Foreword

It has been a great privilege to chair the COVID-19 impact inquiry. When the inquiry began last autumn, it was still reasonable to expect that by the summer of 2021 we would be in a ‘post-pandemic’ phase. As the months have elapsed it has become clear that we will be living with the pandemic itself, as well as its consequences, for a long time to come. And while still not yet over, there are already some clear messages about the uneven impact it has had on different groups within society.

With many words already written about the pandemic, and so much more to come, we did not set out to tell the whole story of COVID-19’s impact and the measures to contain it. Instead, we have sought to draw together thinking across a variety of disciplines, to situate COVID-19 in the wider picture of health inequalities and to understand how this extreme experience may influence the journey towards greater equality.

In doing so we were hugely assisted by an Expert Advisory Panel, with expertise spanning research, civil society and public service. The panel’s broad understanding of the dimensions and determinants of health, across the nations and regions of the UK, was invaluable in challenging and enriching our discussions.

We were able to draw on research being written in real time as the pandemic moved from the first wave into its extended second wave. Some early impacts were partially reversed as restrictions ebbed and flowed. Others have become entrenched, often with uneven effects, with remote services proving more accessible for some while risking exacerbating problems of digital exclusion for others.

Our guiding principle was understanding how the UK’s experience of the pandemic could inform the decisions of a government committed to improving the health of its population, shining a light on the key issue of recovery.

The inquiry found that the shape of the UK’s recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, the last major global shock, had a direct bearing on our experience of the pandemic. In turn, we can expect the nature of the recovery from the pandemic to shape our experience of the next global shock, whatever it may turn out to be. That makes it imperative to aim for a recovery that builds economic and social resilience, with ‘levelling up’ not limited to geographical areas of disadvantage but also addressing the needs of groups who have experienced the most damaging impacts of the pandemic.

The legacy of the pandemic is all around us in unmet health need, mental health problems, gaps in educational attainment, loss of employment and financial insecurity. If we are to avoid these becoming long-term scars, it’s time to confront our choices about how we value people. A recovery led by investment in people and communities – in health, housing, skills and education – along with a safety net to protect the most vulnerable, will pay dividends for the nation’s health and prosperity in the longer term.

Dame Clare Moriarty

Chair, COVID-19 impact inquiry Expert Advisory Panel

Executive summary

As the success of the COVID-19 vaccination programme sets the UK on a course towards recovery, it is essential to learn the lessons of the past 18 months. What started as a health crisis rapidly developed into an economic emergency, with government taking unprecedented action to protect people’s lives and livelihoods. The pandemic has shown that health and wealth are inextricably connected. A sustainable recovery needs to create a stronger, more resilient economy and will require purposeful commitment to ‘level up’ health and reduce the stark inequalities exposed by the pandemic.

Although COVID-19 has challenged governments around the world, the UK was notable in entering the pandemic with life expectancy stalling for the first time in a century and falling for some. Following the 2008 financial crisis, public services had been eroded and the underlying economy and social fabric frayed.

Over the first year the UK experienced some of the worst outcomes internationally, with 119,000 excess deaths by 13 March 2021. Measures to suppress the virus have led to the UK experiencing a huge economic shock – including a 9.9% drop in GDP in 2020 compared with a 4.8% drop across all OECD countries.

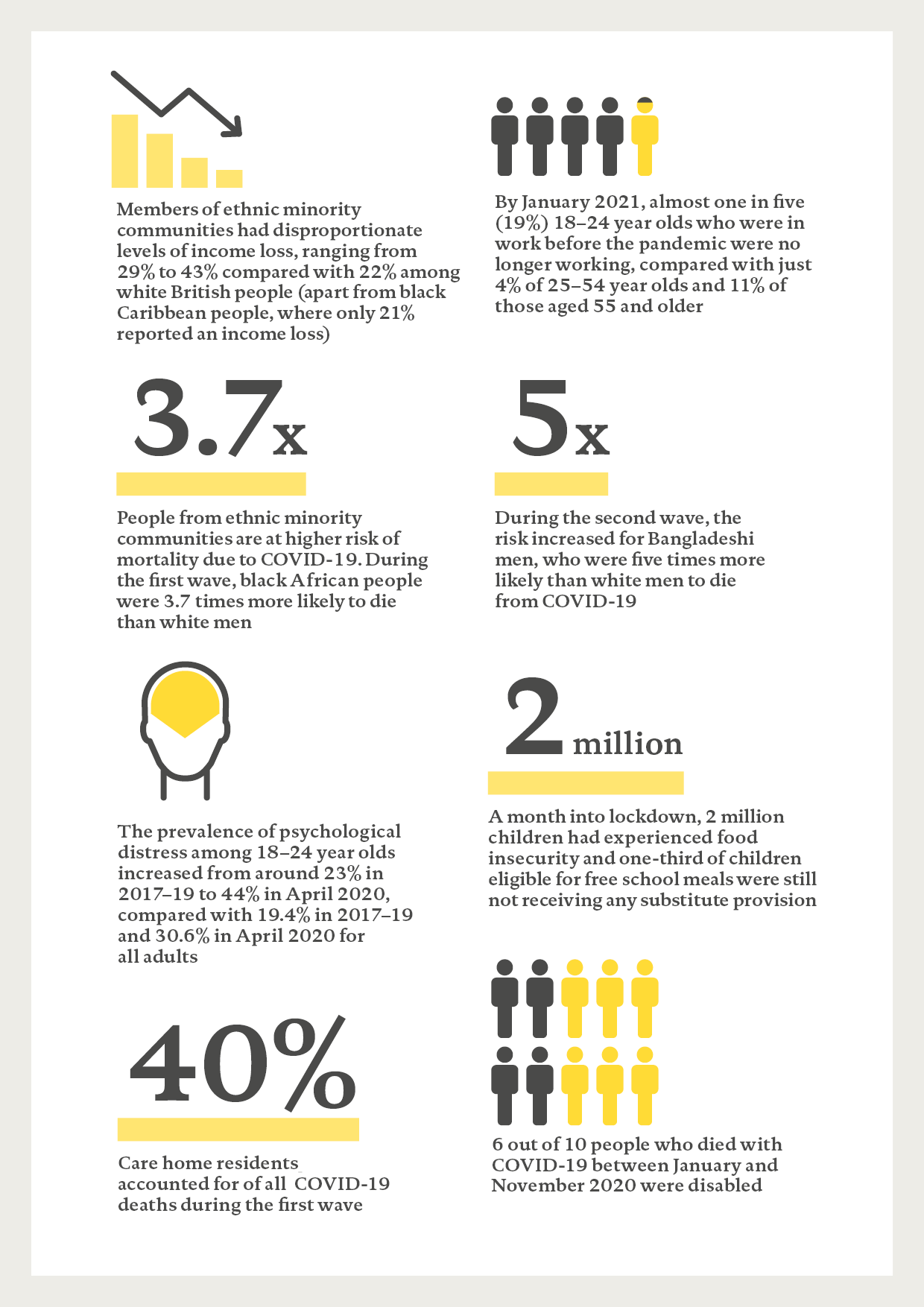

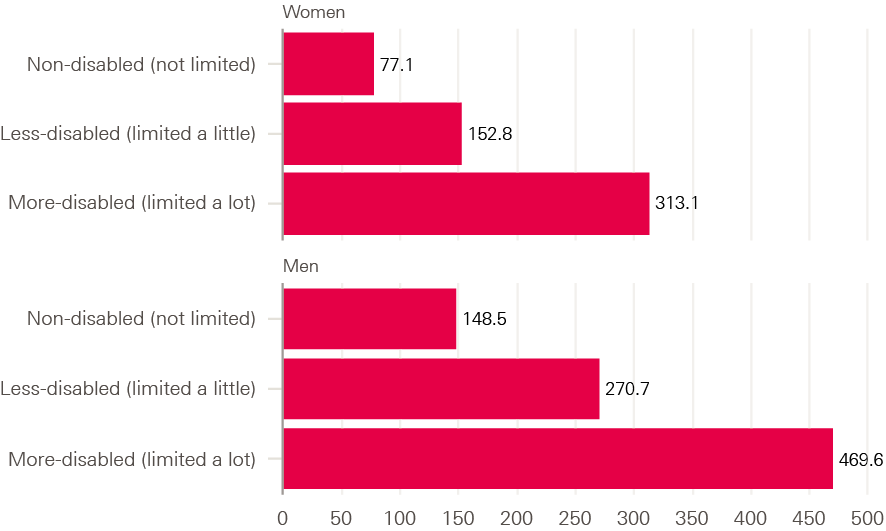

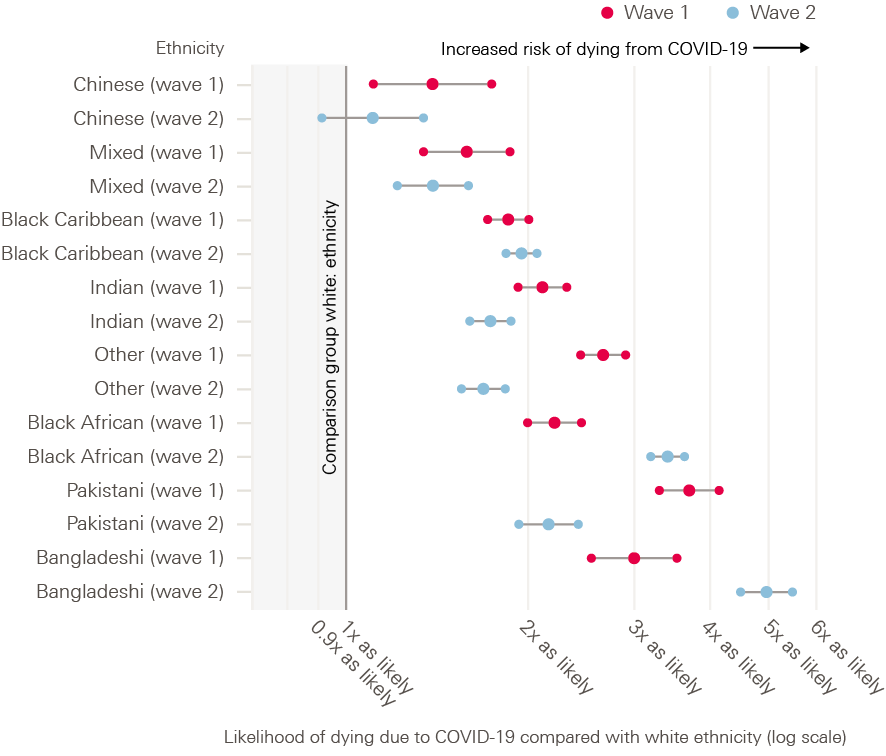

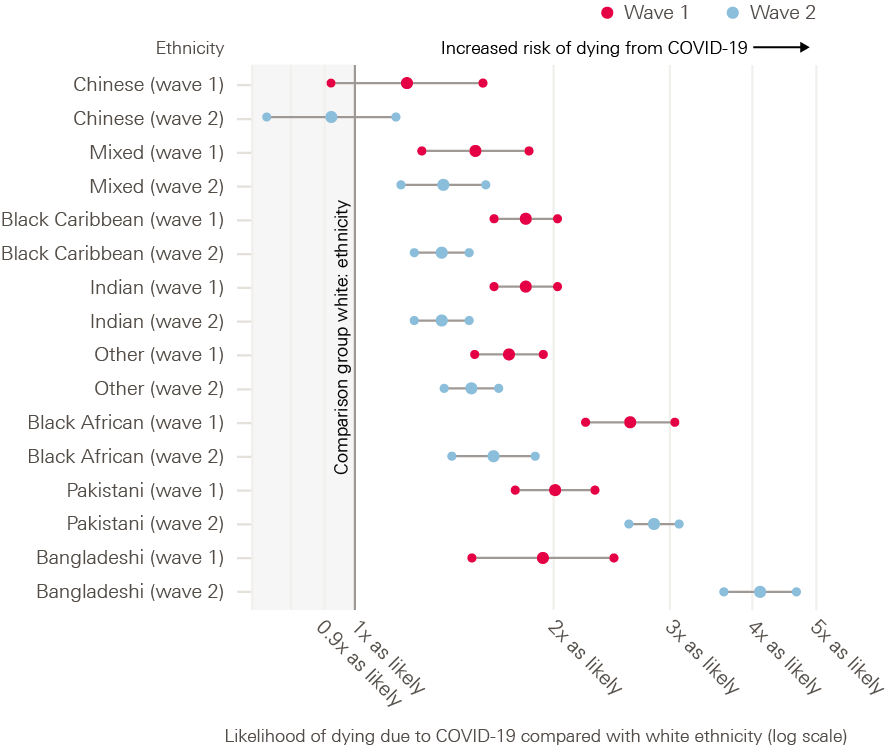

Behind these overall figures lie the unequal burdens carried by different population groups and regions. During the first wave of the pandemic, 40% of all UK deaths were among care home residents. 6 out of 10 people who died with COVID-19 between January and November 2020 were disabled. And people from ethnic minority communities had significantly higher risk of mortality – 3.7 times greater for black African men than their white counterparts during the first wave and Bangladeshi men more than five times more likely to die during the second wave.

The Health Foundation’s COVID-19 impact inquiry has drawn on a broad range of available evidence to consider two main questions:

- How were people’s experiences of the pandemic influenced by their pre-existing health and health inequalities?

- What is the likely impact of actions taken in response to the pandemic on the nation’s health and health inequalities – now and in the future?

It is beyond our intended scope to propose specific policy recommendations. But the findings from this inquiry can direct policymakers at national and local level to some core issues that need attention as they take the recovery forward.

COVID-19 mortality and the actions taken to reduce it

Government restrictions have suppressed the spread of the virus and saved lives. National and tiered lockdowns, PPE provision, self-isolation measures, and the vaccine programme have moved us towards recovery.

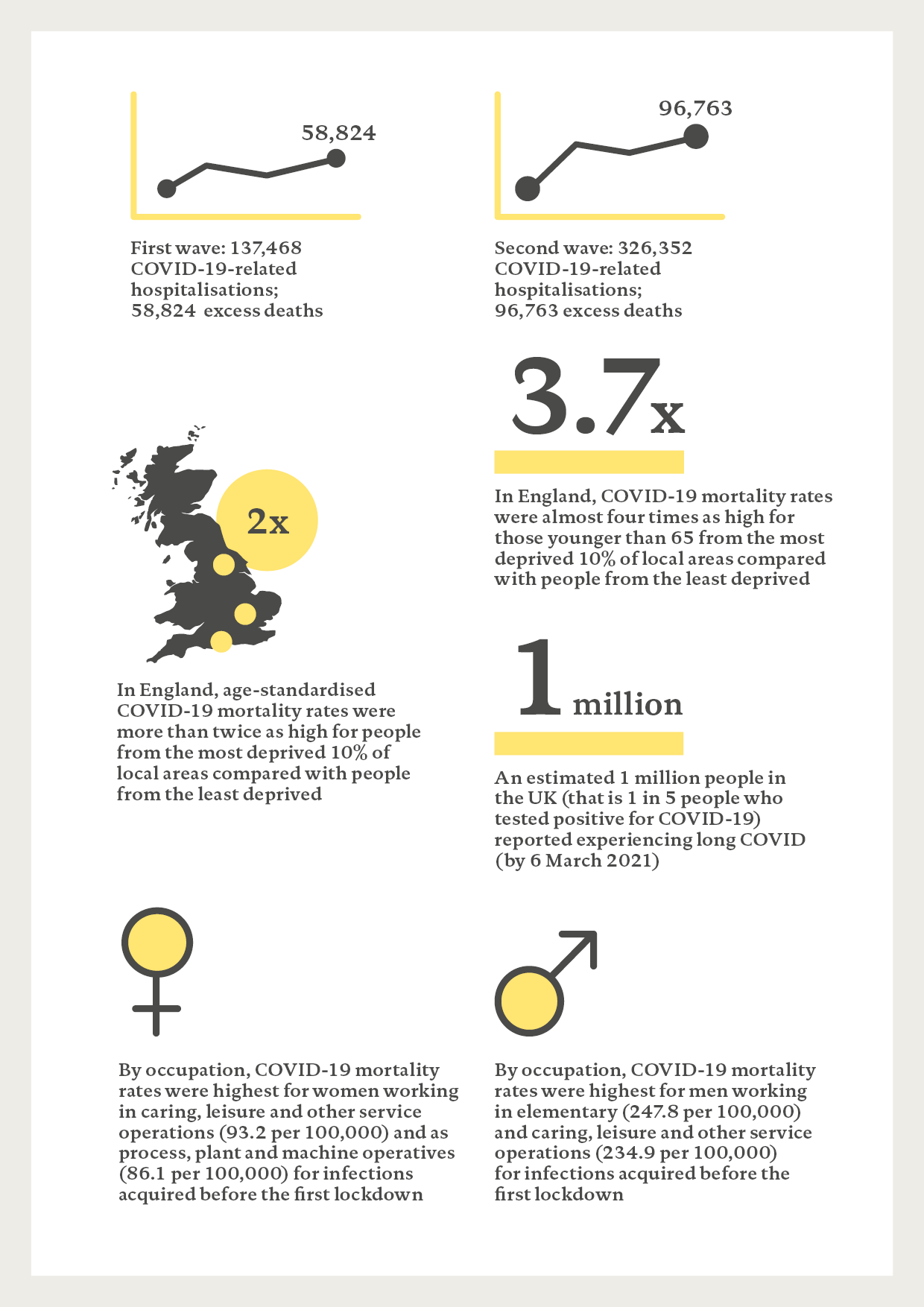

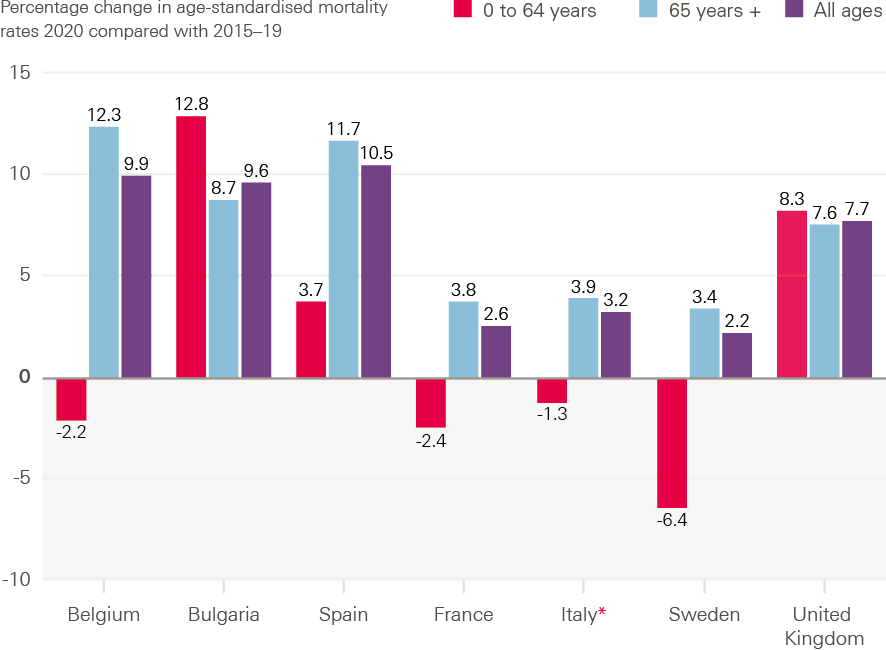

Despite these actions, the UK had the fourth highest excess deaths of OECD countries in 2020. Excess deaths for people younger than 65 were the second highest in Europe after Bulgaria. The UK’s experience was worse during the second wave (326,352 COVID-19-related hospitalisations and 96,763 COVID-19 deaths in this wave alone).

Several factors have influenced variations in the impact of COVID-19 across different countries. The single biggest factor was the timing of pandemic restrictions as these influenced levels of exposure to the virus. Population density and high levels of regional and international travel accelerated spread in the UK ahead of restrictions.

Poor underlying health also accounted for differences in excess mortality among countries – particularly in the outcomes for people younger than 65. Countries with the greatest improvement in healthy life expectancy over the previous decade experienced lower excess mortality during the pandemic. Conversely, countries with the highest levels of disability-adjusted life years lost to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and chronic respiratory disease had higher mortality rates.

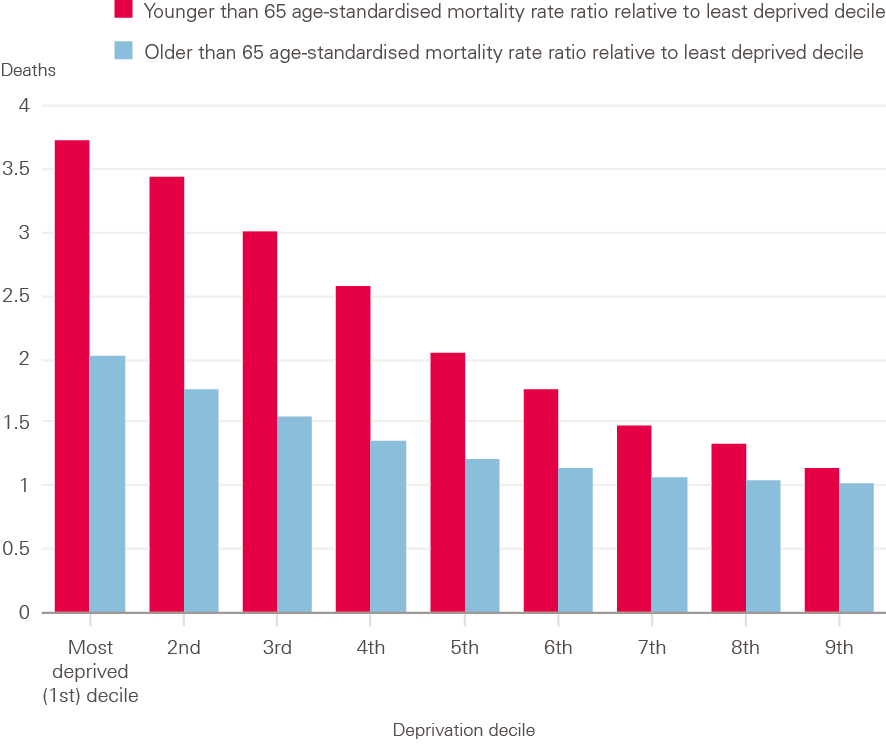

Certain socioeconomic factors were also associated with an increased risk of transmission. In England, COVID-19 mortality rates were more than twice as high for people from the most deprived 10% of local areas compared with people from the least deprived, and almost four times as high for people younger than 65. Pre-existing differences in health were associated with worse outcomes from COVID-19, with those aged 50–69 in the most deprived areas twice as likely as those in the least deprived areas to have at least two long-term health conditions.

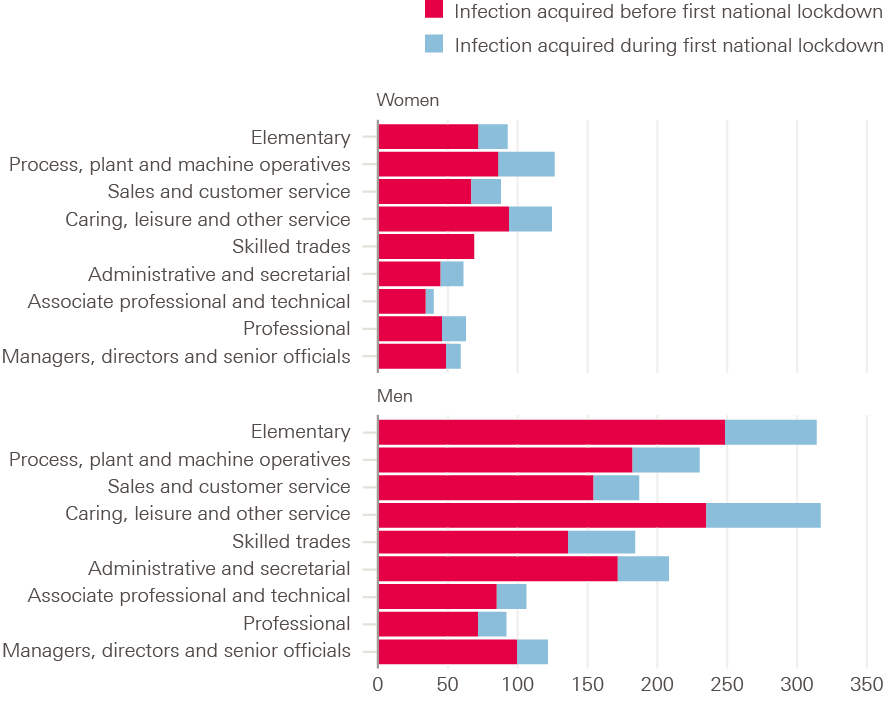

The type of work someone does and their access to financial support also shaped their risk of, and outcomes from, COVID-19. People working in elementary, caring, leisure and other service occupations had higher mortality rates, and these were higher still for men. This partly reflects poorer existing health, but also because these roles are often in sectors typified by having remained open during lockdowns or having fewer restrictive measures. For lower income workers, the inadequate level of support for sick pay was a key factor in not self-isolating.

Immediate risks to health

The immediate risks to people’s health go beyond the direct harm caused by the virus. Reprioritisation of health care services to manage COVID-19-related demand has led to increased unmet need for care. Health Foundation analysis shows that 6 million ‘missing patients’ did not seek treatment in 2020, which could mean many living with poor health for longer. In cases of acute need, such as cancer care, where treatments have been delayed, reductions in survival rates are likely.

Long COVID will limit people’s ability to return to daily life. By May 2021, an estimated 1 million people self-reported being affected by long COVID (equivalent to 1 in 5 people who tested positive for COVID-19). Women and those from more deprived backgrounds appear to be at particular risk, disrupting employment and reducing quality of life.

“In England, COVID-19 mortality rates were almost four times as high for those younger than 65 from the most deprived 10% of local areas.”

Pandemic restrictions have also affected people’s mental health through reduced social interaction, changing work conditions and loss of work and income. Although the easing of restrictions tended to improve mental health, by September 2020 there had been a sustained deterioration in mental health for a fifth of the population. Women, younger people and those facing financial hardship have fared the worst.

Access to social care services has declined despite increasing need. This will have longer term effects on the health and wellbeing of those needing care and exacerbate the growing pre-pandemic responsibilities of unpaid carers.

Reported incidents of domestic abuse increased during the first wave of the pandemic. With children out of school, child safeguarding referrals reduced. One study found a 37% decrease in referrals for child protection medical examinations between February and June 2020 than in the same period in 2019 – suggesting some children were left exposed to harm.

The vaccination programme has been crucial in reducing the spread of the virus and preventing deaths and hospitalisations with over 70 million doses of the vaccine given by 12 June 2021. Despite this there are emerging differences in access to and uptake of the vaccine. In the least deprived fifth of areas 95% of people aged 50 and older have received one dose, compared with 88% in the poorest. 67% of black Caribbean people and 78% of Pakistani people older than 50 have received one dose compared with 94% of white people. These threaten to exacerbate existing health inequalities as well as the continued risk posed by existing and emerging variants.

Future risks to health

With large parts of the economy shut down and people required to stay at home, the government implemented unprecedented economic measures to provide support for individuals, families and businesses (such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme) and increased existing financial support (such as the £20 weekly Universal Credit uplift). Despite the scale of action, 28% of adults saw their family finances deteriorate by September 2020. Many families had to rely on savings or debt to get by with more than half (54%) of those in the poorest fifth seeing their debts rise compared with 31% of the wealthiest fifth.

Although there were early signs of labour market recovery in spring 2021, an extra 2.8 million people were out of work in May 2021 than before the pandemic, and the end of the furlough scheme in autumn is likely to mean unemployment rises. Assuming the £20 a week uplift to Universal Credit ends in September 2021, around 6 million families will experience a drop in income.

Experiencing financial strain or periods of unemployment – resulting in lack of status, structure and income – are associated with poorer physical and mental health. As temporary support measures end, the pandemic risks further eroding people’s health through a decline in living conditions and an increase in poverty.

The loss of education during the pandemic also risks widening the gap in future health outcomes. The cohort of children and young people who have missed periods of education could lag behind pre-pandemic cohorts. The loss of education has also not fallen evenly, with children from more disadvantaged backgrounds having experienced a greater deterioration in their educational outcomes.

But the risks to health identified in this report are far from inevitable and can be addressed through a fair recovery.

Ensuring a healthy recovery

The government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda – and its associated funding for local government – creates an opportunity to ensure this recovery is managed better than that following the 2008 financial crisis and creates a more resilient and fairer society.

With poor health estimated to cost the UK economy £100bn a year in reduced productivity, the much-needed economic recovery will also require a recovery in the nation’s health.

Immediate action is needed to address the harm caused by the pandemic – tackling the health care backlog, protecting family finances and ‘catching up’ on education. There need to be greater protections for low-paid workers as well as schemes and targeted support for people whose mental health has deteriorated to get back into work.

Over the longer term, resilience can be built through investment to create good-quality jobs in areas with historically low employment, as well as those hardest hit by the pandemic. Businesses can design better quality jobs and individuals can continue to help strengthen local communities. Weaknesses in the welfare state need to be addressed to provide an adequate safety net that supports people through income and health shocks. Public services will require investment and to be redesigned to put prevention first.

The nation’s health has frayed over the past decade and this has contributed to the UK experiencing some of the poorest global outcomes from the COVID-19 pandemic. Ensuring a recovery that improves health – as well as the economy – will require a cross-government health inequalities strategy with clear targets for improvement and a regular, independent assessment of the nation’s health laid before parliament.

* Excess deaths measure additional deaths over a time period compared with the number of deaths usually expected. We measure the deaths caused by the pandemic in excess deaths instead of registered COVID-19 deaths due to discrepancies in the way COVID-19 deaths are recorded.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on people’s health and their livelihoods. By mid-March 2021, the pandemic had led to 119,000 excess deaths in the UK and in 2020 caused a 9.9% drop in GDP. The UK government and devolved governments have taken far-reaching action in attempts to suppress the virus: schools closed, routine health care suspended, and businesses and community facilities shut down.

People’s experiences of the pandemic have varied greatly. Not everyone faced the same risk of exposure to the virus nor equivalent severity in health outcomes. The measures taken to suppress the virus have affected people’s lives and livelihoods differently – with both immediate and longer term consequences for people’s health and wellbeing.

Although COVID-19 has been challenging for governments around the world, the UK entered the pandemic with life expectancy stalling for the first time in a century. A month before the first national lockdown, The Marmot Review 10 Years On – funded by the Health Foundation – showed that life expectancy had gone into reverse for the most socioeconomically deprived communities, revealing a growing gap in health between wealthy and deprived areas.

This report explores how the same factors contributing to this widening of health inequalities exposed the UK to a high death toll and reduced people’s ability to deal with the subsequent economic shock. Drawing on an extensive body of evidence, this report identifies what has driven such outcomes during the pandemic.

Scope and structure of this report

The factors shaping the UK’s overall experience of the pandemic are complex and multifaceted, and the pandemic is still ongoing. The COVID-19 impact inquiry provides an initial assessment of the effects of the pandemic using evidence available up to May 2021.

The inquiry set out to answer two key questions:

- How were people’s experiences of the pandemic influenced by their pre-existing health and health inequalities?

- What is the likely impact of actions taken in response to the pandemic on people’s health and health inequalities – now and in the future?

The inquiry did not set out to formulate specific policy recommendations but does highlight the need for action in two key areas to ensure the recovery creates a more resilient society that improves the nation’s health: immediate action to address the harm caused by the pandemic and prevent longer term scarring effects; building resilience for the longer term.

The COVID-19 impact inquiry

The Health Foundation launched this inquiry in October 2020 to gather, analyse and synthesise evidence and insight from an extensive range of sources, including:

- submissions received from around 75 charities, patient representative groups and community organisations, through an open call and an in-house evidence review of an additional 600 papers

- commissioned work to address gaps in the literature relating to the experience of specific population groups

- a literature review of existing qualitative evidence, to understand the public experience of the pandemic

- stakeholder meetings focused on disability and digital exclusion, as well as discussions and analyses of the impacts of the pandemic across the four UK nations

- in-house Health Foundation data analysis.

Other sources of data were excluded, such as studies with a low sample size or qualitative data that could not be triangulated by other evidence. The literature review covers evidence up to May 2021 and more detail of this review and the analysis is available in the separate technical supplement.

Box 1: The Expert Advisory Panel

The inquiry has been guided and informed by an advisory panel with expert members from across the areas of inequalities, economics and the wider determinants of health. The members are:

- Dame Clare Moriarty (Chair)

- Lord Victor Adebowale CBE

- Professor James Banks

- Yvonne Coghill CBE

- Professor George Davey Smith FRS

- Sarah Davidson

- Fozia Irfan

- Polly MacKenzie

- Professor Sir Michael Marmot

- Auriol Miller

- Professor James Nazroo

- Dr Vanessa Pinfold

- Yusuf Qureshi

- Matthew Whitaker

COVID-19 health outcomes

Summary

During the first wave, the UK had the fourth highest rate of excess deaths out of 33 OECD countries behind Spain, Mexico and the USA. Despite government measures to supress the virus, the UK experienced higher hospitalisations and excess deaths during its second wave. It also had one of the highest excess mortality rates among those younger than 65 in Europe.

The single biggest factor influencing differences in COVID-19 mortality between countries was the timing of restrictions. The virus spread throughout the UK before restrictions were applied due to higher levels of travel within and to the UK. Underlying population health also accounted for some of the variation in excess mortality between countries.

In the UK certain groups experienced disproportionate levels of exposure and deaths due to the virus. These included: older people, people from ethnic minority communities, disabled people and people working in certain occupations, including some keyworker roles.

Occupation, living conditions and the ability to access financial support affected risk of exposure to COVID-19. Low rates and coverage of statutory sick pay, and difficulty in accessing isolation payments reduced people’s ability to self-isolate and increased exposure. Being able to work from home reduced the exposure risk.

Once exposed, people’s pre-existing physical and mental health made them more vulnerable to severe outcomes. People with pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, cancer, respiratory disease and underlying mental health conditions were at increased risk of death from COVID-19.

In England, for people younger than 65, the COVID-19 mortality rate for the 10% living in the most deprived areas is almost four times that of those in the least deprived areas. This partly reflects the poorer health of people living in more deprived areas.

The vaccination programme has been crucial in preventing many deaths and hospitalisations. Despite this some groups have lower access to and uptake of the vaccine.

COVID-19 health outcomes summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound consequences for the health of people in the UK. Most directly – and visibly – through the numbers of deaths attributed to COVID-19 and those who have experienced severe symptoms. As explored in this section, the UK’s high COVID-19 death toll reflects a range of different factors. While some factors relate to how the pandemic was managed – such as the timing of lockdown measures – others reflect pre-existing aspects of the structure of UK society and the economy, such as the wide disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates for those younger than 65.

COVID-19 outcomes in the UK

COVID-19 was first detected in the UK in January 2020 with the first known death occurring at the beginning of March 2020. On 23 March, the UK government mandated a nationwide lockdown requiring certain businesses to close and for people to only leave their homes for essential purposes. By this time there were already 938 deaths recorded and around 5,000 hospitalisations attributed to COVID-19. Most of these deaths had occurred in England (876), with Wales (24), Scotland (29) and Northern Ireland (9) recording fewer deaths.

Box 2: COVID-19 waves and mortality

Where possible, this report uses the Office for National Statistics (ONS) definition of first and second waves. The first wave refers to the period between 24 January and 11 September 2020. The second wave refers to the period from September 12 2020. Where our analysis diverges from this definition, this is clearly flagged.

A measure of excess mortality for COVID-19 deaths in the first wave is used – this is the number of deaths in a given period over and above the number expected, such as the average number recorded in the same week of the past 5 years. This was the international gold standard used to measure mortality during the pandemic, and the measure we used for international comparisons.

This is more reliable than measuring cases of COVID-19 because testing and the reporting of deaths vary between countries. This also matters in comparing between waves in the UK, given testing was less available during the first wave and conducted mainly for hospitalisations, leaving high numbers of potential infections uncounted.

For the second wave, COVID-19 deaths are a more accurate measure of COVID-19-related mortality in the UK. This is due to increased testing and because excess mortality was reduced due to lower numbers of deaths than usual from flu during winter 2020–21.

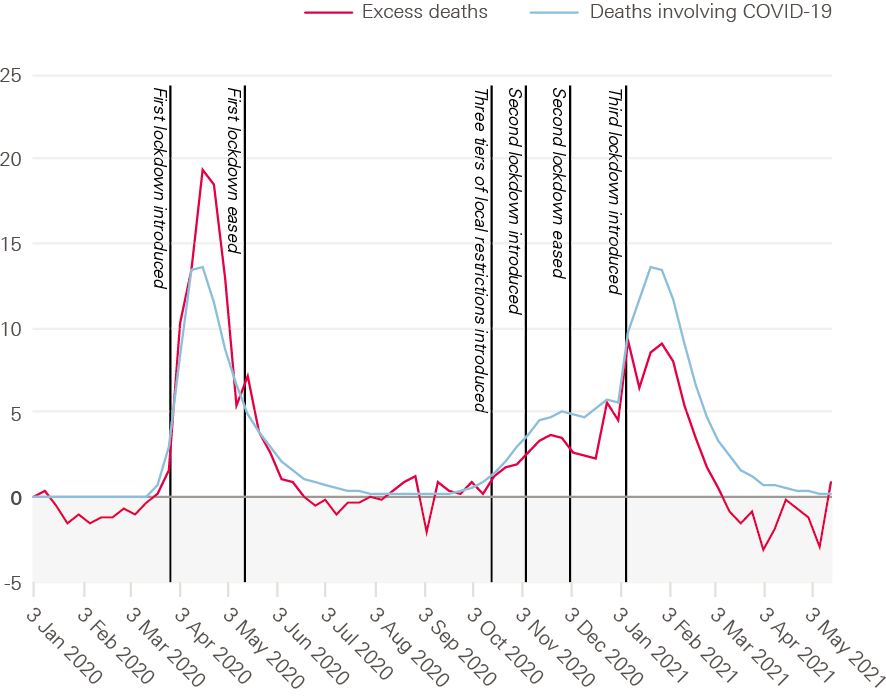

The nationwide lockdown saved thousands of lives but by the end of the first wave the UK had experienced 137,466 hospitalisations due to COVID-19 and 58,824 excess deaths. With tight restrictions in place, the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths began to fall from mid-April 2020. By the end of June, weekly deaths were back to levels consistent with previous years.

As restrictions eased in the summer, COVID-19 cases again began to rise, leading to a second wave. Between 12 September 2020 and 30 April 2021, the UK experienced a further 96,763 COVID-19 deaths and 326,352 hospitalisations. The second wave was a more prolonged outbreak.

Figure 1: Excess deaths and deaths involving COVID-19 by week registered, per 100,000 people, UK, January 2020 to June 2021

Source: Health Foundation analysis of ONS, Weekly provisional figures on deaths registered in England and Wales; National Records of Scotland, Deaths involving coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland, Weekly data on Births and Deaths in Scotland; NISRA, Weekly deaths bulletin; Mid-year population estimates via NOMIS.

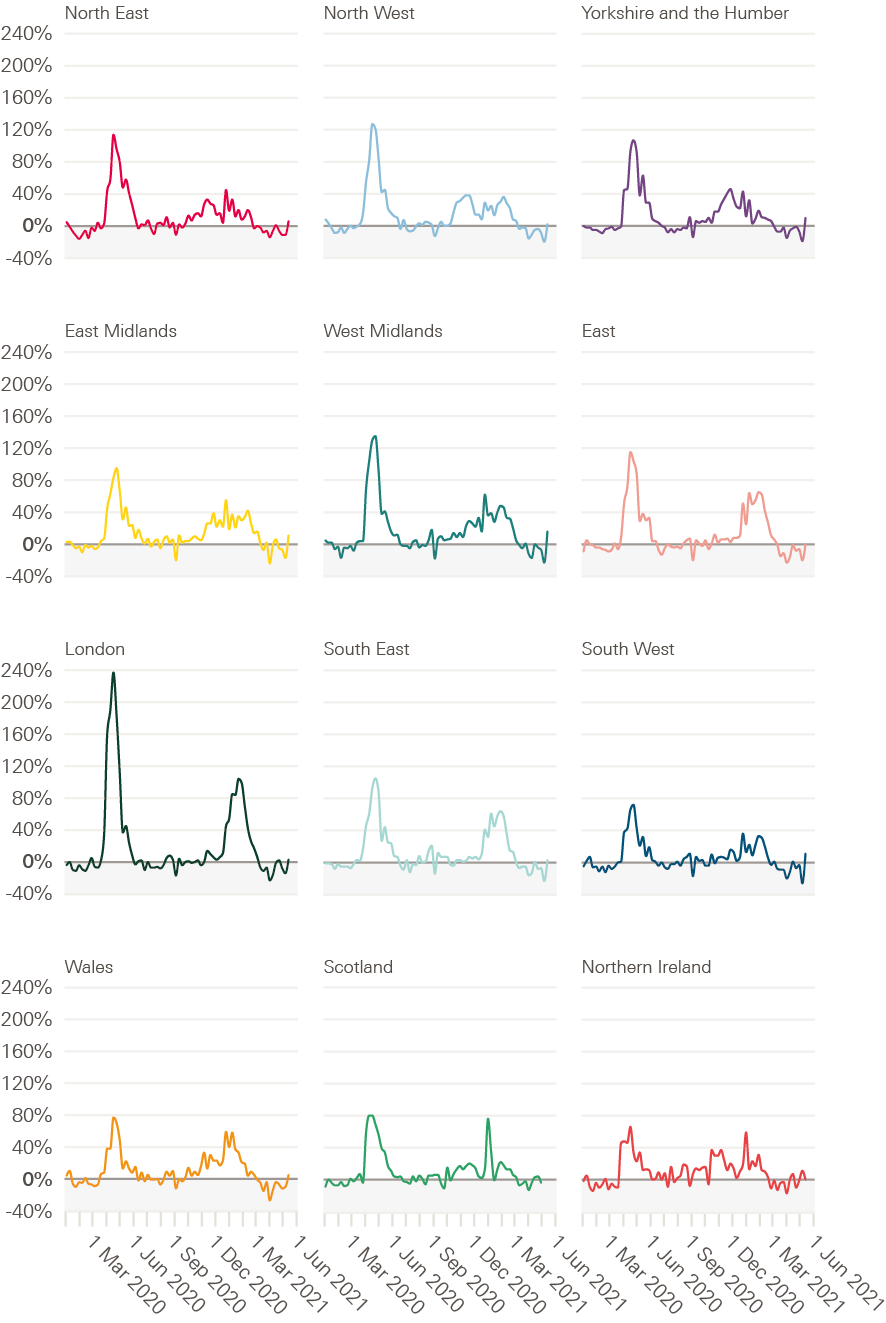

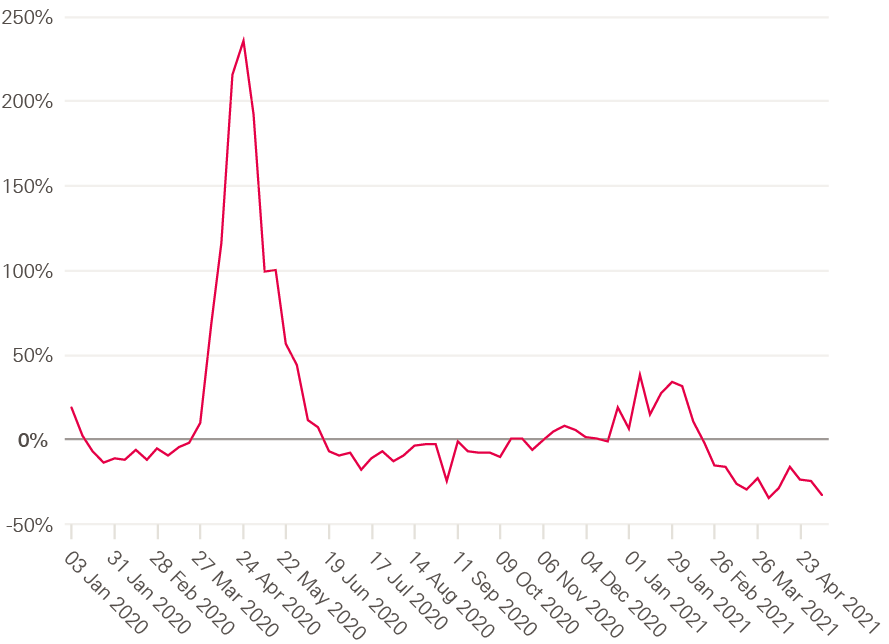

Experiences of COVID-19 have varied across the UK, from one nation to the next and between different regions within nations. England had the highest excess deaths during the first wave. In the second wave, the rates were more similar across the four nations except for Northern Ireland, which had a slightly lower level of excess deaths.

At first, each UK nation imposed the same rules. But over time these varied – in timing and stringency – as measures were eased at the start of June 2020. However, by the end of June, Leicester was back in lockdown and by August other parts of the country had returned to stricter measures. Between the end of the first lockdown (July 2020) and the beginning of the second lockdown (November 2020), some regions and countries in the UK had considerably higher levels of excess mortality. Northern Ireland had 36 excess deaths per 100,000, and the north east and north west of England had 19 per 100,000. London had fewer excess deaths than average, and the south west had 1.6 per 100,000, highlighting the regional variation in outbreaks during this period.

Figure 2: Excess deaths as a share of expected deaths by week registered, for regions and countries of the UK, January 2020 to June 2021

Source: Health Foundation analysis of ONS, Weekly provisional figures on deaths registered in England and Wales; National Records of Scotland, Deaths involving coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland, Weekly data on Births and Deaths in Scotland; NISRA, Weekly deaths bulletin; Mid-year population estimates via NOMIS.

In the north of England as well as the East Midlands, deaths began to increase from October 2020 compared with November/December in London and parts of the south of England. These regional variations and tiered restrictions continued until a new national lockdown was imposed in January 2021.

“Across the 33 countries in the OECD with comparable data, the UK had the fourth highest excess mortality rate during this period behind Spain, Mexico and the USA.”

Long COVID

The effect of COVID-19 on people’s health should not only be perceived in terms of hospitalisations and deaths. By May 2021, initial data showed that an estimated 1 million people self-reported being affected by ‘long COVID’ – ongoing symptoms persisting for more than 4 weeks after infection. Of these, 65% reported that persisting symptoms affected their ability to carry out day-to-day activities, including almost 20% who reported these activities had been limited a lot. People with a pre-existing, activity-limiting health condition, women, workers in the health and care sectors and those from more deprived backgrounds have reported higher incidences of long COVID.

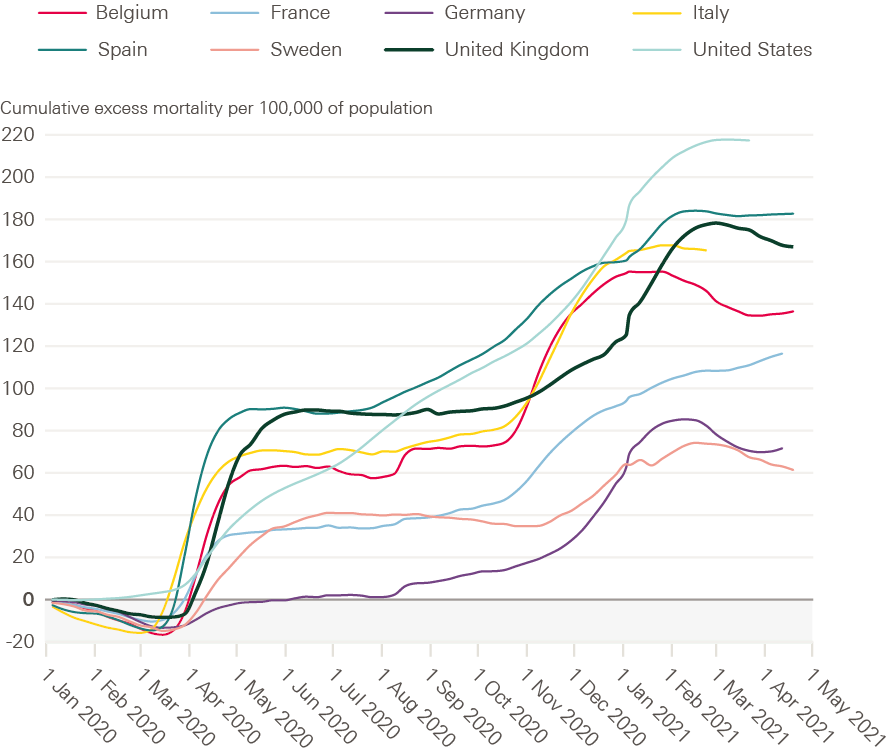

Comparing UK COVID-19 outcomes internationally

Outcomes from COVID-19 during 2020 – measured by excess deaths – were significantly worse in the UK than in most other comparable OECD countries. Across the 33 countries in the OECD with comparable data, the UK had the fourth highest excess mortality rate during this period behind Spain, Mexico and the USA. In spring 2020, the UK had a higher peak in the rate of excess deaths than neighbouring or similar countries other than Spain (Figure 3).

In the autumn, excess deaths began to rise and then fall again following short-term restrictions in November, but then rose rapidly through December and January 2021. The 82,305 COVID-19 deaths between 28 November 2020 and 30 April 2021 can be attributed partly to the rapid spread of the alpha variant and a failure to introduce lockdown measures sooner. Few other countries experienced the level of excess deaths that the UK saw at the peak of its second wave.

Restrictions began to be eased again on 12 April 2021. Deaths have remained low in the UK following tight restrictions and the introduction of the vaccination programme. But the threat of emerging variants that may be more transmissible or resistant to existing vaccines remains.

Explaining the differences in COVID-19 outcomes internationally

The single biggest factor in the extent to which COVID-19 spread in the UK compared with other countries is the timing of lockdowns and stringency of restrictions. Higher levels of regional and international travel, increasing burden of disease and worsening social conditions also played a role. Once the virus had spread the extent to which different groups were affected within the UK reflected variations in underlying health and socioeconomic factors that increased risk of exposure and worse outcomes.

Figure 3: Cumulative excess mortality for select countries, January 2020 to May 2021

Source: Health Foundation analysis of Our World in Data excess mortality data, population data via OECD Stat for 2018.

Timing of lockdowns and travel

Differences in policy interventions were more important than socioeconomic variations in explaining the varying death rates among OECD countries. One study points to timing of lockdowns accounting for around 40% of the international variation in deaths – highlighting the importance of policy responses in suppressing the spread of the virus.

The extensive spread of the virus observed in the UK reflects three factors:

- COVID-19 entered the country in a number of regions over a similar period of time

- the UK is more densely populated than many developed countries,

- the relatively high level of travel between different UK regions, for instance there were more than 1.7 billion domestic trips in 2019 (versus 260 million in France).

The virus arrived and spread in different places in the UK, leading to excess deaths across all regions. In other countries, the spread of the virus and deaths tended to be isolated to specific regions. For example, in Italy only three northern regions experienced high excess mortality outside of the main cities.

An ageing population and poorer underlying health

The total number of excess deaths during the first wave was highest for older age groups, with 41% of all deaths among those aged 85 and older. Once the virus had spread, the age and health of the UK population (including underlying health conditions and comorbidities) played a role in the severity of outcomes.

The UK has an ageing population, so could expect more deaths than countries with a younger age profile. But deaths among older age groups were far higher in the UK than other countries even though its proportion of people aged 80 and older is below average for a developed country. As healthy life expectancy improvements have not kept pace with life expectancy in the UK, people are living more years in poor health – particularly in older age. This could have led to greater vulnerability to COVID-19.

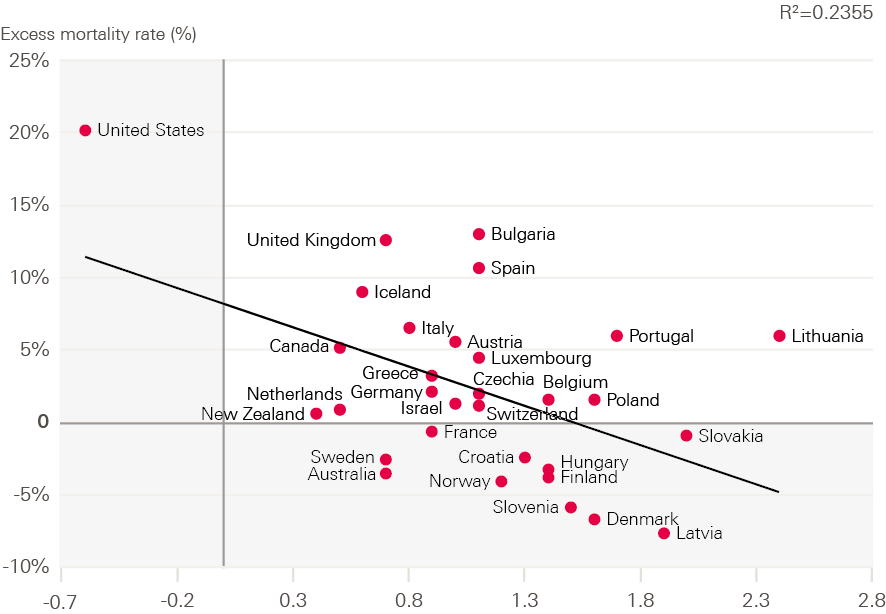

While there appears to be little relationship between pre-existing levels of life expectancy or healthy life expectancy and excess deaths from COVID-19 across different countries, Figure 4 shows that greater improvement in healthy life expectancy over the past decade is associated with lower COVID-19 mortality. Countries with the greatest improvements in healthy life expectancy in the previous two decades, such as Latvia and Slovenia, experienced lower excess mortality during the pandemic. A similar pattern holds for life expectancy improvements.

Improvements in healthy life expectancy are a meaningful measure of broader and historical social conditions because factors such as adequate income, good-quality jobs and housing are necessary ingredients for good health. The decline in improvement in healthy life expectancy partly reflects the erosion of these social conditions in the UK in the decade preceding the pandemic – affecting certain groups to a greater extent. This reduced the population’s opportunities for good health and is highly likely to have weakened resilience to COVID-19.

Figure 4: Change in healthy life expectancy at birth, 2010–2019 compared with excess mortality as a share of expected deaths during 2020, for people aged younger than 65, selected OECD countries

Source: The Human Mortality Database, Short-term Mortality Fluctuations (STMF) data series; WHO Global Health Observatory data repository.

Note: Greece and Germany calculations are based on 2016-2019 data. Data from 2000 to 2018 are final and results for 2019 and 2020 are provisional. Data for the last 3 weeks of 2020 are estimated. Data for 2020 and 2021 are preliminary. Expected deaths are an average of deaths between 2015 and 2019.

Increasing burden of disease in the UK

Research within the UK, and internationally, shows that certain underlying health conditions increase risk of more severe outcomes from COVID-19. For example, UK adults with diabetes were 1.31–1.95 times more likely (depending on blood sugar levels) to die than those without diabetes, after adjusting for age, sex and other health conditions. Similarly, those with dementia, obesity, cancer, respiratory disease, reduced kidney function or COPD had an increased risk of mortality., In the years leading to the pandemic, the UK experienced declines in health – particularly in the conditions associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes. In 2016, 27.8% of adults in the UK were obese, the highest in Europe. Prevalence data from the Global Burden of Disease study also show that the UK has higher age-standardised prevalence of asthma, COPD, chronic respiratory conditions and diabetes. It is lower for stroke, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney conditions. In the decade to 2019, diabetes prevalence increased faster in the UK than in the EU.

Table 1: Age-standardised prevalence of certain health conditions associated with COVID-19 outcomes, UK and EU, 2019 and change since 2009

|

UK age-standardised prevalence 2019 |

EU age-standardised prevalence 2019 |

Difference |

Change in the UK since 2009 |

Change in the EU since 2009 |

|

|

Cancer |

2.2% |

2.1% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

0.0% |

|

Diabetes |

9.4% |

6.5% |

2.9% |

1.9% |

0.9% |

|

Chronic kidney disease |

5.7% |

6.6% |

-0.9% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

4.3% |

3.2% |

1.1% |

-0.1% |

-0.1% |

|

Chronic respiratory conditions |

13.3% |

8.8% |

4.5% |

-1.1% |

-0.5% |

|

Cardiovascular disease |

6.1% |

6.6% |

-0.5% |

0.1% |

-0.1% |

|

Asthma |

10.1% |

6.1% |

4.0% |

-1.2% |

-0.5% |

|

Stroke |

0.7% |

0.9% |

-0.1% |

-0.1% |

-0.1% |

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease Study, 2019 via GBD Results Tool.

People with underlying mental health conditions have also had worse COVID-19 outcomes. Evidence from the UK Biobank study between 31 January and 26 July 2020 found that after adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, BMI, smoking status and certain comorbidities, people with existing psychiatric disorders were 2.0 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those without. The risk ranged from 1.2 for substance misuse to 3.5 for psychotic disorders. People with more than one psychiatric diagnosis had an even higher risk of dying from COVID-19.

A range of factors contribute to worse COVID-19 outcomes among those with mental health conditions:

- higher prevalence of other underlying health conditions, such as diabetes

- greater likelihood of living in poor living environments

- difficulties appraising health information

- difficulties physically distancing or complying with social distancing restrictions

- stigma resulting in barriers to accessing health care

- differences in immune responses.

A working age population at greater risk

Compared with other European countries, excess mortality among people younger than 65 in the UK was second only to Bulgaria. Figure 5 illustrates the differences between some of these countries. More detailed analysis using data for within the UK shows the rate of excess deaths for 55–64 year olds (45–64 year olds in Scotland) was higher than for 65–75 year olds. As will be discussed further, higher COVID-19 mortality in this younger age group was determined by poorer pre-existing health due to socioeconomic deprivation, as well as increased risk of exposure.

Figure 5: Excess mortality by age, selected European countries, 2020

Source: ONS, Comparisons of all-cause mortality between European countries and regions: 2020.*

*Note: Latest data available for Italy is 30 October.

What made people more vulnerable to COVID-19 in the UK?

Underlying health and comorbidities are important factors in shaping outcomes from COVID-19, but they do not provide a complete picture of why the UK fared as it did. Other factors, such as someone’s sex, the type of work they do, where they live and their housing situation, also shaped people’s exposure and vulnerability to COVID-19.

Sex

In England and Wales 54% of COVID-19 deaths were among men. In Scotland and Northern Ireland deaths were evenly distributed among men and women., However a comparison of age-standardised rates of excess deaths shows that across 29 high income countries men were at greater risk of mortality. In England and Wales excess mortality rates were 1.5 times higher for men, 1.9 times higher in Scotland and 1.2 times higher for Northern Ireland.

“Across 29 high income countries men were at greater risk of mortality.”

Overall differences in mortality reflect that men are at a higher risk of more severe symptoms and worse outcomes. Men have higher prevalence of certain comorbidities (such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes). And there are hormonal differences too, with research showing that oestrogen can enhance the immune system while testosterone can suppress it.

Occupational risk factors

Occupation type

Among people aged 20–64, mortality differed among those working in different occupations. By the end of December 2020, the highest relative risk of mortality was for men and women working in elementary occupations, process, plant and machine operatives and in caring, leisure and other service occupations. The pattern of these COVID-19 mortality rates by occupation largely follows the pattern of all-cause mortality. This suggests that people in these occupations had poorer pre-existing health.

Figure 6 shows how risk of occupational exposure affected mortality. It compares first wave mortality rates before and after the first lockdown by occupation. Mortality rates proportionally reduced the most for people more likely to be able to work from home, or for those who tended to work in sectors that shut down.

People working in social care had a significantly higher rate of death compared with those working in health care by December 2020. For men, the death rate in health care was 44.9 per 100,000 people, rising to 79.1 per 100,000 for nurses, compared with 109.9 per 100,000 in social care. For women, the death rate for health care was 17.3 per 100,000, rising to 24.5 for nurses, and compared with 47.1 in social care.

Figure 6: Age standardised mortality rates for deaths related to COVID-19 among 20–64 year olds by occupation and sex, England and Wales, March to June 2020

Source: ONS, Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, before and during lockdown, England and Wales: deaths registered between 9 March and 30 June 2020.

A study from Scotland using national data on health care workers for the period 1 March to 6 June 2020 found that patient-facing workers were 3.3 times more likely to be admitted to hospital for COVID-19 than non-patient-facing workers, after adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation and comorbidity. Household members of patient-facing workers were also 1.79 more likely to be admitted.

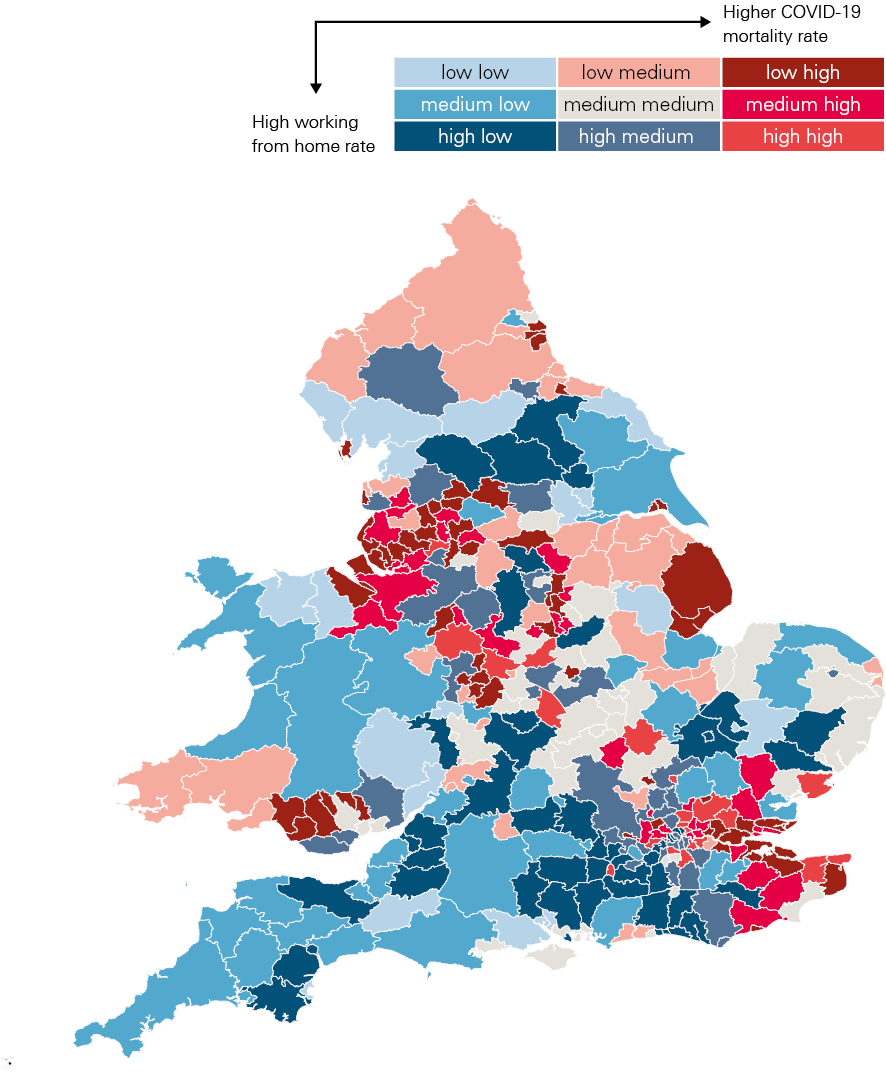

Figure 7 highlights the relationship between the ability to work from home and COVID-19 mortality for those younger than 65 across local areas in England during the second wave. Areas with low rates of homeworking and high mortality rates are shown in dark red; areas with high rates of homeworking and low mortality rates are shown in dark blue. The pattern suggests that those able to work from home were able to limit their exposure to the virus and subsequently their risk of mortality. Some areas, however, had high rates of homeworking and COVID-19 mortality among those younger than 65. In London and the south east in particular this partly reflects exposure to the alpha variant in late 2020. More rural areas and the south west tended to have low rates of both.

Figure 7: Mortality rates for deaths due to COVID-19 among those younger than 65 with share of workers that work from home, England and Wales, September 2020 to May 2021

Source: ONS, ad hoc requested data on COVID-19 mortality by lower tier local authority and MSOA by age; Homeworking in the UK, work from home status.

Access to financial support

The UK government and devolved governments launched several schemes to support individuals and businesses through periods of economic closure and reduced activity. This included the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. By May 2021, over 11 million jobs had been furloughed, with people receiving financial support to replace their earnings while not being able to work.

For people going out to work, inadequate levels of sick pay led to people continuing to work even if unwell or exposed to COVID-19. UK statutory sick pay covers only a quarter of the average worker’s earnings and 2 million of the lowest paid workers are ineligible. Additional self-isolation payments of £500 were introduced but access to the scheme was limited – between September/November 2020 and 15 January 2021, only one-third of people applying for isolation payments were successful.

Financial incentives to keep working are also strong, with UK unemployment benefits replacing only 12% of average wages, compared with the 50–60% replacement offered by most other western European countries. Existing UK social security design is geared towards incentivising work rather than allowing a minimum standard of living for those out of work.

The CORSAIR study, which surveyed 53,880 people aged 16 and older between 2 March 2020 and 27 January 2021, found that adherence to self-isolation was low (20.2%). ‘Going to work’ was reported as one of the most common reasons for not self-isolating.

Access to PPE

Within organisational settings, containment measures such as social distancing and access to PPE played a role in reducing deaths among key workers. For example, in the first wave there were higher deaths among social care workers compared with health care workers. Social care workers also had lower access to PPE.

In November 2020 the National Audit Office found that of the total PPE items distributed, only 14% were given to social care providers – equal to 10% of the estimated need – compared with NHS trusts, which received 81% of the PPE distributed – equal to 80% of the estimated need. The fragmentation of the social care sector further exacerbated poor coordination and lack of access to PPE for staff especially during the first wave.

Deprivation

Before the pandemic, women living in England’s most socioeconomically deprived 10% of local areas were already expected to live 19 fewer years in good health than those in the least deprived 10%. COVID-19 mortality also follows a similar pattern in deaths by deprivation seen before the pandemic.

For people younger than 65, the COVID-19 mortality rate for the 10% living in the most deprived areas is almost four times (3.7) that of those in the least deprived areas (Figure 8). This partly reflects the poorer health of people living in more deprived areas. 50–69 year olds living in the 10% most deprived areas are more than twice as likely to have two or more long-term conditions, with a similar risk differential for diabetes and chronic lung conditions. Differences in occupation (for those in work) and housing conditions also increased risk of exposure to the virus in areas with greater deprivation.

Figure 8: Age-standardised mortality rates for deaths due to COVID-19, deprivation decile relative to the least deprived decile by age, England, March 2020 to May 2021

Source: ONS, ad hoc requested data on COVID-19 mortality by lower tier local authority and MSOA by age and MySociety IMD2019 Maps Local Authority MSOA-level file.

Housing

Going into the pandemic, one in three households in England (32% or 7.6 million households) had at least one major housing problem relating to overcrowding, affordability or poor-quality housing. These factors increase exposure to poor living conditions, reduce financial resilience, and exacerbated susceptibility to COVID-19 through overcrowding.

In 2019/20, the rate of overcrowding in the private and social rented sectors in England was at its highest recorded, with 9% of social renters and 7% of private renters living in overcrowded accommodation.

Household size increases the risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality, with one study finding that household size increased the odds of a positive test by 9%. Another study found that households with nine or more residents had more than five times the risk of deaths compared with single-occupant households.

Multigenerational households are also associated with higher rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality. For example, for women aged 65 and older, the risk of mortality if living in a multigenerational household with children was 1.2 times that of people living with another adult. Research also shows that the proportion of people aged 70 and older living with people of working age within a local authority explains some of the variation in COVID-19 cases across England – suggesting the risk of exposure was greater and that those of working age may not have had the space to self-isolate in their own homes.

The COVID-19 vaccination programme

The NHS vaccination programme has been a crucial intervention in suppressing COVID-19’s spread, saving lives and marking the beginnings of recovery in the UK. The initial rollout prioritised reducing mortality. As age is a key predictor of COVID-19 mortality, the focus was on making sure the oldest people were vaccinated first along with health and social care staff and those with underlying health conditions. By 30 April 2021, almost 35 million people in the UK had received their first dose and almost 15 million had received both doses.

Analysis by Public Health England found that the vaccination programme had prevented 33,000 hospitalisations among people aged 65 and older, and 11,700 deaths among people aged 60 and older in England to the end of April 2021.

Nevertheless, there are emerging inequalities in access to and uptake of the vaccine. Figure 9 shows that by 12 April 2021, fewer people in socioeconomically deprived areas, people from ethnic minority groups, or those for whom English is not their main language have been vaccinated – despite the pandemic disproportionately affecting these groups. Only 88% of people aged 50 and older in the poorest areas had received a first dose, compared with 95% in the least deprived. Innovative approaches are being applied by local councils to close this gap, including providing information and training to community and faith leaders, interactive webinars and follow-up phone calls with people not taking up vaccinations.

Ensuring a fair recovery across all areas and groups will require concerted local and national efforts to mitigate these differences in vaccine access and uptake.

Figure 9: COVID-19 vaccination rates among people age 50 and older by socio-demographic group, England and Wales, 12 April 2021

Source: ONS, COVID-19 vaccination rates and odds ratios by socio-demographic group. Data cover those aged 50 and over up to 12 April 2021.

The pandemic’s implications for wider health and wellbeing

Summary

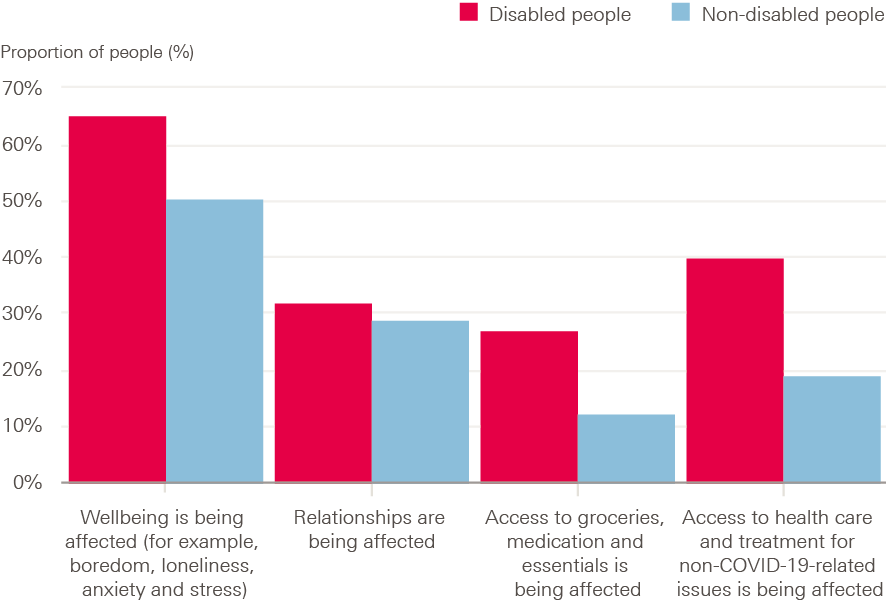

Health care services for non-COVID-19 conditions were reprioritised to manage increased demand from COVID-19. Childhood vaccinations and access to prescription medication were maintained, but reduced treatment of existing conditions has resulted in a backlog of unmet care need. People living with long-term conditions, disabled people and those shielding experienced reduced access to health services.

Access to social care services has declined despite an increasing need during the pandemic. This will have longer term effects on the health and wellbeing of those in need of services.

Mental health impacts from the pandemic are not uniform but worsened for many. One-fifth of the population had experienced a sustained increase in poor mental health by September 2020. Rates of anxiety and depression were particularly high during periods when the tightest social distancing restrictions were in place. Those facing financial hardship fared worse than others.

Domestic abuse and child protection risk increased during the first lockdown. Reported incidents of domestic abuse increased during the first wave of the pandemic. With children out of school, child safeguarding referrals reduced suggesting children were left exposed to harm.

Health risk behaviours, such as smoking and drinking alcohol, decreased during the first lockdown. However, this reduction masks an increase in these behaviours among heavy smokers and drinkers.

The measures brought in to suppress the spread of the virus have had wider implications for the health and wellbeing of people in the UK. These are less well understood and are likely to have longer term implications for the population’s health. They arise from the following main causes:

- reduced access to routine care services

- the consequences of lockdown on people’s mental health

- the consequences of lockdown on vulnerable groups

- changes in people’s health risk behaviours.

Access to health care services for non-COVID-19 conditions

Health services were reprioritised to manage the increased demand from COVID-19-related illness and to allow for new social distancing restrictions, which meant fewer patients could be treated. While this was a necessary precaution, in most sectors this has led to reduced treatment of existing conditions and a backlog of unmet care need.

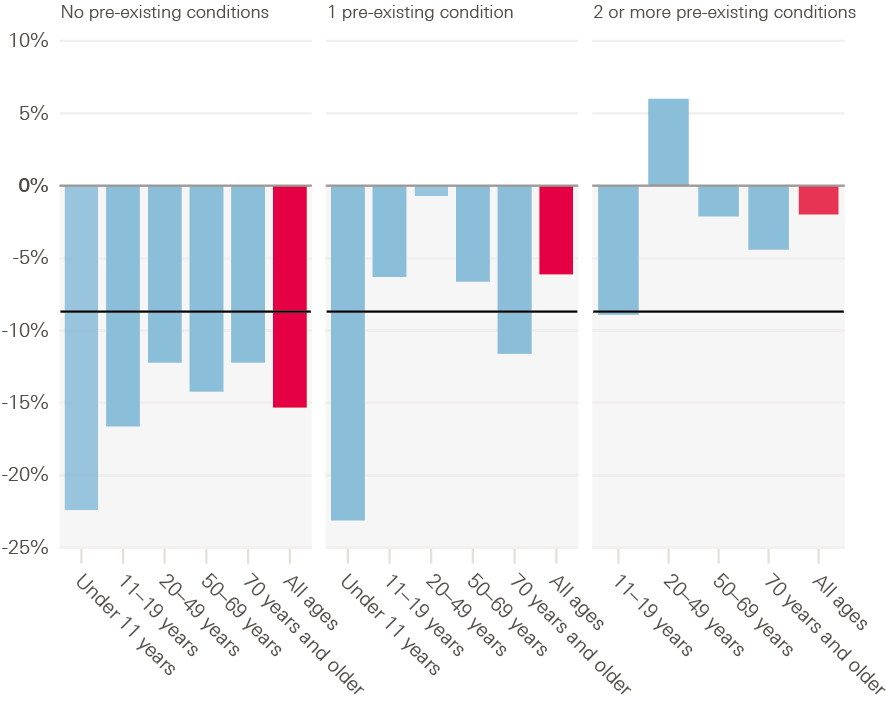

Primary care

Despite the restrictions, in April 2020, 98% of people with a long-term condition who needed prescription medications were still able to obtain them. 73% who needed treatment via a GP still received the services they needed and 65% were able to see a pharmacist. Childhood immunisations appear to have held at pre-pandemic levels in England., Health Foundation analysis shows that all regions across England saw a 30% drop in GP consultations per patient between March and May 2020. This was despite the efforts to enable online and telephone consultations. An unintended consequence of this service shift has meant that access has been more challenging for those digitally excluded or people more reliant on face-to-face services., The greatest reduction in consultations has been for patients without a pre-existing condition, as shown in Figure 10 (15% versus 6% for those with one pre-existing condition and 2% for those with two or more pre-existing conditions).

It is not known what proportion of the missing consultations is a direct result of a reduction in need because of the pandemic; for example, fewer treatments following car accidents or a reduction in the prevalence of non-COVID-19 communicable disease (especially among younger patients). The size of the reduction in consultations, however, suggests that there will be a high number of people with undiagnosed conditions coming into contact with the health system at a more advanced stage of their condition.

The relative reduction in consultations has been similar across ethnic groups, apart from those from a Chinese ethnic background who saw larger reductions and previously had a below average consultation rate.

By October 2020, primary care consultations had recovered to pre-pandemic levels and remained so until the end of January 2021.

Figure 10: Percentage change in consultation rate in 2020 compared with 2019, by number of pre-existing conditions and age, England, 2020

Source: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), Aurum database, Analysis from CPRD protocol number 20 143.

Note: Data for under 11 year olds with two or more pre-existing conditions are not available.

Referrals

At the beginning of the pandemic there was a substantial drop in 2-week wait for suspected cancer and urgent referrals. By autumn 2020, the rates of 2-week wait referrals and urgent referrals were broadly the same as in previous years. However, 2-week wait referrals did not increase enough to account for the substantial reduction during the first lockdown. Around 250,000 estimated 2-week wait referrals were ‘missing’ by the end of January 2021.

Routine referrals dropped by 74% during the first lockdown. This had not recovered by end of January 2021.

A&E visits

A&E visits began to fall 2 weeks before lockdown in March 2020 in England, falling to 48% compared with the same week in 2019 by the end of March. This recovered slightly to reach 64% of 2019 levels by mid-May. The fall in visits was greater for injury (54%) than for illness (32%). This is likely due to a combination of changes in NHS operations, in patient behaviour and in prevalence of conditions.

Those from the most deprived areas had 23.3% fewer emergency admissions in March to December 2020, compared with a 20.2% reduction for those in the least deprived areas. The IFS reported that the absolute gap in activity between local areas is substantially larger, since more deprived areas generally have more emergency admissions.

“Only 27% of people with long-term health conditions who needed NHS treatment in April 2020 received it, because of NHS cancellations.”

Elective care

During 2020, treatment activity fell in some specialties more than others. The largest impact was in trauma and orthopaedics, oral surgery and ear, nose and throat (ENT), with respective falls of 38%, 37% and 37% compared with 2019. In England, there were regional differences, with the largest fall in the north west (31%) and the smallest reduction in the south west (24%). The fall was greater in the most deprived areas (9,162 per 100,000 compared with 6,765 per 100,000 in the least deprived areas).

Survey data show that only 27% of people with long-term health conditions (such as cancer or cardiovascular disease) who needed NHS treatment in April 2020 received because of NHS cancellations. For other health conditions during this period, the NHS cancelled such treatment for more than two-thirds of people and around 5% of people cancelled treatment themselves.

There was a 29% decline in the number of patients referred to consultant-led elective care. In other words, there were 6 million ‘missing patients’ who did not seek treatment in 2020. If 75% of these ‘missing patients’ are referred for treatment as social distancing measures ease further, the waiting list for elective treatment could increase to 9.7 million by March 2024. By August 2020, almost three times more people had waited for more than 18 weeks as compared with August 2019.

Cancer

The number of patients seen for suspected cancer by a specialist dropped by 60% in April 2020 compared with 2019. Similarly, 37% fewer patients started treatment for cancer in May 2020. These numbers improved over the summer, narrowing to 8% and 10% respectively by October 2020.

Endoscopy activity from 23 March to 31 May 2020 was 12% of that between 6 January and 15 March 2020, which resulted in only 58% of the expected cancer cases being detected. From April to October 2020, over 3,500 fewer people had been diagnosed and treated for colorectal cancer in England than would have been expected. Survival from colorectal cancer is closely linked to the stage of disease, with over 90% of those diagnosed at stage I surviving 5 years compared with only 10% at stage IV.

Self-management of existing conditions

The fall in NHS treatments has adversely affected the health and wellbeing of people with existing conditions, as restrictions made their conditions harder to manage. For example:

- Diabetes (affected 3.9 million people in UK in 2019) – some adults with diabetes reported that their confidence to self-manage their condition fell during the summer (between 24 April and 31 August 2020), particularly their mental wellbeing (37%), as well as their physical activity (32%), eating patterns (29.6%) and ability to maintain a healthy weight (27.1%).

- Eating disorders (affected 700,000 people in UK in 2019, 90% of whom are women) – between June and July 2020, 83.1% of adults with an eating disorder reported a worsening of symptoms.

- Epilepsy (affected 600,000 people in the UK in 2010) – in June 2020, one in three young people with epilepsy reported that their seizures had increased during the pandemic and the majority reported that their sleep, mood and levels of physical activity had deteriorated.

Shielding population

Due to particularly high case numbers, the UK government advised 2.2 million of the most clinically vulnerable people to shield. Early data from NHS Digital shows that by mid-April, the drop in emergency admissions for shielding patients in England was greater than that for the general population (46% versus 33%). By July 2020, more than one in three of the shielding population had reduced access to care. Outpatient attendance for this group had fallen by 43% and elective admissions by 51%.

Perinatal and antenatal care

Women saw disruptions to perinatal and antenatal care. Scans became less frequent at the beginning of the pandemic and women reported difficulties discussing sensitive issues virtually and fears of further burdening the health system. Initial restrictions meant many women gave birth without a birthing partner and even once this changed there were still limitations on how long they could stay to support mothers. In Northern Ireland travel restrictions meant that women could not travel to England to access abortions.

Access to social care services

The pandemic has had a profound impact on social care services in England. Against a backdrop of pre-existing problems, such as chronic underfunding, workforce issues and system fragmentation, COVID-19 has made some of these challenges worse.

Analysis by the Health Foundation has found that despite an increase in care needs during the pandemic, fewer people have accessed local authority-funded long-term care than before the pandemic. In September 2020, 800 fewer younger adults and 12,150 fewer older people were supported in residential and nursing care than in March, a decrease of 2.6% and 10.5% respectively. This unmet need for care is occurring at the same time as an increase in unpaid care.

The COVID-19 impacts on care home residents and staff in terms of mortality, infection risk and access to PPE are covered in Section 5.

Mental health impacts of the pandemic

The mental health impacts of the pandemic have been mixed. For many, initial declines in mental health during periods of lockdown subsequently improved. A significant cohort have experienced a reduction in mental health, posing a potential longer term risk to the nation’s health.

Analysis from the ONS showed that around 21% of adults experienced some form of depression in early 2021 (27 January to 7 March), more than double that observed before the COVID-19 pandemic (10%). By March 2021, anxiety and depression had returned to levels seen during the lockdown easing in summer 2020.

However, one-fifth of the population experienced a sustained period of poor mental health relative to their previous levels by September 2020. By January 2021 around a quarter of working age people had experienced a new mental health problem during the pandemic. Diagnoses of self-harm, depression and anxiety and first anti-depressant prescribing decreased substantially in April across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. In England, the rates returned to expected levels in September but remained about a third lower than expected in the other nations. The evidence suggests that access to mental health care declined with implications for individuals, health care services and for society as a whole.

Who has been disproportionately affected by worsening mental health?

Analysis of two longitudinal studies (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children and the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study) found that in April–May 2020 those with financial problems, lower educational attainment, lower incomes or living in a more deprived area had disproportionately high rates of anxiety and depression.

The ONS also found that during 27 January–7 March 2021 a higher proportion of adults renting their home experienced some form of depression (31%) compared with adults who own their home outright (13%). Almost 3 in 10 (28%) adults living in the most deprived areas of England experienced depressive symptoms, compared with just under 2 in 10 (17%) living in the least deprived.

The pandemic is compounding mental health and economic hardship. Those experiencing income loss, loss of pay or with minimal safety net have been more likely to report poorer mental health. In January 2021, 43% of unemployed people had poor mental health. This was greater than for people in employment (27%) and for people on furlough (34%). This suggests that furloughing has provided some protection for people’s mental health.

Self-reported declines in mental wellbeing were twice as high for women as men. This is likely due to differences in caring responsibilities, social engagement and health behaviours. Women were more likely to spend longer doing housework and home schooling, alongside facing fears of redundancy and greater feelings of loneliness., When home schooling returned in January 2021 there was a significant increase in psychological distress among mothers, higher than in earlier waves, and compared with younger people during this period.

“Young people and disabled people experienced worse mental health outcomes compared with the general population.”

Young people and disabled people experienced worse mental health outcomes compared with the general population. The outcomes for these groups are explored further in Section 5.

Domestic abuse and child protection

For some people, having to stay at home increased the risk of experiencing domestic violence and abuse.

Analysis of domestic abuse cases held by the Metropolitan Police between 23 March 2020 and 14 June 2020 shows that abuse by current partners and family members had increased by 8.5% and 16.4% respectively, while abuse by ex-partners had declined by 9.4%.

Survivors reported escalating abuse during the first lockdown. Almost two-thirds (61.3%) of respondents to one survey said the abuse they were experiencing had worsened during lockdown; 54.8% said they had felt more afraid since the start of lockdown and 71.7% reported that their abuser had more control over their life.

Calls for help have remained high during both waves. Refuge reported an average 60% increase in monthly calls to their helpline between April 2020 and February 2021 compared with the start of 2020. 72% of these calls were from women directly experiencing domestic abuse.

Similarly, orders to stay at home have increased the risk to children experiencing violence and abuse at home. The NSPCC recorded a 53% increase in monthly average calls to their helpline between April and December 2020. The number of calls peaked in November 2020.

Research also suggests that school closures have resulted in fewer safeguarding referrals, indicating that children and young people had reduced opportunities to ask for help and no safe places where they could disclose. One study found a 37% decrease in referrals for child protection medical examinations between February and June 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.

Health risk behaviours

On average, health risk behaviours such as smoking and drinking alcohol decreased during the first lockdown. The percentage of adults smoking reduced from 14% pre-pandemic (in 2018/19) to 11% in April 2020. This reduction persisted and was still 11% in January 2021.

The same was true for drinking, with a slight decrease in the average number of units consumed per week – from 14.9 to 13.4 between March and June 2020.

However, this average reduction in smoking and alcohol consumption masks an increase in these behaviours among heavy smokers and drinkers. Lighter smokers were more likely to quit during the first wave, but in people who smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day there was no change.

By September 2020, 8.5 million people’s drinking levels were considered high risk, compared with 4.8 million in February 2020. There was also a 20% increase in alcohol-specific deaths in 2020 compared with 2019, the increase occurring between April and December, with deaths 28% higher in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared with a year earlier.

Analysis by Sport England, for ages 16 and older, found that physical activity levels declined during the early stages of the pandemic where there were just over 3 million fewer active adults (doing 150+ minutes a week of physical activity). As restrictions eased these declines in physical activity improved but did not recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Changes in the wider determinants of health

Summary

Relationships between friends, families and communities changed with stay at home restrictions in place. Many people reported feeling closer to family and their local community, but less connected to friends and other relatives. Loneliness increased over the pandemic. Those living alone, those with poorer underlying health or in rented accommodation were more likely to report higher levels of loneliness.

The closure of schools and reduced access to early years settings led to lost learning and development. Children from more disadvantaged backgrounds experienced higher levels of learning loss than their peers. A lack of social participation affected young people’s mental health and wellbeing.

The UK government launched unprecedented support to mitigate impacts on income and employment, including the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and the £20 uplift to Universal Credit. Despite these measures, people in shutdown sectors, those from deprived backgrounds, young people and the self-employed remained among those worst affected by the economic shock.

Challenges in housing security and homelessness were initially met with positive government measures. This included the introduction of mortgage holidays, the halting of evictions and schemes to house homeless people. Yet many families still struggled with housing payments, with an extra 450,000 families in rental arrears by January 2021 and 400,000 at risk of eviction in May 2021.

The greatest influences on health are the factors that shape the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age. Quality of work, housing, education, communities and family all impact on people’s health. The pandemic and the measures taken in response have had direct effects on these wider determinants of health.

Despite concerted and unprecedented measures to protect lives and livelihoods, there are short and long-term implications for the health of the population due to the effect of restrictions on families, communities, the economy, education and housing.

Friends, family and community

Positive relationships and feelings of connectedness contribute to good health and wellbeing. This was inevitably affected by the pandemic, with the scale of the response leading to radical changes in our day-to-day lives. Restrictions during the first wave limited people’s social contact with others outside of their own households and 51% felt less connected to friends and colleagues. In contrast, 47% reported feeling more connected to family and 45% more connected to neighbours.

“47% of people reported feeling more connected to family and 45% more connected to neighbours [during the first wave].”

Loneliness increased in Great Britain between spring 2020 and February 2021. Data from the ONS show that working-age adults living alone were more likely to report loneliness. Those in ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ health, those in rented accommodation, or who were either single, divorced or separated also reported higher levels of loneliness.

During the first wave, many local communities came together to support each other. By May 2020, there were 2,000 new local support groups on the Mutual Aid website and more than 5,000 neighbourhood-based Mutual Aid groups established to provide support for residents of local communities., More than 750,000 NHS volunteers signed up to help support vulnerable people.

This increase in community spirit was not experienced universally. People with lower levels of education and members of certain ethnic minority communities experienced a greater decline in perceptions of neighbourhood cohesion than their less disadvantaged counterparts. For some vulnerable groups, including people living in poverty or with pre-existing mental and physical health conditions, social support was persistently lower – by about 10–15% – than for those from wealthier backgrounds, or without physical or mental health conditions.

For the majority, feelings of neighbourhood cohesion were mirrored at the beginning of the pandemic by an increased sense of national unity. However, this does not seem to have been sustained. In April 2020, 57% of people thought that Britain would be more united than before once recovered from the pandemic, but by June 2020 this figure had fallen to 28%.

Unpaid carers

Greater responsibility for unpaid care has previously been linked to poorer mental health and greater risk of some physical health conditions., , ,

The number of people caring for older, disabled or seriously ill relatives and friends almost doubled during the pandemic from 17% of the population in 2018–20 to 32% in January 2021. By October 2020, unpaid carers were reporting increases in caring activity but reduced access to support. Many reported lower wellbeing, financial difficulties such as greater reliance on foodbanks, and lack of respite opportunities., , , ,

Carers are more likely to have poor health with over 60% of people providing over 20 hours of care a week having two or more long-term conditions. During the pandemic, over 20% have been waiting for NHS treatment.

Early years

Early years services have profound and lifelong effects on many aspects of health and wellbeing because they support social and emotional development and contribute to school readiness. Early years settings are particularly important for more disadvantaged children, helping to prevent gaps opening up in development levels at this early stage.

Before the pandemic, 68% of parents with children aged 2–4 years reported accessing formal early education or childcare. During the first lockdown this dropped to just 7% and by June 2020 the figure was still below 20%.

During the second wave, families were accessing early years settings more often but not at pre-pandemic levels. In February 2021, early years providers in England and Wales reported that attendance was still 28% lower than in the previous year. In England almost half reported lower take up of government-funded childcare entitlements.

Ofsted found that over half of early years providers felt that children’s personal, social and emotional development had fallen behind during the first lockdown. Almost half (45%) of parents reported a negative impact on their child’s social and emotional development, and 20% felt their child’s language and physical development was negatively affected.

Education

Government restrictions and lockdowns led to school closures, with most children and young people spending almost 60% less time in school by Easter 2021, with corresponding impacts on participation in learning and increased learning loss.,

There was some recovery in the autumn term when schools reopened and increased online provision in January 2021. But by the end of the 2020/21 spring term, primary school children had lost between 2 and 2.3 months of reading progress and between 3.1 and 3.6 months of progress in maths. Secondary school pupils also experienced similar levels of learning loss for reading, amounting to 1.6 and 2 months respectively for years 8 and 9.

The disruption of the pandemic has been greater for some children than others. School-aged children who are eligible for free school meals, have lower-educated parents or are in single-parent families spent less time on home learning than peers. In secondary education, schools with high rates of eligibility for free school meals had higher levels of learning loss than schools with lower rates (2.2 months versus 1.5 months) by autumn 2020.

Box 3: Digital exclusion

The pandemic transformed many day-to-day activities by accelerating people’s reliance on technology. Social distancing policies meant people having to use the internet to access vital services, such as financial, housing, health and social services. Internet access has been necessary to maintain connections with friends and family, to learn and work remotely, and to pursue exercise, faith, cultural and social activities.

This inadvertent and rapid shift in infrastructure widened inequalities for people digitally excluded: those lacking access, skills or confidence to use the internet. Before the pandemic, around 10% of the population had not used the internet in the previous 3 months or more. A considerable proportion of the UK population – 9 million people – is unable to use the internet independently.

Around 53% of the ‘offline population’ may lack the disposable income to afford an average monthly broadband bill of £30–35. The Good Things Foundation reports that certain groups – disabled people, older people, people on low incomes and those living in rural areas – are disproportionately likely to experience digital exclusion. These groups are also likely to have faced worse socioeconomic outcomes, showing how digital exclusion widens existing inequalities.

For example, digital exclusion has affected education and employment. Around one in five children did not have access to a suitable device for home learning during the pandemic, and 3% of school children were unable to do any schoolwork due to digital exclusion.

At the same time, many people with limited digital skills have embraced the internet during the pandemic. The proportion of homes without internet reduced from 11% in March 2020 to 6% in March 2021, while 75% of 50–70 year olds reported making video calls more often. There has also been a threefold increase in the number of 70 year olds registering for an online bank account.

In July 29% of teachers in the ‘most-deprived schools’ (as measured by the highest quintile of children on free school meals) reported that their children were 5 months or more behind, compared with only 5% of teachers in the least. Children from ethnic minority communities were also particularly disadvantaged by school closures. These are explored further in Section 5. The OECD estimates that learning loss equivalent to one-third of a school year can subsequently reduce earned income in later life by 3%. At an aggregate level the current cohort of years 1–12 losing just one-third of a year in effective learning has been estimated to reduce a country’s GDP by an average of 1.5% over the remainder of the 21st century. The negative consequences for individual and societal standard of living would be expected in turn to have negative consequences for health, particularly for those from more disadvantaged backgrounds. This risks widening future health inequalities.

Income and employment

Pandemic restrictions have had a profound effect on the economy, with the reduction in GDP in 2020 the greatest since current records began in the 1950s. Shutting down large parts of the economy has also reduced paid employment and as a result household incomes.,

The huge scale of financial support provided by government has helped to mitigate much of the impact of the pandemic on household finances, as have reduced outgoings for many families. This has left average income levels in 2020 similar to those in 2019. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme also has helped to prevent a large rise in unemployment and protected incomes by replacing a proportion of lost earnings. However, there is significant variation in how incomes and employment have been affected.

The duration of the economic shock has meant that by January 2021, 10% of the working population had been unemployed or on full furlough for 6 months or longer. The loss of status and routine that can arise from loss of employment, and reduction in income or disruption such as needing to move home, can increase stress and anxiety and cause depression. A sustained period without work can also cause a scarring effect on future employment chances and earning potential with longer term consequences on health. Increased debts to cover short-term income losses can also create future financial strain.

Box 4: Key government economic support through the pandemic

Job retention: From 1 March 2020 to 30 June 2021, the UK government paid 80% of employee wages, up to a cap of £2,500 a month, for businesses unable to operate fully due to COVID-19. From 1 July 2021 to 30 September 2021, this contribution is being reduced, with the scheme due to end in October 2021.

Self-employment income support: The government offered grants for self-employed people whose businesses were adversely affected. Eligibility required certain criteria: being a sole trader or a partner in a partnership, having been self-employed in the 2019/20 tax year, intending to continue trading in the 2020/21 tax year and being adversely affected by COVID-19.