Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a number of people who have helped with this research and the production of this report. These include a range of experts in scaling and spread whom we had the benefit of consulting: David Albury, Suzie Bailey, Amanda Begley, Dan Berelowitz, Helen Bevan, Anna Burhouse, Alison Cracknell, Helen Crisp, David Fillingham, Aidan Fowler, Michael Hallsworth, Abigail Harrison, Axel Heitmueller, Anne Kilgallen, Tom Ling, Annie Laverty, Alison Lovatt, Michael McCooe, Ross Millar, Greg Nathan, Rozenn Perrigot, Julie Reed, Mike Richards, Brian Robson, Beverley Slater, Charles Tallack, Anna Watson, Mary Wells, Tom Woodcock, and particularly Mary Dixon-Woods, whose research over many years has done so much to develop our understanding of this field.

We would also like to extend special thanks to all of the Health Foundation grant holders and project teams we worked with during the course of this research, including Steve Ariss, Tania Barnes, Nick Blake, James Breakwell, Bridget Callaghan, Mercy Darty, Jessica Deighton, Paul Dodd, Tom Downes, Tim Draycott, Alastair Ferraro, James Findlay, Bev Fitzsimons, Hugh Gallagher, Colin Gelder, Andy Henwood, Michael Holland, Jocelyn Hopkins, Peter Lachman, Sonia Lee, Claire Morrissey, Michael Nation, Clare Peckham, Lesley Peers, Mike Reed, Alan Taylor, Helen Ward and Martin Wilkie.

Finally, we wish to thank our colleagues Jennifer Dixon, Tim Gardner, Sarah Henderson, Bryan Jones, Penny Pereira and Tracy Webb for their helpful comments and insights in producing this report. Particular thanks to Oli Smithson, Insight & Analysis Support Officer at the Health Foundation, for his assistance in conducting the survey and preparing the manuscript.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone.

Key terms used in this report

Intervention: An intended change to existing practices or services that aims to improve health care. An intervention may consist of a single component or several different components that each contribute towards the intervention’s aims.

Innovator: The individual, team or organisation that developed the idea for the intervention or that first implemented it within the UK.

Spread programme: An initiative aiming to achieve the replication of the intervention in new sites or settings.

Programme leader: The individual, team or organisation leading the spread of the intervention to new sites or settings. (Where the innovator is leading the spread of an intervention they have developed, they will also be the programme leader.)

Adopter: An individual, team or organisation other than the innovator that implements the intervention in a different site or setting to the one in which it was originally developed.

Adaptation: A change made by an adopter to the intervention, compared to the innovator’s original version, as they implement the intervention in a new site or setting.

Codification: A description of the intervention, along with any supporting materials, aimed at enabling others to reproduce it. Codifying an intervention requires thinking through what adopters will need to know in order to reproduce it successfully, for example, what is core to making the intervention work and what can be adapted.

Innovation and improvement: New approaches, practices, treatments, technologies and services that aim to improve health care. The analysis in this report applies to both innovation and improvement; on some occasions we use both terms together, and on others we use one as a shorthand for both. (As described above, we use the term ‘innovator’ to refer to the individual, team or organisation that developed the idea for the intervention, whether it is an ‘innovation’ or an ‘improvement’.) Improvement, including formal quality improvement (QI) using a structured method, is often used to describe incremental change within an existing service model, whereas innovation can be used to mean disruptive change that creates a new service model. Furthermore, innovation is often viewed as a discrete, one-off change, whereas improvement is often viewed as iterative and ongoing. Nevertheless, both innovation and improvement tend to involve one or more interventions (see above) and it is such interventions that are the main focus of our analysis here.

Scaling and spread: Activity that results in an intervention being replicated across multiple sites. Scaling, which is a subset of spread, refers to an initiative to replicate an intervention specifically through a higher-level organisation or geographical entity (such as a professional body or government agency); but spread can also happen through horizontal connections between adopters, without the involvement of a higher-level entity. The analysis in this report applies to both scaling and spread; we sometimes use both terms together, though more commonly ‘spread’ is used as a shorthand for both.

Executive summary

What this report is about and why it matters

How to spread new ideas and effective practices from one organisation to another to improve care and reduce unwarranted variations in performance is one of the central challenges facing the NHS.

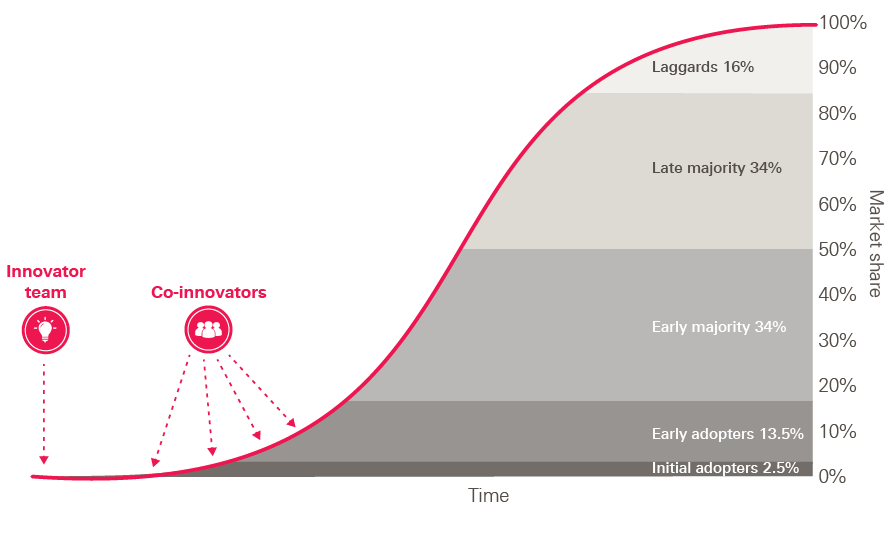

For decades, centuries even, people have debated the problem of the slow spread of innovations in health care. A classic example is the incorporation of citrus fruit into sailors’ diets to prevent scurvy – demonstrated by James Lancaster in 1601 and again by James Lind in 1747, but not adopted by the British navy until 1795. And since Everett Rogers published his classic work The Diffusion of Innovations in 1962, much debate and scholarship on innovation has focused on the factors that affect whether people take up innovations or not and how quickly they do so.

This report focuses on a different problem, one that has received far less attention, but which we believe is equally pressing: that when an individual, team or organisation does take up a new innovation it may not work as well as it did first time round – something we see particularly with complex health care interventions that seek to make improvements in clinical processes or pathways. We therefore set out to investigate not the factors affecting the uptake of innovations in health care, but the factors affecting their successful uptake. We do this in several ways, reviewing the literature on this problem, drawing out lessons from Health Foundation projects and evaluations, and also interviewing key actors – innovators and adopters, who provide vital insights from the front line of health care, as well as expert stakeholders involved in supporting scaling and spread.

Indeed, this ‘replicability problem’ – the challenge of replicating the impact of a new intervention as well as its external form – is arguably the more urgent question for the public sector, and for the NHS in particular, where all manner of mechanisms exist to encourage uptake, and indeed to mandate it in the last resort. But the last 70 years of NHS history have shown that mandating action does not automatically bring about the desired change in outcomes.

Achieving that is much harder. It requires teams on the ground to adapt and implement a new intervention in ways that will enable it to work in their own setting. Staff may need to develop new skills or learn to use new techniques. There may be a need for culture change, relationship building, new ways of working or undoing entrenched habits – none of which can be achieved purely through compulsion.

Framed in this way, it is clear that while the invention of new technologies, practices and models of care are exciting moments in health care, invention itself is only half the story. People sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that when an idea has been successfully demonstrated or piloted then the hard work is done. But exploiting the full potential of a new idea requires successful replication at scale – and this takes time, skill, resources and imagination.

So as policymakers and system leaders draw up the anticipated long-term plan for the NHS in England, it is important that debate is not restricted simply to identifying areas for improvement and potential solutions. The challenge is to get the solutions working well everywhere.

This report discusses some of the changes in thinking and approach needed to tackle this challenge, drawing on lessons from the Health Foundation’s programmes to support the spread of innovation and improvement in health care.

One part of the answer is changing the way we think about what is actually being spread. In the case of a discrete health care intervention, does our conceptualisation of the intervention encompass the full range of factors necessary for its success, such as underlying behaviours or cultural factors, the skills and capabilities required, the methodology for implementation, and so on? This applies not just to process innovations, quality improvement approaches or new service models, but also to interventions using new health technologies or medical devices – where there is often a tendency to focus on the technology itself, even though its effectiveness will depend on the skills, behaviours and organisational cultures of those using it.

Another part of the answer involves designing programmes that will better support the spread of new interventions. Do these programmes generate consensus on the new idea and buy-in from those adopting it? Do they provide for sufficient support during implementation to enable the idea to be successfully reproduced? Factors such as these could have major implications for the success of programmes to scale up new ideas or reduce variation in the NHS.

We hope the analysis and insights in the report will be relevant both for innovators and adopters, and also for those designing and leading spread programmes. The latter includes those overseeing local programmes, whether they are run by commissioners, academic health science networks (AHSNs), regional and national improvement bodies or professional networks. It also includes policymakers and system leaders overseeing national change programmes, such as Getting It Right First Time or RightCare, and national bodies whose remit includes spreading innovation and improvement, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, royal colleges and professional bodies.

The central argument of the report

Our central argument is that successfully spreading complex health care interventions will require packaging them up in more sophisticated ways and designing programmes to spread them in more sophisticated ways.

The point of departure for the report’s analysis is to note that the success of a complex intervention is likely to depend heavily on its context: the underlying systems, culture and circumstances of the environment in which it is implemented. This means that adopting a complex intervention and making it work in a new setting is not a straightforward matter; in fact, as many of the Health Foundation’s grant holders tell us, it can be extremely hard work. Successful implementation may require adaptation of the intervention or a long journey to build new relationships, shift the prevailing team culture or develop new skills.

Recognising the influence of context highlights the important role adopters play in translating interventions to new settings. This poses a challenge for traditional approaches to spreading innovation, which tend to assume that once an innovator has developed an idea and successfully piloted it, it can then be ‘diffused’ and taken up by others in a straightforward way. By contrast, we argue that reproducing a complex intervention at scale is a much more distributed effort, often involving a good deal of creativity and reinvention from those taking it up, with the intervention itself sometimes undergoing substantial revision and refinement in the process.

We argue that designing spread programmes that can meet the challenges of adoption will therefore place a greater focus on adopters, to some extent reversing the conventional focus on the innovator. This requires ‘codifying’ interventions in ways that support adopters to adapt them appropriately. It requires designing programmes in ways that build adopters’ commitment to implementing the intervention. It requires mechanisms such as peer networks to capture and share the learning that adopters generate as they tackle implementation challenges. Above all, a greater focus on adopters requires building their capability and readiness for implementation and providing them with the resources, time and space needed to do the hard work of translating the original idea to their own setting.

Chapter summary

Chapter 1 gives a brief overview of the ‘replicability problem’.

Key points:

- When initially successful interventions are spread to new settings, they may fail to achieve the same impact, or indeed any impact at all.

- One explanation for this may be that interventions are not being conceptualised and described in ways that enable them to be successfully reproduced in new contexts, and programmes to spread interventions are not being organised in ways that adequately support adopters to reproduce them.

- These challenges become especially acute with complex health care interventions, such as innovations and improvements in clinical processes and pathways.

Chapter 2 looks at why the complexity of many health care interventions poses challenges for spreading them.

Key points:

- Complex interventions tend to have certain properties that make codifying and replicating them difficult: they are social, context-sensitive and dynamic in nature.

- Various approaches and schools of thought exist for analysing complexity, such as realist evaluation or complex adaptive systems theory, but they all represent routes for capturing and responding to these properties of complex interventions.

- Insufficient appreciation of complexity can lead to mistakes and misconceptions in attempts to codify and spread interventions. These can include failing to consider the social as well as technical components of the intervention, failing to distinguish between the instrumental and expressive effects of intervention components, or failing to recognise capability-building as an integral part of the intervention.

Chapter 3 considers some approaches to codifying complex health care interventions in ways that can support effective replication.

Key points:

- Some approaches to codification aim for ‘tight’ descriptions of the intervention through comprehensive and detailed accounts, for example, specifying the methods for implementation or the social mechanisms and behaviours required for success. Other approaches aim for ‘loose’ descriptions, focusing less on the details of each intervention component and more on the ability of adopters to formulate their own versions of these components in their own setting, for example, by setting out the underlying principles and goals, the intervention’s theory of change, or the skills and capabilities required. Furthermore, tightening and loosening approaches can sometimes be blended.

- Whichever approach is taken will have implications for the concept of fidelity to the intervention, as well as for the broader approach to spreading the intervention.

- Innovators and programme leaders should be aware of different possible approaches to conceptualising and describing interventions; they should be seen as a standard part of the innovator’s toolkit.

Chapter 4 looks at the initial spread process and at how early adopters generate new learning about an intervention as they implement it in new contexts.

Key points:

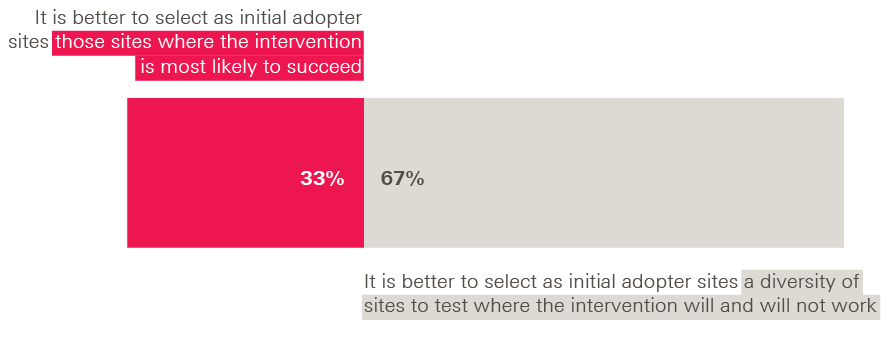

- As innovators cannot necessarily ‘see’ their own context, introducing a new intervention into a diverse range of sites can generate fresh insights into what is (and isn’t) significant for making it work. This allows the innovator to revise the description of the intervention accordingly, and in some cases to refine the intervention itself.

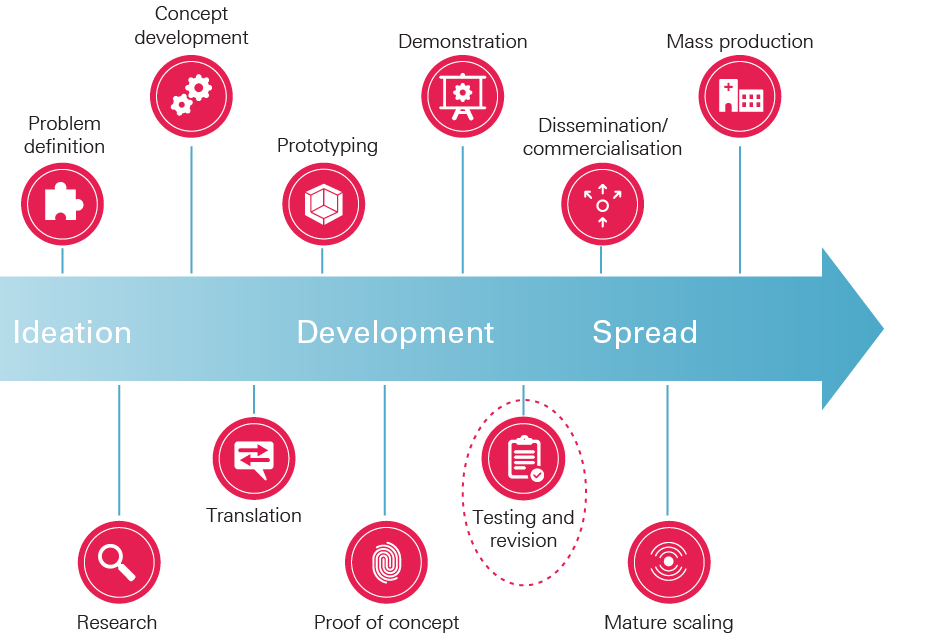

- There may be value in recognising this testing and revision phase as a formal part of the innovation cycle in health care, distinct from attempts to spread interventions at later stages of maturity.

- This has implications for the design of the initial spread process, in terms of setting expectations, selecting initial adopter sites to ensure diversity, fostering good relationships between the innovator and the initial adopters, and ensuring that mechanisms are in place to capture and share new learning.

Chapter 5 looks at some consequences for the design of large-scale spread programmes.

Key points:

- Spread programmes need to be designed in ways that build and maintain adopters’ commitment to implementation, including seeking consensus on both the problem and the proposed solution.

- These phenomena have important psychological, behavioural and social dimensions that should be considered when designing spread programmes. Important areas where behavioural insights can inform the design of programmes include peer leadership, peer communities and adopter ownership.

- Successful spread also relies on adopters’ ability to implement the intervention and on them having sufficient opportunity to do so. This implies that spread programmes need to build adopter readiness and capability (for example, through providing training or enabling relationship building), include appropriate support for implementation (for example, funding to cover the upfront costs of adoption, or assistance with analytics and evaluation), and be based on realistic timescales.

The conclusion draws out the implications for policymakers and those overseeing spread programmes.

Key points:

- Adopters make a crucial contribution to the successful spread of new ideas, both through the hard work involved in adoption and their role in generating new learning about an intervention as it spreads.

- This perspective challenges conventional notions of the division of labour between innovator and adopter. It also challenges the ‘knowledge pipeline’ model of innovation, which sees new knowledge as generated purely by the innovator and which casts adopters as passive recipients of this knowledge during the diffusion process.

- There needs to be greater emphasis on the role and status of adopters within spread programmes, both in terms of how interventions are codified and how programmes are designed. Beyond specific spread programmes, policymakers can ensure health care providers are better equipped for adoption more generally by supporting them to build their improvement capability.

The replicability problem

Although replicating successful health care interventions in new contexts is clearly essential for maximising the benefits of new ideas and innovations for patients, it is also a well-recognised challenge. A commonly seen phenomenon is that when initially successful interventions are spread to new settings they may fail to achieve the same impact, or indeed any impact at all.

The phenomenon of surgical safety checklists provides an example of these variable fortunes. While the introduction of such checklists around the world has sometimes been associated with significant reductions in surgical complications and mortality, in other cases it has not led to improvements, even when compliance with the checklist has been high.

On other occasions, even when some impact is achieved, there can be a reduction in effectiveness or ‘voltage drop’ as initiatives are replicated. In the field of social programmes more broadly, this phenomenon was nicknamed the ‘Iron Law’ by evaluator Peter Rossi in the 1980s, who argued that as a new initiative is implemented across more and more settings, the impact will tend toward zero.

There may sometimes be straightforward explanations for this ‘replicability problem’, such as a failure by adopters to adhere to the intervention protocols. In recent years, however, there has been growing interest in a deeper set of explanations: that we may not be describing interventions in ways that enable them to be successfully reproduced in new contexts, and that we may not be designing programmes to spread interventions in ways that adequately support adopters to reproduce them.

This problem of replicability is different from the one that has traditionally preoccupied innovation research, namely, identifying what drives the uptake of new ideas. Much of this wider research stems from Everett Rogers’ seminal work on the diffusion of innovations, first published in 1962, which explored the properties of innovations and social systems affecting uptake. A more recent and highly influential contribution is the review of the literature on the diffusion of innovations in service organisations by Trish Greenhalgh and colleagues, who highlight the roles played by a large range of factors in driving the adoption of innovation in health services. Here, by contrast, we are concerned not simply with uptake but with the challenge of successful or effective uptake and the factors that affect whether someone can replicate an intervention’s impact when they do take it up.

Perhaps it is not surprising that this proves such a challenge. For an adopter to be able to reproduce an intervention successfully, they need to understand how they can translate the idea into their own setting, they need to know just what matters for the intervention to work in this new setting, and they need to have the opportunity, motivation and capability to implement it. None of these things are trivial, yet it is surprising how often they are taken for granted in initiatives to scale up and spread new ideas.

This goes beyond the well-known phenomenon of incomplete descriptions of interventions, with crucial details often omitted from reports, hampering effective replication. For example, Hoffman and colleagues analysed reports from a large sample of randomised trials of non-drug interventions and found that more than half (61%) were not described in sufficient detail to enable replication of the intervention in practice. Rather, the issue may be whether we are conceptualising the interventions themselves in the right way. For example, is the conceptualisation broad enough to incorporate all those aspects of context that might impinge upon the intervention’s effectiveness? Or does it strike the right balance between the ‘what’ and the ‘how’?

And these challenges become especially acute with complex health care interventions, particularly innovations in clinical processes and pathways of the kind that the Health Foundation has supported over many years, such as improvements in patient flow or hospital discharge. This includes the use of new technologies such as apps and medical devices; these are sometimes viewed as ‘simple’ interventions, but their effectiveness will depend on the skills, behaviours and cultures of those using them, and the evolution of new ways of working to maximise their benefits.

This report presents lessons and insights on how to tackle these challenges that have emerged from Health Foundation programmes and research. It begins by considering why complexity poses problems for conceptualising and replicating interventions, before moving on to consider the implications both for how we describe interventions and how we support their spread.

The Health Foundation’s programmes to support scaling and spread

Over the last decade, the Health Foundation has run five major programmes to support the spread of innovations and improvements in health care. These have included programmes explicitly designed to support teams to spread complex interventions to new sites (such as the Scaling Up programme), as well as programmes seeking to improve health care at scale more generally (such as the Closing the Gap series of programmes) but which nevertheless included projects of the kind we are concerned with here (namely, those engaged in spreading defined interventions to specific sites).

Table 1 gives the details of these programmes dating from 2009 to 2017. Since then, a third round of the Scaling Up initiative has been launched, supporting a further seven teams.

Table 1: Details of Health Foundation programmes on scaling and spread 2009–2017

|

Programme |

When it ran |

Aim |

Investment (including evaluation) |

Number of projects supported |

|

Closing the Gap through Clinical Communities |

2009–2012 |

To support the uptake of improvement interventions through established clinical networks |

£5.3m |

11 |

|

Closing the Gap through Changing Relationships |

2010–2013 |

To support organisations to implement interventions that improve the relationship between people and health services |

£3.9m |

7 |

|

Closing the Gap in Patient Safety |

2014–2016 |

To scale evidence-based patient safety interventions through groups of collaborating organisations |

£4.0m |

9 |

|

Spreading Improvement |

2014–2017 |

To support teams to spread their improvement interventions through creating contexts and infrastructures that support diffusion |

£2.2m |

5 |

|

Scaling Up (Rounds 1 & 2) |

2014–2017 |

To support teams to implement tested improvement interventions at scale, in partnership with organisations that can support regional or national spread |

£7.4m |

13 |

With one team receiving a grant in more than one of these programmes, there are a total of 44 discrete projects across the five programmes, listed in Appendix 1.

How we have learned from the Health Foundation’s programmes

The insights presented in this report emerged from interviews with many Health Foundation grant holders and partners during 2017 and 2018.

We also benefited from close engagement with several of the projects supported by the Health Foundation’s programmes, through interviews with innovators, adopters and evaluators conducted in 2017 and 2018. Three of these projects are presented as detailed case studies in this report:

- Shared Haemodialysis Care, a project to spread an approach to haemodialysis that gives patients the opportunity to take a greater role in their own care, beginning in 12 dialysis units and subsequently spreading to a further seven units in England between 2016 and 2018, as part of the Health Foundation’s Scaling Up programme (see Chapter 3).

- Respiratory Innovation: Promoting Positive Life Experience (RIPPLE), a project to spread a new model of community clinic for tackling social isolation and improving health for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to six sites across the East and West Midlands between 2015 and 2018, as part of the Health Foundation’s Spreading Improvement programme (see Chapter 4).

- Situational Awareness For Everyone (SAFE), a project to implement patient safety huddles – initially in 12 paediatric units and subsequently in a further 16 units in England between 2014 and 2017 – as part of the Health Foundation’s Closing the Gap in Patient Safety programme (see Chapter 5).

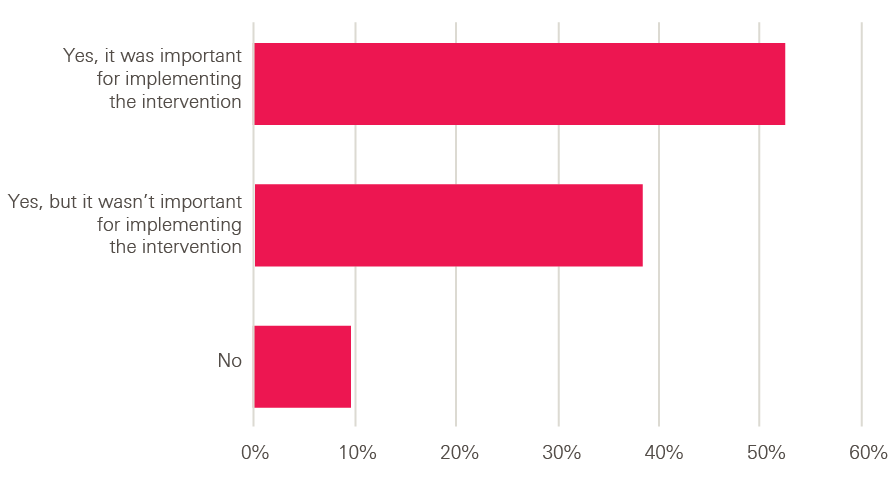

In addition, we conducted a survey of innovators and adopters from the Health Foundation’s spread-related programmes during December 2017 and January 2018, the results of which are presented at various points throughout this report. Further information on the survey is given in Box 1.

Finally, throughout the report, we draw on examples and evaluations from the Health Foundation’s improvement work more broadly, both from the spread-related programmes listed above and other relevant programmes such as Safer Clinical Systems (2008–2016) and Flow Cost Quality (2010–2012).

Box 1: Our survey of innovators and adopters from the Health Foundation’s programmes

Over the last decade, the Health Foundation has funded five major spread-related programmes, which together have supported 44 different projects. After analysing each of these projects, we concluded that 26 could be categorised as aiming to spread a defined intervention or approach to specific adopter sites – the paradigm of scaling and spread with which this report is concerned. The other 18 projects took different approaches to achieving improvements at scale, such as by influencing national guidelines or through improvement collaboratives supporting different interventions in different sites.

To investigate the views of programme participants, we conducted surveys of the innovators and, separately, the adopters from these 26 projects, throughout December 2017 and January 2018, using Qualtrics software. We received responses from 21 innovators and 42 adopters.

The survey asked them about their experiences of trying to spread or implement an intervention as part of the relevant Health Foundation programme; sought their reflections on the process with hindsight; and invited their views on general questions about spread and adoption within the context of their experiences in the Health Foundation programme. The results are illustrated at various points throughout this report.

The complexity of modern health care interventions

The previous chapter highlighted how reproducing the desired impact of a new health care intervention can be a particular challenge in the case of complex interventions. This chapter explores why complexity poses problems for spreading and replicating interventions.

There is no single definition of a complex health care intervention, though analyses of complexity tend to highlight certain features:

- the presence of multiple components, either independent or interacting

- context-embeddedness: complex interventions are built on and interact with the underlying systems, culture and circumstances of the environment in which they are implemented. Indeed, some interventions will be so embedded in their context that it can be hard to distinguish the intervention from its implementation in a specific context.

- intricacy of causal pathways (that is, the ways in which interventions achieve their effects): these pathways can be multiple and interacting, possibly containing feedback loops, with the effects of some intervention components reinforcing or moderating the effects of others.

Of course, these characteristics are not unrelated. A greater number of intervention components and potential interactions between them will tend to increase the number of ways in which the intervention might supervene upon and interact with the underlying organisational context. And all of this has the potential to increase the complexity of the causal pathways by which the intervention achieves its effects.

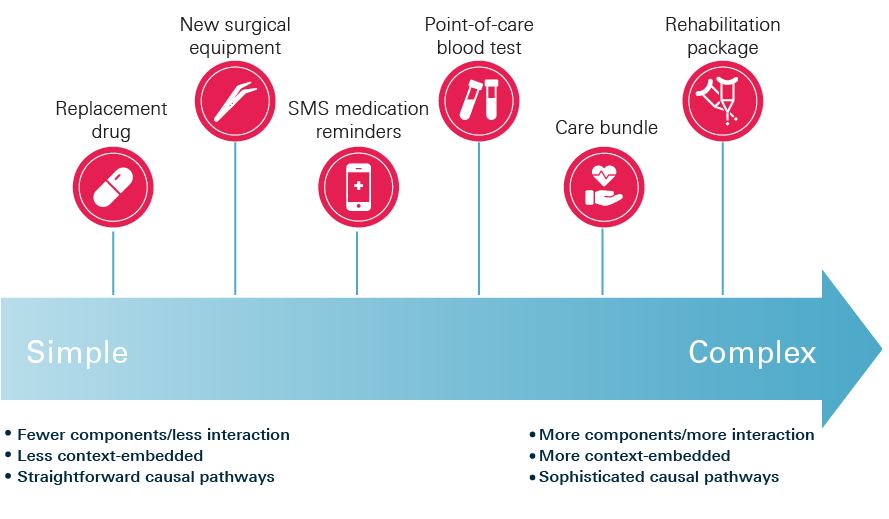

The indefinite and potentially contested nature of these characteristics does not always lend itself to drawing hard and fast distinctions about which interventions are complex and which are not. Rather, it might make more sense to think about degrees of complexity. For example, we can imagine a spectrum ranging from simple to highly complex. At one end might be an innovation like a pill, or an intervention that replaces one type of pill with a more effective one. At the other end could be an intervention like a rehabilitation programme, which has multiple components delivered in a range of settings and relies upon a significant degree of patient co-production and behaviour change. In between, one can imagine a range of intervention types that share these characteristics to varying degrees.

Figure 1: Intervention complexity spectrum

Note: Figure 1 illustrates some common types of health care interventions and where they might typically sit on this spectrum. However, we do not intend to suggest that all instances of a particular type of intervention will be of equal complexity.

A failure to consider the full range of issues involved in implementing an intervention could lead one to underestimate its degree of complexity, as illustrated in the case of the Sepsis Six care bundle, described in Box 2. And the more we underestimate the complexity of an intervention, the more likely we are to underestimate the challenges involved in replicating it in new contexts.

Specifically, complex interventions tend to have certain properties (related to the characteristics outlined above) that explain why codifying and replicating them can be so difficult.

First, complex interventions are social, in that they are co-produced and delivered by health care staff, patients and carers. This implicates the attitudes, behaviours, relationships and organisational cultures of those adopting an intervention in its success or failure. Understanding how particular intervention components work may therefore require understanding the social mechanisms that facilitate them, and successful replication may require adopters to re-create these social dynamics in their own setting.

Second, the fact that complex interventions are context-embedded means they are context-sensitive: an intervention’s success will be influenced by aspects of the organisational and wider context in which it is implemented, including the social and relational elements described above. This means it may be necessary for the intervention description to set out which aspects of context influence its effectiveness, and how, in order to aid replication. And to the extent that aspects of organisational context may differ from one location to the next, successful replication may require adaptation of the intervention. As a result, the same intervention may look different in different contexts; for example, when interventions are co-designed with patients, local patient priorities will shape the intervention (and, in the process, challenge standardisation). This, in turn, means that the intervention description will need to capture which components are ‘core’ to making the intervention work and their tolerance to alteration across different settings – what needs to remain invariant versus what can be changed and to what extent.

Third, complex interventions are dynamic, in that the ‘systems’ (people, teams, organisations, etc.) that implement them can learn and self-organise, and the contexts in which they are implemented can throw up new issues requiring a response from those involved., This means that a complex intervention may evolve over time and in unpredictable ways. What is more, its fate may rely heavily on the adopter’s ability to navigate these dynamics and adapt. Indeed, the degree of adaptation and responsiveness required will have consequences for the extent to which the success of the intervention is seen to reside in the specific intervention components themselves versus the agency and capability of the adopter.

Box 2: The complexity of apparently simple interventions: the Scottish national collaborative programme on sepsis

The varying success of an intervention across different contexts can sometimes be a symptom that its underlying complexity has gone unrecognised. One example is the ‘Sepsis Six’ clinical care bundle, which focuses on six key tasks required to treat a patient with sepsis within one hour of diagnosis, including prompt administration of antibiotics and oxygen. Studies have shown significant variation in the effectiveness with which sepsis care bundles are implemented. In light of this, an ethnographic study sought to understand the realities of implementing Sepsis Six on the front line through an investigation of the Scottish national collaborative programme on sepsis, which ran from 2012 to 2014.

Superficial consideration might suggest the Sepsis Six bundle comprises six steps. However, the researchers identified some 48 steps typically required for implementation of the six key tasks. Some required significant input from several staff, making completion within one hour challenging. For example, to effectively administer high flow oxygen, the staff member had to find a doctor and get oxygen prescribed, assess the patient for COPD, gather equipment, wash their hands, explain the reason for the procedure and gain patient consent, administer oxygen, check for comfort and document the procedure.

Across the six key tasks, there were interdependencies inherent in the sequencing of different steps and a lack of synchronisation could arise when staff had to resolve competing demands or manage interruptions. Some steps had social as well as technical dimensions, relying on collaboration between multiple groups of professionals; for instance, nurses in most cases were reliant on doctors to prescribe antibiotics, and on other nurses to check and sign, before they could administer the antibiotics.

The researchers concluded that the challenges of prompt and reliable implementation of the Sepsis Six bundle involve ‘the socio-technical complexity of completing interdependent tasks requiring multiple individuals in different professional groups in a frenetic environment characterised by competing priorities’, and that improving performance ‘requires attention to problems of coordinating tasks, workflow, accountability and expertise’. So, while packaging together different care processes into ‘bundles’ may well be helpful for ensuring consistency, it is clear that effective implementation requires grasping the complexity of the underlying processes and creating working environments that enable them to be delivered.

Analysing complexity

A range of theoretical and practical approaches have evolved for analysing complexity in both health care and health promotion.

One example is realist evaluation, which attempts to understand how an intervention’s outcomes were produced in terms of the underlying mechanisms that drive behaviour and the influence of context on how actors respond. Specifically, realist analysis considers which configurations of context, mechanism and outcome offer the most plausible explanation for the intervention’s effects (here, ‘mechanisms’ are not intervention components but underlying processes triggered by the context that causes or facilitates the intervention’s outcomes).

Realist evaluation is one of a broader set of theory-based approaches that seek to explain how interventions work by elucidating the intervention’s ‘programme theory’ or ‘theory of change’. All interventions are seen as underpinned by a theory – whether the practitioner is aware of it or not – but without making this explicit, it is difficult to fully understand the mechanisms that underpin the intervention’s effectiveness. By uncovering how an intervention works, theory-based approaches can lead to revisions in the innovator’s understanding of their intervention, sometimes in unexpected ways. Box 3 provides an example from the Health Foundation programme Closing the Gap in Patient Safety.

Another type of approach comes from complexity science and complex adaptive systems theory., These disciplines consider an intervention in terms of a system of interdependent agents whose interaction gives rise to emergent, system-wide patterns of behaviour that cannot be reduced solely to the impact of its component parts. Furthermore, such complex systems can self-organise, giving rise to unpredictability, and meaning interventions can evolve.

Different schools of thought handle issues of complexity in contrasting ways. Some view complexity primarily as a property of the intervention and seek to draw relevant background conditions and enabling factors into the conceptualisation of the intervention itself, whereas others tend towards seeing complexity as a feature of the context in which the intervention is embedded. Another point of contrast concerns how and at what level to capture causality: for some, the way to navigate the context dependency of complex interventions is to describe the function of different components within the intervention’s theory of change rather than their specific form; others question whether it is possible to capture causality in this way, because of the difficulty of linking individual components to outcomes, and seek instead to understand the system-level changes triggered by the intervention.,

Whether or not the divisions between the different schools of thought that exist are helpful is debatable. Nevertheless, while we do not seek to play down the philosophical differences between them, in our view they all represent routes for capturing the same underlying features of complex interventions highlighted here: an intervention’s social dimension, how it embeds in its context and how it may evolve over time as those implementing it learn and adapt.

Box 3: Understanding how interventions work: surviving sepsis in Northumbria

Scrutiny of the factors underpinning an intervention’s success can reveal that interventions sometimes have their effects in unexpected ways, requiring those codifying or implementing the intervention to revise their theory of change.

In 2013, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust had a higher than expected mortality rate for people admitted with sepsis, which led to sepsis being identified as a priority for improvement. Supported through the Health Foundation’s programme Closing the Gap in Patient Safety, in 2014 the trust began a quality improvement project to reliably screen patients for sepsis and, where sepsis was identified, to treat them using the Sepsis Six care bundle.

Within 15 months, the project resulted in an increase in patients receiving Sepsis Six within the first hour from fewer than 10% to approximately 60%. Analysis of results from 8,000 screened patients suggest that an estimated 158 lives were saved from reductions in mortality rates.

However, through the project evaluation, the team was surprised to discover that raising staff awareness of the possibility of sepsis through reliable screening ultimately made the greatest contribution to reducing mortality rates; patients assessed using the screening tool were shown to have a 21% lower mortality rate than those for whom the tool had not been used. The subsequent use of Sepsis Six following screening contributed to a further reduction in mortality rates, but not of the same magnitude.

The team also learned about the mechanisms by which the screening tool had this effect. As well as providing a clear pathway for the steps to be taken when sepsis was identified, the tool also promoted team coherence, not least by legitimising nurses’ role in escalating patients and initiating treatment. This was a significant change in practice, as previously nursing staff had simply reported deterioration and awaited instructions from the doctors.

Some common mistakes and misconceptions

The features of complexity considered here pose challenges not just for understanding how an intervention achieves its effects but also for trying to spread it to other settings. The challenges involved can be illustrated by considering some common mistakes and misconceptions that can occur in attempts to codify and replicate interventions.

The first is the belief that the technical components form the ‘hard’ core of an intervention, while the social components are ‘soft’ – that is, discretionary or more open to variation. In fact, the social components may be essential for the intervention to work. This was illustrated in a study of a successful programme to reduce central venous catheter bloodstream infections in intensive care units (ICUs) across Michigan. Some contemporary accounts had viewed the intervention as a simple checklist of five technical components, such as using chlorhexidine for skin preparation and barrier precautions during catheter insertion. However, the study found that the checklist also had an important social function in promoting adherence to these technical practices, because the programme did not simply ask ICUs to use the checklist, but also specified that every catheter insertion should be monitored by a nurse, who would immediately raise concerns if the protocol was not followed. Importantly, this requirement presupposed a restructuring of professional relationships, flattening the traditional hierarchy within the ICU, and it would only work if nurses were able and willing to intervene. In turn, the study found that unwavering support from senior consultants was crucial in enabling nurses to act in this way. Whether one regards such social and relational dynamics as aspects of ‘context’ or of the intervention itself, exposing and understanding them can be essential for effective replication. And this is true not just for interventions that may outwardly appear ‘social’, such as the creation of new teams or ways of working, but also for the use of new technologies or devices; in such cases, the benefits rarely come purely from the technology itself, but rather from the technology being successfully embedded in the human environment of a care process or pathway.

A second possible misconception is to confuse the direct or instrumental effects of intervention components with their expressive or symbolic effects. For example, the study of the Michigan programme cited above found that the requirement for ICUs to create a dedicated trolley containing all the items required for successful catheter insertion not only had instrumental benefits in averting delays but also expressive ones: it signalled the organisation’s commitment to infection control and heightened awareness of the programme. Another example, from the Health Foundation’s Safer Clinical Systems programme, comes from a project which aimed to reduce medication errors on a hospital ward. One component activity, nicknamed the ‘dabber audit’, involved dabbing medication charts with different coloured ink stampers to indicate whether they were correct or needed further action. Originally intended to simplify the data collection process, its visibility meant it came to be regarded as a powerful motivator of behaviour and an educational tool – and as its function mutated, it became possible to see the dabber audit as an intervention in its own right. Sensitivity to the expressive as well as the instrumental functions of an intervention component in a particular context can be important for describing it in a way that supports others to replicate the same effects.

A third possible misconception is a failure to recognise capability-building as an integral part of the intervention. Again, the perception of checklists as a catch-all provides an illustration. While the introduction of surgical safety checklists around the world has sometimes been associated with reductions in surgical complications and mortality, when their use was mandated in Ottawa in 2010, an evaluation found no such improvements, even though compliance with the checklist was high. The researchers noted that, unlike other instances where positive effects of using surgical safety checklists had been observed, the introduction of the checklist in Ottawa had not included team training on how to use it. They suggest a greater effect might have occurred had training been provided.

***

These social, context-sensitive and dynamic properties of complex interventions mean that substantial effort and creativity may be required by adopters to translate a new intervention into their own setting and make it work successfully. The next three chapters explore three specific challenges this creates for spread programmes:

- how to codify complex interventions in a way that can support their implementation in new contexts (Chapter 3)

- how to incorporate learning from attempts to implement the intervention in new contexts in order to revise and refine it (Chapter 4)

- how to design spread programmes in ways that build adopters’ commitment and support their work in translating the intervention into their own context (Chapter 5).

Codifying complex health care interventions

The previous chapter looked at how complexity poses challenges for codifying health care interventions in ways that can support effective replication. This chapter considers some possible approaches to codification in response.

Adequate description of an intervention’s technical components is, of course, often critical for effective replication. Research studies highlight the role that poor quality descriptions of technical components can play in preventing successful spread. This has led to the development of approaches to assist innovators and evaluators in producing more robust intervention descriptions – for example, the TIDieR framework.

However, the analysis in the previous chapter suggests that successfully replicating complex interventions also requires codifying them in ways that go beyond a description of the technical components and allow adopters to navigate the underlying social, contextual and dynamic forces.

Various approaches to codification are evident in the evaluation and implementation science literature, as well as in practice in the Health Foundation’s programmes. These are characterised by two contrasting impulses we would describe as ‘tightening’ and ‘loosening’.

Some approaches seek to ‘tighten’ the intervention description in response to the challenges of codification by attempting more comprehensive or fine-grained specifications than simply a straightforward description of the intervention’s technical components. This could include specifying the method for implementing particular components, for example, ‘lean’ principles. Another possible tightening approach is to set out relevant social mechanisms and dynamics in addition to technical components; the case of PROMPT, described in Box 4, could be viewed as an example of this kind of approach.

Other approaches, by contrast, seek to ‘loosen’ the description of the intervention by focusing less on specifying the details of each component and more on the ability of adopters to formulate their own versions of these components in their own setting. This includes approaches that focus on the theory of change underpinning the intervention and that see fidelity as replicating the function that components play within this theory of change rather than their original form. It also includes approaches that focus on the underlying principles and goals of the intervention and allow adopters to work towards their own way of fulfilling these – an example of which can be seen in the case study of Shared Haemodialysis Care at the end of this chapter. Another possible loosening approach is to focus on building the knowledge, skills and capabilities that adopters require to re-create the intervention’s effects in their own setting. In the language of intervention manuals, tightening approaches aim to lengthen the manual, while loosening approaches effectively support the adopter to write their own version.

Box 4: PROMPT: the importance of considering the social aspects of an intervention

PROMPT (Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training) is a one-day, multi-professional training course developed by a team at Southmead Hospital in Bristol. It uses simulation models to address the clinical and behavioural skills required by teams responding to obstetric emergencies. It has been associated with significant improvements in care outcomes, including a 50% reduction in babies born starved of oxygen and a 70% reduction in babies suffering from shoulder dystocia. The training course includes a detailed manual setting out technical components, such as emergency drills for dealing with obstetric haemorrhage, along with some principles for running the training, such as multi-professional participation and the use of props and patient actors.

While PROMPT has spread widely, consistent replication of the successes seen at Southmead has been harder. For example, implementation of PROMPT in one Australian state showed more modest improvements, and not all sites were able to implement it fully. This suggests that the training and the accompanying technical proficiency may not by themselves fully explain the outcomes seen at Southmead. Indeed, a survey of organisations adopting PROMPT suggests that how well a unit implements the package is related to their underlying safety culture and attitudes. This implies that PROMPT is not simply a technical intervention but a ‘social’ one, too, and that successful implementation relies on factors such as the values, behaviours and relationships within the organisations implementing it.

The Health Foundation is now funding new research to characterise the mechanisms underlying the improvements seen at Southmead. The research will also develop and test an additional ‘implementation package’ that incorporates an intervention to support the norms, behaviours and systems that need to be in place to reproduce Southmead’s safety outcomes.

Tightening and loosening approaches both represent attempts to absorb the context-dependent and social nature of complex interventions in order to support their successful implementation. Both also seek to reconcile the need for creativity and constraint, but via different routes. ‘Tight’ descriptions attempt to draw social and contextual factors into the intervention protocols, though in doing so tend to highlight the capabilities required for successful implementation. ‘Loose’ descriptions, by contrast, focus on helping adopters adapt the intervention to fit their own context, though in doing so make them ‘own’ the constraints within which they need to operate.

Whichever approach is taken will have implications for the concept of fidelity. Tight descriptions multiply the number of factors guiding faithful replication of the intervention, and can increase the likelihood that the ultimate form of the replicated intervention will resemble its original incarnation. Employing looser descriptions, by contrast, may well mean that fidelity is seen to reside in features of the intervention other than its original form, for example, in faithfulness to the goals of the intervention or the underlying principles, or in the use of a particular methodology to re-create it. As discussed earlier, loosening strategies also include theory-based approaches to codification, which see fidelity as residing in the function particular components play within the intervention’s theory of change. An example of a theory-based approach to fidelity, from the evaluation of the Health Foundation’s Safer Clinical Systems programme, is described in Box 5.

Box 5: Fidelity and adaptation in the Safer Clinical Systems programme

Safer Clinical Systems was a programme run by the Health Foundation between 2008–2016 to improve the safety and reliability of health care. The programme approach aimed to improve patient safety not by imposing pre-defined solutions on organisations, but by developing their capacity to diagnose system-level weaknesses and introduce interventions to address them. The tools and techniques used were mostly imported from other industries, then adapted and customised for health care. A prominent feature of the programme was its goal of changing the way organisations approached safety, from the prevailing reactive, incident-based approach to a more proactive, risk-based one.

The evaluation of Safer Clinical Systems identified the programme’s theory of change as consisting of two broad components: a stepwise method made up of diagnostic, implementation, measurement and reporting phases; and a proactive and collegial approach to safety. In the final phase of the programme, the evaluators assessed fidelity in terms of divergence from this theory of change. They outlined two types of divergence, which they termed ‘principled deviations’ and ‘conspicuous departures’. Principled deviations ‘served to address local needs and contextual pressures, but did not affect the two core elements of the theory of change’. Conspicuous departures, however, altered the core elements at the heart of the approach and transformed it into something different.

Principled deviations tended to be ‘functional’, allowing teams to overcome local constraints and maintain momentum in their work. For instance, during the diagnostic phase, one team renamed some of the tools and revised the language within them in response to concerns that they were off-putting for staff, while nevertheless maintaining the proactive, collegial and stepwise nature of the approach. The evaluators also saw these principled deviations as attempts by teams to gain ownership of the work and embed it into organisational practice.

In another site, however, the diagnostic phase was conducted by external consultants rather than permanent team members – a conspicuous departure from the programme approach, which had emphasised local ownership. The evaluation concluded that ‘the relationship between fidelity to and effectiveness of the Safer Clinical Systems was not straightforward, but there were indications that principled deviations led to satisfactory outcomes, while more conspicuous departures did not’.

Innovator views on tightening and loosening

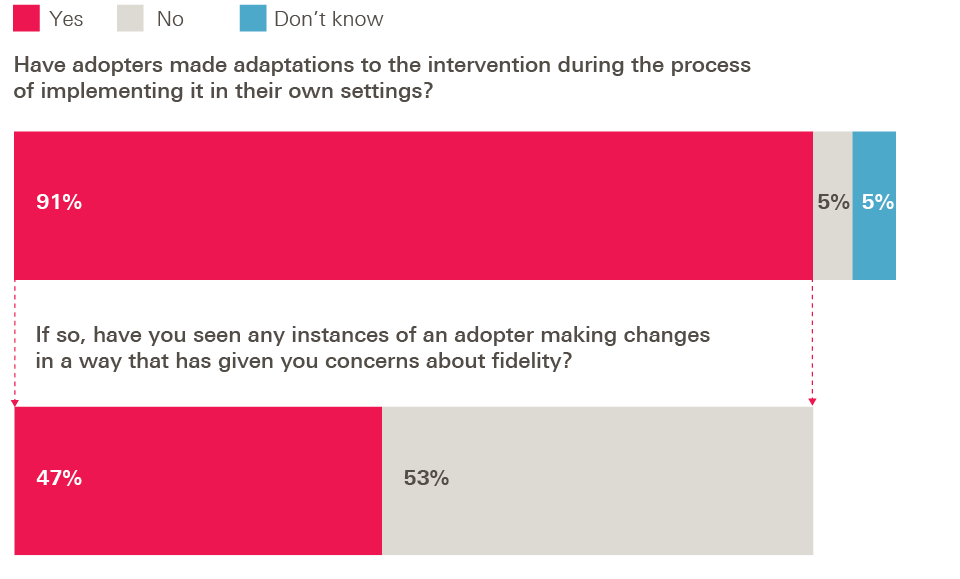

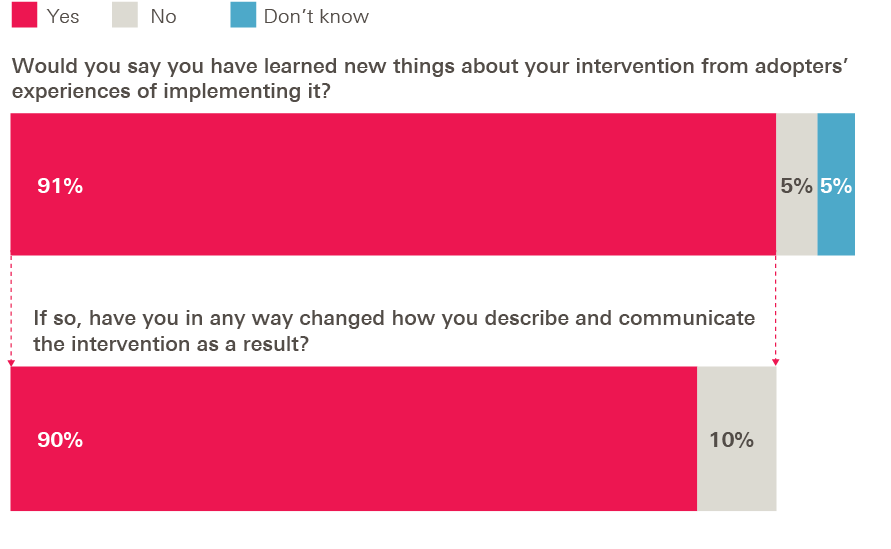

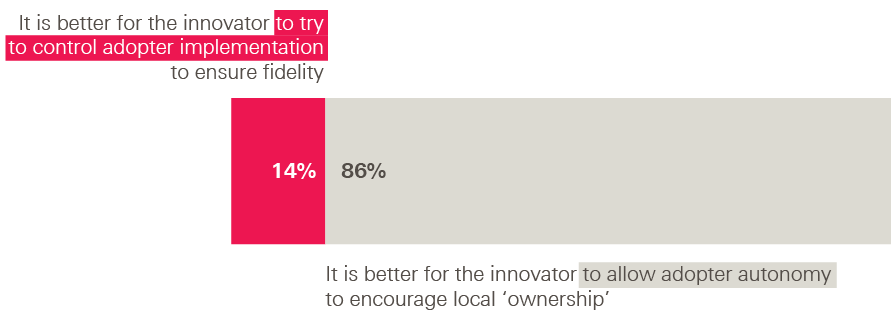

In our survey of innovators from Health Foundation programmes, nine out of ten (91%) said adopters had made adaptations to the intervention during implementation, and nearly half of these innovators (47%) said they had seen instances of changes being made that had given them concerns about fidelity. So, we were interested to see their views on the best route for ensuring effective implementation.

Figure 2: Survey of innovators – adaptations made by adopters

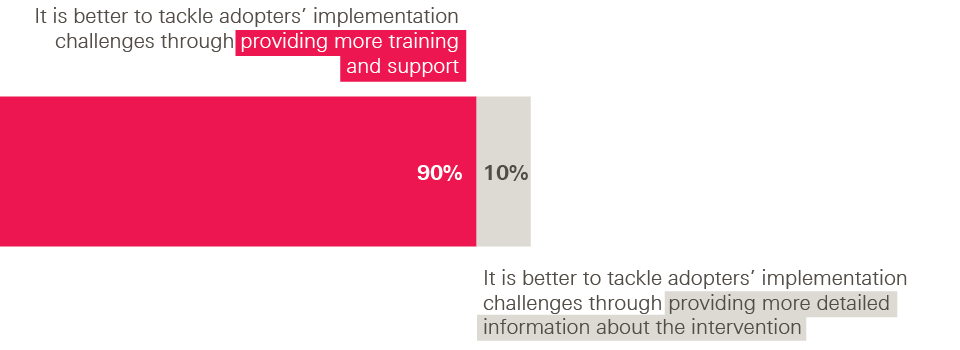

As described above, a ‘tightening’ approach aims to specify more granular and detailed information about the intervention in order to reduce the risk of important factors being missed or changes being made that breach fidelity. A ‘loosening’ approach, by contrast, focuses less on the specific details of intervention components and more on the underlying goals, and on the capability of adopters to re-create their own version of the intervention in their own setting.

What did our innovators think of these approaches? Overwhelmingly, they favoured a loosening approach. When asked to choose between two statements, 90% of innovators chose ‘It is better to tackle adopters’ implementation challenges through providing more training and support to implement the intervention’, with only 10% choosing ‘It is better to tackle adopters’ implementation challenges through providing more detailed information about the intervention’.

Figure 3: Survey of innovators – tackling implementation challenges

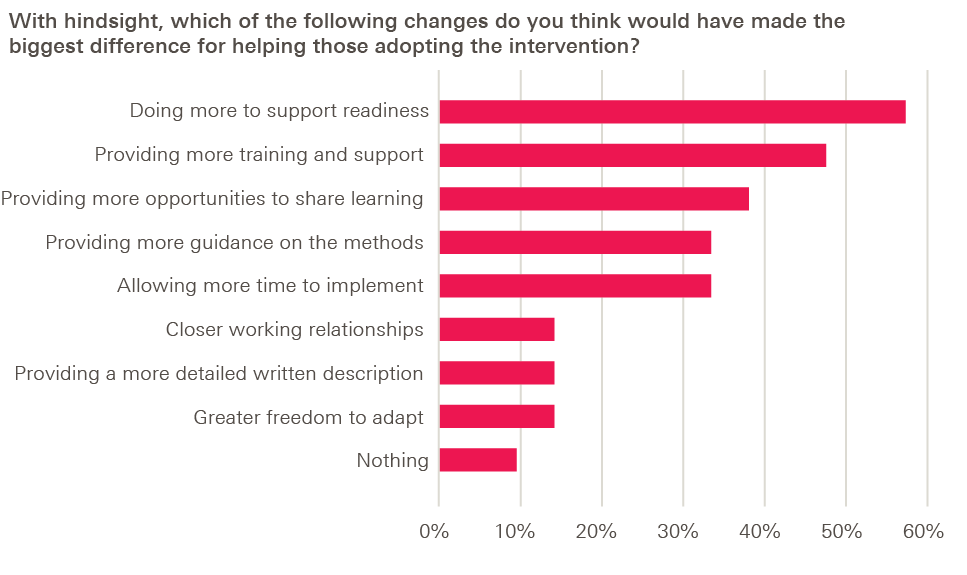

This split was mirrored in innovators’ responses to a separate question, discussed in Chapter 5, about what, with hindsight, would have made the biggest difference for supporting adoption. The most popular options were capability-oriented – doing more in advance to support adopter readiness and providing more training and support – while the option of providing a more detailed written description of the intervention was one of the least popular.

***

There are merits in all of these approaches to intervention description and a priority for improvement research is to investigate which might work best in which circumstances. Interviews with grant holders engaged in the Health Foundation’s programmes highlight both advantages and disadvantages of tightening and loosening strategies. Tight descriptions that seek greater prescription may highlight important factors that support effective replication, but in doing so may make it harder for adopters to feel a strong sense of agency in shaping the intervention. Such approaches could also be open to the accusation that they are seeking a level of determinism over the link between components and outcomes that might be hard to attain in practice. Conversely, loose descriptions that seek greater abstraction potentially allow an adopter more scope for creative responses to contextual issues, but may also make adoption more challenging and risky. Indeed, providing too little concrete information can be daunting for potential adopters, who may yearn for clearer guidance at the outset.

Perhaps for these reasons, successful cases of codification often employ blends of these techniques. For example, specifying the function of different components within a theory of change could be combined with identifying the social and relational factors required to enable those components to function successfully, and which therefore have to be reproduced. Or a capability-building approach could be combined with detailed prescription of intervention components or implementation methods. An example of the latter, illustrated in Box 6, can be seen in the Flow Coaching Academy, which supports teams to improve flow along condition-based pathways using a training approach. A blended model can also be seen in franchising approaches to spreading innovation, (see Box 7), in which detailed manualisation is combined with ongoing training and support. So tightening and loosening strategies are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and can be simultaneously applied to different aspects of interventions.

Box 6: The Flow Coaching Academy

The Flow Coaching Academy supports teams to improve patient flow along condition-based pathways (such as stroke or acute paediatrics), using team coaching and ‘flow’ principles. It was developed from the learning gained in two previous Health Foundation-funded programmes: Flow Cost Quality and the Sheffield Microsystems Coaching Academy.41

Rather than prescribing specific intervention components or outcomes, the Academy instead trains individuals to use a ‘roadmap’ to coach flow improvement within their own organisations. An expert faculty delivers the one-year action learning curriculum at monthly sessions, which involves training in technical skills (such as process mapping) and relational skills (such as resolving difficult situations). This capability-building is combined with the ‘Big Room’ methodology (based on the ‘Oobeya process’, originally developed by Toyota) – a regular, standardised meeting that brings together staff and patients involved in a care pathway to iteratively test ideas, monitor data and progress, discuss issues, share experiences and agree next steps.

Work is now underway to develop a network of 10–12 such academies across the UK.

Box 7: Social franchising

Social franchising enables an adopter organisation to deliver a proven intervention or idea to agreed standards under a franchise agreement. The intervention is packaged up for franchisees to replicate, usually in the form of a manual, accompanied by training and support; in return, the franchisee pays a fee to cover the costs of the franchise operation and shares data and other information with the franchisor. The intervention manual usually sets out the essential components of the intervention, while permitting appropriate local flexibility where this is required for successful implementation.

As a method of replication, franchising sits in the middle of the spectrum in terms of the degree of affiliation between innovator and adopter. At one end of the spectrum, spread could be achieved through the growth of a single organisation, where ownership remains with the innovator; at the other end are approaches with no relationship whatsoever between innovator and adopter, for example where ideas are disseminated through publication and independently picked up by others. Franchising approaches sit somewhere in between: they require a degree of affiliation between franchisor and franchisee through the franchise agreement – both for the accountability of the franchisee to the franchisor and also for the support provided by the franchisor to the franchisee. As such, franchising has the potential to offer greater levels of support to adopters than some approaches to spread, and also greater control to the innovator to ensure fidelity to the original model. Different franchise operations strike different balances between these elements.

It is this combination of manualisation with training and implementation support that makes franchising a good example of a blended approach to codification and replication. It can permit tight specification of interventions and help ensure fidelity, while also recognising the importance of building adopter capability and providing ongoing support.

During 2018 and 2019, the Health Foundation will be testing the feasibility of using social franchising and licensing methods to spread complex health care interventions. Through the programme Exploring Social Franchising and Licensing, four teams are being funded to scale their intervention using these techniques. These range from a pharmacist-led IT intervention (PINCER) for reducing medication errors in general practice prescribing, led by the University of Nottingham, to an integrated care model (the Pathway model) to ensure homeless patients admitted to hospital have access to the care and support they need, led by the homeless health care charity Pathway. There will be a significant evaluation component to the programme, to generate wider learning on the applicability of franchising techniques to health care interventions.

In most discussions of innovation, the innovation itself – the thing that is to be spread – is taken as a given. The implication of the discussion here, by contrast, is that the notion of a health care intervention is to some extent a more moveable feast; it can be conceptualised in a variety of ways (as a set of component activities, capabilities, methods, principles, or a combination of these) and at varying levels of generality or specificity. As the examples above illustrate, exactly how an innovator chooses to characterise their intervention will have implications not only for the notion of fidelity, but also for the appropriate method for spreading the intervention. For example, a capability-based approach may lend itself to using training as a route to spread, whereas a theory-of-change approach will require a process that supports adopters to design their own corresponding version of the intervention.

Adopter views on flexibility versus prescription

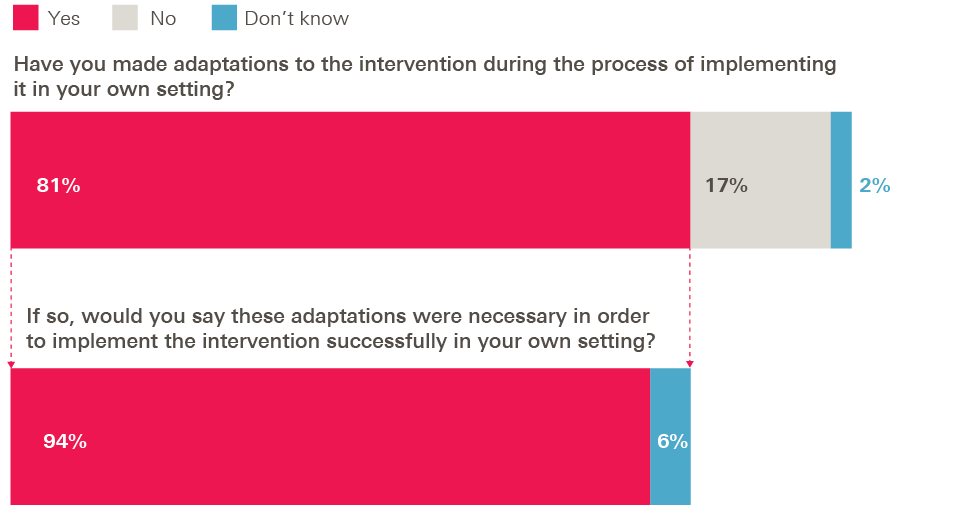

Our survey found mixed views among adopters of the right balance between prescription and flexibility. On the one hand, 81% of adopters in Health Foundation programmes said they had made adaptations to the intervention they were adopting, and nearly all of these adopters (94%) said the adaptations had been necessary in order to implement the intervention successfully in their own setting.

Figure 4: Survey of adopters – adaptations during implementation

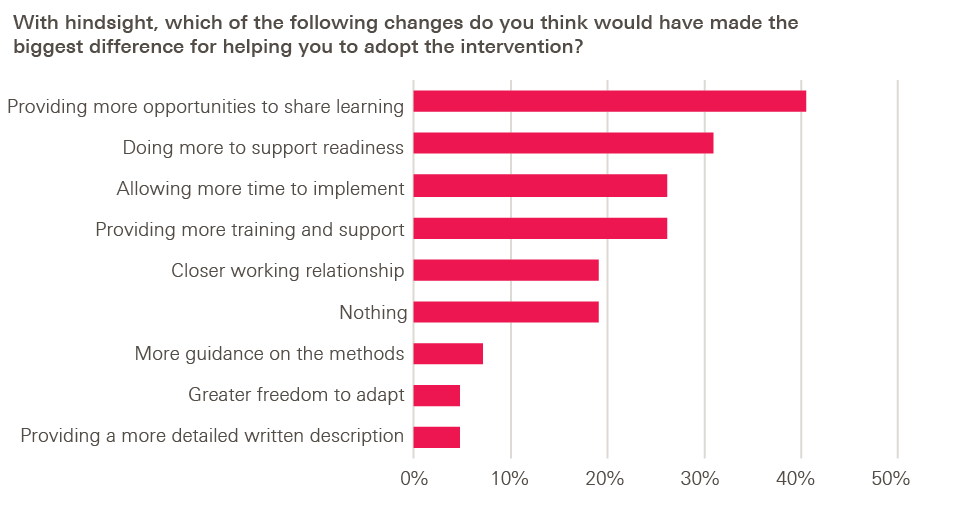

And in response to a further question (discussed in more detail in Chapter 5) about what would have made the biggest difference in helping them adopt the intervention, adopters tended to favour capability-building over greater specification: more opportunities to share learning, more support to ensure adopter readiness and more training were the most popular options, while providing a more detailed written description of the intervention was the least popular.

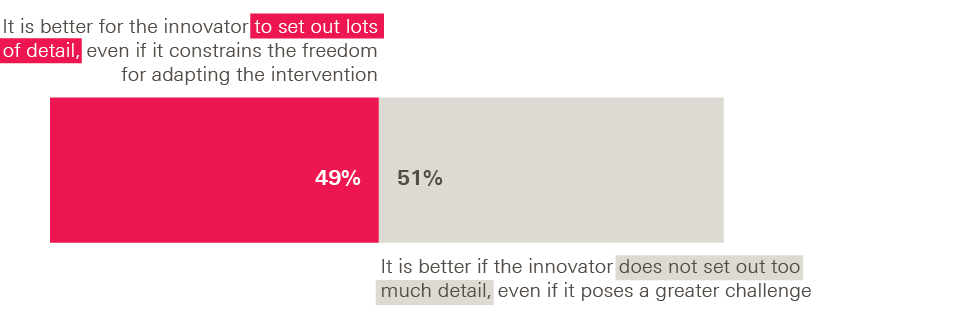

On the other hand, adopters emphasised in interviews that there is a balance to be struck; it can be daunting to implement a new intervention with insufficient information and guidance from the innovator. This sentiment also emerged in our survey, where adopters were evenly split on whether specifying lots of detail was a good thing or not. When asked to choose, 49% favoured the statement ‘It is better if the innovator/programme leader sets out lots of detail about the intervention in order to help others implement it, even if this constrains the freedom for adapting it to new settings’. The other 51% chose ‘It is better if the innovator/programme leader does not set out too much detail about the intervention in order to allow others sufficient freedom to adapt it, even if this poses a greater challenge for those implementing it’.

Figure 5: Survey of adopters – optimum level of detail

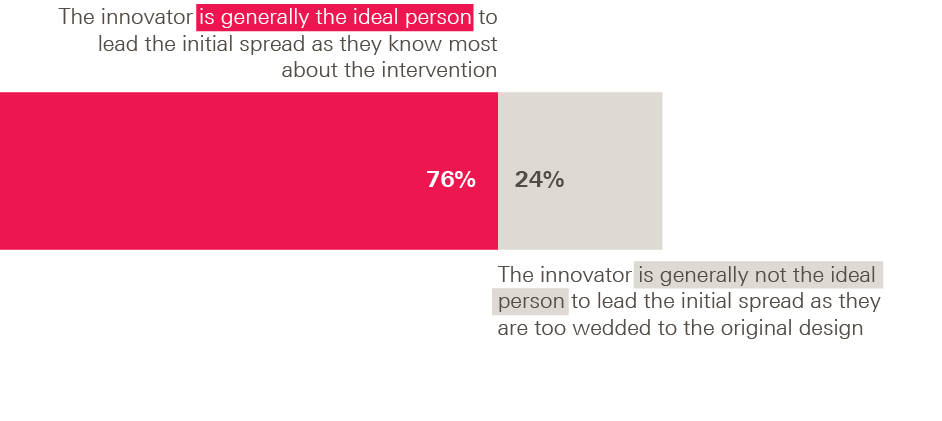

In a related question, three-quarters of adopters (76%) favoured the statement ‘The innovator is generally the ideal person to lead the initial spread process because they know most about the intervention’, with only a quarter (24%) choosing ‘The innovator is not generally the ideal person to lead the initial spread process because they are too wedded to their original design’.

Figure 6: Survey of adopters – leadership of the initial spread process

So, although adopters clearly value flexibility and the freedom to adapt the intervention to their own context, it would be wrong to conclude they want as little prescription as possible or an environment where anything goes.

***

One of the benefits of formative and process evaluations is that they can uncover an intervention’s underlying theory of change and throw light on the role played by various contextual factors in facilitating or hindering an intervention’s success, thereby supporting future replication. However, it is clearly also important for innovators, policymakers and programme leaders – not just evaluators and researchers – to be aware of these approaches to conceptualising and describing interventions in order to codify and spread them more effectively. For example, we would echo others who have advocated greater use of programme theory by innovators and improvers in order to enhance intervention description and promote successful replication.

Despite the fact that it contains rich, practical insights for those engaged in spread and adoption, the majority of discussion of these issues tends to reside in the academic literature on evaluation and implementation science, rather than in literature aimed at practitioners. We believe there is a case for making these approaches to codification a standard part of the innovator’s toolkit alongside more familiar skills such as how to make a pitch or how to design a business case. We would therefore encourage those involved in supporting innovators to scale up their work, and those involved in designing courses for innovators, to incorporate these ideas and approaches to conceptualising and describing interventions.

Case study 1

Shared Haemodialysis Care: From a task-focused intervention to a cultural shift

Haemodialysis is a treatment for people whose kidneys are no longer functioning properly. It involves diverting blood through a machine, where it is filtered to remove waste products and excess fluid, before being returned to the body. Easy access to the blood vessels is necessary. If the treatment is undertaken in a hospital setting it is usually required three times a week. The treatment becomes a major part of people’s lives, with each hospital visit lasting up to four hours, and it can sometimes leave patients feeling powerless and entirely dependent on the health professionals caring for them.

A team working out of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust formalised an intervention called Shared Haemodialysis Care, which gives hospital dialysis patients the opportunity to take a greater role in their own care. Patients are supported to perform any of the 14 standard tasks involved in haemodialysis, such as checking blood pressure, preparing the dialysis machine and inserting needles. Involving haemodialysis patients in their care has been found to empower them and improve motivation, confidence and wellbeing.

From 2016, with funding from a Health Foundation Scaling Up grant, the Sheffield team developed a programme to spread Shared Haemodialysis Care across 12 dialysis units in England, split into two waves of six. This followed a previous initiative that had defined the intervention, as part of the Health Foundation’s earlier programme Closing the Gap through Changing Relationships (2010–2013), which proved essential in providing pilot data and informing plans for the subsequent Scaling Up project.

The Scaling Up project, which ran from 2016 to 2018, was structured as a quality improvement collaborative. It included supporting materials such as a patient competency handbook (to support patients to carry out the standard haemodialysis tasks), posters and leaflets, as well as vehicles for sharing learning such as events, teleconferences, peer networking and an online knowledge-sharing platform. An additional seven sites, including some in Northern Ireland and Scotland, subsequently joined, bringing the total to 19.

The experience of trying to spread the intervention has led those involved to reflect on what Shared Haemodialysis Care actually consists of, and what the essence of the intervention is. As part of the previous Closing the Gap initiative, the programme leaders had specified that ‘doing’ shared haemodialysis required patients to be carrying out at least seven of the 14 haemodialysis tasks (subsequently revised down to five). However, through testing the intervention in multiple sites, the team has discovered that enhanced patient experience is not necessarily achieved by patients carrying out a certain number of tasks, but rather by asking them, ‘What would you like to learn?’ and helping them achieve their goal.

‘Shared care is engaging patients in any aspect of their own care that’s meaningful to them… it’s a concept, really. It’s not a number of tasks that people do.’ Interview with a member of the programme team

This has led the programme leaders to realise that the core of the intervention actually lies in fostering a cultural shift, one where patients and professionals become genuine partners in delivering care, rather than simply teaching patients to perform a certain number of tasks.

‘… When we first started, we thought we were going to find the answer and go, “Oh, bingo”… “This is easy”… It’s much clearer to me now what the essential ingredients are, but it does change and change over time and just recently I’ve… felt, well, this is huge actually, this is a huge culture change, engaging patients in their own care.’ Interview with a member of the programme team

Reflecting the cultural and relational shift that underpins the intervention, the team found that some of the greatest implementation challenges have involved overcoming resistance from staff, who may feel their professional status is threatened, and among patients, who have sometimes been concerned about the security of nurses’ jobs.

So while the tasks remain central to the technical side of Shared Haemodialysis Care and are useful for measurement, the intervention is now conceptualised primarily as a cultural one. In line with this, the intervention is now characterised in a ‘loose’ way, where the emphasis is on achieving an overall goal – supporting patient involvement to a degree that is meaningful to them – and using a capability-building approach to help adopter teams get there. A major focus of the programme is the use of quality improvement methodology, using small tests of change to enable teams to test the intervention and find their own ways forward; teams are supported in improving different aspects of the intervention using PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) cycles, whether that is one of the 14 haemodialysis tasks or aspects of the environment in which care is delivered.

‘… It’s a very loose intervention. I think there’s always a debate about how much you have to know before you start conducting a trial, and how much iteration there can be… There are quite specific ideas around the delivery of care, but [it’s] possibly less specific about how to actually make those changes within a unit.’ Interview with the programme evaluator

And while teams are provided with materials needed to support patients – such as information about the procedures, the patient competency handbook, and so on – programme leaders have encouraged teams to customise these in order to make them suitable to the local setting.

‘… One of the things we learnt… last time, perhaps, was that ‘dissemination by lamination’ wasn’t the thing to do. It wasn’t going to work. This needs to be locally configured by the teams in a way that means something to them, and it would be very different at each site.’ Interview with the programme leader

All of this has meant that, in practice, the intervention looks very different from site to site, though only occasionally has the innovator had concerns about adopters’ interpretations of the original model, such as when one site stipulated that shared haemodialysis could only be performed by patients on a designated ‘shared care’ bed. As a general rule, local flexibility and customisation of the intervention by adopters has been viewed positively by the programme leaders, as both a central aspect of making the intervention work in new settings, and an important source of learning as the intervention spreads further.

‘To just pick up what was happening at Sheffield and say, “Right, this seems to be working at Sheffield. We’re just going to do exactly the same everywhere,” it would be just trying to bang square pegs into round holes all over the country. I think there’d be a lot of resistance. Things clearly wouldn’t work, and they wouldn’t… necessarily be the priorities of the staff. There might be local difficulties which meant that they’d get discouraged.’ Interview with the programme evaluator

‘You’re getting a different perspective on it all the time, aren’t you? I’ve kind of thought that we were all doing similar things, but it turns out everybody has got their own interpretation of it, and learning about and listening to what they’ve got has helped us to understand what the key ingredients actually are, because there were some that were very successful.’ Interview with a member of the programme team

The testing and revision stage

The preceding analysis has highlighted the importance of the context into which an intervention is introduced in determining its success, and thus the need for adopters to be aware of relevant contextual factors when attempting to replicate the intervention.

But it can be hard for innovators to ‘see’ their own context. When something has been achieved successfully in one location it might seem straightforward to document the actions involved, but it may in fact be impossible to know which aspects of context were relevant to the initial success without being able to compare this experience against other counterfactual scenarios. It may therefore be only when an intervention is implemented in new contexts that the comparative information becomes available to enable the innovator to understand what actually made their intervention work first time around.