Key points

- Across the UK, the number of children and young people experiencing mental health problems is growing. Mental health services are expanding, but not fast enough to meet rising needs, leaving many children and young people with limited or no support. Too little is known about who receives support and who might be missing out.

- National prevalence data suggest large variations in need by sex, age, and socioeconomic deprivation. But data on who is using services are only publicly available for NHS specialist mental health care and are not detailed enough to capture variation by these characteristics.

- This briefing presents analysis from the Networked Data Lab (NDL) about children and young people’s mental health. Led by the Health Foundation, the NDL is a collaborative network of local analytical teams across England, Scotland and Wales. These teams analysed local, linked data sources to explore trends in mental health presentations across primary, specialist and acute services.

- Analysis by local teams highlights three areas for further investigation, nationally and by locality: the rapid growth of prescribing and use of general practice, the mental health of young women, and marked socioeconomic inequalities.

- Prescribing and use of general practice: Local NDL teams found the use of GPs and medication for mental health problems is growing in their areas. In North West London, the monthly number of those aged 0–25 years with a mental-health related prescription or GP event (diagnosis, observation or referral) grew threefold between 2015 and 2021. In Grampian (Scotland), the proportion of those aged 0–24 years with mental health-related prescriptions increased from 4.7% in 2012 to 6.4% in 2019.

- Adolescent girls and young women: Around 25% of older adolescent girls and young women aged 17–22 years have a probable mental health disorder, a higher share than for any other group of children and young people. In Grampian, young women aged 19–24 years had the highest levels of antidepressant prescribing (17.9% in 2019). Adolescent girls aged 15–17 years had the greatest number of contacts with specialist mental health services in Leeds, as well as in Liverpool and Wirral, and were the group who most frequently presented with mental health crises to acute services in Wales.

- Socioeconomic inequalities: There is a stark contrast between areas of differing socioeconomic deprivation. In the 20% most deprived areas, compared to the 20% least deprived, crisis referrals were 60% higher among children and young people in touch with services in Leeds; there were twice as many prescriptions and 1.7 times as many referrals in Grampian; and there were close to twice as many crisis presentations to acute services in Wales.

- To inform national policy decisions and local service planning and delivery, the quality of data collection, analysis and the linkage of datasets across services and sectors need to be improved. More regular collection of robust and granular prevalence data would better support services to expand in line with need and target support. There must also be improvements in data quality for specialist services, closing of data gaps along the emergency crisis care pathway, and better linkage of data to understand experiences across care pathways. In England, the development of integrated care system (ICS) intelligence platforms – with fully linked, longitudinal datasets across primary, secondary, mental health, social and community care – will be a major step forward. Such platforms will allow ICSs to undertake similar analyses and learn from others.

- To understand whether children and young people can access support outside the NHS, particularly if turned away from specialist services, it is vital that data are collected on support services in schools and services funded by local government or the voluntary sector, and that these are linked to NHS data.

- Governments in all three countries have begun to recognise the scale of the challenge facing children and young people’s mental health. High-quality data and analysis will play a crucial role in targeting preventative interventions, planning services and improving children and young people’s mental health.

Introduction

The rising prevalence of mental health problems among children and young people over the past 20 years has become a growing concern in the UK., Governments in England, Scotland and Wales have published strategies to improve support and services in the NHS, schools and colleges, and the wider community.,, Mental health services across the UK were struggling to meet demand even before the COVID-19 pandemic.,, But since then, national lockdowns, disruptions to schooling and social life, and an increasing number of families in financial distress have exacerbated mental health struggles among children and young people.

The scale of this issue presents huge challenges for mental health services. For example, in 2021 1 in 6 young people aged 6–16 years in England had a probable mental health disorder – equivalent to 1.3 million individuals who might benefit from support. It seems unlikely that existing plans to increase the availability of services across the UK will be sufficient to provide support for all young people who need it.

Unmet mental health needs cause avoidable distress and disrupt a child or young person’s development at a crucial time in their lives. The case for early intervention is powerful, not only to prevent conditions from worsening but to improve the outcomes for people who develop enduring mental ill health.

The rising level of mental ill health among children and young people is also a threat to the future health and prosperity of society. Half of all lifetime cases of mental health disorders begin by age 15, and three-quarters of lifetime mental illness is experienced by the mid-20s., People with mental disorders have a reduced life expectancy of between 7 and 25 years, mostly because of physical health problems associated with mental ill health. A recent study estimates mental ill health costs the UK £118bn a year (5% of GDP in 2019), including the costs of treatment and lost earnings for people with mental illness and their informal carers. Addressing this requires funding and cross-government action, but it also requires reliable data and insight to enable services to plan for rising need.

About this briefing

In this briefing, we present analysis from the Networked Data Lab (NDL). Led by the Health Foundation, the NDL is a collaborative network of analytical teams from across the UK (see section About the Networked Data Lab). Using local expertise and unique linked datasets, our aim is to produce new insights into major challenges in health and care.

In Part 1, we provide some background on the trends in mental health disorders among children and young people and existing pressures on services, as well as an overview of the main policies in place in England, Scotland and Wales to improve children and young people’s mental health. In Part 2, we present findings from NDL partners: we examine trends and patterns of service use, including the use of general practice, specialist mental health care and acute services, along with differences by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. In Part 3, we show how local NDL teams used linked data to improve services in their area. We assess the NDL findings in the context of existing evidence and in the final section offer insights for national and local policymakers.

Part 1. Background and methodology

Prevalence of mental health disorders among children and young people

There is limited UK-wide evidence on the prevalence of mental health disorders among children and young people. In 1999 and 2004, the Office for National Statistics carried out two large surveys of young people aged 5–15 years living in England, Scotland and Wales. More recent comparable figures are available for England only: a survey of a cohort of 5–19-year-olds carried out by NHS England in 2017, with more recent follow-ups during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.,, The assessments are based on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a validated tool to assess different aspects of mental health, including problems with emotions, behaviour and hyperactivity.

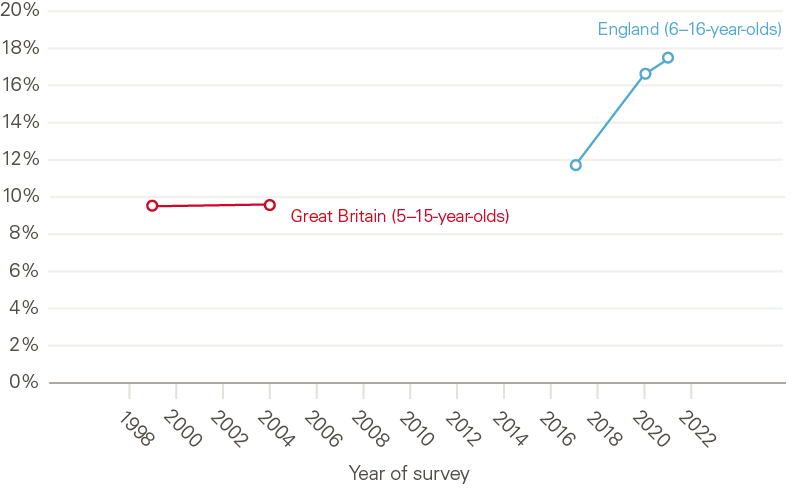

In 2021, 1 in 6 children and young people aged 6–16 years in England had a probable mental health disorder (17.4%), up from 1 in 9 in 2017 (11.6%, Figure 1). Among young women aged 17–19 years, this figure rises to 1 in 4 (24.8%) in 2021. Although prevalence estimates are not directly comparable over time due to changes in methodology, the indication that the prevalence of mental health conditions among children and young people in the UK has risen substantially over the past two decades is supported by other research., There is little doubt that the pandemic has contributed to this trend, with the mental health effects of pandemic restrictions greatest for children and young adults.,,,,

Which groups are at higher risk?

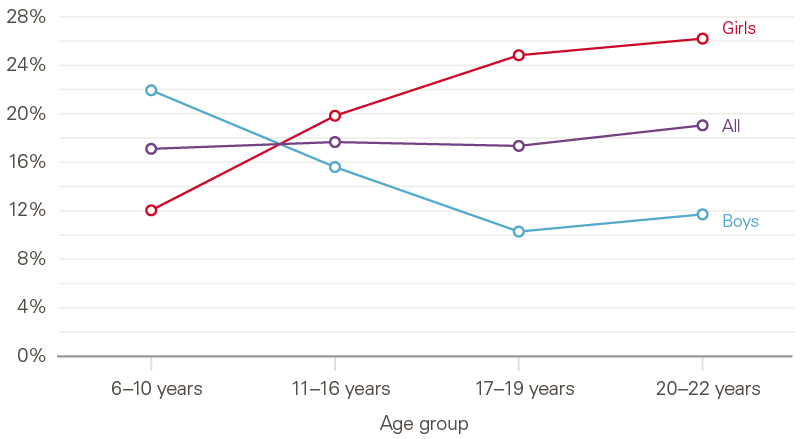

A 2021 survey in England found that among young children, boys are at higher risk of developing a mental health disorder than girls (Figure 2). This trend reverses in adolescence and girls are at higher risk in other age groups, with young women most strongly affected. The national surveys are limited in their ability to fully capture other demographic characteristics that might signal increased risk, but other studies have shed light on this, including:

- Ethnicity: There are disparities in the prevalence of mental health disorders between children and young people from different ethnic backgrounds., White adolescents tend to report worse mental health than young people from other ethnic groups, but rates of attempted suicide at age 17 were similar across ethnic groups. A better understanding of these differences is still limited by the often small sample size of survey respondents from minority ethnic groups, cultural differences in self-reported mental health, and because heterogenous ethnic groups are often grouped into a single ‘non-white’ category, which may be masking underlying differences. There are known differences in referral routes to specialist mental health services, with minority ethnic young people more likely to be referred through compulsory pathways (eg social care, education, youth justice) rather than voluntary pathways., Therefore, the under-representation of children from minority ethnic backgrounds in UK mental health services might actually represent unmet need, rather than lower prevalence.

- Sexual orientation: There are also large disparities by sexuality, with the highest reported prevalence of serious mental health outcomes for LGB+ young people, especially depressive symptoms and self-harm.,

- Deprivation: The link between socioeconomic deprivation and child mental health problems is well documented,, with children and young people living in lower income households more likely to have poor mental health.,

Figure 1: Percentage of children and young people with a probable mental health disorder in Great Britain in 1999 and 2004 and England in 2017, 2020 and 2021

Source: 2017–2021 Mental Health of Children and Young People in England Survey; 1999 The mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain; 2004 Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain. Between 2017 and 2021, 6 to 16 year olds are considered to have a probable mental health condition based on answers to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. In 1999 and 2004, survey responses were analysed by clinicians using a case vignette approach.

Figure 2: Percentage of children and young people with a probable mental health disorder in England, 2021

Source: 2021 Mental Health of Children and Young People in England Survey.

Policies in England, Scotland and Wales

Governments in all three countries have recognised the importance of good mental health for children and young people, and the rising prevalence of mental health problems in these age groups. In the past decade, all have published cross-government strategies to improve services across sectors, not just those provided by the NHS (Box 1). These strategies have several strands in common, including:

- more provision of mental health and wellbeing support in schools and the community outside the NHS, including a focus on prevention

- improving access to (and reducing waiting times for) specialist Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS)

- improved crisis care

- extending mental health services beyond age 18, to 25 or 26 (Scotland).

The structure of services

Although strategies to improve services vary between Scotland, England and Wales, services are structured in a broadly similar way. Until recently, services have been grouped into four ‘tiers’, although some areas, including England, are increasingly moving away from this model. Nevertheless, the scheme is a useful way of capturing the scope and source of services. Tier 1 generally comprises services designed to prevent mental health problems or respond to less severe mental health problems and includes NHS services (eg general practice), services funded by local government (eg youth services) or via schools (counselling). Although the composition of teams within tiers 2 and 3 may vary locally, they comprise specialist services for children and adolescent mental health (CAMHS), delivered in an outpatient setting. Tier 4, the most specialised services, includes inpatient care.

While data are collected across these four tiers, most are not routinely published. There are very limited data from general practice, and no publicly available data relating to mental health provision in schools or services funded by local government or the voluntary sector. All three countries routinely capture data on hospital admissions, and detentions under the Mental Health Act 1983.

Pressures on services

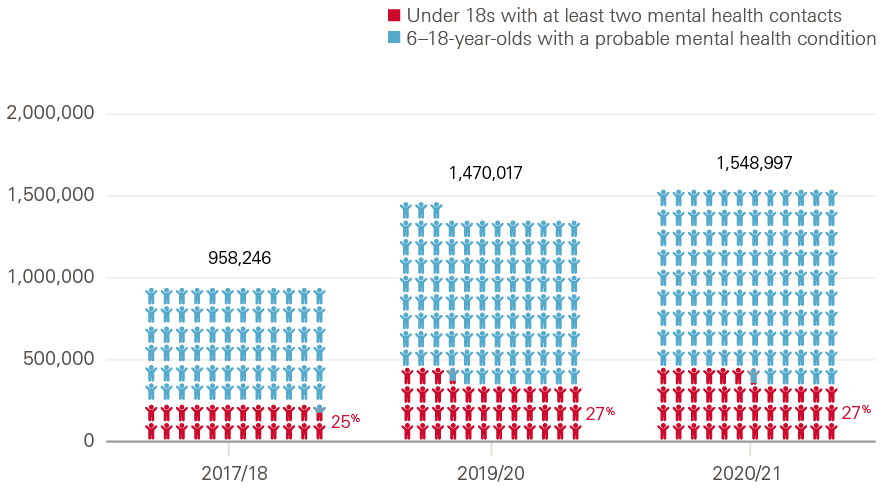

Although NHS mental health service capacity has been expanded over recent years, it is still vastly outstripped by demand. In England, the number of children and young people in contact with CAMHS rose by 46.6% between 2019 and 2021. However, due to the rising prevalence of mental health disorders, overall access to support remains low. In 2020, 27% of children and young people who needed support were receiving it, compared to 25% in 2017 (Figure 3).

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely contributed to rising demand. After an initial slowdown early in the pandemic, new referrals to CAMHS in England reached a peak of 87,000 per month in 2021, the highest number since the start of the data series in 2019. Certain services, such as support for eating disorders, have seen a clear rise in cases since the pandemic began while others, such as urgent crisis referrals, have been rising since before COVID-19.

Lengthening waiting times are a symptom of demand rising faster than services can expand. The available data, which vary substantially between nations due to different waiting time and access targets, paint a mixed picture. In Scotland, where the target is for 90% of children and young people to start treatment within 18 weeks, only 70.3% did so during the last quarter of 2021, a decrease compared with 73.1% in the same period in 2020. In Wales, on average 46% of first appointments took place within 4 weeks in 2021, a decrease from 65% in 2020. In England, the average waiting time for those accepted into services was 32 days in 2020/21, down from 43 days in in 2019/20. However, this overall improvement may be masking large geographical variation, with average waiting times in some areas being as long as 81 days.

Figure 3: Number of children and young people with a probable mental health disorder and number in contact with CAMHS in England

Source: NHS Digital Mental Health Bulletin, Mental Health of Children and Young People in England Survey. The estimated number of people with a probable MH condition comes from: (population 6-16)*(proportion of 6-16 with probable MH)+(population 17-18)*(proportion of 17-19 with probable MH).

In England, waiting time standards currently only exist for access to treatment for eating disorders, which is highly specialised and represents a small part of mental health services for children and young people. The target is for 95% of patients to start treatment for eating disorders within 4 weeks of referral for routine cases, and within 1 week for urgent cases. In 2021, on average only 49.0% of routine cases and 39.1% of urgent cases started treatment within these times. A 4-week target from referral to ‘help’ for children presenting to community based NHS services has been piloted in England, with plans for national implementation.

Importantly, in all three countries, the figures do not capture children and young people not accepted for treatment in the first place. There are currently no data on what happens to children and young people referred but not accepted for treatment, such as whether they accessed other services or went without help. However, unmet need is likely to be significant given the large gap between prevalence and CAMHS treatment rates.

Aims of this analysis

Meeting the mental health needs of children and young people in all three countries depends on those planning and providing services having a clear understanding of who is using what kinds of services (including by age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic background as a minimum) and how these data compare with expected levels of need derived from prevalence surveys (and other research evidence).

Much of the data used to monitor children and young people’s use of services in all three countries focuses on specialist mental health services (rather than including eg primary care or emergency services), and does not include important characteristics such as age or sex.

A primary aim of this research is to use local analysis of linked data to shed more light on who is using children and young people’s mental health services. A second aim is to see if the observed patterns could indicate where there might be unmet need that would allow for better targeting of services in the future.

Approach and methods

Launched in 2019, the Networked Data Lab (NDL) is a collaborative network of analytical teams across the UK. It aims to provide local and national health system leaders with fresh insights to improve the UK’s health and care systems, including reducing inequalities in health and access to services.

The programme is led by the Health Foundation and comprises the following partners:

- NDL Grampian: The Aberdeen Centre for Health Data Science (ACHDS) which includes NHS Grampian and the University of Aberdeen

- NDL Wales: Public Health Wales, Digital Health and Care Wales (DHCW), Swansea University (SAIL Databank) and Social Care Wales (SCW)

- NDL North West London: Imperial College Health Partners (ICHP), Institute of Global Health Innovation (IGHI), Imperial College London (ICL) and North West London CCGs

- NDL Liverpool and Wirral: Liverpool CCG and Healthy Wirral Partnership

- NDL Leeds: Leeds CCG and Leeds City Council.

Analysis approach

The NDL uses a federated analytics approach meaning that analysis is performed locally, eliminating the need for patient data to leave secure local systems. This approach allows us to gain new insights from rich linked datasets that are not available at the national level. It also enables the NDL to benefit from local data expertise and understanding of the local context brought by analysts, clinicians and patients.

To maximise the value of locally held data, the NDL uses a mixture of standardised metrics and bespoke approaches designed by individual partners according to local needs and data availability. For each analysis topic, we look for an appropriate balance between standardisation and customisation. For children and young people’s mental health, the heterogeneity of locally available datasets led us to choose a flexible approach, where each partner designed bespoke analyses to fully take advantage of local data and linkages. Research questions were identified and prioritised by NDL teams through engagement with local patients and their families, commissioners, local authorities and service providers. Patient and public involvement was central in shaping research questions from a service user perspective and in communicating findings. The research covered a wide range of topics, from inequalities in access to services to the role of the ambulance service in mental health crises.

A summary of the research questions we tackled and the datasets we used is provided in Table 2. NDL partners collaborated closely by sharing their approaches to creating and processing new data sources and linkages, including information governance, as well as methodology. The results and insights were then shared across the network and synthesised for this briefing. A full description of methods can be found in the accompanying technical appendix and the analysis code is available for the wider analytical community.

Table 1: New and existing mental health datasets used by the NDL

|

NDL partner |

Questions |

Datasets and linkages |

|

Grampian (Scotland) |

How have mental health prescribing and referrals to specialist mental health services changed over time? Which sociodemographic groups are most likely to receive medication, to be referred for specialist treatment or to be accepted for treatment? |

Grampian Data Safe Haven (DaSH) Prescribing Information System (PIS) dataset CAMHS data |

|

Wales |

What are the trends in mental health crisis presentations across the acute health care system and their outcomes? What are the differences in crisis presentations between sociodemographic groups, and which groups are at highest risk? |

SAIL Databank Emergency Department Dataset (EDDS), Patient Episode Database Wales (PEDW), Wales Longitudinal General Practice (WGLP), linked to the Welsh Ambulance Service Trust (WAST) dataset and the Substance Misuse Dataset (SMDS) |

|

North West London |

How do usage patterns of different mental health services vary between sociodemographic groups? |

Discover Now Hospital data from Secondary Uses Service (SUS), linked to GP events and prescriptions data, and Mental Health Trusts (CNWL/WLMHT) data |

|

Liverpool and Wirral |

How do usage patterns of different mental health services vary between sociodemographic groups? How can linked data across services help to identify areas with potential unmet support need? |

Liverpool and Wirral Data Model Hospital data from Secondary Uses Service (SUS) and Emergency Care Dataset (ECDS), linked to Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS) |

|

Leeds |

What are the differences in referrals and crisis referrals to specialist mental health care between sociodemographic groups? Which groups are at highest risk of disengaging during the transition to adult mental health services? |

Leeds Data Model Hospital data from Secondary Uses Service (SUS), linked to GP events and prescriptions data and the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS) |

* The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adolescent as any person between ages 10–19 years.

† NHS England also uses the abbreviation CYPMHS (children and young people’s mental health services) to describe all services that work with children and young people who have difficulties with their mental health or wellbeing. In England, CAMHS is used to describe the main specialist NHS community service within the wider CYPMHS. Scotland and Wales primarily use the term CAMHS to describe available services.

‡ These figures differ from access rates published by NHS England as these are calculated relative to the 2004 prevalence estimate of mental health disorders that applied when the target was set. See: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/cyp/

§ This may include immediate advice, support or a brief intervention, help to access another more appropriate service, the start of a longer term intervention or agreement about a patient care plan, or the start of a specialist assessment that may take longer.

Part 2. Patterns of service use

Mental health care in general practice

GPs are often the first port of call for children and young people with a new health concern. They play a key role in recognition and management of child and adolescent mental health problems and can provide referrals to specialised mental health services.

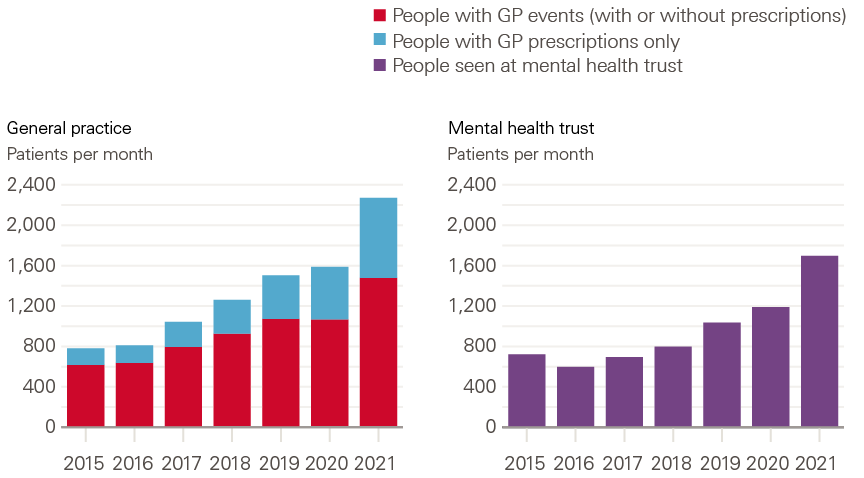

Analysis by NDL partners in North West London found that GPs account for an increased proportion of mental health-related service use by children and young people (Figure 4). Since 2015, the average monthly number of young people with a GP event or prescription related to mental health conditions increased by 194%. Over the same time, the number of young people seen at mental health trusts in the area increased by 138%. Even after adjusting for population growth, the rate of service use in both types of settings increased almost twofold.

Figure 4: Average monthly number of children and young people aged 0–25 years in North West London with a mental health-related GP event, and/or a mental health prescription, or seen at a mental health trust, 2015–2021

Source: NDL North West London analysis of Discover data.

Children and young people seen at a mental health trust for any mental health condition were mostly younger adolescents (Figure 5). In contrast, the vast majority of young people with a mental health-related GP attendance or prescription were older adolescents and young adults. This may partly be because GP diagnoses for conditions such as ADHD, which are more common in younger children, were not included in the analysis. Younger children may also be more likely to be referred to mental health services by schools.

Figure 5: Number of children and young people in North West London seen for mental health reasons in general practice or mental health trusts, by age group, 2019

Source: NDL North West London analysis of Discover data.

These findings suggest that in North West London, general practice has been playing an increasing role in the management and care of children and young people with mental health conditions. There is evidence that this trend exists across the UK, and that it is likely a symptom of both increasing need and overstretched specialist services.,, Most children and young people with mental health needs still receive no specialist support, and those who do often face long waits before treatment begins. The Children’s Commissioner found that in 2020/21 close to a quarter of referrals to CAMHS in England were closed before treatment started, and there is anecdotal evidence that the threshold for support may have risen further.,, For many children and young people who do not meet the criteria for specialist care, general practice may therefore be the main and only available source of mental health support.

Prescriptions for mental health medications

The frequency of antidepressant prescribing among children and adolescents in the UK has nearly doubled between 2006 and 2015. The group that accounted for most of this rise in prescribing was adolescent girls (aged 15–17 years) who were also more than twice as likely as boys of the same age to be prescribed antidepressants. A survey by NHS England in 2017 found that 1 in 50 (2.5%) of 5–19-year-olds were taking medication for a mental health-related problem. Among 17–19-year-olds, this figure rose to 1 in 20 (5.0%), with the most common type of medication being antidepressants. Children and young people with a hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were the group with the highest prescribing rates (45.9%). Little published data are available on more recent trends, or on variation in mental health prescribing for children and young people by other demographic or socioeconomic characteristics.

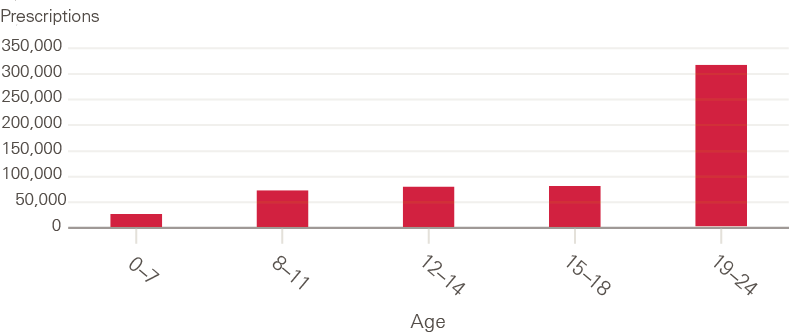

NDL partners in Grampian analysed comprehensive, longitudinal local data on mental health prescriptions made in the community, using Scotland’s PIS dataset. They found that the percentage of children and young people (aged 0–24 years) with mental health-related prescriptions increased from 4.7% in 2012 to 6.4% in 2019. Prescribing rates were found to increase rapidly with age, driven by prescribing of antidepressants in the 19–24 age group (Figure 6). The inclusion of this age group also likely explains the higher prevalence of prescribing found in this analysis, compared with the earlier estimates for England. Young adults aged 19–24 years alone accounted for 55% of prescriptions.

Figure 6: Number of mental health prescriptions for children and young people in Grampian by age group, 2012–2020

Source: NDL Grampian analysis of Scotland's Prescribing Information System (PIS) data.

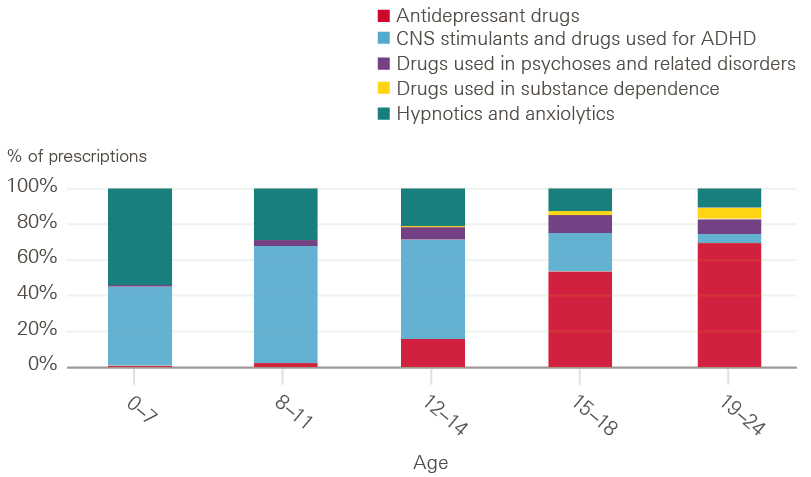

Figure 7: Types of mental health prescription for children and young people in Grampian by age group, 2012–2020

Source: NDL Grampian analysis of Scotland's Prescribing Information System (PIS) data.

NDL partners' analysis also found large age-related differences in prescribing between male and female children and young people. Children younger than 14 years were primarily prescribed medication for ADHD and close to 80% of prescriptions in this age group were for boys. Young adults aged 19–24 years were mostly prescribed antidepressants and 62% of prescriptions for young adults were for women. In 2019, 17.9% of young women aged 19–24 years had a prescription for antidepressants, compared to 9.1% of young men in the same age group. The Grampian team was also able to examine mental health-related prescription rates by area-level socioeconomic deprivation. They found that children and young people in the most deprived areas had twice as many prescriptions as in the least deprived areas (58 prescriptions per year per 100 children in the 20% most deprived areas, compared with 27 in the 20% least deprived areas).

Their findings about the rise in prescription rates are consistent with the observed rising prevalence of mental ill health, as are the findings about the variations in age and sex, for example the high rates of antidepressant prescribing for young adults. But these data beg contextual information not consistently recorded in administrative health care data, for example whether those receiving prescriptions for depression are also accessing appropriate psychological therapies and being regularly monitored according to NICE guidelines.

Referrals and contacts with specialist care

National prevalence data and other research suggest that mental health support needs vary by age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic circumstances. In the absence of more granular information on underlying need among different population groups, local bodies responsible for planning and delivering specialist CAMHS need to understand such variations, to better target services according to need.

Local data analysis of this kind can highlight variation that might indicate services are not meeting needs. In the West Midlands, for example, analysis by the Strategy Unit found that black children and young people had more frequent contact with mental health services but shorter contact time, had the highest re-referral rates and were most likely of all ethnic groups to have prolonged service needs. While NDL teams found that ethnicity data were too poor to use, and interpreting them was challenging due to missing data on population size by ethnicity, they did find striking differences in the use of services by age, sex and deprivation.

Referrals and contact patterns by age and sex

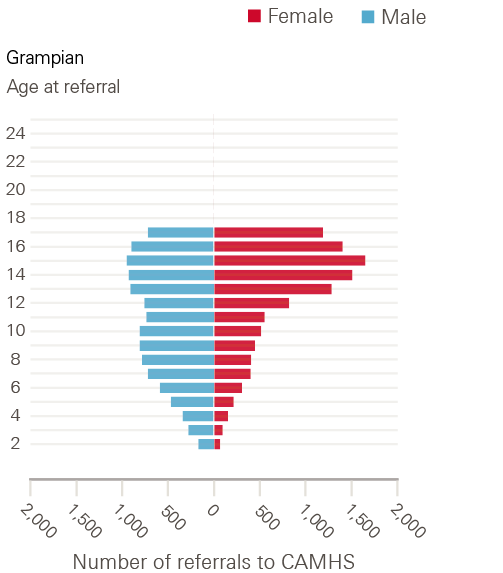

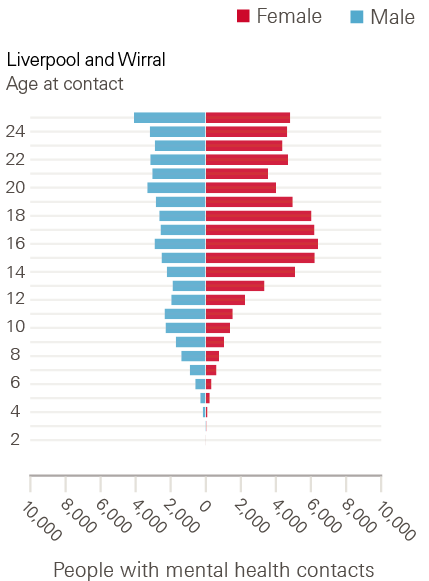

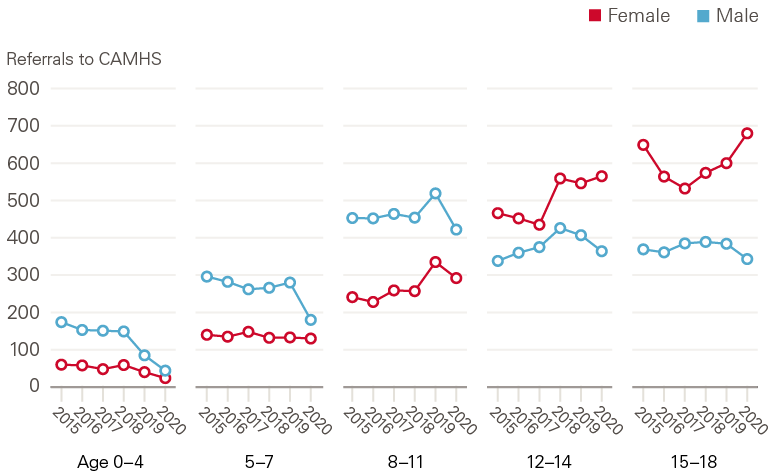

Despite differences in data sources and analytical approaches, NDL partners found similar patterns of mental health service use by age and sex. The NDL team in Grampian examined the number of referrals to specialist mental health services for children and adolescents (aged 2–17 years). Two NDL partners in England analysed the number of care contacts with specialist mental health services (including those aged 0–25 years in Liverpool and Wirral, and 11–25 years in Leeds).

Among children younger than 12 years, boys accounted for the majority of mental health referrals in Grampian and of care contacts in Liverpool and Wirral (Figure 8). Consistent with the national prevalence estimates of mental health disorders in England, from the age of 12 years girls were more likely than boys to be referred to or receive specialist mental health care, with particularly stark sex differences around the time of adolescence. Referrals and contact rates for adolescent girls increased with every year of age, up to the ages of 15 and 16, respectively. In Leeds, adolescent girls accounted for 72.6% of all contacts of those aged between 15 and 17 years at the time of referral.

Research has found plenty of evidence of gender disparities in mental health among young people. A large study of primary care records in England found that the incidence of adolescent girls presenting with self-harm has been rising sharply since 2010, and children and adolescents who harm themselves were also found to be at an increased risk of suicide.

Figure 8a: Number of referrals to CAMHS for children and young people aged 2–17 years in Grampian by age at referral, 2015–2021

Source: NDL Grampian analysis of CAMHS data.

Figure 8b: Number of children and young people aged 0–25 years with mental health contacts in Liverpool and Wirral by patient age, 2019–2021

Source: NDL Liverpool and Wirral analysis of MHSDS, SUS and ECDS data.

Transition to adult mental health services (AMHS)

Adolescence and young adulthood are often turbulent and vulnerable times, marked by key developmental milestones such as leaving school and moving out of the family home. Both the incidence of mental illness and the risk of disengagement from mental health services are high in this age group. In addition, between age 18 and 25 young people are required to transition to adult mental health services (AMHS), which may have different acceptance thresholds. This service ‘cliff edge’, and the often poor support offered during transition, has been a long-standing concern.

While there is little quantitative evidence on the proportion of young people who successfully transition to adult services, qualitative work has suggested that up to a third of young people are ‘lost from care’ during this period, with another third facing disruptions to care. Previous research also found that young people struggle with the cultural shift between CAMHS and AMHS, from the nurturing environment in CAMHS, which emphasises the family unit, to a more impersonal atmosphere in adult services, which are more likely to treat young people as autonomous adults and offer limited family involvement in favour of personal privacy.

While this transition typically occurs between ages 18 and 21, there is large variation between areas in the age ranges covered by children and young people’s services, and in how young people are supported beyond CAMHS. Due to the poor quality and completeness of mental health data, our understanding of young people’s experience of transition and how services can improve transitions is extremely limited.

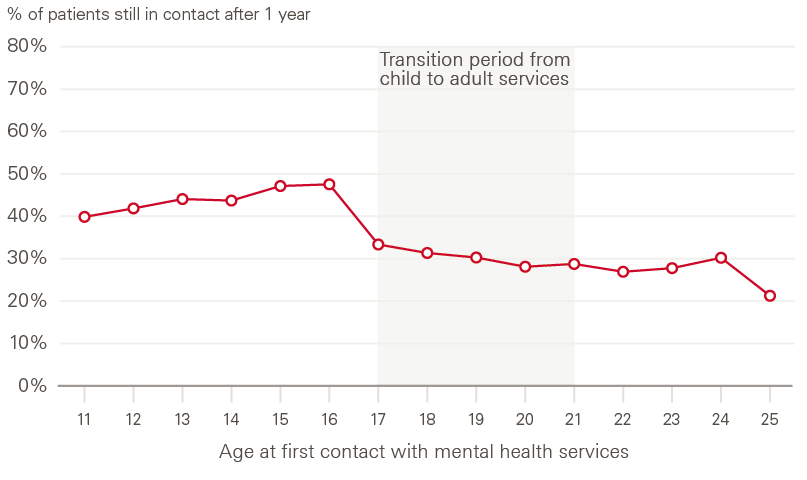

Although NDL teams attempted to examine this using patient-level linked data, poor quality and completeness of data fields prevented them from reliably identifying whether recorded care contacts were with child and adolescent or adult mental health teams. As a proxy measure to study the relationship between patient age and ongoing engagement with the service, NDL partners in Leeds quantified the proportion of young people still in contact with services after 1 year, shown by age at first contact (Figure 9). They found that this proportion decreased at around age 17, when young people approach transition age, and remained lower for older ages. This could indicate that young people around transition age are more likely to lose contact with services or that the length of treatment may be shorter for adult mental health services.

Figure 9: Percentage of children and young people in Leeds still in contact with services 1 year after their first contact, by age at first contact

Source: NDL Leeds analysis of MHSDS data.

Socioeconomic deprivation

There is considerable evidence of the links between socioeconomic deprivation and child mental health problems., Responses to surveys in England show a clear correlation between lower parental income and poorer mental health among children and young people. However, data on the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and mental health service use among children and young people are currently only available for Scotland and remain experimental. These data show a socioeconomic gradient in referral rates, with rates being consistently higher for people in the most deprived areas.

To explore this relationship in more detail, NDL partners were able to link patient records to the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) from England (2019), Scotland (2020) and Wales (2019), based on the area where patients lived. They then compared mental health referrals, contacts and outcomes between young people living in the 20% most deprived areas and the 20% least deprived areas.

Analysis of referrals to specialist mental health care from the NDL team in Grampian found that there were 1.7 times more referrals for young people in the most deprived areas compared with young people in the least deprived areas. Young people from the most deprived areas were also younger when referred: the average age at first referral in the most deprived areas was 10.4 years, compared with 11.6 years in the least deprived areas.

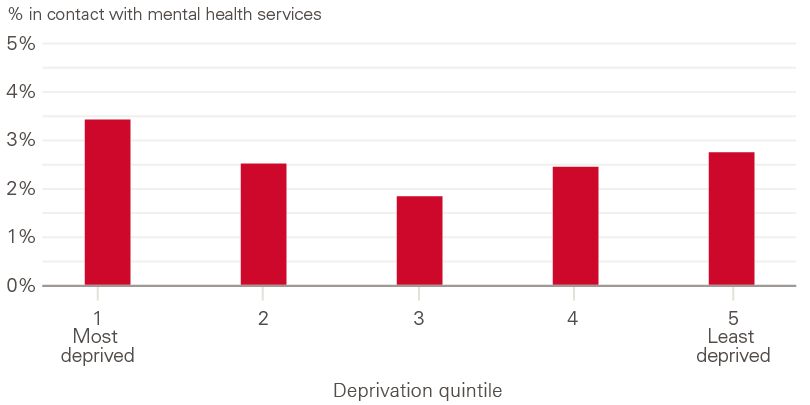

The NDL team in Leeds found similar patterns in care contacts, with children and young people living in the most deprived areas most likely to be in touch with specialised mental health services. Interestingly, they also found a high proportion of young people in contact with services in the least deprived areas, which warrants further investigation, and may indicate differences in self-recognition of support need or in the ability to navigate access in a complex system (Figure 10). This hypothesis is supported by previous analysis highlighting that children and young people in less deprived areas are more likely to self-refer to mental health services. It is important to note that none of the data used for this analysis capture privately funded mental health services, which will affect the steepness of the deprivation gradient, as they may be more frequently used by children and young people in affluent areas.

Figure 10: Percentage of children and young people aged 11–25 years in Leeds who were in contact with CAMHS by IMD quintile, 2017–2020

Source: NDL Leeds analysis of MHSDS data.

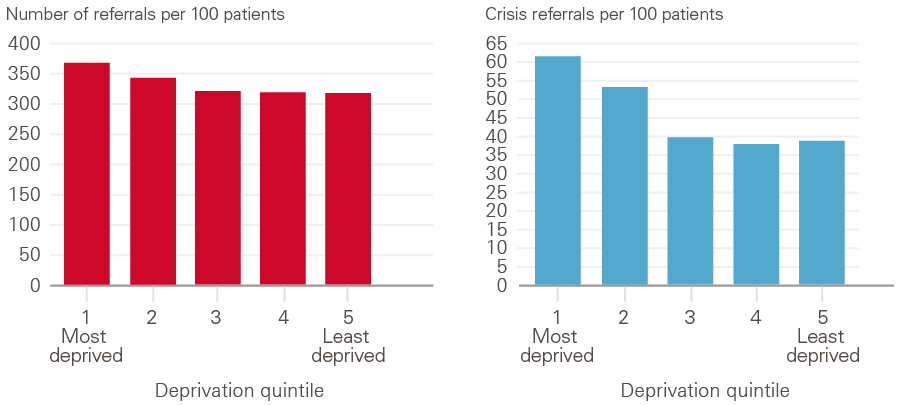

As national estimates on the prevalence of mental health disorders are not available by socioeconomic deprivation, it is difficult to draw conclusions about how these patterns relate to underlying support need. However, among existing patients aged 11–25 years in the most deprived areas, the rate of both referrals and crisis referrals in Leeds was higher (Figure 11). The difference in crisis referrals is particularly pronounced, with 60% more referrals for patients in the most deprived areas than for patients in the least. This may indicate that children and young people in more deprived areas are not only more likely to have mental health support needs, but that these needs may also be more severe.

Figure 11: Number of referrals and number of referrals to a mental health crisis team (crisis referral) per 100 patients aged 11–25 years in Leeds by IMD quintile, 2016–2021

Source: NDL Leeds analysis of MHSDS by NDL Leeds.

These findings reinforce the importance of better understanding how children and young people navigate the complex referral pathways and how this varies by socioeconomic deprivation. For example, analysis by the Strategy Unit found that children and young people in more deprived areas are more likely to have their referral deemed ‘unsuitable’, have shorter contact time during an appointment and are more likely to be re-referred back into services within a year, despite a higher percentage completing their treatment plans.

Mental health crisis presentations

For children and young people experiencing mental health crises, timely access to appropriate support is essential. Children and young people may present in crisis at many different entry points to the NHS, and not all may require hospital care. In order to target action to improve crisis support, service planners and decision makers need a better understanding of the incidence of mental health crisis presentations, and which children and young people are at a high risk. Pioneering analysis from NHS Wales has already demonstrated how examining crisis presentations across the emergency care pathway can inform a more joined-up, whole-systems approach to crisis care. However, the data sources currently available at the national level only provide insight into small parts of the crisis care pathway, such as A&E attendances or hospital admissions, making it challenging to assess the scale of demand and whether young people’s needs are being met in an effective and timely manner.

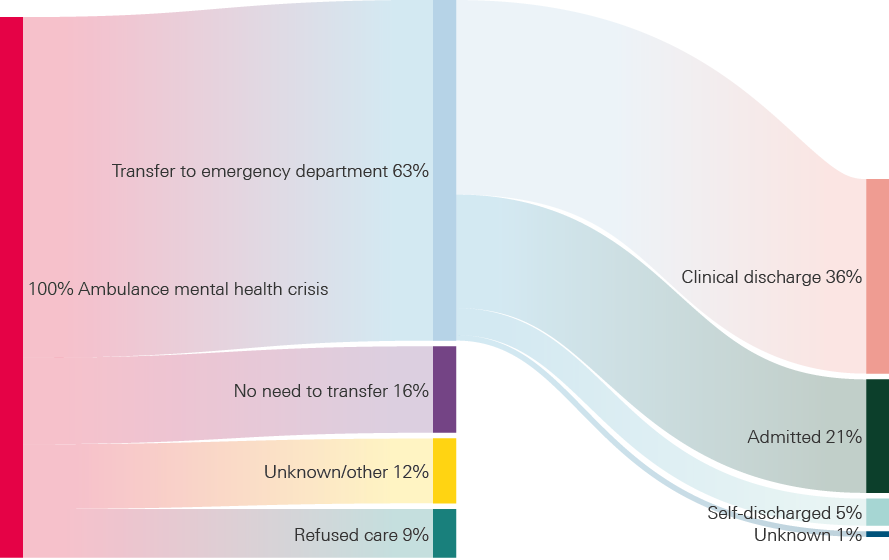

Building on their previous work, NDL partners in Wales created a novel linkage of routine secondary care data with data from the Welsh Ambulance Services Trust (WAST). A strength of this approach is that the data are national and capture all ambulance callouts in Wales, allowing a more comprehensive picture of acute care use by children and young people experiencing mental health crises.

Figure 12: Children and young people aged 11–24 years presenting to WAST with mental health crises by outcome, 2018–2020

Unknown/other includes cases where clinicians requested transport, hoax calls or erroneous data, no patient found at the scene or ambulances were cancelled pre-arrival.

Source: NDL Wales analysis of Welsh Ambulance Service Trust, emergency department and admissions data.

The analysis included 4,638 ambulance callouts related to children and young people aged 11–24 years presenting with mental health crises between 2018 and 2020, including self-harm, suicide attempts, overdose, psychosis, and other serious mental illnesses requiring urgent care. The analysis found that in 2 out of 3 cases (63%), patients were subsequently transferred to an emergency department (Figure 12). Of these, the majority were not admitted to hospital (but they might have been referred to outpatient services or to their GP). Overall, only 21% of ambulance callouts related to mental health crises resulted in admission to hospital. Some of this difference may reflect challenges in interpreting ambulance callout and emergency attendance data.

Improving the completeness and quality of these data has the potential to provide much richer information on the care pathways for children and young people in crisis attended to by ambulance. The findings highlight that data available at the national level, such as A&E attendances and emergency admissions, only capture a fraction of mental health crises that present to ambulance services. Just under 1 in 10 patients (9%) attended by ambulance teams refused care. To improve service planning and provision, it will also be important to understand the underlying reasons why some young people refused treatment.

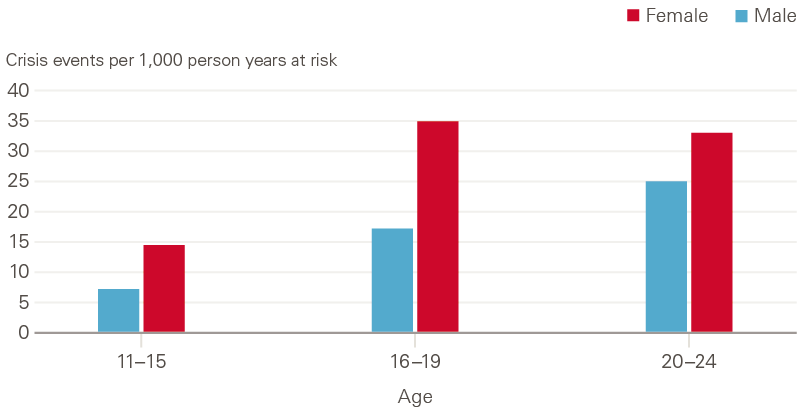

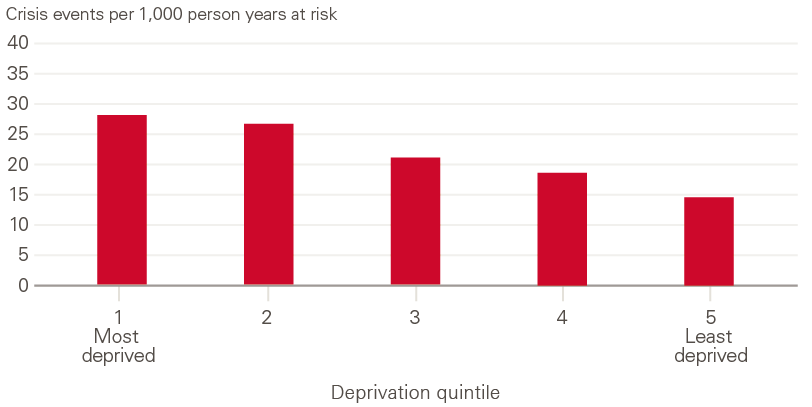

The Wales NDL team also investigated patterns in crisis events in more detail, including ambulance attendances, visits to A&E and emergency hospital admissions. They found that in 2019, girls (11–15 years) and young women (16–19 years) were twice as likely to present in crisis than boys and young men of the same age (Figure 13). The rates of crisis events generally increased with age, but they were highest among young women aged 16–19 years. Crisis event rates were also strongly patterned by socioeconomic deprivation, with children and young people living in the 20% most deprived areas in Wales having almost double the rate of crisis events compared with those living in the 20% least deprived areas (Figure 14).

Figure 13: Rates of mental health crisis events among children and young people in Wales, by age and sex, 2019

Mental health crisis events include WAST attendances, A&E attendances, and emergency hospital admissions.

Source: NDL Wales analysis of Welsh Ambulance Service Trust, emergency department and admissions data.

Figure 14: Rates of mental health crisis events among children and young people in Wales, by Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) quintile, 2019

Mental health crisis events include WAST attendances, A&E attendances, and emergency hospital admissions.

Source: NDL Wales analysis of Welsh Ambulance Service Trust, emergency department and admissions data.

** GP events include mental health diagnoses, observations and referrals to other mental health services. For a full list of codes for events and prescriptions see the technical appendix.

†† Anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, personality disorders, schizophrenia, self-harm, or harmful thoughts.

‡‡ According to NICE guidelines, antidepressants (fluoxetine) should only be offered to children and young people (5–18-year-olds) if moderate to severe depression is unresponsive to a specific psychological therapy after 4–6 sessions, and then only in combination with concurrent psychological therapy.

§§ This analysis was performed by linking patient-level prescription information to quintiles of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD, https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020).

¶¶ In Grampian, this included referrals to CAMHS, and in Leeds, and Liverpool and Wirral it included referrals to tier 2 and above services included in the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS).

*** Between 2015 and 2021, there were 29.1 referrals per 100 children living in the 20% most deprived areas and 17.1 referrals per 100 children living in the 20% least deprived areas.

††† Referrals to tier 2 and above services included in the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS).

‡‡‡ The proportion of referrals that were accepted were similar across deprivation quintiles (not shown).

Part 3. Improving patient care using linked data

Local analysis of linked data can provide a much more complete picture of who is using a range of services for mental health problems, and also enabled NDL partners to inform service improvement in their local area. This section presents examples of local impacts the NDL partners’ analysis had on service planning, identification of potential unmet need and the quality of mental health data.

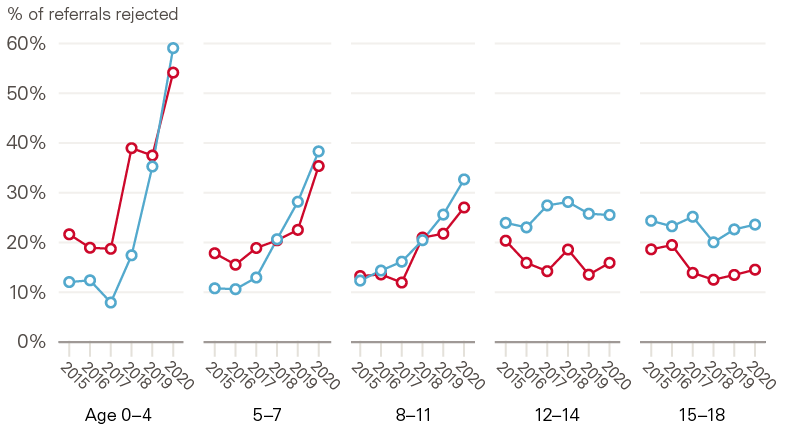

Detecting emerging inequalities in accessing specialist treatment in Grampian

The NDL team in Grampian wanted to better understand trends in referrals to CAMHS outpatient specialists and the likelihood of referrals for treatment being accepted by the provider. Their analysis shows that the overall number of referrals made for children and young people aged 2–17 years in the NHS Grampian Health Board increased between 2015 and 2021. The resulting pressures on service capacity led to a rise in the proportion of referrals that were rejected, from 18% in 2015 to close to 24% in 2020.

The analysis also showed a shift in who was being treated over this period. While adolescent girls accounted for most of the increase in referrals over time, there was a steady decline in referrals for boys between 2018 and 2020 (Figure 15, top). Over the same period, rejection rates for younger children increased, while the likelihood of older children and adolescents being accepted for treatment remained broadly the same (Figure 15, bottom). Since boys make up the majority of young children referred for treatment, boys were more likely to be rejected than girls: 40% of referrals for boys were rejected in 2021, compared with 25% of referrals rejected for girls.

Consulting with the CAMHS clinical team, Grampian learned that it had increased its focus on supporting the growing needs of children and young people with complex anxiety or depression, which are more common in older children and adolescents. In response to these findings, the CAMHS team recognised that support for younger children with conditions such as conduct disorders, ADHD and hyperactivity disorders, or neurodevelopmental needs required investment. Local CAMHS services are now in the process of hiring two consultant psychiatrists. In addition, Grampian Health Intelligence, who are responsible for supporting service planning, performance and improvement at area level, have established a multi-agency team focusing on support for vulnerable children.

This project shows how linked data, combined with local expertise on service delivery, can help target improvements to reduce unmet need. While the Children’s Commissioner for England found that overall rejection rates have been decreasing, they also highlighted enormous geographical variation, with rejection rates varying between 8% and 41% between local areas. The findings also emphasise the need for regular and granular data on who is being accepted for treatment to better understand unwanted variation. Data of this kind are currently only publicly available for Scotland.

Figure 15: Number of referrals to outpatient specialist mental health services and referral rejection rates for children and young people aged 2–17 years in Grampian, 2015–2020

Source: NDL Grampian analysis of CAMHS data.

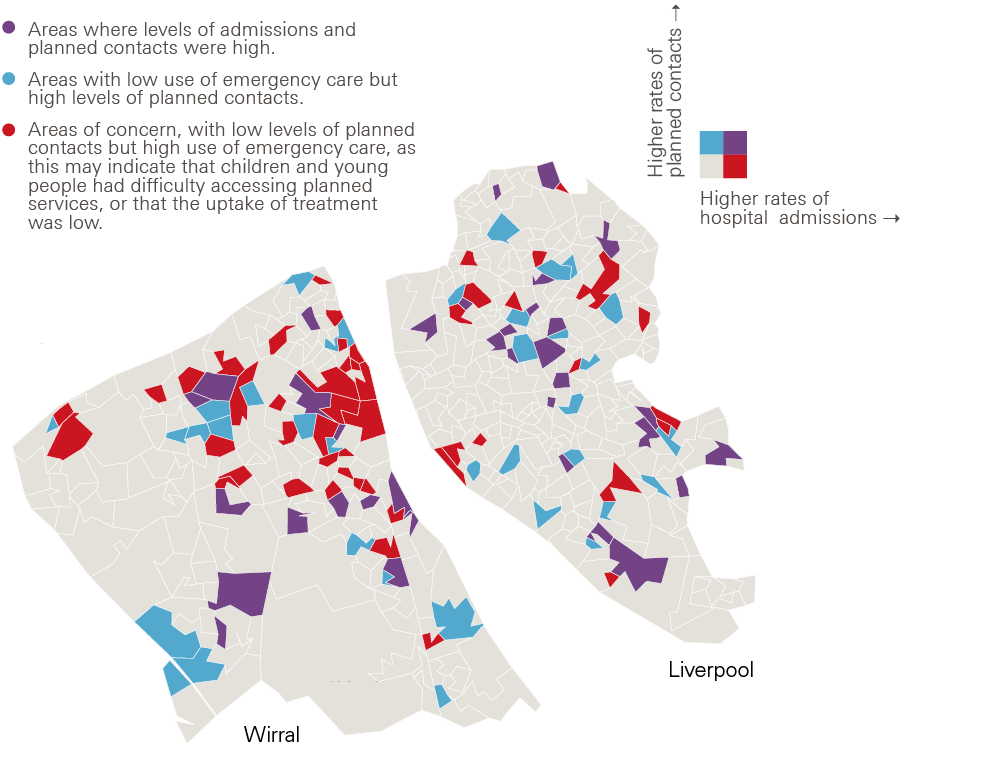

Identifying pockets of unmet need in Liverpool and Wirral

The NDL team in Liverpool and Wirral explored area-level associations between use of routine mental health services and the frequency of emergency hospital admissions related to mental health (self-harm, alcohol or substance abuse, and eating disorders). Mental-health related emergency admissions are often the result of a crisis, frequently involving serious self-harm or suicide attempts.

The team computed rates of planned contacts with NHS services in the community and of mental health-related hospital admissions for children and young people up to the age of 25 years, in relation to the number of young people living in each area. In this way, they were able to identify areas with potential unmet mental health need: neighbourhoods with relatively low levels of planned contacts but higher levels of emergency admissions (light red shaded areas in Figure 16). This may be due to more severe need, or poor access to or uptake of treatment. The team is developing further analysis to better understand underlying reasons and identify cohorts at risk.

Data insights such as these, which require granular data across services, can help local service planners focus their efforts on areas most in need, aiming to provide early support to children and young people with mental health problems before they reach crisis point. In Wirral, these findings are now informing the commissioning of the local emotional health and wellbeing offer, which will provide a single point of access to support.

Figure 16: Map showing local areas in Liverpool and Wirral with areas shaded according to rates of planned mental health contacts and emergency hospital admissions for children and young people up to the age of 25 years

Source: NDL Liverpool and Wirral analysis of CAMHS and SUS data.

Improving data quality and completeness in Leeds

Working with a local extract of the MHSDS, the NDL team in Leeds discovered that several poorly populated data items related to protected characteristics. Improving the data quality of these characteristics in mental health datasets has also been identified as a priority by NHS Digital.

To understand the underlying reasons and develop strategies to improve the quality of these data at a local level, the team engaged directly with a mental health provider offering therapy and wellbeing services to young people in Leeds. This provider had previously rolled out an electronic patient record system, trained staff and built reusable templates for data entry. While this had led to improvements, some data quality issues remained, particularly around the recording of diagnoses and wider social circumstances of young patients. Engagement with the provider uncovered complex root causes explaining why these may be under-recorded:

- Practitioners may be reluctant to record mental health diagnoses for children and young people due to concerns about associated stigma.

- There is a lack of a standardised approach for recording self-identified gender, especially in cases where it does not match GP records.

- Parental responsibilities or young carer status may go unreported if young patients are reluctant to declare their status to teachers or the council, out of fear it may disrupt their schooling or family life.

- Information on whether children are looked after or have a protection plan is not always recorded at referral unless directly relevant to their care.

- Much of this information is recorded in patient records in free text, which does not form part of national data collections. Although it is possible to make changes to the local electronic patient record system to collect some of this information in a more structured way, the associated financial cost means only limited changes can be made in practice.

Consequently, young people with complex needs are seen by multiple services that may or may not share all relevant information with each other. It also limits the ability of local analysts to provide meaningful new insights to local decision makers, commissioners and service providers. Existing working relationships and trust have enabled the NDL team in Leeds to work with providers to develop strategies to improve data that can be adopted by other providers in their local area. This will initially focus on a subset of highly relevant variables needed to answer the most urgent questions.

Summary and implications

These analyses from teams across England, Wales and Scotland show it is possible to use local, linked data sources to gain a much more complete picture of who is using services for mental health problems. In North West London, the analysis showed a steep increase in the use of general practice and specialist mental health services. The NDL team in Grampian found increases in the percentage of children and young people receiving prescriptions for mental health problems. They also showed how the patterns of prescribing vary between girls and boys in different age groups (from being dominated by medications for ADHD for boys in the younger age groups to predominantly antidepressants for young adults, particularly young women aged 19–25). Adolescent girls and young women were also found to have the greatest number of contacts with specialist mental health services in Leeds as well as in Liverpool and Wirral, and were the group who most frequently required acute crisis care in Wales.

A persistent theme is the greater likelihood of children and young people from more deprived areas being in contact with primary, specialist mental health or crisis NHS services than those from less deprived areas. Some of these differences are stark. Crisis referrals in Leeds were 60% higher among CAMHS users in the most deprived areas than in the least deprived. Meanwhile there was twice the rate of prescriptions in Grampian and close to twice the rate of crisis events in Wales between the most and least deprived areas.

Limitations

The analyses have limitations. Firstly, the extent to which they can be generalised beyond local areas will vary. Other research suggests that some of the trends we observed are likely to exist in other areas as well, especially the rise in mental illness among adolescent girls and overall rising demand for support. But without comparable national-level data, caution must be exercised in drawing out implications for policy and practice.

A second limitation relates to the data sources, which were primarily routinely collected administrative data from NHS services. No data were available on services accessed outside the NHS that often represent a significant part of mental health support, including in schools, or services funded by local government or the voluntary sector. Data are also lacking on the use of privately funded mental health services, which anecdotal evidence suggests has risen as NHS services have struggled.

This is linked to the third limitation: the fact that these data only capture those who sought and successfully gained access to services. While some of the patterns we found suggest potentially high and rising levels of unmet need, for example falling contacts when young people transition from children to adult services, the data did not allow us to directly quantify unmet need.

Finally, most of the data used are routinely collected administrative data. These data often lack detailed clinical information, do not offer insights into how the severity and acuity of cases has changed (except for crises) and cannot shed light on the outcomes or experiences of care.

Implications for policy and practice

Our results suggest more resources need to be targeted at prevention among those most at risk of developing mental ill health.

Accepting the limitation about generalisability already set out, there were some similarities in the results across all five teams that raise questions for the future development of children and young people’s mental health policy. The high burden of mental ill health being experienced by adolescent girls and young women is a cause for concern, as is the much higher toll that mental illness is taking on those from more deprived areas. While governments from all three nations have committed to expand preventative services, particularly outside the NHS, these results suggest resources need to be more deliberately targeted at those most at risk of future problems.

Linked data sources and data sharing across sector and organisational boundaries are vital to improve services.

Any major shifts in policy should, however, be based on the best available data, including insights about those children and young people who are not getting access to services. At a national level, to take England as an example, there are still major data gaps. The Chief Medical Officer for England, the Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Taskforce and the Health and Social Care Committee have all flagged gaps in nationally available data on children and young people’s mental health, on service provision, and on experiences and outcomes.,, Nevertheless, in the absence of more complete national data, the experience of producing these local analyses from the NDL across the UK, suggests progress is possible using local, linked datasets.

For example, the research in Wales demonstrates how much more can be understood about the scale, location and consequences of mental health crises being experienced by young people than would have been possible by looking at hospital or emergency services data separately. The insights from Wales on higher rates of crisis incidents in more deprived areas mirrors the work done in Liverpool and Wirral, where a comparison of access to specialist mental health services alongside emergency admissions suggests that in some deprived areas, services may not be reaching some children and young people.

In England, the planning and delivery of services are shifting to new integrated care systems (ICSs), which are closer to the integrated models that already exist in Scotland and Wales. The local analyses shown in this briefing illustrate the potential for data-driven population health management that will be at the core of ICSs. It also illustrates the potential uses. In Grampian, for example, the NDL team linked the data on prescribing and access to CAMHS. The team found that while prescribing and referrals went up, acceptances to CAMHS treatment remained the same, resulting in a bottleneck that may have been creating unmet need among younger children, now being addressed by CAMHS.

More national action is needed to improve the data quality for NHS mental health services and data coverage for mental health support provided outside the NHS.

Local data analysis has considerable potential, but national action is still needed to make it feasible. This includes improving the data quality and completeness for NHS mental health services. Several NDL teams reported that CAMHS data quality was poor, with duplicated or incomplete data and a lack of clinical information (eg related to the presenting complaint). Data were also poor for adult services. This prevents national policymakers and local areas from obtaining reliable measures on some of the most critical and challenging pathways, including transition from CAMHS to AMHS. Age thresholds also vary by region but there is no reliable data-driven evidence on the success of local systems at managing transitions and how they have done it. Detail on other key personal and demographic information also needs to be much more complete, including ethnicity and sexual orientation.

There is also a significant blind spot about support outside NHS specialist mental health services. While specialist mental health services are under pressure, it is vital that those planning and designing services understand what happens to the children and young people turned away from specialist services. This includes whether they are able to access alternative services or other forms of support outside the NHS, or whether they deteriorate to the point of needing more intensive care.

If the findings from North West London are typical of other regions, then general practice is providing an increasingly large share of mental health services, particularly to young people, and will need increased support to do so. GPs report a number of barriers in supporting children and young people with mental health problems, including lack of time, knowledge, access to mental health providers, and resources. Other research suggests that GPs can find it challenging because of a lack of emphasis on mental health in their medical training, lack of clinical experience around young people who present with complex difficulties, or in managing transition to adult mental health services, as well as a lack of tools and resources.,,

A 2021 survey by YoungMinds of young people aged 16–25 in the UK found that although the majority had a positive experience of receiving support from their GP, 2 out of 3 would prefer to be able to access mental health support without going to see their GP. General practice is only one strand of tier 1 mental health services. Other forms of non-NHS community and school-based mental health services are being developed in all three countries, but data are either not available or not linked up with other datasets. National support is required to explore how a more complete dataset for children and young people’s mental health services can be created in all three countries – reliable enough to inform national oversight of who is using which services, and available for analysis at a local level.

More regular collection and publication of robust prevalence data, including for Scotland and Wales, would allow services to be expanded in line with need and realistic targets to be set.

As well as more frequent prevalence surveys, national bodies should also explore the feasibility of collecting more detailed data on groups likely to be at highest risk of mental illness, or most disadvantaged from accessing services. The NDL analysis found clear variation in use of services by socioeconomic group, but without corresponding estimates of need it is not possible to say whether services are being accessed equitably, relative to underlying need.

An investigation of local inequalities in access for children and young people in the West Midlands drew on qualitative evidence, suggesting that children from more deprived areas were less likely to have parental support in navigating services and faced additional barriers including the cost of transport to appointments. Evidence of equitable access to services might, therefore, need to see an even steeper gradient in the patterns of service use.

Conclusion

The scale of the challenge facing children and young people’s mental health services has been recognised by governments in all three countries. Policies are in place to expand services and support in the NHS, schools and the community, but services are not being expanded fast enough to meet the rising levels of need among children and young people. The analysis presented in this briefing illustrates how crucial high-quality data and analytics will be to understand where services need to expand in order to meet needs and reduce inequalities. This will be essential to targeting preventative interventions, planning services and improving children and young people’s mental health.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the public who took the time to review this briefing and helped to improve this work: Bārbala Ostrovska, Rain Ashley Preece, Arif Hoque and Rachael Campey. Thanks go to the public advisers who supported NDL partners with communication and engagement with the public: Aberdeen Centre for Health Data Science (ACHDS) PPIE Group, Saiqa Ahmed, Rachael Campey, Digital Services for Patients (Welsh partner), Leeds CCG Children and Young People Mental Health Task and Finish Group, Helen McGlinchey, Patricia McKinney, Hina Qureshi, Patients and Public Assurance Group (Welsh partner), Swansea University Population Data Science Consumer Panel. We would like to thank Sean Agass, Chris Carr, Andy Bell (Centre for Mental Health) and Jennifer Dixon for their contributions and comments on earlier drafts of the briefing, as well as Jay Hughes for reviewing our analysis code. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of its care and support.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2022-NDL1

Contributions

NDL Grampian: The Aberdeen Centre for Health Data Science (ACHDS), which includes NHS Grampian and t

William P Ball, University of Aberdeen

Helen Rowlands, University of Aberdeen

Corri Black, University of Aberdeen, NHS Grampian

Shantini Paranjothy, University of Aberdeen, NHS Grampian

Katie Wilde, University of Aberdeen

Katherine O’Sullivan, University of Aberdeen

Joanne Lumsden, University of Aberdeen

Magdalena Rzewuska, University of Aberdeen

Sharon Gordon, University of Aberdeen

David Ritchie, NHS Grampian

Elaine Thompson, NHS Grampian

Adelene Rasalam, NHS Grampian.

NDL North West London:

Alex Bottle, Imperial College London

Matthew Chisambi, Imperial College Health Partners

Roberto Fernandez Crespo, Imperial College London Institute of Global Health Innovation

Evgeny Galimov, Imperial College Health Partners

Sarah Houston, Imperial College Health Partners

Natalie Hudson, Imperial College Health Partners

Jacqueline Legge, North West London Health and Care Partnership

Melanie Leis, Imperial College London Institute of Global Health Innovation

Clare McCrudden, Imperial College London Institute of Global Health Innovation

Gulam Muktadir, Imperial College Health Partners

Sadie Myhill, Imperial College Health Partners

Sandeep Prashar, Imperial College Health Partners

Sara Sekelj, Imperial College Health Partners

Emma Sharpe-Jones, Imperial College Health Partners

Tomasz Szymanski, Imperial College Health Partners

Lewis Thomas, Imperial College Health Partners.

NDL Liverpool and Wirral: Liverpool CCG and Healthy Wirral Partnership

Ben Barr, University of Liverpool

Tim Caine, NHS Liverpool CCG

Pete Dixon, University of Liverpool

Matt Gilmore, NHS Wirral CCG

Annmarie Jacques, NHS Liverpool CCG

Karen Jones, NHS Liverpool CCG

Lee Kirkham, NHS Wirral CCG

Beverley Murray, Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council

Jamie O’Brien, University of Liverpool

Dimitris Tsintzos, NHS Wirral CCG.

NDL Wales: Public Health Wales, Population Data Science Swansea University, SAIL Databank, Digital H

Alisha Davies, Public Health Wales

Karen Hodgson, Public Health Wales

David Florentin, Public Health Wales

Laura Bentley, Public Health Wales

Bethan Carter, Public Health Wales

Jiao Song, Public Health Wales

Ashley Akbari, Swansea Uni

Claire Newman, Swansea Uni

Ann John, Swansea Uni

Gareth John, Digital Health and Care Wales

Joanna Dundon Digital Health and Care Wales

Lisa Trigg Social Care Wales

Owen Davies, Social Care Wales

Stephen Clarke, Welsh Ambulance Service Trust.

NDL Leeds: Leeds CCG and Leeds City Council

Helen Butters, NHS Leeds CCG

Alex Brownrigg, NHS Leeds CCG

Souheila Fox, NHS Leeds CCG

Alison Phiri, NHS Leeds CCG

Frank Wood, Leeds City Council.

References

- House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee. Children and young people’s mental health – Eighth report of session 2021–22 report; 2021 (https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8153/documents/83622/default/).

- Ward JL, Hargreaves D, Turner S, Viner RM. Change in burden of disease in UK children and young people (0–24 years) over the past 20 years and estimation of potential burden in 2040: analysis using Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data. medRxiv; 2021 (www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.20.21252130v1).

- NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan; 2019. (https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/).

- Welsh government. Together for Mental Health: A Strategy for Mental Health and Wellbeing in Wales; 2012 (https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-03/together-for-mental-health-a-strategy-for-mental-health-and-wellbeing-in-wales.pdf).

- Scottish government. Mental health strategy: 2017–2027; 2017 (www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2017/03/mental-health-strategy-2017-2027/documents/00516047-pdf/00516047-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00516047.pdf?forceDownload=true).

- National Assembly for Wales Children, Young People and Education Committee. Mind over matter: A report on the step change needed in emotional and mental health support for children and young people in Wales; 2018 (https://senedd.wales/laid documents/cr-ld11522/cr-ld11522-e.pdf).

- Audit Scotland. Children and young people’s mental health; 2018 (www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/uploads/docs/report/2018/nr_180913_mental_health.pdf).

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance report – 4. Children and young people; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report/7-children-and-young-people).

- Peytrignet S, Marszalek K, Grimm F, Thorlby R, Wagstaff T. Children and young people’s mental health: COVID-19 and the road ahead. The Health Foundation; 2022 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/children-and-young-people-s-mental-health).

- O’Shea N, McHayle Z. Time for action: Investing in comprehensive mental health support for children and young people. Centre for Mental Health; 2021 (https://cypmhc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CentreforMH_TimeForAction.pdf).

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364 (doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c).

- Meltzer H, Gatward R, Corbin T, Goodman R, Ford T. Persistence, onset, risk factors and outcomes of childhood mental disorders. ONS; 2003 (www.dawba.info/abstracts/B-CAMHS99+3_followup_report.pdf).

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists. Public Mental Health Implementation Centre; 2022 (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/public-mental-health-implementation-centre#:~:text=The%20College%20has%20launched%20the,promote%20mental%20wellbeing%20and%20resilience).

- McDaid D, Park AL. The economic case for investing in the prevention of mental health conditions in the UK. Mental Health Foundation; 2022 (www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/MHF_Investing_In_Prevention_FULLReport_FINAL.pdf).

- Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. ONS and Palgrave Macmillan; 2005 (https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub06xxx/pub06116/ment-heal-chil-youn-peop-gb-2004-rep1.pdf).

- Sadler K, Vizard T, Ford T, Goodman A, Goodman R, McManus S. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017. NHS Digital; 2018 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017).

- Vizard T, Sadler K, Ford T, et al. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020. NHS Digital; 2020 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2020-wave-1-follow-up).

- NHS Digital. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2021; 2021 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2021-follow-up-to-the-2017-survey).

- Patalay P, Gage SH. Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: A population cohort comparison study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(5):1650–1664 (doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz006).

- Angel L, Anthony R, Buckley K, et al. Student Health and Wellbeing in Wales: Key findings from the 2021 School Health Research Network Primary School Student Health and Wellbeing Survey; 2021 (www.shrn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/PriSHRN-Key-Findings-Summary-1.pdf).

- Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–892 (doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4).

- McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological Distress and Loneliness Reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(1):93–94 (doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740).

- Public Health Wales. Children and young people’s mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic; 2021 (https://phw.nhs.wales/publications/publications1/children-and-young-peoples-mental-well-being-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-report/).

- Bains S, Gutman LM. Mental Health in Ethnic Minority Populations in the UK: Developmental Trajectories from Early Childhood to Mid Adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(11):2151–2165 (doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01481-5).

- Dogra N, Singh SP, Svirydzenka N, Vostanis P. Mental health problems in children and young people from minority ethnic groups: The need for targeted research. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(4):265–267 (doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.100982).

- Patalay P, Fitzsimons E. Mental ill-health at age 17 in the UK: Prevalence of and inequalities in psychological distress, self-harm and attempted suicide. Centre for Longitudinal Studies; 2020 (https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Mental-ill-health-at-age-17-–-CLS-briefing-paper-–-website.pdf).

- Edbrooke-Childs J, Patalay P. Ethnic Differences in Referral Routes to Youth Mental Health Services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(3):368-375.e1 (doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.906).

- Edbrooke-Childs J, Newman R, Fleming I, Deighton J, Wolpert M. The association between ethnicity and care pathway for children with emotional problems in routinely collected child and adolescent mental health services data. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25:539–546 (doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0767-4).

- Irish M, Solmi F, Mars B, et al. Depression and self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood in sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals in the UK: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2019;3(2):91–98 (doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30343–2).

- Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31 (doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026).

- McDaid S, Kousoulis A. Tackling social inequalities to reduce mental health problems: How everyone can flourish equally. Mental Health Foundation; 2020 (www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/tackling-social-inequalities-reduce-mental-health-problems).

- Gutman LM, Joshi H, Parsonage M, Schoon I. Children of the new century: Mental health findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Published online 2012 www.researchgate.net/publication/308083993_Children_of_the_new_century_mental_health_findings_from_the_Millennium_Cohort_Study

- Murphy R. SPICe Briefing: Child and Adolescent Mental Health - Legislation and Policy; 2016 (www.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S5/SB_16-75_Child_and_Adolescent_Mental_Health_Legislation_and_Policy.pdf).

- Scottish Government. Rejected referrals Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS); 2018 (www.gov.scot/publications/rejected-referrals-child-adolescent-mental-health-services-camhs-qualitative-quantitative).

- Scottish Government. Children & Young People’s Mental Health Task Force Recommendations; 2019 (www.gov.scot/publications/children-young-peoples-mental-health-task-force-recommendations/documents/).

- Scottish Government. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS): NHS Scotland National Service Specification; 2020 (www.gov.scot/publications/child-adolescent-mental-health-services-camhs-nhs-scotland-national-service-specification/documents/).

- Scottish Government. A fairer, greener Scotland: Programme for Government 2021–22; 2021 (www.gov.scot/publications/fairer-greener-scotland-programme-government-2021-22/documents/).

- Audit Scotland. Blog: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Published 2021. (www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/publications/blog-child-and-adolescent-mental-health-services).

- Powis S. Clinically-led Review of NHS Access Standards Progress Report from the NHS National Medical Director; 2019 (www.england.nhs.uk/publication/clinical-review-nhs-access-standards/).