Key points

- The government has set out an aim to ‘level up’ the country, promising to increase prosperity, widen opportunity and ensure that no region is left behind. Action to ‘level up the nation’s health’ has also been described as a core part of this agenda. Yet levelling up is an opaque term, and the government’s plans are still under construction.

- As work gets underway on a levelling up white paper, there is an opportunity to take forward a more broad-based approach to improving prosperity. We examine what a strategy to level up should contain, assess the approach taken by the government so far, and outline some key elements that should feature in the forthcoming white paper.

- While there are encouraging signs, levelling up funding and policies laid out so far are partial and fragmented. Measures of health are not yet influencing the initial allocation criteria for levelling up funds, and initiatives are firmly tilted towards boosting financial and physical infrastructure capital. The role of local government and the NHS in helping to level up is also underplayed.

- A more balanced view of the factors that shape people’s health and impact on the prosperity of a local place is needed in the forthcoming levelling up white paper. Attention should be paid to investing in all four capitals: financial/physical, human, social and natural.

- Good health is interconnected with all of these assets and vital to creating prosperity. Action to improve health and reduce inequalities therefore needs to be a core component of the government’s levelling up approach. A broader set of metrics should be used to target funding and assess progress, with short and longer term measures of health and wellbeing taken into account.

- Any plan to level up health should be underpinned by three interlinked elements: a strategy to improve health and reduce inequalities that genuinely aligns priorities across different government departments; a real partnership between national and local government; and a greater role for the NHS in improving population health.

Introduction

‘Levelling up… is about improving living standards and growing the private sector, particularly where it is weak. It is about increasing and spreading opportunity, because while talent is evenly distributed, opportunity is not. It is about improving health, education and policing, particularly where they are not good enough. It is also about strengthening community and local leadership, restoring pride in place, and improving quality of life in ways that are not just about the economy.’

– Government briefing on the Queen’s Speech (May 2021)

‘Levelling up’ has become an earworm. What it means for government policy is still being worked out. Clues have come in the 2019 Conservative manifesto, the Treasury’s Plan for Growth published in March, and more recently in the Queen’s Speech – which featured levelling up as the main theme. The basic objective appears to be improving prosperity for people living outside of London and the South East. For decades economic performance and productivity across the UK has been severely lopsided, with the UK economy the most regionally unequal out of 26 developed countries.

The policies outlined so far focus largely on boosting prosperity and widening opportunity through improving infrastructure, skills and innovation. Yet as well as developing financial and physical infrastructure – for example through new hospitals and technology – investment in other ‘capitals’ is critical to our future prosperity (see Box 1). To the public, prosperity means the overall quality of their lives and local communities, not just their economic livelihood and local GDP or productivity growth.

We also know that health is a key part of prosperity. Good health is not just personal, but a collective national asset that improves wellbeing, productivity and the ability of individuals to contribute to their families, communities and wider society. In the areas of England with the lowest healthy life expectancy, more than a third of 25 to 64 year olds are economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability. Aside from the human toll, much of this is very costly and avoidable.

Since 2010, improvements in life expectancy in England have slowed more than in any other European country. The gap in the number of years people can expect to live in good health (healthy life expectancy) has also widened between rich and poor. In Hartlepool boys born today can expect to live 57 years in good health; in Richmond-upon-Thames, 71 years. A person’s life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are closely correlated with their income and wealth, with poorer health limiting the opportunity for good-quality, stable employment, and poverty in turn associated with worse health outcomes. Improving the nation’s health and narrowing the health gap across different areas of the country, and between different groups, are a logical focus of government efforts to level up.

The government’s levelling up strategy is still under construction. A white paper is promised later this year, overseen by a new dedicated team of civil servants working across Number 10 and the Cabinet Office, and its delivery will be a focus of a resurrected Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit. There are signs the government recognises that improving health is key to increasing prosperity, as referenced in the Queen’s Speech. Matt Hancock, former Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, also stated that ‘improving the disparities in healthy life expectancy is absolutely at the core of our levelling up agenda.’

But will the government’s plan really include health at its core? And what might be the most impactful approach to level up health? In this briefing we explore what a strategy to level up should contain, examine the approach taken by the government so far, and assess whether better health is likely to be supported. We conclude by outlining some key elements that should feature in the forthcoming white paper.

What does ‘levelling up’ mean?

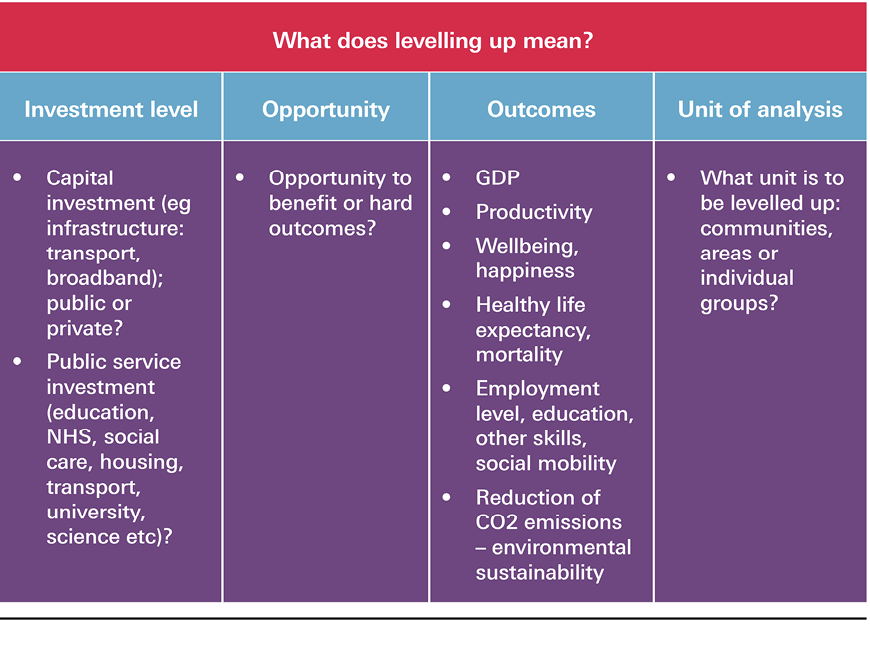

As currently used, levelling up is an opaque term. Any forthcoming government strategy will first need to define prosperity, clarify what exactly is to be levelled up, the target area or group, and the rationale for investment.

Defining ‘prosperity’

Ensuring that ‘no region is left behind’ and that ‘everyone has the same opportunities to get on in life’, seems to be the focus as stated so far by government. Yet in recent government initiatives linked to levelling up, such as those outlined in the government’s paper Build Back Better: Our Plan for Growth, prosperity is not well defined or takes on a meaning narrowly restricted to economic growth, jobs, or productivity. Following work by the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission in 2009, looking ‘beyond GDP’ in measuring economic performance and social progress, many are adopting a wider definition of prosperity. Countries such as New Zealand, Scotland and Wales, as well as international agencies, now use some variation of the ‘four capitals’ approach (see Box 1) to guide policy and significant investment.

The Bennett Institute for Public Policy has emphasised that sustained prosperity will ‘depend on stewardship of the whole portfolio of a society’s assets’, which need to be ‘properly measured and understood’. James Heckman’s work has also set out the gains to be had from investing in the early and equal development of human potential – an approach that pays dividends for future generations by creating a more capable, productive and valuable workforce. These approaches recognise that in addition to financial/physical capital, human capital (physical and mental health as well as people’s knowledge and skills); social capital (including the cohesiveness of communities, culture, local identity and pride); and natural capital (aspects of the natural environment needed to support life and human activity) are all vital to create opportunities for people to thrive.

Box 1: The four capitals

Human capital: Encompasses people’s skills, knowledge and physical and mental health. These factors enable people to participate fully in work, study, recreation and in society more broadly.

Social capital: The norms and values that underpin society, including levels of trust, the rule of law, cultural identity, and the connections between people and communities.

Natural capital: All aspects of the natural environment needed to support life and human activity including land, soil, water, plants and animals, as well as minerals and energy resources.

Financial/physical capital: All the things that make up the country’s physical and financial assets, which have a direct role in supporting incomes and material living conditions. This could include, for example, new houses, roads, buildings, hospitals, factories and equipment.

Where does health fit in?

While health is generally considered to be a part of human capital in such frameworks,, good health also has wider social and economic value. It underpins and interconnects with many other assets. For example, in relation to financial/physical capital, there is a well-evidenced positive association between health status, economic growth and labour productivity. Poor health can mean individuals are unable to participate in the labour market altogether or limit the amount or nature of the work they do, incurring an estimated cost to the UK economy of £100bn per year in lost productivity.

Developing a ‘physical impairment’ doubles the probability that a person will experience a reduction in productivity, while the onset of clinically poor mental health trebles the risk. The quality of the physical environment (including green space and housing) and material living conditions also have a significant impact on people’s ability to live healthy lives. With regards to social capital too, there is well-established evidence that relationships are important for good health. Loneliness is a strong predictor of poor health (with living alone also associated with increased health care use among older adults). By contrast, people with high levels of social capital are likely to have better health.

What is to be levelled up?

Other dimensions are important to clarify as part of a levelling up strategy (outlined in Box 2). For example, what exactly is to be levelled up, and are hard outcomes or widening opportunities the real aim? What is the target unit to be levelled up (for example, deprived towns, regions, neighbourhoods or specific population groups)? And would the target be areas or population groups hardest hit by the pandemic, or those with more deep-rooted structural issues – for example, areas endemically ‘left behind’ due to long run changes in the wider economy, or populations long held back by poverty or education?

Other considerations include the timeframe for achieving goals of the investment – whether these are short, medium and longer term objectives – and how various investments or initiatives are intended to influence prosperity. It will also be important to establish whether the strategy should be nationally or locally driven, and the rationale for this, as well as specifying the underlying assumptions about how levelling up can be achieved successfully through the targeting and timing of investment. The assumption that economic growth and infrastructure capital will automatically improve social and human capital in deprived communities needs hard scrutiny.

Box 2: Basic dimensions of levelling up

* There are some helpful moves in this direction. For example, in December 2020 the Treasury revised the Green Book to help ensure investment decisions are better aligned with strategic government objectives – including those relating to ‘levelling up’. This included putting more weight on environmental, social and place-based impacts as part of business cases put forward to the Treasury for public investment (House of Lords Library, Government investment programmes: the ‘green book’; March 2021 (https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/government-investment-programmes-the-green-book).

The government’s current approach to levelling up

While many existing government policies target the broad issues outlined in Box 2, we examine policies that have recently been linked to the levelling up agenda: the government’s paper Build Back Better: Our Plan for Growth; and the programme for the next parliament outlined in the Queen’s Speech. Here, we assess the extent to which these reference the goal of improving health.

Build Back Better: Our plan for growth

The government’s plan for growth was published alongside the 2021 Budget, superseding the 2017 Industrial Strategy developed under Prime Minister Theresa May. While the plan for growth is an aspirational document without much detail on implementation, it comes with significant public investment over the next 5 years – at a time when public funds for other activities are likely to be constrained.

Levelling up is highlighted as a key cross-cutting objective and as the government’s ‘most important mission’. Three core ‘pillars’ of investment are set out: infrastructure (£600bn over the next 5 years); skills (in particular technical and basic adult skills); and innovation (R&D). A total of 17 new and existing funds are detailed, with the Levelling Up Fund, Towns Fund, UK Community Renewal Fund and the UK Shared Prosperity Fund specifically focused on levelling up. These funds are summarised in Box 3.

Box 3: Funds focused on levelling up

The Levelling Up Fund

An initial £4bn for England over the next 4 years has been committed as part of a new ‘Levelling Up Fund’, with at least £800m set aside for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The fund focuses on three themes: town centre and high street regeneration; improving local transport connectivity and infrastructure; and maintaining and regenerating cultural, heritage and civic assets. It is especially intended to ‘support investment in places where it can make the biggest difference to everyday life, including ex-industrial areas, deprived towns and coastal communities’. Local authorities are categorised into one of three priority groups, with those deemed to be in greatest need receiving funding to help in preparing bids. The criteria used were: need for economic recovery and growth; need for improved transport connectivity; and need for regeneration. The resulting categorisation makes no reference to health and bears little relation to markers of socioeconomic deprivation. Research by the Financial Times showed that 14 areas in England considered more prosperous than the national average were placed in the highest priority group for the Fund.

The Towns Fund

In July 2019, the Prime Minister announced that 101 towns across England would be supported with funding through ‘Town Deals’, with 86 areas selected for funding so far following announcements at the March 2021 Budget and more recently in June 2021.,, Composed of various strands including the High Streets Fund, the Towns Fund provides £3.6bn overall to ‘drive the economic regeneration of deprived towns and deliver long-term economic and productivity growth’. Investment is similarly focused on urban regeneration, planning and land use; skills and enterprise infrastructure; and connectivity.

541 towns in England have been designated by MHCLG as potentially eligible for ‘Town Deals’, with the bidding process again run competitively. In the selection process areas were ranked on seven criteria: income deprivation; skills deprivation (proportion of working-age population with no qualifications at NVQ level); productivity; EU exit exposure; exposure to economic shocks; investment opportunity; and alignment to wider government intervention. While it includes brief references to ‘natural capital’ (creating quality green space that can improve health and wellbeing) and aims to encourage active travel, the Towns Fund Prospectus again includes little mention of health, and no direct account is taken of an area’s healthy life expectancy or other indicators of population health.

UK Community Renewal Fund (2021) and UK Shared Prosperity Fund (from 2022)

The UK Community Renewal Fund (UKCRF) was also launched with the March 2021 Budget, providing local areas with access to £220m funding in preparation for the soon to be established UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF). 100 priority geographical areas for investment have been identified based on an index of ‘economic resilience’ (productivity, household income, unemployment, skills and population density). While there is reference to how the UKCRF will contribute to ‘natural capital’ (net zero and environmental objectives), again there is no mention of measures to improve health and wellbeing in the terms set out.

The UKSPF will replace EU structural funding from 2022, which has historically been spent on areas including inclusive labour markets, skills for growth, promoting social inclusion and combatting poverty. The government has committed to ensuring total domestic UK-wide funding at least matches EU receipts to reach an average of around £1.5bn a year. One element will target places most in need across the UK, such as ex-industrial areas, deprived towns and rural and coastal communities to ‘spur regeneration and innovation’ as well as ‘enabling joined-up, holistic investment to support local communities and people’. A second portion of the UKSPF will focus on employment and skills programmes for those most in need of support. While the precise focus of the UKSPF is still to be developed, so far there has again been no mention of programmes designed to support better health.

The programme set out in the Queen’s Speech

Levelling up was the central theme of the 2021 Queen’s Speech, setting out the government programme over the next parliamentary session. The priority is ‘to deliver a national recovery from the pandemic that makes the United Kingdom stronger, healthier and more prosperous than before’ and to achieve this the government has promised to ‘level up opportunities’. In the background briefing note accompanying the Queen’s Speech, there was a welcome acknowledgement that ‘our health is our most important asset’, shaped by multiple factors that are influenced by a range of central government departments.

The programme laid out a mixture of legislation and initiatives. Centre stage is investment to ‘beat COVID and back the NHS’, with funding for the vaccines programme and a recovery plan for the NHS to tackle the backlog of care. On legislation, 30 bills were promised on a wide range of topics.

The government also confirmed it will publish a white paper on levelling up, ‘setting out bold new interventions to improve livelihoods and opportunities throughout the UK’. Much in the briefing note reaffirms the approach outlined in the plan for growth. This includes funds to regenerate local places; enterprise and jobs measures (eg setting up at least eight freeports); plans to ‘level up public services’ (focused on new hospitals and additional nurses and police officers); skills and education policies (eg a new Lifetime Skills Guarantee); as well as infrastructure and connectivity. The government also promised to ‘bring forward proposals that address racial disparities, support disabled people and help eradicate barriers facing different groups’.

On the Health and Social Care Bill, the Queen’s Speech briefing states that the NHS and local authorities will be given the ‘tools to level up health and care across England so people can live healthier, longer and more independent lives’. There is a separate section on the prevention of ill health, outlining plans to tackle the key risk factors of obesity, air quality, smoking and drug misuse. The role of the new Office for Health Promotion is also mentioned, which the government intends to ‘lead national efforts to improve and level up the public’s health’.

† A Town Deal is an ‘agreement in principle between government, the lead council and the Town Deal Board. They are aimed at setting out a ‘vision and strategy for the town, and what each party agrees to do to achieve this vision.’ Town deals are supported via the government’s Towns Fund. (www.gov.uk/government/news/thirty-towns-to-share-725-million-to-help-communities-build-back-better).

‡ Following an announcement about the abolition of Public Health England in September 2020, a new Office for Health Promotion was announced by the government in March 2021, to be overseen by the Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty. The Office will sit within DHSC and ‘lead work across government to promote good health and prevent illness’ (www.gov.uk/government/news/new-office-for-health-promotion-to-drive-improvement-of-nations-health).

Is the government’s levelling up approach likely to support better health?

While there are encouraging signs, the approach laid out so far is partial, not yet comprehensive and coherent, and measures to improve health do not feature strongly. The ways in which new investment to boost infrastructure, innovation and technical skills might act to improve health in areas of the country that are most in need of levelling up has not been made explicit. Nor does there yet appear to have been consideration of how any new spending might link to existing government programmes with similar objectives.

Lack of focus on health

The plan for growth acknowledges a link between health and how prosperous a place is, and observes that differences in levels of human capital between places and regions (including health) are an ‘important explainer of differences in regional outcomes’. It also recognises that good health and education determine life chances, wellbeing and social connection, promising to ‘strengthen vital public services’ to address disparities. The NHS is mentioned mainly as a recipient of future investment, with its potential to contribute to inclusive local economic development unexplored, and its role in addressing wider determinants of health beyond care undeveloped.

Initiatives are firmly tilted towards boosting financial/physical infrastructure capital. As noted by the Commission on Civil Society, the top five programmes announced by value (worth £150bn) are all investments in physical infrastructure such as transportation, housebuilding and broadband, compared with just £8.7bn of levelling up funding allocated to programmes linked more directly to social objectives.

Investment criteria excluding health

In the prospectuses for the three main investment funds noted in Box 3, good health is hardly mentioned as an asset to be developed. Measures of health are not yet influencing the initial allocation criteria for these levelling up funds, even as a secondary objective.

For the Levelling Up Fund, all local authority areas in England have been grouped by priority according to the criteria set out on Box 3. Those that have been selected into the highest priority group (priority group 1) do not have the greatest health needs: lower tier local authorities (LTLAs) in priority group 1 are in the least deprived half of the country and have above average male healthy life expectancy. Only three LTLAs in priority group 2 are in the country’s most deprived fifth and have below average male healthy life expectancy. 11 of the lower tier local authorities in the government’s lowest priority group 3 are also located in the most deprived half of the country and have below average male healthy life expectancy – see Figure 1.

Source: ONS, local authority healthy life expectancy, 2009–2013; MHCLG, English indices of deprivation, 2019, DfT, HMT, MHCLG, Levelling up Fund list of local authorities by priority category, March 2021.

Figure 2 compares the priority grouping used for local authorities in England to receive the Levelling Up Fund, against male healthy life expectancy for those areas. The 30% of local authority areas in England with the highest score were in priority group 1. Of the 93 local areas with male healthy life expectancy in the lowest 30% for England, only 58 are included in priority group 1. In other words, there are 35 local authority areas with very low healthy life expectancy that are not a priority for investment via the Levelling Up Fund. Prioritising funding based on criteria that also takes into account population health would lead to a significantly different allocation of funding.

Source: ONS, local authority healthy life expectancy, 2009–2013; DfT, HMT, MHCLG, Levelling up Fund list of local authorities by priority category, March 2021.

Centralised focus and an underplayed role for local government

Much of the agency to regenerate local areas and to improve health (for example through better housing, education and early years support) rests with local government. But rather than receiving long-term investment to level up based on a broad assessment of local need and assets, local authorities are required to compete for various pots of central funding for infrastructure, with funding distributed based on centrally-decided criteria.

The pitfalls of relying on a centralised competitive process have been recognised by the Industrial Strategy Council (ISC) and the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee in its recent report Post-pandemic economic growth: Industrial policy in the UK. As well as noting that too many of the plan for growth’s initiatives are unconnected and spread thinly, the ISC has raised concerns that a competitive approach could ‘limit the scope for co-creation between national and local actors’ and generate an uneven playing field by ‘disadvantaging those areas with least capacity and capability to mount a successful bid’. The Local Government Association and Institute for Fiscal Studies have also warned that a complex array of funding pots could duplicate efforts to write bids and lead to a disjointed result.

A centralised approach also appears to run counter to the direction of policy taken in previous years of devolving powers to local government, for example through greater autonomy for metro mayors and city regions. A ‘Devolution and Recovery’ Bill addressing the powers of local government in England was promised in the 2019 Conservative manifesto, blown off course by the pandemic, and is now set to be included in a forthcoming levelling up strategy.

In the absence of progress on this, local authorities and combined authorities/city regions with metro mayors have to varying degrees developed their own plans for improving prosperity – in part based on the government’s previous industrial strategy. The plan for growth also does not mention a role for Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), and the status of Local Industrial Strategies (a central plank of the 2017 Industrial Strategy) is currently unclear. This is despite the potential for local industrial strategies to be an effective vehicle for government investment, and to provide a platform for more inclusive economic development geared towards improving health and reducing inequalities.,

What should a cross-government strategy to level up health look like?

As the government’s strategy for levelling up is still developing, there is an opportunity to achieve a more balanced approach to improving prosperity. In the forthcoming white paper, all ‘four capitals’ should be invested in, with a strategy to improve health as a core component and attention paid to populations with the poorest health.

There are already sizeable investments earmarked to help with levelling up. Yet at present, the approach is partial and funding pots are fragmented in their conception, criteria for distribution, and management. An intelligent strategy will need to reach across most government departments to join up policy, and ensure that improved health and wellbeing is prioritised as part of economic recovery with a mix of short and longer term objectives. The value of existing funding and of any new investment could be maximised by making health improvement a core objective, ensuring that investment is not spread too thinly around the country to make a difference, and developing investment objectives that are linked with existing initiatives and spend across government to maximise impact.

Given the scale of funding pledged, and with the fund’s precise scope still to be defined, there is a particular opportunity for the UKSPF to be used strategically from 2022 as a vehicle for a more broad-based and coherent government approach. Without this, the impact of new and existing investment will not be maximised, and the stalling health improvements seen over the past 10 years will continue, acting as a brake on post-pandemic prosperity and opportunity.

In any strategy to level up health, three interlinked elements should be developed:

- a strategy to improve health and reduce inequalities, genuinely aligning priorities and investment across different government departments

- real partnership between national and local government

- a greater role for the NHS in population health.

A cross-government strategy to improve health and reduce inequalities

(i) Boosting action on the wider determinants of health

Health can only be improved over the long term by prioritising the root causes of ill health and inequality. There is no simple solution to this: action across a range of areas is required that are well beyond the span of the Department of Health and Social Care, or the ability of the NHS, to influence.

One key area of focus should be economic regeneration, with efforts made to boost local employment and income, in turn helping to improve population health. Another should be bolstering public services in ways designed to improve people’s health and wellbeing, thereby maximising their potential and ability to contribute to society. This might include, for example, making good-quality childcare available; supporting children in their early years and at transitions in their late teenage years; subsidising transport for young people; reducing low-quality jobs; boosting the social security system to ensure adequate support for families; ensuring access to green spaces and clean air; and facilitating more active travel. These are all areas where action can be taken centrally and locally to support people to live healthier lives, and there is already enough evidence on what works to make significant progress.

The need for a more coordinated cross-government approach is increasingly being recognised., The government has already set out a number of relevant commitments that can be developed into an ambitious strategy. Most notable in relation to population health is the ‘grand challenge’ – reiterated in the 2019 Conservative manifesto – to ensure people are able to live an extra 5 years of healthy life by 2035, while ‘narrowing the gap between the experience of the richest and poorest’.

Following the abolition of Public Health England, a new ‘Office for Health Promotion’ and cross-ministerial board is also being established this year with the promise it will ‘help inform a new cross-government agenda’ to drive improvements in the nation’s health. To be more effective than previous efforts, a truly cross-cutting approach would be better owned and driven by the very centre of government to secure and sustain action over the longer term. A cross-ministerial board with teeth should be formed: for example, reporting directly to the Prime Minister, attended by secretaries of state and with a secretariat provided by the Cabinet Office to act as a broker across government. The programme should be firmly linked to the wider levelling up agenda.

Binding targets, as well as new mechanisms and institutions, should also be considered to drive sustained improvements in the nation’s health. There is a lot to learn from the attempts of previous governments, such as the health inequalities strategy in operation in England from 1997–2010. Models such as the Future Generations Commissioner established in Wales, or New Zealand’s Wellbeing Budget, are also examples of mechanisms that could aid progress.

(ii) Taking a population-level approach to preventing risk factors for ill health

Ambitious action on the leading modifiable risk factors underlying ill health – poor diet, lack of physical activity, smoking, alcohol and drug misuse – and the conditions leading to the most prevalent disability (such as mental ill health), should be a key element of a cross-government strategy. Given that most risk factors are strongly modified by wider socioeconomic circumstances, any strategy to level up health must go beyond the emphasis adopted by DHSC in recent years of identifying personal risks to ill health, influencing individual behaviours and rolling out new technology.

Evidence shows that population-level interventions will have more impact on increasing healthy life expectancy than relying on individual agency to bring about change., A range of policy levers are known to work, and more should be explored to create healthier environments – including taxation, regulation, increased spending on local public health interventions, and actions designed to alter the availability and marketing of harmful products. Working on these ‘commercial determinants of health’ will require a variety of approaches – from regulatory changes to working with key relevant businesses to modify their products or advertising. Consideration of how government could work with large investors to nudge businesses to do more to improve population health, is another area ripe for development. There is already a precedent for this, with growing action by investors to persuade companies to reduce their carbon emissions in support of net zero targets, increase sales of healthier food, and improve conditions for the lowest paid workers.,,

(iii) Supporting the care workforce

Work has been shown to have a profound influence on health, with low-quality work potentially worse for health than unemployment. Support for those in the lowest paid jobs with poor terms and conditions, including in the care sector, should also be core to a strategy to level up health. As mentioned previously, however, the Queen’s Speech was notable for the absence of an employment bill and its lack of provisions to protect those who are low paid and in insecure work.

While public sector workers already have basic protections in their employment contracts, there are many workers who are not directly employed but still provide vital public sector services without those same protections. Many of those people work in social care. Care work is also disproportionately undertaken by those who are already more socioeconomically disadvantaged, including women (who make up 82% of the workforce) and people from minority ethnic backgrounds. By improving the health and wellbeing of essential workers, boosting their spending power and helping to stabilise a social care system that is under pressure, multiple aspects of the government’s agenda could be supported. Despite some of the most ill and vulnerable in society depending on social care services, a quarter of care workers are employed on zero hours contracts, increasing numbers are paid at or close to the National Living Wage, there are over 100,000 vacancies across England, and turnover is high.

Better partnership between national and local government

Levelling up is far too complex a task for central government to lead alone. Much of the agency to regenerate a local area economically, as well as to act on other wider determinants of health, is the responsibility of local government. Being much closer to communities than Whitehall, local authorities are more easily able to assess where investment is likely to be most impactful. In designing a strategy to improve and level up health, local government should therefore be heavily involved and given considerable autonomy to invest in areas and communities with the greatest needs, tapping into their experience of ‘what works’. This links with the need to develop a future strategy for devolution within England, due to form part of the forthcoming levelling up white paper.

While local authorities have a core role locally, an effective strategy to level up health will need to be based on collaborating with many outside government. The Bennett Institute for Public Policy has noted there is a large ‘ecosystem’ of national and subnational stakeholders relevant to building prosperity that should be engaged. Alongside local government in all its forms (local authorities, mayoral combined authorities and non-mayoral combined authorities), other public authorities including the NHS, police and bodies such as Natural England, will need to be engaged. The third sector and local private business representatives will also need to be involved, such as the Confederation of British Industry and local Chambers of Commerce. It will be critical to draw in these different perspectives for successful design,, ownership, implementation and impact.

Plans can be developed between central and local government, and other key stakeholders, today. But it must be acknowledged that the decade after 2010 saw significant cuts to the baseline budgets of local authorities which have eroded their capacity to improve health and boost prosperity. Services that are vital for levelling up that have been cut substantially over the past decade include housing, education, early years, social care, and public health. Before the pandemic, council spending on local public services had dropped by 23% since 2009/10 – equivalent to nearly £300 per person. More deprived areas fared the worst, with an increasing reliance on council tax meaning that poorer areas – those less able to raise as much from council tax and more dependent on funding from grants and redistributed business rates – experienced bigger cuts. Despite good evidence that spend on public health is highly cost effective, the public health grant is also 24% lower on a real-terms per capita basis than it was in 2015/16 following years of cuts.

The forthcoming Spending Review should acknowledge the key role of local government in levelling up prosperity by adequately funding local authority baseline budgets, and by investing in sector-led improvement to build capacity.

A greater role for the NHS

A striking feature of the levelling up approach to date has been the lack of discussion about how the NHS itself – England’s largest ‘industry’ and a key employer based in all parts of the country – can contribute to prosperity beyond its core role in providing health services.

For the population as a whole, health care services by themselves make only a minor contribution to overall health outcomes, next to other factors such as poverty, employment, early life, and education. But the NHS is a huge organisation and taken in its entirety has an annual budget of £150bn, with 1.5 million staff directly employed. How might it do more to boost population health through action on economic regeneration and on the wider determinants of health?

(i) Boosting economic capital: prosperity and jobs

The NHS is the largest employer in the UK. On top of existing staff shortages of over 100,000, our projections of future trends in demand and supply for health care (based on pre-COVID-19 data) point to the need for over 230,000 more NHS staff by 2025/26. As part of its normal business, and provided it is given investment commensurate with need, the NHS will be able to employ and train a significant number of those seeking work in future – particularly in areas that need to be levelled up where there may be fewer opportunities.

The same is true for social care. Currently the adult social care workforce employs around 1.52 million people in 1.65 million jobs in England. If the workforce grows in proportion to the number of people aged 65 and older, then an extra half a million jobs will be needed by 2035, again in many areas needing to be levelled up.

As health care is a globally expanding industry, the NHS’s role to boost enterprise through research and development, innovation and life sciences is central. For many years the ‘innovation health and wealth’ agenda has been pursued through a variety of policies and initiatives., In the wake of the pandemic there will be renewed emphasis on this as part of attempts to drive successful enterprise for the UK globally, including through vaccine development and trials for example. Given the domestic priority of levelling up, and the increasing recognition that ‘place matters’, the obvious opportunity now is to pursue this agenda while developing current regional and local initiatives that are more explicitly designed to benefit local people through employment. This is especially the case in areas outside of the ‘golden triangle’ of research institutions in Oxford, Cambridge and London. Such activity is already happening and has accelerated due to the pandemic in areas such as Manchester, Leeds and Newcastle, with activity linked to government investment., The key will be to boost these existing efforts by linking such initiatives with new levelling up funding as part of an explicit strategy – countering the ‘spread too thinly to be effective’ argument for new investment, and adding value to existing levelling up investments.

While central government can and should act on these issues, reforms in the NHS Long Term Plan, and in the recently published Health and Care Bill, aim to boost collaboration between NHS bodies and other local stakeholders, such as local authorities, within and across integrated care systems (ICSs). ICSs – like the Greater Manchester Health Partnership – boost critical mass and skills, helping local agencies make faster progress on economic regeneration while improving health and care. Again, there should be strategic join-up between a national levelling up agenda (and a new partnership with local government) alongside these developments on the ground – to multiply the impact of the public funds invested.

(ii) The NHS as an anchor institution

First developed in the US, the term ‘anchor institution’ refers to large, typically non-profit, public sector organisations whose long-term sustainability is tied to the wellbeing of the populations they serve. Anchors get their name because they are unlikely to relocate (for example as a business might do in the event of an economic downturn), and have a significant influence on the health and wellbeing of communities.

The NHS can act in a national role and locally as an anchor in several ways.

Nationally

The NHS exists to provide universal access to health care based on need, not the ability to pay. Due to funding formulae that has explicitly taken into account health need since the 1970s, tax funds for the NHS per head of population are now distributed more evenly across the country (England) than other public services.

But while overall resource allocation (funding per capita) might reflect need, where NHS facilities are located (where staff are employed, care is delivered, supplies are procured from) may do so to a lesser extent. For example, the past 20 years have seen a large number of closures or mergers of hospitals, and beds managed by community trusts reduced, many affecting small towns. In 2019, 19 NHS trusts were earmarked for closure. These plans are likely to have been made to improve the quality of care (the NHS’s core objective) and boost efficiency, rather than to support the local community through maintaining employment (which would in turn help to improve health). The past two decades have also seen relatively low investment in primary care relative to hospital care and a persistence of the ‘inverse care law’ in general practice, with more deprived populations served less well than wealthier ones.

The impact of major reconfiguration decisions (such as facility closures) on local social capital and employment opportunities could be a greater factor in decision making, particularly for those facilities serving more deprived communities and in areas with little industry. The NHS is under huge pressure to improve the quality of care and to operate as efficiently as possible within a given budget. Decisions that also account for wider public value to a community may need to attract extra central subsidy to achieve that objective; for example, from levelling up investment funds. The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 already requires NHS commissioners to consider broader social, economic and environmental benefits to their local populations when making commissioning decisions. But the extent to which this is happening, or is impactful, is unclear. While this will be boosted by provisions in the recently published Health and Care Bill, the incentives for the NHS to achieve greater value for money will strongly act against these wider considerations.

Procurement is an obvious area where the incentives may also work against the goal of improving social value locally. Sourcing supplies locally in the NHS may be inefficient, not least because of the time and administration involved, but also because the NHS may not then maximise its more collective purchasing power to drive up quality and drive down cost. In the wake of the pandemic for example, the Department of Health and Social Care is looking again at how technology can be effectively supplied to the NHS.

The NHS can make the most of its role as a major employer by incentivising recruitment and retention in areas with chronic shortages, setting fair national pay rates for staff, continuing to improve health and wellbeing at work (a particularly pressing task given the high stress levels reported in NHS staff surveys) and working to address unfairness and discrimination in all its forms. Recent policies have paid attention to these issues. For example, the system of terms and conditions for NHS staff (‘Agenda for Change’) has focused on improving pay rates for the lowest paid. There are policies to develop staff and their wellbeing through the NHS People Plan, and there is a Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) requirement for NHS commissioners and NHS health care providers in the standard NHS contract. Further progress is still needed.

Locally

Over and above providing care and joining with partners to boost employment and innovation, NHS organisations can make a further contribution to the prosperity of a place. This can include, for example, adapting the way people are employed as well as the way goods and services are purchased and buildings and spaces are used. The potential for the health service to create this type of social and environmental value in local communities is recognised in the NHS Long Term Plan, and a number of trusts, systems and other partners are aiming to make progress by participating in a UK-wide Health Anchors Learning Network, co-funded by NHS England and NHS Improvement and the Health Foundation.

Examples of local anchors work on the ground can be found in areas like Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust, which has developed a number of initiatives aimed at working with and better understanding its local community, including an employment dashboard designed to support access to work and measure progress in tackling inequalities. The dashboard combines hospital data (including the roles and demography of staff and vacancies mapped to local deprivation), with council data (local demographics and the aspirations of young adults). In Newcastle, a cross-sector partnership has been set up by the NHS and other local bodies with a strong focus on targeting areas of deprivation and ensuring inclusive local recruitment.

The role of integrated care systems (ICSs)

A key thrust of the NHS Long Term Plan was to develop ICSs – partnerships between NHS organisations, local government and other agencies designed to coordinate local services and improve population health. ICSs have been created in 42 areas of England, covering populations of around 1 to 3 million. The latest reforms to the structure of the NHS in England (as outlined in the government’s Health and Care Bill) develop this agenda further, and more formal versions of ICSs are likely to be established in 2022.

ICSs offer an opportunity to strengthen the NHS’s role in preventing disease and reducing inequalities. This includes collaboration with local government and other community groups to identify and address social factors that shape health, such as food insecurity and social isolation. While the previous versions of ICSs (Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships) developed 5-year plans for improving local health and care in 2016, analysis of these plans found that their approaches to prevention and reducing inequalities were often weak. Most plans included a prevention strategy, but fewer than half specified how NHS agencies would work with local public health teams. Coverage of how these plans would meet national prevention priorities was patchy. The plans were also broadly focused on individual-level approaches to disease prevention, with few describing interventions to address the social and economic determinants of health.

Stronger engagement with local government and more systemic approaches to addressing inequalities will be needed if ICSs are to deliver on their ambitions. Rather than searching for ‘silver bullet’ solutions, local leaders are likely to have the greatest impact by focusing on reshaping the multiple factors that impact on the health of their communities. To reduce rates of obesity, for example, action will be required across health care, food, transportation and other aspects of the local environments in which people live.

England has a long history of partnership initiatives between the NHS and other sectors that have aimed to improve health and wellbeing. Yet evidence about the impact that these partnerships have had on health outcomes and health equity is limited., Communication, culture, resources, management, and other factors are likely to shape partnership success. The potential for local partnerships to have a positive impact is also fundamentally shaped by the broader political context in which they operate – including the level and distribution of funding available for public health, education, and other public policy areas. ICSs will only be able to tackle inequalities as part of a coordinated national approach, which is in turn linked to a broader levelling up strategy for investment.

Measuring progress

Measurement

As noted by the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee in its recent report, it is not clear how the impact (as opposed to delivery) of the levelling up strategy will be assessed – particularly following the recent scrapping of the Industrial Strategy Council. As emphasised previously, at the core of a cross-government strategy to level up must be a more balanced view of the factors that shape people’s health and impact the prosperity of a local place. A broader set of metrics should be used to set targets and assess progress, including measures of health and wellbeing. These could include indicators of healthy life expectancy, mortality, morbidity and wellbeing across the life course that are already monitored by the ONS and PHE. A range of wider wellbeing and health indices and frameworks could also be drawn on. The new ONS Health Index for England, for example, tracks a broad spectrum of 58 indicators to measure the health of the nation and compare different places. These include healthy life expectancy and avoidable deaths; working conditions (including job-related training and low pay); children and young people’s education; access to green space, and access to housing.

Internationally, a number of other indices and frameworks have also been developed that could be drawn on. The World Bank has developed the Human Capital Index, the OECD uses a Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress, and the New Zealand Treasury uses a ‘Living Standards Framework’ based on the ‘four capitals’. The same sorts of indicators could be used to identify areas in greatest need of investment when allocating any future levelling up funding (such as via the UKSPF), to set clear targets for addressing health inequalities, and to better join the dots with existing funding streams.

These metrics should be distinct from progress against the operational delivery of a specific set of government initiatives, which may be prioritised by the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit or the new levelling up taskforce charged with overseeing the strategy.

Accountability

There is a strong case for regular independent monitoring of these wider trends, outwith a government unit/department or central cross-government unit. To an extent, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) performs a function like this for financial capital, the Infrastructure Commission for infrastructure capital, and the independent Committee on Climate Change for some aspects of natural capital. An equivalent regular independent assessment of the nation’s health capital, scrutinised by parliament at regular intervals, would clearly be in the long-term interest – helping to sustain attention over time and build cross-party consensus and accountability on the need for action.

Conclusion

The government’s strategy to level up is still under construction, with the key dimensions and the main objectives yet to be clarified. So far, announced policies and initiatives focus mainly on infrastructure, skills and innovation. While the government has acknowledged the need to ‘level up health’ and recognised its link to economic prosperity, this is not yet reflected in the targeting and allocation of wider levelling up investment – nor in a significant step change in how government collaborates across central departments or with local authorities. There is a huge opportunity now to develop a coherent strategy with a wider concept of prosperity at its core, and to include measures directly designed to improve health and reduce health inequalities as a key component.

The levelling up strategy should include a cross-government plan to act much more effectively on wider factors known to be injuring health and holding back opportunity. These include poor housing, low-quality work, support for children in their early years, and education. Such a strategy needs to be developed with local government, which will be responsible for taking action locally. Any strategy should also include much stronger central action on some of the biggest specific risk factors to health relating to diet, smoking, drug misuse and alcohol consumption – action that could include working with key businesses and major investors.

The strategy and investment should also include support to develop the role of the NHS as an anchor institution. This could cover, for example, measures to make sure the NHS can train and employ the staff needed for the future, to improve the terms and conditions of those in low-quality work, and to consider explicit subsidy to keep open NHS facilities that are a critical supplier of jobs and opportunity to local communities. Such actions should be taken over and above existing investment to boost enterprise and local regeneration through life sciences and technology.

Given the extent of government borrowing resulting from the pandemic (£303bn or 14.5% of GDP in 2020/21), there will be huge pressure to maximise every pound of investment in levelling up. Building back better must mean building up health. To do this, government carrying on as normal will not work. Without a very serious attempt to improve the health of the nation, damaged not just by the pandemic but also by pre-existing effects of austerity and structural economic change, levelling up will remain little more than a slogan. The forthcoming white paper on levelling up, and related expenditure in the Spending Review, will be a key test of the government’s commitment and strategic competence in delivering on its promises.

References

- Davenport A, Zaranko B. Levelling up: where and how? Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS); 2020 (https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15055).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). An overview of lifestyles and wider characteristics linked to Healthy Life Expectancy in England: June 2017. ONS (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/articles/healthrelatedlifestylesandwidercharacteristicsofpeoplelivinginareaswiththehighestorlowesthealthylife/june2017).

- Marmot, M et al. Health Equity in England: the Marmot Review 10 Years On. Institute of Health Equity (IHE); 2020 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on) (p13).

- Tinson, A. Living in poverty was bad for your health long before COVID-19. The Health Foundation; 2020 (www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/living-in-poverty-was-bad-for-your-health-long-before-COVID-19).

- All-Party Parliamentary Group for Longevity. Levelling up health [video]; 9 April 2021 (www.youtube.com/watch?v=0RXo3bmPuPc).

- HM Treasury. Build Back Better: our plan for growth. HM Treasury; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/build-back-better-our-plan-for-growth) (p12).

- Select Committee on Public Services. Oral evidence: “Levelling up” and public services; 21 April 2021 https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/2098/pdf/) (p 1).

- Stiglitz et al. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; 2009 (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf).

- OECD. Policy use of well-being metrics: Describing countries’ experiences. SDD Working Paper No.94; 2018.

- University of Cambridge Bennett Institute for Public Policy. Valuing Wealth, Building Prosperity: The Wealth Economy Project on Natural and Social Capital, One Year Report; 2020 (www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/publications/valuing-wealth-building-prosperity) (p 6).

- The Heckman Equation [webpage] (https://heckmanequation.org/the-heckman-equation).

- Deloitte. The Four Capitals (www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/nz/Documents/public-sector/sots5-fourcapisinfog.pdf).

- New Zealand Treasury. Our living standards framework; 2019 (www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/our-living-standards-framework).

- HSE. Working days lost in Great Britain [webpage]. HSE (www.hse.gov.uk/Statistics/dayslost.htm).

- Bryan M, et al. Presenteeism in the UK: Effects of physical and mental health on worker productivity. The University of Sheffield; 2020 (https://ideas.repec.org/p/shf/wpaper/2020005.html).

- Dreyer K, Steventon A, Fisher R, Deeny S. The association between living alone and health care utilisation in older adults: a retrospective cohort study of electronic health records from a London general practice. BMC Geriatrics. 2018 ;18(269) (bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-018-0939-4).

- Rocco L, Suhrcke M. Is social capital good for health?: A European perspective. World Health Organization; 2019 (www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/is-social-capital-good-for-health-a-europeanperspective).

- HM Treasury, MHCLG and DfT. Levelling Up Fund: Prospectus (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/966138/Levelling_Up_prospectus.pdf) (p 4).

- Ibid (p 1).

- Ibid (p 4).

- Bounds A. Government criticised over design of levelling up fund. Financial Times; 11 March 2021 (www.ft.com/content/3a02454f-ee90-4b19-9fef-2e2c3d98b234).

- MHCLG. Guidance: Towns Fund recipients March 2021; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/towns-fund-recipients-march-2021/towns-fund-recipients-march-2021).

- MHCLG. Press release: Thirty towns to share £725 million to help communities build back better. 8 June 2021; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/news/thirty-towns-to-share-725-million-to-help-communities-build-back-better).

- MHCLG. Press release: PM announces new funding for Cornwall to create a G7 legacy for the region. 8 June 2021; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-announces-new-funding-for-cornwall-to-create-a-g7-legacy-for-the-region).

- Ibid, Towns Fund guidance (p 9).

- MHCLG. Policy paper: UK Community Renewal Fund: prospectus 2021–22. (See: 1.3. Looking ahead to the UK Shared Prosperity Fund). (www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-community-renewal-fund-prospectus/uk-community-renewal-fund-prospectus-2021-22).

- Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street. Speech: Queen’s Speech 2021; 11 May 2021 (www.gov.uk/ government/speeches/queens-speech-2021).

- Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street. Policy paper – Queen's Speech 2021: Background briefing notes; 11 May 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/queens-speech-2021-background-briefing-notes) (p 24).

- Ibid (p 30).

- Ibid (p 6).

- Ibid (p 11).

- Ibid. Build Back Better: our plan for growth (p 72).

- Commission on Civil Society. Levelling Up: On the right track?; 2021 (https://civilsocietycommission.org/ publication/levelling-up-on-the-right-track).

- DfT, HM Treasury and MHCLG. Policy paper – Levelling Up Fund: Prioritisation of places methodology note; 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-fund-additional-documents/levelling-up-fund-prioritisation-of-places-methodology-note).

- Industrial Strategy Council. Annual Report March 2021 (https://industrialstrategycouncil.org/sites/default/files/ attachments/ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf) (p 32).

- MHCLG. Towns Fund Prospectus. November 2019 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/924503/20191031_Towns_Fund_prospectus.pdf).

- Naik Y, et al. Using economic development to improve health and reduce health inequalities. The Health Foundation; 2020 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/using-economic-development-to-improve-health-and-reduce-health-inequalities) (p 19).

- House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee. Post-pandemic economic growth: Industrial policy in the UK. First Report of Session 2021–22; 2021 (https://committees.parliament.uk/ publications/6452/documents/70401/default).

- Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? The Lancet. 1991;26(338)8774:1059–1063.

- House of Lords Public Services Committee. ‘Levelling up’ and public services [letter]; 20 May 2021 (https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5952/documents/67603/default).

- All-Party Parliamentary Group for Longevity. Levelling up Health; April 2021 (https://static1. squarespace.com/static/5d349e15bf59a30001efeaeb/t/6081711f326bde0eea34a3f6/1619095840963/ Levelling+Up+Health+Report+Digital+Final+2.pdf).

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. The Grand Challenges. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy; 2019 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy-the-grandchallenges/industrial-strategy-the-grand-challenges#ageing-society).

- Gov.uk. New Office for Health Promotion to drive improvement of nation’s health; 29 March 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/news/new-office-for-health-promotion-to-drive-improvement-of-nations-health).

- Barr B, Higgerson J, Whitehead M. Investigating the impact of the English health inequalities strategy: time trend analysis. BMJ. 2017;358(8116):j3310.

- Future Generations Commissioner for Wales [webpage] (www.futuregenerations.wales/resources_posts/future-generations-framework).

- Government of New Zealand. Wellbeing Budget 2020: Rebuilding Together; May 2020 (www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/wellbeing-budget/wellbeing-budget-2020-html).

- Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? The Lancet. 1991;26(338)8774:1059–1063.

- Marteau et al. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ February 2021; 372 (doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n332).

- Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. (2016) PLoS Med 13(4): e1001990. (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990).

- Finch D, Briggs A and Tallack C. Improving health by tackling market failure. The Health Foundation; 2020 (www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/improving-health-by-tackling-market-failure).

- UN environment programme. New Icap Framework Drives Investor Action On Climate Crisis. Accelerating Transition To Net-Zero; 2021 (www.unepfi.org/news/industries/investment/new-icap-framework-drives-investor-action-on-climate-crisis-accelerating-transition-to-net-zero).

- Tesco to boost sales of healthy foods after investor pressure. Financial Times; May 2021 (www.ft.com/ content/4ceeae52-3d9f-45f8-8859-91753a4ccebb).

- ShareAction. Workforce Disclosure Initiative [webpage] (https://shareaction.org/workforce-disclosure-initiative).

- Tinson, A. What the quality of work means for our health. The Health Foundation; 2020 (https://health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/the-quality-of-work-and-what-it-means-for-health).

- Skills for Care. The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. October 2020 (www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf) (p10).

- Ibid (p 40).

- CBI. Seize the moment – An economic strategy for the UK. CBI (www.cbi.org.uk/events/economic-vision-86651).

- COVID Recovery Commission. Welcome to the Covid Recovery Commission. COVID Recovery Commission (https://covidrecoverycommission.co.uk).

- Harris T, Hodge L, Phillips D. English local government funding: trends and challenges in 2019 and beyond. Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS); 2019 (www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14563).

- The Health Foundation. Public health grant allocations represent a 24% (£1bn) real terms cut compared to 2015/16. Health Foundation response to announcement of the public health grant allocations for 2021–22; March 2021 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/public-health-grant-allocations-represent-a-24-percent-1bn-cut).

- Local Government Association (LGA). What is sector-led improvement? (www.local.gov.uk/our-support/our- improvement-offer/what-sector-led-improvement).

- Shembavnekar, N. Going into COVID-19, the health and social care workforce faced concerning shortages. The Health Foundation; 2020 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/going-into-covid-19-the-health-and-social-care-workforce-faced-concerning-shortages).

- Skills for Care. The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England; 2020 (www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/publications/national-information/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-in-England.aspx).

- The Health Foundation. Workforce burnout and resilience in the NHS and social care. Our submission to the Health and Social Care Select Committee inquiry; September 2020 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/consultation-responses/workforce-burnout-and-resilience-in-the-nhs-and-social-care).

- DHSC. Accelerating adoption of innovation in the NHS; 2011 (www.gov.uk/government/news/accelerating-adoption-of-innovation-in-the-nhs).

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan: Research and innovation to drive future outcomes improvement; 2019 (www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/better-care-for-major-health-conditions/research-and-innovation-to-drive-future-outcomes-improvement).

- Leeds City Region Enterprise Partnership. Leeds City Region Health Innovation Proposition; August 2020 (www.westyorks-ca.gov.uk/media/4420/recovery-proposition-health-innovation-20200826.pdf).

- Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Integrated COVID Hub North East (https://careers.nuth. nhs.uk/your-career/integrated-covid-hub-north-east).

- The full list of the 19 hospitals facing closure. I news; 13 February 2017 (https://inews.co.uk/news/health/great-nhs-gamble-full-list-19-hospitals-facing-closure-46644).

- Tallack C, Charlesworth A, Kelly E, McConkey R, Rocks S. The Bigger Picture. Learning from two decades of changing NHS care in England. The Health Foundation; 2020 (https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2020-RC10).

- Fisher R. ‘Levelling up’ general practice in England: What should government prioritise?. The Health Foundation; 2021 (www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/levelling-up-general-practice-in-england).

- Health Service Journal. Social value’ key to choosing NHS providers under new procurement regime; 2021 (www.hsj.co.uk/policy-and-regulation/social-value-key-to-choosing-nhs-providers-under-new-procurement-regime/7029488.article).

- Health Service Journal. Exclusive: DHSC reveals procurement shake-up in wake of covid; 2021 (www.hsj.co.uk/finance-and-efficiency/exclusive-dhsc-reveals-procurement-shake-up-in-wake-of-covid/7029965.article).

- Reed S, et al. Building healthier communities: the role of the NHS as an anchor institution. The Health Foundation; 2019 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/building-healthier-communities-role-of-nhs-as-anchor-institution).

- The Health Foundation. Health Anchors Learning Network. The Health Foundation (www.health.org.uk/funding-and-partnerships/our-partnerships/health-anchors-learning-network).

- Allen M, Malhotra A M, Wood S, Allwood D. Anchors in a storm: Lessons from anchor action during COVID-19. The Health Foundation; 2021 (www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/anchors-in-a-storm).

- Gottlieb, et al. Social Determinants of Health: What's a Healthcare System to Do? Journal of Healthcare Management. Jul-Aug 2019;64(4):243-257 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31274816).

- Alderwick H, et al. Sustainability and transformation plans in the NHS: how are they being developed in practice? The King’s Fund; 2016 (www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/stps-in-the-nhs).

- Briggs A, Göpfert A, Thorlby R, et al. Integrated health and care systems in England: can they help prevent disease? Integrated Healthcare Journal 2020;2:e000013. doi: 10.1136/ihj-2019-000013.

- Alderwick H, et al. Healthcare Public Health: Improving health services through population science; 2020 (https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/ view/10.1093/oso/9780198837206.001.0001/oso-9780198837206-chapter-9).

- Rutter H, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. The Lancet Voume 390, Issue 10112, P2602-2604, June 2017 (www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31267-9/fulltext).

- Alderwick H, Hutchings A, Briggs A, et al. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health 21, 753 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10630-1.

- K. E. Smith, C. Bambra, K. E. Joyce, N. Perkins, D. J. Hunter, E. A. Blenkinsopp, Partners in health? A systematic review of the impact of organizational partnerships on public health outcomes in England between 1997 and 2008, Journal of Public Health, Volume 31, Issue 2, June 2009, Pages 210–221, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/ fdp002.

- Alderwick, H., Hutchings, A., Briggs, A. et al. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health 21, 753 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10630-1.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Developing the Health Index for England: 2015 to 2018; 2020 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/articles/ developingthehealthindexforengland/2015to2018).

- New Zealand Treasury. Our living standards framework (www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz- economy/higher-living-standards/our-living-standards-framework).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: David Finch and Adam Tinson for their data analysis, and Hugh Alderwick and Jo Bibby for their contributions. Errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors alone.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL:https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2021-C07