Acknowledgements

The Health Foundation commissioned the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA) and Demos Helsinki to conduct domestic and international case studies.

The authors are grateful to everyone who offered their time and expertise to organise or take part in interviews and site visits in Leeds, Plymouth and Glasgow, as well as New Zealand, Finland, Sweden, the US and Germany.

We are also very grateful to members of the project advisory group for their invaluable support and challenge throughout: Jussi Ahokas, Dr Richard Crisp, Professor Anne Green, Alan Higgins, Professor Heikki Hiilamo, Professor David Hunter, Chris James and Neil Lee.

We would also like to thank Lisa Gibson, Emily Collacott, Ed Cox, Philipa Duthie, Jamie Cooke, Miriam Brooks, David Finch, Professor Dominic Harrison, Jenny Cockin, Sean Agass and many other colleagues who have made this report possible.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL:https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2020-HL07

Written by

Yannish Naik, Isabel Abbs, Tim Elwell-Sutton, Jo Bibby and Emma Spencelayh (The Health Foundation)

Atif Shafique, Ian Burbidge and Becca Antink (RSA)

Leena Alanko and Johannes Anttila (Demos Helsinki)

RSA

The RSA (royal society for arts, manufactures and commerce) is committed to a future that works for everyone. A future where we can all participate in its creation.

The RSA has been at the forefront of significant social impact for over 260 years. Its proven change process, rigorous research, innovative ideas platforms and diverse global community of over 30,000 problem-solvers, deliver solutions for lasting change.

The RSA invites you to be part of this change and join its community. Together, we’ll unite people and ideas to resolve the challenges of our time.

Find out more at www.thersa.org

About Demos Helsinki

Demos Helsinki is a globally operating, independent think tank that conducts research, practices consultancy, and runs the UNTITLED initiative.

The Demos ethos is: "Only #together can we fight for a fair, sustainable, and joyful next era".

Demos Helsinki works with curious governments, cities, companies, universities, and other partners who aim to make an impact on ongoing societal transformations. Demos are 50 kind individuals from diverse backgrounds, based in Helsinki and Paris.

Find out more at www.demoshelsinki.fi/en and https://untitled.community

Glossary

Anchor institution: A large organisation with significant assets and resources that can be channelled in different ways to support community regeneration. Such organisations are called ‘anchors’ because they are unlikely to move – they are rooted in place.

Degrowth: The idea that economic growth is not compatible with environmental sustainability and that decreasing resource consumption is required to achieve human wellbeing in the long term.

Economic development: Proactive approaches to shaping economic progress. Local economic development activities in the UK are often carried out by organisations such as local authorities or local enterprise partnerships.

Economic growth: Increases in GDP over time. There is an association between GDP and health outcomes, though the relationship between them is complex.

Green growth: Economic growth and development which is environmentally sustainable and creates the conditions that are good for people’s health.

Gross domestic product (GDP): The market value of goods and services produced by a country in a particular time period; often used as a major indicator of economic performance and success.

Gross value added (GVA): A regional indicator used to measure added value. GVA is not directly translatable to GDP or productivity.

Health inequalities: The difference in health outcomes across population groups, often due to differences in social, economic, environmental or commercial factors.

Inclusive economy: An economy in which there are opportunities for all and prosperity is widely shared.

Inclusive growth: A way of thinking about and pursuing economic development that emphasises the importance of giving everyone in society a stake in economic growth by ensuring its benefits are fairly distributed.

Industrial strategy: A collection of economic policies that a national, regional or local authority commits to pursuing, which aims to achieve objectives that may not only be economic.

Local enterprise partnerships: Organisations in England made up of local authorities and businesses that promote local economic development.

Postgrowth: Moving beyond a focus purely on economic growth to pursue sustainable human wellbeing.

Wider determinants of health: The social, cultural, political, economic, commercial and environmental factors that shape the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. They may be called 'structural' or 'upstream' factors.

Executive summary

This report sets out how economic development can be used to improve people’s health and reduce health inequalities in the UK. Its lessons are timely and relevant, with the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic showing us that people’s health and the economy cannot be viewed independently. Both are necessary foundations of a flourishing and prosperous society.

Health inequalities are growing in the UK. Since 2010, life expectancy improvements have slowed and people can expect to spend more of their lives in poor health. How healthy a population is depends on more than the health care services available to them – it is shaped by the social, economic, commercial and environmental conditions in which people live. Creating a society where everyone has an opportunity to live a healthy life requires action across government. While social protection measures – such as income replacement benefits, pensions, free school meals, social housing – are widely recognised as a core mechanism for reducing inequalities, the impact of structural inequalities in the economy itself has generally received less attention. This report contains case studies of economic development strategies which look beyond narrow financial outcomes as measures of success, and instead aim to enhance human welfare.

The evidence base in this field is at an early stage, but it already points towards people’s health and wellbeing being promoted by inclusive economies. This means economies that support social cohesion, equity and participation; ensure environmental sustainability; and promote access to goods and services which support health, while restricting access to those that do not. A wide variety of economic development interventions are available to local and regional bodies to create this kind of economy and the report examines these in detail.

An inclusive economies framework for improving health

This report provides a framework for practitioners to consider the interventions available and implement strategies most appropriate to their local situation. Local, regional and central government all have roles to play in shaping economies in ways that are beneficial for people’s health.

Based on the existing evidence base and the case studies developed for this report, we identify six areas that are important in facilitating local and regional approaches to developing inclusive economies:

- Building a thorough understanding of local issues – using robust analysis of both routine and innovative data sources, as in the case study on Scotland’s inclusive growth diagnostic tool.

- Leadership providing long-term visions for local economies – and designing these economies to be good for people’s health, as in the case study on Plymouth City Council’s long-term plans.

- Engaging with citizens – and using their insights to inform priorities and build momentum for action, as in the case study on the Clyde Gateway regeneration programme in Glasgow.

- Capitalising on local assets and using local powers more actively – as in the case study on economic planners’ efforts to capitalise on Leeds’ medical technology assets.

- Cultivating engagement between public health and economic development – building alliances across sectors, as in the case study on economic development and health in various levels of government in Scotland.

- Providing services that meet people’s health and economic needs together – as in the case study on Finland’s one-stop guidance centres for young people.

Cross-cutting lessons from local to national level

Four of the themes emerging from the case studies highlight the responsibilities that run across local, regional and national government and need to be embedded in thinking at every level of the system:

- Promoting economic conditions that recognise the needs of groups facing inequality – as in the case study on parental leave allowances in Sweden.

- Including health and wellbeing in the measurement of economic success – as in the case study on New Zealand’s Wellbeing Budget.

- Actively managing technological transitions and responding to economic shocks – with support for those most affected by structural shifts in the economy, as in the case study on Leeds City Council’s digital inclusion programme.

- Promoting standards of good work and wide labour market participation – as in the case study on tailored support to workers facing redundancy in Sweden.

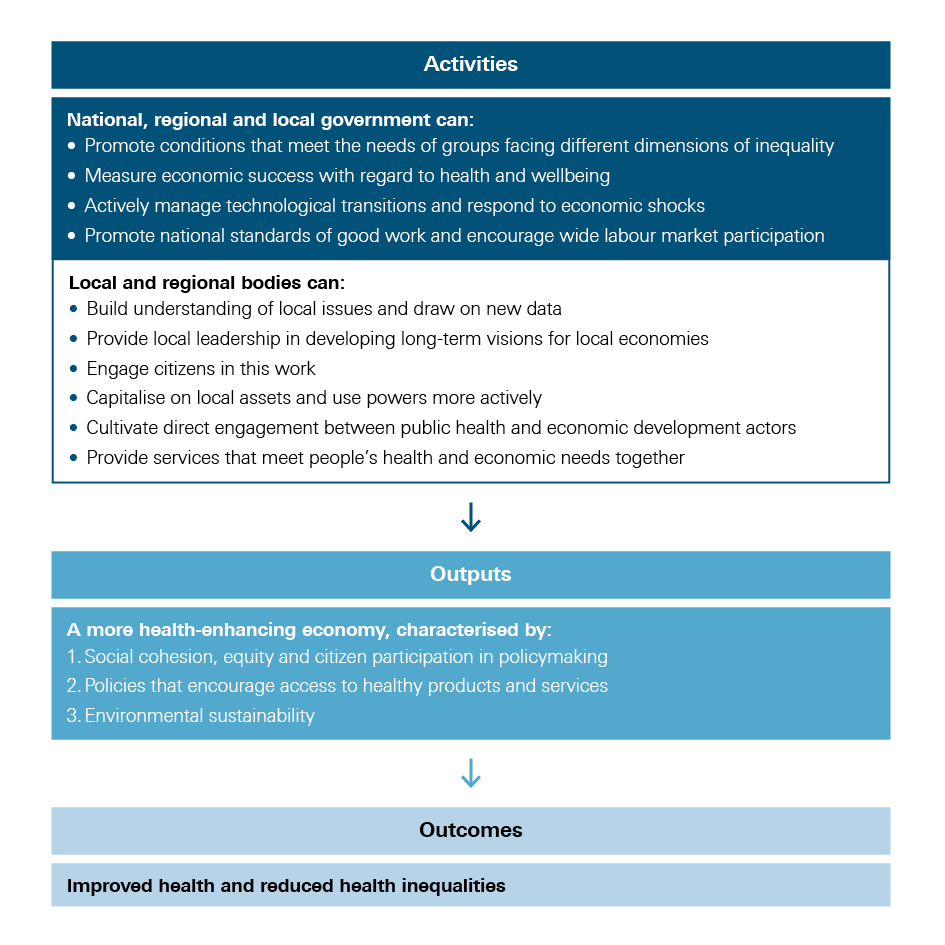

Figure 1 demonstrates how economic development activity and the implementation of the report’s key recommendations could support improved health outcomes.

Figure 1: Simplified theory of change following implementation of this report’s main lessons

What next?

While there is ample evidence to act on now, the existing evidence base does need to be strengthened. But the challenge here is that economic development policies are linked to health outcomes often through long chains of events, which are difficult to study. Understanding what the potential health impacts of economic development policies are requires clarity on the mechanisms through which these policies influence people’s health. The Health Foundation is contributing to further developing knowledge in this field by supporting a funding programme called Economies for Healthier Lives in 2020.

This report is being published as we move into the next phase of pandemic recovery, with the government focusing on how to ‘build back better’. It also comes as the UK faces considerable economic challenges linked to Brexit, decarbonisation and technological transitions. With a focus on future economic resilience, there is an opportunity for government at all levels to embed health and wellbeing in economic policies. In doing so, policymakers should aim to reduce existing inequalities and prevent their further entrenchment.

In the short term, this research report recommends the government’s priorities should be:

- Broadening the focus of economic policy beyond GDP to promote more inclusive and socially cohesive policies at a national level.

- Ensuring that the COVID-19 response measures do not lead to a widening of the attainment gap in educational outcomes, which could exacerbate existing inequalities and hold individuals and communities back in the future.

- Investing in lifelong education and skills development. Given the pandemic’s unequal impact on jobs and workers, this should mean focused investment in employment support and career guidance for young people entering the workforce, those in sectors facing the most financial instability and those who may need to change jobs due to being at higher risk of complications from COVID-19.

- Introducing local and regional measures of equitable and sustainable economic development against which to assess progress in ‘levelling up’ opportunities across the country and between socioeconomic groups.

- Targeting growth incentives towards sectors that contribute to sustainable development and growth in high-quality jobs and, in parallel, promoting better quality of jobs for workers in low-paid and insecure roles.

- Devolving more investment funding for cities and local authorities, so that local strategic investments are fully informed by local context and investing in the capability and capacity of local enterprise partnerships to create inclusive economies.

All these actions need to be driven forward and supported with strong system leadership across the various levels of government. Their implementation would be best considered as part of a whole-government approach to improving health and wellbeing. Levelling up health outcomes needs a new national cross-departmental health inequalities strategy.

Times of economic transition offer opportunities as well as risks. There are opportunities to build economies that work better for everyone, enhance people’s health and reduce inequalities. The lessons from this report will support policymakers, researchers and changemakers in contributing to the action that is needed to do this.

Introduction

This report comes at a time when both the nation’s health and its economy are in the spotlight. As the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, people’s health and the economy cannot be viewed independently. Both are necessary foundations of a flourishing and prosperous society.

The health of a population depends on more than the health care services available to it – it is shaped by the social, economic, commercial and environmental conditions in which people live. People’s economic circumstances are shaped by their income, pay and wealth, whether they have a job and the type of work they do. As the UK emerges from the immediate crisis, attention has rightly turned from protecting the NHS to rebuilding the economy. This creates an opportunity to address long-run inequalities in economic opportunity.

The UK entered the pandemic with significant inequalities in people’s health. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On – published less than a month before the national lockdown – found that people living in the UK in 2020 can expect to spend more of their lives in poor health than they could have expected to in 2010. It also highlighted that life expectancy improvements, which had been steadily climbing, have slowed for the population as a whole and declined for the poorest 10% of women. Health inequalities linked to income level (the difference between the health outcomes that the least and most socioeconomically deprived people can expect to experience) have increased. These pre-COVID-19 trends are not only true of the UK. There has been a slowdown in life expectancy improvements across most European countries while in the US, life expectancy has fallen for 3 years in a row – due in part to the dramatic growth in the number of ‘deaths of despair’ – those caused by suicide, drug overdose and alcoholism, which disproportionally affect the most deprived communities. However, the slowdown has been faster and sharper in the UK than in most other countries, except the US.

The recent Marmot Review partially attributed these trends to weakened social protection in the UK as a result of government austerity over the 2010s. As explained in Mortality and life expectancy trends in the UK, however, these trends are likely to result from several factors and the complex interactions between them. In particular, with life expectancy closely associated with living standards, it is important to view this stalling in the context of the economic shock of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent severe stagnation in living standards, with little improvement in average household incomes in the UK over the last 10 years. At the same time income inequality, though largely unchanged over this period, has remained high – a consequence of rapidly rising inequality in the 1980s.

This report focuses on how economic policy can be reshaped so that the proceeds of economic progress can be more equitably distributed. It covers policy action that seeks to influence the economic determinants of health and it comes at an important moment in terms of national policy direction for four reasons.

First, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought issues of job security and the crucial link between the economy and health to the fore. It has highlighted the number of people in the UK who are living in, or close to, poverty and food insecurity. This report can inform local and national government efforts to support recovery from the pandemic, from both a health and an economic perspective.

Second, following the 2019 general election, there was a shift in the policy context with the government’s commitment to ‘levelling up’ – reducing the economic disparities between regions of the UK. This was seen in the emphasis on skills development and improved infrastructure to link the north and south of England in the Spring 2020 Budget. There are opportunities to focus economic development in disadvantaged areas to help create more quality jobs and support people who have been economically inactive but want to get into employment. Wider government commitments include further devolution of economic development; a Shared Prosperity Fund post-Brexit; and work to develop wider measures of economic success, including metrics that track wellbeing as part of implementation of the Industrial Strategy.

Third, global factors present new challenges to the current structure of the UK economy. The nature of work is set to change radically in the near future – with growing automation of existing jobs and changes in the types of jobs available. This is likely to cause disruption to many workers but could also present opportunities if higher-quality, more productive roles are created. National and regional choices have to be made about the type of economic development that is pursued, the jobs that are created and the policies that surround the labour market.

Finally, there is the backdrop of the climate crisis. Economic activity is one of the most important determinants of carbon emissions. Carbon emissions influence people’s health through the impact of air pollution, climate breakdown and more.,, The declaration of a climate emergency by many local authorities has brought a renewed sense of urgency to this issue. The current government pledged in its general election manifesto to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 through investment in clean energy solutions and green infrastructure. UK business and industry are likely to shift further towards ‘green’ sectors and away from carbon-heavy activity, which will have widespread implications for the economy as a whole.

This report draws on case studies from the UK and around the world that provide practical insights into ways local and regional economic development can create the economic conditions to enable people to lead healthy lives. It is intended to inform the work of economic development professionals who want to improve people’s health, public health professionals who want to strengthen economies and their partners in the private or the voluntary sectors.

The Health Foundation is supporting the adoption of the lessons presented in this report through an upcoming 2020 funding programme, Economies for Healthier Lives, which will support local action and capacity-building on initiatives that seek to improve the economic determinants of health.

The role of economic development

2.1 Why consider health outcomes as part of economic development work?

A strong economy can mean high average incomes and good living standards, conditions which contribute to people’s health and wellbeing. Over the last decade, we have seen a lengthy economic shock, characterised by recession and then a slow restoration of living standards, with sustained weak productivity growth and stagnation of wages, alongside austerity policies. Nationally, inequality in wealth distribution has increased over the last decade. Poverty remains a persistent challenge; overall levels have stayed relatively constant for more than 15 years, with government data showing that in 2018/19, 22% of the UK population were living below the poverty line (after housing costs). Though unemployment was low before the COVID-19 outbreak and accompanying lockdown, this did not translate into financial stability for many people given the extent of in-work poverty in the country. 20 years ago, around 39% of people living in poverty in the UK were in a working family – before the lockdown, that figure was 56%.

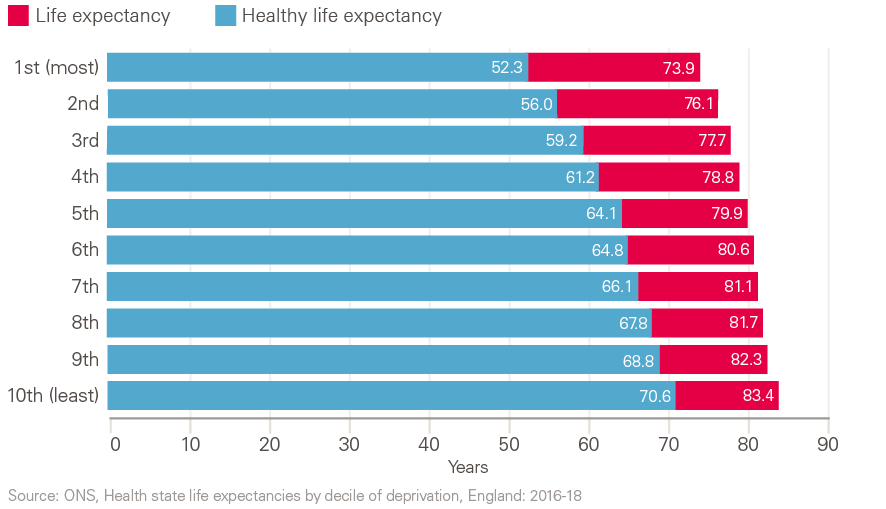

Low household income and lack of wealth can cause insecurity, stress, lack of material resources, unaffordability of healthy products and services, and more. These experiences have measurable consequences for people’s health outcomes. High income or existing wealth, by contrast, provides financial security, access to good housing and healthy food, education opportunities and other factors likely to promote good health. This is reflected in the life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth for men living in different economic circumstances (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Male life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth by decile of deprivation, England: 2016–18

Over and above income and wealth levels, recent Health Foundation analysis has shown that better job quality is associated with better self-reported health, which has not improved despite high employment levels. It has also shown that one in three UK employees report having a low-quality job in which they feel stressed and unfulfilled, that people in these roles are much more likely to have poor health, and that they are twice as likely to report their health is not good.

Good health is not simply an output of a fair and thriving economy. It is a vital input into a strong economy. Good health improves people’s wellbeing, their productivity and their ability to participate in society. People who are experiencing poor health have more limited opportunities to participate socially and economically. This represents a lost opportunity for our economy. For example, Health Foundation analysis has shown the association between health status and labour productivity. Poor health has been estimated to cost the UK economy £100bn per year in lost productivity.

National and local governments (and the partners they work with) can make conscious choices about the type of economy they promote. The choices they make will materially affect the long-term health outcomes for their populations.

There is growing interest in rethinking the fundamental purpose of the economy and challenging assumptions about how it works for everyone in society., Organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the RSA have championed the concept of ‘inclusive growth’, where the goal is to ensure that the benefits of economic progress are enjoyed by the whole of society., The RSA has also highlighted the influence of structural imbalances in the economy’s growth model on disparities in living standards across social and geographic groups in the UK. Other organisations suggest a focus on inclusive growth alone is inadequate and instead advocate ‘inclusive economies’, a concept which focuses on addressing the fundamental causes of economic and social inequality.

Creating an economy that works for everyone raises questions about how policy and economic success are measured. The output of the economy has been traditionally measured in GDP; rising GDP has been the primary measure of a strong economy and has often been assumed to be good for a population’s health, though in reality the relationship between the two is more complex. In the first half of the 1900s, increases in GDP were associated with significant growth in life expectancy. In the latter half of the 20th century and beginning of this century the association was not as strong, and in the last decade there has been sluggish growth in GDP and life expectancy improvements have stalled.

A continued focus on GDP growth statistics directs attention on policies that aim to affect the overall level of economic activity. These policies in turn shape patterns of who benefits from growth. To build economies which promote health, we believe there is a need to look beyond GDP figures to understand who benefits from growth. For example, we know that a person’s life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are closely correlated with their income and wealth. Figure 2 shows that men living in the most deprived tenth of areas in England were expected to live 18 fewer years in good health than men from the least-deprived tenth of areas. Tragically, this pattern has been repeated in the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a far harsher impact on deprived communities than wealthy ones. Our national success is not only indicated by traditional economic indicators, but should also be judged on the extent to which people in the UK experience good health and wellbeing, and whether there is a high degree of inequality in the health and wellbeing experienced by different groups. We therefore need to consider wider indicators of population wellbeing, health equity and the economic conditions that affect people’s ability to live healthy lives.

2.2 The role of economic development in improving people’s health and reducing health inequalities

Local economic development activities are typically led by local government bodies such as local authorities or local enterprise partnerships. These aim to shape economies through, for example, promoting the growth of particular types of business, supporting people into work or addressing gaps in workforce skills.

The economic determinants of health – including income level, employment status, job quality, wealth and pay – have a strong influence on people’s opportunities to live healthy lives.2 Yet many opportunities to use economic development to improve people’s health may be missed because economic development and public health strategies tend to be designed separately. Specialists in economic development may not see improving health outcomes as a priority, while public health professionals may lack the mandate, technical knowledge or relationships needed to contribute to economic development strategies. A 2017 report found that over 85% of economic development departments in local councils in England were not as engaged as they could be in tackling the determinants of health.

There are examples in the UK where health considerations are being included within economic development strategies. In England, the Local Government Association has highlighted the role that economic development can play in improving people’s health, providing insight into key issues and practical guidance for public health teams and councillors. Prosperity for All, the Welsh government’s national strategy, considers workplace health a business outcome. The Scottish government considers a sustainable and inclusive economy to be a public health priority. In 2017 the Northern Irish government consulted on a draft Industrial Strategy that considers health a broader economic outcome. There are also some local examples of closer working between public health and economic development professionals.

Despite these initiatives, more needs to be done before the contribution to improving health is treated as a core objective of economic development work.

† Where ‘poverty line’ is the threshold beyond which a household is in relative low income, which is 60% of the median household income in the UK (not adjusted for inflation). In 2018/19, this was £308 per week.

What type of economic development is best for people’s health?

The economy is pivotal in ensuring that people thrive by offering them the potential for security, dignity and fulfilment. Evidence suggests that an economy that places the health and wellbeing of its population at the centre needs to achieve the following objectives:

- Promote social cohesion, equity and participation. Economic systems which promote very high levels of economic inequality can increase health inequality, damage social cohesion and prevent society as a whole (and deprived communities in particular) from thriving. More equitable distributions of wealth and a more inclusive labour market are generally better for people’s health than wide inequality and high levels of unemployment, poverty and low-quality jobs. If citizens can participate in policymaking and priority-setting it makes the system more inclusive and can make policies and programmes more context-sensitive.

- Encourage access to products and services that are good for people’s health. Options to spend money on healthy products and services can be encouraged by the conditions in which these products are produced, sold and consumed. For example, taxes that restrict the availability of health-harming products and services (like sugary drinks) and laws that change the pattern of consumption of unhealthy foods, alcohol and tobacco (like the ban on smoking in enclosed workplaces) can encourage healthier consumption.

- Be environmentally sustainable. Many interventions that seek to reduce carbon emissions produce other health and economic benefits. For example, improving the infrastructure for active travel (such as cycle lanes) or public transport can reduce air pollution and increase physical activity, while connecting people with new employment opportunities.

3.1 Innovative approaches to economic development that promote health

Based on work developed by the RSA, Table 1 sets out how an inclusive economy differs from ‘business as usual’ and could positively influence people’s health. While more evidence is needed concerning these interventions, this framework provides a working hypothesis.

Table 1: The key features of conventional and inclusive economic development

|

Conventional economic development |

Inclusive economic development |

|

Focused on inward investment by large, conventional corporates. |

A focus on ‘growing from within’: supporting locally-rooted enterprises to grow and succeed, especially those that pay well and create good jobs. |

|

Informed by a narrow set of goals, principally maximisation of GVA and job numbers, rather than ‘quality’ of growth. |

Informed by multi-dimensional goals and success measures, from productivity to wellbeing, and a concern for the ‘quality’ of growth. |

|

Led by economic development specialists or consultants. |

Informed by cross-sector priorities and collaboration, and citizen priorities. |

|

Using narrow tools of influence to attract investment (subsidies, tax incentives). |

Using a range of policy and financial tools to actively shape markets, from procurement, planning and public asset management to workforce development and business pledges. |

|

Lack of attention on distributional effects of policies or investments. |

Ensuring that opportunities flow to groups and places that are excluded. |

|

How this influences people’s health in a local context |

How this influences people’s health in a local context |

|

May not benefit local health outcomes because:

|

May benefit local health outcomes because:

|

3.2 What economic development levers are available?

The scope to influence economic conditions differs at UK national, local and regional levels.

The full range of UK government powers can be used to support a more inclusive economy including legislation, regulation, fiscal policy, monetary policy, spatial policy, budgeting and welfare provision. They can be used to reduce the risk of economic crises, promote improvements in living standards and ensure that quality job opportunities are available. National government also has a role in setting the context for local economic development strategies. This context is set through establishment of a national strategic direction that prioritises improved health and wellbeing as a core objective and through supporting local and regional bodies to deliver on that direction, partly through devolution of powers.

Based on the case studies researched for this report and informed by the broader literature, we have identified the following opportunities for local economic development strategies to create the conditions needed for healthy lives:

- Infrastructure: The physical environment can be shaped to enable people to live healthy lives, in a way that also supports the economy to thrive. For example, economic infrastructure such as public transport systems, housing and digital infrastructure could all be designed to support better health. The planning framework provides a lever through which infrastructure can be shaped.

- Capital, grants and procurement expenditure: Subsidies, public money and supply chains can all be used to create an economy that is good for people’s health. The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 (applicable to England and Wales) offers a framework for using these levers to benefit communities.‡ For example, requirements may be set around the quality of work in public procurement, or to favour businesses that pay a living wage.

- Regulation including licensing: Devolved, local and regional governments all have some regulatory control. Local governments in England have powers around wellbeing and a general power of competence.§ The devolved nations also have some (varying) control of domestic legislation and regulation. These powers can be applied to economic development, for example through limited licensing of businesses that may be harmful to people’s health. Local and regional bodies can also use informal regulatory initiatives, like local good employment charters, to promote standards which support inclusive economies.

- Education, skills and lifelong learning: A variety of policy avenues can be used to provide opportunities for people to access training and education over their lifetime, to help them access and remain in good quality work; return to work after a period of unemployment or time spent out of the labour market; and to increase their potential.

- Labour market programmes: Interventions that promote labour market inclusion by helping people enter or remain in good quality jobs can enhance people’s health. For example, return-to-work interventions could be tailored for people with health conditions that act as barriers to employment. These can run alongside initiatives to boost job quality, ensuring employers give consideration to job security, job design, management practices and the working environment. Anchor institutions, as large employers with an interest in their communities, are ideally placed to run these kinds of programmes. This is particularly true in deprived areas with limited economic opportunities, where anchor organisations are often in the public sector.

- Financial systems and approaches to investment: Access to and control over investment allows bodies to use their financial influence flexibly and across sectors and businesses that promote people’s health and equity. For example, public bodies could commit not to invest in health-harming sectors.

3.3 The current evidence base

Developing an evidence base in this field is challenging. Economic development policies are often long-term initiatives that are linked to health outcomes through long chains of events. Understanding their potential impact requires clarity on the assumed mechanisms through which economic development approaches are expected to influence health outcomes. Given that these mechanisms operate through multiple factors across a complex system, traditional approaches to evidence building will not always be possible or appropriate.

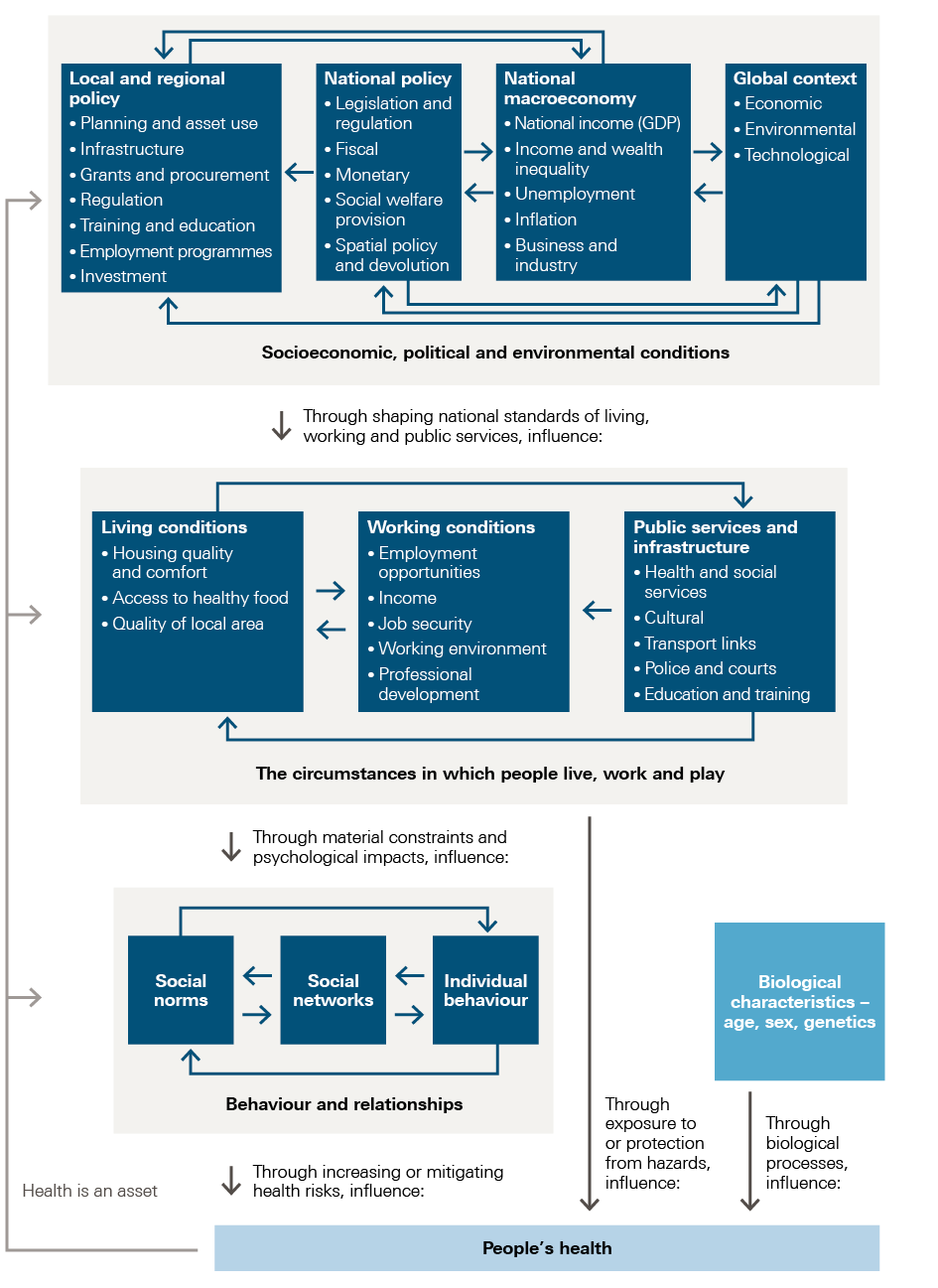

Economic development policies tend to act on intermediate outcomes such as income and employment status, which themselves influence health. Figure 3 brings together the findings of key commissions and reviews, to inform a systems overview of how the economy influences health outcomes.

Figure 3: A systems overview of how the economy affects people’s health

Source: Drawn from the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2010, Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1993, and Naik et al, 2019.

Recognising the complexity involved, recent systematic reviews have brought together the evidence base around the economic factors and interventions that affect people’s health. Naik et al, 2019, reviewed the evidence on the influence of high-level economic factors such as markets, finance, the provision of welfare, labour markets and economic inequalities on people’s health and health inequalities. The authors found evidence that the risk of dying from any cause is significantly higher for people living in socioeconomically deprived areas than for those living in areas with high socioeconomic status. They also found good evidence that wide income inequality is associated with poor health outcomes. The review showed that action to promote employment and improve working conditions could help to improve health and reduce gender-based health inequalities. Likewise, the review suggests that market regulation of food, alcohol and tobacco is likely to be effective at improving health and reducing health inequalities.

In contrast, there was clear evidence that reductions in public spending and high levels of unaffordable housing were associated with poorer health outcomes and increased health inequalities. The review also found clear evidence that economic crises (acute shocks that involve changes to employment and GDP, such as the 2008 financial crisis) have been associated with poorer health outcomes and increased health inequalities. This final point is highly relevant as we move into recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic impact.

Despite increasing evidence about key economic factors that influence people’s health and health inequalities, the knowledge base regarding which interventions are beneficial for health and how specific interventions affect health outcomes could be improved. This report draws on the best available evidence and examples of good practice in the UK and elsewhere; in parallel, the Health Foundation is investing in strengthening the evidence base by funding the SIPHER programme (through the UK Prevention Research Partnership), which aims to model the systems implications of inclusive growth policies, including on health outcomes. Similar work linked to local practice is needed. The Health Foundation will also be supporting local action and capacity-building in this field through the Economies for Healthier Lives funding programme in 2020.

‡ The Public Services (Social Value) Act came into force for commissioners of public services in England and Wales on 31 January 2013. The Act requires commissioners to consider the how procurement could secure not only financial value, but also wider social, economic, and environmental benefits. See www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-value-act-information-and-resources/social-value-act-information-and-resources

§ The general power of competence was brought into force for local authorities in England on 18 February 2012. It enables them to do ‘anything that individuals generally may do’ for the wellbeing of people within their authority, meaning they have general powers over and above their statutory responsibilities.

Learning from UK and international case studies

The Health Foundation worked with the RSA and Demos Helsinki to produce several UK and international case studies exploring the evidence and practice on economic approaches to improve health and reduce health inequalities. These have highlighted a series of common local and national enablers– as well as showing where further work is required.

The Appendix provides brief background information on the case studies used in this report. Each case study provided a rich picture of approaches taken to link economic development to improvements in health. While this report highlights specific lessons, more detailed descriptions of the case studies will be published separately by the RSA.

Six themes were identified as important in facilitating local and regional approaches to developing inclusive economies:

- build a thorough understanding of local issues with robust analysis of both routine and innovative data sources

- provide local leadership in developing long-term visions for local economies that are good for people’s health

- engage with citizens to inform priorities and build momentum for action

- capitalise on local assets and using statutory and discretionary powers more actively

- cultivate direct engagement between public health and economic development actors

- provide services that meet people’s health and economic needs together.

4.1 Build a thorough understanding of local issues with robust analysis of routine and innovative data sources

Economic strategies need to be grounded in good quality data, rigorous analysis and an understanding of how economic conditions are affecting local people if they are to influence people’s health outcomes.

At present the breadth of data available is limited and patchy. While economic indicators (such as unemployment and employment levels) are routinely produced by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), they can lack the granularity needed to understand who is and who is not benefiting from economic activity. Local governments will generally have data on the number of jobseekers in their area but may not be using data sources such as Employment and Support Allowance records to understand the number of people who struggle to find work due to poor health. Other indicators, which are not routinely tracked, may also provide valuable insights. These include measures such as the quality of local jobs, the percentage of procurement expenditure spent locally or the number of people receiving the living wage.

Where data does exist, more robust analysis could contribute to building evidence on the relationship between local and regional economic development interventions and health outcomes.

Case study example: Scotland

Scotland has a national inclusive growth agenda, which aims to achieve economic growth through promoting good quality jobs, equality, opportunities for all and regional cohesion. To aid this agenda, localities are using an inclusive growth diagnostic tool to understand the interaction between the economic and social challenges in their area.

The inclusive growth diagnostic tool is an interactive data platform that brings together indicators of health outcomes (such as life expectancy at birth) and economic performance (such as the number of businesses and total exports). Indicators fit within five categories: productivity, labour market participation, population demographics, people’s health and skills, and natural and physical resources. They are available for every one of Scotland’s 32 local authorities. Some indicators can be broken down by protected characteristic, such as gender, allowing places to develop a detailed understanding of local needs.

The tool enables local authorities to assess their performance through benchmarking on a range of indicators against neighbouring local authorities, the national average and the best-performing area for each indicator. Authorities can then identify areas in which their place is underperforming.

The tool prompts users to identify environmental and social conditions that may be contributing to this underperformance from a comprehensive list. It also allows places to prioritise areas for targeted interventions, through ranking the identified constraints based on their impact and deliverability of interventions to alleviate them. It therefore supports places to prioritise between economic development interventions, as relevant to local need.

Scotland’s Centre for Regional Inclusive Growth – a partnership between government and academia – has produced the inclusive growth diagnostic tool. It supports local authorities in making evidence-based policy to build and deliver inclusive growth in Scotland and, in turn, generates insights to build the evidence base. As the tool is relatively new, there is a lack of evidence about resulting changes in practice.

4.2 Provide local leadership in developing long-term visions for local economies

At the local level, there are significant opportunities for leaders across sectors to collaborate on shared long-term visions for economies that have health and wellbeing at the centre. The 2017 UK Industrial Strategy required local enterprise partnerships and mayoral combined authorities in England to develop local industrial strategies. This requirement provides a platform for places to develop their locally relevant long-term economic visions, with input from leaders from across sectors. More recently, places are considering how to rebuild their economies after the damage of the COVID-19 crisis. Local and regional governments should include leaders from across multiple sectors in the development of strategies for restarting local economies.

Taking an inclusive approach to developing these strategies can be a slow process. However, if a wide range of leaders are included in the development of plans, they are more likely to adopt the shared vision and to implement the economic development policies and practices that contribute to it. Once in place, the shared understanding these strategies create can be helpful when local leaders inevitably face difficult trade-offs between the economy and health. For example, they may need to decide whether to provide a licence to operate to a business that could negatively affect people’s health but could bring employment opportunities to their area (such as alcohol retailers or gambling shops). A shared understanding of the kind of economy that places are aiming to create provides a unifying framework for these decisions.

Case study examples: Plymouth and Burlington

The Plymouth Plan 2014–2034 is a vision for the future that prioritises health and growth as two core objectives of local policy. The local authority has taken the role of system leader and facilitator of cross-sector collaboration on the economy and health within the remit of this plan. Central to this is the Inclusive Growth Group responsible for creating an ‘economy to truly serve the wellbeing of all the people of Plymouth’. This group brings together representatives from across the NHS, manufacturing, education, the city council, retail and technology. They have developed a set of interventions to support inclusive growth in the city, one of which is a charter mark for local businesses and organisations that make a commitment to supporting inclusive growth, including health and wellbeing outcomes. Another is a leadership programme that will upskill local changemakers from across the local public, private and third sectors to tackle social and economic inequalities.

In Plymouth, the council has made a commitment to double the size of the local cooperative economy (the number of businesses owned and run cooperatively). There is some evidence to suggest that cooperatives may promote the health of employees, for example through greater control over their employment and better job retention in times of economic recession, though further research is needed.

The US city of Burlington is another example of where the economy and health have benefited from a long-term vision and strong leadership. In 1984, the city’s Community and Economic Development Office published Jobs and People, its 25-year strategic blueprint for the city’s economic development. The strategy was supported by six core principles that continue to guide economic development in the city today:

- encouraging economic self-sufficiency through local ownership and the maximum use of local resources

- equalising the benefits and burdens of growth

- using limited public resources to best effect

- protecting and preserving fragile environmental resources

- ensuring full participation by populations normally excluded from the political and economic mainstream

- nurturing a robust ‘third sector’ of private, non-profit organisations capable of working in concert with government to deliver essential goods and services.

The research for this case study found that resulting economic development initiatives were seen to have fostered social capital and created a sustainable, locally rooted economy that is less prone to shocks. Its business models provide good jobs, skills development and liveable wages, healthy and sustainable food systems, quality housing and improved public infrastructure. The city has been recognised for its success in promoting health – in 2008 it was named the healthiest city in the US by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It has also been recognised by the United Nations as a regional centre of expertise in sustainable development.

There are more tangible health outcomes in Burlington than in Plymouth because the Burlington approach has been implemented consistently over many years. It is too early to see health effects from the more recent work in Plymouth and further research will be needed to understand the impacts that this work will have.

4.3 Engage with citizens to inform priorities and build momentum for action

While it is becoming more common for local governments to seek community feedback through consultations, it is not routine for local governments to include citizens in generating economic policy. As a result, economic decision-making may not always consider citizens’ needs or match their expectations – such as skills programmes that do not align with people’s aspirations to work in certain sectors, or employment interventions that fail to address locally relevant barriers to work.

The direct consequences of inequality and uneven wealth distribution underline the importance of involving local citizens in economic policymaking. Citizens are less likely to view their lives in silos than public services are, so public engagement may encourage policies and programmes that are better integrated and more relevant to local contexts. Citizen engagement may also ensure that decisions around economic policy reflect the needs of the most deprived populations.

Case study examples: Glasgow and Auckland

The Clyde Gateway regeneration programme in the east end of Glasgow, which is a relatively deprived part of the city, is one example of when citizens have been extensively engaged in identifying their own needs. The work of the regeneration programme is steered by a community residents’ committee and has been shaped by multiple community engagement events over the years. By 31 March 2019, these events included 7,848 community participants. Through this engagement, activities of the programme are directed by community priorities that, for the first 10 years, included job creation, investment in community assets and a restoration of pride in local neighbourhoods. The programme has also worked with local communities, schools and businesses to develop career pathways and support for residents to access and hold new jobs being created in the area. Local people have taken up over 900 new jobs since the programme began in 2008.

The Southern Initiative (TSI) in South Auckland, New Zealand, is a place-based model of social and economic development and a quasi-independent body of Auckland Council. Compared to the area of Auckland as a whole, the southern part of the city has relatively large Polynesian and Māori populations, a lower average age, lower average income and lower levels of formal education. The population also has a higher proportion of people living with one or more disability in comparison to the city as a whole.

TSI explicitly recognises the importance of economic circumstances to people’s health outcomes and seeks to make systematic and grassroots changes to ensure South Auckland community members can lead healthy lives. The team works with a range of formal, informal and grassroots organisations to design, prototype and apply innovative, community-led responses to complex social and economic challenges. TSI promotes community ownership of interventions that seek to reduce deprivation and disadvantage. Therefore, the team actively seeks out and supports a wide range of community initiatives that broaden prosperity, foster wellbeing, promote innovation and technology, and develop healthy infrastructure and environments.

TSI offers financial, administrative, network-building and skills-training support, but the team also helps with organisational development. The initiative has used social procurement and social wage strategies to support and engage businesses that are locally rooted and create good quality jobs. TSI has also established an intermediary organisation to link Pacific Islander and Māori-owned businesses to clients and buyers. Over 2019, NZ$4m worth of contracts were awarded to businesses registered with this organisation.

4.4 Capitalise on local assets and use local powers more actively to shape inclusive local economic conditions

While formal powers can be used to shape their economic conditions, every place has opportunities to capitalise on its own local assets – such as local industrial sectors, the natural environment, cultural heritage and anchor institutions.

To improve the economic circumstances that shape people’s health through cross-sector interventions, places need to increase their innovative use of the powers and assets available to them. In the UK, national procurement systems are focused primarily on reducing costs, with relatively limited local or regional ability to choose suppliers for other reasons, such as the value they add to the local community by supporting local jobs. However, in England and Wales the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 gives a legislative responsibility for public authorities to engage in procurement and related activities with consideration of economic, social and environmental wellbeing. This approach could be widened to form the basis of locally relevant social value frameworks that extend beyond pure economic measures of social progress and are used in all key decisions.

Given the diversity of the assets and powers that places may choose to draw on, robust evaluation of the impact of these approaches is challenging. This is an area for further research.

Case study example: Leeds

Leeds has a strong history in medical technology innovation and has many health care institutions, including teaching hospitals, research centres and national NHS bodies. This gives the city an advantage in developing innovative approaches to the challenges of health and inclusive growth, and related employment opportunities. Leeds City Region Enterprise Partnership (LEP) is currently seeding 250 health tech small and medium enterprises from within this ecosystem. It has announced that its local industrial strategy will focus on harnessing the potential of Leeds’ health care assets.

This work is supported by local networks, including the Leeds Academic Health Partnership – a collaboration between three universities in Leeds, NHS organisations and third sector partners. The project pools funding to cover an eight-strong team that is tasked with embedding learnings from academic research into practical action that supports economic growth, specifically in the health and social care sector. There is also an Academic Health Sciences Network, which in collaboration with the LEP leads on drawing international investment and engagement into the city, through commercialising the intellectual property derived through NHS research and innovation. The University of Leeds heads the Grow MedTech partnership, a consortium of six academic institutions in Yorkshire that offer specialist support for innovation in medical technologies. The consortium was established in 2018 with £9.5m in funding from Research England.

While this combination of industries is unique to Leeds, the premise of engaging with existing work and infrastructure within the city is applicable across the UK.

4.5 Cultivate direct engagement between public health and economic development

There are many barriers to collaboration between economic development and public health teams, including the fact that they are often seen to ‘speak different languages’, they may have different goals and there may not be strong relationships between these teams. A further factor to consider is that local government in the UK is under significant pressure, with much smaller budgets than in the past and therefore restricted ability to intervene in the economy and health. However, there is also increasing recognition that significant potential may be realised by building collaborations between public health and economic development and broader coalitions of organisations and actors.

Case study examples: Leeds and Scotland

Leeds City Council has aligned the health and inclusive growth agendas through two core strategies that are formally connected by an overarching narrative. The health and wellbeing strategy has the ambition of ‘a strong economy with quality local jobs’ and the inclusive growth strategy has the ambition of Leeds being ‘the best city for health and well-being’. In Leeds, case study research found that collaboration between public health and economic development was good at senior levels, but that interaction is limited by capacity. Joint appointments across health and local government were seen as good practice, with public health leadership providing technical expertise and advocacy.

In Scotland, formal links between economic and health policy and practice have been created through joint committees and cross-sector priorities. NHS Scotland is actively involved in informing regional growth deals. Scotland’s Council of Economic Advisers advises Scottish ministers on improving the competitiveness of the Scottish economy and reducing inequality. It has nine members, including Sir Harry Burns, Scotland’s former Chief Medical Officer. Scotland’s Chief Social Policy Adviser has a public health background and collaborates closely with key economic policy officials. Local and regional coordinating structures (such as regional health boards, community planning partnerships and city region partnerships) are increasingly enabling health and economic development to be considered together. This includes the creation of joint posts explicitly to consider economic development and health together – for example, in Glasgow City Council. Case study research found that this was particularly effective in relation to key agendas, such as fair work, employability and child poverty.

4.6 Provide services that meet people’s health and economic needs together

Disjointed services can present a barrier to positive outcomes in people’s lives. Someone in difficult circumstances may need to access a range of services to fulfil their needs, for instance income support, health care, job centres and digital access points like libraries. Often these services are separate (physically and institutionally), which may cause barriers to access. Holistic approaches to wellbeing are being increasingly adopted in health care, such as social prescribing and integrated care systems. It is important that this move towards service integration includes economic services, such as those supporting access to employment.

Case study examples: Plymouth and Finland

In Plymouth, community economic development trusts – organisations owned and led by the community – aim to bring long-term social, economic and environmental benefits by supporting the growth of local businesses, helping local people into good jobs and fostering community initiatives. Plymouth has opened four wellbeing hubs co-located with these trusts. Designed as part of a ‘one system, one aim’ approach, the hubs are intended as places where people can go for support and to connect with a range of services and activities. They aim to improve the health and wellbeing of local people and reduce health inequalities, to improve people’s experiences of care and support in the health and care system.

Every wellbeing hub offers at least: advice on wellbeing, employment, debt, and accessing health services; support in health care decisions; mental health support and referrals; and opportunities to volunteer. Other services provided by individual centres include CV and interview support, a friendship café and parenting support. Co-locating these centres within community economic development trusts means that people with health and economic needs can access support in one place. The first hub was established in 2018 and the network is still under development, so an evaluation of the impacts is not yet available.

In Finland, there are now 70 one-stop guidance centres where people younger than 30 years of age can access help on issues related to work, health, education and everyday life. They aim to support young people to transition into successful adulthood through finding pathways into education and employment. The centres are staffed by employees of organisations from a range of sectors, including recruiters from the private sector, skills trainers from the third sector, youth and employment counsellors, social workers, nurses, psychologists and outreach workers. Their services are designed to be as accessible as possible – young people can visit without an appointment or access services online and over the phone.

Services provided at the centres include career and education counselling, training (in social skills and skills required for everyday life, like housework and cooking) and support with tax, housing and welfare. The social workers and health care staff can also provide counselling for health and social security issues. If a visitor has long-term needs, they will be matched with a professional who is given responsibility for ensuring they access a programme of support.

Key performance indicators are still being developed to evaluate the impact of these centres. Their very nature makes them difficult to evaluate – they are designed to be informal, with minimal data gathering, and act as referral centres, which makes it challenging to track visitor outcomes. However, case study research for this report found that the approach has formed a new culture that bridges silos and prioritises visitors’ needs. Research on visitors’ experiences has also found that the initiative gives people a feeling of agency and provides useful support.

These are examples of integrating health and social support with services that help people into better economic circumstances. In doing so, the initiatives ensure that services address the health issues affecting people’s ability to work, and the employment issues affecting their health. While these case studies showcase two possible models for such services, research may be needed to explore different working arrangements and inform best practice.

Cross-cutting lessons from local to national level

Some themes emerging from the case studies highlight wider societal responsibilities that run across local, regional and national level and need to be embedded in thinking at every level of the system. These include:

- promoting economic conditions that recognise the needs of groups facing inequality

- including health and wellbeing in the measurement of economic success

- actively managing technological transitions and responding to economic shocks

- promoting standards of good work and encouraging wide labour market participation.

5.1 Promote economic conditions that recognise the needs of groups facing inequality

Inclusivity is a policy agenda that cuts across different dimensions of inequality, including gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic group. Despite increasing awareness of the importance of diversity and inclusion throughout society, there are still groups who are systematically and enduringly economically disadvantaged. For example, from October to December 2019, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for people of white ethnicity in the UK was 3.4% – but for people of black ethnicity, or Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds, this figure was 8%. Unemployment rates also vary by gender in the UK. National unemployment rates tend to be higher for men than for women – but more women than men are classed as ‘economically inactive’ (not in employment and not unemployed), mainly because they are looking after family. A truly inclusive economy should ensure equality of opportunities across all of these different groups and account for how multiple dimensions of inequality (such as those linked to ethnicity and gender) may interact.

The case studies from Sweden and Burlington, US, highlight examples where efforts have been taken to support labour market participation in a pre-pandemic context. The COVID-19 pandemic and the wider governmental and societal response has further exposed the existing health inequalities in our society. There is emerging evidence that some groups within the population are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and a Public Health England review found the greatest risk factor for dying with COVID-19 is age. The risk was also higher among those living in more socioeconomically deprived areas, among black and minority ethnic groups, and in certain occupational groups. As we begin to recover from the pandemic and face considerable economic uncertainty, there needs to be long-term thinking to avoid exacerbating existing inequalities. Preventing such an outcome will require a national cross-departmental health inequalities strategy.

Case study examples: Sweden and Burlington

Sweden’s labour market is characterised by its comparatively equal gender participation. In January 2012, the country implemented the dubbeldagar (‘double days’) reform. This enables both parents to take paid full-time, wage-replaced leave simultaneously. Parents can use it for up to 30 days in the child’s first year of life, either all at once or staggered throughout the year. Research into the effects of this reform has found consistent evidence that fathers’ access to workplace flexibility improves maternal postpartum health. One study compared the health of mothers who had their first-born child in the 3 months leading up to the reform with those who had their first-born child in the first 3 months after the reform. When looking at the first 6 months postpartum for both groups, it found that mothers who gave birth after the reform were 26% less likely to receive an anti-anxiety prescription. They were also 14% less likely to make an inpatient or outpatient visit to hospital for childbirth-related complications and 11% less likely to receive an antibiotic prescription.76

Separate research has indicated that leave policies influence people’s employment opportunities and decisions and that ‘family-friendly’ leave policies (which seek to help workers to balance employment with family life) may be at least partially responsible for high levels of employment for women in Sweden.

The Champlain Housing Trust (CHT) in Burlington, Vermont, US is an example of this approach in action locally. CHT is a pioneering community land trust that manages land and housing for long-term community benefit. CHT’s strategy for 2020–2022 includes an inclusive human resources objective, which is to attract ‘a staff of talented, dedicated, and highly motivated individuals from a wide variety of backgrounds, races, and ethnicities representative of the communities it serves, who are committed to carrying out CHT’s mission, vision, and values’. CHT has sought to achieve this objective by placing its job advertisements at its rental housing sites, on the internet and on local job boards to attract members of more disadvantaged communities. In 2019, CHT reported that 85% or fewer of its staff identified as white (Vermont’s population is 94.33% white).

5.2 Include health and wellbeing in the measurement of economic success

‘What gets measured, matters’ is a truism that applies to definitions of economic and social progress. Several indicator sets are available for measuring economic performance (for example, work by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation with the University of Manchester and the Centre for Progressive Policy). However, there is a lack of consensus around which metrics should be used to understand the relationship between economic development and people’s health or health inequalities. This problem is compounded further by a lack of clarity around what the mechanisms are through which these effects may occur, and by the long timescales that are involved in the relationship.

Case study examples: Scotland and New Zealand

Scotland’s National Performance Framework provides a shared template for promoting wellbeing in the country, supported by an overarching purpose and a set of strategic objectives, national outcomes and national indicators and targets. The framework has evolved to enable local and national policymakers to:

- structure services and manage their performance in a way that prioritises outcomes over outputs

- align policy and promote collaboration across departmental and agency silos

- develop policymaking processes and tools (such as logic models) that more explicitly link strategies, actions and programmes to desired outcomes.

These tools are seen to have helped to align policy and practice across organisational boundaries and to introduce health considerations into economic decision-making. Yet the case study research suggested that, despite its inclusive growth ambitions, the Scottish government may still be prioritising conventional economic development activities.

In New Zealand, the scope of economic policy has widened over the past few years to promote wellbeing rather than just GDP. The Treasury’s Living Standards Framework was developed in the early 2010s as a wellbeing-oriented, multidimensional, empirical policy analysis toolkit that measures and analyses a range of indicators across four assets, described as ‘capitals’: natural capital, human capital, social capital, and financial and physical capital.

As outlined in the Health Foundation’s Creating healthy lives report, in 2019, the New Zealand government’s Wellbeing Budget put the Living Standards Framework at the heart of its policy agenda. Under the new budget process, priorities are explicitly structured around intergenerational wellbeing. This case study provides an example of how using broader measures of success can create the right incentives for a shift towards long-term investment approaches within government. However, there are technical challenges in putting this into practice. Quantifying the costs and benefits of policies is far more difficult when prioritising between the four capitals. This makes it difficult to weigh trade-offs between, for example, productivity and inclusiveness. The thorny issue of ‘discount rates’ – where future benefits are given a lower value than immediate benefits – also highlights the difficulty of balancing long-term investment in preventative approaches with the need for short-term impact.

5.3 Actively manage technological transitions and respond to economic shocks

The coming years will present technological transitions that will reshape local economies with significant opportunities and risks for population health. For example, automation may lead to negative, as well as positive, changes in the nature of work and quantity of work available. It is vital that government, businesses and other stakeholders make coordinated efforts to capitalise on opportunities and mitigate any negative effects of these changes for people’s health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also tested local and regional ability to deal with economic shocks. While it will take time to fully understand the implications of this current shock, the general principle of responding to support those most affected by structural shifts in the economy is key.

Case study examples: Leeds and Saarland

One example of this type of action is the Smart Leeds programme from Leeds City Council, which aims to identify and deliver new technologies and innovative solutions. It also aims to secure full digital inclusion in the city and has rolled out the UK’s largest tablet lending scheme, which is open to those without access to the internet or who lack basic digital skills. This move pre-empts the increasing digitisation of services, such as the online Universal Credit portal, and the negative effects this could have by further isolating digitally excluded people.

Another example, which demonstrates how devolution of power away from national government can support locally relevant management of an economic transition, is that of Saarland. The area is an old mining and steel region in south-west Germany, which faced an economic crisis in the 1970s and 1980s as its traditional industries collapsed. However, compared to post-industrial regions of the UK and US, the region was able to avoid much of the social trauma associated with deindustrialisation. A key factor in creating economic resilience to this transition was strong regional governance arrangements. The German federal structure had more devolved powers than the UK and US in the 1970s and 1980s. At the same time, Saarland – as with all regions of Germany – had considerable powers and finances, enabling it to determine where to put money and what to prioritise.

These factors enabled Saarland to take a proactive approach to managing and mitigating the effects of structural economic change. Rather than drastic or immediate action to close mines or steelworks, these workplaces were kept afloat by the regional government for as long as possible, meaning the jobs they provided were preserved. This allowed a gradual transfer of workers, people, technology and skills to alternative sectors, mainly the automotive industry and engineering. It therefore avoided mass unemployment and the potential impact that this may have had on people’s health.

5.4 Promote standards of good work and encourage wide labour market participation

The availability of good work in the population is likely to affect health and wellbeing. Good work, as defined by the RSA in 2020, is that which provides people with enough economic security to participate equally in society; does not harm their wellbeing; allows them to grow and develop their capabilities; provides the freedom to pursue a larger life; and nurtures their subjective working identity. Access to good work provides access to basic living standards and the opportunity for community participation. Inadequate pay, unemployment and insecure, low-quality work are well known to negatively affect people’s health through the influence of deprivation, social isolation, work-related injury risks and exposure to poor working conditions.17, Government can influence the quality of work through standards, guidelines, conditional business support and regulation. It also has influence over the distribution of work through targeted interventions to increase employment – including developing national employment and education strategies for particularly disadvantaged groups, such as prisoners.

Case study examples: Scotland and Sweden

Scotland has adopted a variety of ways of actively influencing the quality of work. These include voluntary approaches, such as ‘fair work’ business pledges and business support to boost productivity and worker wellbeing. Another approach includes a condition attached to loans from Scottish Enterprise that businesses taking out loans must provide quality work, defined as paying ‘the Living Wage, with no inappropriate use of zero hours contracts or exploitative working patterns’. In 2018/19, Scottish Enterprise reported creating 9,489 new jobs paying at least the real living wage.

In Sweden, labour market participation has been helped by job security councils – non-profit (and non-state) organisations set up by collective agreements between employers and social partners in various sectors. These have existed since the 1970s. Whenever a company covered by a collective agreement announces layoffs, the councils provide employees with tailored re-employment coaching, counselling to cope with sudden job loss, competency development training and activity plans. They are funded by social partner contributions and companies in collective agreements, with a contribution of around 0.3% of the company’s payroll.

The results of the job security councils are encouraging:

- over 85% of displaced workers find new jobs within a year

- 60% find a new job with equal or better pay

- around 50% take on jobs with similar skill requirements, 24% with higher and 17% with lower requirements

- a mere 2% end up relocating.

These results are significantly better than for most other OECD countries. The success of the councils stems from their ability to offer services and guidance rapidly, and in a personalised manner to the sector and to the employee. Legislation is also key to their success; Sweden has a mandatory advance notification period of 6 months for redundancy, during which employers allow the job security councils to support workers. Early intervention aims to minimise the time during which a worker will be unemployed. Given that a quick return to work may minimise the adverse health effects of sudden unemployment, this intervention may benefit people’s health.

This example demonstrates the capacity of non-state actors to provide rapid assistance to workers affected by structural change, particularly when supported by legislation.

Ongoing challenges

The topics explored in this report are complex. It is not surprising, therefore, that significant uncertainties remain in how economic development can best be used to improve people’s health. This chapter highlights three of the most pressing challenges:

- how to use economic development in a way that is good for people’s health and environmentally sustainable

- the need to strengthen the evidence base

- resolving the tension between market efficiency and economic localisation.

6.1 Using health-promoting, environmentally sustainable economic development

Latest evidence suggests that avoiding catastrophic climate change requires a rapid transition to decarbonise the economy. Therefore, a major challenge for the coming years is how to develop an economy which both creates conditions that are good for people’s health and is environmentally sustainable. This issue is recognised in the UK Industrial Strategy, which identifies clean growth as a key challenge and focuses on developing a UK zero-carbon industrial sector.