ed Balls and Ed Miliband, devise a strategy for a long-term settlement for the NHS and the tax rise needed to deliver that. This strategy appears, however, either not to have been communicated to, or not understood by, Number 10.

- January 2000: After a winter crisis in the NHS, the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, announces on the BBC’s Breakfast with Frost that all things being equal, Labour will increase NHS spending up to the European Union average.

- March 2000: The Budget provides significant real-terms increases in NHS and social care spending, as Brown also announces he is commissioning ‘a long-term assessment of the technological, demographic and medical trends over the next two decades that will affect the health service… ’ This will become the Wanless review.

- July 2000: Following the spending rise, the NHS Plan is published, producing the first waiting time targets and the promise of more staff, more buildings and a more responsive service.

- January 2001: Anita Charlesworth appointed as the Treasury lead, with Derek Wanless subsequently recruited to head the review.

- March 2001: Wanless’s appointment is announced in the Budget.

- November 2001: Interim Wanless report.

- April 2002: Final Wanless report – Securing our future health: Taking a long-term view. Spending commitment made and national insurance increase announced. The day after, Delivering the NHS Plan announces the introduction of more market-like mechanisms into the NHS.

- April 2003: Wanless asked to conduct a follow-up review on public health.

- February 2004: Securing good health for the whole population – the public health report – published.

A more detailed timeline of NHS policies can be found at The Health Foundation’s Policy Navigator (http://navigator.health.org.uk) and at the Nuffield Trust’s NHS Reform Timeline (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/health-and-social-care-explained/nhs-reform-timeline).

Origins version one: ‘The most expensive breakfast in history’

On Sunday 16 January 2000, in what rapidly became dubbed ‘the most expensive breakfast in history’, the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, went on to the BBC’s flagship weekend political programme Breakfast with Frost. Pretty much out of the blue, Blair declared that all things being equal, the UK would increase its health spending up to the European Union average by 2005.

The commitment was enormous. Roughly 2 percentage points of GDP. And next to no one knew it was coming. Not his Chancellor, Gordon Brown, who reportedly exploded at Blair, ‘You’ve stolen my fucking budget.’ Not, in any detail, his health secretary Alan Milburn. Nor Alan Langlands, then chief executive of the NHS. Simon Stevens, Milburn’s health adviser and a future chief executive of the NHS, learned about it via a pager message while visiting a Homebase store.

Journalists like me were stunned, scrabbling to work out just what this huge commitment would cost – not least because the EU average was likely to increase over the next 5 years. It was not that different in Number 10. Robert Hill, Blair’s health adviser, put in an urgent call from his home to that of Clive Smee, the health department’s chief economist, asking him to set out precisely how much this would cost and whether it even looked achievable given reasonable assumptions around economic growth.

On a Sunday morning, outside the Treasury, Smee was the only one likely to have to hand the most up-to-date EU expenditure data on which to do the numbers. In typically self-deprecating style, in his memoir Smee recalled that most of the more complicated calculations were done by his daughter’s boyfriend because he was the only one who knew how to use the compound interest function on his calculator. The results of these calculations, which concluded that on reasonable assumptions it was in fact doable, were put out late in the day in a press release.

Over the next couple of days, Gordon Brown sought to water down Blair’s declaration from what was plainly a commitment to ‘an aspiration’. But the Prime Minister, who went on to reinforce his message at Prime Minister’s Questions, had spoken. The die had been cast. And in the March Budget, the Chancellor duly delivered the first steps on that road. He pre-empted the longer term Spending Review planned for July by announcing spending increases averaging 6.1% a year in real terms over the following 3 financial years – easily the largest ever sustained rise in NHS expenditure. The average since 1948 had been 3.3%.

These increases were historically large. But they were not on their own sufficient to raise health spending to the EU average by 2005. In the same Budget, however, Brown also announced that he was ‘commissioning a long-term assessment of the technological, demographic and medical trends over the next two decades that will affect the health service’. The review was to report to him ‘in time for the start of the next Spending Review in 2002’.

This review did not yet have a chair, nor a title. But Securing our future health, as it would become, proved to be the first serious attempt by any government in the history of the NHS to have an independent assessment made of the service’s likely future needs, and likely cost, over the next 20 years.

That account is not just the received wisdom of how the Wanless review emerged. It is the view of many of the key players involved in health financing and policy at the time, who were interviewed for this study. There is, however, another – though not incompatible – version of its origin. One that sets it in a somewhat wider context, and to which we will come (see Origins version two).

The road to Breakfast with Frost

This account opened with the statement that Blair’s announcement came ‘pretty much out of the blue’. But that is not entirely so. In fact, it had a lengthy back story. At the end of the 1990s, the NHS was in a pretty parlous state. And it is easy to forget now the extent to which the NHS model – of a tax-funded, largely free-at-the-point-of-use, and pretty comprehensive service – was itself under fire from the mid-1990s into the 2000s.

The policy and politics of the 1990s

In 1991, amid immense controversy, the Conservatives had introduced the so-called and somewhat misnamed ‘internal market’ – otherwise known as the purchaser/provider split. The ‘providers’ were NHS hospitals. These were turned into less directly managed, and somewhat more businesslike, NHS trusts. The trusts competed for patients through contracts from NHS ‘purchasers’. The ‘purchasers’ were the then health authorities and so-called GP fundholders – those GPs who volunteered to take budgets with which to buy care on their patients’ behalf. The private sector was also free to compete for these contracts, although initially that happened on a very small scale.

Many, not just on the far left, suspected that this more market-like approach, and in particular the somewhat more businesslike way of running NHS hospitals, was merely the first step towards privatising them. Furthermore, after a huge injection of cash in 1991 to make sure the new ‘internal market’ did not crash and burn on day one, money for the NHS had become increasingly tight over the 1990s. To the point that in 1996/97, the year running up to the 1997 general election, NHS spending had actually been cut in real terms for the first time since the early 1950s.

For all the diminishing amounts of growth, John Major, the Prime Minister of the day, and his successive health secretaries Virginia Bottomley and Stephen Dorrell, all supported the NHS model. As did Ken Clarke, Chancellor for most of this period, and himself the former health secretary whose white paper Working for patients had introduced the purchaser/provider split. Indeed Clarke, when asked whether he had private medical insurance, had once produced the disarming declension, ‘I don’t have it. You don’t need it. We have the National Health Service.’ But Major’s government was beleaguered throughout by the ‘No Turning Back’ group of Conservative MPs, the guardians of what they saw as the Thatcherite flame. Both they and right-wing think tanks such as the Institute for Economic Affairs and the Adam Smith Institute were, over this period, propounding various models of health care that would have diminished or removed the tax-funded, free-at-the-point-of-use nature of the NHS.

The mix of a more market-like way of managing the service through the purchaser/provider split, suspicion of where the government was taking the NHS, and ever-tightening resources saw not just the usual suspects but mainstream figures in the world of health care start to wonder whether the NHS model was, in fact, sustainable.

In September 1995, Rodney Walker, the retiring chairman of the NHS Trust Federation which at the time represented most NHS trusts, argued that rising demand, medical advances and an ageing population meant the NHS would have to be reduced to ‘a safety net’ for the old and vulnerable. Walker was a highly enthusiastic advocate for the government’s more market-like approach to running the service. Even so, his stance came as a bit of a shock.

But later the same month, a study funded by the pharmaceutical industry to the tune of £100,000 concluded that the gap between demand and resources could not be closed by taxation alone, and that user charges and ‘a clearer definition of what services will be provided free at the point of use’ were likely to be needed. It painted several not very appealing scenarios of what that might involve.

Given its funding source, that conclusion was perhaps not surprising. What was surprising was that the review was chaired by Sir Duncan Nichol, the chief executive of the NHS at the time of the 1991 reforms, and who in 1994 had shocked some by joining the board of Bupa, Britain’s biggest private health insurer, as soon as the civil service rules allowed him to do so. Leading figures on the review included Chris Ham, a Professor of Health Services Management at the University of Birmingham and a future chief executive of The King’s Fund health think tank, while its deputy chair was Patricia Hewitt, formerly press spokesperson for the Labour leader Neil Kinnock in the 1980s and who, a decade after the report, would herself be health secretary. These mainstream figures were seriously questioning whether the NHS could go on as it was – and they were not alone.

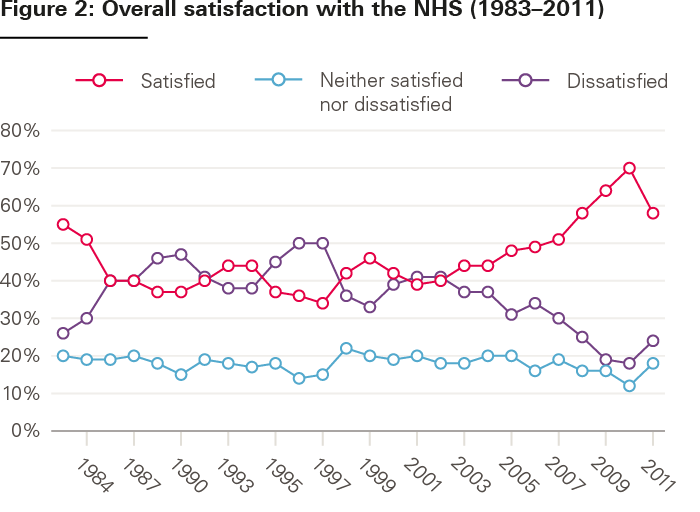

Then, in 1996, less than a year before the 1997 general election, a group of influential figures formed the Rationing Agenda Group, partly funded by The King’s Fund, and whose members included distinguished health economists, GPs, consultants and other health care luminaries, none of whom would normally be regarded as being anywhere near the far right of politics. Its conclusion was that ‘rationing in health care is inevitable’ and that the public needed to be involved in the debate about how that was to be done. Public satisfaction with the NHS had been on a downward trend in the years after 1993, to the point where according to the British Social Attitudes Survey, almost 50% were dissatisfied with it and only just over 30% were satisfied.

At one point in the midst of this Alan Langlands, the chief executive of the NHS, felt the need to go on the record to attack these ‘doom and gloom’ merchants, declaring that he wanted to distance himself from the ‘ration and privatise brigade’. The climate was such that A service with ambitions, a white paper produced by the then Conservative health secretary Stephen Dorrell, equally felt the need to open with a lengthy defence of the tax-funded nature of the NHS, arguing that the model was in fact sustainable.

In summary, during the middle of the 1990s and beyond, the NHS model was not just under attack from those who had never believed in it, but was being questioned by some who would otherwise have been seen as its natural supporters. The argument became less heated after Labour won the 1997 general election. But for reasons we shall see, Labour’s first 2 and a half years in power had not laid it to rest.

Conservative policy in early 2000

At the time of Breakfast with Frost, Conservative health policy under William Hague as leader, and Dr Liam Fox as health spokesperson, was both to promise the NHS real-terms increases – although at unspecified scale – but also to provide tax breaks for private health insurance. On the morning of Breakfast with Frost, Fox was quoted in the Sunday Times as saying that ‘philosophically’ the Conservatives had ‘moved on’ from a fully comprehensive NHS, and that ‘insurance companies could cover conditions that are not high-tech or expensive, like hip and knee replacements and hernia and cataract operations.’ The aim, the Conservatives argued, being to increase health spending overall while having a larger private sector to reduce demand on the NHS. In other words, at the time of the famous breakfast, the NHS model was still under attack from the leadership of the UK’s main opposition party.

Labour’s record before the breakfast

Alongside this ideological assault sat Labour’s record since Tony Blair’s declaration ‘We have 24 hours to save the NHS,’ made on the eve of the 1997 poll that delivered his landslide. Once in power, Labour had repeatedly talked the language not just of improvement but of public sector ‘transformation’. But in its manifesto it had also promised to stick with the spending plans of its Conservative predecessor for its first 2 years. When these plans were announced, just ahead of the election, they were so tight that Andrew Dilnot, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, suggested that Ken Clarke was ‘having a little joke’ at Labour’s expense.

The result was that money for public services, including the NHS, was seriously constrained. Thanks in part to the social security budget for once coming in some £2bn below forecast, Labour’s first big Spending Review in 1998 did deliver growth averaging 4.7% in real terms for the succeeding 3 years: above the long run average of just over 3%. Those increases, however, only started to flow in April 1999, a mere 9 months before the Breakfast with Frost. Furthermore, much of it was earmarked for centrally determined initiatives that were already under way – for example, the first walk-in centres, the creation of NHS Direct (now NHS 111), some refurbishment of A&E departments, cleaner wards, and the rebranding of the NHS so that it has a consistent logo. All but the last of these were intended to make the NHS more consumer friendly and accessible, while reducing the pressure on accident and emergency departments. But the result was the day-in-day-out services of the NHS, those in the GP’s surgery and on the wards, were still seen by clinicians to be under enormous pressure. Waiting lists were rising rather than falling – the money being so tight that Labour had had to translate an election promise to cut them by 100,000 into one that would be achieved not rapidly, but over the life of the parliament.

Back then much less data were available on NHS performance. But the state of the service can be illustrated by one reputable estimate that up to 500 cardiac patients a year were dying from their condition while on the waiting list. Over the 1990s, nurse numbers had fallen by 40,000 – a 10% reduction. In early 2000, more than 130,000 patients were waiting more than 6 months for an outpatient appointment once they had been referred by their GP. At this stage, the NHS did not even count the subsequent wait for diagnostic procedures – the scans, X-rays and tests that might well be needed at an outpatient appointment before definitive treatment was decided on.

At their worst, such waits could run to months. And once past that stage, with the patient on the inpatient list for definitive treatment, almost 70,000 were waiting more than a year. The result was that some patients were waiting more than 2 years from GP referral to treatment although the NHS had no real idea of how many, other than it was clearly many thousands, and – more likely – many, many thousands. As polling for the NHS Plan was later to underline, waiting times were the public’s number one concern about the service.

Furthermore, at the end of the 1990s, the first data on the outcomes of care internationally started to become available. On certain key aspects, these showed that the NHS was not doing well. Back in 1994 the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in one of its regular economic surveys had judged the NHS to be ‘a remarkably cost-effective institution.’ It had, since the later 1960s, spent appreciably below the EU and OECD average. By 2000, however, as the new information on outcomes became available, the OECD sharply changed its tune. It highlighted poor cancer survival rates. It suggested that other outcomes – for example for heart disease and diabetes – did not look good. It noted the apparent underinvestment in doctors and buildings. It added in the long waiting times and concluded that the NHS was probably underfunded.,,

Since its foundation, the NHS has always had a tendency to have ‘winter crises’, as do many other health care systems. But the winter of 1998/99 proved a really tough one, and in summer 1999, at its annual conference, the British Medical Association (BMA) launched a stinging attack on the government’s health priorities and its management of the service. The charge was that the government was indulging in spin over substance and had distorted priorities by rebranding the NHS and creating walk-in centres rather than getting money onto the wards and into GP surgeries. That contributed 2 days later to Blair’s famous aside about ‘the scars on my back’ from attempting to improve public services. He followed that by his party conference speech in the September about ‘the forces of conservatism’ that were holding back public service reform.

Over the same summer, Alan Langlands, the NHS chief executive, held an executive away day at which he told colleagues that things were so bad that to get the NHS back to a high quality service it needed not 4 or 5% real-terms increases but growth rates of 7 or even 8%.

In October, Frank Dobson, Labour’s health secretary since 1997, who had proved adept at extracting at least some extra cash from the Treasury in these straitened times, was persuaded – to his later regret – to leave the post to run for mayor of London. As one of his final acts he sent Blair a personal note – outside of the official channels – telling him, ‘If you want a first-class service, you are going to have to pay a first-class fare.’ While also, in Dobson’s inimitable phrasing, ‘giving him plenty of examples of things that we were crap at’. Dobson says that was ‘probably the most important thing that I did as health secretary, full stop’. A couple of years later, the Wanless review having delivered, Blair went to the trouble of sending Dobson, now a backbencher, a note saying, in Dobson’s recollection, that ‘it would not have happened, but for your note triggering it off’.

In Downing Street, Robert Hill, Blair’s health adviser, had also become convinced that the NHS needed a serious and lasting injection of funds. ‘Over the preceding 2 years I had written a series of notes pointing out the dire financial straits of the NHS. We were constantly having to shove stop-gap amounts of money in, and having fairly constant battles with the Treasury on that, including a huge row over the funding for statins when the national service framework for heart disease was introduced. They resisted that like mad. My role was to convince the PM that this was not the department doing a bleeding stump act. That there was a genuine problem here, and that we can’t go on like this.’

For these and other reasons, Blair knew that the service needed a serious injection of long-term funding, while believing in his bones that the NHS, like much of the rest of the public services, needed reform. Alan Milburn, Dobson’s successor, shared those views. If anything even more strongly.

Alan Milburn arrives

Milburn was a rising star, already tipped by some as a possible successor to Tony Blair, which did nothing to endear him to Gordon Brown, who believed he had a deal under which he would take over as Prime Minister if Labour won a second term.

Milburn had been minister of state for health between 1997 and late 1998 and closely involved in some of Labour’s lasting initiatives: the creation of what became a proper NHS inspectorate in the Commission for Health Improvement (now the Care Quality Commission) and NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). He had, however, spent the intervening 10 months as chief secretary to the Treasury, a role that had given him a good idea of what might be possible financially. Milburn was also aware of private Labour party polling showing that support for the NHS was diminishing, particularly among the young. He believed both that some pretty fundamental reform was needed in order to produce better outcomes, and to make the service less paternalistic, less institutionalised, and more consumer oriented. But he also believed that he was unlikely to get that until sufficient extra money was on the table to allow the argument with staff to be one about reform, not the shortage of money. Milburn adopted a high-risk strategy.

2 days after his return to health he told the regular dinner of the ‘top ten’ – leading figures from the medical royal colleges, the BMA and the like – that the NHS was in ‘the last chance saloon.’ If it did not modernise, he said, it would die. In public he talked up figures showing huge variations in the cost of treatment around the country, large variations in outcomes, and indeed of patients’ chances of dying in hospital, depending on where they were treated.

There was a twin-track approach here. By highlighting the service’s variations in performance, and by implicitly attacking the BMA for obstructing progress, Milburn hoped to foster a greater pace of change. But by emphasising the service’s inadequacies he hoped also to loosen the Treasury purse strings. Blair, as we have seen, had already agreed that the service needed much more money. And in the November and December of 1999, there were heavy public hints from both Blair and Milburn that more money would indeed be forthcoming.,

The problem – entirely unsurprisingly – was that the Chancellor wanted to control all of this. Whatever other ministers might think, including the Prime Minister, he regarded public spending as entirely his bailiwick. He was already working on both what the March Budget might contain, and on Labour’s second comprehensive Spending Review due for the July of 2000, which would set out the spending plans for all departments for the next 3 years.

Early in Milburn’s tenure in an, at the time, off-the-record conversation (though to be fair Milburn does not recall this), he told this reporter, ‘It’s not him I need to convince,’ – gesturing towards Brown’s Treasury – ‘It’s him,’ – gesturing towards Number 10. In his memoir, Blair says he had ‘a conversation or several’ with Brown during this period about greater spending but ‘he was fairly adamant against doing anything big’.

Winter arrives… And so does Winston

The final and perhaps decisive step in the lead-up to Breakfast with Frost was the winter of 1999/2000. A later analysis by the Department of Health was to conclude that the NHS in fact did better that year than the year before. But that was not what it felt like at the time, and certainly not what the media headlines said.

As December turned into January there was a moderate outbreak of flu, something Labour had managed to escape during its first two winters in government. It was well short of the official definition of an epidemic. But alongside it went a 15-year high in other respiratory illnesses. The result was long trolley waits in casualty, cancelled operations and a shortage of critical care beds. A consultant from the Royal London made headlines by going on television news between Christmas and January to warn that seriously ill patients were being shunted around the country to find a critical care bed, and were thus at serious risk. Alongside this was the damaging story of an Ipswich hospital hiring a freezer lorry because its mortuary was full. The most distressing story – again the subject of headlines widely– was that of Mavis Skeet, a 78-year-old woman with throat cancer, whose operation was cancelled four times in 5 weeks, to the point where it became inoperable.

The final straw was Robert Winston. An internationally regarded fertility specialist, Lord Winston was the most famous television doctor of the day. Not only was he a Labour peer, he was seen as close to the Blairs. He gave an interview to the New Statesman that made the papers the Friday before Breakfast with Frost. He relayed the experience of his 87-year-old mother on a mixed sex ward after a 13-hour wait in casualty. ‘None of her drugs were given on time, she missed meals, and was found lying on the floor when the morning staff came on… she caught an infection and now has a leg ulcer.’ That was, he said, ‘normal’ adding that ‘the terrifying thing is that we accept it.’

On top of the personal story, however, was a much broader attack on Labour’s performance and tenure. The government, he said, had been deceitful in its claims to have abolished the internal market. It was providing funding ‘not as good as Poland’s’, while it was attempting to blame everything on its Conservative predecessor. Phrases like ‘we haven’t told the truth’ littered the article. The way the NHS was funded might even have to change, he said, if Britain was to have a health care system to match that of even of its less well-off neighbours.

Combined with the other terrible headlines, this was devastating stuff. That winter was dreadful. Indeed, Milburn is on the record as saying that he might not have survived that winter had he not returned, only recently, to health having had that crucial break at the Treasury in between. By now, thanks to the service’s performance and the arguments about whether the NHS was sustainable, only three of the main national newspapers were still, in their leader columns, supporting the NHS model – as opposed to some other arrangement involving more charges, private insurance, or social insurance, or at least that a debate should be held about it.

Time for breakfast

On the Saturday 15 January 2000, according to Blair’s account of his time in office, he had already decided to make a commitment ‘to raise NHS spending to roughly the EU average.’ He says he worked through the possible permutations of what that would mean with Robert Hill, his health adviser – although Hill has no clear memory of that. ‘I talked again to Gordon,’ Blair says, ‘who became more adamant [against doing anything big]. But I was convinced, as a matter of profound political strategy, that the decision had to be taken and now.’ To signal such a commitment would have its own determinative impact, he says. He also took the view that with Milburn now at health, ‘we had a chance of getting the reform’.

So the next day Blair went on Breakfast with Frost and deliberately said it. In Blair’s words, ‘It was a straightforward pre-emption.’ And to reporters like me on the day, it was clear that it was a bounce on his Chancellor. By early afternoon it was possible to talk to Simon Stevens, Milburn’s special adviser, who had caught up with what was going on, and to Robert Hill in Downing Street who said ‘we’ll get you those figures’ as I was giving him my understanding of them. No amount of phone calls, however, managed to raise the Chancellor’s advisers. These days Ed Balls, Gordon Brown’s most senior special adviser and a future Labour Cabinet minister and shadow chancellor, agrees. ‘It did come out the blue for us [at the Treasury]’. But that leads us to the other, and not incompatible, version of the Wanless review’s origins.

Origins version two: ‘This did not happen because of one interview on the Frost programme’

Towards the end of 1999, the Treasury was already working towards the March 2000 Budget and Labour’s second comprehensive Spending Review, due in the July. Gordon Brown, Ed Balls, Ed Miliband – Brown’s other top adviser – and indeed the Treasury more broadly, knew something had to be done about the NHS.

Thinking, on a jet plane

‘We had levered some more money into the NHS in the first comprehensive Spending Review in 1998,’ Balls says. ‘But we were continually moving short-term sums of extra money in to deal with winter pressures and the like, and we needed to get something that changed the paradigm in terms of modern health spending.

‘There was more that we could do within our fiscal rules. But unless you could make the case for more taxation there was only so far that you could go. So, by the end of 1999, we felt we had got to the end of the road. If we were going to fight the [2001] election on “schools and hospitals first”, which was our plan, we did not feel as though a 3-year settlement for health in the 2000 Spending Review would be enough. We needed a paradigm shift. And our view was that you had to make the case for the need before you could go on to the argument about tax.

‘So what we needed was a long-term vision of the sort of health service we wanted, and fight the election with that plan. But have a financing review which has not yet reported, but will report after the election. And then after the election you say, “We have a mandate from the election to deliver our 10-year plan, and the financing report, which was in our manifesto, says this is what is needed…”, and therefore we get on and do it.

‘So, at the end of 1999, Ed [Miliband] and I were flying out to New York for an international meeting and talked all this through before we met Gordon and Bob Shrum [the long-time Democrat political consultant]. We came up with a twin-track approach. Which was first to push the perspective about the National Health Service into a longer time frame, and then to start a pre-election debate about the funding of the National Health Service – one which could figure in the manifesto for the general election, but which would not be concluded until we had a mandate to deliver that manifesto in the second term.’

It was tax, not just spend

As far as Ed Balls is concerned, that was the origin of the Wanless report. A report that would make the case for much more generous funding for the NHS and which would, in turn, justify the tax increase needed to achieve it. And that too is the view of Ed Miliband, Brown’s other key adviser and future Labour party leader. Miliband also – quite independently – remembers that long plane journey and the lengthy discussion ‘about how do you argue for the proper financing of the health service?’

‘And I remember Gordon saying, “You can’t just come out of the middle of nowhere and say this is what we are going to do. You have to methodically go out there and make the case for it.” We needed a review.’

Wanless, Miliband says, ‘certainly did not happen just because of one interview on the Frost programme. For the Treasury to be volunteering to spend a lot of money on the health service is quite an unusual thing. But that was the case. It was long planned in the sense of making this argument about financing the health service properly, and then raising the taxation needed for that to happen.’

Nick Macpherson, the Treasury’s director for public services at the time and later its permanent secretary, confirms that by the end of the 1990s the Treasury was well aware that the NHS needed more money, but was also thinking about how to raise the revenue to pay for it. There had been some growth in NHS expenditure since Labour took power, Macpherson says, ‘But I think it is fair to say that the outputs of the service were not consistent with the vision of a New Labour government, elected with a huge majority, which was promising not just to change public services but to transform them.’

In the late 1990s there had been a big surge in revenue. ‘But by the early 2000s the days when we were awash with tax revenues were beginning to recede. So if you were going to give the NHS more resources over the medium term, which I think everyone agreed was almost certainly necessary, you needed to get public opinion on side.

‘So, from a Chancellorial and Treasury point of view this wasn’t simply about announcing spending increases. It was also about trying to create a bit of a public debate to facilitate serious revenue measures that would help finance the health service in the medium to long term. Like a lot of the reviews that Mr Brown had commissioned, and there had been quite a few of them by then, the review process was designed to try to create an emerging consensus.’

By 2001, Macpherson says, Milburn and Blair were developing much more of a reform agenda for the NHS, ‘But I don’t think the Blair gang ever really got their head around the revenue which would be necessary to finance it. So that was part of the thinking underpinning Wanless.’

Love’s Labour’s Lost: Number 11, Number 10 and the Department of Health

The Treasury was, of course, interested not just in more money for the NHS but in the modernisation of its operations to provide better and more productive services. And in the Blair government, there was, of course, the second power base in Gordon Brown’s Treasury, which had already introduced hundreds of targets for public service improvements through detailed departmental public service agreements, including for health. At the same time, Blair, as we already have seen, was deeply committed to public sector reform in general, and of the NHS in particular.

One factor in this, Balls says, was the Treasury’s relationship with health. ‘With some departments, our relationship was very bilateral. With trade and industry, for example, and with the regions and transport. In the case of education, Tony had things he cared about and Gordon had things he cared about, and Gordon always had a good relationship with Blunkett [David Blunkett, Labour’s first education secretary]. Whereas with health, from a policy point of view, the health department was really run from Number 10. We’d discuss things with Jeremy Heywood [the Prime Minister’s principal private secretary and future Cabinet secretary] and Robert Hill [Blair’s health adviser], and we would have left it to Hill to sort the department out.’ Which is also a polite way of saying that Alan Milburn and Gordon Brown were not exactly soulmates.

‘We were in this conversation with Number 10 about all this already. We were wanting to focus on what kind of long-term health service are we trying to achieve? What goals do we want to achieve? What outcomes do we need? And how do we get the financing to do it? And Tony knew that is what we wanted to do. It was what he wanted to do.

‘And then suddenly, out of the blue, on the Frost programme, he says this thing about getting us up to the EU share.’

Ed Balls’s theory is that Robert Hill had written Blair a policy note saying, ‘We really should be ambitious in going for the EU share of GDP.’ ‘Tony reads it and goes on the Frost programme and says it. And maybe he said it because he wanted to be on the lead on health for the Budget, and maybe it was just in his head and he said it… and who cares?’

Hill is not entirely sure about that, and the government papers that would make it clear are not yet available. Hill says: ‘I was asked to write a note ahead of the interview, but I wasn’t really given the context, and I was not privy to the way the Prime Minister’s mind was working. I had previously briefed the PM on the percentage of GDP that various European nations were spending on health. But my recollection is that this was more in the context of bolstering the case for upping our game on health spending, rather than understanding that we were specifically considering going for the EU average. I genuinely can’t remember whether I put the EU figures in the note ahead of the Frost programme. Certainly there was no modelling.

‘When he said it, I was surprised by the precision of the commitment. I certainly wasn’t sitting there thinking Oh, right he has said it – good. Tick. If I was expecting anything, it was that he might commit a Labour government to more substantial real-terms increases in NHS spending year on year. If I’d been expecting the commitment to the EU average, I wouldn’t have needed to put that call in to Clive Smee.’

Furthermore, in sharp contrast to Ed Balls’s recollection, Hills says he was unaware of the Treasury game plan that became the Wanless report, it becoming clear only after Breakfast with Frost with ‘the Treasury becoming more open about the Wanless project’.

What is clear is that, in Ed Balls’s words, Blair’s announcement was both annoying and frustrating. ‘Gordon was grumpy about it: “Why is he doing it on the Frost programme when we are trying to do it in the Budget?”.’

‘The reason we were frustrated was twofold. One, he made the measure of success the input, not the output. And our whole strategy was to have the money following the goal. The goal should be about the ambition of our health agenda, and there is nothing galvanising or dynamic about the EU share of GDP. It is an input. It doesn’t say anything about why, or how well it is spent.

‘And secondly, we always knew that to win this argument, we had to put in place the reforms and accountability which would persuade people that the money would be well spent – and the problem with that announcement was it was not really attached to any reform. In that sense it was a bit old fashioned. Let us set an input spending target rather than focus on the outcomes you wanted to get for that. So it was a bit jarring for our political strategy. But you know – on the balance of this – while we were annoyed about it, we then thought fine. This was going to help shake things up. He was throwing health into a longer term perspective. So it was consistent with everything we were trying to do.

‘But I would have had some slightly difficult conversations with Jeremy [Heywood] about why is he doing this? Why didn’t we talk about this in advance? Why was there not a bit more conditionality?’

And, Balls says, it was unusual. Despite what their staff dubbed ‘the TB/GBs’, ‘for all that is said about Blair and Brown, we very rarely surprised each other. There was genuinely a conversation about how things were to be done. If there was a disagreement it was normally resolved before things went out. A bit of give here, or a bit of give there. There was not normally ‘out of the blue’. Tony rarely saw Gordon interviews and thought Oh God, why has he said that? – or vice versa.’

Alignment at last

What immediately followed Breakfast with Frost, according to Blair, was ‘a few days of tin-helmet time with Gordon’ but the announcement ‘allowed me to get on with the other part of the plan: to work with Alan on a serious proposal of reform’.

What eventually emerged, to go with the March Budget, was a formal statement from Blair the day afterwards. It announced work on a multi-year plan for modernisation and reform of the NHS.

Ed Balls says the Treasury team pressed hard for that. ‘We needed something that showed we had ambitions which went beyond the 2000 Spending Review, and it needed to be big and significant, so the PM agreed to do the statement on the 10-year plan the day afterwards.’ The Prime Minister fronting the statement, with the Chancellor sitting ostentatiously alongside him, was ‘symbolic and important’, Balls says, underlining the scale of the ambition.

In the wake of Breakfast with Frost, however, some commentators viewed that announcement much more cynically. Brown had found the money, or at least the first tranche of it, but Blair was in charge of spending it. If the project failed, Brown would know, and would make sure that everybody else knew who was to blame.

In his statement Blair spelled out the manifold challenges that the NHS faced, promising action. He invited the BMA, the royal colleges, the unions and others to help devise by July ‘a detailed 4-year action plan for the NHS’. That did indeed become the ‘big tent’ operation that produced the NHS Plan, subtitled A plan for investment. A plan for reform – although by then it had morphed into a 10-year plan. Its promises included a more responsive service and more of pretty much everything – staff, equipment, hospitals, students – while setting Labour’s first targets for cutting waiting times. It also announced a new ‘concordat’ with the private sector, without that new relationship being very precisely defined. And, of course, in the Budget the Chancellor had announced the as yet unnamed Wanless review.

Blair and Brown were now, at least temporarily, aligned. The strategy that would lead to the tax increase necessary to hugely improve the NHS, and increase health expenditure up to the EU average, was in place.

* See, for example: Glaziers and window breakers: former health secretaries in their own words. 2nd edn. The Health Foundation, 2020 (https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2020-C03); Never again? The story of the Health and Social Care Act 2012, 2012; ‘The world’s biggest quango’: The first five years of NHS England, 2018 (both Institute for Government and The King’s Fund); and finally, The five giants: A biography of the welfare state, William Collins, 2017.

† At the time I was public policy editor at the Financial Times.

‡ The only remotely comparable independent exercise was the Guillebaud report of 1956. Set up by the Treasury in the hope it would recommend cost constraints at a time when NHS expenditure appeared to be out of control, the report concluded that to be anything but the case. Instead, it made recommendations that ‘will tend to increase the future cost’. Unlike Wanless, however, it did not make long-term projections of likely future costs.

§ ‘Internal market’ was always a misnomer. In theory, and indeed at the time in practice, the private sector competed for NHS contracts although to a very limited extent.

¶ Known in the jargon as a ‘quasi-market’ because, while it had elements akin to a private sector market, patients – of course – did not themselves pay.

** I remember declining to take part in a BBC programme whose thesis was that privatisation of NHS trusts was inevitable. My view was that it was possible, but not inevitable.

†† Seven out of ten felt waiting times were too long in polling for the NHS Plan. See Annex 1, The NHS Plan. Department of Health; 2000 (http://1nj5ms2lli5hdggbe3mm7ms5.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/files/2010/03/pnsuk1.pdf).

‡‡ For example, Blair had already set up a cancer action taskforce. See: https://reader.health.org.uk/unfinished-business/timeline

§§ Labour had abolished GP fundholding, but not the purchaser/provider split. Health authorities had morphed into Primary Care Trusts which continued to commission care from nominally competing NHS trusts and the private sector, even though they had had a duty of cooperation placed on them.

¶¶ The three were The Guardian, the Daily Mirror and the Financial Times.

*** The fiscal rules were that Labour would borrow only for capital investment, financing current expenditure out of tax and other revenues. And that it would keep public sector debt at a ‘stable and prudent level’, which it defined as less than 40% of GDP. Both rules applied on average over the economic cycle, rather than having to be met each and every year.

††† This chimes with Gordon Brown’s account in his memoir My life, our times. Vintage; 2017 (p 163).

‡‡‡ Gordon Brown, in his memoir, ibid, (p 164) says that, ‘Tony had announced the gain – the spending increase – without announcing the pain – the tax rise.’

§§§ One other exception was Blair’s announcement in March 1999 that the government intended to abolish child poverty over 20 years.

The Wanless review and reports

Getting going

The chair and terms of reference

The Treasury lead for the Wanless review was Anita Charlesworth, deputy director of public spending at the time. It was not until January 2001, almost a year after Breakfast with Frost, that Charlesworth was appointed and substantive work started. As a result the review was conducted under appreciable time pressure.

‘The first I heard of it,’ Anita Charlesworth says, ‘is when Nick Macpherson came to me and said, “They want to do a review of NHS funding, would you lead it?” And I said “Well, there is no way of doing it that will not come up with a huge number. And I don’t want to do something like that for a year and more and then you have to bury it because no one likes the answer. So are they really up for that?”

‘So he said, “Go and see Ed Balls.” And it was clear that actually they were up for it, and they did understand that this was going to be a very large number.’

Furthermore, ‘It was clear that they were interested in other issues beyond the politically important one of waiting times. Issues such as outcomes. And that was to Treasury ministers’ credit. You might say, well once you’ve set the target of getting to the European average, why would you bother doing this?

‘But people did want to think more fundamentally. Part of that was Gordon Brown’s view that if you are going to start to spend – and he clearly wanted to spend – they had to be seen not just to be spenders. The ‘something for something’ agenda, the ‘rights and responsibilities’ agenda, the ‘prudence with a purpose’ agenda. All of that was deeply felt. Deeply felt by him personally, but also felt by him to be incredibly important for a Labour government that was going to start to spend. He felt that had to be handled really carefully.

‘So he really did want to be very clear about what you were going to get for the money, and how that would deliver both substantive improvements but also a more efficient system. There was a very strong desire to tilt the focus of the system towards not just access issues but outcomes. And I certainly felt it was a worthwhile endeavour to be doing, for those reasons.’

Two of the most important questions to settle were the terms of reference and the chair. The terms of reference reflected those in the Chancellor’s Budget statement and amplified them. Namely:

- To examine the technological, demographic and medical trends over the next two decades that may affect the health service in the UK as a whole.

- In the light of (1), to identify the key factors which will determine the financial and other resources required to ensure that the NHS can provide a publicly funded, comprehensive, high-quality service on the basis of clinical need and not the ability to pay.

- To report to the Chancellor by April 2002, to allow him to consider the possible implications of this analysis for the government’s wider fiscal and economic strategies in the medium term; and to inform discussions in the next Spending Review in 2002.

The devolved administrations – Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – were to be involved.

The terms of reference did three things. First, they made it clear that the NHS model was not in question. Second, it did not need much reading between the lines of point three to see that this might be used to justify tax increases. And third – by being silent on the issue – this review was not going to look at the management and organisation of the NHS. That was going to remain Milburn and Blair’s jealously guarded territory – via the NHS Plan and what followed from that.

Who was to chair it? Discussions were held with two people. Adair Turner, the former director general of the Confederation of British Industry, and Derek Wanless, who had recently ceased to be the group chief executive of NatWest. Wanless was a member of the Statistics Commission, a body that Gordon Brown and the Treasury had just created and which had brought the two into contact. As Ed Balls puts it: ‘We wanted it to be somebody who would be a credible person talking about the money and the finances, and productivity and value for money. But also someone who was a believer in the National Health Service.’

At this time, well before the financial crash of 2008, New Labour in general, and Gordon Brown in particular, had a distinct fondness for using bankers and business people as outside chairs for the huge range of external reviews, or external advisory bodies, set up in Labour’s early years. Part of its ‘big tent’ approach to politics.

Thus, to take just two examples from the many, Martin Taylor, the chief executive of Barclays, had chaired a task force on work incentives looking at social security benefits, tax and national insurance and that had recommended the introduction of tax credits. Sir Colin Marshall, the chairman of British Airways, had a look at industrial energy use, a report that led to the climate change levy. Both policies that Gordon Brown wanted to adopt, but using, as with Wanless, an external imprimatur to help make the case for the change.

Adair Turner fell out of the running because he wanted not just to look at likely trends and demands over the next couple of decades, but to ask the question about whether a tax-funded NHS was the right model. It is all but certain, from his other writings and pronouncements, that Turner would have concluded in its favour, at least in the medium term. But he was not prepared to undertake the review without asking the question.

But as Balls says: ‘The reality is that this was a Labour government committed to a National Health Service in the public sector, based on need not ability to pay and free at the point of use. So we were not looking for someone who was going to come along and go back to first principles. This was not about the financing of UK health care, it was about the financing of the NHS into the future… we were not going to ask an unelected Adair Turner, former head of the CBI, to do a review into whether the basis of the Labour party manifesto of 1997 was correct.’ That conversation therefore ended, though amicably enough.

Instead the task went to Derek Wanless who was happy with the constraint on the terms of reference. Although, as we shall see, the question of alternative funding mechanisms did eventually surface in the interim report.

Style and methodology

Anita Charlesworth says: ‘Derek was no socialist. He was a banker. But he did believe in public services in general, and the NHS in particular. And that was important for people in the NHS. I think for everybody who met him through the process, many started with a fair degree of scepticism about a banker. But he did, I think, win everybody over. People had confidence in him. And that was really important.

‘Furthermore, he was a statistician by background and that was also important. He was very analytical. It was always clear that this was aimed at the 2002 Budget. So we did not have very much time to do this, and you needed someone who gets the hang of the numbers very quickly. So his background in statistics helped a lot. He was very numerate.

‘The doctors and the analysts liked him because he was a technocrat in many ways. He listened to evidence and he liked evidence. So he got a lot of cooperation and collaboration. And, of course, canny people recognised the massive opportunity that this offered. It was also important that he was from Newcastle.

‘Obviously, Alan Milburn was not entirely happy about this process. I had to sit in a meeting where Alan Milburn and Derek Wanless met each other, talked about the football club, and established that Derek was OK. It also established that Derek would deal with the funding and would not look at how the NHS was run. And that was very much Milburn’s stipulation. He was not having the Treasury telling him how to run the NHS.

‘What I’ve said may imply that Derek was up for being pushed around. He wasn’t at all. He was very clear at the beginning that it would be his answer to this question, and that it would be published regardless. He made that absolutely clear. And he was later to stretch his terms of reference by at least taking a look at social care.’

The Wanless review may have been born out of deep internal tensions within the Labour government. But once the terms of reference had been agreed and the team appointed, it was all pretty much sweetness and light.

The Treasury team was assembled and to it Steve Dunn was seconded, an economist by background and a member of the Department of Health’s recently formed strategy unit. Dunn had in turn been placed into the unit by Clive Smee, who wanted to know what it was up to. ‘I was, so to speak, Clive’s mole in the strategy unit – but they knew that,’ Steve Dunn says. During the Wanless review Dunn played a similar mole-like role, that was similarly recognised. He reported back into the strategy unit as he spent 4 days a week in the Treasury, and a day back in the department.

There was, however, no real tension. Anita Charlesworth says that Smee and his team were ‘absolutely critical’ with Robert Anderson and John Henderson, two senior economic analysts in Smee’s team, doing a lot of the work. It also helped that Charlesworth had previously worked for Smee and knew many in the team.

If you were to carry out the Wanless exercise today, Charlesworth says, ‘There is a lot of data that is now routinely published that you could use.’ But back then there was less information and even less of it was routinely published. ‘So the technical task of doing the review required a very great deal of cooperation and support from the system, particularly from the public health community, the stats community, the economists, etc. And most of those worked in the Department of Health, getting the data and getting it organised so that we could use it. Without serious cooperation, support and collaboration, we would have been sunk.’

The review originally intended to build up the profile of NHS costs disease by disease, but there were insufficient data to do that. What came to the rescue – and proved in many ways to be the technical backbone of the report – were the National Service Frameworks. These documents, originally commissioned in Frank Dobson’s time as health secretary, set out the standards of care for particular disease areas, pointing to the most effective treatments both clinically and in terms of value for money, while suggesting the best way to organise services. Detailed costings had gone into them, not least to help persuade the Treasury to provide funding. As Wanless was getting going, these covered only coronary heart disease, cancer, renal disease, diabetes and one being developed for mental health. Between them, the five covered only around 10% of NHS expenditure. But between them they also accounted for about 50% of all mortality and some 12% of morbidity.

‘A huge amount of work had been done to build and cost those,’ Charlesworth says, ‘and I think Clive, in the nicest possible way, added a huge amount to their cost for the purposes of the Wanless review. Some of the costings proved reasonably flexible … and we could not have done that depth of work in the time available.

‘Furthermore, a lot of people in the department had worked on those. They were also clinically led, so in developing them the department had built a network of clinical engagement and consensus involving all sorts of people, including the royal colleges, and we were able to build off that.’

The review also created an external advisory group that helped identify what data were more than likely available if you knew what to ask for. As Charlesworth puts it: ‘You can’t always ask for what you don’t know about. And sometimes these sorts of review can struggle because if people have not produced things in the way you need them, you may not know that can in fact be done. So we used the advisory group to be able to get at those sorts of things officially.’

The review held three workshops, one each hosted by the Nuffield Trust, The King’s Fund and the Association of British Pharmaceutical Industries, with similar events in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast to ensure engagement across the UK. It visited the United States and Australia, the latter including discussions with delegates from New Zealand. And in October 2001 it held a wider 1-day conference, just before publication of the interim report in November, to which selected media were invited.

And across the whole exercise there was a cross-departmental steering group of civil servants, chaired by Nick Macpherson, whose membership included Nigel Crisp, the NHS chief executive and permanent secretary at the Department of Health, and Liam Donaldson, the chief medical officer. ‘This was not one of those reviews that was done in secret,’ Nick Macpherson says. ‘It was all pretty transparent, and the cross-Whitehall group allowed everybody to feel they knew what was going on, and they could report back to ministers if they had problems. But I don’t recall any.’

Box 2: Summary of the interim report, November 2001

The interim report opened with two core questions. ‘What are people likely to want [from the NHS] in 20 years’ time? And what resources likely are required to deliver the service?’ It underlined that this was ‘the first time in the history of the NHS that such a long-term assessment of resource needs has been attempted’ – while acknowledging that looking so far ahead ‘is fraught with difficulty’.

It set out funding over the 40 previous years, during which annual increases had see-sawed between +11% and -1% in real terms, noting that ‘this variability can only have added to the difficulty of managing the service effectively and efficiently’. The report then took what looked to be a carefully selected group of comparator countries against which to benchmark the NHS’s performance – France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, along with Australia, Canada and New Zealand. These countries were chosen, the report says, for having similar aspirations to high quality and comprehensive care, while having incomes per head that were broadly similar. The comparison, across a range of measures, painted a generally unhappy picture. Survival rates for cancer lagged well behind European comparators, for example. More children died in the first year of life than in any of the comparator countries other than New Zealand. Health outcomes generally were poor. Waiting times for treatment were long.

But it then set out what was arguably the killer fact in either the interim or the final report. Namely, a widening gap had developed between UK health spending as a share of GDP and the average spent in the EU. Over the 16 years between 1972 and 1988, the cumulative underspend compared with the EU average was between £220bn and £267bn, depending on whether an income-weighted or unweighted average was used. ‘Not surprisingly, with such significantly lower spending, UK health service outcomes have lagged behind continental European performance.’ Very drily, it noted that ‘the surprise may be that the gap in many measured outcomes is not bigger, given the size of the cumulative spending gap’ (p 37).

The interim report did look at funding mechanisms, concluding, unsurprisingly given the terms of reference, that general taxation held up well against the alternatives. ‘There is no evidence that any alternative financing method to the UK’s would deliver a given quality of health care at a lower cost to the economy. Indeed other systems seem likely to prove more costly.’ (para 2.21).

It discussed the methodology for estimating the future demand for resources, saying that ideally they would be built bottom-up on a disease-by-disease basis. But that was only possible in the limited areas where the government had started to create the already mentioned National Service Frameworks for specific conditions. In the absence of better disease data, it took a life course approach, using a mix of demographic data and figures showing that average annual expenditure varied by age from around £2,000 per head for births and for those aged 85 and older, to a couple of hundred pounds a head on average for those aged 5–15 (p 15).

It acknowledged that patient expectations would rise, with future patients likely to be better educated, more affluent, less deferential and wanting more choice. They would also want better integrated care, much shorter waiting times, and improved accommodation – ‘not The Ritz, but not the YMCA’. And it set out a series of questions for consultation around all these issues, to help inform the final report.

The interim report also noted, accurately, ‘Trying to look ahead over such a long period of time is fraught with difficulties. The uncertainties are huge.’ By way of illustration, the report expressed concern about a shortage of cardiac surgeons, but, entirely understandably, failed to spot the rapid rise that was on its way in interventional radiology, which has meant that procedures, such as revascularisation, could be carried out by others. Equally, the section on delivering quality mental health care considers drug costs but failed to foresee the rise in the use of CBT and other talking therapies that was to come within the next 5 or so years.

The interim report

The interim report ploughed the ground and sowed the seeds for the final report to come. It laid out the core arguments about resourcing, including comparisons with other countries’ spending and set out the review’s methodology. But it did so without yet putting any numbers on the increases it was to recommend in the final report.

It contained one surprise, given the original debate with Adair Turner over its terms of reference. The report noted that it was set up to examine the resources required to run the health service in 20 years’ time – and that it was ‘not set up to examine the way in which those resources are financed’.

Nonetheless, its fourth chapter did examine alternative funding mechanisms, including social insurance, out-of-pocket payments and private insurance, and how those were used in the countries that it had chosen for comparison. Entirely unsurprisingly, it concluded that the UK’s model of general taxation held up well. ‘There is no evidence,’ it said, ‘that any alternative financing method to the UK’s would deliver a given quality of health care at a lower cost to the economy. Indeed other systems seem likely to prove more costly.’

Anita Charlesworth’s recollection is that it was Ed Balls who instigated the financing section. ‘We had not set ourselves up to look at alternative financing methods. It was not in the brief, and it was pretty much excluded by the terms of reference. Indeed, I had spent a lot of time explaining to those we talked to that it was outside the brief. And then suddenly it was in. So we had to do this very rapidly. And it shows, I think, in the interim report.’

Balls confirms that the decision to put in a section on funding models came from him. ‘The Conservative Party’s line at the time was to paint the NHS as a failed model,’ he says. ‘And I remember a discussion with the editorial people at The Times as the interim report was being done and them wanting to have a discussion about whether the Wanless report was ducking the big issue – which was whether a tax-funded NHS was the right model. So what became clear is that while our focus was on matching reforms with resource to deliver a 21st century National Health Service, there was a prior argument to be fought about whether the NHS was the right model.

‘It was never Wanless’s job to do that. It was our job, and the Conservatives were seeking to open up that dividing line. So I said to Anita that the interim report will be the platform on which we will have to go out and win arguments between now and the Budget. I know that the whole terms of reference are about a free-at-the-point-of-use, tax-funded health service. That is our starting point, and we are not asking Derek to examine that. But if there is nothing at all in the report about that issue, and why that is our starting point, it is going to look pretty weird. So would Derek be happy in having a short discussion in the report about why this is the starting point in the terms of reference? And that was what went in.’

With a bit of a blip: ‘I have not sought to bury anything’

The inclusion of a section on alternative funding mechanisms led to a bit of a blip when the interim report was published, alongside the pre-Budget report in November 2001.

Gordon Brown, in his speech, underlined the Wanless conclusion that, ‘There is no evidence that any alternative financing method to the UK’s would deliver a given quality of health care at a lower cost to the economy. Indeed other systems seem likely to prove more costly. Nor do alternative balances of funding appear to offer scope to increase equity.’ Michael Howard, the Conservative shadow chancellor, dismissed the report in general and that finding in particular.

Given that the terms of reference were ‘… to consider a health service that was exclusively publicly funded,’ Howard said, ‘it should not surprise anyone that Mr Wanless came up with the answer that the Chancellor wanted him to find; that a publicly funded service would be better. If you ask a Labour question, you get a Labour answer.’ He added that it was ‘now clear to everyone except Gordon Brown that without fundamental reform of health care, more money will not deliver the results which people in this country are entitled to expect’.

The ‘Labour answers to Labour questions’ jibe appeared to sting. And at a press conference called 2 days later to promote the report more generally, Wanless, when challenged on the alternative funding issues, stood by his conclusion that the NHS was underfunded. And that if equity was important to the British people then a tax-funded system was the most fair and efficient way of doing it. But, he said, it was ‘not his job’ to bury alternative funding models. He promised to talk to the Association of British Insurers further about their role, adding: ‘I have not sought to bury anything for good. It would be quite presumptuous and premature to do that.’

Anita Charlesworth’s explanation is that the funding section went in late. ‘So we did not go through a big process where we exposed him to lots of views, and gave him time, and built a roundtable – with time to think about it [the issue of alternative funding mechanisms]. So it came in quite late, and I think he was still cogitating, rather unhelpfully, when the interim report came out.’ The Conservatives sought to make capital, but Wanless’s ‘it’s not my job to bury anything’ proved to be only a 1 or 2 day wonder.

That did not mean that the media reaction to the interim report was a universal welcome. Anything but. It was not just the right-wing press, for example the Daily Telegraph, which accused both Wanless and the Chancellor of closing down the argument that the NHS should continue ‘as a publicly funded monolith’. The Independent said that ‘… those with more open minds will want to consider in more depth the evidence against alternative funding methods’. Anthony Browne, The Observer’s health editor, declared: ‘Whether it is paid for by tax or by other forms such as social insurance is the subject of a national debate that Gordon Brown said we must have. We do need this debate, yet Brown also declared the answer: more tax is the only way to pay for the NHS.’