Key points

In this briefing, we analyse the challenges for health and social care following the publication of The NHS long term plan and look at the implications of the plan for activity levels and the workforce in the NHS in England. We set out funding scenarios for areas of health spending outside NHS England’s budget and examine the potential impact on wider public spending.

The funding context

- In June 2018, the government set out the funding increase that NHS England would receive between 2018/19 and 2023/24. Allowing for the latest inflation estimates, NHS England’s budget is due to increase in real terms by £20.6bn,* an average of 3.3% per year. This rate of increase is below the historic average of 3.7% per year, but above the average growth rate of the last decade (2.1% per year). It is broadly in line with projections by the Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) that maintaining current standards of care with a growing and ageing population and a rising burden of chronic disease will require total health spending to increase by 3.3% per year.

- Adult social care has fared worse over this decade, with spending having fallen by 5% in real terms since 2010/11. Even with recent increases, spending was around £1bn less than in 2010/11, at £17.8bn. The government has yet to set out long-term funding plans for social care.

- The budget for the wider Department of Health and Social Care (including public health, capital and workforce education and training) has not yet been decided beyond 2019/20. Public spending for the next 3 years was due to be set out in the planned 2019 Spending Review. However, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury has stated that it is unlikely to go ahead as planned, following confirmation of the Prime Minister's resignation and because of the lack of an EU-withdrawal agreement. This means that these long-term decisions are likely to be delayed again.

NHS spending and The NHS long term plan

- The NHS long term plan proposes to achieve better outcomes by focusing the additional funding on the key areas of mental health, and primary and community services.

- Spending on mental health services will rise by £2.3bn over the next 5 years (4.6% per year), while spending on primary and community health services will rise by £4.5bn (3.8% per year). Funding for these areas will therefore grow at a faster rate than the overall NHS budget.

- However, this results in a challenge to other areas of NHS activity, which will see lower growth in spending despite having to tackle the needs of a growing and ageing population with increasingly complex health needs.

Activity growth and moderation

- Acute hospitals have seen the amount of care they provide rise by 3.0% per year on average between 2010/11 and 2016/17, with growth of 3.6% in 2016/17 alone (the most recent year for which comprehensive data are available). This covers all care provided in acute settings, including inpatient and outpatient care.

- Over the next 5 years, without any improvements in the quality or range of services, Health Foundation projections suggest that acute and specialist hospital activity will need to rise by at least 2.7% per year just to keep pace with demand.

- The additional funding available for acute and specialist care under The NHS long term plan would be sufficient for activity growth of up to 2.3% per year. This implies a requirement for the NHS to significantly moderate growth in demand for hospital services over the next 5 years or make difficult trade-offs in how the investment is allocated.

- The amount of activity that can be undertaken within a given budget is critically dependent on pay. The latest pay deal for Agenda for Change staff means that pay for most NHS staff will rise in real terms until 2020/21. Beyond that point we've assumed that to recruit and retain staff, pay will not fall behind the earnings growth across the economy as a whole. Lower pay growth would allow higher activity growth, however it would create a new challenge: after years of below-inflation pay increases, with a high employment rate and ongoing challenges in recruiting staff from overseas, it is hard to see how the NHS could further constrain pay and recruit and retain enough staff.

- If the rate of growth in demand for hospital care can’t be reduced, there is a real risk that the planned additional investment in mental health, and primary and community care will not materialise and, once again, funding will be diverted to acute and specialist hospitals.

- How hospitals might moderate demand is also important. Recent years have seen rapid growth in emergency activity and slower growth in planned care. From 2008/09 to 2017/18, A&E activity saw average annual growth of 4.7%, compared with 2.2% for elective inpatient admissions. The result is that waiting times have increased and the NHS hasn’t met the 18-week standard for planned operations since February 2016 or the 62-day cancer waiting time standard since December 2015. If the NHS is not able to genuinely moderate demand, this could result in continued inability to meet waiting-times standards, as funding fails to match demand for care.

- This juggling act is made harder by the phasing of the new NHS England funding, which is not spread evenly, let alone frontloaded, over the next 5 years (the biggest increase in funding coming in 2023/24). The backloading of funding runs counter to the needs of the service; The NHS long term plan’s vision for the NHS is predicated on improvements to mental health, and primary and community care services reducing potentially avoidable hospital admissions. But such substitution cannot be instantaneous: investment in these services will take time to have an impact, so a period of ‘double running’ is hard to avoid. Without upfront investment or provision for double running, it will be extremely challenging for the NHS to moderate demand to the extent that would be required to avoid diversion of funding back into acute services or increased waiting times.

The workforce challenge

- Another major challenge facing the NHS in delivering the goals of The NHS long term plan is the service’s workforce. NHS trusts currently have an estimated staffing shortfall of more than 100,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff – around 1 in 10 posts. According to analysis by the Health Foundation, The King's Fund and the Nuffield Trust, this could grow to 160,000 by 2023/24. This includes shortages of 70,000 FTE nurses working in hospital and community services, and 7,000 GPs.

- The ambition laid out in The NHS long term plan to increase the share of resources going to mental health, and primary and community services means that the NHS needs to grow these areas of nursing at a faster rate. The number of mental health nurses will need to increase by 10,300 (4.6% per year) and the number of community nurses by 7,000 (3.9% per year) by 2023/24. Over the last 5 years, the number of nurses working in mental health and community settings has actually fallen by 1,700 and 500 FTE respectively.

- The training pipeline for both mental health and community nursing is also a concern due to recent reductions in the number of mature applicants to nursing degrees, who are more likely to study mental health and learning disability nursing.

Other areas of health spending

- Although the government has committed additional funds to NHS front-line services, it is clear that delivering the ambitions to improve services set out in The NHS long term plan will be a major challenge.

- Whether the NHS will be able to start to transform care and outcomes over the next 5 years will depend to a large degree on the forthcoming spending for public health, health care capital investment, NHS education, training and staff development – areas of spending that directly affect patient care but fall outside of NHS England’s budget.

- These budgets should be set alongside that of NHS England due to their interdependency. Initially, the Spending Review 2019 was planned to set day-to-day budgets for 3 years, and capital budgets for 4 years. However, there is considerable political and economic uncertainty due to Brexit, meaning it could cover a shorter timeframe. Decisions about these budgets beyond 2020/21 have been delayed again, seriously compromising the NHS's ability to deliver the goals of The NHS long term plan.

- Capital, public health and workforce education and training have all been reduced in recent years. For example, the public health grant has been cut by 15%, and Health Education England’s budget by 24%, from their previous peaks in 2015/16 and 2013/14, respectively.

- Health Education England’s budget covers the costs of education and training clinical staff (including a contribution to the salary costs of doctors in training and clinical placements) and development (including continuing professional development (CPD) courses undertaken by NHS staff).

- Without investing more in both current staff and the training pipeline of new staff, the NHS’s staffing shortages will worsen. As outlined in our recent analysis with The King's Fund and the Nuffield Trust, investing £900m in Health Education England’s budget would allow national investment in workforce development to return to previous levels, and would allow nurses to be given additional financial support to improve their retention and engagement.

- In 2013/14, public health services were transferred from primary care trusts to local government. Funding for this forms part of the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget and is allocated to local government through the public health grant.

- The public health grant allows local authorities to provide services that maintain and improve people’s health, but this has been reduced in real terms by £850m since 2014/15. That equates to a reduction in the grant of 23% in real spending per person between 2014/15 and 2019/20.

- Reversing these cuts would take the public health grant in 2020/21 to a total of £4.2bn, just over a £1bn higher than that year’s provisional allocation of £3.1bn. Growing the public health grant in line with increases to NHS England’s budget (so that the share of its spending dedicated to public health is maintained) would require a £1.5bn a year real-terms increase by 2023/24, taking the grant up to £4.6bn a year, with the additional funding phased in over the next 4 years.

- Day-to-day running costs make up the bulk of NHS funding, but capital investment in buildings, equipment and IT is vitally important to delivering high-quality patient care.

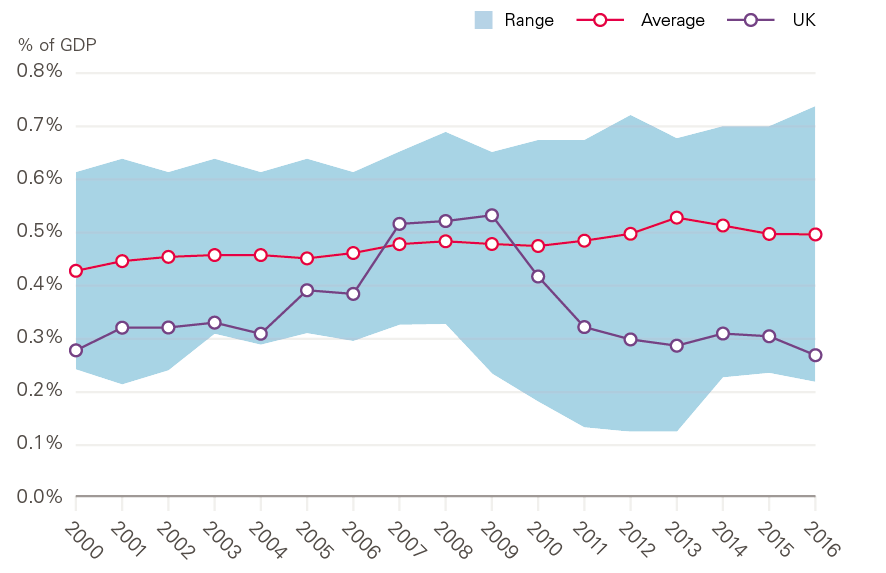

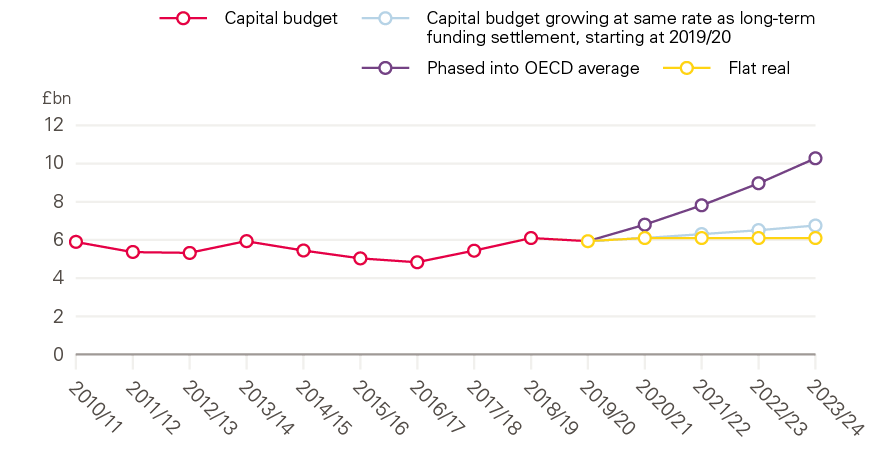

- Capital investment has been cut in recent years to meet rising pressures on day-to-day running costs, with 6 years of transfers from the capital budget to the revenue budget. Capital per worker in trusts reduced by 17% between 2010/11 and 2017/18. The result is a rising backlog of maintenance and a lack of investment to support innovation. Across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), on average, countries spend 0.51% of their GDP on health care capital. In the UK this is just 0.27%. Matching the OECD average would mean increasing the Department of Health and Social Care's capital budget from £5.9bn in 2019/20 to £10.3bn in 2023/24.

Completing the funding picture

- If health spending beyond NHS England’s budget grows in line with inflation, then the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget will increase from £139bn to £155bn in 2023/24. This would be a growth rate in the overall budget of just 2.9% per year – below the level required to maintain current standards of care. Under this scenario, funding would fail to keep up with growing demand, and the quality of care provided is likely to deteriorate.

- If the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget were to grow at 3.4% (the real- terms growth rate originally planned for NHS England) then health spending would rise to £159bn. This is roughly in line with estimates from Securing the future for the funding levels required to maintain current standards of care, given a growing and ageing population and a rising burden of chronic disease.

- If the balance between day-to-day spending and investment in prevention, buildings and equipment, and staff is to be restored, health spending would grow to £163bn – a growth rate of 4.1% per year over the next 5 years. This is roughly in line with estimates from Securing the future for the funding levels required to invest in and modernise the health service. However, when combined with the past 5 years of slow growth, this equates to just 3.0% per year over the decade to 2023/24.

Social care

- The NHS long term plan makes it clear that the NHS cannot be considered in isolation; an ageing population with complex long-term health conditions needs effective health and social care services. Equally, working age adults are a growing number and percentage of the people needing social care.

- The NHS long term plan was developed with the clear expectation of a sustainable funding settlement for social care, stating that ‘the government … committed to ensure that adult social care funding is such that it does not impose any additional pressure on the NHS over the coming 5 years. That is the basis on which the demand, activity and funding in The NHS long term plan have been assessed’. Without this funding, the scale of the challenge for the NHS will rise, and the problems in social care will worsen.

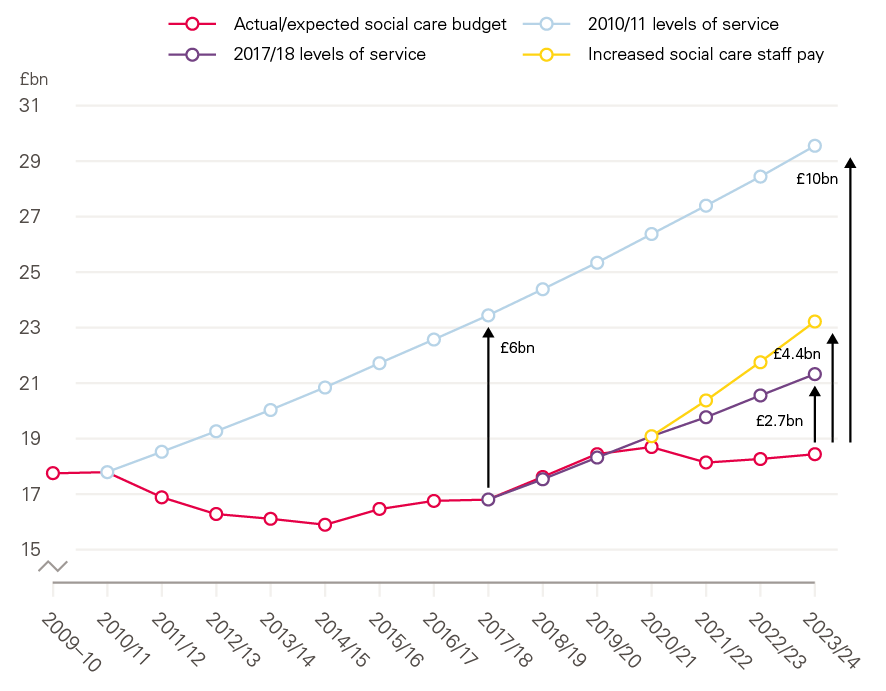

- There are different ways to calculate the funding required to meet The NHS long term plan test. As a minimum, social care funding would need to increase by £4.2bn by 2023/24 (3.6% per year) to prevent falls in access to care or quality. This is £2.7bn more than the projected budget for 2023/24. If social care pay were to grow at the same rate as the NHS pay deal for Agenda for Change staff, in order to improve recruitment and retention, this additional cost pressure would bring the funding gap to £4.4bn in 2023/24.

- Reinstating access to care and quality to 2010 levels would require adult social care funding in 2023/24 to reach £29.6bn (£11.9bn more than in 2017/18 – an increase of 67%).

- This is complicated further by reforms to local government financing, with more reliance on council tax and business rates. It is not clear that local councils can support the growing need for adult social care by being dependent on these funding streams, especially without crowding out other services such as public health and housing.

The wider public spending context and health

- NHS front-line services have been protected relative to other areas of public spending over recent years, which has allowed the NHS to broadly maintain standards of care. But the result of years of short-term funding decisions is that the shift of investment has moved away from areas of investment in the future – the workforce, public health, and capital. Funding is now out of kilter and will need to be rebalanced to ensure that the ambitions set out in The NHS long term plan are realised, and that the NHS can continue to deliver year-on-year gains in productivity and value for money. The phasing for additional spending is also a problem, with NHS England’s settlement being backloaded, rather than allowing greater investment in earlier years. This means the money is at risk of being spent poorly.

- If the much-needed additional funding for mental health, and primary and community care services is to materialise then a realistic plan for moderating acute and specialist activity is needed now. The risk otherwise is that acute activity is moderated in a haphazard way, which risks leading to unmet need, particularly for the most disadvantaged, or that acute activity growth eats into the money for mental health, and primary and community care. After 10 years of low funding growth, the additional funding is vitally important, but it is not a panacea.

- To deliver real benefits to patients, the investment in NHS England over the next 5 years needs to be matched with funding to ensure that the NHS has the workforce and facilities it needs, and that social care and public health are able to play their part to support people to live healthy, high-quality lives. This benefits the population as a whole: people being healthy increases their productivity while they are in work, supports them to be in work, reduces the need for informal carers to take time off, and much more.

- Finding additional funding will be tough. Health spending has grown as a share of GDP and it will continue to do so. Over recent years the government has increased health spending by cutting other areas of public spending – health spending has increased from 16.7% of public service spending in 2009/10 to 19.3% in 2018/19, reflecting the overall constraints on public spending.

- The current Treasury plans for public spending over the next 5 years would see government-wide spending grow by 7% – less than half the growth rate of NHS England. This would mean extra health spending would put further pressure on other public services. The health of a population is affected by much more than just health spending – it is also determined by the economic and social conditions in which people live and work (the Marmot Review showed in 2010 how important these wider social determinants are to health). It is important that increased NHS spending is not at the expense of the public services and welfare spending that supports health.

- Securing the future concluded that we face one of the biggest choices in a generation. If we are to have a health and social care system that meets our needs and aspirations, we will have to pay a lot more for it over the next 15 years. The UK is currently a relatively low taxed country – significantly below the EU-15 and G7 average. We can’t, and shouldn’t, rely on cutting spending elsewhere to fund the NHS and care system. At some point we will have to pay more in tax. But it is a choice: higher taxes and a health and social care system that meets our expectations and improves over time, or taxes at current levels and more constrained health and care services delivering less than we have become accustomed to.

* In this briefing, numbers are given in 2019/20 prices using March 2019 deflators for consistency. As a result, some numbers may not match those in official announcements made in 2018/19. We assume that NHS England’s cash-terms budgets are confirmed as alongside The NHS long term plan.

Foreword

Just over a year ago, NHS Confederation commissioned the Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies to undertake a study into the funding needs of the UK’s health and care system for the next 15 years. The resulting report, Securing the future, exposed the relentless pressure that is hitting the health and care system, and the funding uplifts critically needed to sustain current provision and modernise the service.

The report was timely and helped influence the climate leading up to the government’s announcement of an improved financial settlement for the NHS. Based on this, NHS England published a long-term plan which spells out a vision for improving patient care over the next decade and how the additional investment will be used.

Local health and care systems now have the task of translating that vision into reality. Across England, sustainability and transformation partnerships and integrated care systems are currently preparing 5-year implementation plans setting out how they will deliver the plan in their local communities.

To help this work, the Health Foundation has produced a new analysis which examines in detail the financial, activity and workforce implications of The NHS long term plan, as well as the key issues with which local systems will need to grapple.

At the heart of The NHS long term plan lies a new service model designed to turbo-charge primary and community care and in turn enable more people to live better and healthier lives in their community. This approach commands widespread support, not least because it offers at least the prospect of starting to manage the pervasive pressure of rising demand and the possibility of creating sustainable services.

Delivering this will be central to the success of the plan. The proposed investment in primary and community services needs to break the transactional treadmill that leads to an acute sector that constantly struggles to cope. However, the briefing sets out that we should not be under any illusion about the scale of the task – achieving this without a front-loaded financial settlement will not be easy. The service will need to draw on all the learning and knowledge available about how best to do this.

The briefing also highlights the unfinished business of the funding settlement. The delivery of The NHS long term plan depends on supporting investment in capital, public health, workforce education and training and in social care. The additional funding announced last year specifically excluded all these elements and it is vital the promise is kept, and this year’s spending review addresses them.

The effects of a prolonged period of underinvestment in these areas is now more apparent than ever.

- Buildings, equipment and digital technology are all urgently in need of capital investment to enable the delivery of modern and efficient health and care services.

- The impact on some of the most vulnerable citizens of the social care crisis is hard to overstate and it will continue to damage primary, community and hospital services.

- With a significant shortfall of more than 100,000 posts the case for increased resources for education and training is compelling.

- Likewise, the cuts to public health services such as smoking cessation, sexual health and drug and alcohol services have simply left more costs at the doors of the NHS and have left thousands of patients damaged in ways that could have been avoided.

The health service has welcomed the additional funding it has received and acknowledges that this is in sharp contrast to other parts of the public service. But delivering the service change needed will not be easy and expectations of what can be delivered should be tempered. Above all though this briefing is a powerful reminder to government that success will depend on whether it is willing to complete the investment that the health and care system needs. Without it the delivery of The NHS long term plan has to be in doubt.

Niall Dickson

Chief Executive of NHS Confederation

Introduction

NHS funding has grown by an average of 3.7% per year in real terms over its 70-year history. Following the 2008 global financial crisis, and the resulting response from the Coalition and Conservative governments to reduce public spending, this spending growth slowed considerably, growing at less than half the rate since 2009/10 – more slowly than in any comparable period since the NHS was founded.

Table 1: Annual average real growth rates in UK public spending on health care, selected periods

|

Period |

Financial years |

Average annual real growth rate (%) |

|

Pre-1979 |

1949/50 to 1978/79 |

3.5 |

|

Thatcher and Major Conservative governments |

1978/79 to 1996/97 |

3.3 |

|

Blair and Brown Labour governments |

1996/97 to 2009/10 |

6.0 |

|

Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government |

2009/10 to 2014/15 |

1.1 |

|

Cameron and May Conservative governments |

2014/15 to 2018/19 |

2.3 |

|

Whole period |

1949/50 to 2018/19 |

3.7 |

Source: Nominal health spending data from Office of Health Economics (1949/50 to 1990/91), HM Treasury Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (1991/92 to 2016/17), and HM Treasury Supplementary Estimates (planned 2018/19). Real spending refers to 2019/20 prices, using the GDP deflator from the HM Treasury, March 2019.

Since 2009/10, pressure has mounted, hospitals are in deficit and waiting times have risen markedly. Increasingly, funding has focused on day-to-day spending at the expense of investment in public health, education and training, and capital budgets. Funding for day-to-day services is allocated from the government to NHS England; the Department of Health and Social Care has a separate budget for investment in education and training, public health and capital. The Spending Review 2015 attempted to redefine ‘NHS’ as NHS England’s budget, allowing increases in NHS England’s budget to be partially offset by real-terms decreases elsewhere across the overall NHS budget.

In June 2018, the Prime Minister announced that NHS England’s funding would grow by an average of 3.4% per year in real terms for the next 5 years. At the time, the cash-terms commitment would increase funding from £114.6bn in 2018/19 to £135.1bn in 2023/24 – an increase of £20.5bn in real terms, in 2018/19 prices. However, the remainder of the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget has not yet been set for 2020/21 and beyond, and is to be decided as part of the next Spending Review. This includes investment in public health, education and training, and capital budgets.

Although the Department of Health and Social Care has policy responsibility for social care, the budget arrangements for adult social care are different. Adult social care services are the responsibility of local government and are funded from a mix of national grants, local funding from council tax, and business rates and transfers from the NHS budget through the Better Care Fund. Recent years have seen an increase in public funding for social care, however, while NHS funding was protected in the spending restrictions following the financial crisis, social care was not. Funding for social care actually fell from £18.6bn in 2009/10 (by almost 2% per year) throughout the term of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition government after a peak in 2010/11. Since 2014/15, spending has recovered to similar levels to 2009/10 with a planned budget of £18.6bn in 2018/19. However, in this time the population in England has grown and aged, consequently placing the social care system under increased pressure.

Table 2: Annual average real growth rates in English public spending on adult social care, selected periods

|

Period |

Financial years |

Average annual real growth rate (%) |

|

Blair and Brown Labour governments |

1996/97 to 2009/10 |

6.0 |

|

Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government |

2009/10 to 2014/15 |

-1.9 |

|

Cameron and May Conservative governments |

2014/15 to 2018/19 |

3.1 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Adult Social Care Activity and Finance Report: Detailed Analysis England 2017–18 and Personal Social Services: Expenditure and Unit Costs, England – 2012–13, Provisional release.

The next Spending Review will determine councils’ spending power for adult social care. But with these decisions delayed, adult social care continues to be overlooked, with no date for the government's long-promised social care green paper and no funding reform anticipated.

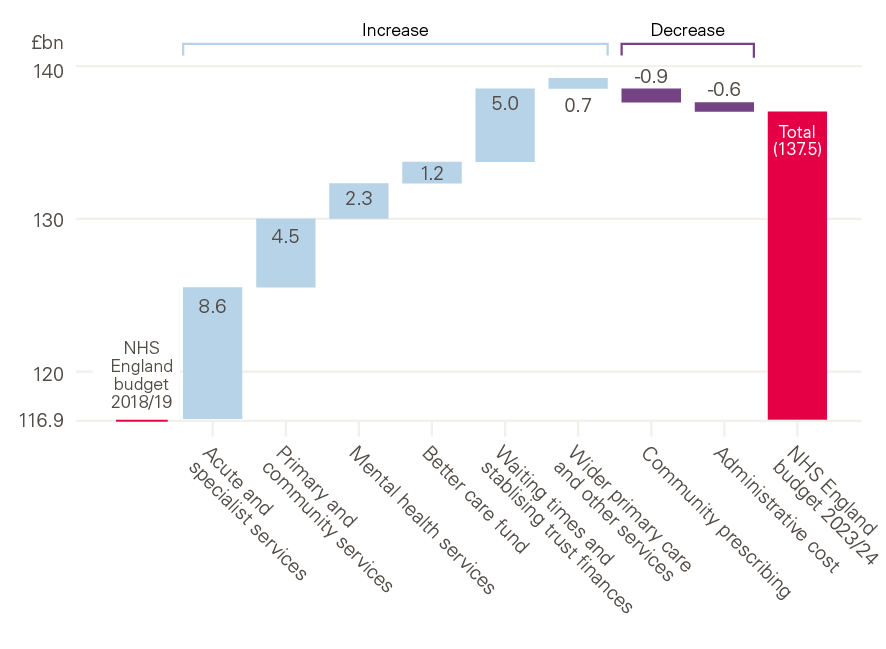

The long-term plan settlement

In current (2019/20) prices, the average real-terms funding increase for NHS England announced by the Prime Minister in June 2018 will increase its funding from £116.9bn in 2018/19 to £137.5bn in 2023/24 – an increase of £20.6bn. The NHS long term plan confirms this ambition.

In the 2018 Autumn Budget, HM Treasury made it clear that ‘the government will confirm the final settlement consistent with [The NHS long term plan], and the £20.5bn real-terms increase by 2023/24, by Spending Review 2019’. Alongside The NHS long term plan, NHS England set out this settlement in cash terms. The exact real-terms increase that it equates to will change as estimates of future inflation change (these are officially updated 6 times per year); the latest estimates released by HM Treasury imply an increase for NHS England of 3.3% per year in real terms, due to projections of inflation being slightly higher. This does not include the cost of meeting any pressures on the health budget from additional pension costs, which will be met by a reserve held by HM Treasury and are expected to cost around £2.85bn this year.

However, the profile of this spending has changed since the Prime Minister’s initial announcement. The publication of The NHS long term plan in January 2019 and subsequent changes to expected inflation mean that the second year of growth will be 3.2% rather than 3.6%, and the final year of growth will be 4.0% rather than 3.4%. This essentially means that the budget for NHS England is expected to be lower in all but the final year than what was announced in the Prime Minister's NHS funding announcement (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Phasing of real-terms growth in NHS England’s budget

Source: HM Treasury; NHS England.

Shifting the balance of funding

The NHS long term plan sets out ambitions to improve NHS care and outcomes, and allocates funding to achieve those ambitions. The aim of the plan is to shift the NHS model of care further upstream: more preventive care, closer integration of services in the community for people with chronic conditions, better coordination of urgent care to reduce demand on emergency departments and outpatient visits reduced by a third. Improvements are promised in priority services, including mental health, maternity and cancer, and there is an emphasis on the NHS’s role in tackling health inequalities.

The plan explicitly commits to increasing spending in two areas: mental health, and primary and community care. For mental health it confirms that ‘mental health services will grow faster than the overall NHS budget, creating a new ringfenced local investment fund worth at least £2.3bn per year by 2023/24’. Primary medical and community services are also ‘guaranteed’ to grow faster than the overall NHS budget. This creates a ‘ringfenced local growth fund worth at least an extra £4.5bn per year in real terms by 2023/24’.

There are other costs that will need to be met within the additional £20.6bn of funding. One such cost is associated with the ongoing review by the national medical director into clinical standards. While this review is not yet completed, we have assumed that the cost of accepting its recommendations will be broadly cost-neutral compared with the cost of meeting current NHS constitutional standards. Finally, the plan commits to providers and commissioners reaching financial balance. This is likely to cost around £2bn – the amount reported by NHS Improvement as the net ‘underlying deficit’ in the sector as well as a portion of the Provider Sustainability Fund. Without committing this spending, whether directly to trusts or through the tariff, the provider sector will remain in deficit.

The plan confirms that the NHS needs to deliver annual productivity gains of 1.1% per year over the next 5 years, but also builds in a further £600m (in 2019/20 prices) of administrative savings over and above productivity savings.

Figure 2: Planned and assumed allocation of NHS England funding growth 2018/19 to 2023/24

Source: Authors' calculations; The NHS long term plan; NHS England board papers and accounts.

What care will the extra funding buy?

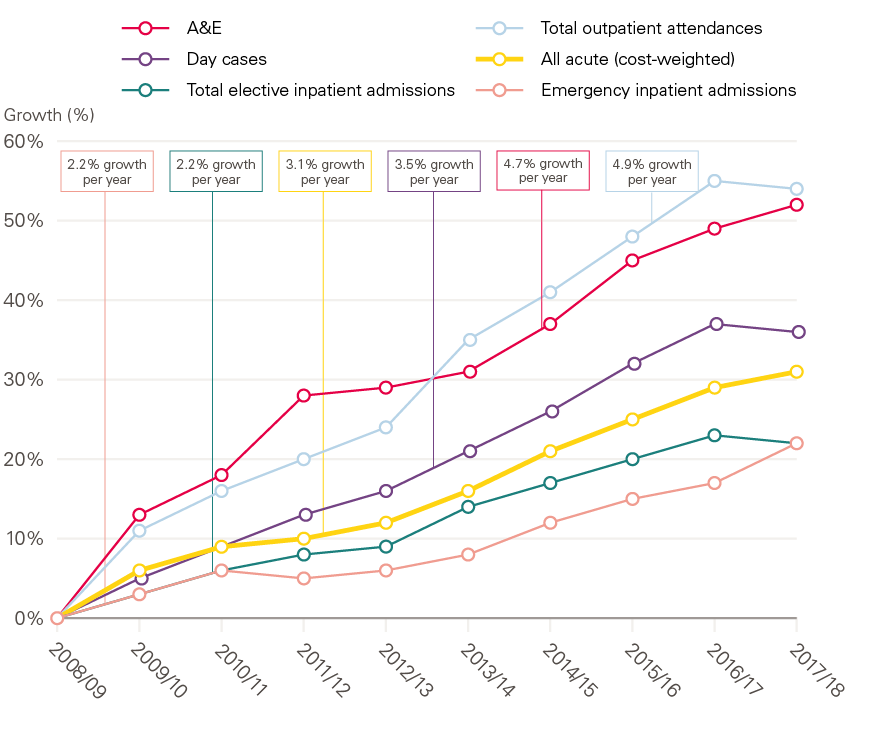

Since 2008/09 activity in acute services has grown by 3.1% per year on average (as shown in Figure 3). But acute activity is made up of a number of different components. This overall rise includes increases of more than 50% in outpatient and A&E attendances. Even areas of relatively slower growth, such as elective and emergency inpatient admissions, have increased by more than 20% over the last decade (2.2% per year on average).

Figure 3: Growth in components of acute activity since 2008/09

Source: Hospital Episode Statistics (HES).

As specified in The NHS long term plan, between 2018/19 and 2023/24 funding will grow faster than the overall NHS England budget for mental health (4.6% per year, on average), and primary medical and community services (3.8% per year, on average). This means that funding for other services will need to grow at a slower rate (3.0% per year, on average). The level of funding for different areas of care determines how much activity (units of care) a service is able to provide, given a certain level of productivity and growth in costs such as pay.

There is a consensus around the benefits of moving the balance of care away from the acute sector when that care can, and should, be provided in the community. Recent policy has focused on this, ‘with the aim of providing better health care for patients, cutting the number of unplanned bed days in hospitals and reducing net costs’. However, as this paper and other evaluations report, the evidence is mixed on the impact that this can have on avoiding acute admissions and reducing costs. There are examples of where commissioners have successfully moderated demand for acute care. For example, in Ruschliffe, Nottinghamshire, a package of enhanced support for residents in nursing and care homes was linked to a 23% reduction in emergency admissions when compared with a control group. However, the success of schemes like this require sustained investment of time and resources, as well as careful evaluation to ensure they do not result in unintended consequences. Similarly, not all interventions are successful in moderating demand (and some may increase demand, although they may be worthwhile in other ways) and so expectations around the ability of the NHS to moderate acute demand at scale and pace should be based on realistic assumptions, informed by this mixed evidence base.

Even if implemented successfully at scale, this change will take time and is unlikely to be able to fundamentally change the growth of acute activity over the next 4 years. Therefore, for services provided by acute and specialist hospitals (the largest single area of spending in the NHS) this relatively lower funding growth will present a real challenge as it will have implications for how much activity can be provided.

The amount of activity that can be undertaken within a given budget is critically dependent on pay. The latest pay deal for Agenda for Change staff means that pay for most NHS staff will rise in real terms until 2020/21. Beyond that point, we've assumed that, in order to recruit and retain staff, pay will not fall behind earnings growth in other sectors and across the economy as a whole.

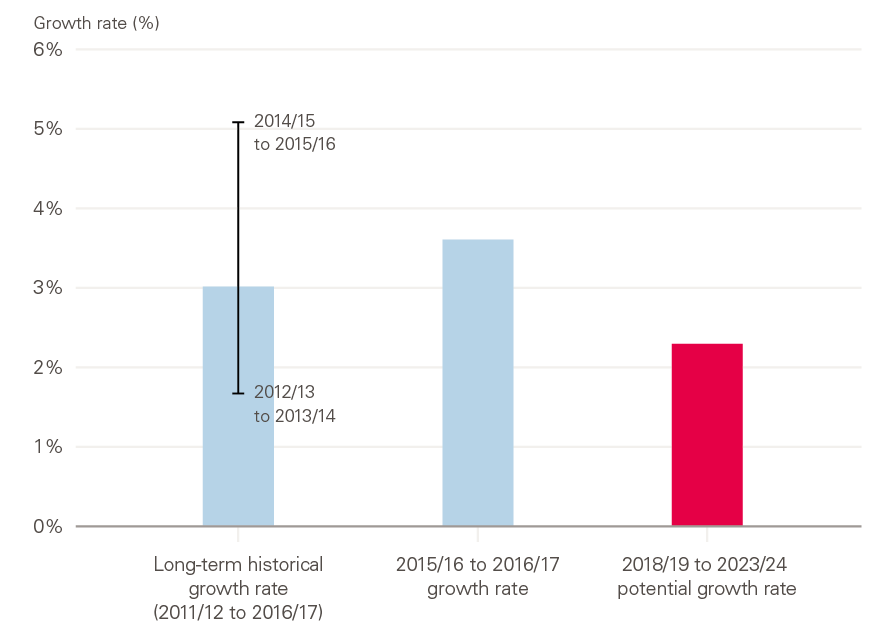

If acute funding grows in line with the remainder of the budget (excluding mental health, and primary and community services) over the next 5 years, acute activity will be able to grow at an average annual rate of 1.6%. As set out in Figure 4, this is just half the historic rate.

If other areas of spending (such as prescribing) grow more slowly, as set out in Figure 2, then acute activity growth would be 2.3%. On prescribing, this is would be partly driven by switching to generics as well as the latest reimbursement scheme with industry. Under this scenario, NHS providers would achieve 1.1% productivity growth per year and NHS staff earnings would rise in line with the wider economy after the current pay deal to prevent deterioration in recruitment, retention and engagement. This is still significantly below the rate that acute care has grown by over recent years (see Figure 4). If pay growth is lower, this may allow acute and specialist activity to grow at a rate similar to that of recent years. However, it would create a substantial new challenge and it is hard to see how the NHS could successfully recruit and retain sufficient numbers of staff if it chooses to return to the low (relative to the rest of the economy) pay growth of recent years.

Figure 4: Estimated acute activity growth and recent growth rates from The NHS long term plan

Source: Authors' calculations; Castelli et al. Productivity of the English National Health Service: 2015/16. University of York; 2018.

Either scenario represents a significant moderation of acute activity growth, compared with the most recent year for which we have good data (3.6% between 2015/16 and 2016/17). It would also be below the levels of historical and future acute activity pressures (around 2.5%) reported by NHS England in their recap on the Five year forward view. This estimate combines demographic (the change in the population by age and sex) analysis and non-demographic assumptions (using historic activity trends). Similarly, work by the IFS and the Health Foundation suggested that, just to maintain services at their current quality, acute activity in England needs to grow by 2.7%.

Therefore, moderating acute activity growth to between 1.6% and 2.3% is a substantial challenge; it represents a slowdown of between a half and a quarter compared with the long-term average.

Even small shifts in activity growth make a big difference in a system the size of the NHS. In 2017/18, there were around 8.6 million elective admissions, one of the components of acute care. If acute and specialist activity grows at 2.3% a year from 2018/19, it will reach 9.6 million by 2023/24. This is 300,000 admissions fewer than if activity grows at 3.0%, and 600,000 fewer than if it grows at 3.6%.

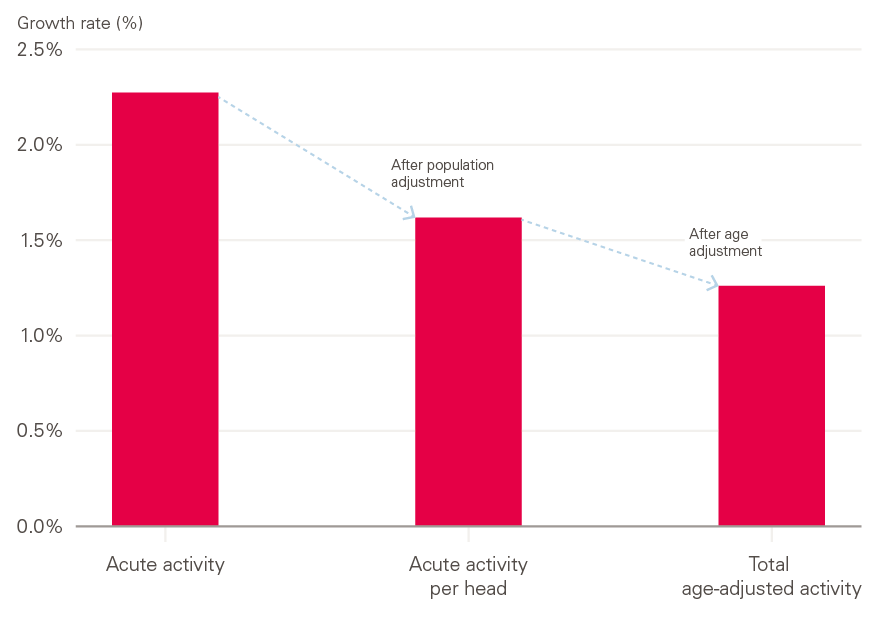

Due to population growth, this projected acute activity growth of 2.3% per year is a per person growth rate of 1.6%. Although population growth for all ages is fairly low, the population is ageing. Once accounting for the ageing population, the per person average annual growth rate is just 1.3% (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Breakdown of acute activity pressures 2018/19 to 2023/24

Source: Authors' calculations, ONS population projections.

If the NHS is unable to moderate acute activity growth then there will be major ramifications for other areas of care. If acute activity continues to grow at the 3.6% seen recently, an increase of £13.0bn will be needed for acute services alone – that is £4.1bn more than would be provided if the NHS were able to successfully constrain acute activity growth to 2.3%, and £6.8bn more than if the NHS were able to moderate acute activity growth to 1.6%.

This £6.8bn would be almost all of the value of the real-terms commitments for mental health, and primary and community services combined.

Workforce

Any increase in activity has major implications for the workforce. And, in order for the NHS to be able to slow the rate of growth in acute activity, the NHS will need to boost the available workforce in non-acute settings. The workforce challenges in the NHS in England now present a greater threat to health services than the funding challenges, and urgent action is now required to avoid a vicious cycle of growing shortages and declining quality of care. This is recognised in The NHS long term plan, which makes clear ‘To make [the] long term plan a reality, the NHS will need more staff, working in rewarding jobs and a more supportive culture’.

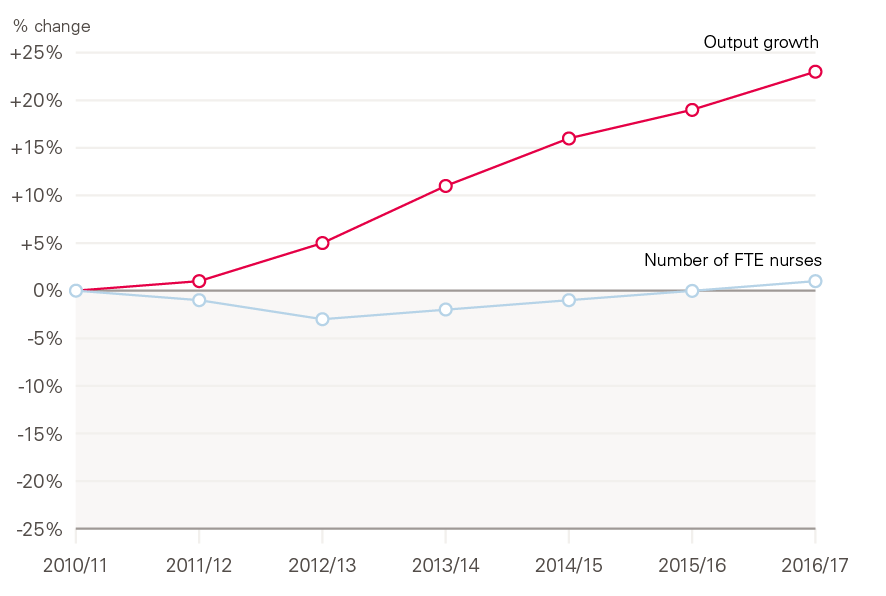

While productivity improvements can allow activity to rise faster than staff numbers, it is clear that staff in the NHS are stretched. Between 2010/11 and 2016/17 output in hospital and community health services grew by almost a quarter (23%), while the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) nurses grew by just 1% (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Service output and FTE nursing staff numbers in the NHS Hospital and Community Health Service 2010/11 to 2016/17

Source: NHS Digital, NHS Workforce Statistics; ONS, Public service productivity: healthcare, England.

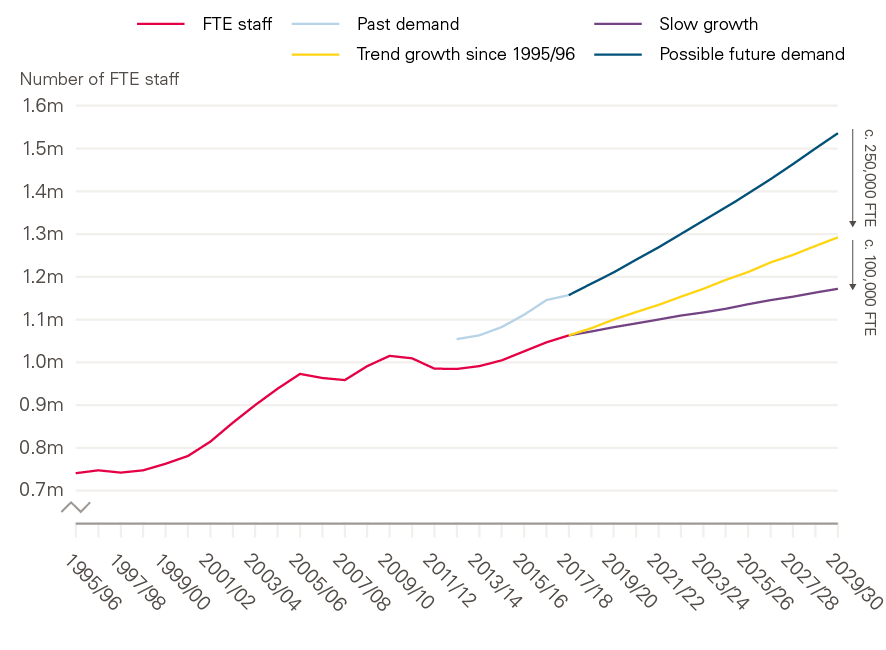

The NHS is currently short of more than 100,000 FTE staff in trusts. Our projections with The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust suggest that this could more than double to almost 250,000 in the next decade as the demand for staff increases year-on-year due to demographic change and the increasing prevalence of chronic conditions (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Future supply of and demand for NHS staff, 1995/96 to 2029/30

Source: The health workforce in England: Make or break; Health Foundation projections, based on workforce data from NHS Digital and Health Education England.

These problems are particularly severe in nursing. Our recent projections with The King's Fund and the Nuffield Trust suggest that by 2023/24, the NHS will not be able to close the gap between demand and supply for nurses working in hospitals, mental health and community trusts (see Figure 8). Without immediate policy action, the shortages in nursing could double to 70,000 FTE nurses. Even with policy action, the gap in 2023/24 would be around 40,000 FTE nurses – 7,500 more than in 2018/19. This is before any impact of recruiting nurses internationally. In order to halve nurse vacancy levels to 5%, the NHS will need to recruit 5,000 FTE nurses from abroad each year to 2023/24 – three times more than current levels.

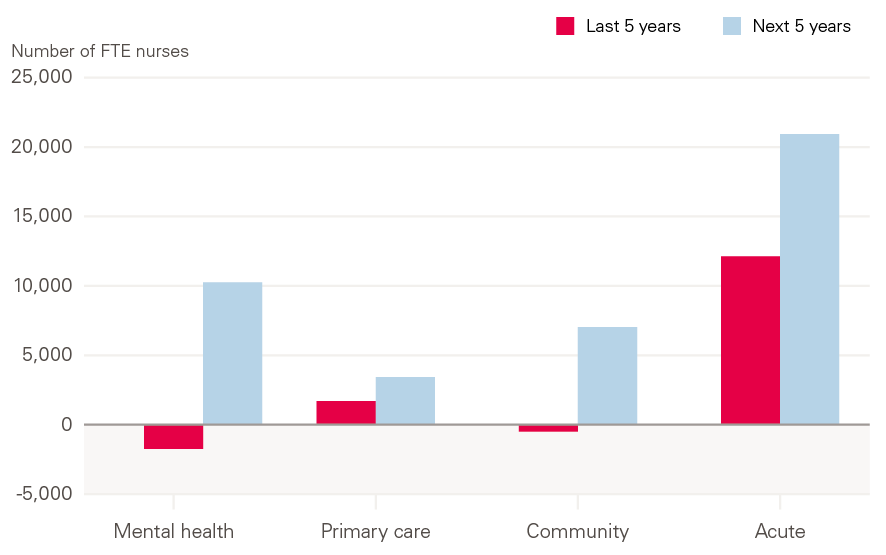

Problems are particularly severe in mental health and community settings. While The NHS long term plan’s ambition is to provide more care outside of acute settings, and moderate the amount of acute activity, it will not be possible to safely or effectively increase the amount of care delivered in these settings without the staff to provide it. This is exacerbated by the very low level of growth (and in some cases reductions) in staff numbers outside of acute settings in recent years.

Figure 8: Projected nurse demand and supply in NHS trusts, 2018/19 and 2023/24

Source: Beech J, Bottery S, Charlesworth A, Evans H, Gershlick B, Hemmings N et al. Closing the gap: Key areas for action on the health and care workforce. Nuffield Trust; 2019.

Note: Chart shows demand after the impact of improved productivity. As a result, demand is lower (by 3,500 in 2023/24) than is likely given current trends, as presented in the report.

Figure 9: Change in FTE nursing staff numbers in NHS trusts and general practice relative to 2018/19

Source: NHS Digital. NHS Workforce Statistics.Note: Figures for primary care nurses in 2013/14 are extrapolated from current growth rates. ‘Acute’ refers to nurses working in Acute, General and Elderly care; ‘Community’ refers to nurses working in community services, but does not include health visitors, school nurses, or community learning disability and mental health. Does not include staff working for independent sector providers.

In mental health, if staff numbers grow in line with activity, this would require an additional 10,300 nurses working in mental health in NHS trusts by 2023/24. This is compared with the reduction of 1,700 mental health nurses in this setting seen since 2013/14 (as shown in Figure 9).

If nurse numbers grow in line with activity in primary care, this would require an additional 3,400 nurses working in primary care, 1,300 more than the level of growth seen over the past 5 years. In community services, an additional 7,000 nurses working in community health in NHS trusts would be required by 2023/24 compared with a reduction of 500 over the past 5 years.

† These figures are £114.6bn, £135.1bn and £20.5bn in 2018/19 prices and under the original settlement. In this briefing, numbers are given in 2019/20 prices using March 2019 deflators for consistency. As a result, some numbers may not match those in official announcements made in 2018/19.

Health spending outside the NHS England budget

While NHS England’s funding to 2023/24 has been agreed, this is not true of all areas of health spending. In the Spending Review 2015, the government attempted to redefine ‘NHS’ as NHS England’s budget, allowing increases in NHS England’s budget to be partially offset by real-terms decreases elsewhere in the overall health budget. This narrower measure of health spending is not consistent with that used by previous governments and is not endorsed by the Health and Social Care Select Committee. The entire Department of Health and Social Care budget remains the best way of measuring health spending, as it provides the full picture of resources available for patient care.

Around a tenth of health spending is allocated in the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget for activities, including: capital investment in infrastructure such as buildings and diagnostic equipment, investment in education, training and development of staff, and the public health grant to local authorities.

Whether the ambitions in The NHS long term plan are deliverable will depend on spending decisions in these areas. Insufficient investment in training, public health and capital infrastructure risks making the changes needed to divert activity away from the acute sector harder to achieve. The timing of these decisions is also important. If these areas of spending have to continue to deal with short-term funding settlements, it impairs the ability to plan and invest, and increases the scale of the challenge to deliver The NHS long term plan.

Staffing is the make-or-break issue for the NHS in England and workforce shortages are already having a direct impact on patient care and staff experience. The NHS long term plan makes it clear that ‘the NHS will need more staff, working in rewarding jobs and a more supportive culture’. However, spending on the education, training and development of staff sits outside NHS England’s budget. It is spending in these areas that will determine if there are enough staff in training, and if they have sufficient levels of investment in their development.

Likewise, just as the earlier NHS Five year forward view depended on a ‘radical upgrade of public health and prevention’, so does The NHS long term plan. While NHS England’s budget can be used to treat people once they are sick, investment in the prevention of poor health can do much more to support people to not need treatment in the first place. The public health grant is spent on services such as sexual health services, smoking cessation, and drug and alcohol services, which have traditionally formed a core part of the NHS. Without investment in areas such as these, pressures on the NHS will increase and the health of the population will be negatively impacted – not just in the long run, but now as well.

Equally, there is growing evidence that the lack of investment in capital is having a negative impact on patient care. Directors and managers interviewed at NHS trusts revealed serious concerns that spending restrictions are impacting service efficiency and, in several cases, the quality of patient care.

All these areas clearly and directly impact patient care and the health of the population. They are as much a part of the health budget as NHS England’s resource budget and, without proper investment, there is a real risk that The NHS long term plan will remain a wish list.

Education and training

One of the largest areas of the wider health budget is spending on education and training, via Health Education England. In 2019/20, Health Education England’s budget for education and training is planned to be £4.2bn; over £1bn less in real terms than the budget Health Education England received in 2013/14 (at £5.3bn). This budget covers the costs of education and training (for example, a contribution to the salary costs of doctors in training and clinical placements) and development (for example, CPD courses undertaken by NHS staff). Some of this reduction is due to Health Education England no longer paying bursary costs for new nursing students, but reductions in areas such as the national budget for workforce development (where spending has been cut by three-quarters between 2013/14 and 2018/19) have also had an impact. This cut will need to be restored if the NHS is going to make progress in not just retaining staff but also supporting them to develop and progress towards more team-based, multidisciplinary working. This is reflected in the People Plan’s aim of ‘achieving a phased restoration, over the next 5 years, of previous funding levels for CPD’.

The supply of nurses

There are particular issues with shortages in the number of nurses working within the NHS. In order to reduce these shortages, there needs to be a significant expansion in the number of nurses in training, and a reduction in the rate of attrition from nursing courses. It is therefore essential to address the key cause of nursing student attrition: the financial problems they face while studying.

Financial problems are a key issue for nursing students during training; the time demands of clinical placements make it hard for students to take part-time paid work alongside full-time study. The current loan system provides means-tested maintenance loans to cover living costs, but the maximum loan is just £8,430 per year (outside London). Finances are by far the most significant concern for students and the number one factor cited by students for the high rate of attrition during training. This is a particular issue for mature students, where the largest drop-off in nursing undergraduates since the abolition of bursaries has been seen. Alongside the current means-tested loan scheme, the recent Closing the gap report from the Health Foundation, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust recommended that a ‘cost-of-living grant’ is introduced for all those studying for a nursing degree. The grant (set at around £5,200 per year) would provide trainee nurses on the maximum loan with an income equivalent to the national living wage and would recognise the impact of the time spent on clinical placements on the scope for nurses to work part-time.

In addition to this, the report proposes that the number of students studying nursing as a postgraduate is substantially expanded. To make postgraduate routes more attractive to students, it recommended that they are made exempt from charging tuition fees. Together these would cost Health Education England up to £560m in 2023/24 (see Table 3). This is around half the reduction in Health Education England’s budget resulting from the reforms to nurse and allied health professional student financing, which abolished the bursary and made them eligible for tuition fees.

The restoration of the workforce development budget and cost-of-living grants for nurses are the largest areas of investment required in order to improve the supply and engagement of staff. Other areas are set out in Closing the gap.

Table 3: Estimated additional funding pressures for Health Education England resulting from the specific new policy measures to reduce the gap between the demand for and supply of NHS nurses and GPs in England

|

Funding requirement (£m, 2019/20 prices) |

||||

|

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

2023/24 |

|

|

Workforce development |

190 |

200 |

210 |

230 |

|

Cost-of-living grants for nurses |

330 |

360 |

400 |

420 |

|

Other funding support for nurses (tuition fees for postgraduates, placement costs) |

40 |

60 |

110 |

140 |

|

Other |

60 |

80 |

90 |

90 |

|

Total additional cost |

620 |

700 |

810 |

870 |

Source: Beech et al. Closing the gap: Key areas for action on the health and care workforce. Nuffield Trust; 2019.

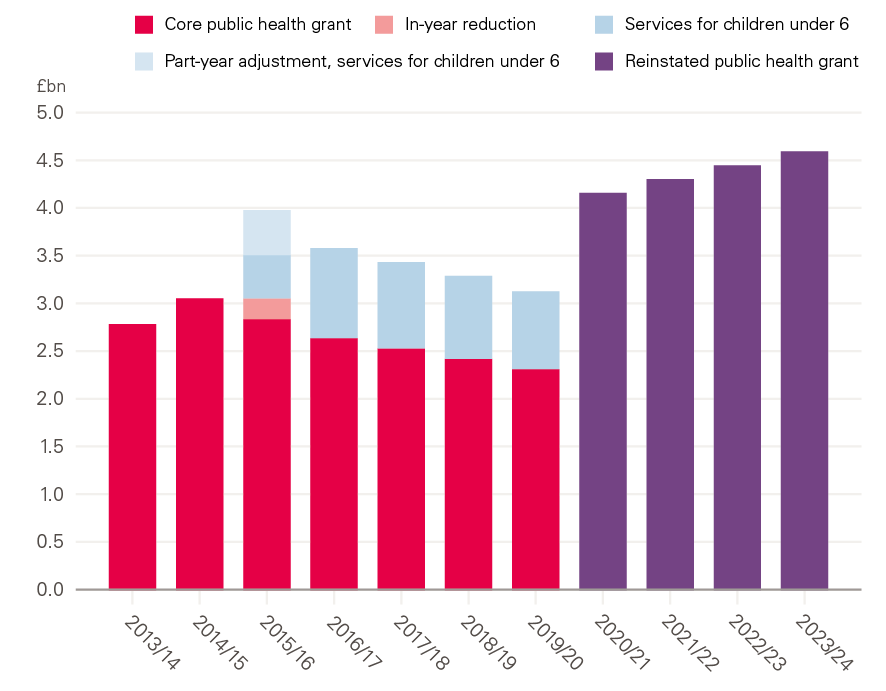

The NHS long term plan sets out that ‘action by the NHS [on prevention] is a complement to, but cannot be a substitute for, the important role for local government’. Progress on public health and prevention relies on adequate levels of funding for local authorities. Likewise, 2019 marks the final year of the Five year forward view, which called for a ‘radical upgrade in prevention’, while the government’s 2018 ‘vision for putting prevention at the heart of the nation’s health’ highlighted the important role of local government in improving health.

Over the past decade of austerity, the ability of councils to maintain and improve the health of their residents has been jeopardised by substantial cuts to local services and investments, many of which directly affect health. Local authority budgets (excluding social care) will have fallen by 56.3% between 2010/11 and 2019/20. And these cuts have not been felt equally: local government spending per person on services in the most deprived fifth of councils has fallen from 1.52 times to 1.25 times the level in the least deprived fifth between 2009/10 and 2017/18.

The public health grant allows local authorities to provide services that maintain and improve people’s health, but this has been reduced in real terms since 2014/15. In fact, in 2019/20 the grant had been reduced in value by £850m in real terms compared with initial allocations for 2015/16. That includes £750m in cuts to spending on the core services transferred to local authorities in 2013/14, and £100m in cuts to services for children under six: a responsibility transferred to local authorities fully in 2016/17 (the spend attached to these additional services can mask the scale of the cuts). The change in the grant, which now stands at £3.1bn for 2019/20, equates to a reduction of almost a quarter (23%) in real spending power on a per person basis between 2014/15 and 2019/20. While future plans are uncertain, when set out in December 2018, the notional spend for 2020/21 was flat in cash terms, which would reduce that per person spending power by a further 2%.

Figure 10: Annual public health grant net expenditure between 2013/14 and 2019/20 in real terms, and the cost of reinstating the public health grant

Source: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government; Department of Health and Social Care.

These funding cuts come at a time when key indicators of health are causing concern. Mortality improvements have slowed and there are large inequalities in health outcomes between local areas. For example, there is a gap of 18.4 years in healthy life expectancy for women in England’s 10% most- and least-deprived areas. Despite this, the areas of greatest need have not been protected from funding cuts. The lack of strategic approach, coupled with real-terms cuts, risks widening health inequalities at a time when the government has pledged to tackle such injustices.

Reversing the real-terms, per capita cuts would require just over £1bn of additional investment next year relative to the previously announced provisional baseline. This would mean the public health grant in 2020/21 would be £4.2bn, returning both the core public health grant and services to children under 6 back to their previous per capita levels. Looking forward, under the assumption that the grant then grows in line with increases to NHS England’s budget, so that the public health grant is maintained relative to NHS England spending, would mean providing a further real-terms boost to funding of £1.5bn by 2023/24, taking the grant up to a total of £4.6bn a year. At a minimum, the government should aim to achieve this level of funding by 2023/24, with above-real-terms increases in the grant allocated to the most deprived areas experiencing the greatest health problems and the additional funding phased in over the next 4 years.

However, there is a strong case that public health spending should be increased further. Rather than the additional investment called for in the Five year forward view, spending has been cut. Even the additional investment by 2023/24 outlined above would fall short of the over £3bn per year of additional investment relative to the current grant that we have previously estimated is required so that the grant is distributed to best meet local needs while ensuring that no local areas experience a reduction in spending. Questions also remain about the extent to which public health funding will be sourced from business rates, and how that funding will be allocated across local authorities. Going forward, even if council tax were to be increased every year by the same amount as this year, adult social care could account for more than half of revenues from council tax and business rates by the mid-2030s. This would leave little left for public health and other services.12

Capital spending

Alongside the day-to-day funding set out above, investment in capital is urgently required. The capital budget of the Department of Health and Social Care is used to finance long-term investments in the NHS, such as new buildings, technology, IT, and research and development. Capital spending can support the improvements in productivity and diagnostics that are needed to make goals of The NHS long term plan deliverable – but also years of neglect have left the NHS estate in need of urgent upkeep. While the revenue budget has seen low growth in each year since 2010/11, the capital budget has seen multiple years of falls in funding, with significant decreases in capital funding in 2015/16 and 2016/17. Most of the fall in the capital budget can be explained by transfers to the revenue budget, which have totalled more than £5bn since 2014/15. The Department of Health and Social Care has stated its goal to end these transfers after 2019/20. While the Autumn 2018 budget planned for a large increase in the 2019/20 capital budget to £6.7bn, the most recent plans estimate a 3% decrease in the capital budget, with a fall to £5.9bn from £6.1bn in 2018/19.

Of the 2017/18 capital budget, 58% was spent in NHS trusts and 21% on research and development, with the remaining portion spent by the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England on other central programmes, such as investment in primary care, community and social care.

In recent years, the UK has fallen well behind comparable countries on capital spending in health care as a share of GDP. From the most recent data, in 2016, the UK spent 0.27% of GDP on capital in health care, compared with 0.51% in comparable countries.

While capital to revenue transfers have contributed to a falling capital budget, they do not explain most of the difference between the UK and the average from other countries, at most bringing the UK up to approximately 0.3% of GDP. Similarly, the UK is far behind all OECD countries in the level of MRI and CT scanners per head, with less than a third the rate of Germany. These low levels of scanning equipment will make it difficult to achieve some of the goals outlined in The NHS long term plan, such as improving early diagnosis rates of cancer. Bringing the UK up to the average number of MRI and CT scanners would require more than £1.5bn in extra capital spending.

Figure 11: Fixed capital formation in health care, 2000–16, OECD countries

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for OECD countries for which data for all years were available: Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Norway, Sweden and USA.

Declines in the Department of Health and Social Care capital budget have led to sharp falls in capital spending by NHS trusts, which has fallen by 21% since 2010/11. This has led to the total value of capital per worker in trusts reducing by 17% between 2010/11 and 2017/18. This has left trusts with a growing maintenance backlog of over £6bn in 2017/18, rising every year since 2013/14. More than half of this backlog is now a high or significant risk (the two highest risk categories). Qualitative evidence found that trusts are unable to afford the most modern technology while also using equipment far beyond their expected useful lives due to budget constraints. Some trusts have also abandoned long-term transformation projects due to the uncertainty around long-term capital funding and the need to address issues related to patient safety.

Capital to revenue transfers have created an environment of short-termism, leaving significant uncertainty around capital funding, which requires spending on projects over multiple years. Further, the Autumn 2018 budget announced the end of new private finance initiative contracts, which create a gap in future funding, placing further pressure on the Department of Health and Social Care’s capital budget. Concerningly, trusts have been told to review their capital plans and defer non-essential spending that has already been committed into later years. This continues a cycle of short-term funding, making it difficult for trusts to plan for long-term transformation and improvement to their estates and facilities.

The Department of Health and Social Care has outlined a vision to be a world leader in digital, data and technology in health and care. While new technologies have the possibility to transform patient care, and improve productivity, without a long-term commitment and significant increase to capital funding, this will be difficult. Current capital budgets have been insufficient, leading to declining spending in trusts, rising and high-risk maintenance backlogs, and ageing IT systems across the NHS.

Figure 12: Projected capital budgets based on NHS England long-term settlement growth rate

Source: Department of Health and Social Care Accounts; OECD.

For the NHS in England to match the OECD average in capital spending, a capital budget of £9.6bn in 2019/20, rising to £10.3bn in 2023/24 would be needed. Figure 12 plots alternative scenarios for future capital budgets: first, the 2019/20 budget held constant in real terms; second, the capital budget growing in line with the long-term funding settlement for NHS England; and third, the capital budget incrementally increasing to the OECD average by 2023/24. Matching the OECD average would require careful management of the capital budget to ensure that funding was directed to areas of need, such as the maintenance backlog, more MRI and CT scanners, and investments in other new technology to improve productivity. Among EU15 and G7 countries, the UK has the lowest number of CT and MRI scanners per capita. Low levels of diagnostic equipment threaten the ability of the NHS to improve care in line with commitments made in The NHS long term plan (for example, new rapid diagnostic centres to improve early diagnosis of cancer). Increased capital spending is also likely to incur more revenue spending from the costs associated with using the capital, such as increased costs of the workforce. Additionally, some capital spending such as IT, may increasingly become a part of the revenue budget.

Implications for the Department’s budget

These areas – education and training, public health, and capital – are no less a part of health spending than NHS England’s budget, and it is only due to the redefinition of health spending made in the Spending Review 2015 that their settlement is not concurrent with NHS England’s. Funding NHS England in line with rising demand and cost pressures is important, but the ability to achieve the full ambitions of The NHS long term plan relies on these other areas of health spending.

If areas outside NHS England’s budget grow just in line with inflation, then the Department of Health and Social Care’s budget will increase from £139bn to £155bn over the next 5 years. This would see total health spending grow at a rate of just 2.9% per year – below the level required to maintain current standards of care. Under this scenario, other budgets would fail to keep up with growing demand, and the quality of care is likely to deteriorate.

Table 4: Department of Health and Social Care spending under different scenarios

|

Spending (£bn) |

Annual average growth rate (%) |

|||

|

2019/20 |

2023/24 |

|||

|

The NHS long term plan |

NHSE |

121 |

138 |

3.3 |

|

No further funding growth beyond The NHS long term plan |

Resource |

133 |

149 |

3.0 |

|

Total |

139 |

155 |

2.9 |

|

|

Annual funding growth rises in line with NHS England |

Resource, of which |

133 |

152 |

3.4 |

|

HEE |

4 |

5 |

3.4 |

|

|

PH grant |

3 |

4 |

3.4 |

|

|

Capital |

6 |

7 |

3.4 |

|

|

Total |

139 |

159 |

3.4 |

|

|

Further catch-up investment in staff, public health, and capital |

Resource, of which |

133 |

152 |

3.5 |

|

HEE |

4 |

5 |

4.9 |

|

|

PH grant |

3 |

5 |

9.8 |

|

|

Capital |

6 |

10 |

14.7 |

|

|

Total |

139 |

163 |

4.1 |

|

If the Department’s budget were to grow at 3.4% – the real-terms growth rate originally planned for NHS England – it would rise to £159bn (see Table 4). This is roughly in line with estimates from Securing the Future for the funding levels required to maintain current standards of care, given a growing and ageing population and a rising burden of chronic disease. However, it would be below the pressures on the wider health budget. This would mean trade-offs would need to be made. This may mean the staff development budget remains at inadequate levels, or that no further financial support is given to nursing students. The result of either of these scenarios is that the NHS is unlikely to be able to train and retain enough nurses by 2023/24, and staffing shortages may worsen. For the public health grant, it will mean that the grant by 2023/24 is no higher than it was in 2016/17, despite 7 years of growing demand and increases in the costs of delivering care. On capital, the UK is likely to fall further behind comparable countries, and crucial investment in maintenance and diagnostic equipment will not happen.

If the Department’s budget grows in line with the pressures outlined in this paper, total health spending would grow to £163bn. This would be a growth rate of 4.1% per year over the next 5 years. However, when combined with the past 5 years of slow growth, this would be just 3.0% per year over the decade to 2023/24.

Social care

But the NHS is not an island. It is part of a wider health and care system that includes adult social care for people who need care and support. Social care functions very differently to the NHS, with a highly restrictive ‘needs and means’ test. The NHS long term plan was developed with the clear expectation of a sustainable funding settlement for social care, stating that ‘the government … committed to ensure that adult social care funding is such that it does not impose any additional pressure on the NHS over the coming 5 years. That is the basis on which the demand, activity and funding in The NHS long term plan have been assessed’. Investing properly in social care is not just important for the NHS; social care services are relied upon by people for crucial aspects of daily life.

Overall public spending on adult social care in England reached its highest level in real terms in 2010/11. This was also the last time the means test thresholds – which define eligibility for publicly funded social care – were increased. Since then, spending has fallen in real terms, with a recent recovery to around £1bn less than in 2010/11 – £17.8bn in 2017/18 and a planned budget of £18.6bn in 2018/19. In that time, the population in England has aged and grown, with more people living into old age with multiple chronic conditions. The number of working age adults requiring social care for learning disabilities, physical support, sensory support and mental health support is projected to increase by almost 50% by 2040.

This has undoubtedly increased the demand for publicly funded social care. In a recent report, the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) at the London School of Economics has estimated this growth in demand, projecting that publicly funded social care would need to grow by 3.6% between 2015/16 and 2023/24 in order to maintain the same level of care to the same proportion of the population. Planned budgetary increases announced recently imply an increase in real terms social care net expenditure to £19.3bn in 2023/24 – an annual average rate of 1.4% per year from 2017/18.

In addition to local authority core spending, publicly funded social care is funded through the Better Care Fund and the Social Care Precept, as well as the money from central government and the NHS, one-off winter pressures supplement (£240m) and, in 2020/21, the social care grant (£410m between adult and children's social care). These additions provide an extra £4.3bn to social care funding in 2020/21. From 2020/21, we assume that the Better Care Fund and the Social Care Precept are held constant in real terms, while the remainder of the budget grows in line with local authority net current expenditure from the Economic and Fiscal Outlook (March 2019).

Since 2015/16, funding has grown more slowly than projected demand. Unless further productivity gains are made, the number of people receiving publicly funded social care and/or the quality of that care will fall in future. If both demand and productivity increase in line with PSSRU’s projections, the funding gap in 2023/24 will be £2.7bn.

In fact, we have seen a fall in the number of people receiving long-term care to 857,770 in 2017/18. This has been mainly driven by a decrease in people aged 65 and over receiving long-term care, down 22,110 to 565,385 since 2015/16. Falling budgets have led to reduced provision of publicly funded services, with older adult social care activity falling 2% per year on average from 2015/16 to 2017/18. A consistently reduced service has meant that the ‘goal posts’ for funding-gap calculations keep changing, because they are based on ‘maintaining the current service’. For instance, providing the same access and quality of publicly funded social care as in 2015/16 would mean a bigger gap, of £3.9bn.

Pay

Social care is, like the NHS, a service delivered by people. However, pay and benefits are very different. Around two-thirds of staff are paid at the minimum wage, many are on zero-hours contracts, there is a significant reliance on staff recruited from overseas and staff turnover is high. But health and social care nonetheless compete for the same pool of potential workers, including nurses, occupational therapists and support staff.

The NHS is likely to appear increasingly attractive to workers compared with the care sector as a consequence of the recent NHS pay deal, which includes possible pay increases of up to 29% for some staff. This may cause further pay pressures in social care. The NHS exists as part of a local labour market and so local social care providers who try to match NHS pay increases will put more cost pressure on already financially distressed social care providers.

Our estimate suggests that the cost of social care staff receiving a similar uplift to those working in the NHS would be around £1.8bn, once you map current social care staff to equivalent current pay rates in the NHS, leading to a funding gap of £4.4bn in 2023/24. While this is a significant additional cost, it is hard to see how social care providers can recruit and retain staff when salaries are rising higher in competitor labour markets.

How has this been happening?

Access to public funding for social care is based on both need and financial means. If you are in need of social care, the government will provide some financial support if your total wealth (including your house in the case of residential care need) is below the threshold of £23,250. These thresholds have been held constant in cash terms since 2010/11 at a time when house prices and general inflation have been increasing. In real terms, these thresholds have fallen by 11% as a result of no nominal change. This has led to the fall in social care provision at a time when demand is increasing.

To put this in perspective, we also consider the spending levels that would have been required to meet projected demand increases, providing the same access and quality of publicly funded social care as in 2010/11. Funding has been consistently below levels of increasing demand, resulting in an estimated £6bn real-terms funding gap already by 2017/18 and a £10bn gap by 2023/24. This is half the size of the currently planned social care budget. The Dilnot Commission mapped out a plan to cap care costs for older people. This plan has since been postponed indefinitely. Introducing a care cap would add a further £2.8bn to the cost of social care in 2023/24.

Figure 13: Social care funding gap in 2023/24

Source: Authors' calculations, based on PSSRU projections.

What is happening to service users whose care is no longer funded?

Social care is an increasingly politically charged issue. Fully addressing the acknowledged problems has so far proven to be beyond government and those politicians who fear a public backlash when proposing reform of the current system. This has contributed to the lack of long-term funding decisions and a fall in the levels of publicly funded social care delivered.

Due to a lack of available information, it is very difficult to know exactly what happens to those in need of social care, but who don’t meet the means test. But possible outcomes include:

- People paying for their own care from their own savings, until such times as those savings have reduced enough to meet the threshold.

- People’s needs not being met formally, but through appropriate informal care from family members, neighbours and the charitable sector.

- People’s care needs not being fully met to an appropriate quality or, in the worst cases, not met at all, with potential negative impacts on both individuals and the NHS acute sector.

It is not clear to what extent each of these scenarios occur. The health and social care system is under immense and growing pressure, and unmet social care needs must be met elsewhere. To alleviate pressure on the rest of the health care system as much as possible, more steps need to be taken to ensure that those in need are not falling into the last category.

Wider public spending

The past decade has been the most austere in the history of the NHS, with funding growing at just 2.1% per year, less than two-thirds of the long-run average of 3.7%, and just a third of the 6.0% it averaged in the decade beforehand. But spending on health has been protected compared with other areas of public spending. As a percentage of public spending, it has grown from 17% in 2008/09 to 19%. This reflects the overall constraints on public spending. Spending on education, defence, public order and safety, and housing and community amenities all fell in real terms between 2008/09 and 2016/17.

The NHS is one of the few government departments whose budget is protected, along with aid and defence spending. Unprotected spending in other departments is set to fall in both per capita terms and as a share of GDP over the next four years.

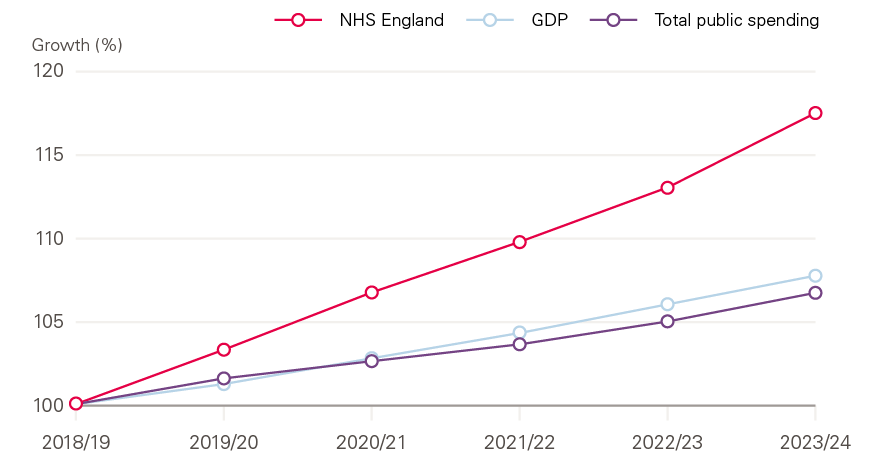

Figure 14: Real-terms growth in the NHS England budget, GDP, and total public spending

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook (2019).

NHS England’s budget, however, is due to grow much faster than either GDP or public spending. Between 2018/19 and 2023/24, NHS England’s budget will increase by 18% in real terms, more than twice as fast as the projected GDP growth of 8% and the projected total public spending growth of 7%.

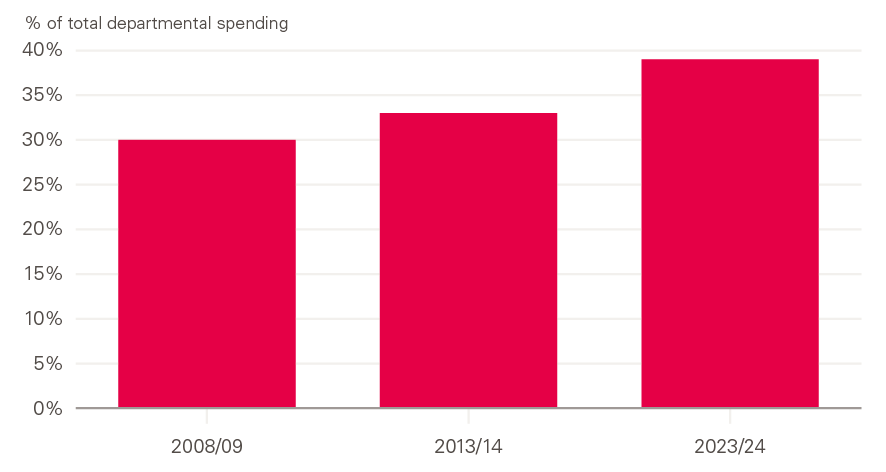

This could increase total health spending as a percentage of GDP from 7.4% to 8.1%, and as a percentage of total public spending from 19.3% to 21.3% over this period. The same trend can be seen when looking at spending by government departments, which accounts for about 40% of public spending. Health is set to account for an ever-growing share of departmental spend – 39% of total departmental spending (not including annually managed spending such as benefits) in 2023/24, up from 30% in 2008/09 and 33% in 2013/14. This is as a result of restrained spending plans in other areas, many of which also need investment.

Figure 15: Department of Health and Social Care spending as a percentage of total departmental spending

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility Economic and Fiscal Outlook (2019).

The budget for health needs to be taken in the context of wider public spending. The health of the population is not just determined by health spending but also areas like housing, education and benefits. In the long term, investing in health care at the expense of these other areas is not sustainable. The NHS has been rightly protected during the period of austerity and beyond, although spending growth remains low by historical standards. If the intention is to invest in improving people's health, spending in these areas needs to mirror the commitments made to the NHS.

** Total public spending here refers to the Office for Budget Responsibility's projections of Total Managed Expenditure (TME) as at the March 2019 Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Conclusion

The NHS long term plan sets out laudable ambitions to improve patient outcomes and shift the focus of health care towards mental health, and primary and community services. But realising this ambition will be hugely challenging. It will only be possible if it is backed by credible plans to moderate the growth in demand pressures for acute and specialist care, and if mental health, and primary and community services can access the staff they need.