Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a number of people who have provided helpful comments and insights during the production of this report. These include Amanda Begley, Ben Bray, Alan Davies, Jennifer Dixon, Mary Dixon Woods, Ruth Glassborow, Trish Greenhalgh, Nik Haliasos, Hugh Harvey, Kassandra Karpathakis, Josh Keith, Xiaoxuan Liu, Michael MacDonnell, Erik Mayer, Breid O’Brien, Sarah Jane Reed, Paul Sullivan, Richard Turnbull and Wenjuan Wang.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2021-I03

Key points

- As the NHS emerges from the latest wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are hopes that technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence (AI) will be able to help it recover, as well as meet the very significant future demand challenges it was already facing (and which have since grown worse). Drawing on learning from the Health Foundation’s research and programmes, along with YouGov surveys of over 4,000 UK adults and 1,000 NHS staff, this report explores the opportunities for automation and AI in health care and the challenges of deploying them in practice. We find that while these technologies hold huge potential for improving care and supporting the NHS to increase its productivity, in developing and deploying them we must be careful not to squeeze out the human dimension of health care, and must support the health and care workforce to adapt to and shape technological change.

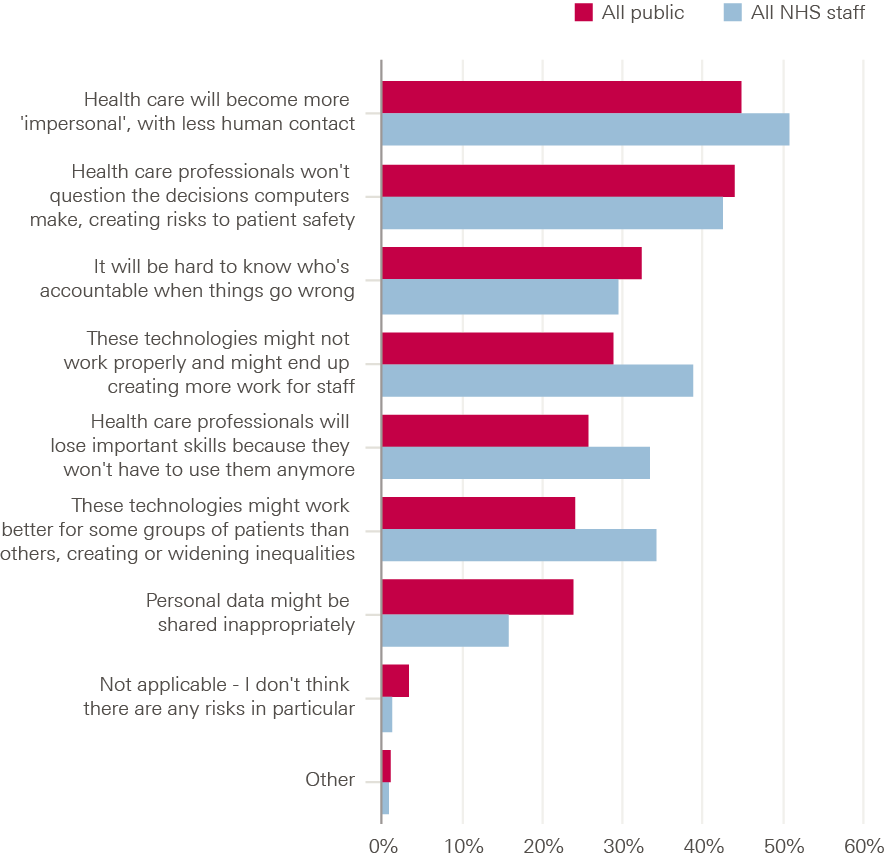

- The nature of health care constrains the use of automation and AI technologies in important ways. Health care is a service that is fundamentally co-produced between patients and clinicians, making the human, relational dimension critically important to the quality of care. The prospect of health care becoming more impersonal with less human contact was ranked the biggest risk of automation in both our public and NHS staff surveys. Furthermore, many health care tasks require skills and traits that computers cannot yet replicate, while the complexity of many tasks and work environments in health care also poses challenges for automation. Much of what is known about the use of automation is taken from product manufacturing, meaning caution is required in assessing how well ideas and strategies from the wider literature might translate into health care.

- Given the nature of work in health care is different to many other industries, the impact of these technologies on work will also tend to be different. In many cases, automation and AI technologies will be deployed to support rather than replace workers, potentially improving the quality of work rather than threatening it. Particular opportunities exist for the automation of administrative tasks, freeing up NHS staff to focus on activities where humans add most value – which is especially important at a time when the NHS is struggling with significant demand pressures and longstanding workforce shortages. In other cases, automation and AI can significantly enhance human abilities, such as with information analysis to support decision making, with the dividends accruing through combining human and machine input.

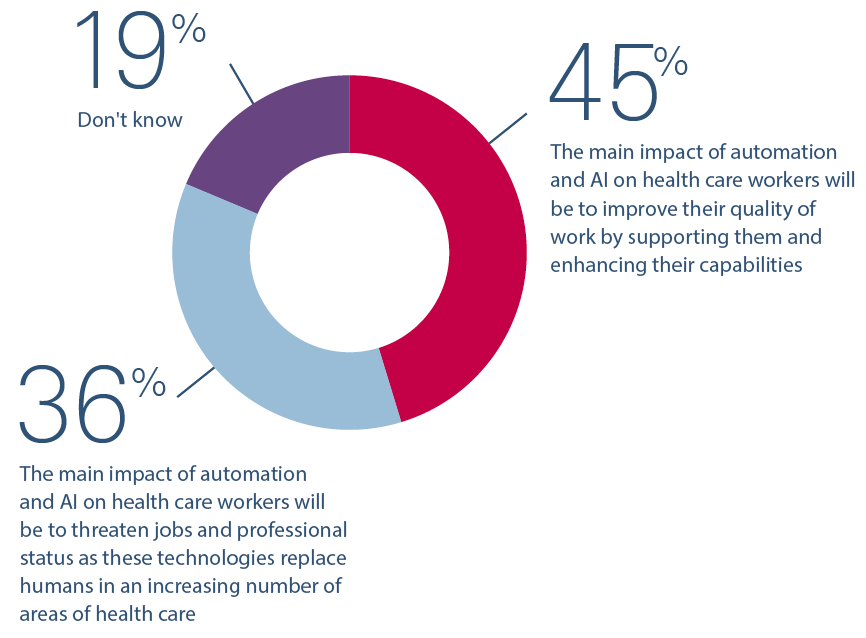

- Government and NHS leaders have an important role to play in working with and supporting health care workers to respond to the rise of automation and AI, especially those parts of the workforce that may be more heavily impacted. The NHS staff we surveyed were on balance slightly optimistic about the future impact of automation, with more thinking the main impact would be to improve the quality of work rather than to threaten jobs and professional status. Nevertheless, there were occupational differences in these views, highlighting that these technologies may have an uneven impact across the workforce.

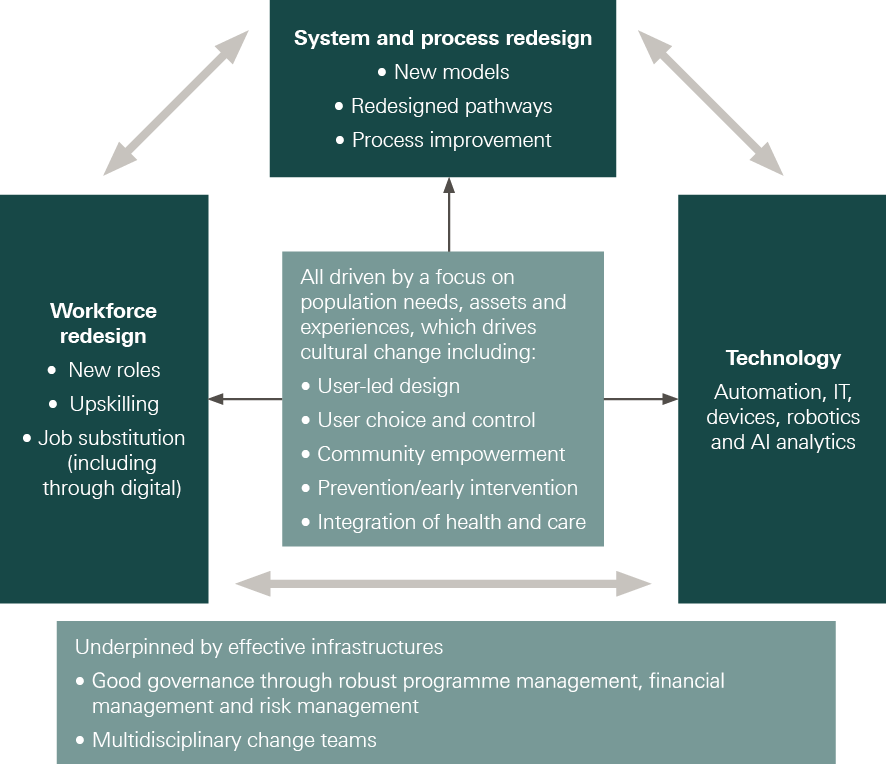

- The benefits of a new technology clearly don’t come from how it performs in isolation, but from fitting it successfully into a live health care setting and redesigning roles and ways of working to derive the benefits of the new functionalities it offers. And the journey from having a viable technology product to successful use in practice is often significant. Teams and organisations will need to consider the ‘human infrastructure’ and processes that need to accompany the technology, and policymakers, organisational leaders and system leaders will need to fund ‘the change’ not just ‘the tech’.

- Government, working with health care professions and industry, needs to engage proactively with the automation agenda to shape outcomes for the benefit of patients, health care workers and society as a whole. In particular, government and NHS leaders have an important role to play in identifying and articulating NHS needs and priorities, working proactively with researchers and industry to ensure that technologies are developed to meet important health care problems, and supporting the development and adoption of technologies in practice.

- While new, cutting-edge medical applications of automation and AI often steal the headlines, there are also important quality and efficiency gains to be made through applying these technologies to more routine, everyday tasks such as dealing with letters or appointment scheduling. There is also scope to get more out of existing applications of these technologies. So it is important for the NHS to have strategies in place for doing this, as well as supporting the development of new technologies.

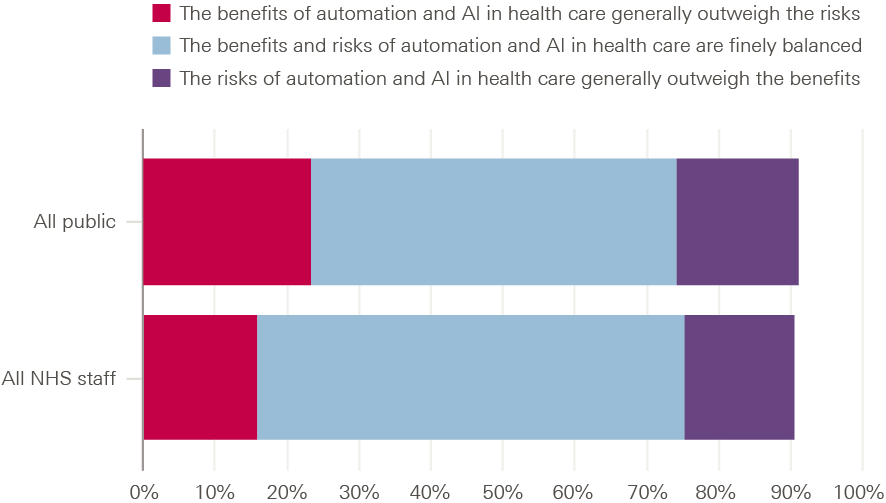

- Our surveys found public and NHS staff opinion divided on whether automation and AI in health care are a good thing or a bad thing. Majorities said the benefits and risks were finely balanced, and some groups tended to be less positive than others. So government and NHS leaders must engage with the public and NHS workforce to raise awareness and build confidence about technology-enabled care as well as to better understand views about how these technologies should and should not be applied in health care, how we can ensure they serve the needs of all groups, and how important risks should be mitigated. Notably, our surveys also found that those who had already heard about these technologies tended to be more positive about them, so helping to familiarise people with this topic could play an important role in shaping attitudes.

Introduction

This report presents the findings of Health Foundation research on the opportunities and challenges for automation and artificial intelligence (AI) in health care, alongside some of the findings of a recent research study by the University of Oxford (henceforth ‘the Oxford study’), supported by the Health Foundation, into the potential of automation in primary care in England (described further in Box 2). We explore the increasing number of areas in which automation, AI and robotic technologies are being applied to both clinical and administrative tasks, the challenges for making automation work on the front line, what automation might mean for the future of work in health care, and how the NHS can get this agenda right for the long term. As well as the Oxford study, the report draws on a wide range of other academic studies in this field, plus learning from across the Health Foundation’s programmes, fellowships, research and evaluations. This research is also supplemented by surveys of the UK public and NHS staff, to explore views about automation and AI in health care.

By sharing learning from our programmes on how to make change happen, our aim is to increase understanding among policymakers, organisation and system leaders and front-line staff of what it takes to turn promising ideas into improvements in health and care. That requires bridging the gap between policy and practice. It also requires exploring the human side of health care as well as the technical, to understand what its social and relational dimensions mean for how we should go about improving services.

Nowhere are these concerns more relevant than with health technology and automation, where too often the temptation is to focus on the technology itself rather than on how people use it or experience it. And where too often the temptation is to see the algorithm, the software or the new piece of kit as the answer, rather than as an enabler of change – one that will only help if responding to an accurate diagnosis of what is needed. It is these kinds of issues and concerns that we seek to explore in this report.

Box 1: Defining automation

Automation, at its simplest, is the use of technology to undertake tasks with minimal human input. In this report, we use the term broadly to include:

- the full automation of tasks and also the partial automation of tasks (where only certain components of a task are automated)

- technologies that operate autonomously or semi-autonomously, and also technologies that automate tasks without operating autonomously

- the use of technologies to support humans in performing tasks (for example, the automation of information analysis to assist human decision making), as well as the use of technologies to replace humans in performing tasks (for example, the automation of all stages of a decision process)

- applications of technologies such as AI and robotics that are creating new opportunities for automation.

The current context

Recent advances in computing and data analytics, coupled with the increasing availability of large datasets, are pushing the boundaries of what is possible with automation, giving rise to a host of new opportunities, from driverless vehicles to robotic carers. Many believe automation will transform the labour market – not just in sectors like manufacturing, transport and financial services, but also in health care – leading to significant changes in the nature of work and the skills needed to succeed in the future job market. In health care, these technologies also hold great potential to improve the quality of care for patients and the quality of work for staff, something that has been recognised by policymakers across the UK – in England, for example, through the NHS Long Term Plan, the Department of Health and Social Care’s Technology Vision, the creation of NHSX and the investment of £250m to create the NHS AI Lab.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also given fresh impetus to the use of technologies in health care, including technologies that could be classed as automation such as devices for monitoring health. And where they have been successful, there is hope in many quarters that the NHS will be able to build on this progress and embed these technologies as part of ‘business as usual’. There is also hope that automation, AI and robotic technologies will be one important part of the answer to coping with the unprecedented demand pressures the NHS is facing as it moves beyond the emergency phase of the pandemic, including a huge backlog of elective care – pressures that will necessitate increased productivity as well as expanded capacity. In this sense, COVID-19 has only heightened the need for the NHS to have effective strategies for these technologies and a detailed understanding of how to support their design, implementation and use.

However, while there is rightly much excitement about the potential of automation, AI and robotics, what we also see from the Health Foundation’s programmes is that deciding where these technologies should (and should not) be applied, and understanding how they can be implemented and used successfully, are challenging issues that will require careful consideration by policymakers, organisation and system leaders, and those leading change on the front line. And while it is the promise of new technologies that receives much of the policy and media focus, we believe the challenges and constraints require just as much attention.

It is precisely an awareness of these challenges and constraints that will be needed in developing effective automation strategies for the future. As the Health Foundation’s report Shaping Health Futures highlights, policymakers and system leaders need a realistic understanding of the big trends on the horizon, like automation and AI, and need to factor them into strategic decision making. This is also important for health and care professions, and the health and care workforce as a whole, which some have argued will be transformed by the current wave of technological change. It also has significance for those in industry, who will need to work closely with NHS staff and patients in developing new technologies. As automation and AI technologies continue to develop and their use in health care becomes more widespread, it is crucial we shape their impact for the benefit of staff, patients and society as a whole.

Content overview

Chapter 1 provides background on automation in health care. It briefly explores the concept of automation, its relationship to AI and robotics, and the impact it could have on the future of work. It also highlights some recent policy responses to automation and AI in the UK, and looks at public and professional attitudes to automation.

Chapter 2 considers the types of task most amenable to automation. It then explores some of the different ways in which automation and AI are being applied, or could be applied, in health care, to both clinical and administrative tasks.

Chapter 3 looks at the main constraints and challenges that will need to be understood and addressed in order to make the most of automation and AI in health care. These include the challenges of replicating human skills, the indispensability of human agency in certain aspects of health care and the complexity of many kinds of health care tasks. This chapter also explores some challenges of implementing and using automation and AI technologies effectively in practice.

Chapter 4 highlights the implications of these constraints and challenges for policymakers, organisation and system leaders, and those leading change on the front line. It reflects on how automation might affect work in health care, explores public and NHS staff views on the benefits and risks of automation in health care, and concludes with recommendations for policymakers, practitioners, organisation and system leaders (including leaders in providers, health boards, integrated care systems, and regional and national bodies) and industry.

Box 2: The Oxford automation study – The Future of Healthcare: Computerisation, Automation and General Practice Services

The high volume of administrative work in health care is well documented, and a particular challenge in general practice. This study sought to assess the potential of automation technologies currently available on the market to conduct administrative tasks in primary care. Funded by the Health Foundation, it was led by the Oxford Internet Institute, the Oxford Department of Engineering Science and the Oxford Martin School during 2017–19.

Through over 350 hours of ethnographic observation at six primary care centres in England, the researchers identified 16 unique occupations performing over 130 different tasks. Using ratings of task automatability from a survey of automation experts and combining this with data from the O*NET database (a repository of US occupational definitions that describes the skills, knowledge and abilities different kinds of task require), the team then applied a machine learning model to assess the automatability of each task – ranging from ‘not automatable today’ to ‘completely automatable today’. The results were then analysed to produce insights about the nature of work in primary care, and about where automation is most likely and where it could be most useful.

The findings of the research, published in BMJ Open and by the University of Oxford, show that:

- 44% of all administrative work performed in general practice can be either mostly or completely automated, such as running payroll, sorting post, transcription work and printing letters

- automating administrative tasks has the potential to free up staff to spend more time with patients, improving the quality of care and the quality of work

- while every occupation in general practice, including clinical roles, involves a significant amount of time performing administrative work, no single full-time occupation could be entirely automated.

1. A brief introduction to automation and AI

1-1 What are automation and AI?

Automation is the use of technology to perform rule-based tasks with minimal human input. Encyclopaedia Britannica describes it as ‘performing a process by means of programmed commands combined with automatic feedback control to ensure proper execution of the instructions’, while the International Society of Automation defines it specifically as ‘the creation and application of technology to monitor and control the production and delivery of products and services’. While automation typically involves the execution of tasks previously done by humans, this is not necessarily a defining feature, with increasingly sophisticated technology enabling the automatic performance of tasks humans could not do, such as rapid analysis of large datasets.

Automation is a major theme in discourse about changing labour markets and the future of work. For many tasks, automated systems have the potential to improve on human performance, by reducing errors and improving productivity, and analysis conducted in 2019 by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) found that around 1.5 million jobs in England were at high risk of having some of their duties and tasks automated in future. This report will look at both the potential automation of tasks usually undertaken by health care workers, as well as the use of automation and AI to assist health care workers in performing tasks.

Advances in robotics and AI are extending the reach and capability of automation, both in the realm of physical tasks and increasingly the realm of cognitive tasks; as the AI Index puts it, ‘robotics puts computing into motion and gives machines autonomy. AI adds intelligence, giving machines the ability to reason’. A 2016 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee report describes AI as statistical tools and algorithms that ‘enable computers to simulate elements of human behaviour such as learning, reasoning and classification’. Recent years have seen advances in AI due to the increasing availability and quality of data, and improvements in technology and processing power. These include developments in machine learning, where algorithms are trained to make predictions using large datasets, and especially in ‘deep learning’, a type of machine learning using artificial neural networks. Among other things, these systems can learn to recognise and classify patterns in digital representations of sounds, images and text.

Given the significant overlap between these fields, this report will often refer to AI and robotics alongside automation, including situations where these technologies are used to automate some parts of a task (such as information analysis for decision making) but not others (such as decision selection).

1.1.1. Modes of automation: replacing versus assisting

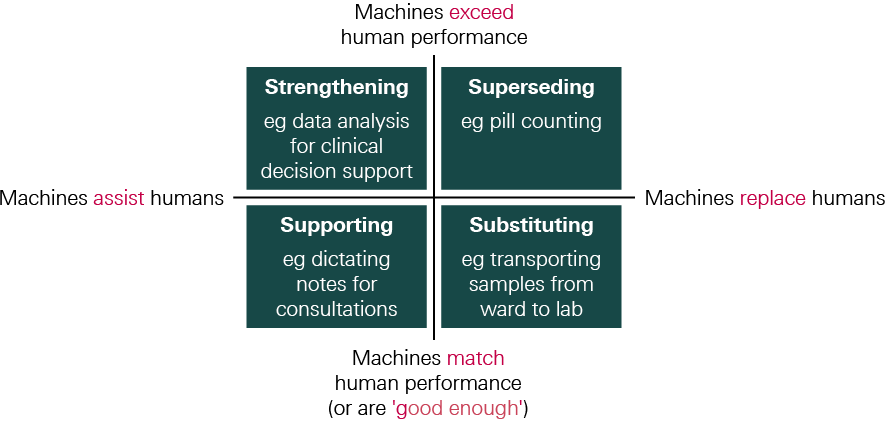

It’s useful to distinguish between some different ways in which automation can relate to human task performance in health care.

Replacing: As highlighted above, in some cases automated systems are intended to perform tasks previously carried out by humans, replacing human input.

- This can happen where an automated system is able to perform tasks to a similar level to human workers (or at least to a ‘good enough’ standard), and so using an automated system to perform these tasks can free up health care staff to focus on other work. In Figure 1, this mode of automation is described as substituting for human input.

- On other occasions, the performance of an automated system might significantly exceed human capabilities, so by replacing human input it provides an opportunity to improve task performance (for example, where an automated system can execute tasks at much greater speed), and this may provide a rationale for automation independently of the benefits of releasing staff time. In Figure 1, this mode of automation is described as superseding human input.

Assisting: More commonly, automated systems can be used in health care to assist workers, rather than replace them.

- This can happen by using technology to automate just one component of a task or to provide additional capacity or functionality in a way that allows a worker to improve task performance – not because they can’t do what the technology is doing, but simply because having the technology effectively increases their capacity and allows them to focus on other aspects of task performance (for example, using dictation software to take notes). In Figure 1, this mode of automation is described as supporting human input.

- On other occasions, technologies designed to assist human task performance may also extend human capabilities, even though they are not intended to operate autonomously. For example, surgical robots may allow a greater degree of precision than humans alone, while AI-driven clinical decision support tools may exceed human information-processing capabilities. In Figure 1, this mode of automation is described as strengthening human input. Indeed, research suggests that while AI systems can match or even exceed humans in some ‘high end’ tasks (those requiring a high level of cognitive ability), when these systems are combined with human experience, intuition and knowledge, the impact of AI and robotics can be increased.

Figure 1 illustrates these different modes of automation. Note that the same technology could be used in different ways; the mode of automation will depend on how it is deployed on any particular occasion. It is worth noting that when technologies are deployed for supporting or substituting (the bottom row), the primary motivation is often to free up staff time, whereas when technologies are deployed for strengthening or superseding (the top row), the primary motivation is often to improve task performance.

Figure 1: Modes of automation

The use of automation to assist (and enhance) rather than replace is one way in which the impact of automation in health care can differ from other sectors. In industries such as agriculture and manufacturing, new technologies have often replaced labour (for example, the combine harvester or industrial robots for painting), a trend that continues today. A 2019 report by Oxford Economics estimates that around 1.7 million manufacturing jobs have been replaced by robots since 2000, including 400,000 in Europe. In health care, by contrast, new technologies have for the most part tended to supplement rather than replace labour, providing the means for health care workers to improve care or do their job more efficiently. This is partly because, as we explore in Chapter 3, many tasks in health care are difficult to automate. Instead, it is the potential of automation to assist NHS staff to manage high workloads that has attracted interest as demand for staff continues to increase.

Box 3: A brief history of automation in health care

Automation has its roots in the Industrial Revolution when the introduction of the steam engine enabled the generation of vast amounts of energy, allowing the mechanisation of tasks previously undertaken by craftsmen or by individual artisans. Since then, innovations such as the spinning jenny, assembly line and personal computer have seen the automation of many types of work. Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that automation can be divided into two periods: the first, in which machines were introduced to conduct physical tasks (such as assembling a product), and the second enabled by the development of computing, in which machines also conduct cognitive tasks (such as record-keeping).

Automation has a long history in health care. Many examples are now so well established that we might not think of them as automation. For instance, in the early 1900s the first electrocardiogram was developed to monitor heart rate, something previously done manually. From the 1940s onwards, the kidney dialysis machine evolved to become automatically functioning. In the late 1970s, the desktop computer began to enable the automation of administrative tasks, for example clerical tasks such as financial calculations. Computers also began to be integrated into clinical pathways, initially to enter orders and report results and then to hold databases, images and patient records, as well as for the continuous monitoring of patients. Pharmacists have also seen the automation of several aspects of their work; for example, the first digital pill counter was deployed in the late 1960s.

Robots, too, have been used in medicine and health and social care for over 30 years, from robot-assisted surgery and rehabilitation, to personal robots serving as companions or motivational coaches, or assisting people with domestic activities. In surgery, robots are being used to perform movements once made by humans, though typically requiring tele-operation or supervision by a health care professional. In addition, the ongoing miniaturisation of electronics is expanding the types of procedures that surgical robots can support, although it is important to note that the evidence base for the clinical effectiveness of robots in surgery is still developing.

The potential of new data analytics and AI to support clinical decision making, such as image analysis and risk prediction tools, understandably attracts considerable excitement. At the same time, there remains vast potential for the automation of less complex tasks, including work that has administrative components such as processing prescriptions, referrals and bookings, through technologies that are currently available or are already in the NHS but not being used to their full potential. For example, the 2016 Carter Review found that trusts were not getting ‘full meaningful use’ from technologies they had invested in such as e-prescribing software.

1.1.2. Automation and the future labour market

While automation is not a new concept (see Box 3 for a brief history of automation in health care), the evolving capabilities of AI and robotics to undertake increasingly complex cognitive tasks, as well as an ever-growing range of manual tasks, have become a key consideration in analyses of how jobs and occupations could change in the coming decades.

Studies modelling the impact of automation on the future labour market have produced a wide range of estimates, but suggest the impact could be both far-reaching and unevenly distributed. For example, Frey and Osbourne estimate that 47% of occupations could be automated over the next 20 years, with roles in office and administrative support, production, transportation and service occupations highly susceptible. On the other hand, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that only 9% of occupations are at high risk of automation because many still contain a substantial share of tasks that are hard to automate. The ONS, investigating work in England, suggests that the impact of automation will vary across the labour market, with lower-skilled roles more susceptible to automation and women, young people and part-time workers most likely to work in roles that are at high risk of being automated.

Predicting the precise effects of automation on employment is difficult, however. The OECD study argues that even if a job is at high risk of automation, it will not necessarily result in job losses because workers can adapt by switching tasks and expanding their roles, and because technological change will also create new jobs. Similarly, a 2019 European Commission report argues it is unclear whether the net effect of automation will be job replacement or augmentation, given that AI and robotics will create new jobs as well as eliminate others.

Modelling also suggests the impact of automation will vary by sector. In line with the observations above that automation in health care has tended to supplement rather than replace labour, studies estimate the future impact of automation on jobs in health and care to be lower than in other sectors. For example, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) estimates the proportion of jobs at high risk of automation in health care could rise from around 3% in the early 2020s to 20% by the mid-2030s, with financial services seeing the biggest effects over the short term and the transport sector over the longer term. The PwC model suggests the impact on jobs in health and care, as well as in education, will be lower than in other sectors.

In light of these trends, policymakers are grappling with how to respond to the labour market impacts of automation. The 2016 Taylor Review, for example, explored how employment practices need to change in order to keep pace with the modern economy. Specifically in relation to automation, the Review highlighted the importance of supporting people to gain appropriate skills for the future workplace – in particular, skills that are less likely to be affected by automation, such as relationship building, empathy and negotiation, which over time could become more valuable. It also highlighted the importance of lifelong learning to enable people to adapt to, and remain relevant in, a changing labour market.

1-2 Policy approaches to support automation and AI in health care

In health and care, policymakers are also focusing on helping providers and patients exploit the potential of new technologies. In England, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and NHS England and NHS Improvement have focused on several broad challenges relating to digital technology and information technology (IT). The aim in particular has been to ensure the NHS has the right basic infrastructure in place, with systems that are interoperable and enable the exchange of data, as well as addressing challenges around leadership and skills. Key initiatives include:

- The 2016 Wachter Review of health IT in secondary care, noting that the quality of IT systems across the NHS remains patchy, interoperability continues to be a challenge and progress towards digitisation of records is slow, made a series of recommendations to achieve digitisation.

- The DHSC’s 2018 ‘vision’ for digital, data and technology in health and care aspires to harness fast-developing technologies including AI and robotics, but also acknowledges the need to ‘get the basics right’ and ensure the NHS has appropriate digital infrastructure in place. This is essential not just for basic clinical and administrative functions, but also as a platform to enable the use of more sophisticated technologies.

- In 2018, NHS England and NHS Improvement launched the Local Health and Care Record Exemplars Programme, designed to enable the safe and secure sharing of health and care information across different parts of the NHS and social care.

- The NHS Long Term Plan, published in January 2019, also committed to making better use of digital technology, including providing better digital access to services and ensuring health records and care plans are available to clinicians and patients electronically. It also restated ambitions to make greater use of AI to support clinical decision making and to put in place IT infrastructure that is secure and allows interoperability between systems.

- NHSX, a joint unit between the DHSC and NHS England and NHS Improvement, created in 2019, provides leadership for digital technology in health and social care and will play an integral role in NHS England and NHS Improvement’s transformation directorate (see Box 7 on page 30 for further information). The 2019 Topol Review looked at how to equip the health care workforce to work effectively with new technologies, to inform the development of Health Education England’s (HEE’s) workforce strategy. HEE is seeking to address the workforce requirements set out in the Topol Review through the Digital Readiness Programme.

In Scotland, the Scottish government, the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities and NHS Scotland see digital technology as a critical enabler for improving health and care. The 2018 Digital Health and Care Strategy for Scotland seeks to empower citizens to manage their own health, live independently and access services through digital means, and also to put in place the architectural and information governance ‘building blocks’ necessary for the effective flow of information across the whole care system. Digital technology is also an important part of the Welsh government’s vision for health and care. A Healthier Wales: Our Plan for Health and Social Care seeks to use digital, data and communications technologies to help raise the quality and value of health and social care services. To help embed the development and use of digital services in health and care in Wales, the Welsh government launched a new special health authority, Digital Health and Care Wales, in April 2021.

The term ‘automation’ is not especially prominent in UK health care policy discourse, perhaps because it is often taken to mean the full automation of tasks (replacing human labour), whereas many of the technologies in question are seen primarily as tools to support staff to undertake tasks rather than to wholly automate them. Where automation has been discussed, the focus has been mainly on reducing the burden of administrative work for clinical staff, and improving efficiency and productivity, on the assumption that automation can free up time for patient care., Notwithstanding this lack of prominence of automation as a theme, there has been considerable policy interest in digital and data-driven technologies that have the potential to automate tasks, including AI:

- As part of the Industrial Strategy’s ‘AI Grand Challenge’, in 2019 the UK government set an ambition of using data, AI and innovation to transform the prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of diseases like cancer, diabetes, heart disease and dementia. This included launching five new centres of excellence in digital pathology and imaging with AI.

- In 2019, NHS England and NHS Improvement set an ambition for the NHS to become a world leader in AI and machine learning within five years, inviting technology innovators to submit proposals for ‘how the NHS can harness innovative solutions that can free up staff time and cut the time patients wait for results’.

- £250m was invested in the creation of a new NHS AI Lab, that sits within NHSX and focuses on areas such as regulation, imaging, disease detection, ethics and supporting the development of AI products. As part of this, the Artificial Intelligence in Health and Care Award is making £140m available over three years to accelerate the testing and evaluation of AI technologies that support the aims of the NHS Long Term Plan. The AI Lab has also launched an ethics initiative to ensure that AI products used in the NHS and care settings do not exacerbate health inequalities, in partnership with the Health Foundation, the National Institute for Health and Research, the Ada Lovelace Institute and HEE.

- The Accelerated Access Collaborative, a partnership between government, industry and the NHS, was established in 2018 to identify promising technologies, including AI, that the NHS should prioritise for adoption.

- In 2019, the DHSC and NHS England and NHS Improvement launched a code of conduct (since updated to become the Guide to good practice for digital and data-driven health technologies) to guide the development and use of digital and data-driven technologies, designed to protect patient data and ensure only high-quality technologies are used by the NHS.

- Prior to the announcement of the new National Institute for Health Protection, Public Health England’s Strategy 2020 to 2025 had set an ambition to develop ‘personalised prevention’ of ill health and enhance the data and surveillance capabilities of the public health system using technology such as AI.

- In 2018, the UK government announced the creation of a new AI health research centre in Scotland. Based in Glasgow, the Industrial Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research in Digital Diagnostics (iCAIRD) is focused on the exploration of how AI could improve patient diagnosis.

- The Welsh government is currently supporting several AI projects, including the use of AI to detect harmful or potentially harmful incidents in real time for people affected by falls, people with dementia and people with cognitive impairments.

- In 2020, the House of Lords Liaison Committee on AI published the report AI in the UK: No Room for Complacency, which considers the UK government’s progress against the recommendations made by the Select Committee on AI in its 2018 report, AI in the UK: ready, willing and able?

- In 2021, the UK AI Council, an independent expert committee that provides advice to the UK government, published a road map to help the UK become one of the best places in the world to live with, work with and develop AI.

1-3 Public, patient and professional attitudes to automation and AI

Several themes recur in surveys exploring public views of automation and AI in health care. While access, speed and accuracy are often cited as potential benefits, many people clearly value human agency, interaction and judgement and don’t want to see them compromised or removed. For example:

- An international survey in 2016 found that, while there is some support for using AI and robotics to meet health care needs, people in the UK were more sceptical compared to other countries. For example, UK respondents were least willing to undergo ‘surgery performed by a robot’. UK respondents felt that the main advantages of AI and robotics in health care were quicker and easier access, and faster and more accurate diagnosis. However, the main disadvantages cited were inability to trust automated decision making, the belief that only humans can make the right decisions and the view that health care needs a ‘human touch’.

- A 2017 UK poll found that while many would be happy with AI playing a supportive role, there were concerns about the automation of work typically done by doctors and nurses. In particular, the poll showed that while many respondents would welcome the use of AI to help diagnose diseases, most did not think AI should be used for other tasks usually performed by doctors and nurses, such as suggesting treatment.,

- Another 2017 UK poll found that people were optimistic about the potential of the technology to improve the accuracy and speed of diagnosis and were also ‘happy with the idea of doctors and machines working together to provide a better service’. Their main concern was the prospect of human interaction being lost. For example, respondents cited the importance of human involvement in final diagnosis and treatment planning, which they felt should be reviewed, authorised and communicated by a human doctor.

Turning to the perceptions of health care professionals and managers on the prospects for, and impact of, automation, there is a mixture of optimism and scepticism. For example:

- In a 2018 US survey of radiologists exploring views about job security, respondents said that AI would make their job radically different in the next 10–20 years, but very few felt that it would make their roles obsolete., Most respondents were planning to learn about AI in relation to their jobs and a smaller majority were willing to help train an algorithm to do some of the tasks of a radiologist. In the UK, the Royal College of Radiologists has similarly taken a positive view of AI, welcoming the introduction of appropriately regulated technologies to enhance clinical practice, citing the potential to improve outcomes and efficiency, and release time for direct patient care and research.

- A 2018 survey of managers and clinicians working in NHS trusts, clinical commissioning groups and NHS England and NHS Improvement found that while senior managers showed enthusiasm about AI, clinicians were more cautious, emphasising the need for safeguards.

- There appears to be less professional caution around the prospect of automating administrative tasks compared to clinical tasks. For example, a recent UK survey of GPs showed that while the majority were sceptical about the potential for future technology to perform most primary care tasks as well as or better than humans, many were optimistic that in the near future technology would have the capacity to fully replace GPs in undertaking administrative duties related to patient documentation., The Royal College of General Practitioners has highlighted the automation of administrative tasks as one of four key areas where technology could be particularly beneficial.,

Box 4: Public and NHS staff attitudes to automation and AI in health care

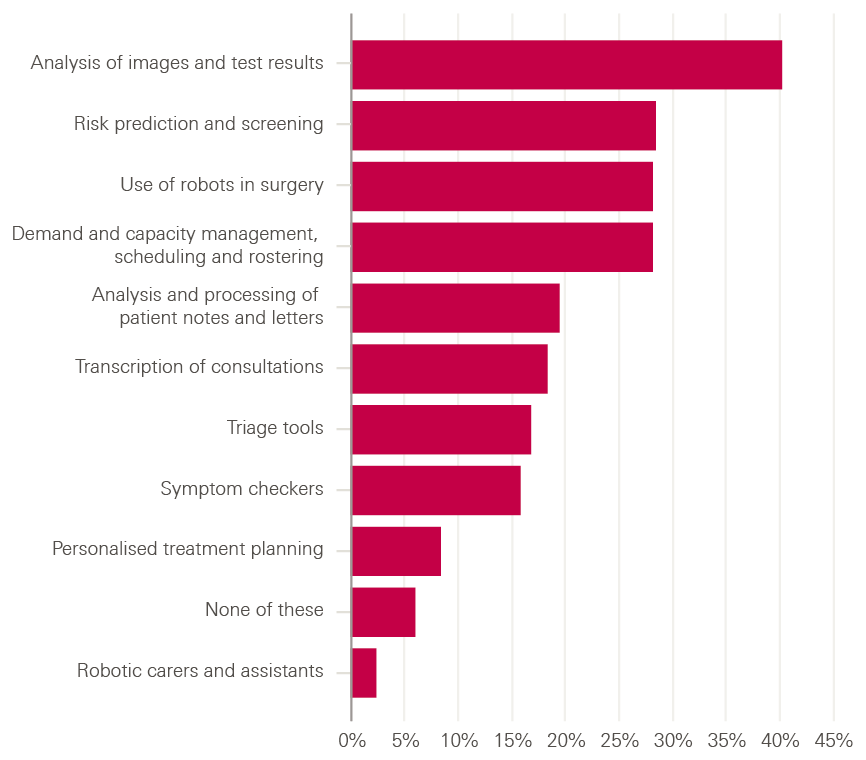

To further investigate attitudes to automation and AI in health care, we commissioned surveys of the UK public and NHS staff, conducted online by YouGov in October 2020, the results of which are described at various points throughout this report.

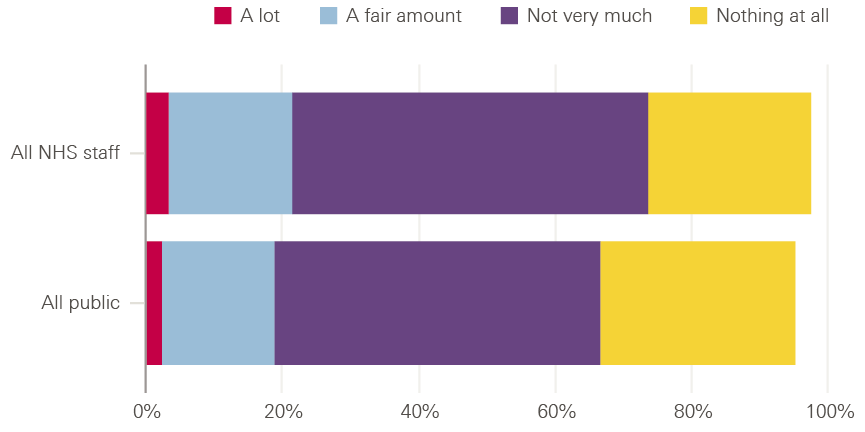

To start with, we asked people about their familiarity with the topic: specifically, how much they’d heard, seen or read about automation and AI in health care (respondents were provided with definitions and examples of these technologies). Some 29% of the public said they’d heard, seen or read ‘nothing at all’ about it. This was also true of 24% of the NHS staff surveyed – a striking reminder that, while there is real interest in this topic in many policy, academic and clinical communities, it remains far removed from the working lives of many NHS staff. While majorities of both the public and NHS staff surveyed had encountered something on this issue before, only 2% of the public and 3% of NHS staff surveyed said they’d heard, seen or read ‘a lot’, with 17% of the public and 18% of NHS staff saying ‘a fair amount’ and 48% of the public and 52% of NHS staff saying ‘not very much’. So there is clearly work to be done to engage with patients, staff and society as a whole to inform decisions about the future use of automation and AI in health care.

Figure 2: Public and NHS staff familiarity with automation and AI

In general, how much, if anything, have you heard, seen or read about automation and AI in health care (eg in the news, on social media, or from family, friends, colleagues, etc.)?

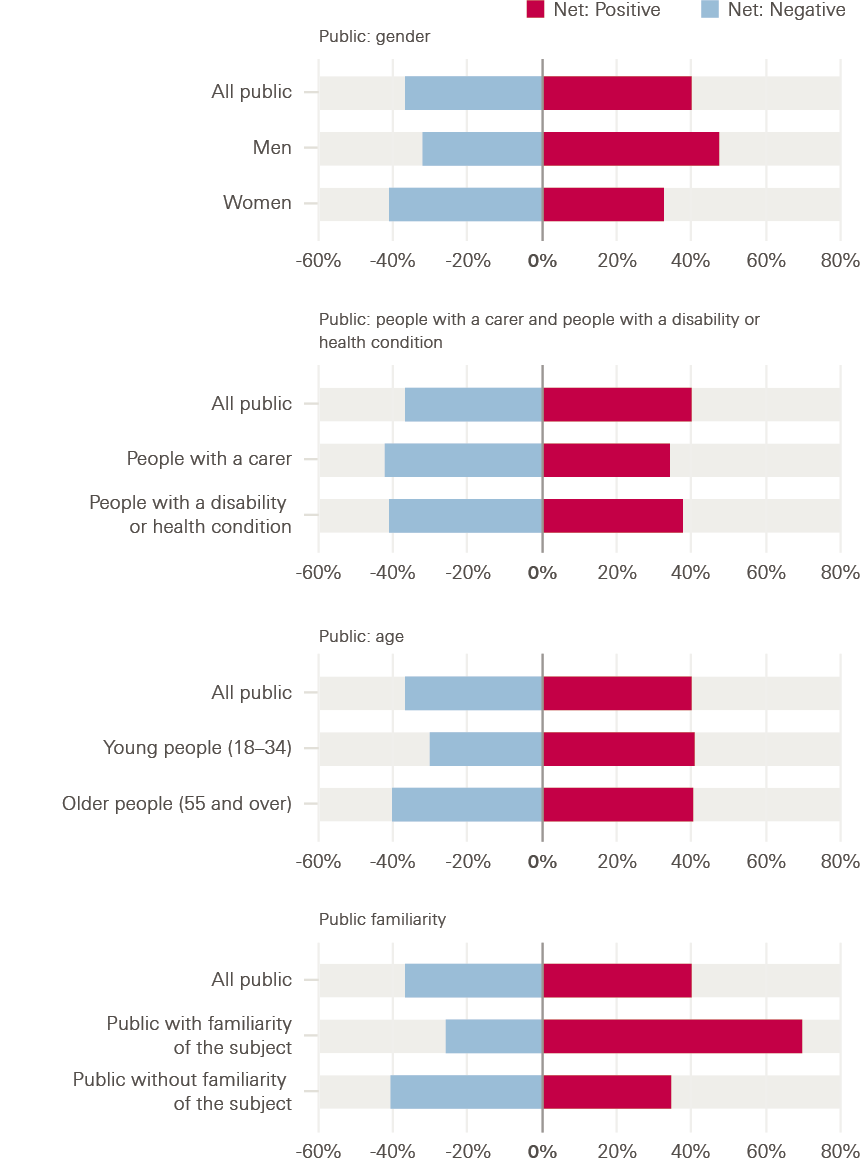

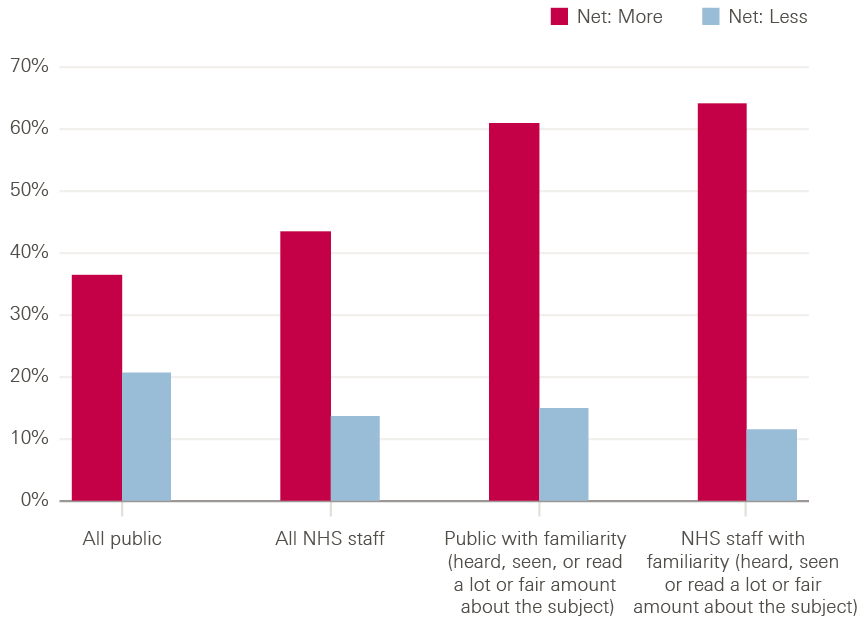

Our surveys also asked how positive or negative people felt about the use of automation and AI in health care – as a crude ‘temperature test’. In both the public and NHS staff surveys, more felt positive than negative, but opinion was closely balanced, with the public feeling more positive than negative by 40% to 37% and with NHS staff surveyed feeling more positive than negative by 40% to 36%.

There were some interesting differences underneath these headline figures. In the public survey, some groups were less positive about automation and AI in health care than others, including women, people with a health condition or disability and people with a carer. While men felt more positive than negative about the use of automation and AI by 48% to 33%, women felt more negative than positive by 41% to 33%. Similarly, people with a carer felt more negative than positive by 42% to 34%, as did those with a health condition or disability by 41% to 38%. Age is also sometimes highlighted as a factor affecting attitudes to technology, and there were some modest age differences within our results, with younger people (aged 18–34) feeling more positive than negative by 41% to 31%, while for older people (aged 55 or older) this margin was just 1 percentage point: 41% to 40%. More research is needed to understand why these differences exist, but they underline the importance of engaging with patients and the public in the development and deployment of automation and AI to co-design solutions, in order to help make sure these technologies work for everyone and that different preferences are taken into account.

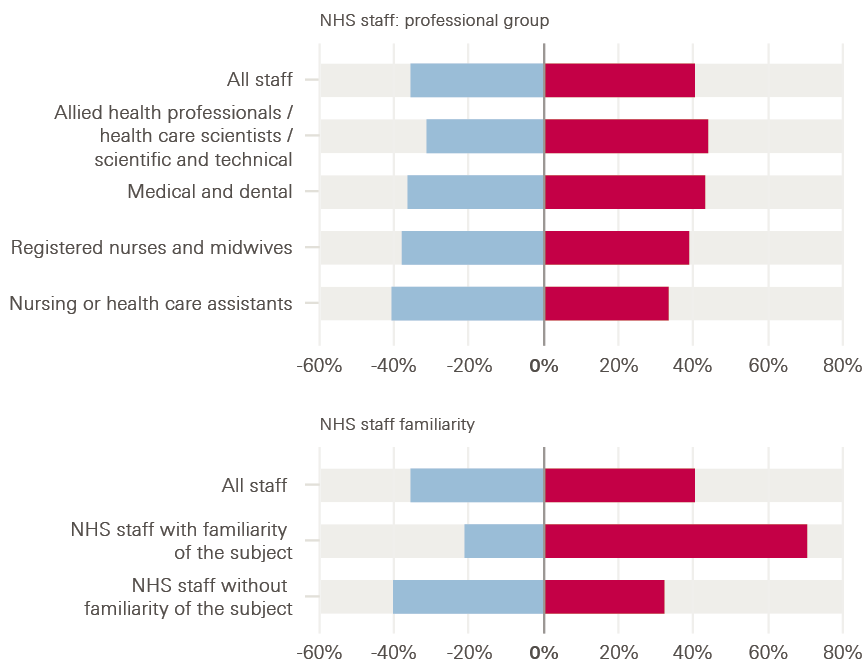

Among the NHS staff surveyed, there were some differences by professional group – perhaps reflecting the different perspectives that different staff groups will have on what these technologies might mean for health care. For example, medical and dental staff surveyed felt more positive than negative about the use of automation and AI in health care by 43% to 36%, and nurses and midwives by 39% to 38%, but health care assistants felt more negative than positive, by 41% to 33%.

However, these differences were dwarfed by the impact of familiarity with the topic. Among the public, those who said they had heard, seen or read ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ about automation and AI in health care felt much more positive than negative about the use of these technologies, by 70% to 26%, while those who answered ‘not very much’ or ‘nothing at all’ felt more negative than positive, by 41% to 35%. A similar pattern was evident in the NHS staff survey: those who said they had heard, seen or read ‘a lot’ or ‘a fair amount’ felt much more positive than negative about the use of automation and AI in health care, by 71% to 21%, while those who answered ‘not very much’ or ‘nothing at all’ felt more negative than positive, by 40% to 32%. This suggests that helping to familiarise people with this topic could play an important role in shaping attitudes to this agenda in future.

Figure 3: Public and NHS staff attitudes to the use of automation and AI in health care

Overall, how positive or negative do you feel about the use of automation and AI in health care?

Having explored the current context for automation and AI, in the next chapter we look at some of the opportunities to apply these technologies in health care.

* One fact that is often cited is the ongoing growth of the health care workforce. See for example The health care workforce in England: Make or break? The Health Foundation, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust; 2018.

† Some are concerned by the use of robotic surgery for common surgical procedures with limited evidence and unclear clinical benefit. A recent UK study found no evidence of a difference in 90-day postoperative hospital days between robotic and laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Sheetz and colleagues argue that the use of robotic surgery has outpaced the generation of evidence to demonstrate its effectiveness. See Olavarria O, Bernardi K, Shah S, Wilson T, Wei S, Pedroza C, Avritscher E, Loor M, Ko T, Kao L, Liang M. Robotic versus laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: multi-center, blinded randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2020; 370; Sheetz K, Claflin J, Dimick J. Trends in the Adoption of Robotic Surgery for Common Surgical Procedures. JAMA Network Open. 2020; 3(1): e1918911.

‡ Respondents were asked for their views on a range of hypothetical scenarios.

§ A total of 45% felt that AI should be used for helping to diagnose diseases, as opposed to 34% who did not. On the other hand, 63% felt that AI should not be used for taking on tasks usually performed by doctors or nurses, compared with only 17% who felt it should be.

¶ Survey of 69 trainees and resident diagnostic radiologists at a single radiology residency training programme.

** Most GPs believed it unlikely that technology will ever be able to fully replace physicians for diagnosing patients (68%), referring patients to other specialists (61%), formulating personalised treatment plans (61%) and delivering empathic care (94%). On the other hand, 80% believed it likely that future technology will be able to fully replace humans in undertaking documentation.

†† The other three are enhanced diagnostic decision making; delivery of remote care and self-management tools; and seamless sharing of patient information between care providers.

‡‡ UK public survey fieldwork done online by YouGov, 26–28 October 2020; total sample size 4,326 adults (85% from England, 8% Scotland, 5% Wales and 3% Northern Ireland); figures have been weighted and are representative of all UK adults (aged 18+). NHS staff survey fieldwork done online by YouGov 23 October–1 November 2020; total sample size 1,413 adults (80% from England, 13% Scotland, 6% Wales and 1% Northern Ireland); sample comprised the main occupational groups within the NHS’s clinical workforce (allied health professionals; medical and dental; ambulance; public health; nurses and midwives; nursing or health care assistants).

§§ Specifically, respondents were given the following information: ‘Automation is when computers and robots are used to do tasks that humans have traditionally done. In health care, examples of automation include using a machine to monitor a patient’s heart rate or using a robot to dispense medicines in a pharmacy. Artificial intelligence (AI) is when computers are able to copy aspects of human intelligence like learning and problem solving. In health care, examples of AI include using computers to predict which patients are more at risk of falling ill, or to analyse X-ray images in order to spot illness or injury.’

2. The potential for automation and AI in health care

2-1 Types of task amenable to automation

There are different ways of analysing and understanding tasks when considering what kinds of work can be automated and what cannot.

One influential approach, by economist David Autor, focuses on the broad nature of tasks and views the degree of routine involved in a task as a key determinant of automatability. Autor categorised tasks based on two properties: routine versus non-routine, and manual versus cognitive. Routine manual tasks require what Autor calls a ‘methodical repetition of an unwavering procedure’, such as picking and sorting items and repetitive assembly – the kind of repetition that could be explicitly programmed and performed by machines. Non-routine manual tasks, on the other hand, such as caretaker work and truck driving, are considered to have more limited scope for automation in Autor’s model. Routine cognitive tasks include record keeping and repetitive customer services like bank clerk work, and these are thought to offer substantial room for automation. Finally, non-routine cognitive tasks, which include medical diagnosis, legal writing and sales, are not seen to be candidates for automation and are viewed as more likely to remain (at least partially) in the domain of human performance.

Autor’s analysis has shone a light on labour market trends such as the ‘disappearing middle’, whereby – contrary to earlier predictions – many manual, non-routine jobs have remained resistant to automation, while other ‘white collar’ jobs, such as clerical work, have been automated. In these cases, it has been routine work that has been susceptible to automation, whether manual or cognitive, while non-routine work has proved harder to automate.

Autor’s analysis has been influential over many years, though technological advancements have led to certain non-routine tasks becoming easier to automate – truck driving, for example. Due to these advancements, some argue that automation can be extended to any non-routine task that is not subject to any ‘engineering bottlenecks’, which we discuss in more detail in Chapter 3.

This way of looking at tasks suggests that automation will tend to have most impact when applied to tasks that are frequent or time consuming, important and repetitive (though there can sometimes be benefits to applying automation to infrequent tasks too – for example, when a drug is rarely prescribed – as it is often these types of task where mistakes are most likely to occur). Such repetitive, rule-based tasks frequently lend themselves to a form of automation known as robotic process automation (RPA), which uses software to enable transaction processing, data manipulation and communication across multiple IT systems. RPA has successfully been deployed in many sectors to process invoices, claims and payments, monitor error messages and respond to routine requests from customers and suppliers.3 While RPA is not widespread in health care, a number of NHS trusts have successfully used it to manage scheduling and other processes, and NHSX is exploring how RPA can be scaled in the NHS through its Digital Productivity Programme.

A second approach to considering which kinds of task are amenable to automation is to analyse the skills and knowledge they require. The Oxford study used the O*NET database’s ‘occupation features’ to analyse how predictions of a task’s automatability related to the different skills and knowledge required. O*NET is a database of hundreds of standardised descriptors of almost 1,000 occupations in the US economy, which includes information on the skills, knowledge, work activities and interests associated with these occupations. The researchers looked at which features were clearly predictive of automatability and also at where an increase in the presence of a particular feature led to an increase in predicted automatability.

Table 1 presents the five largest (positive) percentage differences in O*NET occupational features for tasks that were rated automatable, not automatable and partly automatable, when compared to the entire dataset of health care tasks. Health care tasks predicted as ‘not-automatable’ require 26.0% higher personnel and human resources knowledge, 17.0% higher education and training knowledge and 18.7% higher management and financial resources skills. By contrast, ‘automatable’ tasks require 24.4% higher clerical skills.

Table 2 presents the occupational features with the largest positive influence on predicted task automatability, given an increase of the particular feature. Telecommunications and clerical knowledge have the largest gradient, meaning that if a task requires more of this, then its automatability score will increase to a greater extent than increasing other features.,

So these analyses suggest there might be a range of tasks in health care, especially clerical tasks, that could be promising candidates for automation.

Table 1: Largest feature differences relative to dataset by automatable category

|

Automatable category |

O*NET feature |

Feature difference |

|

Not automatable |

Installation (skill) |

+62.6% |

|

|

Building and Construction (knowledge) |

+27.2% |

|

|

Personnel and Human Resources (knowledge) |

+26.0% |

|

|

Management and Financial Resources (skill) |

+18.7% |

|

|

Education and Training (knowledge) |

+17.0% |

|

Automatable |

Clerical (knowledge) |

+24.4% |

|

|

Customer and Personal Service (knowledge) |

+13.2% |

|

|

Service Orientation (skill) |

+5.0% |

|

|

Economics and Accounting (knowledge) |

+4.7% |

|

|

Computers and Electronics (knowledge) |

+4.5% |

|

Partly automatable |

Medicine and Dentistry (knowledge) |

+30.8% |

|

|

Therapy and Counselling (knowledge) |

+22.0% |

|

|

Psychology (knowledge) |

+13.4% |

|

|

Clerical (knowledge) |

+13.2% |

|

|

Biology (knowledge) |

+12.1% |

Table 2: Ten largest O*NET occupational feature gradients

|

O*NET feature |

Feature gradient |

|

Telecommunications (knowledge) |

+0.167 |

|

Clerical (knowledge) |

+0.166 |

|

Wrist-finger Speed (ability) |

+0.153 |

|

Number Facility (ability) |

+0.118 |

|

Mathematics (skill) |

+0.093 |

|

Depth Perception (ability) |

+0.092 |

|

Building and Construction (knowledge) |

+0.09 |

|

Mathematical Reasoning (ability) |

+0.088 |

|

Economics and Accounting (knowledge) |

+0.085 |

|

Control Precision (ability) |

+0.082 |

Source: Willis M, et al.3

A third approach to thinking about the types of work that can be automated is to look at different task ‘functions’ and consider what level of automation might be appropriate in each case. To take one example, drawing on the different stages of human information processing, Parasuraman and colleagues describe four system functions that can potentially be automated: information acquisition, information analysis, decision and action selection, and action implementation. For each type of function there are different possible levels of automation. For example, with regard to decision making, a computer could suggest options to support human decision making, on the one hand, or it could actually make a decision and act autonomously, on the other; and there may be further levels in between, such as having a computer make the decision but still with the ability of a human operator to override it if necessary. Parasuraman and colleagues argue that a variety of factors will be relevant to determining the appropriate level of automation in different cases, especially the reliability of the automation technology, the potential impact on human performance in the resulting system and, crucially, the risks associated with decisions. So, for example, looking at air traffic control systems, they suggest that in the case of information acquisition and analysis, high levels of automation could be appropriate, while in the case of decision selection and implementation high levels of automation would only be appropriate for low-risk situations.

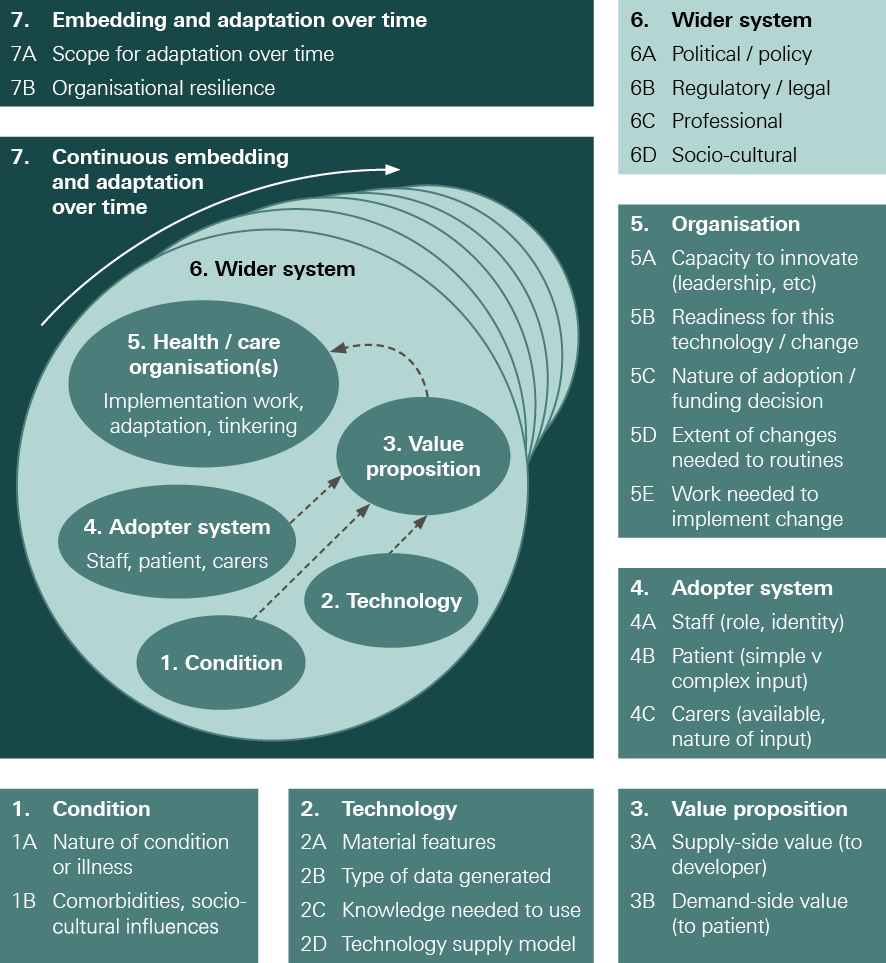

Work in health care is often complex and carries particular risks, with different kinds of tasks and work environments compared to other industries, and different legal, governance and institutional requirements. These factors might make it hard to translate some applications of automation from other industries to health care. This is explored in more detail in Chapter 3. First, we take a look at some specific areas where automation can be, and is being, applied in health care.

2-2 Application to administrative tasks in health care

Here we use the term ‘administrative’ loosely to mean tasks involved in the management or organisation of health care services, rather than in the direct delivery of them. Some administrative tasks may sit separately from clinical work, such as managing finances and payroll, while others may be embedded within it, such as processing prescriptions and managing hospital bed capacity.

Given that much administrative work involves routine information processing, the discussion above suggests that there may be significant opportunities for the automation of administrative tasks in health care. And with a high volume of administrative work in the NHS, it is easy to see why there is such appetite to take advantage of these opportunities, with the NHS Long Term Plan and NHSX both highlighting the potential of technology for reducing the burden of administrative work. Some administrative processes in health care are already being automated in particular settings, such as appointment booking and scanning letters in GP practices. However, advances in data availability, computational power and machine learning are creating possibilities for further automation.

The Oxford study estimated that around 44% of administrative tasks in general practice are ‘mostly’ or ‘completely’ automatable using current technology, based on its model derived from the opinions of automation experts (though, notably, the study also found that no single full-time role in general practice could be entirely automated). The research suggested that tasks such as managing finances and payroll, checking and sorting post, printing letters, texting patients, note-taking and letter scanning could all theoretically be automated. Given that such tasks require a considerable amount of time in any GP practice (including the time of GPs themselves), automating them could have a significant, positive impact in reducing the administrative burden and freeing up staff to focus on other work, particularly in light of current financial and workforce pressures.

Automation could make a particular difference with information-processing tasks that are time consuming and which have an important bearing on resources and patient care, such as in the management, scheduling and planning of clinical services. For example, in order to address high outpatient non-attendance rates, East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Foundation Trust has automated patient appointment reminders and cancellations using a simple text messaging process, reallocating free bookings when cancellations are made. The Trust claims that in 2018 this prevented 1,356 appointments being missed over a period of eight weeks, equivalent to a value of £216,960. Given the issue of non-attendance is common across health care services, this type of application could be useful in a range of other settings beyond secondary care, such as primary, community and mental health services.

Appointments and scheduling are also an area where AI and predictive analytics could add an extra dimension to automation. For example, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston is using the automated analysis of historical data to predict how much time a patient might need in the operating theatre and then using this to inform scheduling. AI can also help with the management of resources such as hospital beds. For example, funded by the Health Foundation, Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust has developed a model to predict rises in acute hospital bed occupancy (discussed in more detail in Chapter 3), which could be deployed to provide an early warning system that gives staff sufficient time to avert occupancy crises.

Advances in natural language processing (NLP), which can extract structured (machine analysable) data from unstructured narrative texts (such as clinical notes and letters), mean that automation technologies have increasing potential to support text-based administrative work, for example processing and producing letters – activities that require a significant amount of time across the NHS. In general practice, the Oxford study found that letter work – such as opening letters, triaging, scanning and redirecting them to relevant staff members, and responding to them in different ways – entails a large amount of work, which is typically undertaken by receptionists and secretaries, but also often by GPs. The study also found that a significant amount of time is spent trawling through letters to find small amounts of relevant information. Automation technologies using NLP could therefore be used to scan for relevant information and present it to health care professionals, prioritising information by context and urgency, as well as to produce letters automatically as patients have their examinations. In addition to helping make letter management in the NHS more efficient and less time consuming, such approaches could also open up opportunities for a wider range of communications options for patients, tailored to their needs and preferences, such as emails, texts, large print, braille, audio recordings and language translations. Another way NLP can be of particular value is in analysing and categorising patient feedback, which can then be used to target quality improvement work.

Box 5: Automated analysis of patient feedback

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (Innovating for Improvement, 2017–18)

Free-text patient experience feedback within the NHS Friends and Family Test (FFT) offers rich information for quality improvement. But many providers find it difficult to analyse and interpret because of the large volume of unstructured data and the challenge in linking the information to other quality indicators. Beyond missing out on opportunities to improve quality, asking for patient feedback without being able to analyse and act on it also raises ethical questions.

At Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHNT), the patient experience team received around 20,000 comments a month and were only able to analyse a small fraction of them. To address this issue, a multidisciplinary team from ICHNT and Imperial College London, supported by the Health Foundation, developed a tool which uses NLP to analyse free text comments in the FFT. The resulting analysis is then used to create easily digestible reports of patient experience at ward or service level, providing front-line staff with the information needed to devise effective quality improvement interventions.

Free-text FFT comments were collected in outpatient, inpatient, maternity and A&E services, with a view to improving care across these four areas. The team validated and then implemented the tool, which can analyse 6,000 comments in 15 minutes, compared with four days if the same analysis was undertaken by a member of staff. The time saved allows the patient experience team to spend more time supporting staff to act on patient feedback and improve services. For example, staff in the outpatient department were quickly able to identify improvements such as better informing patients of their position in the clinic queue and making water fountains available. Elsewhere, improvements were made to discharge processes through developing checklists.

While the project has enjoyed early success, to have greater impact and ensure sustainability for the long term the team are leading a drive to embed the tool into the workflows of all services in the Trust – helping to create a culture of ‘measurement for improvement’. This includes a strong focus on quality improvement methodologies, to ensure the patient feedback leads to positive change.

The team are also working with NHS England and NHS Improvement to spread the tool to other NHS trusts in England. A further Health Foundation grant is supporting the team to test and evaluate the wider application of this NLP platform across NHS trusts, in combination with quality improvement methodology.

‘For successful implementation, use and sustainability, you have to think beyond the shiny tool. It’s also about quality improvement, which takes thought, time and effort to embed.’

Erik Mayer, project lead

Given AI-driven advances in speech recognition, there is also significant potential for the automation of speech-related administrative tasks. For example, speech recognition could be used to streamline documentation tasks by using NLP to analyse patient–clinician conversations and create notes, turning a discussion into a text transcript, summarising and annotating it to provide clinically relevant information and categorising it to appropriate sections of the medical record. After the consultation, the clinician could review a summary for editing and saving (though see Chapter 3 on potential challenges with the automation of note-taking). An application such as this could also make connections with information already in the patient’s record, or with analysis of similar patients, to support clinical decision making. For example, Nuance Communications and Microsoft have developed a system that records each patient interaction and uses AI to convert it to text, which is then saved into the electronic health record.

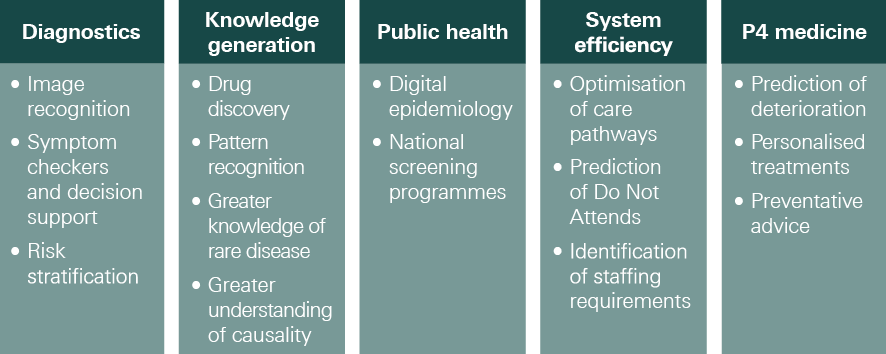

2-3 Application in clinical services

Beyond some of the established uses of automation in health care highlighted in Chapter 1, advances in computing, the codification of clinical knowledge and the availability of large datasets are creating scope for further automation of clinical tasks, or at least components of clinical tasks, especially those that relate to data analysis and decision selection. There is particular interest in the potential of data analytics and AI to support clinical decision making around diagnosis and treatment, where – as discussed above – the spectrum of automation could range from clinical decision support systems that assist human decision making all the way to scenarios in which decisions could be delegated to machines.

In many cases, these technologies are still in the early stages of development, testing and adoption, and the excitement about their potential currently outstrips the reality on the front line. Often, more real-world testing is required to investigate how technologies that have shown potential in the lab can be best deployed. For example, recent systematic reviews of studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy of AI-driven medical image analysis with that of health care professionals found that while many AI models demonstrated comparable accuracy, few studies were prospective or randomised trials in live clinical settings, nor did many present externally validated results. Nevertheless, there are a growing number of examples of automation and AI that have shown their potential, ranging along the whole patient pathway – from promotion and prevention, through diagnosis and treatment, all the way to rehabilitation and supporting people to live with long-term conditions. We highlight a few examples below.

Diagnosis: While AI has been applied to analyse a range of diagnostic data, some of the most impressive advances in recent years relate to diagnostic imaging. Machine learning potentially enables a high degree of accuracy in pattern recognition and the classification of images, with the ability to identify abnormalities, in some cases more acutely than the human eye. The application of machine learning in the analysis of medical scans and pathology slides therefore holds significant potential for supporting and improving the detection of diseases. Significant progress has been made in radiology, with AI being used in screening for conditions such as breast cancer. Studies show AI-powered screening systems can be a useful addition to the breast screening pathway; for example, one study by McKinney and colleagues showed that, while only tested using retrospective data, an AI system using deep learning improved specificity and sensitivity in predicting the development of malignancy when compared to a first clinical assessor and performed no worse in comparison to a second clinical assessor, including a reduction in the incidence of false positives and false negatives.

Risk assessment and prediction: AI can also assist clinical decisions by using data to assess risks and make predictions – for example, predicting if a patient’s condition is likely to deteriorate. For example, a project funded by the Health Foundation and led by King’s College London to improve outcomes in stroke care (described in more detail in Box 6) has developed a machine learning model that could be used to predict which patients are at highest risk of mortality after stroke. At a population level, AI could also be used for risk stratification and public health surveillance, such as for disease outbreak prediction and surveillance, something that could be particularly helpful in anticipating future waves of COVID-19 as well as the spread of other diseases.

Box 6: Machine learning analytics for quality improvement in stroke care

King’s College London (Insight, 2017–2021)

Variation in stroke outcomes is a complex phenomenon, meaning it can be difficult to predict the likelihood of disability after stroke. While there is an increasingly large and detailed amount of health data available, it can be challenging to translate this into knowledge that can be used to improve care quality.

This project, led by King’s College London, funded as part of the Health Foundation’s Insight programme, sought to address these challenges by using more sophisticated methods to analyse clinical audit data contained in the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP). The project developed machine learning algorithms to predict mortality after stroke, which were trained using SSNAP data from 488,497 patients. The performance of these machine learning methods was then compared to models using traditional statistical methods.

Compared to logistic regression, the machine learning model was slightly more accurate in predicting 30-day mortality after stroke. The largest accuracy gains were demonstrated when a wider range of potential variables were available to make predictions from, which underlines the importance of high-quality data if the benefits of using more advanced forms of predictive analytics such as machine learning are to be realised in health care.

More accurate predictions of outcomes after stroke could potentially be used to aid patient management, such as identifying early which patients might benefit from more intensive monitoring and management. They could also be used to analyse how services are performing, to support quality improvement and identify best practice where services are delivering better than expected care. The project team are also now looking at the potential of this technique to predict stroke-associated pneumonia.

‘Health services will need to invest resources in generating better quality data, otherwise the gains from using more advanced methods for predictive analytics will be limited.’

Triage: There is also increasing interest in the potential of AI to help clinicians make triage decisions and to help patients assess their own symptoms. Several AI triage tools are currently being tested, although these are currently intended to support clinicians in decision making, rather than to make triage decisions themselves. For example, a Health Foundation-funded project led by Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust is developing a system to assist the emergency department triage process by quickly identifying high-risk patients needing urgent care, described in more detail in Box 13 (page 46).

Patient-facing symptom checkers: A number of companies have also developed patient-facing symptom checkers that are currently available in the UK. These are ‘chatbots’ that use AI to compare data gathered from the patient with medical knowledge, with the aim of helping people get a better understanding of when to seek medical attention and connecting them to the appropriate service. For example, Your.MD and Babylon Health have both developed symptom checkers that ask users a series of questions to build a picture of their symptoms, before suggesting the most appropriate course of action, such as recommending a visit to the GP or hospital or providing reassurance that the person can take steps to recover at home. Babylon claims its chatbot has been trained to recognise the ‘vast majority of health care issues seen in primary care’, although as of May 2021 it also says it is not suitable for people with mental health concerns, skin problems, and pregnancy or post-natal concerns, among others, recommending an appointment with a doctor., University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust is now working with Babylon to use this technology to develop a pre-hospital triage app for people considering using A&E services, as part of a drive to reduce unnecessary A&E attendances.

Treatment decisions and planning: As well as diagnosis and triage, data tools and AI can also be used to support better treatment decisions and planning, by suggesting treatment options or creating prompts and reminders to optimise the delivery of treatment. AI can be coupled with a range of patient data, including genomics data, as well as research and best practice, to help tailor treatments to individual patients. Electronic prescribing systems, for example, can incorporate decision support tools to check dosages and potential interactions with other drugs or conditions, and suggest safer or better-value alternatives. Used in this way, decision support systems – while stopping well short of complete automation – can be a useful tool in promoting adherence to best practice and helping reduce errors and unwarranted variation. In the case of electronic prescribing systems, for example, studies suggest that when used effectively these systems can reduce medication errors and adverse drug events,, although there is more work required to ensure they are consistently safe and effective.,

Health promotion and self-management: Automation and AI are also increasingly supporting people to manage their own health. For example, a range of technologies, such as apps, wearables and medical devices, are enabling health monitoring and management in homes and residential care settings. One example is the latest generation of insulin pumps, which combine continuous glucose monitors with smart algorithms that automatically adjust dosage.

Quality improvement: These technologies can also play an important role in supporting quality improvement by helping to generate data and analysis about how services are performing and how they can be improved – critical components of a learning health system. The projects at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and King’s College London described above, which are using machine learning to analyse patient feedback and clinical audit data, demonstrate how AI can be used to help identify where improvements can be made.

In many of the areas highlighted above, robotics can be combined with AI to automate tasks that require movement as well as information processing. The example of surgery has already been highlighted. Another area where this has potential is medication dispensing and stock management in hospitals and community pharmacies; robotic dispensers can operate with greater speed and precision than humans, with a significantly lower risk of error., A further application of robotics in clinical settings is transportation. For example, Moxi is a robotic assistant with a mobile base, arm and gripper, reportedly being trialled in the US, designed to assist clinical staff by transporting supplies to patient rooms and delivering lab samples. Robotic technologies also present opportunities to provide therapy, whether in the home or in a variety of care settings. For example, Paro is a therapeutic AI robot, designed to look like a seal, to support people with dementia, which has shown signs of being able to reduce agitation and improve verbal and visual engagement among users.

While at present several of the technologies reviewed here currently require human supervision or input, and so are not examples of full automation, they could conceivably become more independent in future. Either way, used effectively, they have the potential to improve outcomes, experience and efficiency, as well as to help alleviate workforce pressures.

Box 7: NHSX

NHSX, a joint venture between NHS England and NHS Improvement and the Department of Health and Social Care, provides leadership for digital transformation in health and social care, focused on five missions:

- reducing the burden on clinicians and staff, so they can focus on patients

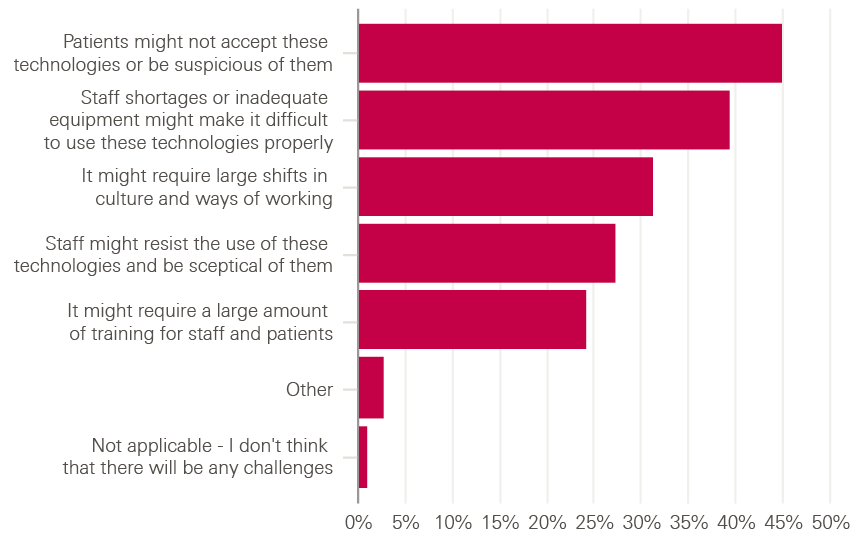

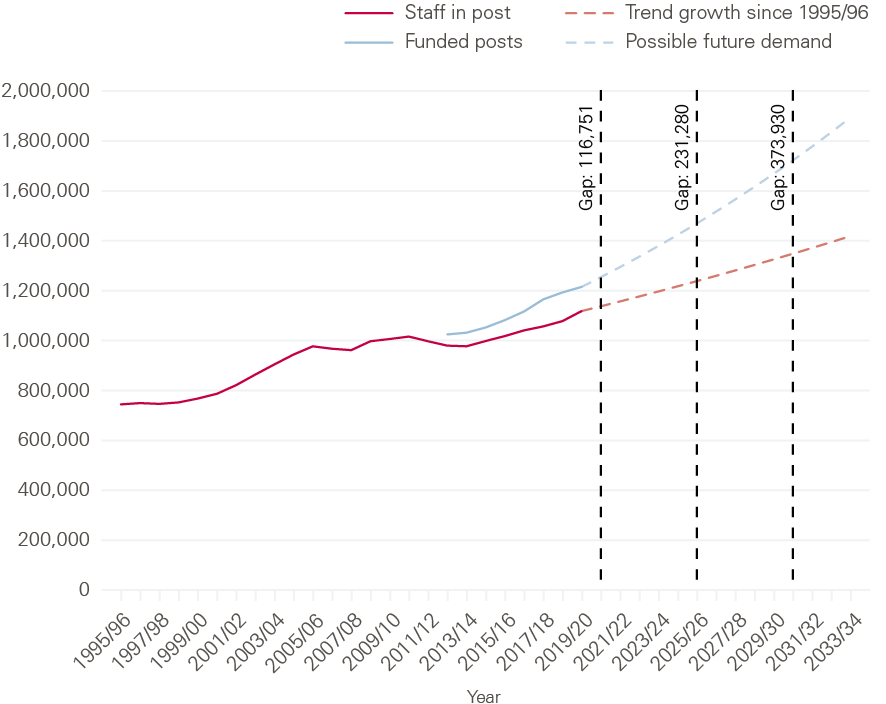

- giving people the tools to access information and services directly