Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the hospitals and research participants involved in this learning report and the research team: Professor Alison Holmes, Professor Mary Dixon-Woods, Dr Raheelah Ahmad, Dr Elizabeth Brewster, Dr Enrique Castro-Sánchez, Dr Federica Secci and Dr Walter Zingg. With input from Susan Burnett, Professor Ewan Ferlie, Tracey Galletly, Fran Husson, Claire Kilpatrick, Dr Reda Lebcir and the Patients Association.

Contact

Alison Holmes Professor of Infectious Diseases, Imperial College London alison.holmes@imperial.ac.uk

Foreword

It is with pleasure that I write the foreword for this concise learning report on infection prevention and control (IPC), which builds on the large body of work conducted by researchers at Imperial College London and the University of Leicester. The Health Foundation has brought together a strong multidisciplinary team to review activity and interventions to reduce health care associated infections (HCAI) in English acute care organisations over the last 15 years with the aim of ensuring that key learning can be collectively reflected upon and to shape further national and local activity.

Continuous learning is a key Health Foundation principle and is particularly supported by one of the overriding lessons highlighted in this report: namely, the importance of ensuring that any major interventions, such as local antimicrobial resistance (AMR) action plans, are supported by a planned analysis which should examine impact and implementation as well as cost-effectiveness. Such an understanding would form a solid basis for informing further interventions. There has been much interest internationally in some of the UK’s significant successes in HCAI reduction, but there is little material available for shared learning in the absence of adequate studies on national interventions.

The key lessons in this report are being well heeded and are being discussed with relevant partners to ensure actions are put in place to address them. These actions should build upon this learning report, recognising that whilst IPC behaviours of those working at the front line are critical, they must also be actively supported and positively reinforced by a hospital environment that supports best IPC practice and minimises risk. Several of the findings and key lessons particularly in relation to the need to address AMR are also reinforced by the Chief Medical Officer’s report UK 5-year Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Strategy (2013–2018). I am also pleased to acknowledge that the Health Foundation is becoming involved in improving antibiotic prescribing behaviours, which is a key aspect of IPC.

I am delighted that the views and input from our patients and the public have been particularly invited and explored in this report and that there will be ongoing work to better understand public and patient engagement and involvement.

Even though the scope of this commissioned report was confined to acute care and to HCAI prevention, the authors make two fundamental recommendations that should be considered by policymakers. These are, firstly, that addressing the threat of AMR must be more effectively integrated with the delivery of strong IPC and, secondly, that tackling any transmissible organism must be addressed comprehensively across the whole patient journey. Organisms do not respect boundaries between community, primary and secondary care, so a whole health care economy approach is vital.

As Chair of the Department of Health advisory committee on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare associated infection (ARHAI), I fully endorse the lessons within this learning report. I am delighted that ARHAI will discuss actions to address the report’s findings with the Health Foundation in the coming year.

Professor Mike Sharland

Chair of the Department of Health advisory committee on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare associated infection (ARHAI)

Glossary of common abbreviations

|

Abbreviation |

Definition |

|

AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance – this occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change in ways that render ineffective the medications used to cure the infections they cause. When the microorganisms become resistant to most antimicrobials they are often referred to as ‘superbugs’. This is a major concern because a resistant infection may kill, can spread to others and imposes huge costs on society. |

|

BSI |

Bloodstream infection (also known as a bacteraemia) – an invasion of the bloodstream by bacteria. This may occur through a wound or infection, or through a surgical procedure or injection. There may be no symptoms and it may resolve without treatment, or it may produce fever and other symptoms of infection. In some cases, a BSI leads to septic shock, a life-threatening condition. |

|

BBV |

Blood-borne viruses – for instance, Hepatitis B and C, and HIV, can be transmitted to health care workers or patients. |

|

CAUTI |

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection – for patients with a urinary catheter, germs can travel along the catheter and cause an infection in the bladder or kidney – CAUTIs are one of the most commonly reported HCAIs. |

|

CDI |

Clostridium difficile infection – a type of bacterial infection that can affect the digestive system. It most commonly affects people who have been treated with antibiotics. The symptoms of a C. difficile infection can range from mild to severe diarrhoea. |

|

CLABSI |

Central line-associated bloodstream infection – a serious infection that occurs when germs (usually bacteria) enter the bloodstream through the central line. A central line (also known as a central venous catheter) is a catheter (tube) that doctors often place in a large vein in the neck, chest or groin to give medication or fluids or to collect blood for medical tests. You may be familiar with intravenous catheters (also known as IVs), which are used frequently to transmit medicine or fluids into a vein near the skin’s surface (usually on the arm or hand) for short periods of time. Central lines are different from IVs because central lines access a major vein that is close to the heart. They can remain in place for weeks or months and are much more likely to cause serious infection. Central lines are commonly used in intensive care units. |

|

CRBSI |

Catheter-related bloodstream infection – a clinical definition, used when diagnosing and treating patients. It requires specific laboratory testing to more thoroughly identify the catheter as the source of the BSI. It is often problematic to precisely establish if a BSI is a CRBSI due to the clinical needs of the patient (the need to extract the catheter to be sure). |

|

CPE |

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae – a multi-resistant bacteria emerging globally, it is resistant to the last line of antibiotics. |

|

E. coli |

Escherichia coli – bacteria commonly found in the lower intestine. The most frequent cause of urinary tract infections and BSIs, it can cause food poisoning. |

|

GRE |

Glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus – bacteria which is carried harmlessly in the gut. GRE is a type of Enterococcus that is resistant to the glycopeptide type of antibiotics (eg vancomycin, teicoplanin). |

|

S. aureus |

Staphylococcus aureus – also known as staph, this is a common type of bacteria. It is often carried on the skin and inside the nostrils and throat, and can cause mild infections of the skin, such as boils and impetigo. If the bacteria get into a break in the skin, they can cause life-threatening infections, such as blood poisoning or endocarditis. |

|

HCAI |

Health care associated infections – infections that develop as a direct result of medical or surgical treatment or contact in a health care setting. |

|

MRSA |

Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus – a type of bacteria that is resistant to a number of widely used antibiotics. This means that MRSA infections can be more difficult to treat than other bacterial infections. |

|

MSSA |

Meticillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus – a type of bacteria which lives harmlessly on the skin and in the nose, in about one third of people. People who have MSSA on their bodies or in their noses are said to be colonised. MSSA colonisation usually causes no problems, but the bacteria can cause an infection when it gets the opportunity to enter the body. This is more likely to happen in people who are already unwell. MSSA can cause local infections such as abscesses or boils and it can infect any wound that has caused a break in the skin, eg grazes, surgical wounds. MSSA can cause serious infections called septicaemia (blood poisoning) where it gets into the bloodstream. However, unlike MRSA, MSSA is more sensitive to antibiotics and therefore easier to treat. |

|

SSI |

Surgical site infection – a surgical site is the incision or cut in the skin made to carry out a surgical procedure, and the tissue handled or manipulated during the procedure. A surgical site infection occurs when microorganisms get into the part of the body that has been operated on and multiply in the tissues. |

|

UTI |

Urinary tract infection – an infection of any of the following: kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra. |

|

VAP |

Ventilator-associated pneumonia – pneumonia that develops 48 hours or longer after mechanical ventilation is given by means of an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy. |

|

VRE |

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus – Enterococcus is a type of bacteria that everyone has in their bowel. Vancomycin is one of the antibiotics (a glycopeptide, see GRE above) used to treat infections caused by the Enterococcus germ. Sometimes this germ develops resistance to vancomycin. When this occurs, the infection can no longer be treated by vancomycin. |

Introduction

Infection control has been high on the political agenda and on the agenda of the NHS in England for the last 15 years. During this time there have been many successes, not least the reduction in MRSA bloodstream infections (BSIs) and cases of Clostridium difficile infection. Though these successes should be celebrated, it is important not to become complacent. Other health care associated infections (HCAIs) that have not been monitored as rigorously are growing in incidence. New infections, including the growing number of more resistant strains of bacteria, are in danger of spreading. As a result, infection control needs to remain central to the work of the NHS and it is essential to continue building on the achievements of recent years to reduce mortality, morbidity and health care costs.

This report considers what has been learned from the infection prevention and control (IPC) work carried out over the last 15 years in hospitals in England and looks at how these lessons should be applied in future. Should the NHS continue to respond in the same way to infection threats or should new approaches be adopted? Of all the interventions made during this period, what has worked best? Is it even possible to tell? How have all the infection control procedures and practices impacted on the front line in clinical care and on service users?

The lessons the report sets out are drawn from the findings of a large research study that identified and consolidated published evidence from the UK about national IPC initiatives and interventions and synthesised this with findings from qualitative case studies in two large NHS hospitals, including the perspectives of service users recorded during consultation events.

The report begins with an overview of HCAIs, especially those linked to hospitals. With this background, the landscape of infection control in English hospitals is set out, including recent successes and the challenges ahead. The report goes on to draw out lessons to help inform future work to maintain hospitals as safe places.

What are health care associated infections?

Health care associated infections are infections that develop as a direct result of medical or surgical treatment or contact in a health care setting., They can occur in hospitals and in health or social care settings in the community and can affect both patients and health care workers. An infection occurs when a germ (an organism such as a bacterium, virus or fungus) enters the body and attacks or causes damage to it. Every individual is covered with bacteria on their body and also carries trillions of them in their gut. Any medical or surgical procedure that breaks the skin or any mucous membrane, introduces any foreign material or reduces immunity creates a risk of infection. Some infections can enter the bloodstream and become generalised throughout the body. This is known as a bacteraemia or bloodstream infection (BSI).

In this report we focus particularly on those infections that arise during hospital care. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) BSIs and C. difficile associated diarrhoea (C. difficile infection) are two well-known HCAIs that have been the focus of attention in England, but there are many more. MRSA BSIs are particularly associated with intravenous devices (eg central lines) and C. difficile with antibiotic exposure. Hand hygiene, environmental hygiene, the capacity to isolate patients and assuring optimal antibiotic prescribing are all critical aspects of prevention of both.

Other HCAIs include BSIs caused by other organisms, urinary tract infections related to urinary catheters (CAUTIs), respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia related to being ventilated (VAP), or wound or surgical site infections (SSIs). Microorganisms come from droplets that are sneezed or coughed (eg flu), from air (eg tuberculosis), or from water (eg legionnaires’ disease); they are passed within the hospital or they can come in from the community (eg norovirus). Germs causing HCAIs may have different modes of transmission and different sources, and patients may have different profiles of risk factors making them more vulnerable to an HCAI, but some core infection prevention principles remain the same.

In hospital, infections can generally be classified as either transmission-dependent or as arising from a patient’s own microbial flora (endogenous transmission). Transmission-dependent infections involve the acquisition of the pathogen from the health care environment, for example person-to-person (for instance, through inadequate hand hygiene) or from contaminated equipment, devices and environments (exogenous transmission). Infections from a patient’s own microbial flora may arise post-surgically or post-insertion of invasive devices such as intravenous lines. Prevention here relies on skin cleansing and, for some procedures, prophylactic antibiotics.,,

The landscape of infection control in England since 2000

A 2000 National Audit Office (NAO) report was highly critical of the strategic management of HCAIs in England. Suggesting that infection control was the Cinderella of the health service, the report criticised the lack of information about the infections and the limited resources allocated to infection control teams. A key problem was that the size and scope of HCAIs was simply unknown. A voluntary scheme for reporting BSIs had existed during the 1990s, but suffered from problems of completeness and comparability. More broadly, the report suggested that HCAIs had come to be seen as an intractable problem, regarded by those working in hospitals (clinicians and managers) as an inevitable consequence of providing health care. Such infections were thus regrettable, but were to a large extent tolerated.

In 2001, mandatory reporting of MRSA BSI cases in hospitals was introduced, with a few other selected infections included in the surveillance programme in subsequent years. Further national reports in 2003 and 2004 suggested some improvement, including evidence of hospital trusts giving higher priority to infection control., But criticism remained of the failure of the NHS to ‘get a grip’ on both the extent and the cost of HCAIs.

At the same time, HCAIs became a frequent and often vivid topic in the media, and a focus of huge public concern and political attention. Three recurring themes were evident: the vulnerability to infection and corresponding fear felt by patients; dirty wards, which, it was claimed, often occurred when cleaning contracts were outsourced and the standards of cleaning dropped; and a demand to ‘bring back matron’, seen as the solution to nurses’ poor compliance with prevention measures. Analysis of newspaper reporting at the time shows a steady increase in stories of ‘hospital superbugs’, peaking in the run-up to the 2005 election, when hospital hygiene became a highly publicised issue. A separate analysis of reporting about MRSA in 12 newspapers between 1994 and 2005 identified that the momentum was fuelled in part by celebrity stories and some fictional media. Interestingly, the role of the pressure of antibiotic use in driving this increase was rarely discussed. By 2008, a BBC poll was reporting that the risk of acquiring an infection was the main fear of the public about inpatient care.

The combination of critical reports and media publicity produced important agenda-setting effects, converting HCAI from a problem that had become rather neglected and under-resourced into a social problem, demanding a solution in the face of intense public and political pressure. High-profile policy interventions followed in close succession.

Progress and successes, 2000 to 2015

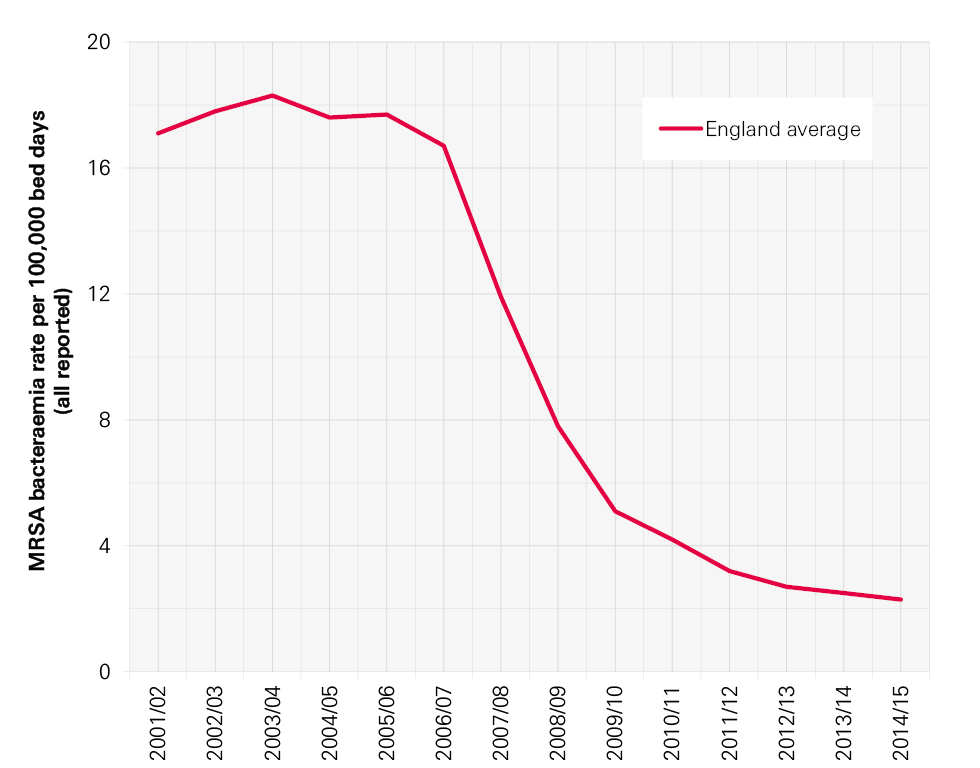

The mandatory surveillance of MRSA BSI cases was introduced in April 2001. It was managed by the Health Protection Agency (HPA) on behalf of the Department of Health. A new target was introduced to NHS acute trusts in April 2005: the year-on-year reduction of MRSA BSI rates. The data show striking progress towards this target, with MRSA bloodstream infection rates (expressed as cases per 100,000 bed days) in steady decline in England since 2004 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Annual rates of MRSA BSIs for NHS trusts in England per 100,000 bed days, 2001/02–2014/15,

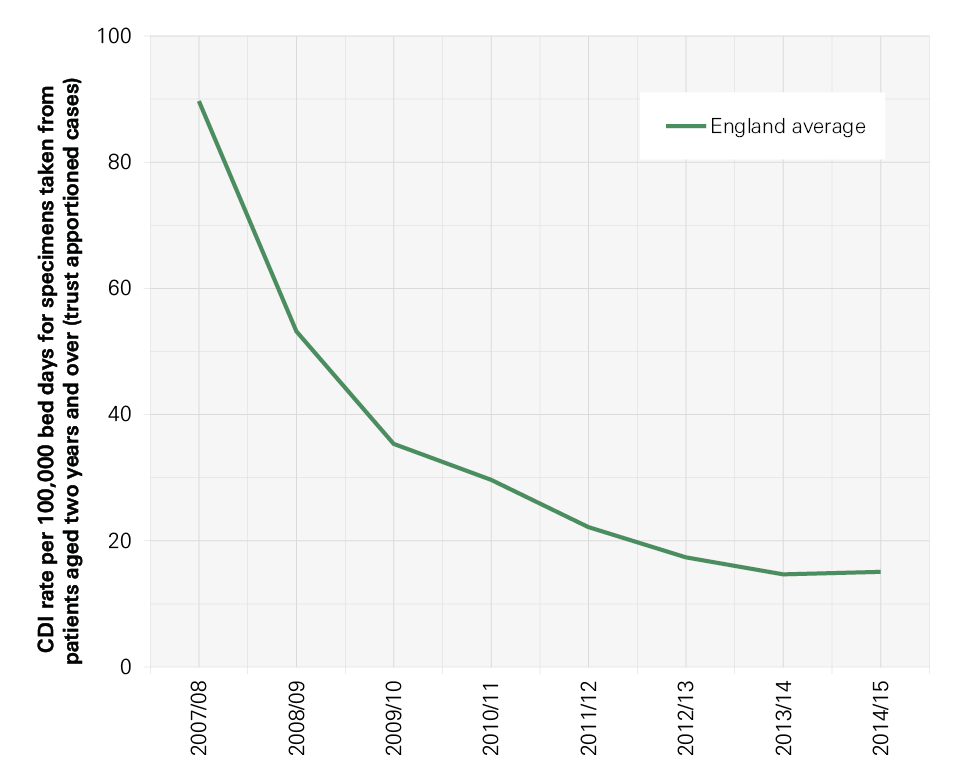

Mandatory surveillance was extended to glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcal (GRE) BSI in October 2003, C. difficile infection (CDI) for people aged over 65 in January 2004, meticillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) BSI in January 2011 and Escherichia coli (E. coli) BSI in June 2011. The reporting of CDI was extended to everyone over the age of two in 2007 after the inquiry into the C. difficile outbreaks at Stoke Mandeville (where the focus on MRSA alone was cited as a contributory factor to the CDI outbreak). Trust apportioned rates show a decline since 2007/08 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Annual C. difficile rates in England, 2007/08–2014/15,

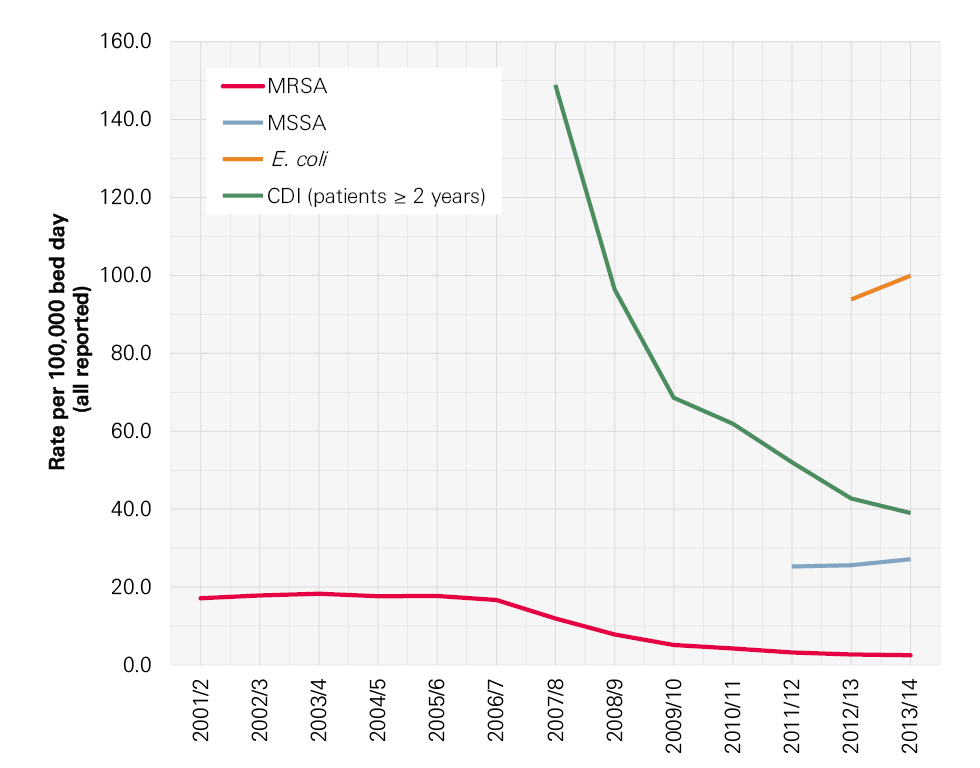

Not all progress has been in the right direction, however. E. coli represents the most rapidly increasing and most common BSI, accounting for 36% of the BSIs seen nationally, compared with 1.6% caused by MRSA (see Figure 3, overleaf).23

Figure 3: All reported rates England average: MRSA BSI, C. difficile infection, MSSA BSI, E. coli BSI, 2001/02–2013/14,,,,,

Health care associated infections in 2015 and challenges ahead

The most recent studies report that between 5.1% and 11.6% of hospitalised patients will acquire at least one HCAI, with the risk of HCAI greatest in intensive care units (ICUs), where the prevalence is 23.4% (with a 95% confidence interval of 17.3–31.8)., The best estimates available for attributable deaths from HCAI are those attributable to Staphylococcus aureus BSI or C. difficile infections. These combined estimates have been recorded as causing 9,000 deaths per year.,

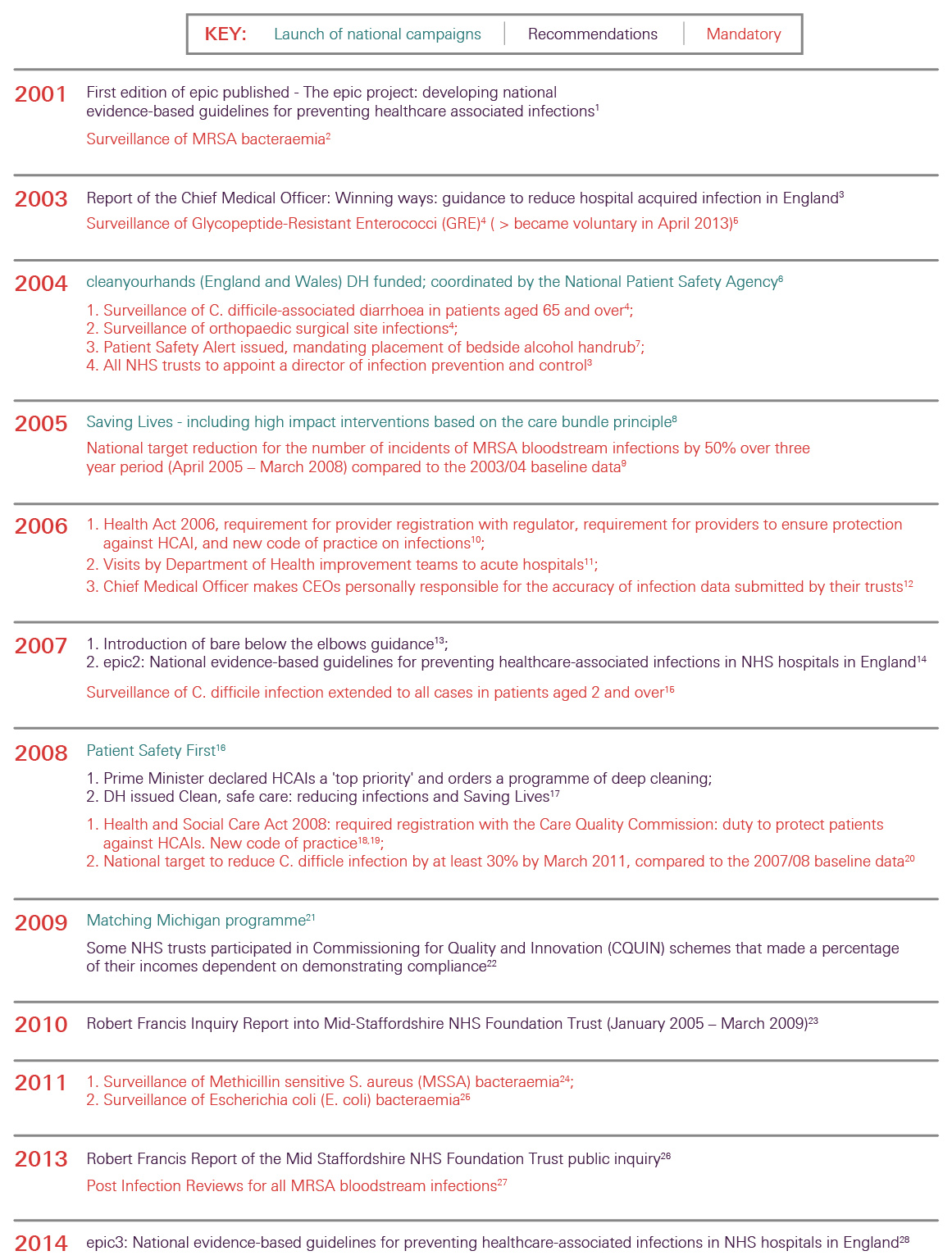

Figure 5: Timeline of selected interventions to reduce HCAIs and improve IPC

For details of the references in this timeline, see www.health.org.uk/hcai

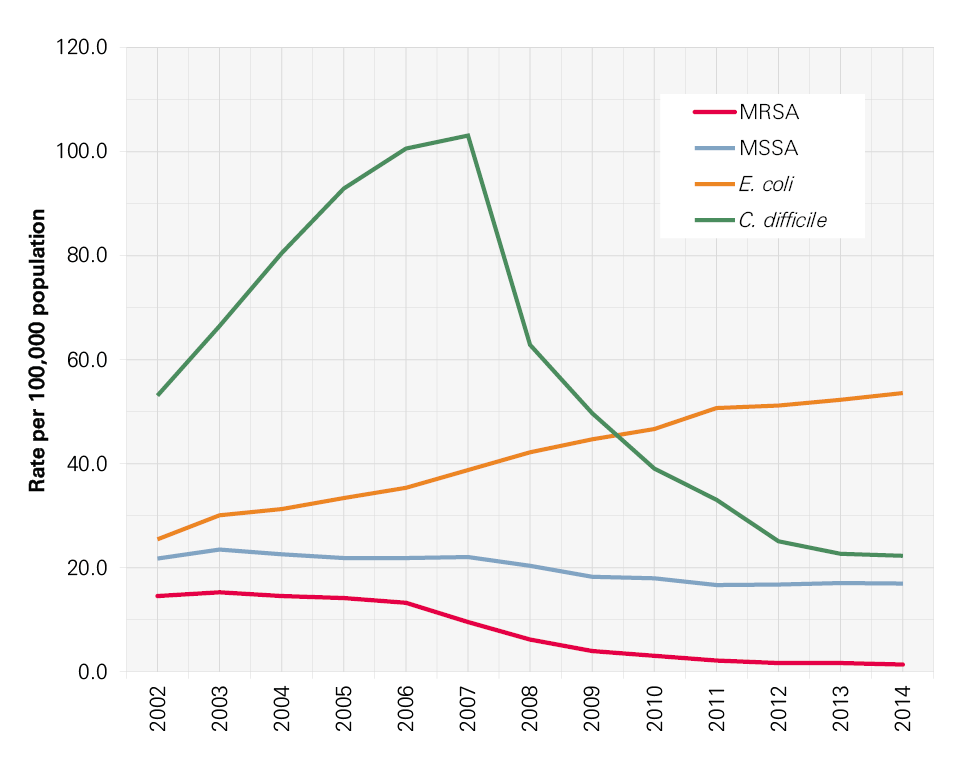

The types of infections occurring have also shifted, with far fewer MRSA bloodstream and C. difficile infections, but increasing numbers of BSIs caused by E. coli and other bacteria increasingly resistant to the effects of antibiotics or the actions of the body’s immune system.

Figure 4 shows the trends in infections in the population as a whole rather than in people in hospital. This shows how infections in hospital mirror those in the wider community. For example, the spike in C. difficile in the financial year 2006/07 and the current rise in E. coli BSIs are being experienced in the population as a whole, and, inevitably, in hospitals too.

Figure 4: Trends in C. difficile infection, MRSA, MSSA and E. coli BSIs (England 2002–2014, calendar years)

In her annual report in 2011, the Chief Medical Officer set out the challenges ahead for infections in the UK and in particular for the joint challenges of antibiotic resistance, infection prevention and HCAI:

- The host: as medicine becomes more successful in keeping us alive, more and more people in the population are immunocompromised. This includes the increase in the numbers of older people; more babies (neonates) surviving pre-term; more people with lifestyle risks (obesity, smoking, excess alcohol consumption); and more people on immunosuppressant drugs for conditions such as cancer and renal transplant.

- The environment: as hospitals get busier, the ease with which infections can spread increases. The risk may be increased by overcrowding; poor cleaning due to areas being too busy; inadequate facilities for hand hygiene and poor aseptic technique.

- The pathogens: many more pathogens are becoming resistant to antibiotics and new pathogens are now coming into hospitals.

To truly address infection prevention and antimicrobial resistance (AMR), action must not be confined within the walls of a hospital; it must consider all aspects of patient care and pathways. That includes community, primary and hospital care and includes the health care professionals and patients within and across each of these settings – ie across the whole health care economy.

Lessons from research about acute care in England

Many lessons can be learned from the tremendous amount of work undertaken in England over the last 15 years to improve infection prevention and control (IPC). In this section, we set out a brief summary of findings and conclusions from our research. Our research methods are set out in more detail in Appendix 1.

Briefly, we used a mixed-method approach incorporating literature reviews, qualitative case studies including interviews with members of staff from ward to board in two acute hospitals in England, and a user consultation event to hear the views of patients and the public. We also undertook a scoping exercise to identify the availability and use of data to monitor HCAI and indicators of IPC performance in UK hospital trusts. Data from three previous studies were used: one, the Lining Up ethnographic study of intensive care units’ attempts to reduce central venous catheter bloodstream infections, and two large-scale innovation adoption studies (Commissioned by the Department of Health; and funded by the National Institute for Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research).

Evaluating campaigns and initiatives for infection prevention and control

The timeline set out in Figure 5 shows the concentration of interventions targeting HCAI in hospitals since 2000. These range from mandatory reporting of selected infections, regulatory interventions, national guidelines and national campaigns that were often running in parallel. Perhaps the most influential intervention was the early introduction of mandatory surveillance of MRSA BSIs. This quantified the problem and made it clear that action was needed across the NHS. Following on from this, in 2004 the national cleanyourhands campaign was launched. Among many changes introduced in this campaign, the most visible are the alcohol hand-rub dispensers that can be seen throughout hospitals. Further initiatives have been based on the use of ‘care bundles’, which group together practices that should be performed consistently. Programmes that used bundles included Saving Lives High Impact Interventions, Patient Safety First and Matching Michigan. These initiatives were aimed at improving reliability in the use of procedures known to prevent surgical site infections, central venous catheter infections and infections linked to ventilators in intensive care units.

HCAI rates have declined over this period, but our research showed that it is impossible to attribute success to any one initiative, nor is it possible to say which components of any one programme were critical. We do know that multimodal interventions work. We also know that having the backing of a national campaign gains the attention of trust executives, bringing focus and resource to IPC where needed and providing strong external reinforcement.,, But much learning about what works in large-scale IPC programmes has been lost because so little research and evaluation was conducted to determine effectiveness or to identify mechanisms of change and contextual influences. A key lesson here is that future campaigns would benefit from a programme of evaluation running in parallel to help understand what works and why. Also important for future campaigns will be a requirement for a systems-wide focus across entire health economies, rather than confining efforts and resources to the acute sector.

Figure 5: Timeline of selected interventions to reduce HCAIs and improve IPC

For details of the references in this timeline, see www.health.org.uk/hcai

The effective organisation of infection prevention and control at trust level

In our research, it was clear that organisations may aspire to best practice in IPC. Executive team members in our case study hospitals commented that IPC was on the agenda for every board meeting and was integrated into trust strategy. IPC interventions were ‘very visible’. Many of those working on the front line felt that IPC was a high priority in the area in which they worked and that colleagues generally understood what good IPC involved.

Despite the high priority given to IPC, often it was not considered part of wider patient safety and quality improvement work in hospitals. This has meant that at the front line, IPC work may be seen as competing with other patient safety and quality strategies. Trusts need to be aware of this, and where possible bring the improvement work together in an integrated way at the clinical front line while maintaining the necessary expert input.

A key lesson is that trusts must continue to have both the structural and cultural capacity to deliver effective IPC. They should recognise and understand the impact of a positive organisational culture since it has implications for staff turnover and motivation and is important when looking at the sustainability of approaches to IPC.

Leadership

Participants in our research stressed the need for strong leadership to support activities to prevent and control infection within the organisation. They also emphasised the need for support for IPC to be fully aligned, from the trust board, executive team and specialist infection control staff through to all those working on the front line (both clinical and non-clinical). Two views were expressed on leadership: one stressed the need for leadership and support from specialist infection control staff; the other emphasised the need for clinicians working on the front line to ‘own’ and lead themselves.

Since 2004, all NHS trusts have been required to have a director of infection prevention and control (DIPC) to provide a direct line of accountability to the CEO and the board. The DIPC is intended to lead and champion IPC at multiple levels within the organisation, ensuring that a consistent messages and best practice are embedded and continuously improved in directorates, groups, teams and networks. Many other clinical and managerial roles in hospitals now have IPC built into their responsibilities, including matrons, clinical directors, directorate managers, ward managers, pharmacists and others.

A key lesson here is that leadership for IPC needs to be distributed throughout an organisation, with clinical champions identified in all areas.,, This is especially important as we found that, at the sharp end of care, health care workers had to address competition between immediate priorities and best IPC practice on a day-to-day basis.

The role of measurement and monitoring in infection prevention and control

Our research found that there can be little doubt about the value of mandatory surveillance systems for specific infections. Surveillance, involving the measurement and reporting of infections according to agreed definitions and with timely feedback, makes problems visible and hence actionable. Surveillance is now part of day-to-day life in clinical areas. For organisations, data on their particular infection rates and their own problems are critical in stimulating action, particularly when teams can identify that they are performing poorly in comparison with similar trusts.

The available data suggest that some infections (such as MRSA bloodstream infections) have shown a welcome reduction, but at the same time others have risen in number. Since these latter infections are not in the national spotlight, their rise has almost gone unnoticed, particularly at the hospital level. Care needs to be taken to ensure that all locally relevant HCAIs are monitored in hospitals, not just those subject to mandatory surveillance. At the national level, measures also need to be appropriate and able to change in response to the shifting epidemiology of infectious diseases.

We also know now that at the trust level, understanding IPC needs a wider set of data. Recent research has identified that a suite of organisational process and outcome indicators need to be assessed in order to monitor IPC performance (Table 1). These indicators cover such issues as the effective organisation of IPC at a hospital level; measures of how crowded or busy a hospital is from data on bed occupancy and staffing levels; how many temporary members of staff are employed; levels and take-up of education and training in IPC; the findings from regular audits against agreed guidelines; and – recognising the role of a positive organisational culture in good IPC – some regular measures of safety culture.

Table 1: Recommended organisational components for effective Infection prevention and control

- Effective organisation of IPC at a hospital level.

- Effective bed occupancy, appropriate staffing and workload, minimal use of pool/ agency nurses.

- Sufficient availability of and easy access to materials and equipment, optimisation of ergonomics.

- Use of guidelines in combination with practical education and training.

- Education and training (involves front-line staff and is team- and task-oriented).

- Organising audits as a standardised and systematic review of practice with timely feedback.

- Participating in prospective surveillance and offering active feedback, preferably as part of a network.

- Implementing IPC programmes following a multimodal strategy, including tools such as bundles and checklists developed by multidisciplinary teams, and taking into account local conditions (and principles of behavioural change).

- Identifying and engaging champions in the promotion of intervention strategies.

- Promoting positive organisational culture by fostering working relationships and communication across units and staff groups.

Regulation

IPC is now embedded in the regulatory structures governing NHS care in England, with oversight by the Care Quality Commission. It was clear in our research that this external regulatory pressure has been felt at all levels in NHS organisations and is seen by many in the case study organisations as having stimulated action that has improved care for patients. The external emphasis on HCAI was reported to have brought about a new shared acceptance of the importance of IPC and the need for it to be a collective responsibility. Given the figures for infection in the wider population (see section 1), in the context of the restructured NHS in England, this shared ownership now needs to extend beyond the hospital setting to primary care and the clinical commissioning groups.

Regulation has been important in keeping IPC central to the NHS agenda, particularly for trust boards. However, too narrow a focus or too harsh a regime can have unintended consequences, including the neglect of other important infections; for this reason, future inspection and regulation needs to be designed well, for example, taking into account specific local infection risks that are relevant for that trust.

Keeping patients and the public informed

The national media has continued to take an interest in infection prevention and in infections more generally. The influence of the media on patient perceptions has been reported in many research papers. In our interviews, members of staff discussed both the positive and negative impacts of the media on IPC practices in their hospital. Some felt that media coverage of infections and outbreaks was unhelpful, but some also reported that the raised profile of IPC helped to drive up standards. Our research found that patients took a more holistic view of safety in hospitals than just MRSA rates when able to access this information.

Care bundles

A key principle underpinning the government’s strategy on HCAIs is that clinical procedures performed on patients should be done correctly and with appropriate infection control on every occasion. The care bundle approach, which involves assembling evidence-based or logical actions into a group of tasks that should all be performed consistently for specific activities, has been seen as key to this and has been widely adopted.

Research has shown that using care bundles has benefits when used as part of a wider multimodal improvement programme involving all aspects of what has been shown to work.

In our research hospitals, participants appreciated the clarity about expected practices that care bundles bring, but only if the practices are evidence-based and continue to be updated as new knowledge is discovered.

Screening and vaccination strategies

Research suggests that universal admission screening for MRSA is associated with decreased colonisation, MRSA BSI and mortality. These studies indicate that effective infection prevention approaches need to consider the entire health care economy in order to be effective and sustainable. Comprehensive strategies to reduce carriage and the clinical reservoir of MRSA are required if progress towards zero preventable BSIs for all MRSA BSIs is to be achieved.

Screening on or prior to admission is beneficial but can require a lot of resources. If screening is to be carried out routinely for organisms of particular concern, then it is crucial that effective structures are introduced within the organisation to minimise the impact on nurses and infection control practitioners., In parallel, the isolation capacity of the hospital must be considered and managed, as the screening will increase the isolation demand. This is becoming a particularly pertinent issue for acute trusts, as the NHS is expected to deliver on the Public Health England toolkit for the management and control of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE), a multi-resistant bacteria of significant global concern.

Vaccination is important for IPC, both for patients and people working in health care. It prevents important infections such as measles, which can be very dangerous to some vulnerable patients. Hepatitis B vaccination can protect people working in health care from acquiring the virus from patients they care for and flu vaccination reduces staff sickness and resulting ward staffing absences during flu outbreaks. Vaccination also plays an important role in reducing antibiotic usage.

The future of infection prevention and control

Drawing on what the research found about the successes and challenges in infection prevention and control (IPC) over the last 15 years, we now move on to look at the lessons learned and offer examples for future directions for effective IPC.

Measures for infection prevention and control need to be appropriate and responsive.

Surveillance has allowed us to understand the extent of the problem of infection in hospitals and has provided motivation to trust boards and clinical teams to engage in IPC. In future, measures of progress need to be appropriate and responsive over time, taking into account new infection threats in hospitals and where infection threats have reduced significantly.

For example:

- National mandatory surveillance must continue for specific infections, but must take into account and respond to new and emerging infection threats.

- Care needs to be taken to ensure that local surveillance is appropriate and all relevant HCAIs are monitored in hospitals, not just those subject to mandatory surveillance, which can skew efforts away from infections that are on the rise or those of local importance. All health care associated BSIs relevant to the local trust should be monitored (for example in neonatal, paediatric or adult ICUs, in haematology or in haemodialysis), and the local surveillance of surgical site infections should reflect the surgery performed at the trust, not just the mandatory surveillance of orthopaedic joint replacement surgery.

Infection prevention and control should remain central to inspection and regulation.

Future inspection and regulation needs to be well designed. It should consider the local infection profile and the local vulnerable patient groups, specialities or risk procedures of a trust and its community, and also include antibiotic stewardship. It must also consider managerial responses to minimising risk so that unintended consequences can be anticipated.

For example:

- Strong management support for IPC, including surveillance support, maximising environmental hygiene and isolation capacity should be tangible and clearly evident.

- Antibiotic stewardship activities should be included in any IPC review.

- Local IPC programmes must address HCAI risks of local patient population, specialities and procedures.

All national-level campaigns require an explicit framework underpinning how the campaign is intended to work and must be accompanied by an evaluation strategy.

National campaigns have had an impact across the NHS, but it is impossible to say for certain what component has worked or which aspects have been particularly important in reducing infections in hospitals. It is important that future campaigns are evaluated in order to learn and to be confident in what works and why.

For example:

- Future campaigns must address the basics of what is already known to work for IPC.

- Future campaigns must involve the whole health economy.

- All future campaigns must only be launched when there is an evaluation strategy in place.

Hospitals must have the structural and cultural capacity to deliver effective infection prevention and control and antibiotic usage.

Effective IPC requires the underpinning of a healthy organisation with the capacity and capability to learn and to improve on a range of fronts (see Table 1: Recommended organisational components for effective infection prevention and control). There should be a move to introduce indicators of a healthy organisation and these must be linked to the outcomes of IPC.

For example:

- A range of process and outcome measures should be used to monitor effective IPC.

- A positive organisational culture should be fostered to ensure IPC is maintained. More work is needed at the trust level to measure and understand this.

Trusts need to ensure that the goals for infection prevention and control and patient safety are integrated and aligned at the clinical front line.

We found that at times those working at the front line were overwhelmed with the requirements for IPC, patient safety and quality improvement initiatives. This can demotivate the exact people who need to remain engaged in IPC. Clearly the goals for IPC and patient safety need to be integrated and aligned so that ‘doing the right thing, in the safest possible way’ is the easiest thing for people to do.

For example:

- Trust boards should integrate and align goals for IPC, safety and quality so that ‘doing the right thing’ is clear to all.

Clinical and managerial leaders of infection prevention and control are needed at all levels in the organisation.

The challenges ahead for IPC mean that it must remain central to the NHS agenda and the work in all health care organisations. As such, clinical and managerial leaders of IPC are needed at all levels with demonstrable managerial and clinical commitment. This must also be supported by champions of good practice who lead by example.

For example:

- Leaders of IPC should be identified at all levels in a trust and supported appropriately.

- Champions of IPC who lead by example are needed.

Define the role of the public before they become patients.

In the context of often high media coverage, health care organisations need to understand better how the public and patients make sense of publicly available indicators and information. IPC education, awareness of hand hygiene and the optimal use of antibiotics need to be instilled in the wider public before they become patients, since studies have suggested that patients are less likely to get involved at the point of care.

For example:

- Patient education needs to start with the wider public understanding and using meaningful indicators and supporting campaigns.

- People working in hospitals should also be able to discuss what infection indicators mean with patients.

A whole health economy approach is needed for infection prevention and control in future.

Bugs don’t differentiate between primary and secondary care or between hospital and home, yet most of the IPC focus to date has been on the hospital. It is time now to move to a whole health economy approach. This will require measures of HCAI that span health sector boundaries and look at the whole patient pathway. Economic analysis using a public health approach in the wider community is needed to fully understand the impact of HCAIs and to enable interventions to be developed that will have most impact for their investment.

For example:

- The future focus of IPC should be across the whole health economy, promoting joined up working.

- Measures of HCAI prevention activity and antibiotic stewardship should be developed that span health sector boundaries.

- Economic analysis of IPC needs to have a system-level approach in order to understand the full impact of HCAIs and to target interventions.

Conclusion

In this report we have set out the findings from our research study and have drawn out the lessons for the future of infection prevention and control (IPC). Tremendous progress in IPC has been made in hospitals since 2000, but there are many areas that still need to be understood better. For example, how to improve screening strategies and how to design and implement patient pathways that minimise infection transmission risk in hospitals. A new approach to research in IPC is needed, with analysis aiming to explicitly consider multimodal factors. Importantly, we must learn from other countries – not just about what works in IPC, but also what doesn’t.

The central message is that we cannot take our eye off the IPC ball. Many challenges lie ahead, and IPC must remain central to clinical care and to the priorities of the NHS. Many of the successes to date have been hard won and if the focus on IPC was reduced in any way, it would not be long before the numbers would rise again. Furthermore, while attention has been focused on MRSA BSI and CDI, the numbers of other infections, such as those caused by increasingly resistant bacteria and E. coli, have been rising. Therefore, effective antibiotic stewardship activity needs to be part of any IPC programme. It is vital to continuously monitor and be alert, responsive and adaptive to all infections in hospitals, and across all health and social care settings and the community, while retaining best practice in IPC.

Appendix 1: Research methods

This report is based on a mixed-method study comprising reviews of the literature, qualitative case studies and a user consultation event. An integrated deductive-inductive approach to analysis was used. A multi-stakeholder advisory board provided guidance throughout the study process. Members included: patients’ representatives, health care practitioners and experts in IPC, health systems, psychology, sociology and organisational analysis.

The literature review was designed to examine peer-reviewed UK literature aimed at reducing HCAIs and improving health care workers’ practices relating to IPC in hospitals, during the period between January 2000 and January 2013. It focused on practices of IPC, and therefore excluded consideration of antibiotic stewardship and studies that were primarily basic science, microbiological or epidemiological in character, with no implications for practice. An extensive search of databases using specially designed search strategies was conducted. All types of study design were included. These searches identified 343 candidate articles which were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and quality assessed, resulting in 47 articles available for analysis. A scoping review of the international peer-reviewed and grey literature provided the range of indicators recommended to assess IPC performance. This informed a scoping exercise to identify the availability and use of data to monitor HCAI and of indicators of IPC performance in UK hospital trusts.

The case studies included two purposively sampled NHS trusts, one in the north and one in the south of England. The two trusts provided different contexts: a teaching hospital NHS trust and a university hospital foundation trust. Interviews with 41 members of staff were conducted in the two hospitals, with the aim of understanding the views and experiences of those with responsibility for IPC from front-line staff to executive roles. The qualitative analysis followed an integrated approach where a ‘start-up’ list of themes from the reviewed literature was used followed by an inductive exploration of the data.50 The analysis also drew on data from previous research conducted by the project team, specifically the Lining Up study (Health Foundation), and two large-scale innovation adoption studies (Department of Health, and Health Services and Delivery Research). This previous research sample included the two case study sites sampled here, allowing for a longitudinal perspective.

User views were sought through a public consultation event facilitated by the research team in collaboration with Opinion Leader and the Patients Association. A sample of 15 carers and 26 patients was recruited from across London. Recruitment was by quota sampling on ethnicity, and satisfaction level with care received by self or in capacity as a carer. Data collection was via group interviews, self-completion questionnaires and notes from direct observation. Group discussions were audio recorded, transcribed and analysed by the research team and the patient representative on the steering group (who also attended the event as an observer).

For more information, including details of all the papers included in the literature review, see www.health.org.uk/hcai

References

- Department of Health. What is a healthcare associated infection? Department of Health, 2012. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120118164404/http://hcai.dh.gov.uk/reducinghcais/hcai/ (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control 1988;16(3):128–140.2.

- Emori TG, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Sartor C, Stroud LA, Gaunt EE, et al. Accuracy of reporting nosocomial infections in intensive-care-unit patients to the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System: a pilot study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19(5):308–316.3.

- Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Greene L, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2014;35(06);605–627.

- Otter JA, Yezli S, French GL. The role played by contaminated surfaces in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(7):687–699.

- Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General – HC 230 session 1999–2000. The management and control of hospital acquired infection in acute NHS Trusts in England. London: The Stationery Office, 2000. Available from: www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2000/02/9900230.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Department of Health. Winning ways: working together to reduce healthcare associated infection in England. London: Department of Health, 2003. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4064689.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Department of Health. Towards cleaner hospitals and lower rates of infection: a summary of action. London: Department of Health, 2004. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4085861.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Taylor K. Improving patient care by reducing the risk of hospital acquired infection: a progress report by the National Audit Office. Br J Infect Control. 2004;5(5):4-5.

- BBC News. MRSA target ‘likely to be missed’. 11 July 2007. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/6249149.stm (accessed 29.09.2015).

- MailOnline. MRSA – It’s even worse than you think. 15 January 2007. Available from: www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-429027/MRSA--Its-worse-think.html#ixzz3nDGg7lXE (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Templeton, S-K, Leonard S. Health secretary Reid admits ward bug killed his mother. The Sunday Times. London: Timesonline. 17 April 2005. Available from: www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/article88938.ece (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Washer P, Joffe H. The ‘hospital superbug’: social representations of MRSA. Soc Sci Med. 63(8):2141-2152.

- Boyce T, Murray E, Holmes A. What are the drivers of the UK media coverage of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, the inter-relationships and relative influences? J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(4):400-407. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.05.022

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

- Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: developing an ex-post theory of a quality improvement program. Milbank Q. 2011;89(2):167-205.

- Public Health England (formerly Health Protection Agency). Results from the mandatory surveillance of MRSA bacteraemia. Public Health England, 2014. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714084352/http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1233906819629 (accessed 29.09.2015)

- Public Health England. Statistics – MRSA bacteraemia: annual data. Gov.uk, 2015. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/mrsa-bacteraemia-annual-data (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Chief Medical Officer, Deputy NHS Chief Executive. Extension of mandatory surveillance to E. coli bloodstream Infections – June 2011. London: Department of Health, 2011. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714084352/https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215619/dh_126221.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Healthcare Commission. Investigation into outbreaks of Clostridium difficile at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Buckinghamshire Hospitals NHS Trust. London: Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, 2006. Available from: www.buckinghamshirehospitals.nhs.uk/healthcarecommision/HCC-Investigation-into-the-Outbreak-of-Clostridium-Difficile.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Public Health England (formerly Health Protection Agency). Results from the mandatory Clostridium difficile reporting scheme. Public Health England, 2014. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714084352/http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1195733750761 (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Public Health England. Statistics – Clostridium difficile infection: annual data. Gov.uk, 2015. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/clostridium-difficile-infection-annual-data (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Davies SC. Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer, Volume Two, 2011, Infections and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. London: Department of Health, 2013. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138331/CMO_Annual_Report_Volume_2_2011.pdf

- Public Health England. Statistics – MSSA bacteraemia: annual data. Gov.uk, 2015. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/mssa-bacteraemia-annual-data (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Public Health England. Statistics – Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteraemia: annual data. Gov.uk, 2015. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/escherichia-coli-e-coli-bacteraemia-annual-data (accessed 29.09.2015)

- World Health Organization. The burden of health care-associated infection worldwide: a summary. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. Available from: www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/summary_20100430_en.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Health Protection Agency. English national point prevalence survey on healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2011: preliminary data. London: Health Protection Agency, 2012. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/331871/English_National_Point_Prevalence_Survey_on_Healthcare_associated_Infections_and_Antimicrobial_Use_2011.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General – HC 560 session 2008–2009. Reducing healthcare associated infection in hospitals in England. London: The Stationery Office, 2009. Available from: www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/0809560.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Dixon-Woods M, Leslie M, Tarrant C, Bion J. Lining up: how is harm measured? London: Health Foundation, 2013. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/LiningUpHowIsHarmMeasured.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Kyratsis Y, Ahmad R, Holmes A. Technology adoption and implementation in organisations: comparative case studies of 12 English NHS trusts. BMJ Open. 2012;2: e000872. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000872.

- Kyratsis Y, Ahmad R, Hatzaras K, Iwami M, Holmes A. Making sense of evidence in management decisions: the role of research-based knowledge on innovation adoption and implementation in healthcare. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2(6). doi: 10.3310/hsdr02060.

- Patient Safety First. About Patient Safety First. Available from: www.patientsafetyfirst.nhs.uk/Content.aspx?path=/About-the-campaign/ (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Stone SP, Fuller C, Savage J, Cookson B, Hayward A, Cooper B, et al. Evaluation of the national Cleanyourhands campaign to reduce Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and Clostridium difficile infection in hospitals in England and Wales by improved hand hygiene: four year, prospective, ecological, interrupted time series study. BMJ. 2012;344: e3005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e3005.

- Benning A, Dixon-Woods M, Nwulu U, Ghaleb M, Dawson J, Barber N, et al. Multiple component patient safety intervention in English hospitals: controlled evaluation of second phase. BMJ. 2011;342:d199. doi:10.1136/bmj.d199.

- Curran E, Harper P, Loveday H, Gilmour H, Jones S, Benneyan J, et al. Results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of statistical process control charts and structured diagnostic tools to reduce ward-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the CHART Project. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2008.06.013.

- Koteyko N, Carter R. Discourse of ‘transformational leadership’ in infection control. Health. 2008;12(4):479-499. doi:10.1177/1363459308094421.

- Ahmad R, Brewster L, Castro-Sanchez E, Dixon-Woods M, Holmes A, Zingg W. Leading for sustained change in infection control – do we need external censure or distributed leadership? Health Services Research Network (HSRN) conference – Poster presentation. Nottingham, June 2014.

- Hendy J, Barlow J. The role of the organizational champion in achieving health system change. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(3):348-355. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.009.

- Septimus E, Weinstein RA, Perl TM, Goldmann DA, Yokoe DS. Approaches for preventing healthcare-associated infections: go long or go wide? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014; 35(7):797–801.

- Zingg W, Holmes A, Dettenkofer M, Goetting T, Secci F, Clack L, et al. Hospital organisation, management, and structure for prevention of health-care-associated infection: a systematic review and expert consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(2):212–224.

- Ahmad R, Iwami M, Castro-Sánchez E, Husson F, Taiyari K, Zingg W, et al. Defining the user role in infection control. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2015, In press.

- Duerden B, Fry C, Johnson AP, Wilcox MH. The control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus blood stream infections in England. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 03/2015; 2(2). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv035.

- Duerden BI. MRSA: why have we got it and can we do anything about it? Eye 2012; 26: 218–221.

- NHS England. Guidance on the reporting and monitoring arrangements and post infection review process for MRSA bloodstream infections from April 2014 version 2. London: NHS England, 2014. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/mrsa-pir-guid-april14.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Lee YJ, Chen JZ, Lin HC, Liu HY, Lin SY, Lin HH, et al. Impact of active screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and decolonization on MRSA infections, mortality and medical cost: a quasi-experimental study in surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0876-y.

- Chaberny IF, Schwab F, Ziesing S, Suerbaum S, Gastmeier P. Impact of routine surgical ward and intensive care unit admission surveillance cultures on hospital-wide nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a university hospital: an interrupted time-series analysis. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(6):1422-1429. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn373.

- Vella V, Gharbi M, Moore LSP, Robotham J, Davies F, Brannigan E, et al. Screening suspected cases for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, inclusion criteria and demand. J Infect. 2015;71(4):493-495. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2015.06.002.

- Public Health England. Acute trust toolkit for the early detection, management and control of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. London: Public Health England, 2013. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/329227/Acute_trust_toolkit_for_the_early_detection.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Frieden T. Safe and sound: guarding against health care associated infections. Mediaplanet, 2015. Available from: www.futureofpersonalhealth.com/advocacy/safe-and-sound-guarding-against-health-care-associated-infections. (accessed 29.09.2015).

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x.

- Zingg W Castro-Sánchez E Secci F, Edwards R, Drumright L, Sevdalis N, Holmes. A Innovative tools for quality assessment: Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs (ICROMS). Public Health. 2015, in press.

- Fontana A, Frey J. Interviewing: the art of science. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editor. The handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 361–376. Available from: http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~pms/cj355/readings/fontana%26frey.pdf (accessed 29.09.2015).