Acknowledgements

This report is based on:

Independent Evaluation of the Flow Coaching Academy Programme

RAND Europe, Final Report, August 2019. Where quotes in this report are credited as evaluation interview or evaluation report, these refer to the RAND Europe evaluation report.

Authors: Miriam Broeks, Eleftheria Iakovidou, Jack Pollard, Rachael Finn, Sarah Ball, Joanna Hofman and Tom Ling.

Interviews

The RAND Europe evaluation findings were supplemented and brought up to date by a series of interviews with the programme leads at the Central Flow Coaching Academy (FCA) and with leads from several local FCAs. Many thanks to all the interviewees who found time to contribute at the point when services were responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviewees were open and frank in their discussion of the programme, providing insights from experience to date and thoughts for future development of the FCA.

Tom Downes FCA Clinical Lead

Nick Miller FCA Programme Manager

Richard Curless FCA Northumbria

Ailsa Brotherton FCA Lancashire

Catherine McDonnell FCA Northern Ireland

Athinyaa Thiraviaraj FCA Northern Ireland

Simon Dallas FCA Devon

Anna Burhouse RUBIS.Qi

Thanks to:

Central FCA Team: We would like to thank the Central FCA for their valuable comments and suggestions on this learning report.

Steve Harrison, FCA Strategic Lead

Tom Downes, FCA Clinical Lead

Nick Miller, FCA Programme Manager

Jen Draper, National FCA Communications Manager

When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2020-I04

Preface

The Health Foundation has been supporting efforts to improve the flow of patients along care pathways for more than 10 years. What began with the Flow Cost Quality programme, to improve flow along the urgent and emergency care pathway in two acute NHS trusts, has culminated in a UK-wide programme, the Flow Coaching Academy (FCA). We have learned a great deal in the intervening years about what it takes to improve flow across multiple services and organisations, and how to sustain improvement. Our investment in programmes to improve flow has also highlighted the crucial role that good flow plays in improving patients’ care experiences and reducing delays and interruptions to their care. This is underlined in key national strategies such as the NHS long term plan in England.

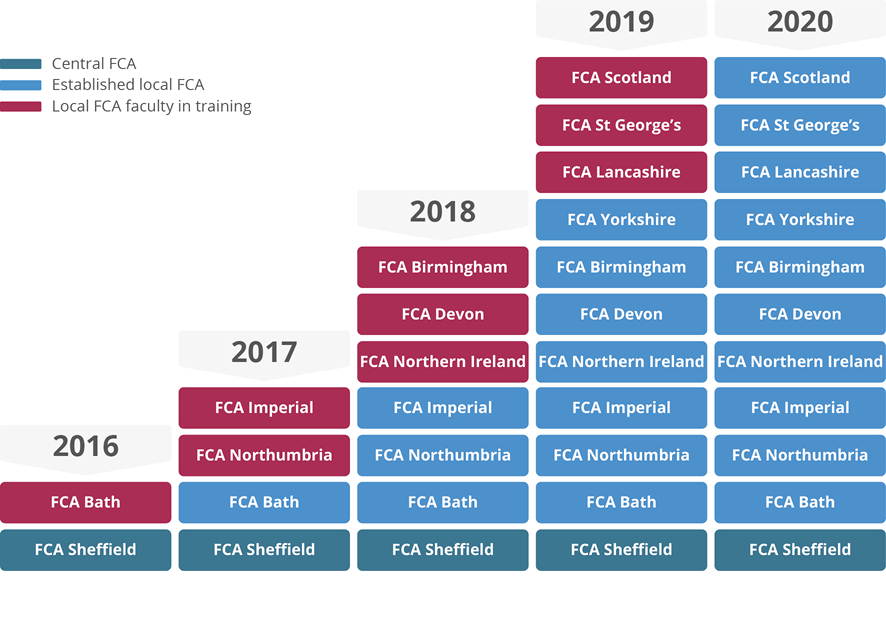

Today, most health and care systems across the UK are grappling not just with the challenge of how to improve flow along existing care pathways, but with how to design new pathways required as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. As such, we believe that system leaders, improvement practitioners and policymakers have much to gain from learning about the FCA’s experience in the first 5 years of the programme. During this time 10 local FCAs have been set up, with three more ready to start, and nearly 400 flow coaches have been trained from 30 UK health and care providers. These coaches work with over 150 multi-professional teams to improve care pathways. Some of these teams have already delivered impressive results, as the case studies in this report highlight.

What has been particularly striking has been the way that the FCA programme as a whole, including flow coaches and pathway teams, has responded to the challenges posed by COVID-19. As well as switching to virtual team meetings and enabling coaches and participants to connect and learn online, many flow coaches have been at the forefront of their organisations’ efforts to adapt and redesign services in light of COVID-19. Their training and experience in leading and facilitating care pathway improvement has proven to be invaluable throughout the pandemic.

This report, which is based on the formative FCA evaluation completed in 2019 by RAND Europe and interviews with FCA programme leads during the COVID-19 pandemic, focuses on how the programme has been planned, designed and implemented. It looks at:

- how local flow coaching academies have been set up

- how coaches have been selected and trained

- how care pathways have been chosen

- how pathway teams have approached planning and delivering improvement.

We believe that this learning will be of real value to the national and regional organisations, system leaders and improvement practitioners involved in commissioning, planning and delivering improvement programmes in the NHS.

What stands out about the FCA programme is its emphasis on the value of fostering an environment that is conducive to improvement. It is founded on the belief that to get the best from people, it is vital to create an open, inclusive, non-hierarchical learning culture in which everyone can contribute. The Big Room approach, a cornerstone of the FCA programme, is designed to achieve this. Supported by flow coaches, teams of people working in each part of the pathway come together at the same time each week in the Big Room to work collaboratively and develop a shared purpose to identify and test solutions to flow constraints. Crucially, the teams are encouraged to discover their own solution, rather than pick one developed elsewhere, helping to make sure there is local ownership of continuous improvement, and therefore increase the likelihood of it being sustained.

Another key lesson to emerge from the FCA programme is the importance of the FCAs being aligned with the overarching improvement strategy of their organisation and complementing other improvement initiatives. An example of this is FCA Lancashire, at the heart of Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust’s improvement strategy. As well as helping to avoid duplication, this alignment means the FCA has the backing of the trust’s leadership and is recognised and supported at each level of the organisation, which is critical for the long-term success of the academy.

A significant achievement of the FCA programme has been to understand and act on the lessons from previous efforts to improve flow along complex pathways across multiple services and care settings. Much flow-related improvement has stumbled at this point, with teams struggling to overcome the cultural differences and tensions that have emerged between services, so that they can begin to discuss pathway improvements. The FCA method that, at its heart, is all about relationship building and recognising that improvement happens gradually, supported by regular meetings that encourage a sense of shared purpose, offers a way of overcoming these challenges.

With 5 years’ experience to draw on, there is good reason to be optimistic about the future of the FCA programme and to share what has been learned to date. We will be releasing further updates on the roll out of the programme and the impact it is having on care pathways across the UK. In doing so, we will draw on the findings of a summative evaluation that we have commissioned from Ipsos MORI in partnership with The Strategy Unit. This evaluation, which is due to report towards the end of 2021, will give evidence of the overall impact of the FCA programme during its first 5 years of operation.

Executive summary

What is the FCA programme and its rationale?

Over the past 10 years the Health Foundation has supported the testing, development and evaluation of approaches to improving patient flow along care pathways. The most ambitious application of the approach is the FCA programme led by the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, which aims to build a network of local FCAs across the UK that share a common purpose, language and method for improvement. The programme trains health and care staff in the team coaching, technical and relationship skills required to deliver continuous and sustainable improvement. It has a core programme team, the Central FCA, which is responsible for developing the content and approach for the FCA programme and overseeing the formation of local FCAs. The rationale for the programme is that patients typically experience care in condition-based pathways, and how they move along these pathways has considerable implications for patient experience, care outcomes and pressure on staff.

What are the key components of the FCA programme?

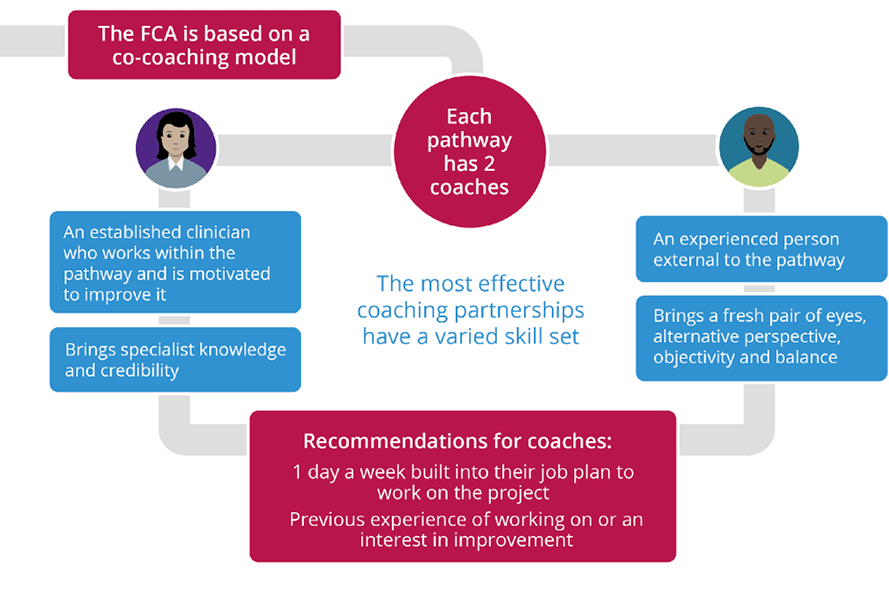

The FCA programme is based on a co-coaching model combined with elements of improvement science. Cohorts of 30 paired flow coaches are trained on a 1-year course. Coaching pairs comprise a clinical coach, who works in the pathway, and a flow coach whose day-to-day job role in the organisation is external to the pathway. The course curriculum has been successfully transferred for delivery by local FCAs and continues to be improved through iterative co-design with the FCA faculty. The paired coaches put their skills into practice while training, by jointly leading weekly Big Room meetings that bring together staff along the care pathway, enabling them to focus on the patient experience and assess, diagnose and iteratively test changes to improve patient flow. The views and experience of patients are central to the FCA model, with coaches using a range of skills and techniques to support meaningful input from patients in the improvement work. The Big Room meetings seek to make sure that each person in the room has a voice and is an equal partner in the improvement process, regardless of status or experience. This approach to flattening hierarchy, and the focus on jointly developing change ideas rather than imposing a predetermined solution, is unusual in health care improvement.

Who is involved in the FCA programme?

The aim of the FCA programme is to support the establishment of multiple FCAs across the UK, to scale up the approach and to build a networked community of practice to share learning. The local FCAs train further flow coaches in their organisation and surrounding area, and coordinate and support the work of local flow coaching pathway teams. In its first 5 years, the programme has scaled up to create a UK network of 10 local FCAs running flow improvements for a range of care pathways, with another three ready to start. Nearly 400 coaches, from over 30 NHS trusts and health boards, covering hospital, community and mental health services are trained and over 150 Big Rooms have been set up for over 85 care pathways, with several FCAs working on the same pathways, such as frailty, sepsis, cancer and diabetes.

What does the flow coaching training involve?

Flow coaches report consistently high levels of satisfaction with their training and almost unanimously feel well prepared to be a flow coach. The course includes:

- technical quality improvement (QI) methods

- measurement through statistical process control (SPC) charts

- coaching skills, such as active listening

- giving and receiving feedback

- facilitation methods

- time management.

An outstanding feature of the FCA programme has been the ability of the flow coaches to put the learning into practice by setting up Big Rooms to support continuous improvement across a range of care pathways, and sustaining this beyond the course.

Where has the flow coaching approach been applied?

A great strength of the FCA programme is the applicability of the approach across multiple clinical settings and sectors.

Flow pathway teams have reported reductions in waiting times from referral to appointment, less waiting time in clinics, reduced delays in discharge and a reduction in unnecessary procedures through the introduction of multi-professional assessments. They have also delivered better communication along the pathway and improved team culture. In addition, the emphasis on putting the patient at the centre makes sure that improvement is focused on issues that are important to patients, with greater understanding of the patients’ experience of the service. The programme effectively achieves QI where disruption of patient flow is responsible for poor patient experience, poor outcomes or inefficient use of resources.

The programme has also demonstrated its value in enabling services to adapt in response to COVID-19, which has required the development of new care pathways and improvements in the efficiency of existing pathways to tackle the waiting lists that have grown due to re-deployment of resources for COVID-19 care. Although flow pathway teams have helped to keep pathways running during COVID-19, many flow coaches have used their skills effectively to support wider organisational efforts to restart and redesign services after the first wave.

Key learnings

Developing and implementing a curriculum for flow coaches

In devising the flow coaching curriculum, the Central FCA team aimed to create a course that gives sufficient weight to the relational skills needed to drive improvement. It also allows participants to put their skills into practice and can be refined over time in response to learning.

Creating a curriculum that reflects the fact that improvement requires both technical and relational skills is essential. As well as focusing on technical skills, such as how to create process maps and use plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycles, the coaching curriculum teaches relational skills, such as how to give feedback and facilitate discussions and how to listen effectively.

Treating the curriculum as a living document is important. Developing and designing the course iteratively in response to learning and feedback helps to make sure the curriculum and training materials remain fit for purpose for both coaches and local FCAs.

Providing training participants with the opportunity to put their knowledge into practice is key to recruiting and motivating participants. The impact of many improvement training programmes is constrained by a failure to offer trainees the chance to implement their learning. This programme allows participants, while they are still being trained, to coach flow pathway teams and work with them to design, deliver and embed improvements across the care pathway.

Training multiple coaches in one organisation, each of whom goes on to coach a flow pathway team allows a critical mass of improvement expertise to emerge and increases the chances of the programme delivering a tangible impact on care. A compelling feature of the FCA programme is that it creates a network of people in an organisation with experience of coaching and delivering flow improvement. These individuals can support and challenge each other and influence others.

Ensuring that the people delivering the coaching curriculum have themselves completed the course builds participants’ confidence in the training. Creating a faculty of experienced trainers who can pass on their own experience of completing the training and coaching flow pathway teams is a key strength of the training programme in the eyes of participants. It has also helped the programme to spread.

Enabling training participants to learn with people from other organisations broadens their knowledge and understanding. Bringing together people from multiple organisations allows fresh insights and ideas to emerge and encourages people to think critically about established ways of working in their own organisations. Regular programme-wide events have also helped to strengthen inter-organisational connections and promote the exchange of knowledge and ideas.

Ensuring flow coaches have the permission, time and support to complete their training and facilitate Big Rooms is key to embedding local FCAs. Coaches’ participation in the programme often relies on them being able to secure back-fill to cover their posts while in training or to make sure they have protected time to facilitate Big Rooms. Having supportive managers and sufficient resources to allow coaches to take time away from their day job is essential.

Selecting local FCAs

When selecting local FCAs, the Central FCA team focuses on identifying flow-ready organisations with an established improvement strategy and a clear sense of the role that their local FCA would play in it.

Identifying flow-ready organisations where there is a deep commitment to improvement at every level, from the board downwards, is critical. Organisations with a clear, organisation-wide approach to improvement, with senior leaders and managers at all levels committed to improvement and a well-resourced approach to improvement capability building, are best placed to host a local FCA.

Ensuring that organisations have a clear understanding of how flow coaching fits into its existing improvement capability building strategy is vital. Organisations looking to host an FCA need to be able to articulate how flow coaching will add value to their existing improvement capability building offers and other key strategies. These organisations should also have a clear idea of where and how flow coaching will be used to drive improvement, and to make sure it is aligned with and complementary to the other improvement approaches used in the organisation.

Selecting care pathways for improvement

In selecting care pathways for improvement, local FCAs are encouraged to take their time and focus on identifying stable pathways where there are clear care challenges that are amenable to improvement, as well as engaged senior clinical leaders.

Taking time to make the right choice is key. Spending as much time as possible getting to know each potential pathway and its wider context, and working with staff and patients at each step of the pathway to understand the scope for improvement and the risks involved, will help to make sure there is a robust and evidence-based rationale behind the selection of each pathway.

Identifying pathways that are stable, clearly demarcated and well understood is important. A key advantage of the Big Room approach is that it can be applied equally effectively in any care setting or across multiple settings. However, in choosing which pathways to improve, it is important to focus on those that are coherent and well established, and those that are not affected by structural changes that could destabilise the pathway.

Striking the right balance between ambition and pragmatism is essential. Finding pathways where there are well-recognised care challenges, which are amenable to improvement within the time and resources available, is important. The presence of senior clinical leaders keen to drive improvement is also necessary. In large, complex pathways it may be appropriate to start by focusing on one specific area and building gradually as confidence and knowledge increases.

Recognising that not every quality challenge is amenable to improvement through the flow coaching approach is important. The flow coaching approach is a versatile and flexible one, but it cannot address all quality challenges on its own. Some challenges require a range of methods and an integrated organisational or system-wide response. A strength of the flow coaching approach is that it complements other improvement approaches and can be used effectively alongside other methods.

Improving the flow of care pathways

To make sure that flow pathway teams have the best chance of delivering sustained improvement, the teams meet regularly and, supported by coaches with a range of experiences and knowledge, are encouraged to work collaboratively alongside patients in an open, honest and non-hierarchical way.

Creating an open, honest and collaborative environment for improvement in which each participant feels able to contribute fully, regardless of their experience or place in the organisational hierarchy, is vital. The Big Room approach that allows flow pathway improvement team members to ‘see together, learn together and act together’ on an equal footing, has played a crucial role in galvanising teams and helped them to stay focused over time.

Enabling staff and patients from each part of a care pathway to meet regularly is critical in building a shared understanding of the priorities for improvement and fostering a culture of improvement. In bringing teams together at the same time and place each week, the Big Room approach enables new relationships across the care pathway to develop, allows questions that have never been asked to emerge, and encourages a consensus view on where improvement is most needed. It also fosters a shared ownership across the pathway of the eventual solution to the improvement problem.

Using a co-coaching model brings a valuable blend of perspectives, experience and knowledge to flow coaching pathway teams. The co-coaching partnership between a clinician with specialist knowledge of the pathway who has credibility among professionals in the team, and a coach from outside the pathway who gives a fresh perspective and ideas, is a key strength of the programme.

Involving patients from the start as equal partners in the improvement process is essential. A key ambition of the programme is to make sure that the improvement led by flow coaching pathway teams is co-produced with patients. While patients have been closely involved in a number of Big Rooms, it is far from universal and there is an awareness that more needs to be done to make this the norm.

Finding a suitable space for flow coaching pathway teams to meet is a major challenge for some local FCAs. A shortage of available space has made it difficult for some academies to find regular homes for their Big Room meetings. Switching to virtual meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic has alleviated this pressure and made it easier for some staff and patients to participate, but it has also posed new questions, such as how to build effective virtual relationships.

Building effective relationships between local FCAs and the Central FCA

Creating balanced, reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationships between the Central and local FCAs, as well as opportunities for flow coaches across the UK to connect and share learning, is seen by the FCA programme as vital to its long-term sustainability.

Seeing local FCAs as ‘co-innovators’ has helped to make sure there is a balanced and equitable relationship between them and the central academy. As ‘learning generators’ with valuable insights about the local implementation of the programme, local FCAs are seen as having a vital role to play in the ongoing adaptation and spread of the programme. This encourages a balanced flow of ideas, advice and feedback between the local FCAs and the Central FCA and fosters a sense of parity between the programme adopters and the originator. Events such as curriculum co-design sessions help to reinforce this parity.

Knowing when and how to maintain fidelity to the core programme model and when to tailor it to local needs is vital. An effective relationship between originator and adopter relies on there being clarity on when to customise content and when to follow the core model. For example, in this programme, local FCAs have the scope to include local improvement examples and data in the curriculum to increase its relevance to local participants. However, the Central FCA also arranges regular support calls, guidance notes and on-the-ground observers to help local FCAs deliver the curriculum in a standardised way.

Developing an infrastructure to support the growing network of flow coaches is a priority. The focus of the Central FCA has shifted from developing and delivering a curriculum to finding ways for flow coaches to connect and share learning and ideas. Setting up this infrastructure is vital to the long-term sustainability of the programme.

Achieving measurable and sustained impact

A clear understanding of the time required to deliver meaningful improvement in the flow of care pathways, coupled with sufficient support and resources for flow pathway teams, is seen as critical if the FCA programme is to deliver sustained improvement in care processes and outcomes.

Recognising that it takes time to identify, plan and deliver improvement in complex care pathways is vital. The Big Room is a slow burn approach that relies on repeated tests of change and sees meaningful dialogue between stakeholders along the pathway as being key to the delivery of sustained improvement. It is not an approach that can deliver quick fixes to problems.

Accessing appropriate data and data analysis support and identifying ways of measuring impact along a complex care pathway is a challenge. As is often the case in improvement programmes in the NHS, many Big Rooms have found it difficult to secure regular input from a data analyst. Another challenge is finding a suitable mechanism, or suite of tools, capable of capturing and analysing the scale of change across multiple services that flow coaching pathway teams are delivering.

Background to the FCA

Introduction

Over the past 10 years the Health Foundation has supported the testing, development and evaluation of approaches to improving patient flow, which it defines as ‘the progressive movement of people, equipment and information through a sequence of processes… along a care pathway’. The FCA programme, led by a team based at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, is the most ambitious application of patient flow yet supported by the Health Foundation. The team built on work they originally carried out in the Flow Cost Quality programme to improve flow along the urgent and emergency care pathway, bringing this together with elements from the team coaching model and improvement science approaches.

The rationale for the programme is that patients typically experience care in condition-based pathways, and how they move along these pathways has considerable implications for patient experience, care outcomes and pressure on staff. The programme approach is to train health and care staff in the team coaching, technical and relationship skills required to deliver sustainable improvement. The programme is designed to be replicable, with both a curriculum and training materials that can easily transfer to a UK wide network of local FCAs (Figure 1).

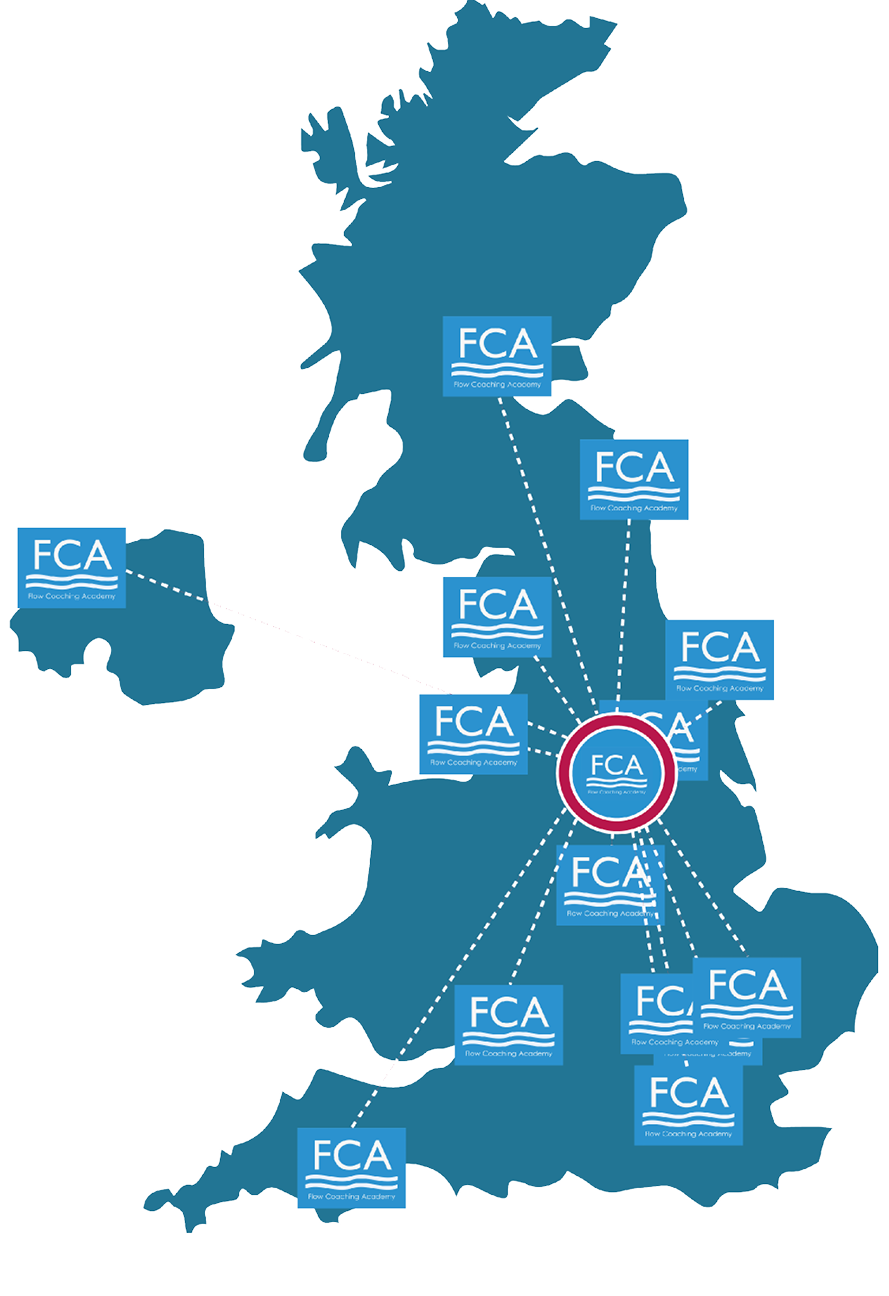

Figure 1: Growth of local FCAs through the programme cycles

Disrupted flow has implications for poorer outcomes

In common with many health systems, the NHS is facing pressures of growing demand for services and workforce shortages in a period of constrained funding and this is not keeping pace with rising costs. The Health Foundation analysis shows the number of urgent admissions to hospital has increased by 42% over the past 10 years, with patients having high morbidity and a higher prevalence of long-term conditions. Meanwhile, people living in disadvantaged areas are at greatest risk of having multiple conditions. The harmful and costly effects of delays in patient flow for older patients are well established, including higher mortality, higher risk of health care-acquired infections, depression, reductions in patients’ mobility and their ability to manage daily activities. These are recognised as major challenges in the NHS long term plan, with a number of national initiatives seeking to improve patient flow. The COVID-19 pandemic has made unprecedented demands on health and care services in the short term and continues to have an impact on the delivery of services and the need to redesign these services. In this context, improving the flow of patients, information and resources in and between health and care organisations is crucial to improving efficiency of services and the quality of care experienced by patients. Common disruptors of patient flow, such as disjointed IT and waits between stages of care, have been described in previous reports by the Health Foundation.,

Research shows that not all approaches to flow improvements in health care have resulted in measurable improvements. Beyond small case studies, some of the larger programmes have had disappointing results., Flow projects have mostly focused on a small segment of the patients’ care, due in part to the challenge of working collaboratively across multiple teams, services and organisations. A survey of US acute hospitals showed the challenge of scaling up improvement from micro and meso level to organisational level: while over 60% of respondents were using lean improvement approaches, only 12% reported this as hospital-wide implementation.

Much research focuses on process results from improvement, but the social factors contributing to improvement also need to be considered, such as encouraging and enabling supportive behaviours, team dynamics and culture. These factors help create high-performing services, sustainably achieving excellent safety and quality outcomes., A range of professions, grades, middle managers and data analysts need to be involved with a stake in the intervention. The extent to which clinical and managerial interests align is a key determinant of success in QI interventions.

Several major programmes in the NHS have focused on patient flow.

- Scotland: In 2013 NHS Scotland set up a Whole System Patient Flow improvement delivery programme.

- Wales: In Wales, 1000 Lives Improvement ran the national Patient Flow programme from 2013 to 2015 across all six health boards providing emergency care.

- England: NHS England and NHS Improvement are supporting a 5-year programme from 2016 to 2021, in which the Virginia Mason Institute – that adapted the Toyota Production System and applied it across the Virginia Mason health care system – is working with five NHS trusts to develop a culture of continuous improvement based on lean principles. The Health Foundation in partnership with NHS England and NHS Improvement has commissioned an independent evaluation of the programme, which is due to be published in 2021.

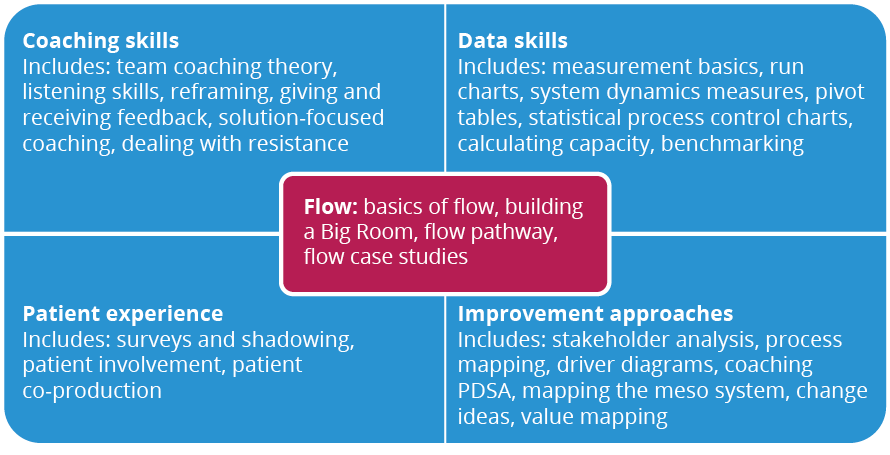

FCA coaching, technical and relationship skills

The course curriculum takes account of the idea that improvement is 80% relational and 20% technical. Expert faculty members teach flow concepts, coaching skills, data skills, patient experience and improvement approaches (Figure 2). Flow coaches also meet in smaller subgroups throughout the course, facilitated by an assigned FCA faculty member.

Figure 2: The flow coaching curriculum

A core element in the ‘flow’ part of the curriculum is the pathway assessment tool, The 5 Vs. This framework is used to assess and understand a pathway, through a focus on the following.

- Value: considering what is important for patients and families.

- Involve: how the Big Room will involve staff and patients from across the pathway.

- Evidence: the metrics that matter – data that helps to understand the system.

- Visualisation: making the evidence visual and accessible to help connect people and data.

- Vision: how the improvement work can shape the future.

The Big Room

The paired coaches support improvement on their pathway through weekly Big Room meetings (run in the same physical or virtual space at the same time each week) where health and care staff and in some cases patients, from the pathway work together to assess, diagnose and iteratively test changes to improve the flow of care. Stakeholders in pathways include all professional and support groups who have an impact on patient care and experience.

In the Big Rooms coaches aim to create an open, honest and collaborative atmosphere where each participant, regardless of seniority, feels empowered to contribute on an equal footing (Figure 3). A key principle is the flattening of traditional hierarchies and the inclusion of staff from a wide range of roles and professions. The Big Room is set up to allow participants to ‘see together, learn together and act together’.

‘Hierarchy is suspended when you go into the Big Room. It gives more junior staff or staff who have a quiet voice the chance to express their views and that’s helped everybody make progress together.’

(Infection prevention and control manager, Big Room participant)

‘There’s great enthusiasm in the room, great atmosphere and it brings together lots of disciplines in one room, with one voice, to make improvements to patient care.’

(Pharmacist, Big Room participant)

‘We kicked off our antenatal Big Room with 20 people from around the trust, setting the ground rules for how we will work together and are committed to keeping women’s voices at the heart of all we do.’

(Improvement lead, Big Room participant)

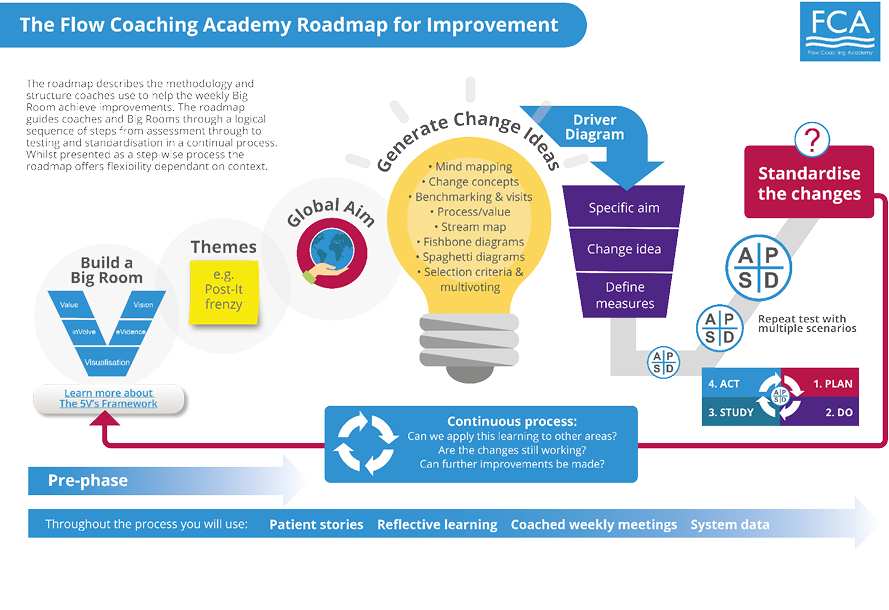

Figure 3: The Big Room approach

Flow coaches facilitate the care pathway group to share understanding about the patient experience of care, apply the techniques and methods to test out change ideas and monitor the data to evidence progress in achieving their aim. If a change leads to measured improvement, it needs to be incorporated as standard practice. The FCA roadmap for improvement offers a flexible set of steps for the pathway team to follow (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The FCA roadmap for improvement

The co-coaching model

The co-coaching model is a core element of the FCA programme. A lead clinician with detailed knowledge of the care pathway is identified as the clinical coach together with an external coach – a manager or a clinician from outside the pathway – to offer a complementary view. Coaches must be motivated to deliver improvement, with attributes necessary for team coaching. The co-coaching model brings a varied skill set into the partnership and helps build resilience into the programme, reducing the risks of unsustainability through loss of a coach (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Paired flow coaches for each care pathway

‘I am a clinician and [my co-coach] is not … having clinical and non-clinical is better because you bring different things ... [my co-coach] has a greater understanding of the operational-organisational side of the trust: pathways, CCGs, those types of things and I’ve got the clinical knowledge to back that up … if we were both clinical, it might be more difficult to engage some people that aren’t clinical.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

Recruiting and setting up local FCAs

One of the great strengths of the FCA programme is the adaptability of the approach across multiple clinical settings and sectors. The approach has been applied across community and acute pathways, such as a cross-sectoral frailty pathway and a mental health pathway spanning an accident and emergency department, police and community mental health. Initially, pathways tended to be in the acute sector, as hospital infrastructure facilitated the set up of big rooms and, in theory, access to the pathway data. With experience and the shift to virtual meetings, the pathway work is spreading across community and mental health sectors.

NHS provider organisations are invited to express interest to participate and to identify condition-based pathways where the approach can be applied for a specific condition, such as diabetes, skin cancer, frailty or a discrete area of cross-system care, such as end-of-life care or sepsis. The pathway is viewed from the patient perspective, covering different clinical departments and other health and social care providers.

The Central FCA selects organisations to host local FCAs through a rigorous application process. Selection is based on perceived readiness for the programme. The organisation must be committed to improvement, with leadership support at all levels and organisational development, improvement or transformation functions to indicate they are ‘flow ready’.

Iterative learning by the Central FCA has deepened understanding of what contributes to flow readiness, such as identification of a suite of pathways with clear rationale for their selection and initial ideas about how flow coaching might enable improvement. However, it is understood that flow coaching is not a panacea for every quality issue or organisational challenge.

‘A single methodology is unlikely to succeed across a whole trust. We look to use flow coaching when there are flow issues. We also use lean methodology as appropriate and small-scale improvement projects. A Big Room is quite an investment and not necessary for every improvement effort. It is best for tackling thornier issues, where all the stakeholders need to be involved to make improvement happen.’

(Local FCA lead)

Figure 6: The FCA network (November 2020)

Local FCAs deliver the 1-year training programme and deliver ongoing support to their local community of flow coaches. The Central FCA worked with an agency specialising in social franchising to formalise key aspects of the relationship between the Central FCA and local FCAs. Achieving the balance between fidelity to the model and necessary local adaptation is a well-documented challenge in spreading successful improvement from the originating organisation to adopter sites. Local FCA faculties customise the training, using local examples, adding local videos and including data from their Big Rooms. This helps participants understand the content in their context.

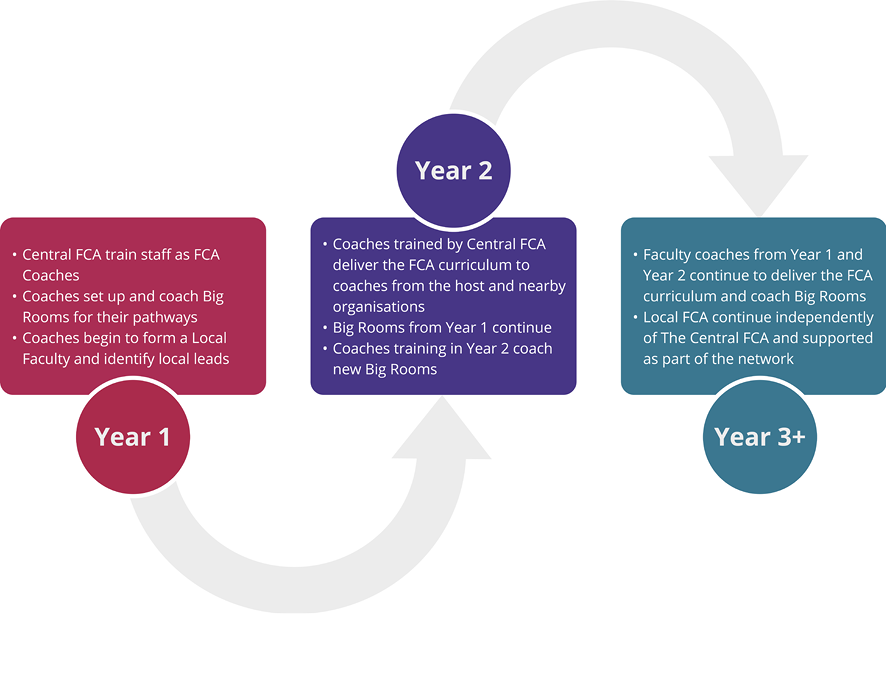

Figure 7: Overview – setting up a local FCA

A local FCA initially identifies a minimum of six coaches for three care pathways. The Central FCA recommends that at least four of these coaches should be chosen with the expectation that they will become the teaching faculty and deliver the course locally. To join the teaching faculty all coaches need to complete their training and be coaching a Big Room. Currently the faculty for local FCAs have all been trained by the Central FCA. However, there is a desire to involve local FCAs in the delivery of training once they have become more established, in order to allow greater flexibility for scheduling courses and to free up development capacity at the Central FCA.

As the local FCA faculty delivers flow coach training for the first time, the Central FCA gives advisory support, all training materials, guidance notes and regular support calls over the first year. Before COVID-19 restrictions the Central FCA was committed to providing on-site support to every session during the first year of delivery. This made sure that local FCAs were supported while providing assurance that the curriculum was being delivered as expected and new learning was brought into the network.

Due to COVID-19, the Central FCA are developing e-learning packages and digital resources so the training can be delivered remotely. This will also help reduce the need for travel to different areas across the UK and will open up opportunities to develop shared faculty models across the network.

‘We were quite nervous when we ran the first local cohort, but we had support from the Central FCA at most of the sessions and we feel we’re trusted to deliver it now. It is effectively a franchise model and it needs to ensure the same focus and content, not deviating from the curriculum … We have the script and the template, but we run it in our own personal style.’

(Local FCA lead)

Curriculum co-design sessions with Central FCA and local FCA faculty members identify areas for improvement and highlight why certain elements of the programme are crucial and how these need to be taught.

‘There is a temptation to tweak and adjust the content, especially if you don’t quite ‘get it’. The fact that the Central FCA are so available means you can have that conversation to ensure you fully understand the module before you teach it, rather than change things.’

(Local FCA lead)

The level of support that local FCAs need reduces over time as confidence grows and there is more familiarity with the materials and approach, as well as the experience of running their Big Room pathways.

‘Central FCA are amazing! They’re very supportive and share all their knowledge and materials, and the things they’re developing … It’s very different from a lot of NHS competition culture.’

(Local FCA lead)

Local FCAs can experiment with changes to the format, as long as learning is shared across the programme. One local FCA wanted to have 2-day, rather than 3-day, modules to help clinicians attend without needing formal approval for study leave. However, experience showed that attendance dropped because without the formality of requesting leave it was harder to protect the time.

Successive cohorts of trainees have been able to make better progress with their pathways due to the build-up of collective experience across the FCA programme.

‘So, I think it’s a bit about the fact that the faculty have all done the course. You can teach them to avoid some of the pitfalls that you fell into so that, each time round, the next group of coaches can avoid the pitfalls a bit more easily.’

(Local FCA faculty member, evaluation interview)

‘I’ve gained just as much from teaching the course as participating in it, after two rounds you start to see the issues through a different lens ... we’ve talked about this as a cohort of coaches on faculty now and how we’re just learning more to apply to our own pathways as we teach.’

(Local FCA faculty member, evaluation interview)

Aligning FCAs with organisational strategies for improvement

Local FCAs need to understand how the programme fits with, and can enhance the delivery of, existing organisational strategies for improvement. FCA Devon is unique to date in England as a joint application by the acute hospital trust and the mental health trust, which has enabled work on pathways extending beyond organisational boundaries. However, FCA Devon is also conscious of the need to make sure its activities are aligned with organisational priorities. For example, when a new electronic patient record (EPR) system was the focus of trust level strategic attention in FCA Devon, the flow coaches supported the digital roll out. Their heightened understanding of pathway information flows and interactions between services helped to avoid some of the common pitfalls of EPR introduction.

FCA Lancashire, meanwhile, positioned the FCA programme as an opportunity for clinical leadership development. Getting clinical leaders together in a ‘programmed’ approach has unlocked ways to solve problems that seemed intractable. The FCA programme has brought acute and community teams together, who previously did little joint working. Their frailty pathway now has a shared assessment for older people, whereas in the past each team carried out their own (different) assessment.

‘A medical engagement programme was really important to get the medics on board – you have to be realistic and devote more time and energy to that. Of course, we want nurses and other staff on board, but they are relatively easy – very keen from the outset; medics are the harder nut to crack and it’s vital to get real traction in clinical areas.’

(Local FCA lead)

In contexts where the FCA is strategically positioned in an organisation-wide approach, support and buy-in from senior leaders can facilitate progress and stability for the approach. For example, at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals, the FCA is firmly embedded into the organisation’s improvement strategy as the primary means of driving improvement at the meso level. The trust has responded to the drive from the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and NHS England and NHS Improvement for trust-level commitment and a planned approach to QI. Flow coaching is closely aligned with the overarching capability building approach for the trust and therefore more likely to sustain and develop. Selecting organisations with the right conditions to support the programme is recognised as being crucial.

‘We built our application around our strategic approach with the CEO, medical director and director of quality working together on a vision for delivery of the FCA. We realised success depended on investment in learning about flow coaching as our chosen approach and a commitment to engage with staff, particularly getting the medics on board and getting sufficient numbers trained in the approach.’

(Local FCA lead)

However, in many local FCAs flow coaching is one of several QI programmes operating across the trust and competing for executive attention and organisational resources. Nonetheless, several local FCA leads described how the FCA programme model has helped them to develop a more coherent strategy for QI capability at an organisational level.

‘Although as a trust we have a long history of improvement work and investment in clinical leadership prior to the FCA, I don’t think we had a mental model for what we were doing. This [FCA] gave us a focus for our high-level capability and capacity building, linking pathway development with service transformation ... It gives us the top tier of training to complement the half-day QI introduction session and 3-day QI Leaders’ course that we were already running.’

(Local FCA lead)

Several local FCAs also described how the flow coach training fits into a tiered model of QI training, complementing the Introduction to QI sessions and other shorter courses.

‘We recognised that starting an FCA would complement the QI training we were already doing at a less intensive level and help us get to a critical mass of QI informed, QI trained and, through a local FCA, QI leaders across the trust. But the FCA is more than capability building – it gives us a better way to use the skills of the dedicated central transformation team to support improvement owned by the clinical teams; not to run in and “do unto” the service teams.’

(Local FCA lead)

FCAs with a nationwide reach

The approach for FCA Scotland has been more nationally oriented from the outset, sitting in the NHS Education for Scotland national QI training offers. Recognising the level of existing QI skills and experience across the NHS in Scotland, the delivery pace for FCA Scotland was accelerated. In 1 year, the first cohort of Scottish flow coaches were trained and delivering training to coaches from the Scottish health boards.

FCA Northern Ireland is also working to position the programme as a national initiative. While the drive has initially come from the Western Health and Social Care Trust, the first local training cohort involved coaches from all six health and social care trusts. The logistics of where to hold course sessions has been important, running these in Belfast rather than their Londonderry base to facilitate travel across the country. The development and testing of e-learning resources (such as videos, online seminars, sub-group time and supported Workplace activity) and delivery of virtual training is currently underway and will facilitate national access. For example, FCA Northumbria, FCA Birmingham, FCA Northern Ireland, FCA Scotland and FCA Imperial have completed, or are in the process of completing, training online for their current cohorts.

Strengthening the profile and reach of FCAs

Local FCAs are encouraged to recruit and charge for flow coaching trainees from outside their organisation to increase impact and generate a local revenue stream. The available training slots have been eagerly taken up.

‘The wider clinical management team are now appreciating the power of this. We have seen the skills in action and now we want to work like this across the trust.’

(Local FCA lead)

Local FCAs are keen to develop their academies and to initiate more pathway improvement across their trusts, with a sense of urgency to rapidly train more people to the skill level of flow coaches in the wake of COVID-19.

‘We can’t wait around for a year for this to happen. Services have been deconstructed and we need to reconstruct along the pathways, not purely along existing service lines. We need FCA expertise for this and we need it more speedily than the traditional model.’

(Local FCA lead)

This challenge is being met through the development of an online modular flow coaching course, which will enable local FCAs to train more than the current total of 30 flow coaches per year, and to accelerate the delivery of the programme so it can be completed in less than a year.

Implementing flow coaching in practice

Developing and implementing a flow coaching curriculum

Flow coaches highly rate the training course

Evaluation surveys completed by the first three cohorts of flow coaches as they started the training, at 6 months into the training and at 12 months when training was completed, gave consistently high satisfaction ratings for the training. The content was found to be useful and relevant. Flow coaches, almost unanimously, believed they were well prepared for the role.

Flow coaches valued learning technical QI methods such as process mapping, using PDSA cycles and measurement through SPC charts. They also valued the suite of coaching skills, such as active listening, giving and receiving feedback and time management. Evaluators observed high levels of engagement among flow coaches in training sessions, with supportive, engaged and knowledgeable faculty.

‘The trainers … were fantastically supportive. And they really … did a great job of delivering the content in a way that was meaningful and useful and it felt, in a lot of cases, that we were all learning together and that was a really positive learning environment. It felt very safe and supportive, so commendation to the people who delivered the content, as well as those people who developed the content in the first place.’

(Flow coach trainee, evaluation report)

Different trainees rated different aspects of the course most highly. Some particularly valued the powerful patients’ stories, others were motivated by examples of flow coaching in practice. One flow coach saw the use of statistics as the least useful aspect of the flow coaching training, while others found the data skills sessions essential to develop their data analytical ability.

‘I think the balance of content between the measurement and the team development stuff is probably about right, actually. So, I would have liked more of the measurement stuff and part of the group would have probably liked much more of the touchy-feely, but that’s just the spectrum of people you’re dealing with.’

(Flow coach trainee, evaluation report)

Flow coaches gain new skills from the training

The majority of flow coaches confirmed that they were using what they had learned from the training and were seeing positive results. A few flow coaches reported major personal impact from the training.

‘I’ve done lots of training before, including intensive QI and lean, as well as some management training, but this has transformed the way I think about working with people on improvement. It’s a fantastic journey and gives a different lens and way of being collaborative.’

(Local FCA lead)

My lightbulb moment came when I realised that before it had always been about getting staff buy-in to our vision, either as service leads or the organisation’s plans … Flow coaching is about the team owning their ideas for what needs to improve … that’s what makes it long term and sustainable.’

(Local FCA lead)

Flow coaches have gained and mastered new skills, including leadership, team management, active listening, reflecting on their own work, problem solving, facilitating effective discussions, engagement and developing mutual understanding. These skills have also had wider applicability.

‘Flow coaching is helpful to look at data … to get the best out of people. So, how to not give people answers, but let people come up with their own answers. It certainly helped in terms of some difficult decisions. I think it does help in terms of some kind of … difficult conversations when you have people that aren’t in agreement with what you’re doing and just how to move forward positively.’

(Flow coach trainee, evaluation report)

Participants reported becoming more confident in using flow coaching tools throughout their work, not just in Big Room meetings.

‘I feel much more confident, [the new skills] have really helped to empower me in my daily job … regarding the knowledge about data and charts. They always come to me and say “What would you think? How would you interpret this?”.’

(Flow coach trainee, evaluation report)

Flow coaches also reported increased confidence, coaching skills, expanded professional networks and increased competence to work with data. It was felt that professional development from flow coaching generated key skills that trainees could use throughout their career.

‘There’s definitely been development for me in terms of my personal confidence in dealing with quite senior people or clinicians that, you know, might otherwise in other forums be seen as quite powerful … So, I think in terms of having influence and credibility, confidence to deal with perhaps difficult situations or challenging circumstances, these have definitely all been things that I have got out of this.’

(Flow coach trainee, evaluation report)

Flow coaches can put what they learn into practice

An outstanding feature of the FCA programme has been the ability of flow coaches to put into practice what they are learning: to set up and coach a Big Room, to make improvements on their pathway and to sustain this beyond the 12 months of the course. Only four respondents out of 50, across the first three training cycles, reported not being able to apply any of the learning in practice

This ability to apply learning is not universally achieved by QI training. Several studies have illustrated the difficulty for staff in translating QI models and theories into action., Research shows that staff trained in QI can feel isolated without additional support and unable to secure priority for QI, given the pressures of day-to-day work. The QI-trained staff also find it hard to pass on learned technical methods, such as PDSA cycles, in a way that can be implemented effectively by others.

Flow coaching brings together different elements to achieve improvement

‘What’s really good about flow coaching is the way it bundles all of the [QI techniques] together and uses coaching methodology in order to work with … large groups in a pathway to deliver that service improvement. That’s the bit that’s different.’

(Trust senior leader, evaluation interview)

‘The fact that a team is trained is vital to [FCA] success – no matter how good an individual course is, one person going back into the trust is going to struggle to make an impact. When you start with a minimum of three teams involved, it immediately multiplies the effect. Each coach has their flow coach partner to work with on their improvement and the other flow coaches to relate to in the trust.’

(Local FCA lead)

Flow coach training has created additional organisational benefits

Trust senior leads reported changes in behaviour of coaches and other staff as a result of flow coaching.

‘We know that having done this course in itself will make you a better leader and build quality improvement and systems thinking into your way of working.’

(Senior FCA lead, evaluation interview)

‘It’s one of the best QI and leadership training courses out there. I saw [flow coaches] ‘growing’ in front of my eyes: in their confidence and relationship building. The greatest legacy is having these brilliantly trained people in the trust, who are able to tackle the really thorny issues.’

(Local FCA lead)

The benefits of flow coach training have been recognised as benefiting a local FCA trust more widely during the recent emergency response to COVID-19, as the quote below and Box 1 show.

‘The people who have had the [flow coaching] training have responded rapidly to COVID-19 challenges and got changes in place very quickly. The coaches have been very visible in their leadership in the trust and working to a rhythm of developing ideas, testing it out and engaging with people as they go.’

(Local FCA lead)

Box 1: Applying flow coaching skills during COVID-19: case studies from Sheffield and Devon

Sheffield's Anaesthesia and Operating Services department during COVID-19

Karl is Clinical Director for the Anaesthesia and Operating Services department at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. In this leadership role during the pandemic, he describes his FCA coaching skills as being invaluable. At the height of the first wave he facilitated Big Room-style team huddles to flatten the hierarchy, use data objectively to inform decisions and collaborate as a team on key challenges – all fundamental aspects of FCA methodology. The collective ownership, performance and morale this engendered in his team helped the department navigate the biggest professional challenge they had faced to date.

Using flow coaching skills to manage COVID-19 supplies in Devon

At the start of the pandemic one of Devon FCA’s flow coaches was deployed to work with his trust’s stores, procurement and facilities team to help manage the organisation’s COVID-19 supplies. Using the skills developed as a coach, he facilitated daily meetings with a wide range of stakeholders with the aim of creating a collaborative working environment and highlighting the interconnectedness of the different systems in use. He is now leading the team through a series of PDSA cycles to make sure the trust has sufficient supplies during the second wave of the pandemic.

Coaches benefit from doing the course with flow coaches from other organisations, gaining fresh insights from their experience and their organisational context. The faculty from local FCAs have noticed the difference between running an internal course in the first year and then opening it up to other trusts for the second and subsequent years.

‘It’s very important to have six coaches from [neighbouring trusts] and understand their views. They can have a very different perspective; it refreshes our thinking.’

(Local FCA lead)

Identifying and setting up flow coaching pathway teams

Big Rooms facilitate engagement and relationship building

The Big Room meetings get stakeholders who are not usually in the same room to talk to each other, leading to better understanding of roles, breaking organisational barriers and facilitating collective work on problem solving.

‘The fact that two groups are talking to each other that never talked to each other before is pretty profound … community nurses are now talking to the acute hospital nurses. The fact that they’ve now got a set of skills to actually understand what their key issue is in their pathway and have started to do tests and make changes and got people ownership is quite profound.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

Gathering staff along the pathway in a Big Room builds a shared perspective. New connections and new communication channels facilitate changes to improve flow.

‘The hospital and the community worked very separately … And I think one of the great things about flow coaching is that it’s brought us all together, and so staff are communicating well with each other in a way that they hadn’t before. A lot of phone calls go backwards and forwards now in a way that they weren’t ... it’s really had a great impact on relationships between us all, to the point where we can just ring up and say, “look, you know, this has been a bit of an issue”[…] That’s one of the best things about flow.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

A key benefit of flow coaching is to flatten hierarchies, resulting in joint decision making. Flow coaches felt that changes tested by pathway teams, based on Big Room discussions, were implemented with less resistance than if they had been imposed top down.

‘Anyone can propose an idea and it’s not just entertained, it’s actively encouraged. So I think that’s a key strength of it … before my lean thinking was always based on tools, value stream mapping, PDSAs … I always read about cultural change as the most significant thing and it’s actually taken me by surprise, but I will honestly say in the last 3 months that’s really come to the fore.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

By bringing pathway staff together, flow coaching opens a space for questions that have never been asked. Staff gain a better understanding of each other’s service and the pressures they face. It facilitates co-design among multi-professional groups and helps to nurture an appetite for change, fostering a flow coaching culture. Coaches described changes in mind-set or culture as a major success of the programme.

‘I think the biggest milestone for us has been a recognition … for something to be done differently. And that there is a high level of motivation for that to happen, so people recognise that not only does something need to be done differently, but they want to be part of doing things differently. So people are motivated to make change happen and now we just need to move to that point of better understanding of what that “doing things differently” looks like and making it happen.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

Another key benefit of the Big Room approach is that it gives teams the chance to learn and reflect together.

‘Everyone in the Big Room has come out with another set of skills. Because it gives us, as a team, time for reflection, it means that it’s more likely to stick.’

(Local FCA lead)

As a result, many Big Rooms have been able to sustain the interest and enthusiasm of participants, according to flow coaches.

‘Everyone just comes along and gives up their time willingly … We can’t say how much we appreciate that and the fact that the directorate sees it as a priority too.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

‘The ‘why’ is never forgotten in the Big Room and that just shoots [the work] up into the stratosphere, staff come because they care about patient outcomes and that is always the focus.’

(Local FCA lead)

Changes in organisational culture have also been observed, resulting from Big Room engagement and flow coaching activities.

‘Interestingly I thought that we might have more of a culture of resistance to change than we have. I thought that it would be hard to change the culture and actually I think the opposite has really been the case, I think people have been embracing change.’

(Flow coach, evaluation interview)

Box 2: Benefits ascribed to flow coaching implementation by coaches and Big Room participants

- Bringing staff along the pathway together: people who do not usually work together join to focus on the care pathway in Big Room.

- Patient perspective for improvement: focus on patient stories highlights important issues for improvement.

- Flattening hierarchy: allowing any of the staff involved in the pathway to, for example, propose ideas and challenge data.

- Better communication: between different professionals, different services and between teams from different organisations.

- Improvement culture: increased willingness to try changes and do something differently.

- Brings together QI tools and coaching: supports use of the tools in practice with supportive leadership.

- Better flows of information: exchange of ideas and more accurate care information feeds into ideas for change.

- More ownership of improvement interventions: Big Room participants discuss and agree which change ideas to attempt.

- New skills brought into the pathway: presenting patients’ stories, running complete PDSA cycles on each test of change and the use of SPC charts.

Select care pathways for improvement carefully

The Central FCA has gained expertise in selecting appropriate care pathways amenable to flow coaching. Experience has shown that a successful Big Room can bring together staff from different services who support the same patients, for example, community mental health teams and accident and emergency departments supporting people in mental health crisis, or hospital and community teams working with frail, elderly people. Without the focus of a clear pathway, an early Big Room on chronic pain was not successful. The learning from this helped to shape the approach for cross-service pathways, such as sepsis. The initial sepsis Big Room tested changes in one defined area, making necessary tweaks while engaging stakeholders across the whole pathway, and ultimately gaining confidence for wider application of cross-service improvements to sepsis care.

The Central FCA has recognised the problem of selecting pathways too quickly, with insufficient analysis of the context, and advise trusts starting flow coaching on how to avoid common pitfalls. These pitfalls could include working on pathways that are unstable due to, for example, structural changes. Trusts are encouraged to select pathways with an appropriate balance between ambition, involving pathways where there are known quality of care issues and pragmatism, and selecting pathways with keen clinical leaders.

‘We opened up applications across the trust, and it was over-subscribed, so we chose two pathways to get ‘quick wins’: colorectal, as we had identified the pathway needed redesign to ‘work smarter’, and sepsis, as we were very impressed with the work at Imperial. The other pathways were frailty, where there had been intractable problems for a long time between acute and community teams, and inflammatory bowel disease, because the clinical team were just so keen to get involved.’

(Local FCA lead)

Big Rooms also need to balance their aspirations for improved patient outcomes with what is manageable and realistically achievable through QI approaches, by building up pathway level impact through a series of changes. Addressing what is manageable can lead to a micro-system focus (a small-scale QI project on a segment of the pathway, usually only involving one clinical team) rather than the desired meso-system approach, improving flow along the whole care pathway. In an example of micro-system improvement, a local FCA Big Room only focused on the discharge process for their pathway, which achieved worthwhile improvement but did not consider other parts of the pathway and therefore limited the overall impact.

Challenges in setting up and sustaining Big Rooms

Not all the Big Rooms have been successful. In a small minority of cases, slow progress led to the Big Room meetings being discontinued. For example, flow coaches reported lack of engagement from senior or middle managers to attend the Big Room as a barrier to progress. It can be hard to implement a flat hierarchy if some Big Room participants hold on to power and control, and resist new approaches.

‘Some people come but they’re like observers, they don’t share their information … We’ve also seen resistance to the new approaches we want to try ... not everyone gets that pathway idea, they’re only interested in their own area.’

(Evaluation case study)

Another challenge faced by some flow coaches has been in getting back-fill to cover the time they spend training or facilitating Big Rooms, or in earmarking protected time for their role in a formal job plan after the training.

Enacting the coaching role, such as delegating team roles and ensuring ownership in the Big Room, rather than leading and directing work, has also required a change in approach for some flow coaches. Tensions resulted from balancing an operational function in the pathway with the coaching role. Time and workload pressures made it hard to sustain the coaching role beyond the end of training (particularly for clinical coaches). Organisations need to consider the support that flow coaches need to sustain the Big Room approach.

‘We won’t have workshop days in the future, so we need to think how we can come together and support each other to keep it going. We need to actively keep skilling up, keep flow coaching with a high profile across the trust, or we’ll lose the edge we’ve gained from this fantastic experience.’

(Local FCA lead)

Some local FCAs have also found it difficult to set up Big Rooms due to a shortage of suitable spaces in NHS organisations to physically hold these meetings. Dealing with the time pressures that staff are under, when faced with a requirement for another weekly meeting, is also a concern.

‘We have to have a mobile Big Room venue due to the geographical distance between the sites involved. We’ve also had to think about how to cover participants’ travel expenses. The trust is covering these for now, but it will be a big barrier if that support doesn’t continue’.

(Local FCA lead)

‘It’s been really hard not having regular attendance [at Big Room meetings]. We have to keep going backwards to catch up on the rationale and the aims ... I know everyone’s busy, but we can’t make real progress if we don’t have the representation along the pathway.’

(Evaluation case study 1, evaluation report)

Some of these challenges have been addressed by meetings switching from in-person to virtual during the COVID-19 pandemic. The virtual format facilitates patient involvement on a more equitable basis as they can take part in their own space. It also benefits GP, community and social care attendance, as they no longer need to factor in travel time.

These benefits are balanced by virtual meetings being a harder medium to build the relational side of improvement. It is harder to hold a meaningful discussion if there has not already been a functioning face-to-face relationship. This suggests risk to the sustainability of Big Rooms set up during or post-COVID-19, which only meet virtually. The Central FCA team have learned that this can be mitigated by extra attention to relationship building with key staff, using a combination of engaging by video conference and in person (with appropriate social distancing).

The rapid shift to online consultations and meetings across the NHS in response to COVID-19 escalated work development of the training for online delivery, requiring innovative ways to facilitate connections between participants in a virtual setting. Online training has advantages in reducing the costs and time required to attend in-person training and enabling greater numbers of flow coaches to be trained, more quickly. The FCA programme can now to be delivered in-person, online or through a hybrid approach, combining the efficiencies and accessibility of virtual with the relational value of in-person training. For example, at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, the frailty Big Room moved onto the Workplace online platform in June 2020, allowing the team to connect, even when working remotely. The platform enables everyone in the group to access the online discussions and to find the posts that are most relevant and helpful for them. Documents are uploaded to a shared space where everyone can edit and comment on them directly, with no need to wait until the next meeting.

‘It’s kept me connected to things I wouldn’t usually be connected to and has more of a sense of community. It allows people to contribute straight away and there’s more visibility of the conversations that are taking place.’

(Frailty Big Room coach)

Developing an FCA network

Local FCAs are co-innovators in the FCA network

Central FCA works with the teams at local FCAs as co-innovators in developing the programme. There is a clarity that the adopters are ‘learning generators’ with as much to contribute in understanding how the programme is working and how it needs to adapt as the originators. Local FCA leads recognise the benefit of regular communication and exchange of ideas with each other and see the development of the FCA network as key to this.

‘Local faculties can exchange ideas and material and stuff, and individual Big Rooms can say, “Hey, we did this really well” or “This is what we’ve achieved” or “Anybody know how to solve this problem?” The programme will gain more momentum and coaches and faculty will gain learning and knowledge by being able to share in that way.’

(Local FCA lead, evaluation comment)

During the programme’s implementation, the focus of the Central FCA has shifted from developing and delivering the curriculum, to designing and testing the operational model to grow and maintain the FCA network as a thriving community of practice. The growing community of flow coaches need the infrastructure to support ongoing engagement, exchange of ideas and communication for the sustainability of the programme.

‘Central FCA are great at receiving and responding to feedback … these feedback loops are really important and they are absolutely in place for the programme.’

(Local FCA faculty member)

The Central FCA engages with the local faculties to enable them to give local support to their coaching community and to collaboratively develop the national FCA network. Regular network events are hosted by different local FCAs showcasing their work and this is an opportunity for all FCAs to share learning at different stages in the programme. Each local FCA is expected to hold two local faculty events annually to develop coaches. The Central FCA runs curriculum co-design days, bringing together representatives from each local FCA faculty to discuss and refine the flow coaching curriculum.

‘The curriculum day was run very much in the FCA way, breaking down the hierarchy, not Central FCA and ‘the rest’. It’s very much ‘do as they do’, not ‘do as they say’ and that builds our trust in the Central FCA team.’

(Local FCA lead)

‘It’s important to keep in learning mode through these events. It stops the local programme getting stale as we keep learning from what others are doing. The Connect event that was run virtually was great, really successful and we want to keep this going. It’s very important to get everyone together. Virtual is good for now, but it will be important to ensure in-person meetings when these are possible. This is where the deep relationship building happens.’

(Local FCA lead)

Keeping members connected as the FCA network grows

The current scale of the FCA network means that personal contacts, although still important, are insufficient as the organising force. The network is using Workplace as a dynamic online platform to facilitate sharing comments, enquiries and contacts between local FCAs and individual flow coaches. Coaches can download materials, make connections and seek support from others working on similar issues on their pathway. Flow coaches working on sepsis and frailty across local FCAs run virtual groups to facilitate rapid knowledge transfer. Coaches connect on a range of flow coaching topics, not just pathway issues, where they are facing common issues. In addition, the dedicated website has pages for each of the local FCAs to upload their case studies and successes – https://flowcoaching.academy

‘The new website is great and will really help to raise the profile of the work and help connecting with other FCAs. It builds on the Twitter stream, which is a great way to stay in touch with what’s happening in the flow-coaching world.’

(Local FCA lead)

Maximising the impact of the FCA programme

This report does not aim to examine the impact of the overall FCA programme. We will be in a better position to explore the overall impact once the findings of the summative evaluation of the programme, which has been commissioned by the Health Foundation, are known. However, some important learning points have emerged from the earlier formative evaluation regarding the steps required to enable the FCA programme to maximise its chances of delivering sustained improvements in care processes and outcomes. As well as discussing these learning points, this section includes local case studies illustrating the impact already achieved by flow coaching pathway teams. These case studies illustrate the potential contribution that the FCA programme stands to make to health and care across the UK.

Allowing time to achieve impact is vital

For many pathways, it is too soon to assess the impact on measurable outcomes immediately after the training. Flow improvements on care pathways need to be sustained beyond the first year to enable the delivery of measurable results. It also takes time for flow coaching pathway teams to identify, test and refine improvements, something that some organisations have found difficult to accept. Several interviewees described how organisations still tend to look for quick fixes for service improvement. They were confident that while the slow burn nature of the FCA intervention takes longer to deliver results, these are more likely to be sustained improvement outcomes and that the coaching relationship is what enables a sustainable improvement.

‘Flow isn’t about very quick turnaround. [It’s] repeated PDSA cycles and … a drip effect that leads to success rather than doing things in a big way very quickly. So that’s been a bit of a culture change that we’ve had to work on explaining. And it’s why it’s important to … take our time and to really understand the problem before we come up with solutions.’

(Flow coach, evaluation report)

‘You have to let the emergent work mature and keep people with you over the 2 years. After 2 years’ investment, you then start to see results. In my experience, it’s worth far more than 8 years of piecemeal QI projects with patchy results.’

(Local FCA lead)

There are challenges in measuring impact across complex care pathways

The FCA programme needs to take a broader view on how impact is measured across the programme. In many ways the pathway work is going beyond what can be measured on SPC charts in response to PDSA tests of change. When communication and cooperation improve between teams along a pathway, all sorts of profound changes in performance can happen. This reduces delays and improves coordination of care, but not in ways that can be clearly linked to a PDSA cycle.

The focus on meso-level improvement across the whole pathway compounds the difficulty, as data need to be collated and integrated from different organisations, which NHS IT systems are not well set up to do, requiring multiple data permissions from different organisations. FCA improvement work is sometimes the first attempt to collect data along the whole pathway.

The Central FCA insights and analysis workstream coordinates the collation and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data on the programme’s impact, including relevant contextual information. This enables assessment of whether observed changes or improvements are a result of flow coaching activities.

The Health Foundation has commissioned Ipsos MORI (in partnership with The Strategy Unit) to undertake a summative evaluation of the FCA. This evaluation will seek to understand the overall impact of the programme during its 5 years of operation.

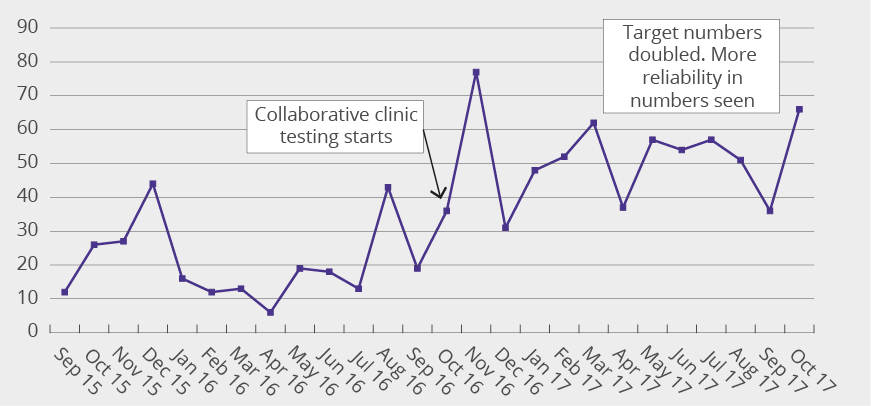

The capacity and capability to access, collect and analyse impact data is scarce