Introduction

Why does quality improvement matter?

Every health care system is built on a complex network of care processes and pathways. The quality of the care delivered by the system depends to a large extent on how well this network functions, and how well the people who provide and manage care work together.

The overall aim is simple: to provide high-quality care to patients and improve the health of our population. Yet, as every patient and professional can testify, for every process or pathway that works well, there is another that causes delay, wasted effort, frustration or even harm.

Quality improvement is about giving the people closest to issues affecting care quality the time, permission, skills and resources they need to solve them. It involves a systematic and coordinated approach to solving a problem using specific methods and tools with the aim of bringing about a measurable improvement.

Done well, quality improvement can deliver sustained improvements not only in the quality, experience, productivity and outcomes of care, but also in the lives of the people working in health care. For example, it can be used to improve patient access to their GP, streamline the management of hospital outpatient clinics, reduce falls in care homes, or tackle variations between providers in the way processes and activities are delivered.

An understanding of quality improvement is therefore important for anyone who delivers or manages care, as well as for people using care services and wondering how they could be improved. Through quality improvement there is the potential to create a health care service capable of ensuring ‘no needless deaths; no needless pain or suffering; no helplessness in those served or serving; no unwanted waiting; no waste; and no one left out’.

What is this guide about?

This guide offers an explanation of some popular quality improvement approaches and methods currently used in health care and their underlying principles. It also describes the factors that can help to make sure these approaches and methods improve quality of care processes, pathways and services.

There are other methods and interventions that can improve quality of care, such as education, regulation, incentives and legal action, but these are outside the scope of this guide.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is written for a general audience and will be most useful to those new to the field of quality improvement, or those wanting to be reminded of the key points. It is aimed primarily at people either working in or receiving health care, but is also relevant to social care and other public and third sector services, such as housing and education.

What is quality and how can it be improved?

What is quality?

Within health care, there is no universally accepted definition of ‘quality’. However, the majority of health care systems around the world have made a commitment to the people using and funding their services to monitor and continuously improve the quality of care they provide.

In England, the NHS is ‘organising itself around a single definition of quality’: care that is effective, safe and provides as positive an experience as possible by being caring, responsive and personalised. This definition also states that care should also be well-led, sustainable and equitable, achieved through providers and commissioners working together and in partnership with, and for, local people and communities (see Box 1).

Box 1: The dimensions of quality

People working in systems deliver care that is:

Safe Avoiding harm to people from care that is intended to help them.

Effective Providing services that are informed by consistent and up-to-date high-quality training, guidelines and evidence.

Caring Delivering care with compassion, dignity and mutual respect.

Responsive and personalised Ensuring services are shaped by what matters to people, and empowering people to make informed decisions and design their own care.

Health care organisations and systems are:

Well-led Driven by collective and compassionate leadership, underpinned by a shared vision, values and learning, a just and inclusive culture and proportionate governance.

Sustainably-resourced Focused on delivering optimum outcomes within available finances, and reducing the negative impact on public health and the environment.

Equitable Committed to understanding and reducing variation and inequalities and ensuring that everybody has access to high-quality care and outcomes.

It is important that health care organisations consider all these dimensions when setting their priorities for improvement. Often the dimensions are complementary and work together. However, there can sometimes be tensions between them that will need to be balanced. It is therefore necessary to consider all stakeholders’ views and to work together to identify improvement priorities for an organisation or local health care system.

How can we improve quality?

A long-term, integrated whole-system approach is needed to ensure sustained improvements in health care quality. Several factors (also discussed in Sections 3 and 5) are required to drive and embed improvements in a health care organisation or system.,,,,,

Leadership and governance

- Establishing effective leadership for improvement.

- Creating governance arrangements and processes to identify quality issues that require investigation and improvement.

- Adopting a consistent, aligned and systematic approach to improving quality.

- Developing systems to identify and implement new evidence-based interventions, innovations and technologies, with the ability to adapt these to local context.

Improvement culture, behaviours and skills

- Building improvement skills and knowledge at every level, from the top tiers of organisations, such as the boards of acute trusts or primary care networks, through to front-line staff.

- Recognising the importance of creating a workplace culture that is conducive to improvement.

- Giving everyone a voice and bringing staff, patients and service users together to improve and redesign the way that care is provided.

- Flattening hierarchies and ensuring that all staff have the time, space, permission, encouragement and skills to collaborate on planning and delivering improvement.

External environment

- Policy and regulatory bodies supporting efforts to develop whole-system approaches to improvement.

- Government ensuring that health and care services are appropriately resourced to deliver an agreed standard of quality.

What does quality improvement involve?

Quality improvement draws on a wide variety of approaches and methods, although many share underlying principles, including:

- identifying the quality issue

- understanding the problem from a range of perspectives, with a particular emphasis on using and interpreting data

- developing a theory of change

- identifying and testing potential solutions; using data to measure the impact of each test and gradually refining the solution to the problem

- implementing the solution and ensuring that the intervention is sustained as part of standard practice.

The successful implementation of the intervention will depend on the context of the system or the organisation making the change and requires careful consideration. It is important to create the right conditions for improvement and these include the backing of senior leaders, supportive and engaged colleagues and patients, and access to appropriate resources and skills.

Underlying principles

When participating in an improvement intervention for the first time, it is not necessary to be an expert in quality improvement approaches and methods. However, before starting it is important to understand the core underlying principles that are common to most approaches and methods currently being used in health care.

Understanding the problem

Before thinking about how to tackle an improvement problem, it is important to understand how and why the problem has arisen. Taking the time to do so, preferably by using a variety of data and in collaboration with a range of staff and patients, will help to avoid the risk of tackling the symptoms of the problem instead of its root cause.

One tool that can be used to identify the causes of the problem is a ‘cause and effect’ or ‘fishbone’ diagram, which is designed to enable teams to identify all potential causes, not just those that are most obvious. After identifying the most likely causes, teams can use a range of tools to investigate them further, such as patient interviews, surveys and process mapping.

Process mapping is a tool used to chart each step of a process. It is used to map the pathway or journey through part, or all, of a patient’s health care journey and its supporting processes. Process mapping is especially useful as a tool to engage staff in understanding how the different steps fit together, which steps add value to the process, and where there may be waste or delays. Mapping patient journeys involving multiple providers is also important to identify any quality problems that occur at the interfaces between teams and organisations.

Designing improvement

It is important to allow enough time to design an improvement intervention and plan its delivery. Developing a specific aim and clear, measurable targets is essential. Another key step is to align the aim of the intervention with wider service, organisational or system goals. This can help to attract support and resources from leaders and managers for a smooth implementation.

It is also important to consider any challenges that will need to be addressed for the intervention to achieve its aims. A driver diagram is a useful way of capturing these key issues and identifying the activities required to tackle them. A logic model, which sets out a theory of change about how an intervention is supposed to work, is another helpful tool.

When identifying an intervention, it is useful to look at how other teams have addressed similar improvement challenges. As well as providing insights about what has and has not worked in other contexts, it can help to avoid the risk of ‘reinventing the wheel’ by repeating work that has already been carried out elsewhere.

Data and measurement for improvement

Measurement and gathering data are vital elements of any attempt to improve performance or quality and are needed to assess the impact against set objectives. When trying to assess the impact of a change to a complex system, a combination of measures is often used, such as process and outcomes measures. Measuring for improvement aims to identify the changes that occur while the intervention is being tested so that the intervention can be refined over time in response to these data.

To measure change it is important to capture a baseline and then carry out measurement at regular intervals to gauge whether the impact of the intervention represents an improvement or deterioration compared to the expected level of performance variation.

It is also important to measure ‘what would have been’ without the intervention, bearing in mind any potential external causes of change seen in measurement. This can be done using statistical process control (SPC), a method that examines the difference between natural variation (common cause variation) and variation that can be controlled (special cause variation). SPC uses control charts that display boundaries (control limits) for acceptable variation in a process.

Improving reliability

A key focus of quality improvement is to improve the reliability of the system and clinical processes. Ensuring reliability mitigates against waste and defects in the system and reduces error and harm. Analysis of high reliability organisations, many of which can be found in industries that have developed and sustained high levels of safety, such as commercial aviation and nuclear power industries, has identified a number of common attributes and behaviours. These include a culture of ‘collective mindfulness’ in which staff routinely look for and report minor safety problems and share a willingness to invest time and resources in identifying and learning from errors.

In health care, systematic quality improvement approaches such as Lean (see Section 4) have been used to:

- redesign system and clinical pathways

- create more standardised working procedures

- develop error-free processes that deliver high quality, consistent care and use resources efficiently.

Other health care organisations have taken a proactive approach to safety by developing the capacity to detect and assess system-level weaknesses (hazards and their associated risks) and introducing interventions to address them (risk controls).

Demand, capacity and flow

Some backlogs and delays in health care services are attributable to resource shortages or increases in demand. A case in point is the backlog of appointments and procedures created by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, not all delays are the result of capacity problems. It may be that the capacity is in the wrong place or is provided at the wrong time. To understand whether there is a capacity shortfall in a service, it is necessary to measure the demand (the number of patients requiring access to the service) and the flow (how and when a need for a service is met).

For a process improvement to be made, there needs to be a detailed understanding of the variation and relationship between demand, capacity and flow. For example, demand is often relatively stable and flow can be predicted in terms of peaks and troughs. In this case, it may be the variation in the capacity available that causes the problem (for example, how work plans are scheduled, staff sickness, and planned or unplanned leave).

The relational aspects of improvement

When planning, designing and testing an improvement intervention it is important to focus not just on the technical aspects of improvement, such as how to apply quality improvement methods and tools and to measure change, but also on the relational aspects of improvement. The way in which the team of people leading the intervention work together and how they communicate with others whose support they need, is likely to have a profound influence on the success of the intervention. These relational issues are discussed in the remaining part of this section.

Involving and engaging staff

Evidence about successful quality improvement indicates that the method or approach used is not the sole predictor of success, but rather it is the way in which the change is introduced. Factors that contribute to this include leadership, effective communication, staff engagement and patient participation, as well as training and education.

Engaging the people closest to the issue being addressed is especially important, but it can be challenging. For example, many clinicians will be keen to improve the quality of the service they offer and may already have done so through methods such as clinical audit, peer review and adoption of best practice. However, they may be unfamiliar with quality improvement approaches. For this reason, capability building and facilitated support are key elements of building clinical commitment to improvement. Other important aspects include:

- involving the clinical team early on when setting aspirations and goals

- ensuring senior clinical involvement and peer influence

- obtaining credible endorsement – for example, from the royal colleges

- involving clinical networks across organisational boundaries

- providing evidence that the change has been successful elsewhere

- embedding an understanding of quality improvement into training and education of health care professionals.

Clinicians are more likely to engage with the process if the motivation and reasons focus on improving the quality of patient care rather than on cost-cutting measures.

Nonetheless, it is important to ensure that all relevant staff are engaged, not just clinicians. Managers, for example, can help to ensure that improvement is embedded into standard practice and non-clinical staff, who are often the first point of contact for patients, play a key role in improving care. Breaking down traditional hierarchies for this multidisciplinary approach is essential to ensure that all perspectives and ideas are considered.

Co-producing improvement

At its best, quality improvement in health care is built on an equal partnership between staff, patients, carers and the wider public. These partnerships are part of a desire to move away from a staff-driven approach to improving care, in which patients are sometimes invited to participate, to a model where staff and patients make decisions that relate directly to the patient’s care together.

Underpinning these partnerships is a shared purpose, which is informed by discussions on what matters most to patients and where they think improvement efforts should be focused. Trust, openness and an ability to listen respectfully are key to the success of these discussions. A willingness to confront any power imbalances among participants, making it difficult for some participants to contribute equally, is also important.

Creating such an environment is not always straightforward: patients may need support and training to make the transition to being ‘makers and shapers’ of services, while professionals may need guidance on addressing certain issues, such as unconscious bias.

It is important that organisations invest resources into patient and public involvement in improvement and build up the necessary skills and knowledge to maximise the time, expertise and commitment of patients, carers and the wider public.

Building effective teams

How improvement team members relate to each other and work together has a critical bearing on the success of the intervention. Treating each other with respect and courtesy, listening carefully to the views of others and valuing their ideas, regardless of their hierarchical position, are all behaviours that can help the team to work together more effectively.

Equally important are a willingness to learn together and a sense of humility, founded on an awareness that no single person has the skills and experience to solve a problem on their own. Any team disagreements should be resolved through open discussion, rather than by personal or positional power.

Other vital attributes are the ability to ask questions clearly and frequently, and to share knowledge and thoughts in a focused and timely fashion. These ‘teaming’ skills help team participants to interact effectively and efficiently.

Collaboration

Collaboration is an essential component of effective learning and improvement. Working collaboratively and outside of traditional organisational boundaries often provides the basis for understanding and addressing improvement challenges. Networks and partnerships such as clinical audit networks, academic health science networks, primary care networks, the Q community (see Section 6) or other similar groups enable the sharing of experiences, knowledge and expertise within local health systems.

Collaboration also provides opportunities for scaling up of techniques, learning and discussion and can drive continued developments in quality improvement. Health care quality improvement strategies developed through collaborative networks can be shared and adopted at regional or national levels and therefore have a wider uptake than those developed locally. This raises the standard of quality and consistency of care across a broader landscape.

Approaches and methods

Many of today’s quality improvement approaches and methods were originally developed in industry and have been adapted for use in other sectors, such as health care. These industrial approaches have been used extensively within health care for the past 30 years to improve specific care processes and pathways, but their use has only been embedded throughout a few large health care provider organisations (see Section 5). Perhaps because of this, the evidence base for their effectiveness is relatively limited, although it is expanding with the increasing levels of research into the implementation and impact of quality improvement interventions.

The roots of many quality improvement approaches and methods can be traced back to the thinking about production quality control that emerged in the early 1920s. During the 1940s and 1950s, quality improvement techniques were further developed in Japan, pioneered there by the American experts W Edwards Deming, Joseph Juran and the Japanese expert Kaoru Ishikawa. More recently, Don Berwick has become known for his work in the US, leading the pioneering work of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (see Section 6). Several quality improvement approaches and methods draw from the work of these pioneers.

This section describes some of the most popular quality improvement approaches and methods. The evidence has not yet evolved to the point where one approach can be recommended above another. The choice of approach or method is likely to depend to some extent on the nature of the problem being addressed and its context. Whatever approach or method is used, discipline is important, particularly in terms of fidelity to the underlying principles described in Section 3.,

Model for improvement

This is an approach to continuous improvement where changes are tested in small cycles that involve planning, doing, studying, acting (PDSA), before returning to planning, and so on., These cycles are linked with three key questions.

- ‘What are we trying to accomplish?’

- ‘How will we know that a change is an improvement?’

- ‘What changes can we make that will result in improvement?’

Each cycle starts with hunches, theories and ideas and helps them evolve into knowledge that can inform action and, ultimately, produce positive outcomes. To measure the impact of each change, tools such as control charts are used (see Section 3).

Lean

This approach has its origins in Japan’s car industry. It is a quality management philosophy based on two core values – to make customer value flow and respect for people. In health care, Lean emphasises the patient’s central position to all activities and aims to eliminate or reduce activities that do not add value to the patient. This is achieved by applying Lean’s operational principles, which involve five steps for continuous improvement.

- Defining what is value-adding to patients.

- Mapping value streams (pathways that deliver care).

- Making value streams flow by removing waste, delay and duplication from them.

- Allowing patients to ‘pull’ value, such as resources and staff, towards them, so that their care meets their needs.

- Pursuing perfection as an ongoing goal.

Clinical microsystems

These are small groups of people who work together regularly to provide care to a specific group of patients.,, This approach is based on the principle that the quality, safety and person-centredness of an entire health care system is largely determined by what happens in its constituent microsystems.

A systematic approach has been developed to improve microsystems focused on the 5Ps: patients, people, patterns, processes and purpose. Assessing the 5Ps helps to identify opportunities for improvement, which are then addressed using the model for improvement approach.

Experience-based co-design

This is an approach that was designed in the UK – for and with the NHS. It aims to improve patients’ experience of services, through patients and staff working in partnership to design services or pathways., Data are gathered through in-depth interviews, observations and group discussions and analysed to identify ‘touch points’ – aspects of the service that are emotionally significant. Staff are shown an edited film of patients’ views about their experiences, before staff and patients come together in small groups to develop service improvements.

Key questions for planning and delivering quality improvement

Q. What are the challenges to delivering quality improvement?

A. In a review of 14 quality improvement programme evaluations funded by the Health Foundation, 10 key challenges were consistently identified from the programmes. These were:

- convincing peers that there is a problem

- convincing peers that the solution chosen is the right one

- getting data collection and monitoring systems right

- excess ambitions and ‘projectness’ – treating the intervention as a discrete, time-limited project, rather than as something that will be sustained as part of standard practice

- the organisational context, culture and capacities

- tribalism and lack of staff engagement

- leadership

- balancing carrots and sticks – harnessing commitment through incentives and potential sanctions

- securing sustainability

- considering the side effects of change.

However, the review also showed that if you take the time to get an intervention’s theory of change, measurement and stakeholder engagement right, this will deliver the enthusiasm, momentum and results that characterise improvement at its best.

Q. Can quality improvement have unintended consequences?

A. Quality improvement does not always work and can have the unintended consequence of diverting resource and attention without producing benefit. Sometimes, change in one area can cause a negative effect in another, for example, improved early discharge might lead to increased readmission. In other instances, the overall impact of a quality improvement effort may be negative. Leaders need to anticipate and monitor for these potential unintended consequences using a set of balancing measures and may need to make decisions about scheduling or sequencing of initiatives.

The scale of a quality improvement intervention, and the extent to which it is coordinated with other improvement efforts, also matters. An isolated small-scale intervention to solve a problem in a specific team or service may end up duplicating work carried out elsewhere or, by adopting a solution that varies from standard practice, it could create a potential safety risk.

Quality improvement is likely to be more effective if it is undertaken as a health care organisation or system-wide effort. Improvements to care processes and pathways need to be considered holistically, rather than as disconnected interventions, and then approached as a long-term, sustained change effort. An integrated, system-level approach also allows a broad range of skills and expertise to be deployed to solve improvement challenges.

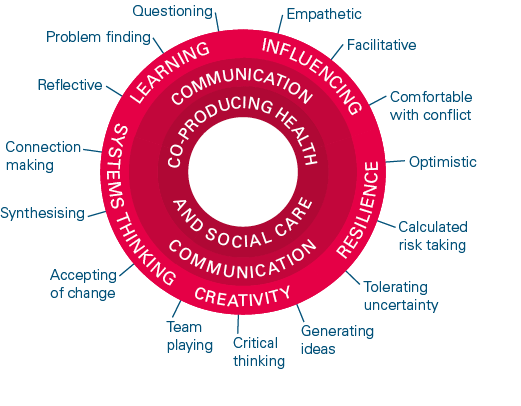

Q. What skills do improvers need?

A. Quality improvement requires both technical and relational skills., As well as understanding how to plan, implement, measure and refine improvement interventions using recognised methods, such as PDSA cycles, improvers need to be able, among other things, to describe their intervention effectively and convince others to work with them. Negotiation skills, the ability to read people and situations effectively and work well in a team are vital to getting an intervention up and running.

Practical skills, such as the capacity to manage time effectively, identify the right priorities, and keep a project delivery plan on schedule, are also essential. Equally important are learning skills, particularly the ability to reflect, both individually and as a group, on the lessons learned from each step of an intervention – and to use these learnings to refine the improvement approach. Successful improvers have often developed certain ‘improvement habits’, which help them to get their ideas off the ground and ensure that their intervention is sustained. These habits are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The habits of improvers

Source: The habits of an improver: Thinking about learning for improvement in health care. The Health Foundation; 2015.

Q. What role do senior leaders play in quality improvement?

A. Support from senior organisational or system leaders is often vital to the success of an improvement intervention. As well as ensuring that improvement teams have the resources they need to plan and deliver their intervention, senior leaders in large provider organisations, such as NHS trusts, can help to unblock barriers and give teams the time and space to test and refine their intervention.

Senior leaders, particularly board members, also have a critical role to play in creating a positive organisational culture, which has consistently been associated with improved quality outcomes., They can do this by placing improvement at the centre of their organisational strategy and fostering a learning culture in which front-line teams feel psychologically safe to question existing practice, report errors and try new methods.

Q. Can quality improvement approaches be applied across whole organisations?

A. There are many examples of the successful use of quality improvement methods to improve processes and outcomes in individual teams, services and care pathways in primary, secondary, community and social care settings. However, it is rarer to see these methods implemented in a coordinated and systematic way across large provider organisations or whole health systems.

A study of 1,200 US hospitals found that although 69% had adopted a quality improvement approach such as Lean, only 12% had reached a ‘mature, hospital-wide stage of implementation’. This is due, in part, to the fact that it takes a great deal of time, resources and planning to implement an organisation-wide approach to improvement. However, many health care providers from around the world that have adopted an organisation-wide approach believe that the investment required has been justified by the long-term performance benefits it has delivered. In England, for example, many of the NHS trusts rated as outstanding by the Care Quality Commission have an established organisation-wide improvement approach in place.

Health Foundation analysis has found that effective organisation-wide approaches to improvement consist of four key elements.

- Leadership and governance. Visible and focused leadership, for example, in an NHS trust, at board level, accompanied by effective governance and management processes that ensure all improvement activities are aligned with the organisation’s vision.

- Infrastructure and resources. A management system and infrastructure capable of providing teams with the data, equipment, resources and permission needed to plan and deliver sustained improvement.

- Skills and workforce. A programme to build the skills and capability of staff across the organisation to lead and facilitate improvement work, such as expertise in quality improvement approaches and tools.

- Culture and environment. The presence of a supportive, collaborative and inclusive workplace culture and a learning climate in which teams have time and space for reflective thinking and feel psychologically safe to raise concerns and try out new ideas and approaches.

Underpinning these four elements is an improvement vision that is understood and supported at every level of the organisation. This vision is then realised through a coordinated programme of interventions aimed at improving the effectiveness, safety, efficiency, timeliness, person-centredness and equity of the organisation’s care processes, pathways and systems.

Q. Do we need a team of experts to lead quality improvement in our organisation?

A. Many large health care provider organisations, such as NHS trusts, have created a central improvement team to support front-line teams as they design and implement improvements to care processes and pathways, and to oversee organisation-wide improvement efforts. However, these organisations are not solely reliant on central teams’ expertise. They have also developed improvement capability at every organisational level, from the board downwards, so that all leaders, managers and front-line staff have an understanding of quality improvement approaches, methods and principles, and how to effect change in complex systems such as health care.

This is particularly important in smaller organisations, such as GP practices, that do not have the resources to recruit a dedicated improvement lead. Smaller organisations will also benefit from the opportunity to share improvement skills and learning within networks of professionals and organisations.

Q. Can quality improvement improve productivity and save money?

A. Quality improvement can improve patients’ experiences and outcomes, and produce financial and productivity benefits for the health care system.

Continuing with poor or sub-optimal care results in waste, and this creates unnecessary costs. For example, longer hospital stays for patients due to health care-acquired problems, such as infections or pressure ulcers, not only cause poorer health but add to costs. In this context, improving care can reduce the costs and boost productivity.

The potential for cost savings can be realised by addressing:

- delays, such as waiting lists for diagnostic tests

- reworking, in other words, performing the same task more than once

- overproduction, such as unnecessary tests

- unnecessary movement of materials or people

- defects, such as medication errors

- impaired morale caused by staff working in frustrating systems and cannot offer the best level of care.

In many cases, the capacity freed up from productivity gains made through quality improvement does not result in actual cash savings. Instead, this capacity is used to meet additional or previously unmet service demand.

When quality improvement leads to lower bank and agency staff costs, the reduction of procurement activity or the decommissioning of a fixed asset, it can produce cash savings that can be identified in annual financial reports. However, it is important, when calculating these savings, to include any costs incurred in the planning and implementation of the improvement.

To assess the return on investment from its application of quality improvement methods at scale, one health care provider, East London NHS Foundation Trust, has developed a framework with seven domains. As well as focusing on cost avoidance and reduction, it includes a domain on staff experience, highlighting evidence suggesting that providers with happier, more engaged staff have better patient outcomes and improved financial performance. The trust proposes that by giving front-line teams the autonomy to address the challenges that matter most to them and their patients, quality improvement plays a critical role in improving staff engagement and, in turn, the organisation’s overall performance.

Q. Why is there such a focus on variation in quality improvement?

A. Variation in health care can be warranted and unwarranted. This is because some degree of variation is considered normal, as it allows health services to be responsive and patient-centred.

Variation can be due to chance or random variation, for example, demand-side factors such as patient need and social demographics, or supply-side factors such as clinical practice. These can all lead to variations in inputs, processes and outcomes of care.

Unintentional deviation, or unwarranted variation from normal practice, is a form of variation in health care that can lead to inefficiency and waste. In clinical practice, variation from an established evidence-based best practice could result in error and harm, resulting in poor outcomes for the patient. Addressing unwarranted practice variation using quality improvement approaches and methods can increase the reliability of care.

Many quality improvement approaches assess whether a pathway, process or clinical practice is operating within control limits. These control limits are used as a key measurement tool to understand the level of variation in the system and to measure it over time. As well as being able to identify, measure and analyse variation, it is vital that health care systems, providers and commissioners have the necessary quality improvement capability, time and resources to address any unwarranted variation.

Q. What is the relationship between quality improvement and quality planning, control and assurance?

A. The approach taken by health care systems and organisations to manage quality usually consists of four interrelated elements:,

- Quality planning. Understanding the needs of the population and service users, for example, through equity needs assessments, and designing interventions to meet those needs.

- Quality control. Comparing the level of performance of a system or organisation against adopted standards or benchmarks that are locally developed and owned, such as quality dashboards and scoreboards, for the purposes of internal scrutiny and oversight.

- Quality assurance. Independently gathering evidence in a systematic and transparent way to provide confidence that a system is meeting internal or external standards, for example, through clinical audits, clinical incidence reports, staff surveys and external inspections of standards.

- Quality improvement. Using a systematic approach involving specific methods and tools to continuously improve the quality of care and outcomes for patients and service users.

The term ‘quality management system’ is sometimes used to describe the full cycle of planning, control, assurance and improvement that takes place in many health care systems, organisations and services. It is also a term used at a national policymaking level.

An understanding of when and how to use each of these four elements, and how to create an appropriate balance between them, is important. At national level, for example, it is important that quality assurance and control initiatives are complemented by sufficient support for quality improvement and planning at both a system and organisation level.

As well as the four elements listed, a quality management system requires a learning system. This includes processes for creating evidence, including evaluation to understand what is working for whom, and methods to identify and spread knowledge, such as learning networks. The effectiveness of a quality management system also relies on the presence of a set of behaviours, attitudes, relationships and skills that enable improvement.

Q. Can quality improvement contribute to environmental sustainability?

A. Environmental sustainability is a core dimension of the quality definition adopted by the NHS. The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare has developed a SusQI framework for integrating sustainability into quality improvement. This framework provides an approach where outcomes of service are measured against environmental, social and economic costs and impacts to determine value. Some examples of environmental issues that have been tackled through quality improvement include:

- staff and patient travel patterns, with a view to reducing the length and frequency of journeys and using more sustainable transport modes

- prescribing behaviours, for example, by promoting a switch to greener asthma inhalers

- procurement and consumption patterns, for example, by reducing paper use and purchasing recycled paper.

Q. How can successful quality improvement interventions be spread more widely?

A. In health care, a variety of mechanisms are used to spread improvement interventions. Social movements, such as professional networks and communities of practice, play an important role, as do organisational networks and collaborations. Quality improvement collaboratives are also used to spread successful innovations.

However, spreading an intervention that has worked well in one setting to other health care services, organisations or systems can be complicated, even if there is good evidence of its benefits. A key challenge is in identifying those aspects of the intervention that should remain fixed and others that can be adapted to fit each new setting. An intervention cannot simply be ‘lifted and shifted’ intact from one setting to another.

Each setting will present a different range of opportunities and barriers to implementation. In some settings, for example, cultural or professional beliefs and practices may impede its success and in other settings, strong support from an influential clinician or leader may generate an opportunity. In summary, spreading an intervention takes time and resources and needs careful planning.

Where can I find out more?

The following organisations provide information and case studies on quality improvement approaches, methods and principles.

Advancing Quality Alliance (Aqua)

A membership organisation within the NHS, providing quality improvement expertise, specialist learning and development and consultancy.

Centre for Sustainable Healthcare

A charity that is helping the NHS to fulfil its commitment to reduce its carbon footprint by 80% by 2050. They have developed a framework to support improving health care holistically, by assessing quality and value through the lens of its environmental, social and economic costs and impacts to determine its ’sustainable value‘.

https://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/susqi

East London NHS Foundation Trust

The trust has set up a quality improvement microsite offering a wide range of improvement resources and tools for front-line teams.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS)

A health body that hosts an improvement hub (ihub) bringing together expertise, knowledge and best practice to support health and social care organisations to redesign and continuously improve their services.

Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP)

An independent organisation led by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, the Royal College of Nursing and National Voices that aims to increase the impact of clinical audit on health care quality improvement.

Improvement Analytics Unit (IAU)

A partnership between NHS England and NHS Improvement and the Health Foundation that evaluates complex local initiatives in health care in order to support learning and improvement.

www.health.org.uk/improvement-analytics-unit

Improvement Cymru

The all-Wales improvement service for NHS Wales with expertise in developing, embedding and delivering system-wide improvements across health and social care.

https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/improvement-cymru

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)

A US-based independent not-for-profit organisation that seeks to improve health care worldwide through building the will for change, cultivating promising concepts for improving care and helping health care systems to put them into action.

International Society for Quality in Healthcare (ISQuA)

A membership-based organisation dedicated to improving the quality and safety of health care through education, knowledge sharing, external evaluation and its networks of health care professionals.

The King’s Fund

A UK charity that seeks to understand how the health system can be improved, and works with individuals and organisations to shape policy, transform services and bring about behavioural change.

www.kingsfund.org.uk/topics/quality-improvement

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

The institute has developed a set of practical resources for those looking to improve the quality of care and services using NICE guidance.

www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/into-practice

NHS England and NHS Improvement

The health body hosts an improvement hub that includes improvement tools, resources and ideas from across the health sector.

https://improvement.nhs.uk/improvement-hub

NHS Providers

The membership organisation for NHS hospital, mental health, community and ambulance services has developed resources on improving quality and safety at organisation level.

https://nhsproviders.org/topics/quality

NHS Quest

A member-convened network for NHS trusts that focus on improving quality and safety.

Q

A connected community working together to improve health and care quality across the UK and Ireland. It gives professionals and patients the opportunity to connect, share and learn through a range of activities, including special interest groups, Q visits and Q labs.

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP)

The college has set up QI Ready to support GPs and practice teams with quality improvement activities, including tools, guidance and case studies.

Royal College of Physicians Quality Improvement (RCPQI)

The college has developed resources, tools and courses to support clinicians and health care workers in their quality improvement work.

www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/rcp-quality-improvement-rcpqi

The external-facing quality improvement delivery arm of Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. It supports teams to redesign processes, practices and services using quality improvement methodology.

Sheffield Microsystem Coaching Academy (MCA)

The academy aims to help multidisciplinary front-line teams rethink and redesign services – for example, through the Flow Coaching Academy – and offers a range of improvement resources, guides and stories.

Social Care Institute for Excellence

An independent charity that aims to identify and spread knowledge about good practice to the large and diverse social care workforce and to support the delivery of transformed, personalised social care services.

The Healthcare Improvement Studies (THIS) Institute

The institute aims to strengthen the evidence base for improving the quality and safety of health care. It undertakes research projects to create high quality practical learning and leads a fellowship programme to build skills in improvement research across the UK.

References

- Berwick D. No needless framework. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2010.

- National Quality Board. A shared commitment to quality for those working in health and social care systems. Department of Health and Social Care; 2021 (www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-quality-board-shared-commitment-to-quality).

- Jones B, Horton T, Warburton W. The improvement journey. London: Health Foundation, 2019.

- Fulop N, Ramsey A. How organisations contribute to improving the quality of healthcare. BMJ 2019; 365:l1773.

- Jones L, Pomeroy L, Robert G, et al. How do hospital boards govern for quality improvement? A mixed methods study of 15 organisations in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26:978–86.

- Lucas B, Nacer H. The habits of an improver: thinking about learning for improvement in healthcare. London: Health Foundation, 2015.

- Mannion R, Davies H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ 2018;363:k4907.

- Kostal G, Shah A. Putting improvement in everyone’s hands: opening up healthcare improvement by simplifying, supporting and refocusing on core purpose. British Journal of Healthcare Management (online) 2021; 27(2).

- NHS Improvement. For more information on cause and effect (fishbone) diagrams see https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20200501112706/https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2093/cause-effect-fishbone.pdf

- NHS Improvement. For more information on driver diagrams see https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2109/driver-diagrams.pdf

- Public Health England. For an introduction to logic models see www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-in-health-and-well-being-overview/introduction-to-logic-models

- Shah A. Using data for improvement. BMJ 2019; 364:l189.

- Chassin M, Loeb J. High reliability healthcare: getting from here to there. Milbank Q 2013; 91(3):459–90.

- Dixon-Woods M, Martin G, Tarrant C, et al. Safer clinical systems evaluation findings. London: Health Foundation, 2014.

- Kaplan G, Patterson S, Ching J, et al. Why Lean doesn’t work for everyone. BMJ Qual Saf 2014; 23:970–73.

- Randall S. Using communications approaches to spread improvement. London: Health Foundation, 2016.

- Engle R, Lopez E, Gormley K, et al. What roles do middle managers play in implementation of innovative practices? Health Care Manage Rev 2017; 42:14–27.

- Palmer V, Weavell W, Callander R, et al. The participatory zeitgeist: an explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Med Humanit 2019; 45:247–57.

- Health Foundation. Person-centred care made simple: what everyone should know about person-centred care. London: Health Foundation, 2016.

- Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ quality and safety 2016; 25:509–17.

- Batalden P. Getting more health from healthcare: quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction. BMJ 2018; 362:k3617.

- Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:626–32.

- Renedo A, Marston C, Spyridonidis D, et al. Patient and public involvement in healthcare quality improvement: how organizations can help patients and professionals to collaborate. Public Management Review 2015;17:17–34

- Crisp H, Watt A, Jones B, Amevenu D, Warburton W. Improving flow along care pathways: Learning from the Flow Coaching Academy programme. London: Health Foundation, 2020.

- Liberati E, Tarrant C, Willars J, et al. How to be a very safe maternity unit: an ethnographic study. Soc Sci Med 2019; 223:64–72.

- Edmondson A. Teaming: How organizations learn, innovate and compete in the knowledge economy. San Francisco: Wiley, 2012.

- Greenhalgh T. How to implement evidence-based healthcare. Hoboken: Wiley, 2018.

- Ghosh A, Collins J. Skills for collaborative change. See https://qlabessays.health.org.uk/essay/skills-and-attitudes-for-collaborative-change

- Dixon-Woods M, Martin G. Does quality improvement improve quality? Future Hosp J 2016; 3(3): 191–4.

- Reed J, Card A. The problem with Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:147–52.

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement. See www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/qsir-plan-do-study-act.pdf

- Boland B. Quality improvement in mental health services. BJPsych Bull 2020; 44(1): 30–35.

- Smith I, Hicks C, McGovern T. Adapting Lean methods to facilitate stakeholder engagement and co-design in healthcare. BMJ 2020; 368:m35.

- Nelson E, Batalden P, Huber T, et al. Microsystems in health care: Part 1. Learning from high-performing front-line clinical units. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2002; 28:472–93.

- Godfrey M, Nelson D, Batalden P. Supporting microsystems. Assessing, diagnosing and treating your microsystem. 2010. See http://clinicalmicrosystem.org/knowledge-center/workbooks

- Mohr J, Batalden P. Improving safety on the front lines: the role of clinical microsystems. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11:45–50.

- Bate P, Robert G. Experience based design: from designing services around patients to co-designing services with patients. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15(5):307–10.

- Bate P, Robert G. Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: the concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. London: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007.

- Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Overcoming challenges to improving quality. London: Health Foundation, 2012.

- Dixon-Woods M. How to improve healthcare improvement—an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods. BMJ 2019; 367:l5514.

- Gabbay J, le May A, Connell C, Klein J. Skilled for improvement? Learning communities and the skills needed to improve care: an evaluation service development. London: Health Foundation, 2014.

- Gabbay J, le May A. Able to Improve? The skills and knowledge NHS front-line staff use to deliver quality improvement: findings from six case studies. London: Health Foundation, 2020.

- Lucas B, Nacer H. The habits of an improver. London: Health Foundation, 2014.

- Kaplan H, Provost L, Froehle C, Margolis P. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012; 21(1):13–20.

- Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, Testa L, Lamprell G. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open 2017; 7:e017708.

- Black N. Chief quality officers are essential for a brighter NHS future. Health Service Journal (online) 8 Oct, 2014. See www.hsj.co.uk/comment/chief-quality-officers-are-essential-for-a-brighter-nhs-future/5075497.article

- Shortell S, Blodgett J, Rundall T, Kralovec P. Use of lean and related transformational performance improvement systems in hospitals in the United States: results from a national survey. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018; 44:574–82.

- Jones B, Horton T, Warburton W. The improvement journey. London: Health Foundation, 2019.

- Marshall M, Øvretveit J. Can we save money by improving quality? BMJ Qual Saf 2011; 20:293–96.

- Shah A, Course S. Building the business case for quality improvement: a framework for evaluating return on investment. Future Healthc J 2018; 5(2):132–37.

- Dixon J, Street A, Allwood D. Productivity in the NHS: why it matters and what to do next. BMJ 2018; 363:k4301.

- East London NHS Foundation Trust. ELFT’s quality management system. See https://qi.elft.nhs.uk/elfts-quality-management-system

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. High Level Quality Management System Framework. 2019. See www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/previous_resources/policy_and_strategy/quality_management_system.aspx

- Shah A. How to move beyond quality improvement projects. BMJ 2020;370:m2319.

- Leatherman S, Gardner T, Molloy A, Martin S, Dixon J. Strategy to improve the quality of care in England. Future Hosp J 2016; 3(3):182–87.

- Albury D, Beresford T, Dew S, at al. Against the odds: Successfully scaling innovation in the NHS. London: Innovation Unit and Health Foundation, 2017.

- Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, et al. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Quality & Safety 2018; 27:226-240.

- Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. BMJ 2019; 365:l2068.

- Horton T, Warburton W. The spread challenge. How to support the successful uptake of innovations and improvements in health care. London: Health Foundation, 2018.