Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Siva Anandaciva, Jennifer Dixon and Sarah Scobie for their comments on earlier drafts of the paper. Errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors alone.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2021-P08

Key points

- COVID-19 has been the biggest shock in the NHS’s history and its impacts on people’s health and the health service will be felt for many years. This report assesses progress on the main pledges in the NHS Long Term Plan and the impact of COVID-19 on their delivery.

- In 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan set out a 10-year strategy for improving and reforming the NHS in England. The plan aimed to expand primary and community services, strengthen action on prevention and health inequalities, and improve quality of care for people with major diseases. Collaboration between local services was to help drive this progress.

- No part of the NHS’s plan has been unaffected by the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, the overall picture is one of major delay, disruption, and increased demands on services. There have been delays to developing planned new services in primary and community care, and widespread disruption to elective care, cancer screening and treatment, mental health care, and other services, with serious consequences for people’s health and wellbeing.

- The plan committed to maintaining and improving performance in hospital waiting times, but performance was declining even before COVID-19 hit. The pandemic had a major impact on hospital services, particularly in the first half of 2020. Although many non-COVID-19 services remained open and many others have been restored to pre-pandemic levels, there is a large backlog of unmet health care needs. Waiting lists for hospital care are the worst on record, at over 5.45 million at the end of June 2021, while only two-thirds of community services are reported to have been fully restored.

- The pandemic has also created new demands for NHS services beyond immediate COVID-19 care, including additional mental health needs and chronic side effects of COVID-19. Previous national targets – such as for expanding access to mental health services for adults and children – will need to be revisited to account for greater need.

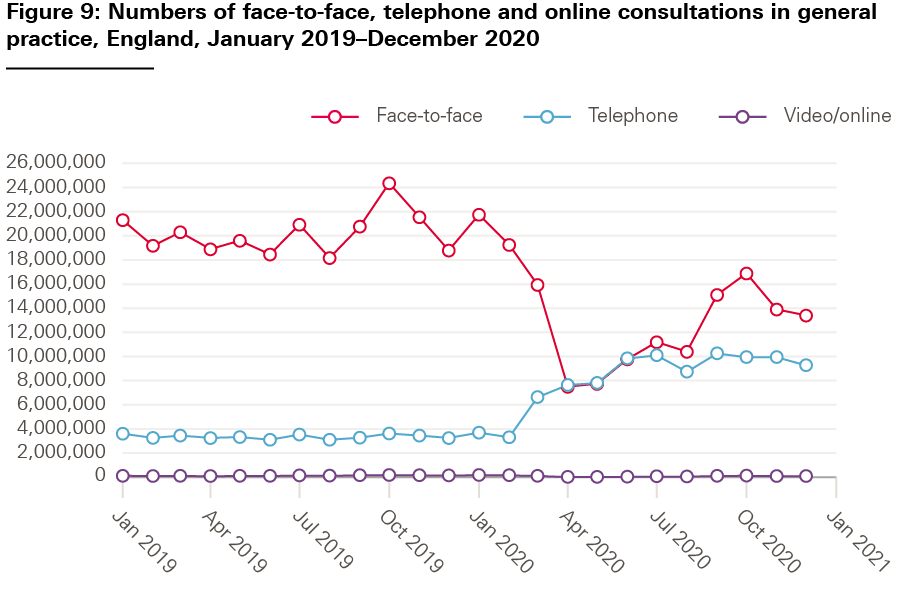

- Some long term plan commitments have been accelerated by the COVID-19 response, such as improving access to remote consultations in primary care and outpatients. But these changes will need careful monitoring and evaluation to ensure that they meet their intended aims and do not exacerbate inequalities.

- COVID-19 has exposed and widened existing inequalities in health and care in England. The long term plan lacked detail on how inequalities would be reduced – and local plans to tackle inequalities were delayed before the pandemic. A more detailed framework of priorities, interventions, and measures for NHS agencies on tackling inequalities is now needed to ensure greater awareness of inequalities is translated into tangible action to reduce them.

- New partnership structures have been developed to help local agencies improve care, including integrated care systems (ICSs) and primary care networks (PCNs). PCNs have been vital to delivering the COVID-19 vaccination programme. But COVID-19 has held back the broader process of redesigning care to improve health and reduce inequalities, which is at the core of the NHS Long Term Plan.

- The Health and Care Bill 2021–22 will introduce changes to NHS structures in England – including formalising local partnerships. But the health system needs an updated strategy for improvement and reform that accounts for the massive disruption caused by COVID-19. This must confront hard trade-offs. Action to address the backlog in elective care must not come at the expense of interventions to prevent disease and reduce inequalities in health and care.

- Making progress depends on government decisions about investment and reform. Before the pandemic, government failed to provide the NHS with the long-term investment needed to expand the workforce and improve NHS infrastructure. Without enough staff and adequate buildings and equipment, the NHS will not be able to recover services after the pandemic.

- Significant additional investment has been promised, but major unknowns around the future course of the pandemic mean there is considerable uncertainty over whether this will be sufficient. Projections suggest the NHS England budget needs to increase by at least £7.1bn in 2022/23, not including the substantial additional funding that may be needed to cover any immediate costs of dealing with COVID-19 and the virus having an ongoing impact on the NHS’s ability to deliver care. This is the minimum required to put the NHS on course to tackle the growing backlog of treatment by 2024/25, cover increases in underlying pressures, the costs of implementing existing long term plan commitments, and meet increased demand for mental health services.

- After repeated delays, plans for a cap on social care costs were eventually announced in September 2021. While a bold and positive step forward that will start protecting people from incurring catastrophic costs, this falls well short of what is needed to stabilise the current system and deliver the comprehensive reform needed to fully deliver the Prime Minister’s promise to fix social care once and for all.

- Wider reform is also needed to improve population health and reduce inequalities. Government currently has no national strategy for reducing health inequalities in England and public health budgets were 24% smaller per capita in 2021/22 than 2015/16. Increased investment in the NHS must go alongside investment in the wider services that shape health.

Introduction

If the pandemic had not struck in early 2020, the NHS in England would have been into the third year of its 10-year programme of reform and improvements to services set out in the NHS Long Term Plan.

The long term plan was drawn up in response to a 5-year funding commitment made by Prime Minister Theresa May in 2018, on the 70th anniversary of the NHS. In a speech delivered at the Royal Free Hospital in London, May said that past funding increases had been ‘inconsistent and short-term’, and that the NHS needed to be able to ‘plan for the future with ambition and confidence.’ May committed to increase the NHS budget by 3.4% in real terms between 2019/20 and 2023/24, and in return asked the NHS to develop a 10-year plan for reform.

Those plans were developed and consulted on by NHS England over the next 6 months, with the NHS Long Term Plan published in January 2019. The plan sets out a vision for better care in the community, improved treatment for major conditions such as cancer and mental illness, improved waiting times, more action to prevent ill health and reduce inequalities, and better use of technology. This was to be achieved through a mix of policy approaches – including stronger partnerships between the NHS and local government to lead local service changes, and new collaborations of general practices to provide more integrated care.

Overtaken by events

The proposals in the long term plan were built on May’s 5-year funding pledge, and on the expectation that multi-year funding settlements for the Department of Health and Social Care would be set later in 2019 – covering public health, education and capital. The plan also anticipated the reform and investment promised by government for adult social care in England.

But events since the plan published have been turbulent. On 24 July 2019, Boris Johnson was appointed Prime Minister, and in October a general election was called. The Conservative manifesto recommitted the government to the existing NHS funding increases but added more priorities for the NHS, including new hospitals and additional GP appointments. The day after his victory at the polls on 12 December, the re-elected Prime Minister declared the NHS to be ‘this one nation Conservative government’s top priority.’

Less than 3 months later, the UK recorded its first death from COVID-19. By June 2021, COVID-19 had claimed over 150,000 lives in the UK, hospitalised over 460,000 people, and left a million reporting persistent symptoms after infection. Even though the government released billions of pounds to protect people’s lives and livelihoods, the effects of policies to control the virus, including lockdowns and social distancing, have damaged the economy. Employment began to rise as the economy reopened in 2021, but by May 2021 there was still an estimated employment gap of 4.5 million people compared with the pre-pandemic period. The negative impact on people’s finances and wellbeing has been felt most acutely by the most socioeconomically disadvantaged, younger people, and the self-employed.

The disruption to health and care staff and services has been severe. At the peaks of the pandemic, many NHS staff were redeployed to care for COVID-19 patients. Infections among staff have caused illness and death, and exacerbated staff shortages. Infection control measures have required wholesale changes to how services are delivered (and to whom) across the health and care system. The result has been delays to routine care and a rapidly growing backlog of unmet need. In social care, staff have also experienced high mortality and illness from COVID-19, and, like NHS staff, have experienced high levels of stress.

In response to the crisis, the government has spent heavily. The National Audit Office estimates that £172bn has already been spent out of £372bn that government expects to spend (as at May 2021). This includes support for businesses, individuals, and health and care services. Although the government has committed to protect the 5-year NHS spending plans, it is facing additional costs likely to run into billions of pounds over several years to meet new demand arising from the pandemic and to reduce the backlog of care. Economic uncertainty has meant short-term, 1-year funding commitments for public health, capital and education, and similar short-term funding for social care and local government.

The long term plan remains the blueprint for the NHS’s evolution, but the pandemic has dealt a huge blow to both the NHS and social care. In what follows, we assess the overall progress of the main pledges in the NHS Long Term Plan and the impact of COVID-19 on their delivery. We provide a narrative of what was achieved before the pandemic, assemble the evidence of how the pandemic has affected progress against the different components of the plan, and identify implications for the future as the NHS and government plans its recovery from the pandemic.

Approach and methods

In this report, we provide a narrative overview of the main developments following the publication of the NHS Long Term Plan in 2019 to June 2021. We then offer an assessment of the progress made against the main commitments in the plan.

The plan contains a large number of pledges and promises in its 136 pages (estimated to contain more than 100 commitments and 500 general ambitions). To assess progress, we focus on the indicators specified in NHS England’s implementation framework, published in June 2019 (shown in full at Annex A), and which also feature on NHS England’s website as ‘Long Term Plan Headline Metrics’.

Finally, we offer some analysis of what this means for the timing and ordering of what the NHS aimed to do in the long term plan, over 2 very different years ago.

Methods

Our analysis is based on publicly available data and documents. For the narrative of events, we used our COVID-19 policy tracker, covering events in 2020, supplemented by searches of government and other websites for developments since. We used a mix of data to assess progress. Where there are specific datasets referred to in the long term plan, we used these to assess how far national commitments had been delivered. Where new measures were promised but are yet to be developed, we used other national datasets on the same topic (for example, findings from the NHS staff survey on wellbeing in lieu of a new wellbeing metric).

Where data were missing, we accessed NHS England press releases, board papers, annual or other reports, and submissions to parliamentary committees or questions. For additional context, we also looked at reports produced by professional organisations and patient charities, in addition to relevant publications by official bodies, including the National Audit Office, Healthwatch and the Care Quality Commission.

Our assessment only provides a limited picture. We focus on the ‘headline metrics’ in the plan, which do not include commitments and general ambitions to improve care for major conditions including stroke, cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and other areas. Gaps in data make it difficult to assess progress in some of the priority areas. And new data on progress against different aspects of the long term plan are always emerging; the main analyses were based on data collected between February and May 2021, and as a result may have omitted more recent data. Nonetheless, the report attempts to give a comprehensive overview of COVID-19’s impact on the long term plan so far.

What was promised in the plan?

The long term plan built on existing goals from the NHS’s previous national plan – the Five year forward view (published in 2014) – and existing national strategies for cancer and mental health. It was structured around the following six themes.

1. ‘A new service model for the 21st century’

The plan promised that outpatient services would be redesigned to reduce the volume of attendances by a third. Local general practices would come together to form primary care networks (PCNs) (each covering between 30,000 and 50,000 patients) and be funded to employ additional staff, intended to achieve a set of targets ranging from earlier cancer diagnosis to action on reducing health inequalities. Community services would receive additional funding to deliver quicker rehabilitation and crisis services. For acute hospitals, action would be taken to improve urgent care, shorten emergency stays, update waiting time targets (via a review of clinical standards) and improve hospital discharge in collaboration with local government.

2. ‘More NHS action on prevention and health inequalities’

The plan committed new funding to expand NHS prevention programmes, including obesity, smoking cessation and to reduce alcohol-related hospital admissions. On inequalities, more accurate allocation of funding to local areas according to unmet need and inequalities was promised. Local ‘systems’ (now called integrated care systems (ICSs)) would be required to draw up plans to reduce inequalities in return for their funding allocations. There would be some national priorities for local systems to include in these plans, such as reducing inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities, homeless people and those with severe mental illnesses.

3. ‘Further progress on care quality, access and outcomes’

The plan set out actions to improve outcomes for specific diseases and provide better services for particular age groups. On diseases and conditions, the plan promised earlier diagnosis of cancers, expansion of mental health services underpinned by ringfenced increases in funding, and better treatment for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Pregnant women, children and people with learning disabilities were promised improved care and better outcomes, while action on behalf of everyone who need planned hospital treatment would reduce long waiting times.

4. ‘NHS staff will get the backing they need’

A multi-year plan to increase the number of staff and boost access to training and development was promised, but not set out. The plan would be finalised once Health Education England had received its funding allocation from government for the following 5 years, and would be consolidated into a comprehensive People Plan. Meantime, the long term plan committed funding for increasing clinical placements until 2021/22 and an international recruitment campaign. There would also be work to improve conditions for existing staff, ranging from increased access to continuing professional development to improvements in the culture within organisations.

5. ‘Digitally-enabled care will go mainstream across the NHS’

The plan promised investment that would bring, over the next 10 years, widespread access to digital services for patients and more patients and clinicians being able to access and manage records online. Better data and analytic tools would be available to individual clinicians and those planning services within ICSs.

6. ‘Taxpayers’ investment will be used to maximum effect’

All the improvements and reforms set out in the long term plan were costed by national NHS agencies and estimated to be within the additional funding allocated to the NHS by government in 2018. Nevertheless, national NHS leaders assumed that productivity improvements of at least 1.1% a year would continue, administrative costs would be reduced and that all NHS organisations would return to financial balance.

Implementation timetable and key events (2019–2021)

The NHS Long Term Plan expected 2019/20 to be a ‘transitional year’. Progress would be made on some commitments and the groundwork laid for the shift towards ‘system’ working, in which many of the existing sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) – geographically based groups of NHS providers, commissioners, and local government, responsible for leading local service changes – would begin their transition to ICSs (see section on Integrated care systems). Later in January 2019, local systems received their financial allocations for the 5-year period (2019/20 to 2023/24). In return, they were asked to develop local plans for delivering the long term plan commitments.

NHS England offered to help ICSs with this process, including ‘intensive support for the most challenged systems’. The long term plan emphasised the need for organisations to collaborate to improve care and manage resources, not pursuing objectives to benefit their own organisations at the expense of others. The plan also described the need for legislative change to support progress on delivering its objectives, and set out a series of proposals (including rolling back NHS competition rules and establishing a firmer legal basis for local partnership working), which were put out for wider engagement the following month.

In June 2019, NHS England published an implementation framework, containing detailed guidance for local areas about to draw up their 5-year plans. STPs and ICSs were instructed to complete these by November 2019, and the plans were to be incorporated into a national implementation plan by the ‘end of the year’. This was intended to allow the national plans to ‘…properly take account of the government Spending Review decisions on workforce education and training budgets, social care, councils’ public health service and NHS capital investment.’

NHS England continued to draft proposals for the legal underpinning it argued was needed to deliver the long term plan. In September 2019, NHS England published recommendations to government for an NHS bill, based on the findings of an engagement process that had begun in February 2019. NHS England reported strong support for repealing legislation relating to NHS competition and procurement, and recommended statutory guidance for the creation of joint committees running ICSs.

At the end of January 2020, a year after the publication of the long term plan, the NHS Operational Planning Guidance was published. The guidance noted that 2020/21 was going to be a ‘critical year’ in creating new ways for the NHS to work as a system. The guidance set out a revised timetable for local plans, which had not been published at the end of 2019 as promised. These were now due by April 2020. A people plan was due ‘in the coming months’, after which a national implementation plan would follow.

The arrival of COVID-19

Less than 2 months later, COVID-19 had plunged the NHS into an unimaginably different world. By mid-March 2020, although confirmed COVID-19 cases were still under 1,000 in the UK, modelling was predicting a huge surge of illness and deaths: if no action was taken, health services would be overwhelmed. Even with a combination of suppression measures, such as population-wide social distancing, pressures on hospitals were expected to be severe.

On 17 March, the NHS took widespread action to free up staff and beds in anticipation of the coming surge. NHS England asked hospitals to postpone non-urgent operations for 3 months from mid-April at the latest and to urgently discharge all patients deemed ‘medically fit’ to leave. Community services were given responsibility for leading the care of discharged patients and funding was promised for any social care that might be needed. Hospitals were told to continue emergency admissions, urgent cancer care and other types of clinically urgent services. General practices were also asked to switch as much care as possible to remote forms, with face-to-face consultations only if absolutely necessary. Long term plan deadlines for ICS plans, the clinical standards review and the national implementation plan were dropped.

On 29 April, NHS England paid tribute to the ‘fastest and most far-reaching repurposing of NHS services, staffing and capacity in our 72-year history’, which had allowed the NHS to care for over 19,000 inpatients per day with COVID-19, and continue to deliver other essential services. The letter also noted that there had been steep falls in non-COVID-19 emergency admissions (as well as the expected drop in non-urgent activity) and called for local areas to ‘step up’ non-COVID-19 emergency care and start planning to restart routine elective care, while maintaining capacity in case of a COVID-19 resurgence.

Over the summer of 2020, cases, hospitalisations and deaths from COVID-19 continued to fall. On 19 June, the UK’s COVID-19 alert level was dropped from 4 to 3, meaning that the virus was in general circulation but no longer rising or increasing exponentially. At the end of July, NHS England declared that a ‘third phase’ of NHS pandemic response should begin, with the aim of returning non-COVID-19 services to normal levels as soon as possible, while planning for winter pressures, including a possible COVID-19 resurgence. Some of the long term plan priorities were to be resumed for PCNs, community and mental health services, and services for people with learning disabilities.

During the summer lull in infections, the government announced a major reorganisation of Public Health England, which had led the response to COVID-19 and is also responsible for prevention and screening. On 18 August , the former Secretary of State for Health and Social Care announced the abolition of Public Health England and the creation of a new UK-wide organisation, the National Institute for Health Protection (subsequently renamed The Health Security Agency), to improve the response to COVID-19 and future threats to public health. The secretary of state promised to ‘consult widely’ on the future of Public Health England’s ‘incredibly important’ role in health improvement and prevention.

The second wave hits

There was to be no ‘fourth phase’ letter. Instead, on 4 November, NHS England announced a return to an incident ‘level 4’ (the highest level) in the face of rising cases and hospitalisations. Shortly before Christmas, NHS trusts were advised by NHS England to mobilise all their available surge capacity, prioritise ‘timely and safe’ discharge, and make full use of the independent sector and other available capacity to continue to treat as many elective cases as possible, while maintaining urgent non-COVID-19 services. General practice was urged to maintain pre-pandemic appointment levels, at the same time as assisting with vaccinations, described as the ‘highest priority task’ for PCNs for the foreseeable future.

On 4 January, the chief medical officers of the UK warned that there was a ‘material risk’ of the NHS being overwhelmed within 21 days if no action was taken. The same day, the Prime Minister announced a third lockdown for England.

In its board meeting on 28 January, NHS England’s performance update captured the enormity of the second wave of COVID-19: 33,000 patients with COVID-19 in hospital beds in England, and over 250,000 cared for since the pandemic began. Even though NHS organisations had tried to keep as many non-COVID services open during this peak as possible, the January board papers reported that 200,000 patients had waited more than a year for routine hospital treatment (this was over 330,000 by May 2021).

By early March 2021, cases and hospitalisations had begun to fall again. Government committed to a gradual relaxation of lockdown restrictions, extending the duration of emergency economic support to millions of employees and businesses. On 3 March, the Chancellor unveiled a Budget that added a further £65bn to support the economy over the next 2 years on top of the £270bn already committed. 2 weeks later, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care announced that the NHS would be receiving an additional £6.6bn for the first half of 2021 to meet COVID-19-related costs. But there was less generosity towards other sectors crucial to delivering the long term plan. The public health grant for local authorities (announced on 16 March) of £3.3bn for 2021/22 represented only a small (£45m) increase on the previous year, and a real-terms per capita reduction of 24% compared with 2015/16.

After analysing the public spending commitments in the Budget for departments not protected by previous funding arrangements (defence, the NHS and schools), the Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that unprotected budgets faced real-terms cuts of around 3% between 2021/22 and 2022/23. This includes local government, a key partner in many of the long term plan pledges on prevention and reducing health inequalities. The promise to reform adult social care was repeated in the Queen’s Speech on 11 May, but was not linked to a potential bill.

Rising expectations

On 16 March 2021, the government announced its expectations for the health service for the next year, via the 2021/22 ‘mandate’ to NHS England. This included delivering the commitments made in the Conservative party’s 2019 election manifesto, such as 50,000 more nurses, alongside continuing the response to COVID-19 and resuming work to implement the long term plan. Together with a new annex of ‘headline commitments’, the updated mandate added substantially to what the NHS was expected to deliver – with additional priorities effectively set through the inclusion of new metrics to assess progress. The accompanying planning guidance, published on 25 March 2021, specified that local systems work together to support staff recovery, address inequalities, maintain the response to and recovery from COVID-19, and accelerate delivery against the commitments in the long term plan. Despite lingering uncertainty about the future course of the pandemic, ICSs were tasked with developing plans for the year ahead by 3 June 2021.

Progress against the plan

In the sections that follow, we assess the NHS’s progress against the goals set out under the long term plan’s six themes. For each theme, we take NHS England’s ‘headline metrics’ for the plan and use available data to assess progress. We also include evidence of how relevant services have been affected by the pandemic. The implications are explored in the Discussion.

1 A new service model for the 21st century

Summary

- Official measures of progress for developing new service models were mostly undeveloped. The one concrete measure was for an increase in the percentage of overall NHS revenue spent on primary and community services. Other measures, such as patient reported access to primary care and development of new community teams, were ‘to be confirmed’.

- New PCNs were established by July 2019. These involve the large majority of GP practices, contracted to deliver defined services. The pandemic disrupted general practice, forcing changes to the way care is delivered. PCNs have played a key role in vaccine delivery, but there have been delays to implementing four out of the seven new PCN services.

- New ‘rapid response’ community services were piloted before the pandemic hit. COVID-19 brought disruption to all community services, some of which had to be suspended. In June 2021, NHS England reported that 59% of services were fully restored. The pandemic also brought an increased role (and funding) for community services in discharging patients from hospital. A 2-hour rapid response service is now expected to be in place by March 2022.

- NHS England’s accounts for 2019/20 suggest the share of NHS revenue spent on primary and community services increased, but the pandemic has complicated funding flows across the NHS. Demand for primary and community care services remains high, and the extent to which the additional long term plan funding will meet need is not clear.

The long term plan promised to ‘finally dissolve the historic divide between primary and community services’. Investment in primary medical and community health services was to increase as a share of NHS spending over 5 years. GP practices were to be brought together into PCNs, covering populations of around 30,000 to 50,000 people, with formal agreements between practices and the capacity to hold contracts with NHS England.

Billed as an ‘essential building block of every Integrated Care System’, PCNs would coordinate and deliver new services for their local populations, such as earlier cancer diagnosis and better health care for care home residents. The details were to be set out in seven ‘service specifications’ to be finalised after further consultation with the sector. PCNs were expected to work closely with community services to deliver more coordinated care and support.

In parallel, the community services working most closely with acute services were expected to become more responsive with ‘the ambition of freeing up to a million bed days’. Within 5 years, all community health crisis response services were to be available within 2 hours of referral (where clinically appropriate), with reablement care for eligible patients within 2 days of referral.

Progress prior to the pandemic

More detail about how PCNs would work was set out in a new GP contract, published in January 2019. Although technically voluntary, the new contract created powerful financial incentives for practices to sign up to the new networks. £1.8bn of the £2.8bn additional 5-year funding to primary and community care was accessible only via the new PCNs.

PCNs formed rapidly. Over 99% of GP practices came together into over 1,200 PCNs by September 2019. While many practices were already in some form of collaborative relationship, the formation of the new, nationally specified networks involved considerable work to build relationships and set up new governance arrangements to meet a tight deadline.

The seven service specifications for PCNs were agreed prior to the pandemic. These covered medication reviews, improved care in care homes, earlier cancer diagnosis, ‘anticipatory’ care for patients with complex needs, ‘personalised’ care (such as ‘social prescribing’ programmes to link patients with non-medical services), improvements in cardiovascular care, and action on inequalities. Revisions were made after the profession raised concerns about their capacity to deliver the specifications with the available resources. Changes included cutting back requirements for structured medication reviews, agreeing extra payments to cover workload associated with nursing homes, and postponing the personalised and anticipatory care specifications until April 2021.

Once formed, PCNs could access funding to recruit additional primary care professionals, including social prescribing link workers, pharmacists and physiotherapists to meet the long term plan commitment of 26,000 additional staff over 5 years. The range of roles that PCNs could recruit has broadened, and the amount of funding available for recruitment increased. Data on progress against these commitments are incomplete, making it difficult to track progress. An early milestone was to recruit 1,000 social prescribers by the end of 2020: by this date, 852 full-time equivalent (FTE) link workers were in post, but only 60% of PCNs had reported data to NHS Digital.

Pilots of new rapid response community services were launched in seven areas in January 2020, with a plan to begin rolling out the new services nationally from April 2020. However, the long term plan commitments on community services were expected to be implemented over a longer timeframe, with a substantial increase in capacity needed to achieve the 2 hour/2 day standards by 2023/24.

Impact of the pandemic

Major changes were made to primary and community services in response to the pandemic. These aimed to maintain ‘COVID secure’ access to essential services, while supporting acute hospitals to manage the expected surges in critically ill patients.

All GP practices were instructed to switch to a non-face-to-face appointment system and offer remote consultations, seeing patients in person when deemed clinically necessary. Many practices used their PCNs to set up a designated local ‘hot’ site, where suspected COVID-19 positive patients could be seen. The pandemic brought delays to four out of the seven service specifications that were due to start in April 2021, including action on prevention, cardiovascular disease diagnosis and health inequalities. From November 2020, NHS England used the PCN structure as the backbone of the mass vaccination campaign – coordinating staffing, logistics and data.

Community services were tasked with supporting the rapid discharge of patients from acute hospitals with the aim of freeing up 15,000 beds for patients with COVID-19 by the end of March 2020. ‘Discharge to assess’ arrangements were put in place for patients who were expected to need support after leaving hospital: assessments took place in patients’ homes (instead of hospital) and arrangements made for any therapy, care and equipment they might need. Funding was provided by the NHS, with financial eligibility assessments temporarily suspended for social care and NHS continuing care. Services were expected to be reprioritised to free up staff and ensure infection control. This included a complete stop for NHS health checks, and a ‘partial stop’ for a wide range of services where providers were expected to segment patients to continue services for those at highest risk. Other services, such as end of life care, were advised to continue and ‘prepare for increased demand’.

Primary and community services face a daunting set of challenges in the wake of COVID-19. While NHS England believes that the pandemic ‘has proven beyond doubt the value and potential of PCNs’, they are still relatively new entities. There is a need for continuing support to develop managerial skills within PCNs and increase capacity to engage strategically with larger local partners, particularly ICSs.

PCNs are also expected to have recruited 15,500 new FTE roles by the end of 2021/22. Latest data (from the 68% of PCNs reporting staff numbers) suggest just over 5,000 new FTE staff were in place by the end of March 2021. Barriers to PCNs recruiting new staff are not yet fully understood. PCNs will continue to play a central role in the COVID-19 vaccination programme for the foreseeable future, at the same time as their constituent practices manage a rebound in demand for appointments. In March 2021, 28.4 million appointments took place in general practice, compared with 24 million in March 2020.

The community services dataset shows a fall in overall contacts in community services, but gaps in data from before the pandemic make it hard to interpret the trend in activity. Most community services are thought to have backlogs of people waiting for non-COVID-19 care, but the number waiting cannot be quantified. In June 2021, NHS England reported that in six out of seven regions at least half of their community services were at pre-COVID levels or higher and 59% of services were ‘fully restored’.

Implementation of the 2 hour/2 day standards was delayed, with technical guidance on measuring performance not published until November 2020. Data collection began in July 2020, but not all areas are submitting data. The discharge to assess model has now been made permanent, although the funding for services after discharge from hospital was reduced from 6 weeks to 4 with no funding commitment beyond July 2021. NHS England collect data on the number of people discharged, how quickly and where to, but these are not published.

Leaders of NHS community services have raised concerns that there may not be enough capacity to deliver the long term plan commitments alongside discharge to assess, restoring normal services and the anticipated increase in demand for rehabilitation services for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19. The 2021/22 planning guidance promised additional funding to support an accelerated rollout of the 2-hour crisis response standard by April 2022, contingent on operational plans and commitments to submit complete and accurate data to the Community Services Data Set.

Integrated Care Systems (ICSs)

Summary

- NHS England aimed to establish ICSs in every part of England by 2021. It set a headline metric of increasing the ‘percentage of population covered by ICS’.

- By this measure, the plan’s goal has been achieved: NHS England announced that all local systems had become ICSs by March 2021. But exactly what an ICS is and how they differ from previous arrangements has not always been clear.

- The pandemic brought delays to the process of drawing up and publishing ICS plans to improve services and population health. NHS England expects ICSs to lead the recovery of local NHS services, especially the reduction of the backlog for hospital treatment.

- Legislation has been introduced to formally establish ICSs as new NHS agencies in April 2022. This will strengthen the powers of local partnerships but may also cause disruption.

The long term plan described ICSs as ‘central’ to delivering its objectives. ICSs were not new and built on existing partnerships called STPs, made between NHS agencies, local government, and others in 44 areas of England. NHS England described ICSs as more ‘mature’ versions of STPs – and the long term plan committed to establishing them across England by April 2021. ICSs would be responsible for coordinating local services and improving population health.

The plan set out expectations for what ICSs should look like. Each ICS would have a partnership board with representatives from NHS commissioners, providers, PCNs, local authorities, the voluntary and community sector, and others. They would also have a non-executive chair, ‘sufficient’ clinical and management capacity, and needed to achieve ‘full engagement’ with primary care (including through a named accountable clinical director of each PCN). NHS commissioning arrangements would be ‘streamlined’ to align more closely with ICSs, which would ‘typically’ mean clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) merging to fit ICS areas. Wider policy changes were promised to support the shift to ICSs, including a greater emphasis on system working in CQC inspections.

The plan set out how ICSs would be developed within current NHS rules and structures. But it also argued that legislative changes were needed to ‘significantly accelerate progress’ on local integration, and included a list of proposed legal changes. These included establishing ICSs as formal partnership boards and removing ‘overly rigid’ competition and procurement rules.

All local systems – whether currently STPs or already ICSs – were expected to produce 5-year plans for how they would deliver the plan’s objectives later in 2019.

Progress prior to the pandemic

NHS England developed and published further guidance for ICSs throughout 2019. In June 2019, NHS England published a basic framework for how ICSs were intended to work. It described three different levels for decision making within ICSs: ‘systems’ (covering populations of 1–3 million – where agencies agree overall objectives and set strategic direction); ‘places’ (covering populations of around 250,000–500,000 people – where health and care providers work together to redesign local services); and ‘neighbourhoods’ (covering populations of around 30,000–50,000 people – where groups of GPs work with other community services in multidisciplinary teams). It also introduced an ICS ‘maturity matrix’, outlining the capabilities that local systems would need to develop to ‘mature’ and ‘thrive’, such as strong clinical leadership and the successful development of new models of integrated care.

NHS England pushed back the deadline for submitting 5-year plans from November 2019 to 2020. In September 2019, NHS England also published more detailed proposals to government for a set of ‘targeted’ changes to NHS legislation to support the development of ICSs.

Impact of the pandemic

The pandemic brought initial delays to the development of ICSs. Much local planning related to ICSs and the long term plan was paused, along with planned CCG mergers after April 2020.

But by August 2020, NHS England expected ICSs and STPs to play a central role in restoring elective care, asking them to develop new local plans for recovering services. NHS leaders reported that the pandemic had enhanced local partnership working.,, And the then health secretary, Matt Hancock, stated in early 2021 that ‘collaboration across health and social care has accelerated at a blistering pace’ during the pandemic. Assessments of local collaboration by the CQC, however, found a much more mixed picture. Collaboration was often effective where there were good pre-existing relationships and clear governance. But the CQC found confusion and duplication in areas where these were lacking. It also reported concerns that social care providers were not sufficiently involved in system working – and some felt ‘overwhelmed and isolated’.

NHS England continued to announce new ICSs during 2020, with the final 13 STP areas becoming ICSs in March 2021 (with 42 ICSs in total). This meant that the long term plan milestone of ‘full coverage’ of ICSs by April 2021 was met, – though in practice the difference between ICSs and STPs is often hard to discern. There is limited publicly available information on the composition and plans of the new ICSs.

There has also been progress towards ‘streamlined commissioning’, with mergers in 2020 and 2021 reducing the total number of CCGs to 106 (as of April 2021). This means that the majority of ICS areas are operating with a single NHS commissioner, though just over a third still have more than one in their geographical area – including Greater Manchester (10 CCGs) and South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw (five CCGs), both among the first round of ICSs announced in 2017.

The pandemic did not halt progress on developing legislation to more formally develop ICSs. Government published a white paper on NHS reform in February 2021, and a Health and Care Bill in July 2021., Under the plans, ICSs will be formally established as a new regional tier of the NHS in England. Each system will be made up of two new bodies: an integrated care board – area-based NHS agencies responsible for controlling most NHS resources to improve health and care for their local population – and an integrated care partnership – looser collaborations between the NHS, local government, and other agencies, responsible for developing an integrated care plan to guide local decisions. CCGs will be abolished and replaced by the new integrated care boards. Requirements to competitively tender clinical services will be scrapped. These changes go beyond the more pragmatic legislative changes proposed by NHS England before the pandemic. National NHS bodies and government would like the new system in place by April 2022.

Same day emergency care (SDEC)

Summary

- The long term plan committed to increase the percentage of people discharged from hospital on the same day after being admitted in an emergency from a fifth to a third. This was to be achieved by establishing specialist units to deliver ‘same day emergency care’ (SDEC) in every major emergency department, open 7 days a week by 2019/20.

- NHS England reports that in April 2021, 37% of emergency admissions were discharged on the same day, but it is not clear whether these patients have been treated in SDEC units.

- The pandemic brought disruption to emergency departments, as infection control and staff shortages limited the number of patients that could be seen safely. In early 2020, there were steep falls in emergency attendances, but pressures have rebounded as demand for emergency care has returned.

The long term plan made a number of commitments to reduce the growing pressures on emergency hospital services. For several years, A&E attendances and emergency admissions to hospital had been steadily increasing, with admissions growing by an average of 1.9% per year between 2000/01 and 2017/18. Delays admitting patients due to a lack of available beds had also increased, especially during winter, leading to overcrowding in hospital emergency departments. However, the likelihood of a patient being admitted to hospital via major emergency departments had been falling, despite a steady increase in the acuity and complexity of patient needs. This was due, at least partly, to advances in diagnostic and treatment practices that allow patients to be treated and discharged without needing an overnight stay in hospital.

SDEC – also known as Ambulatory Emergency Care – is a set of care processes whereby patients referred or self-presenting to hospital in an emergency can be assessed, receive clinically appropriate treatment and go home the same day, for conditions such as pulmonary embolisms, anaemia and urinary tract infections. Analysis of hospital data from 2018/19 suggested that although these conditions represented a small proportion of emergency admissions (3%), SDEC could avoid overnight hospital stays, improving patient experience.

The long term plan committed that every acute trust with a major A&E department would implement a comprehensive model of SDEC, operating for at least 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, by the end of 2019/20. The national rollout of SDEC was expected to increase the proportion of acute admissions discharged on the day of attendance from a fifth to a third. A related commitment was made to record 100% of patient activity on the new Emergency Care Dataset by March 2020, to monitor the use of SDEC as distinct from non-SDEC zero day stays.

Progress prior to the pandemic

NHS England reported in March 2020 that a large majority (92%) of acute trusts with a major A&E department had implemented SDEC in line with the commitment in the long term plan.

However, the reality behind these figures was likely more complex. An audit of 141 same day emergency care units, conducted by the Society of Acute Medicine (SAM), found that 45% were used as extra bed areas at times of high demand, as hospitals grappled with winter pressures in 2019/20. An inquiry into the care of patients with pulmonary embolisms – one of the conditions suitable for treatment in same day emergency care units – found that although 93% of hospitals offered a same-day service, 35% were only open on weekdays.

Impact of the pandemic

The SAM reported in June 2020 that many of the staff typically working in SDEC across hospitals had been redeployed to help with COVID-19 patients in intensive care, but at the same time a lot of ‘SDEC activity has been displaced or is not presenting at all’. Nevertheless, the SAM was concerned about the challenges of restarting SDEC with COVID-19 in circulation, which would require additional space and staff to do so safely. Pressure on emergency departments fell sharply in the early stages of the pandemic but has since increased to above pre-pandemic levels. NHS England reported that in May 2021, over 2 million patients were seen in emergency departments, double the level in May 2020, and 11% higher than April 2021.

The percentage of relevant trusts that have fully implemented SDEC has not been mentioned in NHS England board reports since March 2020. But NHS England has started to publish data on length of stay for patients following non-elective and emergency admissions. This analysis is drawn from the Secondary Uses Service and Emergency Care Data Set, breaks down admissions by zero day and 1+ day lengths of stay, and shows the number of zero day stays as a percentage of all non-elective and emergency admissions. This is published alongside the monthly A&E activity and performance statistics (though these data lag by a month). In April 2021, 37.2% of emergency admissions and 36.0% of non-elective admissions were zero day stays, broadly in line with the long term plan ambition for a third of patients to be discharged on the same day. However, it is not clear from these data whether all patients admitted and discharged on the same day actually benefited from using an SDEC service.

The Department for Health and Social Care announced an additional £150m in capital funding to upgrade A&E departments in September 2020. NHS England has committed to the expansion of SDEC services in its planning guidance for 2021/22, and to avoid unnecessary hospital admissions by maximising utilisation of SDEC. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has welcomed this pledge, but in a briefing for MPs in April 2021 reminded policymakers that, ‘The value of SDEC is not being realised as provision is patchy and highly variable across England.’

2 More action on prevention and reducing inequalities

Inequalities

Summary

- The long term plan promised a new metric for assessing local progress in reducing inequalities, but this has not been developed.

- ICSs are intended to be the main vehicle for identifying and reducing health inequalities, but local plans to reduce inequalities were not published before the pandemic began. National measures of inequalities, including gaps in life expectancy, showed that the gaps between the most and least deprived areas of the country were widening or static before COVID-19.

- Death and illness from COVID-19 have been unequally distributed, reflecting underlying health inequalities by socioeconomic and ethnic group. Multiple initiatives have been launched by NHS England to tackle inequalities in the wake of the pandemic.

The plan committed the NHS to stronger action on the prevention of ill health and promised a ‘more concerted and systematic approach to reducing health inequalities and addressing unwarranted variation in care’. Additional funding was be targeted at areas with higher health inequalities from 2019/20 to 2023/24, with local systems to develop 5 and 10-year plans to address health inequalities in their local areas. To support these plans, NHS England promised it would set out ‘measurable goals for narrowing inequalities’. Specific commitments were also made on improving access to health services for people with severe mental illness, learning disabilities or autism, better maternity services for the most vulnerable women, and specialist mental health support for people affected by homelessness.

Progress prior to the pandemic

Progress on planning commitments related to inequalities before the pandemic was slow. The Long Term Plan Implementation Framework emphasised that progress would depend on local systems (STPs and ICSs) producing plans for reducing health inequalities in their area, and the creation of more specific goals in a forthcoming green paper on prevention. Guidance on developing the plans was published alongside the implementation framework, but details of the national inequalities metrics were not, and the deadline for submitting plans was subsequently pushed back from November 2019 to 2020. While several local areas published a version of their plans before the deadline, it was (and remains) unclear what action to reduce health inequalities was being planned nationally prior to the pandemic. The green paper published in July 2019, Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s, again promised that, ‘The NHS will set out specific, measurable goals for narrowing inequalities, including those relating to poverty, through the service improvements set out in the plan.’

Official national measures of inequalities suggest that differences between the health outcomes of people living in the least and most deprived areas were static or widening before the pandemic. The annual report of the Department of Health and Social Care, published in January 2021, covering the period ending 31 March 2020, reported a widening of inequalities in 6 out of 11 overarching indicators drawn from the NHS and public health outcomes frameworks.

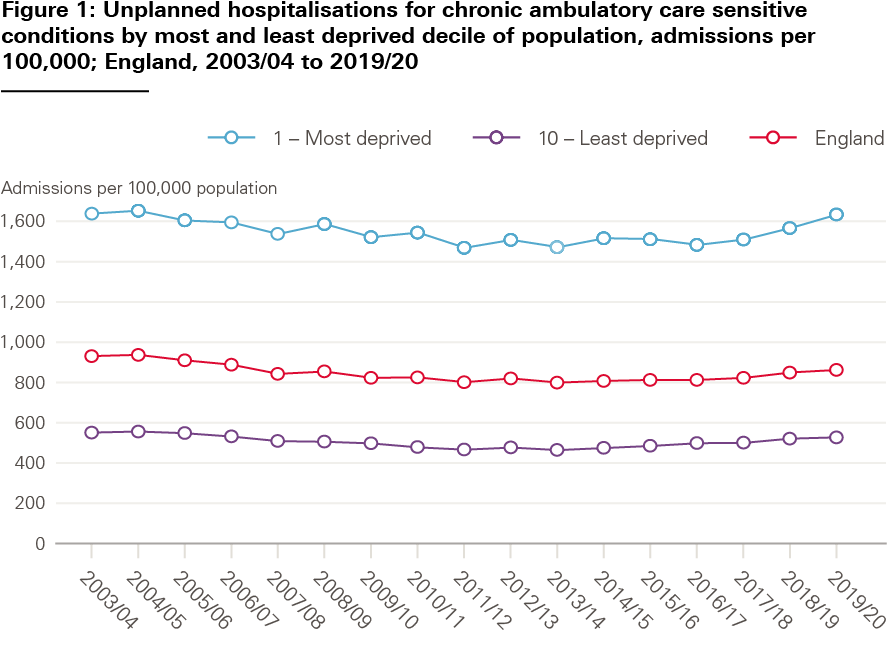

For example, the gap has widened in the rate of unplanned hospitalisation for conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure. Data produced for the CCG Improvement and Assessment Framework show that rates of unplanned admissions for these conditions decreased from 2003/04 until 2013/14, after which they started to increase (Figure 1). While the trend was the same across all deprivation deciles, rates of unplanned hospitalisations were consistently around triple in the most deprived decile compared to the least deprived (with 1,634.8 unplanned hospitalisations per 100,000 in the most deprived decile and 527.3 in the least deprived decile in 2019/20).

Other indicators where there had been a statistically significant widening of inequalities since the baseline were life expectancy at birth (for men and women), life expectancy at 75 years (for men and women) and emergency admissions for acute conditions that should not usually require hospital admission. There was no reduction of inequalities in mortality rates for those younger than 75 from cardiovascular disease, infant mortality or healthy life expectancy, all of which had been broadly stable. The only indicator where inequalities had narrowed since the baseline year or period was cancer mortality rates for those younger than 75.

Independent analyses have confirmed some of these trends. Research by QualityWatch found widening inequalities in the decade prior to the long term plan between the most and least deprived parts of England, for example in A&E waiting times and rates of hip replacements. Separate analysis by the Strategy Unit found socioeconomic inequalities in access to elective care services had widened in the years before the pandemic, even after adjusting for differences in need.

Impact of the pandemic

As the pandemic unfolded, so did evidence of the unequal harm it inflicted. Inequalities emerged not just in terms of the risk of serious illness and death, but also the risk of unemployment, capacity to work at home, self-isolate and confidence to be vaccinated. This has reignited a debate about the importance of tackling health inequalities.

In May 2020, the ONS reported a disproportionately high death rate from COVID-19 in the most deprived areas, in excess of the normal differences between areas. In August 2020, Public Health England summarised the emerging evidence on disparities in risks and outcomes of COVID-19, finding a higher risk of death for those from ethnic minority than white backgrounds, and for those working in face-to-face roles, such as caring professions. Subsequent analysis showed how pre-existing inequalities in social and economic conditions contributed to the high and unequal death toll.

In response to this growing body of evidence, in August 2020 NHS England set out eight ‘urgent actions’ to address health inequalities within the NHS as part of the pandemic recovery. ICSs and STPs, working in partnership with local communities and partners, were urged to oversee an ‘increase in the scale and pace of progress in reducing inequalities’ and to ensure regular assessment of progress. This included directions to: make digital forms of care more inclusive, accelerate prevention for those at greatest risk of poor health; support those with mental ill health; strengthen leadership and accountability; and improve the completeness and timeliness of data collection – including on ethnicity – to underpin the response to inequalities.

In June 2020, the Prime Minister instructed the Government Equalities Office and Race Disparity Unit to lead cross-government work on the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on ethnic minority groups and to publish quarterly progress reports. The second quarterly report, published in February 2021, said ‘significant progress has continued to be made’ against the eight actions outlined to NHS leaders, and ‘the majority of NHS organisations’ had appointed executive leads for health inequalities. Research by the Nuffield Trust and NHS Race and Health Observatory, published in June 2021, highlighted significant problems with ethnicity coding in NHS datasets and called for NHS England to develop new guidance.

All NHS organisations were expected to improve data collection and monitoring in relation to inequalities by 31 December 2020, while ICSs and STPs were required to submit an update on delivery of the eight urgent actions by 31 March 2021. However, information is not publicly available on whether these actions were completed. The 2021/22 planning guidance asks ICSs to prioritise early action in five areas, drawn from the eight urgent actions, alongside system-level priorities to reflect local circumstances. The five areas are: restoring NHS services inclusively; mitigating against digital exclusion; ensuring data are complete and timely; accelerating health prevention programmes for those at greatest risk; and strengthening system leadership and accountability. The guidance also makes ‘addressing health inequalities’ one of five gateway criteria for accessing additional funding for the elective backlog.

Prevention: alcohol, smoking and obesity

Summary

- The long term plan was clear that the NHS alone could not prevent ill health and that wider action from national and local government was needed.

- Three areas where the NHS could target action were included as ‘headline metrics’: setting up alcohol care teams in hospitals with the highest rate of alcohol dependence-related admissions; reducing obesity by increasing the number of people supported through the diabetes prevention programme; and offering smoking cessation services to all smokers admitted to hospital.

- Data are not available to assess progress towards the alcohol and smoking goals. Evidence suggests an increase in alcohol-related harm during the pandemic, which also disrupted wider NHS smoking cessation services.

- The diabetes prevention programme has continued to increase the numbers accessing its services, which were moved to virtual formats to reduce infection risk.

The long term plan set out a range of actions to prevent ill health, including reducing air pollution and antimicrobial resistance. It also aimed to make more of people’s contacts with the NHS to promote targeted action on smoking, alcohol and obesity, to complement the wider work on health prevention led by national and local government. The plan emphasised a 5-year funding commitment would be needed for the public health grant to local government in the next Spending Review, noting that the level of the grant ‘directly affects demand for NHS services’.

On smoking, the plan committed to a new smoke-free pregnancy pathway for expectant mothers and their partners and the offer of tobacco treatment services for all people admitted to hospital who smoke by 2023/24. A new smoking cessation offer for people using specialist mental health and learning disability services was also promised, including the option to switch to e-cigarettes.

On alcohol, specialist ‘alcohol care teams’ would be established in up to 50 hospitals with the highest rate of alcohol dependence-related admissions, with the aim of preventing up to 50,000 alcohol-related hospital admissions over 5 years.

On obesity, the plan committed to doubling the number of people offered support from or accessing support through the diabetes prevention programme. This programme identifies people at high risk of developing diabetes and offers help with maintaining a healthy weight and increasing exercise to prevent or delay onset of the disease. The plan also promised to increase access to weight management services in primary care, although no target was set for this.

Progress prior to the pandemic

The new hospital-based tobacco treatment services were due to be adopted by pilot sites in 2020/21, before being expanded nationally. The headline measure was for an increase in the percentage of people admitted to hospital offered NHS-funded tobacco treatment services, but data on this measure have not been published.

The percentage of hospitals with the highest rate of alcohol dependence-related admissions that have alcohol care teams (ACTs) in place is not publicly available. An assessment, published in 2019, found that while there has been a major increase in the number of ACTs in UK hospitals since 2010, many are ‘not resourced to provide an optimal 7-day service’. Evidence submitted as part of the recent Commission on Alcohol Harm also underlines that most hospitals are unable to provide a 7-day service and highlights that 17% of hospitals do not have a single alcohol specialist nurse.

The number of people offered support via the diabetes prevention programme increased by 38% following publication of the long term plan. 687,730 people were offered support from January to September 2020, up from 497,125 in the same months in 2019. However, there has been considerable variation between areas – the percentage of eligible patients offered support through their CCG in the same period ranged from 1% to 86%, with the highest rates in Westminster and the lowest in Bolton. Not all offers of support via the diabetes prevention programme translate into support being accessed; of those offered access to the programme in 2020, 36% declined compared with 37% in 2019.

Impact of the pandemic

The need to limit face-to-face contacts and redeploy staff during the pandemic has set back the implementation some of the prevention commitments made in the plan. In March 2020, the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training recommended that stop smoking service providers in the NHS and in the community immediately cease all face-to-face advice and carbon monoxide monitoring. Findings from an annual survey of local authority tobacco control leads, published in early 2021, suggested capacity within smoking cessation services fell in many areas, as did referrals from NHS providers to specialist stop smoking services, particularly those from secondary and maternity care. Activity to improve alcohol treatment services was suspended in April 2020, with funding for the first round of early implementor ACT sites also pushed back to October 2020. By contrast, the diabetes prevention programme continued to expand despite the pandemic, replacing face-to-face meetings with virtual meetings.

A review of alcohol consumption and harm during the pandemic by Public Health England found that the pandemic had accelerated existing trends of increasing alcohol-related hospital admissions and deaths. Emergency admissions for alcoholic liver disease increased by 13% between 2019 and 2020, and total alcohol-specific deaths were 20% higher in 2020 than 2019.

At the same time, greater awareness of the risk factors for COVID-19 may have helped to generate interest in and commitment for action to improve health. The percentage of smokers who reported that they had tried to stop smoking over the past year increased from 29.1% in 2019 to 36% between January and May 2021, and the success rate for those who tried increased from 14.2% to 26.3%.

After Public Health England reported the risk of death from COVID-19 increased by 90% in people with a BMI over 40, the government’s obesity strategy published in July 2020 committed to a further expansion of NHS weight management services beyond the commitment in the long term plan. The strategy also committed to accelerating the expansion of the diabetes prevention programme so ‘tens of thousands more people will be able to access these services than was originally included in the long term plan’.

Prevention: increase uptake of screening and immunisation

Summary

- The plan’s headline metrics promised to increase the coverage of the three main screening programmes for cancer (breast, bowel and cervical) and immunisation for MMR in children

- The pandemic brought major disruption to screening programmes, which have now resumed. Childhood immunisation rates have also fallen.

A number of commitments to increase uptake of screening and immunisation were outlined in the plan. Headline metrics focused on improving coverage of bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening and increasing MMR vaccination uptake for children younger than 5. Modernisation of the bowel cancer screening programme (through use of faecal immunochemical testing) was promised ‘to detect more cancers, earlier’, and a target set for implementing HPV primary screening for cervical cancer across England by 2020. The plan also promised to take forward findings from the independent review of cancer screening programmes led by Sir Mike Richards. Improvements in childhood immunisation were also highlighted as a priority, with an objective ‘to reach at least the base level standards in the NHS public health function agreement’.

Progress prior to the pandemic

The final report of the independent review of adult screening programmes was published in October 2019. It concluded that while each screening programme was broadly achieving its intended goal of reducing mortality, there is ‘a sense that we are now slipping’ and that each of the programmes ‘could undoubtedly do better’. The review noted that while there were signs of improvement, uptake for bowel cancer screening was the lowest out of all screening programmes and failed to meet its standard target in 2017/18. It also highlighted a slow decline in the number of people taking up screening out of those eligible for breast and cervical screening. The review concluded with a call for ‘urgent change to ensure screening programmes can be readied and resourced to maximise the opportunities they bring’.

Progress since and impact of the pandemic

Prior to the pandemic, the coverage of the bowel cancer screening programme – the proportion of the eligible population screened for bowel cancer within a given time period – was improving. However, uptake – the proportion of people invited to bowel cancer screening who were screened – had started to fall after improving from 2017 to mid-2019. During the early phase of the pandemic, the bowel cancer screening programme was paused and the main diagnostic tests limited to emergency settings.

The number of people invited to bowel cancer screening fell dramatically during the early stages of the pandemic, with only 604 people invited for screening from April to June 2020, compared with over a million in the same period in 2019. This increased to 741,406 people from July to September 2020 (still 38% lower than the same months in 2019), but towards the end of 2020 screening services began to recover lost ground, screening over 300,000 more people between October and December 2020 than in the same period in 2019.

Rates of colonoscopy (a test to look inside the bowel) have fallen, with 46% fewer people receiving colonoscopies between April and October 2020 compared with the same months in 2019. One study found that over 3,500 fewer people in England were diagnosed and treated for colorectal cancer from April to October 2020 than would have been expected. Cancer charities remained concerned about the number of people waiting for bowel cancer investigations in 2021, which, by May 2021, was five times higher than pre-pandemic.

The coverage of the breast cancer screening programme had started to fall in mid-2019 after a period of stability from 2017, and fewer people had taken up invitations to attend breast cancer screening. Official performance indicators for the breast cancer screening programme have not been published for the period covering the pandemic. 65.8% of eligible women were screened for breast cancer from October to December 2019, which fell to 55.1% from January to March 2020 – a period that overlaps with the initial stage of the pandemic. Although the breast screening programme restarted in mid-2020, the charity Breast Cancer Now reported in January 2021 that services were operating at 60% of their pre-pandemic capacity and estimated that over a million fewer women in England were screened in 2020 as a result of COVID-19.

Prior to the pandemic, coverage of the cervical cancer screening programme had been fairly stable but uptake had been falling until improvements started in 2019. Cervical cancer data are reported based on the percentage of eligible women screened in the previous 3.5 years. Therefore the full impact of the pandemic is not yet clear, but data to the end of 2020 show a clear reduction in the percentage of eligible women screened in the previous 3.5 years, from 68.1% of women aged 25–49 and 75% of women aged 50–64 screened from October to December 2020, compared with 70.7% and 76.4% in 2019.

Overall, provisional data indicate that early pauses to cancer screening as a result of the pandemic have had an impact. Cancer Research UK estimated that 3 million fewer people were screened between March and September 2020, and that the number of people beginning treatment for cancer following a referral from cancer screening was down by 42% in England from April 2020 to March 2021, compared with the same period a year earlier. It also notes that numbers of people being screened has recovered ‘fairly steadily’ since July 2020, with the number of people starting treatment after diagnosis through screening 3% higher in March 2021 compared with March 2020, with ‘no sign of a backlog coming through yet’.

The most recent childhood monthly vaccination coverage statistics point towards a ‘sustained decrease’ in children receiving routine childhood immunisations in 2020 – including for MMR – compared with 2019. Public Health England’s assessment of MMR1 (first dose) coverage measured at 18 months of age is described as falling ‘far short of the WHO target of 95% coverage by 24 months of age’. Coverage measured at 18 months of age remained around 1 to 2% lower than the 2019 estimates, since the initiation of social distancing. Public Health England’s analysis notes that the initial decrease in vaccination ‘may be associated with COVID-19 messaging about staying home initially, overwhelming the messaging that the routine immunisation programme was to remain operating as usual’. It also highlights anecdotal information that some GPs had to reschedule appointments in the initial weeks to ensure social distancing within GP practices.

3 Further progress on care quality, access and outcomes

In contrast to the previous NHS national plan (the Five year forward view), the long term plan gave much more prominence to a broader set of conditions and population groups, including targets for respiratory conditions and cardiovascular care. The headline metrics in the implementation framework were more limited in scope, however, covering childbirth, mental health, cancer, care for people with learning disabilities and waiting times.

Maternal and children’s health

Summary

- While the plan contained a number of initiatives to improve maternal and children’s health, the headline goal focused on improvements in the outcomes of maternity care. The target was for a ‘50% reduction in stillbirth, neonatal and maternal deaths and brain injury by 2025’.

- Lags in data prevent assessment of progress following the interventions begun after the long term plan was published. The most recent data (to 2019) suggest a 25% reduction in the rate of stillbirths. Neonatal deaths in babies over 24 weeks gestation have also fallen, at a rate consistent with meeting the 2025 target.

- There has been less progress in reducing brain injuries and maternal deaths, which are not on track to meet the target.

- Data to assess the impact of COVID-19 on these outcomes are not yet available. There were reductions in some antenatal appointments and restrictions on partners attending appointments and births, and disrupted services are likely to have contributed to the deaths of a small number of pregnant women.

For maternity services, the plan brought forward an existing goal of halving the rates of stillbirths, neonatal and maternal deaths and brain injury by 2030 to 2025. The target was set in 2015 (against a baseline of 2010) and much of the actions needed to achieve it began in 2016, in response to failings in maternity care identified at Morecambe Bay. Progress to reduce maternal and baby deaths was to be achieved by the adoption of consistent practices (known as the Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle); expanding continuity of care schemes so that ‘most women’ would receive ‘continuity of carer’ before, during and after birth by March 2021, with an initial focus on women most at risk of poor outcomes; and all trusts becoming part of a National Safety Collaborative (a programme to improve the quality and safety of maternity and neonatal units).

Progress prior to the pandemic

According to the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England in 2021, every trust ‘is actively implementing’ the latest version of the Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle aimed at reducing pre-term birth (including through smoking cessation for pregnant women and active fetal monitoring during birth) and the National Safety Collaborative is in place everywhere.

It is too early to assess whether the plan’s actions have improved outcomes. NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care believe that there is ‘clear progress’ towards the ambition of halving deaths in mothers and babies, while data from 2019 suggest that still births have reduced by 25% since 2010 and are ahead of the target rate of reduction. According to the National Clinical Director of Maternity and Women’s Health, the picture is more complicated for neonatal mortality rates, where the data suggested ‘we had not made much progress’. This is because recording practice has changed, with more neonatal deaths recorded in babies born at under 24 weeks gestation that would have been classified as miscarriages before 2010. When only deaths in babies over 24 weeks are counted, the neonatal mortality rate decreased by 10% between 2013 and 2017. The overall rate of brain injuries during or soon after birth ‘shows no trend downwards’ between 2010 and 2017, while the 3-year average of maternal deaths has reduced by 14% between 2010 and 2015–17.

The Health Committee gave a less positive assessment, concluding that brain injuries ‘required improvement’, while the status of progress on maternal deaths was graded ‘inadequate’.

Since the long term plan was published, the safety of maternity services has been under intense scrutiny in the wake of evidence of serious failings dating back over a decade in two NHS trusts – Shrewsbury and Telford, and East Kent. An independent inquiry into Shrewsbury and Telford issued its first report in December 2020, and the investigation into East Kent began in early 2021. NHS England issued a list of 12 ‘immediate and essential actions’ for trusts to take in December 2020 and released details of funding for additional workforce and training in March 2021.

Impact of the pandemic

Maternity services continued during the pandemic, but services were adapted to minimise the risk of COVID-19 infection. This included reductions in antenatal appointments during the first wave of the pandemic and restrictions on partners attending appointments, scans and labour., In December 2020, NHS England advised that NHS trusts ‘should find creative solutions’ to allow women to have someone with them during maternity care and birth while minimising the risk of infection.

A rapid review of 10 COVID-positive maternal deaths during the first 3 months of the pandemic concluded that pregnant women were not at higher risk of severe COVID-19, but pointed to inadequate care contributing to their deaths. A subsequent study of the deaths of 17 more women between June 2020 and March 2021 also highlighted failures in care (including inadequate remote consultations which missed complications), and noted that women ‘are fearful of seeking care’. In both reviews, the majority of cases reviewed involved women from ethnic minority backgrounds, and the increased risk of poor outcomes among this group has now become a much more prominent focus of efforts to improve maternity services. Government introduced a new target for NHS England in its 2021/22 mandate, namely ‘year on year reductions in the difference in the stillbirth and neonatal mortality rate per 1,000 births between that for black, Asian and minority ethnic women and the national average’.

Overall, the Health Committee’s evaluation of the government’s commitments on maternity care concluded that COVID-19 has exacerbated, but is not solely to blame for, delays in improving care. It notes that ‘staffing shortages persist across all maternity professions’.

Improve cancer survival

Summary

- The long term plan promised improvements in cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment, which would improve survival rates for people with cancer. The measures of progress were two-fold: increases in the 1- and 5-year survival rates for cancers, and a target of 75% of cancer patients diagnosed at earlier stages of their cancer (stage 1 or 2) by 2028.

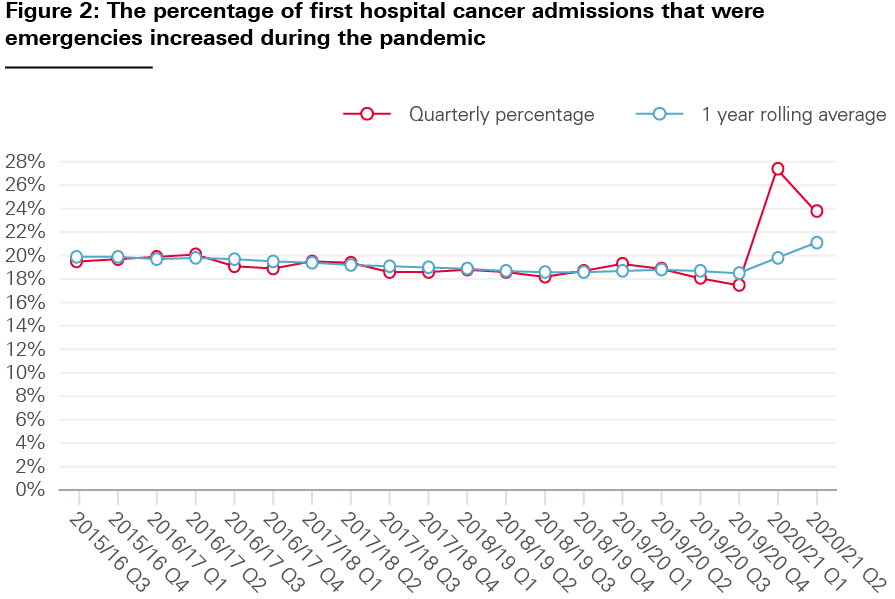

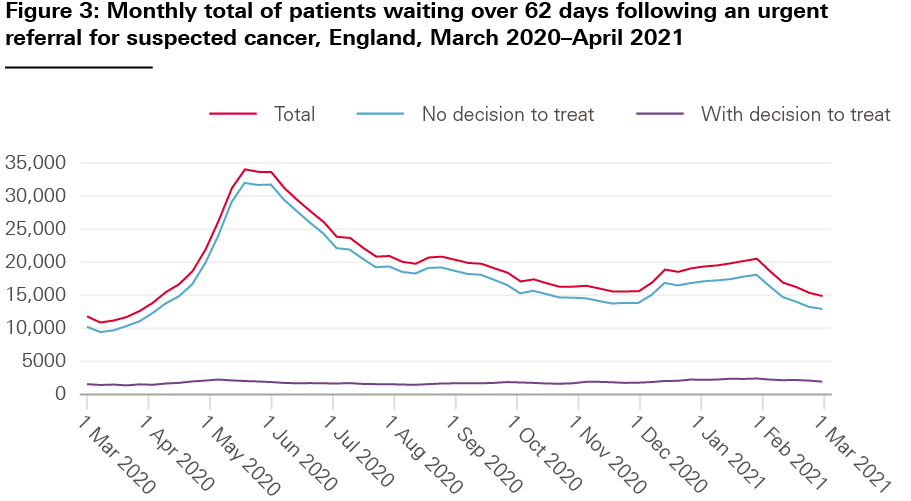

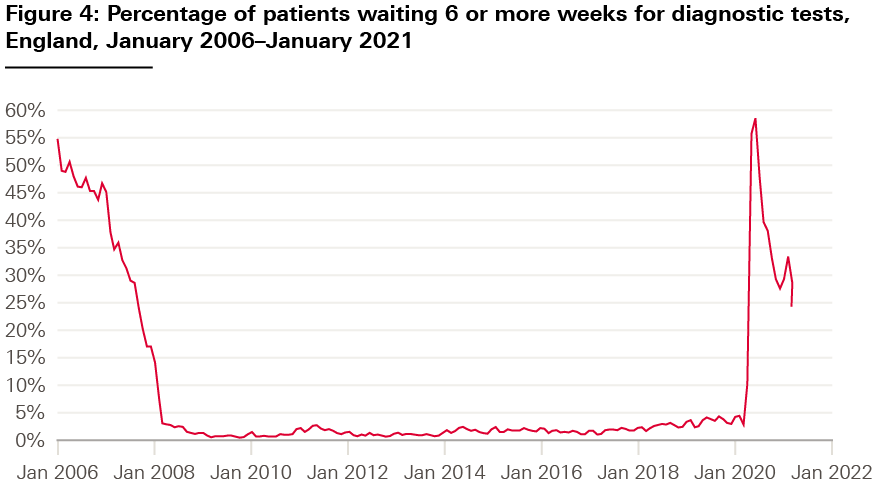

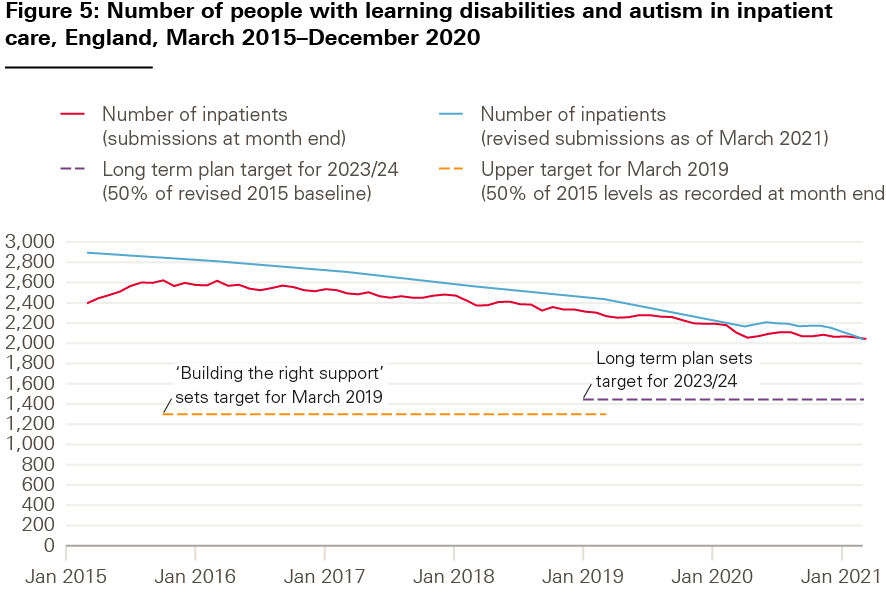

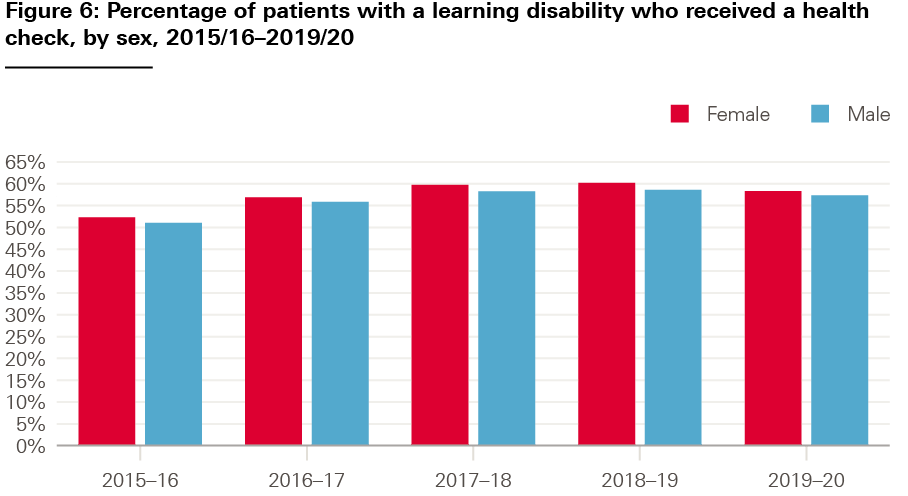

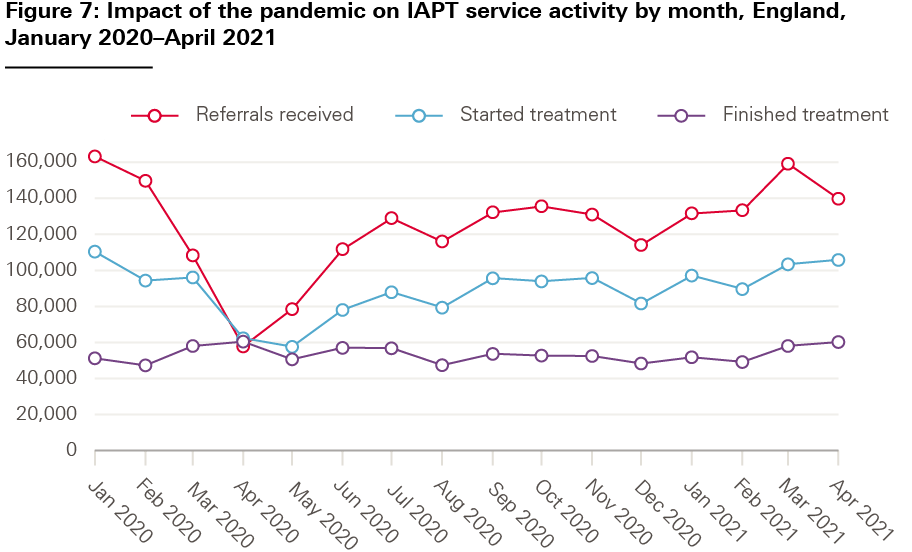

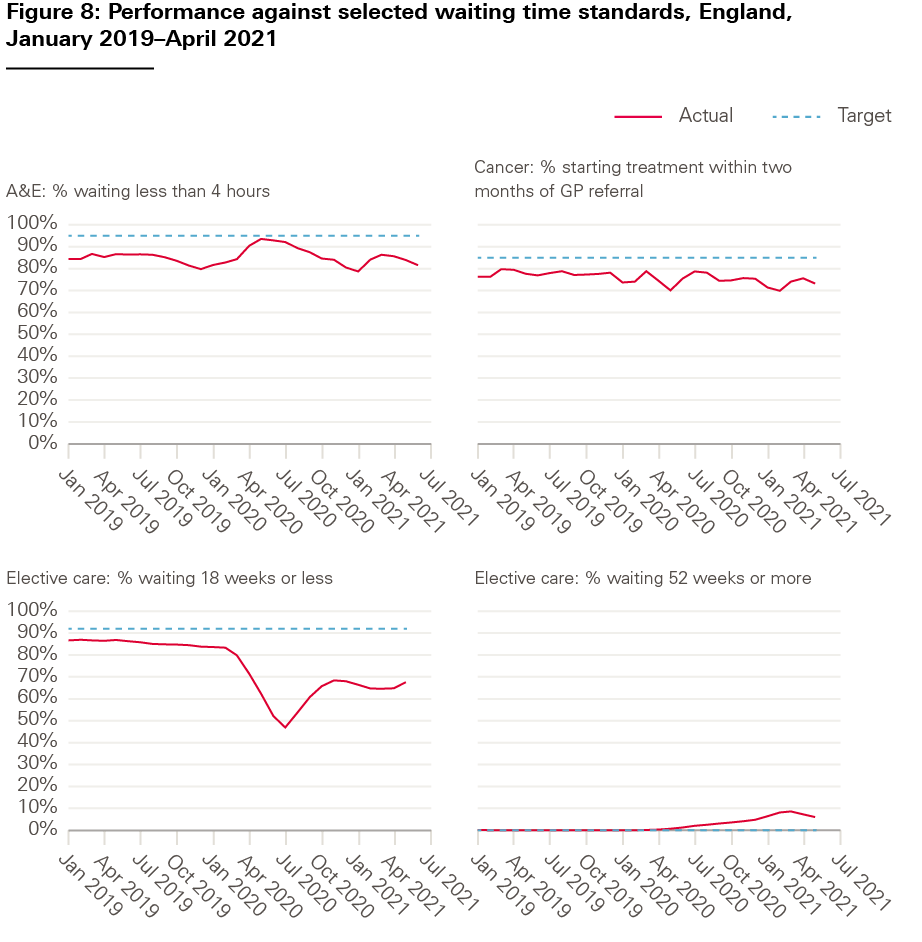

- Data for survival rates and the 75% earlier diagnosis target is not yet available beyond 2019. Before the pandemic, new rapid diagnostic hubs and bowel cancer screening techniques were being introduced.