Forewordby Julia Unwin, CBE

Strategic adviser to Young people’s future health inquiry

In the UK today, young people face a complex mix of challenges as they navigate the path towards adulthood. At a time when there is more information and communication available to them than ever before, the opportunities they are offered and the challenges they face are ones that previous generations could only have imagined.

Major changes to the employment and housing markets mean that many young people face an insecure future, with the traditional milestones on the path to adulthood – such as leaving home or getting a secure job – simply inaccessible. Some young people may have the internal and external assets – for example skills, connections and support – to secure a healthy future. However, they face a constantly changing environment and it is whether their assets are sufficient to cope with this external world that makes the transition so difficult and, for some, so perilous.

This first report from the Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry describes the findings from a piece of engagement research, informed by direct conversations with young people around the UK. The findings make a compelling case for a fundamental change in how society supports this age group. Young people are our future. And yet for many, the path to adulthood fails to give them the stability they need to ensure it is a healthy one. This should worry us all.

The long-term health of this generation is one of our country’s greatest assets. In some aspects of young people’s health we have made great progress. But these gains may be temporary, as their current experiences erode their mental health and future health prospects. This presents a major problem for policy makers, who have to plan for an increasingly uncertain future.

Ignoring this challenge will cost us all dear.

Introduction

Between the ages of 12 and 24, young people go through life-defining experiences and changes. During this time, most will aim to move through education into employment, become independent and leave home. This is also a time for forging key relationships and lifelong connections with friends, family and community.

These milestones have been largely the same across generations. But today’s young people face opportunities and challenges that are very different to those experienced by their parents and carers, and from those they imagined themselves to be facing during their teenage years.

This matters because these building blocks – a place to call home, secure and rewarding work, and supportive relationships with their friends, family and community – are the foundations of a healthy life. There is strong evidence that health inequalities are largely determined by inequalities in these areas – the social determinants of health. So while young people are preparing for adult life, they are also building the foundations for their future health.

Young people’s future health isn’t simply their own concern, it is also one of society’s most valuable assets.

About the inquiry

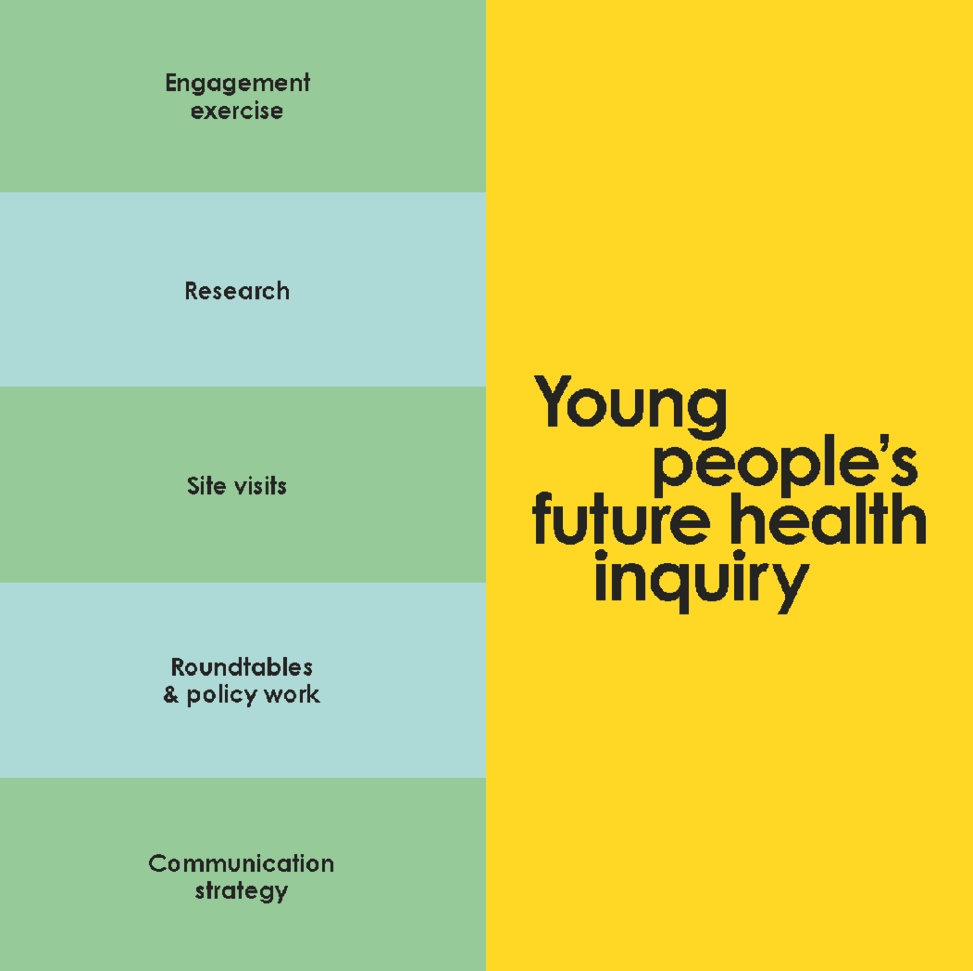

The Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry is a first-of-its-kind research and engagement project that aims to build an understanding of the influences affecting the future health of young people.

The two-year inquiry, which began in 2017 aims to discover:

- whether young people currently have the building blocks for a healthy future

- what support and opportunities young people need to secure them

- the main issues that young people face as they become adults

- what this means for their future health and for society more generally.

Alongside the engagement work with young people, the inquiry involves site visits in locations across the UK, as well as a research programme run by the Association for Young People’s Health and the UCL Institute of Child Health. The inquiry will culminate in a policy analysis and development of recommendations in 2019.

The engagement exercise

This first report in the inquiry shares the findings from our engagement work. The Health Foundation commissioned Kantar Public, an independent social research agency, which partnered with Livity, a youth engagement specialist, to conduct an engagement exercise with young people living in the UK aged 22–26. The aim was to discover the factors that helped or hindered them in their transition to adulthood.

The engagement exercise adopted a mixed method and iterative research approach, which incorporated both qualitative and quantitative research methods. See Appendix 1 for more detail on the methodology.

The Health Foundation also commissioned Opinion Matters, an insight and market research agency, to conduct an online survey of 2,000 young people aged 22–26 and gather their views on the challenges they are facing that could impact on their future health.

Main findings — at a glance

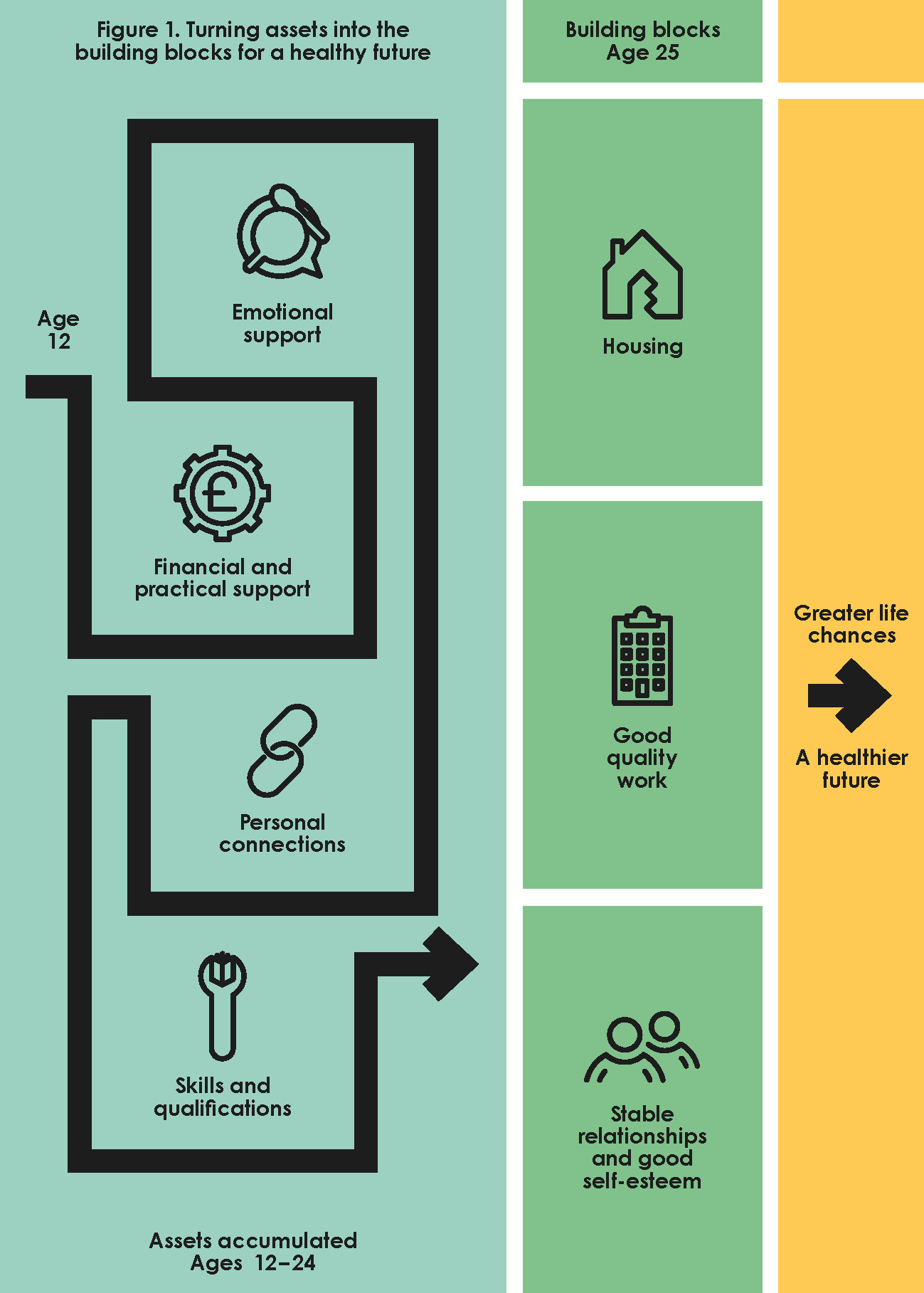

When discussing what helped or hindered them in their transition to adulthood, young people identified four assets that were central to determining their current life experiences.

Appropriate skills and qualifications:

whether young people had acquired the academic or technical qualifications needed to pursue their preferred career.

Personal connections:

whether young people had confidence in themselves, along with whether they had access to social networks or mentors who were able to offer them appropriate advice and guidance on navigating the adult world.

Financial and practical support:

this could be direct financial support from their parents, being able to live at home at no cost with parents, as well as practical assistance such as help with childcare.

Emotional support:

having someone to talk to and be open and honest with, who supports their goals in life. This could include parents, partners and friends as well as mentors.

The engagement work showed that not all young people had these assets. The presence or absence of these assets led to particular patterns of experience with certain experiences reinforcing each other and a number of broad groups emerging.

The young people who typified these groups were already, by their mid-20s, experiencing very different circumstances from each other in terms of their ability to secure a good home and employment, and build and maintain stable relationships with friends and family. Thus, it is likely that they will face different long-term health prospects.

From 12 to 24 – a time to build a healthy future

The health of future generations is not only essential for individual wellbeing. It is also one of society’s most valuable assets. Wellbeing and health are important foundations of a good life for the individual and for a strong society.

A time of transition

Latest census data show that there are around 10.5 million young people aged between 12 and 24 living in the UK, representing almost one in five of the population. Research shows that during this time of their life, young people go through an intensive period of physical and brain development. Current thinking in neuroscience suggests that young people’s brains are still developing into their 20s meaning experiences during this period are likely to be influential throughout their lives.

Moving from childhood to adulthood involves a series of life-changing transitions. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the following key changes that typically occur during this period:

- transition out of school

- transition into the workforce

- transition from a family home

- transitions to taking responsibility, for example taking responsibility for their own health.

‘The accumulated evidence demonstrates that investing in [young people] provides our best hope of breaking the intergenerational cycle of poverty and inequity that weaken communities and countries and imperils the development and rights of countless children.’ – UNICEF

The transitions young people are experiencing are happening alongside huge shifts in the economy, society and technology. From housing to education and the labour market, and from family structures and digital engagement to community networks, society is changing in ways that will have a significant and lasting impact on today’s young people.

In addition, some young people will face particular challenges. Gender, ethnicity, sexuality, disability and numerous other factors will affect how a young person transitions into adulthood and the experiences they have.

A recent Lancet Commission report highlights that the period from 12 to 24 years can be a time for a ‘second chance’, where any disadvantages that young people may have faced in earlier life can potentially be reduced or even reversed. However, findings from the engagement work suggests that this opportunity is not being taken and as a consequence many young people are unable to secure the building blocks needed to create a healthy future.

By exploring and raising awareness of the issues that young people face as they move into adulthood, this inquiry aims to discover what young people need for a healthy future and what needs to be done now to maximise their health in years to come.

When people talk about health, they tend to focus on issues concerning services and treatments. But we know that there are other factors that help create good health and wellbeing that have little to do with our ability to visit our local GP or hospital. Creating the conditions that promote good long-term health and wellbeing throughout adult life goes well beyond the reach of the NHS – the combined effects of education, employment, housing, relationships with family and community play a greater part. These factors are known as the social determinants of health.

The social determinants of health

The term ‘social determinants of health’ describes the social, cultural, political, economic, commercial and environmental factors that shape the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.

The inquiry takes a social determinants approach to understanding young people’s future health prospects. This points to the need to act early in life to increase a young person’s chance of enjoying a healthy future. The inquiry recognises that the factors that affect an individual’s health over their lifetime, such as level of education and income, strength of relationships and self-esteem, and links into housing and community, are uniquely shaped between the ages of 12 and 24. What young people learn and experience during this period will affect the rest of their lives.

There has been significant action on the broad range of social support needed during the early years of life from 0 to 5 to improve life chances. But far less is known about the support needed during the 12–24-year window to increase young people’s opportunity for a healthy life.

Where research does focus on this age group, it tends to do so on one or two factors:

- external environmental factors, such as labour and housing market issues, and the demographics of the local area

- factors specific to the young person, such as resilience and self-esteem.

Rather than seeing these as entirely separate, the inquiry recognises the need to understand both sets of factors, as well as the interactions between the two. This requires us to consider young people’s experiences and their implications for their wellbeing and health holistically rather than looking at specific issues in isolation. However, there are limitations to this approach. Treating young people as a cohort means that there is a lack of emphasis on specific factors which define individual experience, such as gender, ethnicity, sexuality and other areas, indicating a need for further exploration.

The inquiry aims to understand the extent to which young people have the building blocks to create the foundation for a healthy life – broadly:

- home: access to secure, affordable housing

- work: the potential to engage in good quality work

- friends: a network of stable relationships and good self-esteem.

The focus is on these three building blocks as they are some of the key foundations determined in this age group. It seems likely that the interactions between external environmental factors and factors specific to the young people were likely to come into focus in these areas, and that these three building blocks would have an impact on the other social determinants of health. It also seems likely that these areas could be amenable to policy change or local interventions.

Each of these building blocks is explained in the following pages.

Home

A safe and secure home environment is an essential building block for a healthy future. Overcrowded housing increases the risk of accidents, respiratory and infectious diseases, and adults in poor housing are 26% more likely to report low mental health. In the past five years, one in five adults has experienced issues such as long-term stress, anxiety and depression due to a housing problem.

The crowded nest

Young people are staying in their parents/carers’ homes for longer than ever before. It is expected that within a decade almost 50% of young adults will live with their parents/carers. In 2016, almost half (46%) of young people aged 22 to 24 were living with their parents/carers – an increase from 39% in 2009. While young people who are able to do this often find themselves in a better position than their peers financially, this may also affect their sense of independence, as well as their relationships with their families and peers. Research also suggests that parents/carers’ quality of life decreases when older children return to the family home after a period of living away.

86% of 22–26-year-olds agree that most young people today can’t afford to move out of home

Source: Opinion Matters poll conducted for the Health Foundation

Generation rent

Young people today are much less likely than their parents/carers to own their own home. Those who do manage to fly the nest are likely to be living in the private rental sector, with four out of ten 30-year-olds living in rented accommodation. This shift away from ownership has been significant and fast. It is also expensive. Millennials (born between 1981 and 2000) spend almost a quarter (23%) of their income on housing, highlighting an increase from the 17% spent by baby boomers (born between 1954 and 1964) at the same age.

As well as spending more of their income on housing than previous generations, millennials are also more likely to live in overcrowded conditions. Along with the link to accidents and disease mentioned earlier, there is a link between overcrowding and mental ill health as a result of stress, tension, family break-ups, anxiety and depression, and chaotic and disturbed sleeping arrangements: all potential outcomes of living with too many people in unsafe conditions.

Alongside the cost of housing, security of housing is also an issue. Of private renters in England, 29% have moved at least three times over the last five years (this figure increases to 37% in London), and moving is in itself costly. It is also likely that frequent moves are not a choice people are making freely. According to a recent survey, two-thirds of private renters would prefer to own their own home and a further 10% would prefer to be in social housing. It is likely that this reflects as much of a desire for greater security as for home ownership in itself. While housing costs remain so high, neither renting on an insecure tenancy or buying if repayments are unaffordable provide the security necessary for long-term health.

Homelessness

Homelessness has a significant impact on the long-term health and wellbeing of young people. It can lead to exhaustion and feeling at risk, as well as producing barriers to education and jobs, which take a serious toll on young people’s physical and mental health. Due to its complex nature, it is difficult to gain a clear picture of the extent of youth homelessness, but it is a growing concern. One poll of 2,000 16–25-year-olds found that one in five had to ‘sofa surf’ in 2014 because they had nowhere else to go. Approximately half of these sofa surfed for over a month.

4 in 10 people in their thirties are living in private rental properties today ... compared to only 1 in 10 people of the same age 50 years ago.

In the 16–25 age range, 1 in 5 had to sofa surf in 2014 because they had nowhere else to go, with half sofa surfing for over a month.

Some groups are more disadvantaged than others. For example, young lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people make up almost a quarter (24%) of the youth homeless population.

Work

Good quality work is associated with better health than unemployment or insecure employment. Unemployment can result in lower living standards, in turn triggering distress and encouraging unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking and alcohol consumption. Research by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at the UCL Institute of Education found that unemployed young people are more than twice as likely to suffer from mental ill health compared to those in work.

On top of this, the quality of work is another crucial element to health: low paid and unstable jobs, dangerous working conditions, hard physical labour and long or irregular hours can all have a negative impact on health.

Our young people’s poll found: 53% of people aged 22–26 said that it was difficult for young people generally to find secure fairly paid work that has scope for career growth and development.

The under-employed generation

Youth unemployment can have serious long-term effects on future employability and wages, and therefore on long-term living standards and health. Research shows periods out of work can cause ‘scarring’ effects for young men especially, whereby their earnings and employment chances are still affected years later.

Although there may be positive benefits from the trend of lower unemployment, there is widening concern that those who do find jobs are potentially at more of a disadvantage than other age groups due to poor pay and the quality of work found.

The Resolution Foundation has warned that millennials are at risk of becoming the first generation to earn less than their predecessors, with findings suggesting that this group have earned £8,000 less throughout their 20s than the generation before them (born 1966–1980). These low earnings at what is usually a time of career progression could leave millennials with lower lifetime earnings than previous generations.

Young people are also more likely than any other age group to be on zero-hours contracts, making up a third (33.8%) of this new workforce. Zero-hours contracts can provide flexibility for workers and are indeed enjoyed by some young people. However, in the long-term they can negatively impact on people’s health and wellbeing. Recent research has found that at the age of 25, people on zero-hours contracts were less likely to report feeling healthy than those in more secure work and reported more symptoms of psychological distress. For young people without any financial safety net, this way of working can be highly stressful in the long term.

Higher education

Young people today are more likely to go to university than ever before, with half of all young people in England expected to receive a university education. Cost still dominates public discussion about university education, with a recent study showing that half of those surveyed were worried about the combined cost of tuition, student loans and the cost of living.

In addition, almost half (49%) of recent graduates are working in ‘non-graduate’ roles, and 28% working young people feel trapped in a cycle of jobs they do not want, with 29% saying they have to take whatever work they can, instead of focusing on their career.

It is uncertain what this situation means for these young people’s health. Higher levels of education have been associated with better future health. However, as the complex relationships between education, income and opportunity change, it is unknown whether highly educated individuals who have few opportunities and low incomes will continue to experience the same strong health prospects.

Alongside rising numbers of university students, there has been a fall in the number of people entering apprenticeships since the introduction of the Apprenticeship Levy and the changes in funding. The apprenticeships that are on offer today tend to be taken up by young people from wealthier families, leaving those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds with fewer opportunities. There are other vocational and technical options that exist for young people, but these are taken less often and may be less visible.

Pakistani and Bangladeshi graduates are about 12% less likely to be in work than white British graduates ... Indian and black Caribbean graduates are about 5% less likely.

Friends

Social networks are important to our health. Good relationships with friends, family and peers allow people to feel supported and enable them to develop skills and good levels of self-esteem and resilience when facing new situations. Social isolation, living alone and loneliness are linked with an approximate 30% higher risk of early death.

Our young people’s poll found: Of people aged 22–26, 18% said it was difficult for young people to build happy and fulfilling relationships with family, friends and partners.

Of people aged 22–26, 80% agreed that young people today are under pressure to appear or behave in a certain way on social media.

Changing relationships

Consistent with polling for this report, Relate also found that four out of five young people said they had good relationships with their friends. However, it is concerning that a large minority do not report good relationships. In addition, the proportion of young people who feel they have someone to rely on has decreased in recent years.

With the mandatory age for education increased to 18, and with more young people going on to higher education, the contexts in which they are spending their time are changing. Young people today are spending longer periods of time mixing largely with their peer group rather than with others of different ages.

Young people today have grown up alongside developing technology. This means they are the first generation to learn to navigate the tricky social waters of friendship and romantic relationships from behind a screen. This represents a major change, and any consideration of young people’s transition to adulthood needs to recognise that some of the effects of this are as yet unknown. While the impact of social media on health is debated, a Royal Society of Public Health report found that all platforms had a negative impact on sleep.

Mental health and loneliness

More young people than ever are reporting mental health issues, such as anxiety or depression, with figures rising to 21% in 2013 – 2014. In particular, there are large numbers of young women reporting symptoms of mental health problems. In 2014–2015, around one in four young women (25%) reported symptoms of anxiety or depression compared with fewer than one in six young men (15%). However, attitudinal research suggests men are far less likely to report their own experiences of mental health problems and are less likely to discuss mental health problems with a professional. Suicide is the leading cause of death in men under the age of 45.

65% of young people aged 16–24 said they felt lonely at least some of the time and almost a third (32%) felt lonely ‘often or all the time’. This compares to 32% of people aged 65+ feeling lonely ‘at least some of the time’.

Where relationships with parents are poor and teenagers are neglected by them there can be significant problems including with mental ill health, substance misuse, and issues with school attendance, behaviour and attainment.

Two-thirds of gay, lesbian and bisexual secondary school children were found to have experienced homophobic bullying.

A number of children from ethnic minority groups also report racially motivated bullying and harassment.

The findings

Our engagement work with young people found a gap between what their expectations as teenagers had been of their life in their twenties and their actual experiences. As teenagers, they had expected, by their mid-twenties to have a secure job, own a home and be married or in a secure relationship, often with children. A vision largely driven by what they imagined their parents’ lives to have been like at that age.

However, by their twenties few, if any, of these expectations had materialised. Young people were generally struggling to secure permanent work with the salaries, conditions and work-life balance they wanted – underemployment and insecure work were commonly mentioned as a source of anxiety. Few yet owned their own homes – something they perceived as a source of security. Yet their aspirations still remained largely unchanged. They continued to work towards the same goals, striving to make up the gap between expectations and reality.

Not yet feeling like adults, but no longer teenagers, young people characterised their twenties as a kind of liminal phase – caught between these two identities. In the face of having accomplished less than they had expected, this transitional period was often dominated by stress, insecurity, and anxiety – as young people struggled to live up to their own expectations. As a result, priorities for this group were driven by a desire for stability, security, and a sense of control.

Throughout these discussions, four assets consistently emerged as important in helping young people secure the building blocks for a healthy future.

We listened to young people’s experiences in Cardiff, Glasgow, Leeds, London and Newtownabbey in Northern Ireland. More information on the voices of young people can be found in the appendix.

The four assets are as follows.

- Appropriate skills and qualifications: ‘how right are my skills for the career I want?’

- Personal connections: ‘the confidence and connections to navigate the adult world’

- Financial and practical support: ‘having the support to achieve what I want from life’

- Emotional support: ‘people I can lean on emotionally’

Each of these is explained in the following section.

Appropriate skills and qualifications

What young people said

A big consideration for young people was whether they had obtained or were on their way to obtaining the right skills and qualifications to get the career they wanted. This was not about what level of education they had, but about whether they had the appropriate skills to pursue their chosen career whether they wanted to be an electrician, solicitor or actor.

Our young people’s poll found: While most (92%) young people think it’s important to have the opportunity to achieve the right skills and qualifications for their chosen careers ... less than half believed they fully had the opportunity to achieve these skills and qualifications.

Some young people struggled to decide what they wanted to do and, more commonly, they found that the skills they did have were not the ones they needed for their preferred job.

‘My difficulties used to lie in the fact I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, so I always doubted myself.’

Cardiff

Young people also identified pressure to pursue a certain path, due to their parents’ expectations or professions, as a reason for selecting a career that was not their first choice.

‘Sometimes you cannot talk to your family, they think things are so rigid, but they’re not. It’s different when you grow up in this lifestyle, this culture.’

London

What others are saying

Ensuring that young people have the right skills for employment is also of increasing concern for employers. The British Chambers of Commerce identifies skills shortage as the biggest risk for business. Its January 2018 Quarterly Economic Survey revealed that of the manufacturers that had attempted to recruit in the last three months (66%), 75% had difficulties recruiting. Skilled manual labour was the key area lacking among applicants (68%). Similarly, in the services sector, 71% of businesses attempting to recruit said they had experienced greater recruitment difficulties. For both sectors, these figures indicate the highest level of reported recruitment difficulties since records began.

The Prince’s Trust Youth Index recently found that 28% of working young people felt trapped in a cycle of jobs they did not want. Furthermore, 29% of working young people said that they had to take whatever jobs they could, instead of focusing on their career.

Personal connections

What young people said

Young people highlighted the importance of having personal connections who could help when it came to employment. These provided them with:

Advice:

Guidance through the job market, helping them identify what they wanted to do, the skills needed and how they get there.

Networks:

Connections to networks that could unlock the door to finding a job or help them take their first step on the career ladder.

Confidence:

Support to boost their confidence in their ability to achieve their goals. This is particularly important when applying for jobs and being able to handle new situations, especially in the workplace.

Our young people’s poll found: Of people aged 22–26, 89% said that having the right relationships and networking opportunities to help them enter and progress through the working environment is important ... but just 31% felt they fully had these growing up.

Young people often mentioned parents/carers and other family members as providing advice and networks to help them get their first job. They also described mentors – both formal and informal – as providing support, filling gaps left by parents/carers who lacked relevant experience, who were unsupportive or who were not around. For some young people, these connections were fundamental to them starting their careers. Even for those who were highly qualified (eg in law or teaching), a lack of personal connections meant they struggled to step onto the career ladder.

‘I am in such a competitive industry and this is something I definitely didn’t realise before studying it at university. Therefore, the challenges I might face along the way are other people trying to achieve the same as me. Any available work experience in related companies would hopefully help me achieve a career.’

Newtownabbey

Young people saw self-confidence as important. Certain personal connections helped boost their confidence. Many saw success as a result of their own hard work and attributed failure to a lack of confidence. Some people found having a ‘personal cheerleader’ invaluable in helping them take the necessary steps to get where they wanted.

‘When I went back to studying after having my girl, my lecturer was really, really encouraging to me in helping me get through. He’s done so much personally for me… I thought I would never be able to do this [go back to studying].’

Glasgow

What others are saying

Research also indicates a direct relationship between personal connections and the job market. According to the Next Steps survey, at 19 years old, 20% of those who were previously NEET cited friends and family as a factor that helped them into employment. This and ‘own motivation’ were the most popular factors.

In addition, research by the Education and Employers charity found that the more encounters young people had with employers while in school, the more they are likely to earn and the lower their chances are of finding themselves NEET as young adults.

Relationships and social capital are not just about knowing people who can help find you a job. They are also about providing the ‘know-how’ to thrive in the working world. The Prince’s Trust refers to this as ‘the social bank of mum and dad’, with young people from more affluent families more likely to have help with writing a CV, filling out an application, preparing for an interview or finding work experience.

The Prince’s Trust found that 44% of young people from poorer backgrounds said they did not know anyone who could help them find a job. This compares to 26% of their more advantaged peers. Supporting these figures, 20% of young people found some work experience through parents/carers, but only 10% of those from poorer backgrounds said they found similar opportunities.

Financial and practical support

What young people said

Young people spoke a lot about ensuring they had the right help. This help was broadly split into two categories:

- practical support, such as childcare or the continued ability to live at home with their parents/carers

- financial support for things like rent and bills.

Young people saw the need for this safety net as particularly important as they transitioned into adulthood.

‘I love that my mum and dad are there for me … it gives me the opportunity to save my money instead of wasting it on rent.’

Cardiff

Our young people’s poll found: Over three-quarters (77%) of people aged 22–26 said that having financial and practical support from family was important ... but less than half (46%) felt they fully had these growing up.

Those who lacked a strong safety net found housing experiences particularly stressful. Many were expected to move out of the family home at the end of school or university, or reached a point where their parents/carers did not have the space for them. In some cases, this resulted in young people relying on benefits and low-cost housing, which sometimes led to inadequate living situations.

Lack of a safety net – for example being able to live at home rent-free or support with childcare – limited their ability to take risks such as changing career paths or returning to work after having a baby.

Parents/carers appeared to be the primary provider of this safety net. Some young people, especially those from more affluent backgrounds, suggested that their parents/carers would also cover, or contribute to, their bills and rent while they were at university or after moving out of the family home.

‘I can only afford it through class privilege. I 100% do not currently have the income to pay for this flat.’

Newtownabbey

What others are saying

Findings from the Resolution Foundation’s Intergenerational Commission suggests that millennials (born 1981–2000) are at risk of becoming the first generation to earn less than their predecessors. As pointed out earlier, its findings suggest that millennials (born 1981–2000) have earned £8,000 less throughout their 20s than the generation before them (born 1966–980).55 If this trend continues it will only further young people’s financial dependence on their parents/carers, increasing the division between those who have a practical and financial safety net and those who do not. With rising costs and stagnating wages, the debt to income ratio for 17–24-year-olds in 2015 was 70%, compared to 34% for 25–29-year-olds and 11% for 60–64-year-olds.

Emotional support

What young people said

Emotional support also emerged as a necessary asset during transition to adulthood. This support mostly came from parents/carers and partners, but in some cases came from other family members, mentors (teachers, community members, work managers) or friends. Young people placed significant importance on being able to speak openly and honestly about their future and in return they wanted to receive encouragement to take the risks that would help them achieve what they wanted, such as going back to education or retraining. Where young people were in stable relationships, partners in particular played a key role in supporting some of the young people’s ambitions, while encouraging them to pursue their desired career path.

Our young people’s poll found: Of people aged 22–26, 90% said that having emotional support from family is important ... but less than half (49%) felt that they fully had this growing up.

In some cases, when young people had fractured relationships with their parents/carers, friends provided them with emotional support, helping them get through difficult periods in their lives such as mental health issues, relationship breakdowns and bereavements.

‘My friends have an important role in my life, when I have problems they help me through and help me solve them… when we have a break, as in nights out, they’re the best to make your night fun and create good memories.’

Glasgow

Having strong emotional support was not a universal experience. Some young people lacked it in any form as they had unhealthy or fractured relationships with their parents/carers, partners or friends and no access to any additional support such as a mentor. In other cases, some young people had very supportive families but felt isolated from them as they had moved away for work or university. This meant these young people had limited access to much-needed emotional support.

What others are saying

The existing academic research suggests a complex interplay between emotional support, relationships, wellbeing and long-term health. These factors exist in cyclical relationships, influencing and exacerbating one another. The research also reflects the fact that young people need to develop social and emotional capabilities as well cognitive skills to achieve the outcomes they value and that they often do this by modelling the examples they see around them.

Recent developments in neuroscience for this age group have revealed that emotional processing and emotional regulation are continually developing during the teenage years. While understanding is continually developing, it is likely that strong emotional support during this period can help young people learn to manage their emotions constructively. Indeed, there is evidence that having a ‘trusted adult’ providing support in a young person’s life can mitigate some of the impacts of abuse and other adverse experiences of childhood.

The outside world

What young people said

As well as the four assets identified above, young people discussed the impact their environment was having on their ability to achieve their goals. They talked about the challenges in getting a job due to a lack of opportunities in their local community, leaving some feeling trapped and at a ‘dead end’. In some cases, this was compounded for young people in areas with a difficult housing market, with soaring rents and poor quality housing.

Despite these factors being beyond their control, many young people still felt that the resulting challenges were due to their own lack of confidence, laziness or poor financial management. Some carried a very strong sense of personal responsibility for their successes and their failures, with a clear affect on their self-esteem. At the same time, young people who were achieving what they wanted felt that their success came from their own hard work and determination.

‘I’ve had four different jobs, only one of them was full time, but I was self-employed… There isn’t enough full time jobs for people.’

Cardiff

‘House prices are really expensive and out of the realm of what you can afford.’

Newtonabbey

What others are saying

The levels of youth unemployment vary across the country. Particularly in areas that once relied on traditional industries such as coal mining or manufacturing, as well as seaside areas. In the UK, Middlesbrough, Stockton, Barnsley and Glasgow have the highest rates of youth unemployment, with Southampton, York and Reading and Bracknell experiencing the lowest.

The price and quality of housing also varies significantly across the country, alongside a varying relationship with local wages, creating a complicated system to navigate for young people when looking for work outside their local area.

The outside influences working against young people are not limited to the local job and housing markets. Other factors such as community cohesion and whether there are clear pathways from education and training into the workforce will also have an impact on the extent to which young people are able to develop assets as they grow up and realise value from them as they transition into adulthood. Recent policy changes, such as the introduction of universal credit, and the age cap on the living wage, also affect young people as they transition out of education and their parents/carers home into the working world. The traditional safety net provided by the benefit system, that in the past has helped people cope with periods of disadvantage, is becoming weaker. A four-year freeze to most working-age benefits is reducing their value relative to the cost of living. In 2018–2019 alone this equates to a 3% real-term cut. Universal credit is overall less generous than the system it replaces and it is the under-25 single parent families who are expected to lose the most.

‘The fact is that the conditions to which we are exposed influence our behaviour. Most of us cherish the notion of free choice, but our choices are constrained by the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age.’

Michael Marmot, The Health Gap

Young people: Do they have the mix of assets they need for a healthy future?

The extent to which a young person has the opportunity to develop the four key assets (skills, personal connections, practical/financial support and emotional support), and how these mix and interact will affect the extent to which they are able to secure the building blocks for a healthy life (a home, work and friends).

Furthermore, it is not simply the immediate experiences that matter but also how these interact with the wider environment in which young people live, such as the local housing and labour markets.

In the analysis phase, it emerged that young people’s situations tended to cluster into four broad groups that have a range of shared characteristics. These groups are fluid. An individual could be in one group at a certain point in their early adulthood, then move into another if their circumstances change.

As part of the engagement exercise, Livity worked with young people to help them describe these groups in their own words. These are the descriptions used below.

The case studies here are based on experiences shared during the workshops. However, to protect the anonymity of the young people involved, they are composites developed in conjunction with the young people at Livity.

The four groups are:

- Starting ahead and staying ahead.

- It’s not what you know, it’s who you know.

- Getting better together.

- Struggling without a safety net.

Figure 1. Turning assets into the building blocks for a healthy future

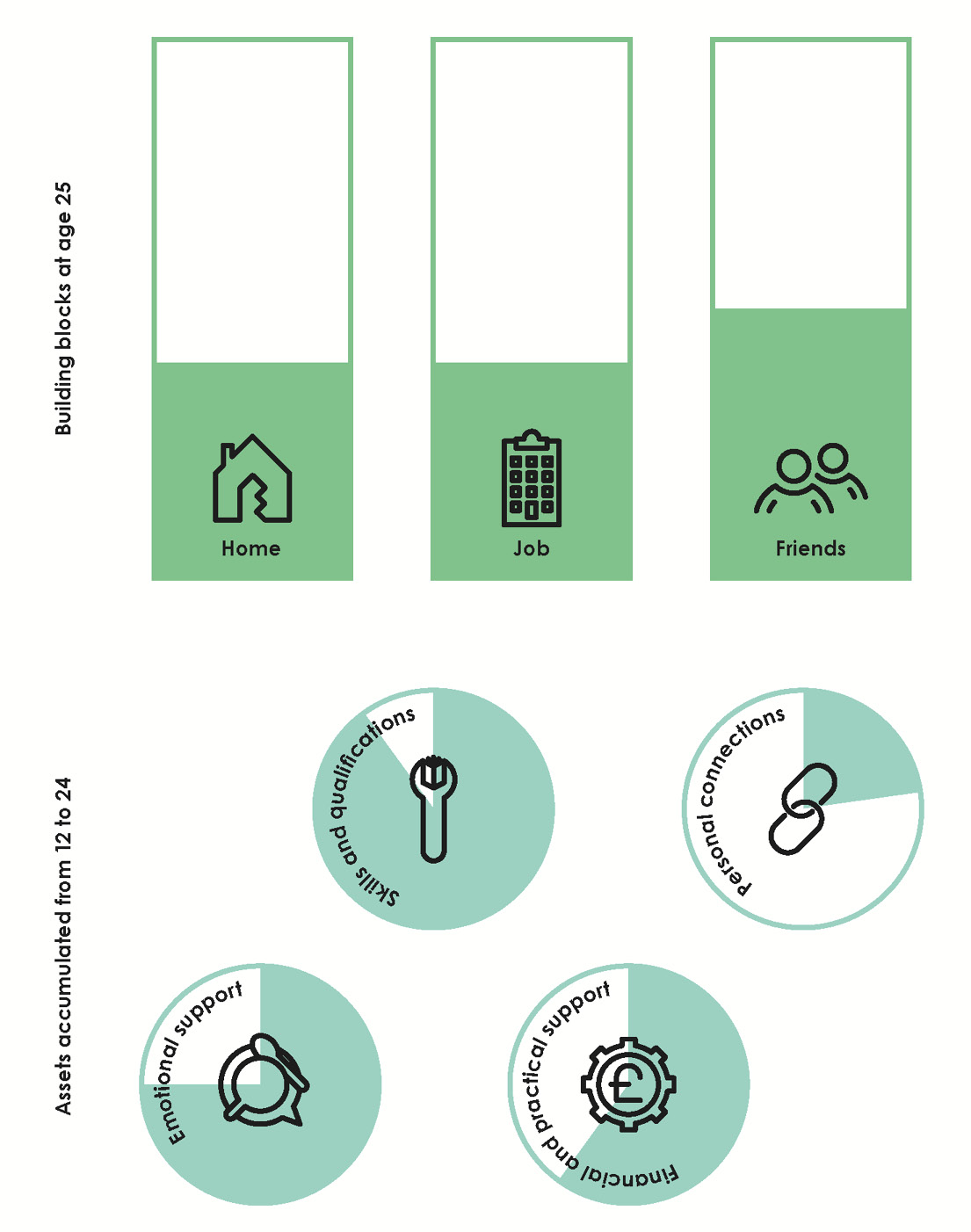

Starting ahead and staying ahead

Young people in this group said that they had the opportunity to develop all four assets. They had:

- the skills needed for their desired career

- strong connections with peers that helped them get their first job, with opportunities to develop

- a safety net of emotional, financial and practical support thanks to strong relationships with their family and/or partner.

On the whole, the majority came from more affluent backgrounds, in turn giving them more of a chance of accessing these four things.

As a result, these young people felt they were able to take more risks, such as changing career or retraining, especially when compared to young people from less affluent backgrounds who lacked the same financial and practical security. Due to the support they had, young people in this group more readily trusted people, institutions, organisations and government, and were less likely to have had a negative experience of them. This was because external factors such as a difficult job market were less likely to have had a harmful effect on their lives.

However, things were not always perfect. These young people sometimes struggled to deal with the pressure to meet high expectations set by themselves and others. As they had less exposure to life’s hardships, they struggled with anxiety and with knowing how to deal with challenges.

Figure 2. Starting ahead and staying ahead: How will the mix of assets shape the building blocks for a healthy future?

‘We have joint goals in life and I feel I have support with anything. He’s probably the reason I am overall very happy in life’

Leeds

‘I love my job, I love learning new things every day and there is a lot of room for progression. It also allows me to live a happy work- life balance’

Glasgow

Lara, 24, Glasgow

‘I work in a Glasgow accounting firm and I love it. It wasn’t what I had expected to end up doing as I’d always planned to go to uni and then become a teacher after my gap year. But after school I landed an accounting job to earn a bit of money and ended up falling in love with it. When they offered me a permanent position it was easy to say yes, and now I’ve been promoted and am studying for further qualifications.

‘Even though I’m 24 I love still living at home especially as I’m really close to my parents. They’re the most important people in my life, alongside my partner. We’re currently saving to buy our first house – I can’t wait for us to build our lives together in a place of our own. I’d like to find somewhere close to where we are now so I can still drop in on my family, especially once we get engaged and start a family. But before that all starts we want to go travelling. Asia is our dream destination but we’re holding off until we’ve got our first home – that’s the priority.’

It’s not what you know, it’s who you know

The young people in this group had the skills but lacked the connections needed to turn them into a job in their chosen career. Despite doing well at school and achieving the right qualifications, they struggled to overcome factors outside their control, such as a competitive job market or lack of opportunities in their local area. Tending to come from less affluent backgrounds, they were often the first person in their family to go to university, meaning there was no one to provide the advice or connections they needed.

Many worried about ‘failing’ and not meeting their own or their family’s expectations, and had higher levels of self-doubt and lower resilience, sometimes stemming from job application rejections. They often felt let down and misled, as if they were meant for greater things in life. Having sustained frequent knocks to their confidence, they were left struggling to feel they had any control over their futures.

Some young people in this group had moved to new areas and out of home in order to get a job they really wanted. However, this meant they had less financial and practical support in the local area. This put them at higher risk of ending up in debt, as they turned to loans to supplement their income while they secured a job. For some, the level of debt had become uncontrollable, leading them to transition into another group such as ‘getting better together’ or ‘struggling without a safety net’ (described below).

Figure 3. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know: How will the mix of assets shape the building blocks for a healthy future?

‘In the office [housing charity] everyone is basically the same… they all went to uni and sometimes the same uni… and I get the feeling they haven’t ever met someone like me before, they haven’t got a clue about the people’s lives that they’re trying to help.’

Leeds

‘I graduated from university and I am now working part-time in retail while I look for other jobs. I don’t find it fulfilling. I am confused as I don’t really know what jobs I should be looking for.’

Leeds

Mary, 26, Newtonabbey

‘I’m currently temping doing admin at a local authority in the social care team. It’s only a six-month contract covering someone on maternity leave. I’m pretty frustrated as this is not what I want to be doing. I worked hard at school, and have a teaching qualification from Belfast. I had thought teaching would be a safe bet leading to a good, stable job with a steady salary.

‘After I finished uni, I moved back in with my parents and started applying for as many training positions as I could find. There were some interviews but nothing really worked out. I even applied for roles in the Civil Service but didn’t pass the assessment centre. I don’t know why all my hard work isn’t paying off, especially when some of my friends from uni are getting jobs elsewhere. My parents are there for me but they don’t know anyone in teaching who could help me out. I do appreciate that they’re letting me live at home but it is pretty lonely and I get quite bored.

‘The admin job was a last resort really because I needed some money to support myself and contribute to the household bills. I’m not sure how I can get into teaching now. I think leaving Northern Ireland could help but I can’t do that until I’ve secured a job so I can pay my way. The fact I don’t have my own space makes me more keen to move as my parents and I are a bit on top of each other. I try to get out, going to gym classes to get some space and meet other young people. That helps me feel good.’

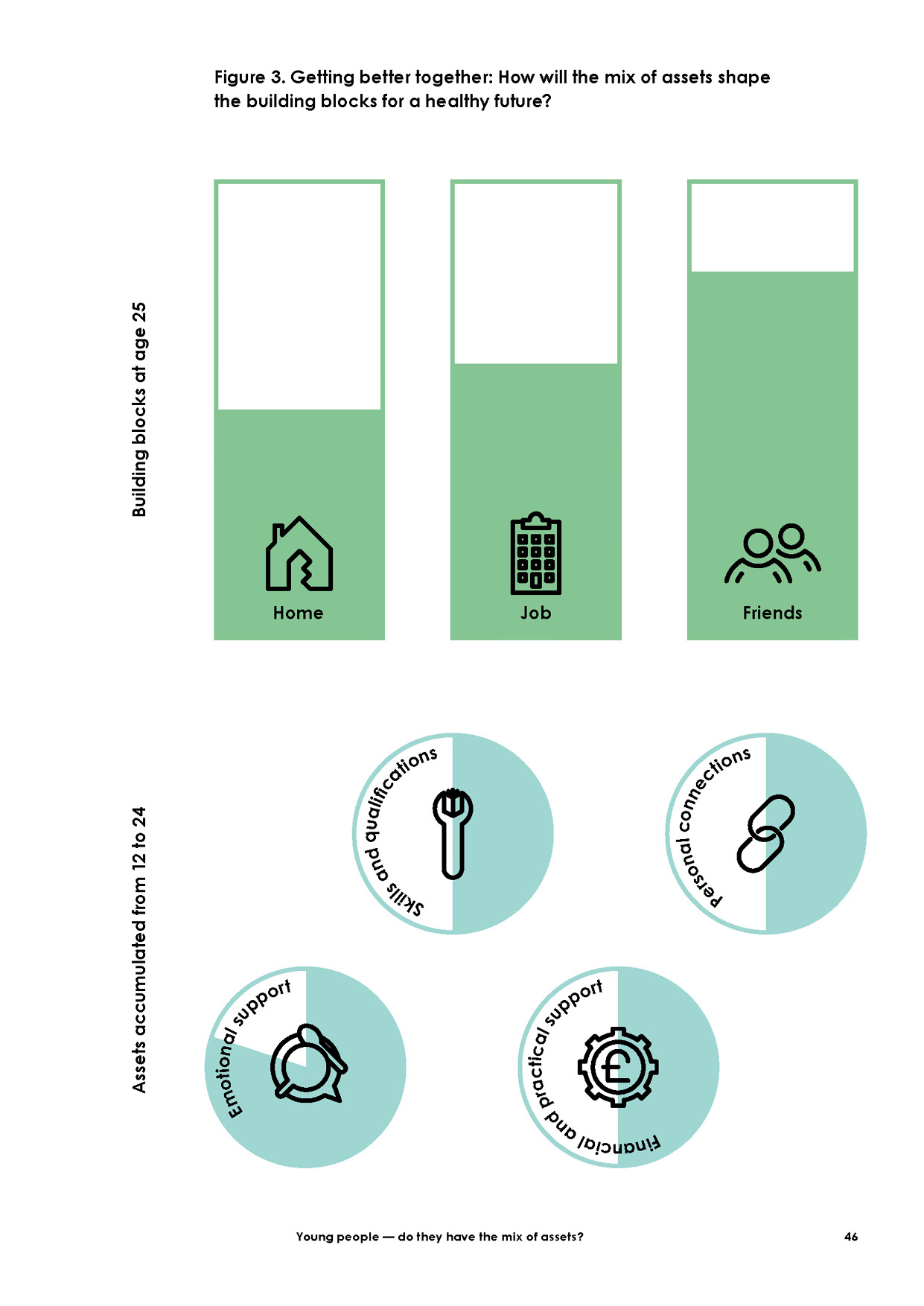

Getting better together

Young people in this group had experienced struggles in the past and were working to move on from these previous challenges. For example, some dropped out of school with few qualifications. Others fell in with the wrong crowd or had difficult home lives, which led to periods of homelessness for some. Often, though not always, these challenges came about due to socioeconomic circumstances out of the person’s control. However, once they hit their 20s they commonly went through a turning point often due to social support or intervention from others, such as a formal or informal mentor. They then went on to make life changes – for example, by returning to education, starting their own businesses or pushing themselves to progress at work.

Many in this group had strong social connections who could offer advice and guidance. They also had high levels of emotional resilience due to the experiences they had overcome. They wanted to make up for previous setbacks and tended to be in control and confident that they would achieve their goals. However, their optimism did not extend to trust in institutions and government. They were likely to have had negative experiences with the education, housing and benefits systems.

There was variation within this group. Some young people had fewer social connections but higher levels of emotional and financial support from a partner or family. This meant that even though they had low levels of skills and qualifications, they had a support structure around them which meant they had opportunities, such as going back to college, as a result of being able to live at home rent-free. Their family or partner might lack connections, but they were able to offer emotional support and encourage them to achieve their ambitions.

Conversely, other young people in this group lacked practical and financial support but had more access to relevant and meaningful connections. However, despite lacking financial support, they had still overcome the challenge thanks to having someone in their life to offer advice and guidance. In some instances, this could be more valuable than financial help. Where family relationships were poor, young people tended to rely on friends, social housing or private renting. This lack of control over where they lived meant they prioritised saving for more secure housing.

Figure 3. Getting better together: How will the mix of assets shape the building blocks for a healthy future?

‘I like my work and I’m happy with my salary but would like more per hour so I’ve decided to go to uni. I’ve moved back home, which I enjoy as I can save money and my mum does my washing.’

Leeds

Orla, 25, Bristol

‘I grew up in a council estate just outside of Bristol. I didn’t really get on with my parents or my older brother, and no one in my family ever seemed to hold down a permanent job. I hated it so much that when I was 16 I left to live at my boyfriend’s place. I knew I wanted a better life and to earn enough to set myself up but I struggled to keep up in school, and was diagnosed late with dyslexia. Luckily, my maths teacher, Mr Reynolds, saw that I just needed a little extra help. I’d always liked design technology so Mr Reynolds suggested I apply for an electrician apprenticeship. He helped me write the application and connected me with someone who gave me some extra maths coaching.

‘The apprenticeship was a great opportunity to earn some money and it meant my boyfriend and I managed to move out of his parents’ house and get our own space. I worked hard on the apprenticeship and was offered a full-time job, which I love. We’ve now managed to get a small flat above a shop. It was in rubbish condition when we moved in, but we’ve spent our spare time doing it up so it finally feels like home. We’re saving with the hope of being able to part-own in the future. It’s still not easy as my boyfriend is struggling to find permanent work, but we’re optimistic and know if we continue to work hard, it will eventually pay off.’

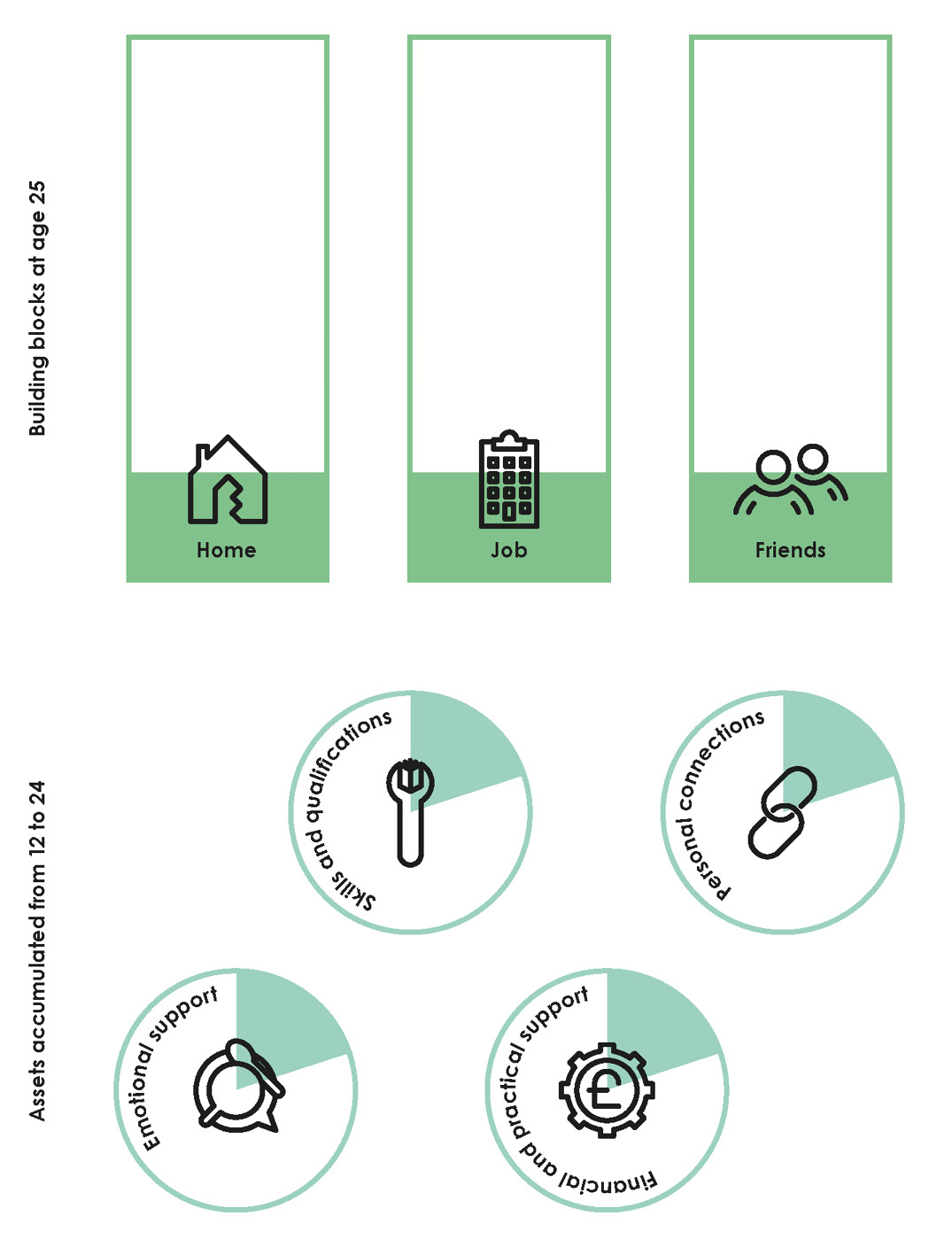

Struggling without a safety net

Young people in this group had the least access to skills and connections and to emotional, practical and financial support. Unlike those in the ‘getting better together’ group, these young people were unable to access appropriate support. They were also likely to live in areas with poor job markets, but their lack of financial stability prevented them from being able to move elsewhere.

They tended to come from less affluent areas and some had had to rely on the state for support. They had low levels of resilience and high levels of anxiety due to the constant threat of debt and homelessness.

Young people in this group were at risk of experiencing homelessness, although some were in social housing. Others were in insecure privately rented housing where the conditions are poor. Often they were unemployed, or in insecure work with temporary contracts, long hours and inflexible shifts. They often had poor relationships with employers as they feel unsupported and that there is no interest in their personal development.

While a small number of young people who are ‘struggling without a safety net’ may be facing serious challenges, many were managing to keep their head above the water due to having slightly more emotional support, or slightly more practical or financial support. This was often from a partner. However, overall they have the lowest sense of personal agency and control over their future and often felt isolated and alone.

Figure 4. Struggling without a safety net: How will the mix of assets shape the building blocks for a healthy future?

‘I’ve been in situations where people have their parents give them money, whereas I seem to be in the situation that however hard I work, I wasn’t getting the same things they were.’

Cardiff, C2DE, living independently

Jack, 24, Newcastle

‘I was born in Hull and lived there with my mum in a local council flat. My dad died when I was little so it was always just me and my mum – she never had a job, and I didn’t have any contact with my extended family. I didn’t like school much and often didn’t even bother to turn up. I ended up getting expelled after a fight with another lad, so left with no qualifications. That’s when I fell in with a bad crowd and we hung out drinking and then moved into taking drugs, and eventually ended up getting arrested for shoplifting. We were all in the same boat, with no qualifications, making ends meet with casual labouring.

‘When mum died, leaving me on my own aged 22, I didn’t know how to cope and got angry and fought with my friends. I had to get away, so went to Newcastle where I had an old friend working in construction. He sorted me out with some casual construction jobs and let me sleep on his sofa, which was alright until he asked me to leave. I didn’t know anyone else in Newcastle and couldn’t access housing, so I ended up on the streets.

‘Thankfully, things are really starting to look up. I’ve been put in touch with a homeless charity who can help me find somewhere safer to stay. I also reached out to a guy I met through my previous construction job, and he reckons he could have some work soon that I can pick up. I can’t wait to be earning a bit of money.’

Discussion

The UK has seen huge economic and social progress in the last 30 years. The drive to increase the number of young people going to university has resulted in a society in which almost half (49%) of young people in England today go on to higher education. Many of the health-promoting behaviours of this generation have also improved. Rates of teenage pregnancy have fallen, as has the use of alcohol and drugs. In terms of their personal life, sex and sexuality, increasing tolerance in society means some young people have the freedom and ability to determine their own future at a level that previous generations could not have hoped for.

But, despite these positive changes, looking through a broader lens, young people themselves report a less optimistic story. When it comes to the social determinants of health, young people are losing ground.

A complex world, and complex individuals within it

During the engagement work, young people described lives of considerable insecurity in which reliance on work as a place of belonging, financial stability and reliability was hard to achieve. For many, housing, too, was precarious, and made it impossible to plan a future. They described themselves as having aspirations that extended beyond the opportunities around them. They described a complex world in which it was difficult for many of them to establish the building blocks fora healthy future. These findings are supported by data and research from other organisations.

The young people also described high levels of anxiety. They spoke of a crisis of self-esteem in which they felt they had ‘failed’. The national-level data also support this, showing concerning degrees of loneliness and mental health concerns.

For some young people, the challenges they experience are just a part of the process of maturity. With good social networks and with a financial safety net provided by their parents/carers, they may well be able to withstand the impact of insecurity and uncertainty. But a large proportion of young people lack the financial and personal support of family. Many young people are also finding that the skills and qualifications they have gained cannot be translated into the building blocks for a healthy life. The damage to their long-term prospects of this is potentially very great.

The impact on future health

This matters, first and foremost, because of what it means for the young people involved. But it also matters because experiences between the ages of 12 and 24 will play a crucial role in determining young people’s health and wellbeing in the long term. The gains made as a society in improving the health of previous generations may well be eroded by the precariousness and instability of the lives some young people are facing.

The inquiry has identified the importance of ensuring that young people are able to build the assets they need to secure, as they transition into adulthood, the building blocks for a healthy future. Furthermore, the impact of many of the wider structural challenges young people face in the housing and labour market, affect the extent to which they are able to realise value from the assets they have accumulated.

The long-term health of the population is one of the greatest assets our country holds. The decline of this asset should concern us all. When today’s young people enter middle age without the fundamentals needed for a healthy life, society may regret not having taken action sooner.

What next?

The situation facing young people is complex, and there is no single solution. As with many complex problems, the way forward will rely on many individuals and organisations working together in a number of different ways. Government, business, education institutions, the voluntary sector, communities and individuals will all have a role in piecing together this puzzle.

These early findings point to a need for the UK to take an approach that supports every young person’s opportunities for a healthy future. Both in terms of how young people in differing circumstances are supported to build the assets need to secure the building blocks for a healthy future. And also how they are able to realise value from these assets regardless of where in the UK they live. This will require policy understanding and action in the UK and devolved governments, and among other national players.

At a local level, the litmus test of a flourishing society should be whether it is good for the young people who live within it. There are interventions that can be fundamental in changing the fortunes of young people, and these need to be understood, evidenced and scaled. Communities need to understand their responsibilities to the young people who live in them and promote local action to address variation in young people’s opportunities for a healthy life.

To address this need, in 2018 and early 2019 the Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry will be undertaking a programme of research policy, communications and stakeholder work to begin a conversation about what needs to change. Find out more: www.health.org.uk/futurehealthinquiry

In the second half of 2018, the Health Foundation will also be undertaking a programme of site visits, profiling five places across the UK, and engaging with young people, professionals and system leaders to understand what makes a good place for young people. Findings will be reported through the course of the inquiry.

More about the Young people’s future health inquiry

The Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry is a two-year programme, exploring the future health of young people today across the UK.

As well as the engagement work with young people, the inquiry also involves site visits in various locations across the UK, along with a research programme run by our partners at the Association for Young People’s Health and the UCL Institute of Child Health. The inquiry will culminate in a policy analysis and development of recommendations, expected in 2019.

Acknowledgements

The Health Foundation would like to thank the young people who participated in the engagement work.

We would also like to thank all those who have contributed to the report.

Appendix: research methodology

The Health Foundation commissioned Kantar Public, an independent social research agency, which partnered with Livity, a youth engagement specialist, to conduct an engagement exercise with young people living in the UK aged 22 – 26.

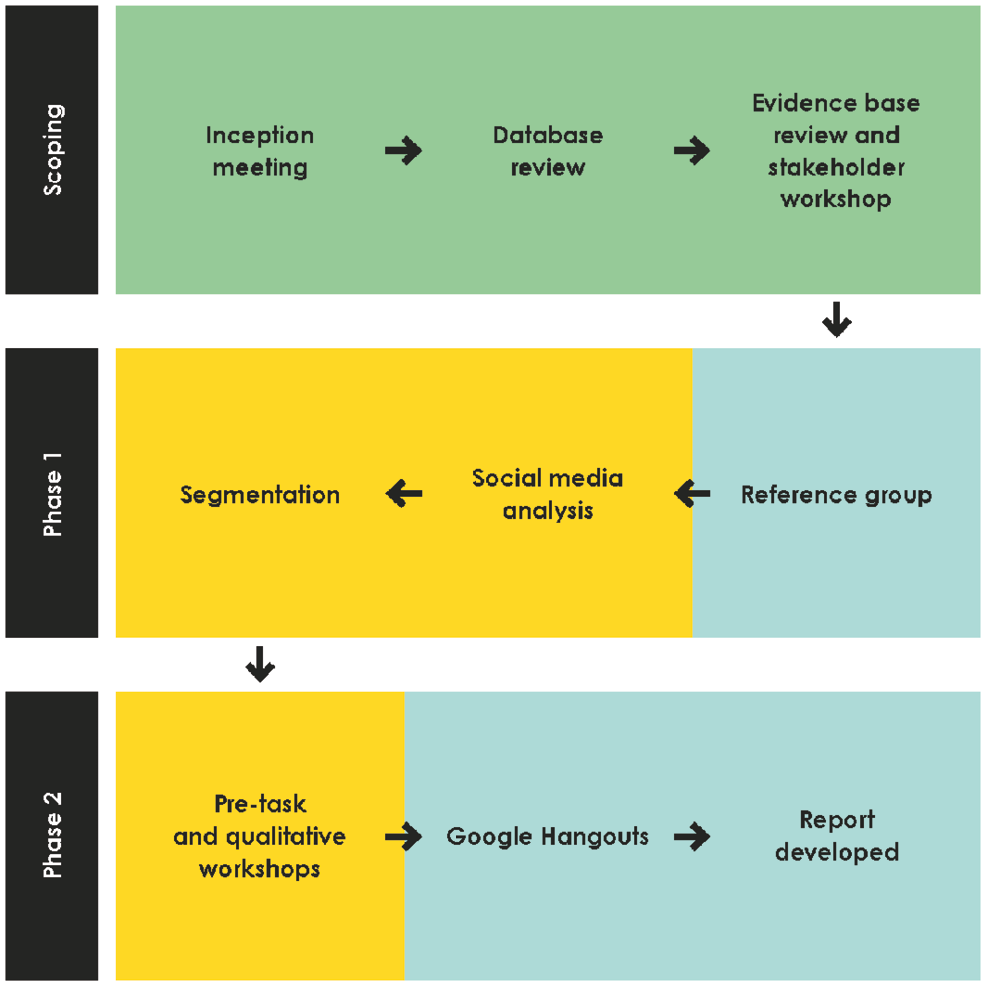

The engagement exercise adopted a mixed method and iterative research approach, which consisted of three distinct phases incorporating both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

- The project began with a database review to gather existing insight on this cohort of young people and a stakeholder workshop.

- Phase 1 involved mobile discussions with a 10-person reference panel, social media analysis and a segmentation based on the 2017 Next Steps dataset of about 7,700 young people aged 25.

- Phase 2 comprised a mobile app diary followed by half-day qualitative workshops in London, Leeds, Glasgow, Cardiff and Newtownabbey (including 80 young people in total).

- Phase 3 included hosting four ‘Google Hangouts’ with young people.

- The report was then developed, including work by Livity in conjunction with young people to describe some of the findings in their own words.

The analysis to develop the assets and groups drew on the multiple data sources collected during the engagement work, including moderator notes from the workshops (such as audio recordings and materials completed by participants in the workshops) and data generated through the mobile app (including rating scales, open-ended text, discussion threads and photos). Matrix mapping was used to analyse the large volumes of data. Structured charts were used to map data against the research objectives and emergent key themes. The data were systemically analysed to look for themes and explore variation across subgroups. Formal analysis brainstorming sessions were held following each phase of research, where researchers explored findings against each of the key themes in detail, as well as against the overarching objectives.

These findings were then tested with a group of young people, with descriptions of the assets, titles of the groups and descriptions co-developed with Livity.

The Health Foundation also commissioned Opinion Matters, an insights and market research agency, to conduct an online survey of those aged 22–26 and gather their views on the challenges facing young people. A total of 2,000 participants from across the UK were surveyed between 4 April and 9 April 2018.

We asked them the following questions.

How important do you think it is to have the following when growing up?

- Opportunity to achieve the right skills and qualifications for your chosen career.

- The right relationships and networking opportunities to help enter/progress in the working environment.

- Financial and practical support from my family (eg helping with living costs/being able to live at home and avoid paying rent).

- Emotional support.

To what extent did you have the following when growing up?

- Opportunity to achieve the right skills and qualifications.

- The right relationships and networking opportunities to help enter/progress in the working environment.

- Financial and practical support from my family (eg helping with living costs/being able to live at home and avoid paying rent).

- Emotional support.

How easy was it and/or do you think it will be for you to obtain the following?

- I found/would find high quality, affordable housing in my local area.

- I found/would find secure work which is fairly paid and has scope for career growth and development.

- I found/would find happy and fulfilling relationships with family, friends and partners.

- Young people generally can find high quality, affordable housing in my local area.

- Young people generally can find secure work which is fairly paid and has scope for career growth and development.

- Young people generally can find happy and fulfilling relationships with family, friends and partners.

How much do you agree/disagree with the following?

- Most people I know of my age couldn’t afford to move out of home.

- Either myself or friends of mine have done unpaid internships in order to get a job.

- Young people today are under pressure to appear or behave in a certain way on social media.

- It’s all about who you know when it comes to finding a job – those with personal networks and connections have an advantage.

- Most jobs I’ve seen that are of interest to me are temporary or contract positions.

References

- Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives: The Marmot review 2010. Available from http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

- ONS. 2011 census: Usual resident population by single year of age, unrounded estimates, local authorities in the United Kingdom. 2013. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/2011censuspopulationestimatesbysingleyearofageandsexforlocalauthoritiesintheunitedkingdom

- Sawyer S et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012. 379: 1630 - 40

- World Health Organisation. World development report 2007, development and the next generation. 2007. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/5989

- Patton G et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet.387(10036): 2423–2478

- Independent Advisor on Poverty and Inequality. The life chances of young people in Scotland: A report to the First Minister. (2017). Available from: www.gov.scot/Resource/0052/00522051.pdf

- Chartered Institute of Environmental Health. Physical health – key issues. 2015. Available from: http://www.cieh-housing-and-health-resource.co.uk/housing-conditions-and-health/key-issues/

- Shelter. The impact of bad housing. 2018. Available from: http://england.shelter.org.uk/campaigns_/why_we_campaign/housing_facts_and_figures/subsection?section=the_impact_of_bad_housing

- Shelter. 1 in 5 adults suffer mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and panic attacks due to housing pressures. 2017. Available from: https://england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_releases/articles/1_in_5_adults_suffer_mental_health_problems_such_as_anxiety,_depression_and_panic_attacks_due_to_housing_pressures

- Office for National Statistics; www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/young-adults-live-parents-at-home-property-buy-homeowners-housing-market-a8043891.html

- Office for National Statistics. Young people’s well-being: 2017. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/youngpeopleswellbeingandpersonalfinance/2017

- Tosi, M, Grundy E. Returns home by children and changes in parents’ well-being in Europe. Social Science & Medicine. 200: 99–106. 2018.

- Resolution Foundation. Stagnation generation: The case for renewing the intergenerational contract. 2016. Available from: http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/stagnation-generation-the-case-for-renewing-the-intergenerational-contract/

- Corlett A, Judge L. Home affront: Housing across the generations. Intergenerational Commission. 2017. Available from: www.intergencommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Home-Affront.pdf

- Chartered Institute of Environmental Health. Mental health and wellbeing – key issues. Available from: www.cieh-housing-and-health-resource.co.uk/mental-health-and-housing/key-issues/

- Shelter. The need for stable renting in England. 2016. Available from: http://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1236484/The_need_for_stability2.pdf

- Generation Rent. 2014. Available from: http://www.generationrent.org/generation_rent_decide_2015_election

- Centrepoint. Youth homelessness in the UK. Available from: https://centrepoint.org.uk/youth-homelessness/

- Centrepoint. Hidden homelessness revealed- new poll shows shocking numbers of sofa surfers. 2014. Available from: http://intranet.centrepoint.org.uk/news-events/news/2014/december/hidden-homelessness-revealed-new-poll-shows-shocking-numbers-of-sofa-surfers

- Corlett A, Judge L. Home affront: Housing across the generations. Intergenerational Commission. 2017. Available from: www.intergencommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Home-Affront.pdf

- Centrepoint. Hidden homelessness revealed- new poll shows shocking numbers of sofa surfers. 2014. Available from: http://intranet.centrepoint.org.uk/news-events/news/2014/december/hidden-homelessness-revealed-new-poll-shows-shocking-numbers-of-sofa-surfers

- The Albert Kennedy Trust. LGBT youth homelessness: A UK national scoping of cause, prevalence, response & outcome. 2015. Available from: www.akt.org.uk/research

- Tarani Chandola, Nan Zhang. Re-employment, job quality, health and allostatic load biomarkers: prospective evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(1): 47–57.

- Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review 2010. Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. 2010. Available from: www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review-strategic-review-of-health-inequalities-in-england-post-2010

- Centre for Longitudinal Studies. Being on a zero-hours contract is bad for your health, new study reveals. 2017. Available from: www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/news.aspx?itemid=4623&itemTitle=Being+on+a+zero-hours+contract+is+bad+for+your+health%2c+new+study+reveals+&sitesectionid=27&sitesectiontitle=News&returnlink=news.aspx%3fsitesectionid%3d27%26sitesectiontitle%3dNews%26page%3d2

- Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review 2010. Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. 2010. Available from: www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review-strategic-review-of-health-inequalities-in-england-post-2010

- Gregg P, Tominey E. The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Economics, 2(4):487–509. 2005.

- Gardiner L. Stagnation generation? The case for renewing the intergenerational contract. 2016. Available from: www.intergencommission.org/publications/stagnation-generation-the-case-for-renewing-the-intergenerational-contract/

- ONS. Contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of hours. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/contractsthatdonotguaranteeaminimumnumberofhours/september2017

- Centre for Longitudinal Studies. Being on a zero-hours contract is bad for your health, new study reveals. 2017. Available from: www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/news.aspx?itemid=4623&itemTitle=Being+on+a+zero-hours+contract+is+bad+for+your+health%2c+new+study+reveals+&sitesectionid=27&sitesectiontitle=News&returnlink=news.aspx%3fsitesectionid%3d27%26sitesectiontitle%3dNews%26page%3d2

- Department for Education. Participation rates in higher education 2006-2016. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/participation-rates-in-higher-education-2006-to-2016

- Sutton Trust. Sutton Trust Young People Omnibus Survey 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.suttontrust.com/research-paper/aspirations-polling-2017-university-fees-debt-attitudes/

- ONS. Graduates in the UK labour market: 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/graduatesintheuklabourmarket/2017

- The Princes Trust. Macquarie youth index 2018 annual report. 2018. Available at: https://www.princes-trust.org.uk/about-the-trust/news-views/macquarie-youth-index-2018-annual-report

- RWJF. Exploring the social determinants of health. 2011. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2011/rwjf70447

- CIPD. Assessing the early impact of the apprenticeship levy – employers’ perspective. 2018. Available from: https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/assessing-the-early-impact-of-the-apprenticeship-levy_2017-employers-perspective_tcm18-36580.pdf

- Social Mobility Commission. The class pay gap and intergenerational worklessness. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-class-pay-gap-within-britains-professions

- ONS (2017). Young people not in education, employment or training (NEET). 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/bulletins/youngpeoplenotineducationemploymentortrainingneet/november2017#economically-inactive-young-people-who-were-neet

- ONS. EMP17: People in employment on zero hours contracts. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/emp17peopleinemploymentonzerohourscontracts

- ONS. Graduates in the UK labour market: 2017. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentand employeetypes/datasets/graduatesintheuklabourmarket2017

- HM Treasury. National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates. Available from: www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage-rates

- Association for Psychological Science. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. 2015. Available from: www.ahsw.org.uk/userfiles/Research/Perspectives%20on%20Psychological%20Science-2015-Holt-Lunstad-227-37.pdf

- Marjoribanks D, Darnell Bradley A. The way we are now – the state of the UK’s relationships 2016. You’re not alone: The quality of the UK’s social relationships. Relate. 2017. Available from: www.relate.org.uk/policy-campaigns/publications/youre-not-alone-quality-uks-social-relationships

- ONS. Young people’s well-being: 2017. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/youngpeoples wellbeingandpersonalfinance/2017

- Royal Society of Public Health. Status of mind: social media and young people’s mental health. 2017. Available from: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/campaigns/status-of-mind.html

- Time to Change. 2017. Changing the way we all think and act about mental health. Available from: https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/sites/default/files/In-Your-Corner-Campaign-Narrative.pdf

- ONS. Causes of death over 100 years. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/causesofdeathover100years/2017-09-18

- Children’s Society. Understanding Adolescent Neglect: Troubled teens. 2016. Available at: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/troubled-teens-executive-summary.pdf

- Public Health England, UCL IHE. Reducing social isolation across the lifecourse. 2015. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-action-on-health-inequalities-reducing-social-isolation

- ONS. Young people’s well-being: 2017. 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/youngpeoples wellbeingandpersonalfinance/2017

- BCC. BCC quarterly economic survey: Skills shortage biggest risk for business. 2018. Available from: www.britishchambers.org.uk/press-office/press-releases/bcc-quarterly-economic-survey-skills-shortage-biggest-risk-for-business.html

- The Princes Trust. Macquarie Youth Index. 2018. Available from: www.princes-trust.org.uk/about-the-trust/news-views/macquarie-youth-index-2018-annual-report

- Department for Education. Youth cohort study and longitudinal study of young people. 2010. Available from: http://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-cohort-study-and-longitudinal-study-of-young-people-in-england-the-activities-and-experiences-of-19-year-olds-2010