Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the many staff at the Health Foundation who contributed to this work, and to The Commonwealth Fund for their work in conducting the survey. Errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors alone.

About The Commonwealth Fund’s 2019 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Doctors in 11

The Commonwealth Fund provided core support for the survey, with co-funding from the following organisations: The NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation; Victoria Department of Health and Human Services; Health Quality Ontario; the Canadian Institute for Health Information; Commissaire à la Santé et au bien-être du Québec; La Haute Autorité de Santé; the Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés; Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen; the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and Radboud University Medical Center; The Norwegian Institute of Public Health; the Swedish Agency for Health and Care Services Analysis (Vårdanalys); the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health; The Health Foundation; and any other country partners.

Key points

- The Commonwealth Fund surveyed 13,200 primary care physicians across 11 countries between January and June 2019. This included 1,001 general practitioners (GPs) from the UK. The Health Foundation analysed the data and reports on the findings from a UK perspective.

- In some aspects of care, the UK performs strongly and is an international leader. Almost all UK GPs surveyed use electronic medical records, and use of data to review and improve care is relatively high.

- The survey also highlights areas of major concern for the NHS. Just 6% of UK GPs report feeling ‘extremely’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their workload – the lowest of any country surveyed. Only France has lower overall GP satisfaction with practising medicine. GPs in the UK also report high stress levels, and feel that the quality of care that they and the wider NHS can provide is declining.

- A high proportion of surveyed UK GPs plan to quit or reduce their working hours in the near future. 49% of UK GP respondents plan to reduce their weekly clinical hours in the next 3 years (compared to 10% who plan to increase them).

- UK GPs continue to report shorter appointment lengths than the majority of their international colleagues. Just 5% of UK GPs surveyed feel ‘extremely’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the amount of time they can spend with their patients, significantly lower than the satisfaction reported by GPs in the other 10 countries surveyed.

- Workload pressures are growing across general practice, and UK GPs report that they are doing more of all types of patient consultations (including face-to-face, telephone triage and telephone consulting). Policymakers expect GPs to be offering video and email consultations to patients who want them in the near future, but the survey suggests that this is currently a long way from happening. Only 11% of UK GPs report that their surgeries provide care through video consultation.

Introduction

The 2019 Commonwealth Fund survey compares perspectives from GPs across 11 high-income countries. The survey asked GPs’ views on their working lives, changes in how they deliver services, and the quality of care they can provide to patients. Analysis of what the survey data means for the United States health system has been published elsewhere. This publication provides UK-focused analysis of the survey data, including several UK-specific questions funded by the Health Foundation.

The previous Commonwealth Fund Survey in 2015 made uncomfortable reading for policymakers. It showed that UK GPs were the most stressed of the 11 countries surveyed, with more than one in five GPs reporting being made ill by the stress of work in the last 12 months.

Since 2015, pressure on general practice in the UK has increased. In all four countries, the population has grown, and across the UK as a whole, the number of GPs (headcount) per person has fallen. In England, investment in primary care declined relative to the rest of the NHS for a decade until 2014/15, according to NHS England, which has now guaranteed real terms funding increases for general practice for the next 5 years. But despite a target (set in 2016 in the General practice forward view) of 5,000 additional GPs by 2020, the number of fully qualified permanent, full-time equivalent GPs has continued to fall (declining by 1.6% between March 2018 and March 2019). Higher GP workload has negatively impacted on GP morale, increasing the likelihood of GPs leaving the profession or reducing hours, and worsening workforce shortages.

While publicly available data on general practice do not permit direct comparisons between the four UK countries, evidence suggests a similar picture of increasing pressure on general practice in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales (Box 1).

Box 1: Pressures on general practice in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Northern Ireland

- There was an estimated 3.5% decrease in FTE GPs between 2014 and 2018.

- Of 151 GPs surveyed by the RCGP Northern Ireland in 2019, 26% said they were unlikely to be working in general practice in 5 years’ time.

Scotland

- 37% of respondents to the RCGP’s 2018 survey reported feeling ‘so overwhelmed at least once a week that they cannot cope’.

- There was a 4% decrease in the number of FTE GPs between 2013 and 2017, according to the Primary Care Workforce Survey (from 3,735 to 3,575).

Wales

- GPs in Wales reported similar levels of stress to GPs in Scotland in the RCGP survey and 72% thought working in general practice would get worse over the next 5 years.

- The overall number of GPs has increased by 1.2% between 2010 and 2018, but official data do not capture whether GPs are full-time or part-time.

Pressure on GPs is reflected in patient experiences of care. In England, for example, the percentage of patients reporting a good overall experience of general practice is high but declined from 88% in 2012 to 83% in 2019. These pressures also threaten to undermine broader plans for health system reform.

Although responsibility for health services sits with devolved governments within the UK, GP-led primary care is at the heart of plans for service improvement in all four health systems (Box 2). This includes efforts to increase the number of GPs, develop team-based models of primary care with GPs working alongside other health and care professionals, and closer integration of services between general practice, hospitals, social care and other services.

Box 2: Overview of UK reform initiatives for general practice and primary care

Northern Ireland

In 2016, a 10-year strategy was published for the NHS and social care system in Northern Ireland, with the aim of delivering more preventative, person-centred care. The strategy includes changes to primary care, improvements in community and preventative services, and reforms to hospital services (particularly to reduce waiting times). These proposals include expanding the primary care workforce (more physiotherapists, social workers, mental health professionals and others) and developing multidisciplinary teams based in GP-led federations with improved premises. Enlarged primary care teams have so far been rolled out in three of 17 GP Federations. Funding for 200 pharmacists was included in the 2018/19 GP contract.

Scotland

Scotland’s Health and social care delivery plan, published in December 2016, set a broad aim for a healthier population, with services that intervene early, support people to stay well and, if hospital treatment is needed, ensure that people can return home as quickly as possible. Alongside formal integration between NHS and social care services, the plan aims to build capacity in primary and community care, including wider use of different health professionals, such as pharmacists and paramedics, and increasing the number of GPs. Multidisciplinary primary care led by ‘expert generalist’ GPs is built into the most recent GP contract (2018), with GPs as the senior clinical decision maker within teams, some of which include community link workers to connect patients with non-medical services.

Wales

The most recent plan for primary care in Wales is contained in The Strategic Programme for Primary Care. This combines pre-existing reform initiatives (which aimed to improve access and quality) with a new long-term plan for health and social care in Wales set out in A Healthier Wales. A Healthier Wales aims to shift the focus of the health and care system towards ‘wellness’, with more prevention and personalised care outside hospital. Primary care is seen as a key vehicle for achieving this, through social prescribing, better access to general practice, and multidisciplinary teams within primary care. GPs in Wales have been organised into ‘clusters’ since 2010 (covering between 30 and 50,000 registered patients), designed to improve planning and collaboration between practices.

England

In January 2019, NHS England published the NHS Long term plan, which promised a number of changes to the way the NHS works, including a greater focus on prevention and a ‘boost’ to primary care and other out of hospital services. More investment was promised for general practice, and a large part of this investment was channelled through new primary care networks (PCNs) – collaborations of neighbouring general practices covering populations of 30,000 to 50,000 patients. Although not mandatory, PCNs are underpinned by a new GP contract and are the only route for GPs to receive funding for additional primary care staff, including clinical pharmacists and social prescribing link workers (from 2019), physician associates, first contact physiotherapists (from 2020) and community paramedics (from 2021).

The NHS Long term plan also pledges that all patients in England will have the right to be offered digital first primary care by 2023/24, and the 2019 GP Contract in England commits that all patients have the right to online and video consultations by April 2020 and April 2021 respectively.

Against this backdrop, we present our analysis of data from the Commonwealth Fund’s 2019 GP survey – including comparisons with the 2015 survey data where possible.

The data are presented under three main themes:

- How GPs view their job.

- The care GPs provide and how it is changing.

- How GPs work with other professionals and services.

The results are presented for the UK as a whole, with differences between UK countries highlighted only when they are of particular interest. The final section of this analysis discusses the implications of the results and what they mean for policy in England, though the implications we identify are likely to be broadly relevant across the UK. See Methods below and the Appendix for more details of the data and methods used.

Methods

The 11 countries surveyed were: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

13,200 primary care physicians across 11 countries completed the survey, of which 1,001 were from the UK. The survey was completed between January and June 2019. Primary care physicians were recruited through a variety of methods including by post, email, fax, phone and online. In the UK, GPs were asked to complete the survey either online or via phone. The response rate was 26.8%, with 1,001 GPs participating.

There was an international set of 37 questions, and UK GPs were asked an additional set of UK-specific questions, funded by the Health Foundation.

These methods were used in the analysis:

- Weighting: for the 11 country results, data from each country were weighted to ensure the final outcome was representative of GPs in that country based on their demographics (gender, age – and region for the UK) and selected specialty types. See the Appendix for full details.

- Comparison with the 2015 results: few reliable comparisons can be made between the 2015 and 2019 survey results because the wording of most questions and/or responses changed between editions. Where year-on-year comparisons could be made, the statistical significance was calculated for a 95% confidence level, giving a margin of error of 3.5% for the UK.

- Statistical significance: where we report differences between countries these are statistically significant at the 95% level unless otherwise stated.

Further information on methods can be found in the Appendix.

* The margin of error is one side of a confidence interval. So a margin of error of 3.5% for a 95% confidence level means that if the survey were conducted 100 times, you would expect the data to be within 3.5 percentage points above or below the percentage reported in 95 of the 100 surveys. The size of this form of error is largely driven by the sample size, and does not reflect other forms of error, eg due to the way the survey is conducted or the types of people that respond.

How do GPs view their job?

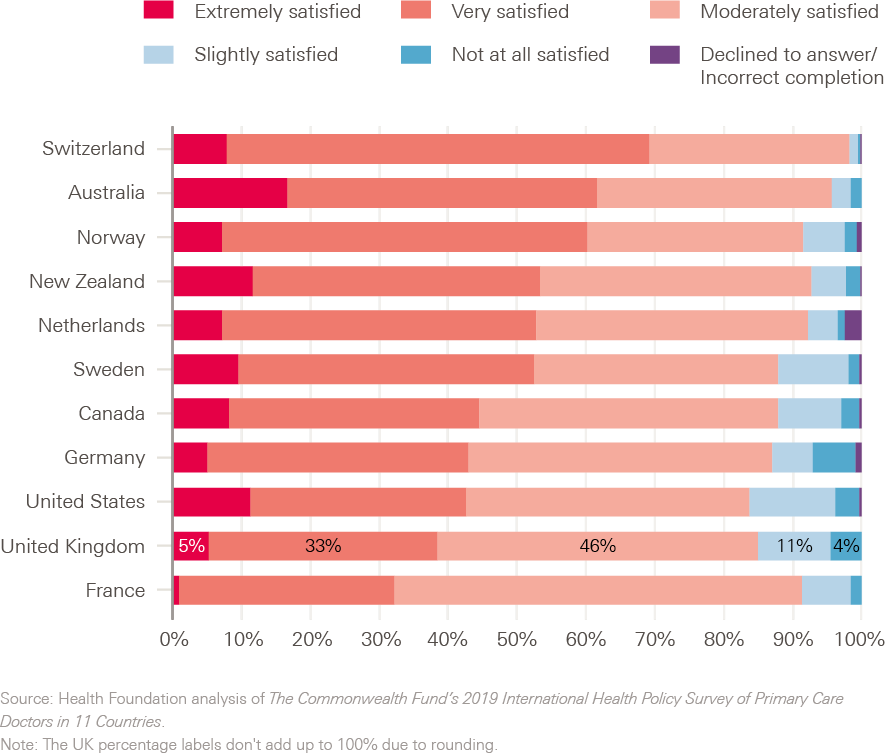

Overall satisfaction with practising medicine

GP satisfaction in the UK is low compared to other countries. 39% of surveyed UK GPs report feeling ‘extremely or very satisfied’ with practising medicine, compared to an average of 51% for the 10 other countries in the survey (Figure 1). Only France has lower overall GP satisfaction (though the proportion of GPs reporting that they are ‘not at all satisfied’ or only ‘slightly satisfied’ is higher in the UK).

Figure 1: Overall how satisfied are you with practising medicine?

Workload

GP workload includes time spent with patients, but a significant proportion of the work that GPs do happens outside consultations. This includes writing referral letters, managing prescription requests, and liaising with housing authorities, social services, food banks and other services. In this survey, 6% of GPs in the UK report feeling ‘extremely satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their overall workload – the lowest of any country surveyed.

Time with patients

In addition to overall workload, the survey asks how GPs feel about the amount of time they are able to spend with patients. Only 5% of UK respondents feel ‘extremely satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the amount of time that they spend with patients – significantly lower than the satisfaction reported by GPs in the other 10 countries surveyed. The UK is also an outlier in terms of short appointments: 86% of GPs in the UK report that average appointments involved less than 15 minutes of face-to-face time with patients – the highest percentage of all countries featured in the survey. 77% of GPs in the UK report that their average appointment length for a routine appointment is 10 minutes or less.

Satisfaction with pay

UK GPs report lower satisfaction with pay than any of their international counterparts. There was some regional variation within the UK: 37% of GPs in Northern Ireland report that they are ‘extremely or very satisfied’ with pay, compared with 25% in England. (33% of GPs in Scotland and 29% in Wales say they are ‘extremely’ or ‘very satisfied’, but the differences are not statistically significant between these and other UK nations.)

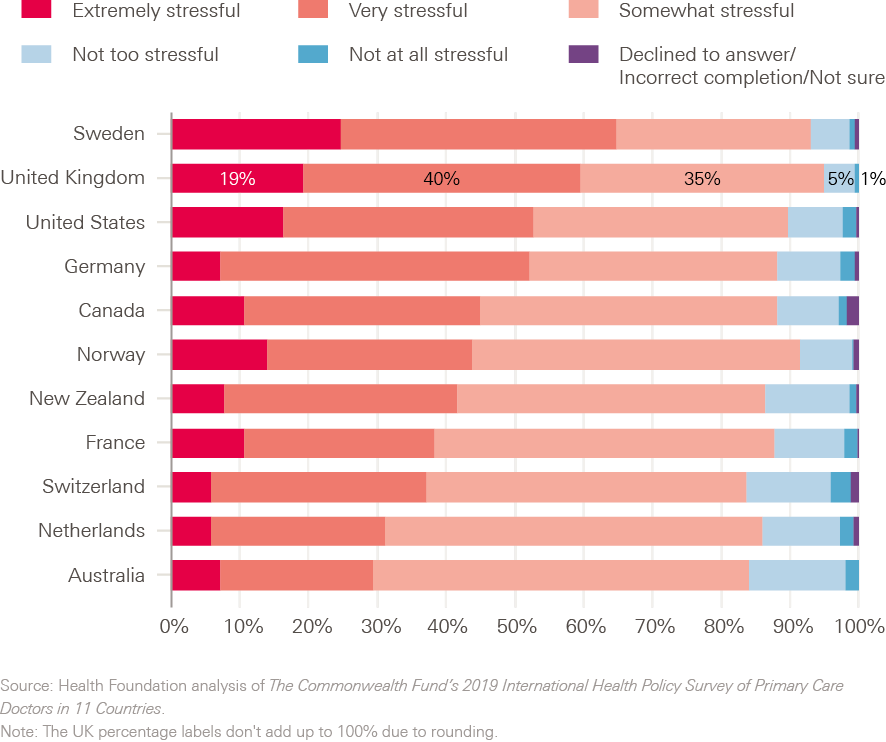

Stress levels

High workload and short consultation times are likely factors affecting the number of GPs finding their work stressful. 60% of UK respondents report that they find practising in primary care to be ‘very stressful’ or ‘extremely stressful’ (Figure 2). This is similar to the 59% responding the same way in the 2015 Commonwealth Fund survey, suggesting that little progress has been made in reducing GP stress. Reported stress levels vary across the UK. In England 62% of GPs said they are ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ stressed, compared with 52% in Wales, 48% in Scotland and 43% in Northern Ireland.

Figure 2: How stressful is your job as a GP?

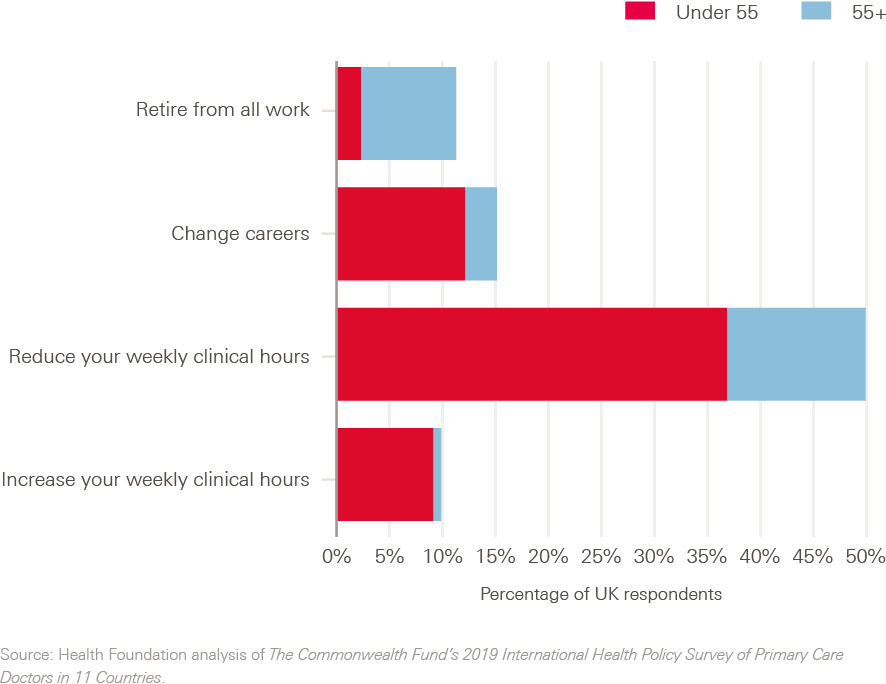

Future career plans

Retaining the existing workforce is an important component of efforts to increase GP numbers across the UK, but data from this survey suggest doing so will be difficult. In 2019, 70% of UK GPs report that they work full time (35 or more hours a week), down from 80% in the 2015 survey. 49% of GPs surveyed plan to reduce their weekly clinical hours in the next 3 years (compared to 10% who plan to increase them). The percentage of UK GPs who plan to retire in the next 3 years has reduced – from 17% in the 2015 survey to 11% in 2019. But the number of GPs planning to change career has risen (15% in 2019 compared to 8% in 2015).

Figure 3 shows that it is not only people aged 55+ who are planning to leave general practice or reduce their clinical hours: 21% of those planning to retire from all work, 81% of those planning to change careers and 74% of those planning to reduce their weekly clinical hours are aged under 55.

Figure 3: In the next 1 to 3 years do you plan to…?

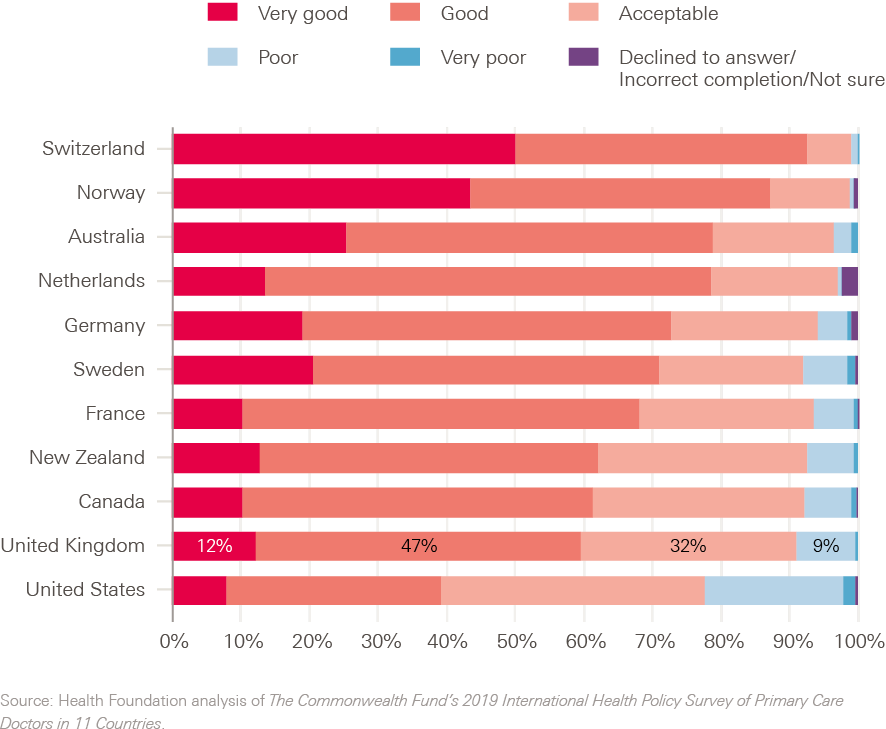

Do GPs think they’re providing good care?

The 2019 survey asked GPs to consider the quality of care they provide to patients. In response to a question only asked to UK GPs, 27% feel that the quality of care they provide to patients in general practice has improved in the last 3 years (either ‘a lot’ or ‘somewhat’). This compares with 31% who feel that the care they provide has worsened.

When asked to consider the overall performance of the NHS, 60% of GPs in the UK state that it is ‘good’ or ‘very good’, while 9% feel that it is ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’. This is similar to Canada (61% believe their health system is good/very good) and New Zealand (62%). Only GPs in the US rate their system lower (Figure 4). Within the UK, GPs in Northern Ireland are particularly likely to hold their health system in low regard – just 39% agreeing that it is ‘good’ or ‘very good’, significantly different from 60% in England. GPs in the UK are also not optimistic about the trajectory of NHS performance. 18% think performance has improved in the past 3 years, while 46% feel it has declined.

Figure 4: How would you rate the overall performance of the health care system in your country?

† However, the UK’s result was not significantly different from Germany (9%), Norway or Sweden (8%).

‡ However, the UK’s result was not significantly different from Germany (83%) or The Netherlands (85%).

§ Difference with Wales is not statistically significant compared with England, though there is a statistically significant difference between England and Scotland and England and Northern Ireland.

What care are GPs providing and how is it changing?

Consultation type

As demand for appointments rises, policymakers have been looking for ways to reduce GP workload. This includes using online and digital technology to access primary care services – referred to as ‘digital first primary care’ – which NHS England argues will increase patient convenience and allow practices to better manage their workload. Data from the Commonwealth Fund survey shows how GPs are currently working, how this is changing, and to what extent GPs may be prepared to adopt different ways of working in the future.

A range of consultation types have evolved in recent years – including telephone triage (to identify the type of care required), telephone consultations and e-consultations – in addition to the more traditional face-to-face appointments.

Data from this survey indicate that instead of replacing one consultation type with another (for example, using telephone consulting to deal more efficiently with a problem that might previously have used a face-to-face appointment), GPs in the UK are spending more time on many types of consultation (Figure 5). 44% of UK GPs say that the amount of time they spend doing face-to-face consultations has increased in the last 12 months, compared with the 6% who feel it has reduced. Increases in the amount of time spent doing telephone triage and telephone consultations are even more pronounced. 62% say they spend more time on telephone triage and 71% say they spend more time on telephone consulting.

Figure 5: In the past 12 months, how, if at all, has the amount of time you spend doing the following patient care activities changed?

Newer consultation types – email and video consultation – are either not offered or not increasing as fast. Only 21% of GPs surveyed in the UK currently offer email consultations, and even fewer (just 11%) currently offer video consulting.

Use of information technology within general practice

Information technology, or the use of computerised systems within general practice, comprises a broad set of functions. It includes an electronic medical record (EMR – for electronic prescribing, search and audit functions), systems to allow lab results and hospital correspondence to be received and processed electronically, and systems for alerts to help improve patient safety. It also includes patient-facing services, for example online prescription requests, appointment booking and e-consultations.

In previous surveys by the Commonwealth Fund, UK general practice has tended to be more advanced in the use of information technology than other countries. In 2006, 89% of UK GPs reported routinely using an EMR, rising to 98% by the 2015 Commonwealth Fund Survey. In the 2019 edition, 99% of UK respondents say that they routinely use EMRs. Five other countries surveyed have almost total use of EMRs. In Canada, France, Germany and the United States usage of EMRs is between 86-91%, and in Switzerland coverage is 70%.

Although EMRs are in use across the UK, there is variation in the wider use of information technology within UK general practice. The small number of GPs interviewed for the survey in some countries (see Appendix) means that there is a danger of drawing too much from data, but the variation between some regions is large. For example, 97% of GPs surveyed from London (and 95% for the rest of England) say that patients are able to book appointments online, compared to 45% in Northern Ireland, a statistically significant difference. (In Wales it is 80% and Scotland 64%, both of which are significantly different from Northern Ireland.)

GPs in the UK are using computerised systems for a relatively wide range of tasks compared to GPs in other countries (Table 1). GPs in the UK are the most likely to receive computerised reminders for guideline-based interventions and/or screening tests – 72% say that they do, though this is down from 78% in the 2015 survey. The vast majority of UK GPs (91%) also use computerised systems to send patients reminder notices – for example, for flu vaccines or diabetic checks. The percentage of UK GPs using computerised systems to order and track laboratory results has increased since the 2015 survey (84% in 2019, compared with 72% in 2015). Conversely, 56% receive an alert or prompt to provide patients with test results, down from 65% in 2015.

Table 1: How computerised systems are used in general practice – UK ranking shown in parentheses

|

Are the following tasks routinely performed in your practice using a computerised system? |

||

|

2015 |

2019 |

|

|

Patients are sent reminder notices when it is time for regular preventive or follow-up care (eg, flu vaccine or HbA1c for diabetic patients) |

90% (2nd) |

91% (2nd) |

|

All laboratory tests ordered are tracked until results reach clinicians |

72% (1st) |

84% (2nd) |

|

You receive an alert or prompt to provide patients with test results |

65% (1st) |

56% (3rd) |

|

You receive a reminder for guideline-based interventions and/or screening tests |

78% (1st) |

72% (1st) |

Note: statistically significant year-on-year changes are indicated in bold.

When directly patient-facing aspects of care are considered, the position of UK GPs relative to other countries is more variable (Table 2). 90% of UK GPs say that they offer online appointment booking – the highest of any country surveyed – and 91% say that they offer online repeat prescription requests. However, only 60% of GPs offer their patients the option to communicate with their practice via email or a secure website regarding a medical question or concern – ranking 7th out of 11 internationally. There is also room for improvement in relation to offering patients the option to view test results online (52%).

Table 2: Online services available to patients

|

Does your practice offer your patients the option to… |

|

|

Yes % (rank) |

|

|

Communicate with your practice via email or a secure website about a medical question or concern? |

60% (7th) |

|

Request appointments online? |

90% (1st) |

|

Request refills for prescriptions online? |

91% (2nd) |

|

View test results online? |

52% (4th) |

Use of performance and quality data

Having access to performance data and analysing those data to improve care is an essential function of a high-performing health system. The survey asked GPs how often their practice receives and reviews data on a range of aspects of patient care.

GPs in the UK lead the pack in terms of receiving and reviewing performance data (Table 3). Compared to their international counterparts, UK GPs are more likely to receive and review data on a yearly or quarterly basis on hospital admissions or emergency department use, prescribing practice, patient satisfaction and patient reported outcomes. However, more progress can be made. While the UK ranks first internationally on the use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), only 63% of UK GPs state that their practice receives and reviews PROMs on a quarterly or annual basis.

Table 3: Use of quality and performance data by GPs

|

How often, if at all, does your practice receive and review data on the following aspects of your patients' care? |

|

|

Quarterly or annual % (rank) |

|

|

Clinical outcomes such as percentage of diabetics or asthmatics with good control |

89% (2nd) |

|

Patients' hospital admissions or emergency department use |

80% (1st) |

|

Prescribing practice (eg use of generic drugs, antibiotics or opioids) |

91% (1st) |

|

Surveys of patient satisfaction and experiences with care |

79% (1st) |

|

Surveys of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) |

63% (1st) |

Communication between GPs and other providers

The survey provides insight into whether some core components of care integration – such as the sharing of patient information to deliver safe care – are happening.

The UK performs well compared to other countries in terms of communication between GPs and acute providers, but there is still room for improvement. Basic communication between specialist and primary care does not always take place – and, when it does, this communication is not always timely. 69% of GPs in the UK say that they ‘usually’ (defined by the survey as 75–100% of the time) receive information from a specialist about changes made to the patient medication or care plan, while 96% say that they ‘usually’ or ‘often’ (defined by the survey as 50–100% of the time) receive this information. Although patients frequently require medication changes after specialist review (and patients may expect GPs to ‘know’ the outcome of their review), only 8% of GPs report that they ‘usually’ receive a report within a week and only 26% ‘usually’ or ‘often’ receive a report within a week (the lowest performance of any country surveyed).

The UK performs relatively well for GPs receiving notification when patients access emergency care. Table 4 shows that the majority of GPs ‘usually’ or ‘often’ receive notification when their patients are seen in after-hours care, an emergency department or are admitted to hospital, but – again – this information often has a time lag. Only 23% of surveyed UK GPs report that they receive the information they need to continue managing the patient within 48 hours of discharge. Within the UK, GPs in Scotland appear to have the fastest access to information from hospital specialists after an admission. 53% of GPs surveyed in Scotland say that they receive the information they need to continue to manage the patient within 48 hours of discharge from hospital. This statistically significant difference compares with an average of 20% within 48 hours in England, 18% in Wales, and 9% in Northern Ireland.

Table 4: Communication between GP practices and hospital services

|

When your patients have been referred to a specialist, how often do you… |

|

|

Usually/Often % (rank) |

|

|

Receive from the specialist information about changes made to the patient medication or care plan? |

96% (3rd) |

|

Receive a report with the results of the specialist visit within 1 week of service? |

26% (11th) |

|

How often do you receive notifications that your patients have been… |

|

|

Usually/Often % (rank) |

|

|

Seen for after-hours care? |

96% (2nd) |

|

Seen in an emergency department? |

91% (3rd) |

|

Admitted to a hospital? |

86% (3rd) |

|

Less than 48 hours % (rank) |

|

|

After your patients have been discharged from the hospital, how long does it take, on average, before you receive the information you need to continue managing the patient, including recommended follow-up care? |

23% (7th) |

Note: Usually/Often is defined by the survey as 50–100% of the time.

How prepared is general practice for multidisciplinary primary care?

As set out in Box 2, all countries in the UK have embarked on reforms (albeit at different speeds of implementation) in which GPs lead a broader primary care team, including additional health professionals (such as pharmacists and physiotherapists) and non-medical professionals (such as social prescribing link workers). The four countries share an intention to improve connections between general practice and other services, including social care and other sources of non-medical support to address patients’ social needs.

Data from this survey give an indication of the extent to which GPs in the UK are already working with some of the roles being introduced as part of wider teams:

- 73% have at least one pharmacist working on their team.

- 26% have at least one physiotherapist working on their team.

- 13% have at least one physician associate working on their team.

Although the precise job description of these roles may vary across international boundaries, the data suggest that other countries have made more progress in some areas. For example, 96% of GPs in the Netherlands and 97% in Germany report that they already work with physician associates. Learning from their experience may be valuable.

Caring for patients with chronic conditions

Meeting the needs of growing numbers of people living with chronic conditions is one of the biggest challenges facing the NHS. The responsibility for providing much of this care, including new models of coordinated care and disease management, falls on primary care.,

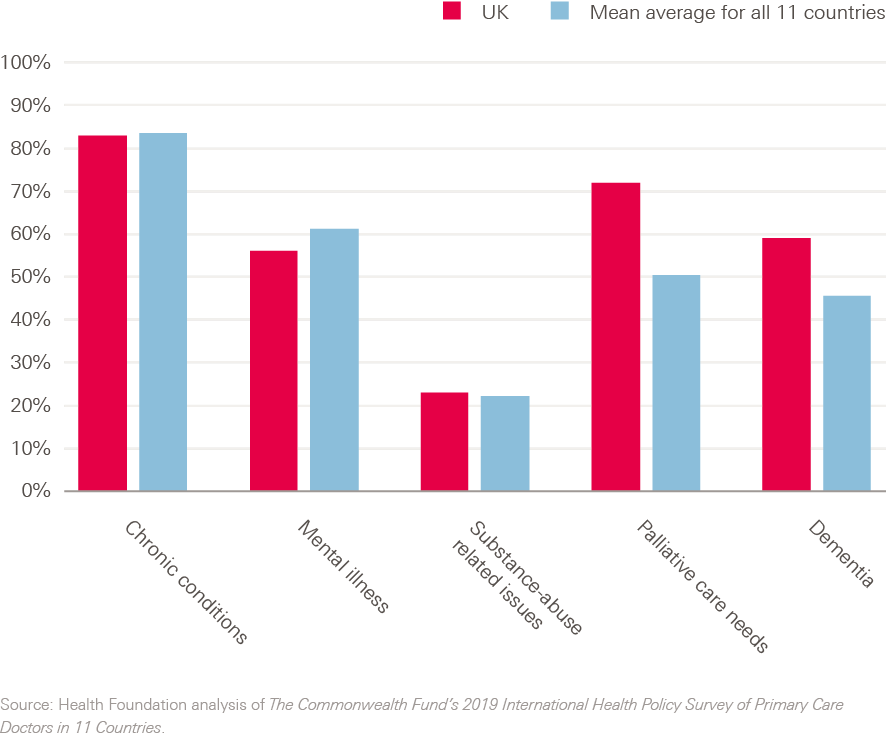

83% of GPs in the UK report that their practice is well prepared to provide care for patients with chronic conditions (Figure 6) – though this still leaves 17% of GP respondents not feeling well prepared to do so.

Relative to their international counterparts, UK GPs report feeling well prepared to provide care for patients with dementia or palliative care needs (59% and 72% respectively). GPs feel that their practices are less prepared to provide care for patients with substance misuse or mental illness (23% and 56% respectively stated that they are well prepared, which is in line with responses from other countries).

Figure 6: How well prepared is your practice to manage care for the following patients?

The long-standing ambition in all four UK countries to improve integration between primary care and other kinds of care is supported by UK GPs: 73% chose ‘better integration of primary care with hospitals, mental health, and community-based social services’ as a top priority to improve quality of care and patient access. Only Sweden (76%) has a similar or higher level of support for this.

However, integration of services in practice is challenging. The survey asked about coordination between GPs and ‘social services’, which is likely to mean different things to GPs in different countries. In the UK, this may include adult social care providers, as well as wider services available in the community via a range of voluntary and community sector providers. 61% of respondents from the UK feel that a lack of follow-up from social service organisations about which services patients received or need poses a major challenge in coordinating their patients’ care. Around half feel that major challenges to address include inadequate staffing to make referrals and coordinate care with social service organisations (56%), too much paperwork regarding coordination with social services (50%) and lack of awareness of social service organisations in the community (47%). One in three UK GPs (34%) feel that the lack of referral system or mechanism to make referrals is a major challenge.

Integration with other non-medical services

Linking patients with a much broader set of services that impact on their health, such as housing or other kinds of social support, is seen as an increasingly important function of general practice. Doing this requires GPs to be aware of the non-medical needs that their patients might be experiencing, which may be achieved through some sort of screening process. This survey indicates that the screening of patients in UK general practice for social needs is variable (Figure 7). Compared to other countries, the UK performs highly for screening patients for problems with housing, domestic violence and social isolation or loneliness, but poorly for screening financial security and transport needs.

In all countries, the survey results suggest that many patients are not being assessed for social needs related to their health. The percentages in Figure 7 show the proportion of respondents from each country stating that they screen for each need usually, often or sometimes, which translates as 25% or greater of the time. Even when percentages are high, there are likely to be many patients that are not being screened for these social needs. The survey did not ask GPs what happens after patients are screened for social needs and how that information is used.

Figure 7: The proportion of respondents who screen or assess for each specified social need usually, often or sometimes

¶ The survey question asked about physician assistants, but we assume that the GPs who responded to this survey from the UK would respond to this question considering physician assistants to be the same as physician associates.

Discussion

Health systems in high-income countries face several common challenges, including caring for growing numbers of people with multimorbidity and tackling persistent inequalities in health. International comparisons can help identify opportunities for learning about how to address these challenges, but they should also be treated with some caution. Definitions can vary between countries (for example, what counts as social services), and the data need to be interpreted within the wider historical and policy contexts of the systems being compared.

Nevertheless, surveys like this offer broad signals for policymakers. Overall, the findings present a mixed picture for general practice in the UK. In some aspects of care – particularly compared to countries with weaker primary care systems, like the US, the UK is an international leader. Almost all GPs surveyed in the UK use electronic medical records, and the use of data to review and improve care is relatively high. GPs in the UK are broadly supportive of ambitions to improve integration of services. Yet the survey also highlights several areas of major concern, including low GP satisfaction and high stress levels. GPs are more likely to think that the quality of care that they – and the wider NHS – are able to provide is declining than to feel that it is improving.

The remainder of this discussion focusses on England, where reforms to primary care have been proceeding at pace since the publication of the NHS Long term plan in 2019. The plan promised an additional £4.5bn investment in primary and community care by 2023/24 and offered a vision of neighbouring GPs working together in new PCNs, leading expanded teams of pharmacists, physiotherapists and other allied health professionals. PCNs are expected to offer more preventative care with better links to community, social care and a broad range of other non-medical services. The plan also described ambitions for ‘digital first’ primary care, where all patients would have the right to video consultations by April 2021. The survey data highlight several challenges for these reform efforts in England.

Workforce pressures risk undermining primary care reform

The survey illustrates fragility in the foundations of which PCNs are being built. England has the lowest proportion of GPs feeling satisfied with their workload compared to the other 10 countries, and the second highest ranking of GPs reporting very high or extreme levels of stress. These perceptions are not surprising: the most comprehensive analysis of GP workload to date found that overall workload had increased by 16% between 2007–2014 and will have risen further since. Adjusted for inflation, average income has also declined between 2008 and 2017 for both salaried and partner GPs. Stress caused by high workloads has been a persistent feature of large-scale GP surveys and stress has been linked to burnout and increased concern about patient safety. The survey’s finding of low satisfaction among GPs with the short appointments they can offer patients – and the UK’s ranking as the country with the shortest appointments – will not be helping.

There is a close relationship between these pressures and GP retention. There was a slight drop between the 2015 and 2019 surveys in the proportion of GPs in the UK reporting that they plan to retire in the next 3 years (from 17% to 11%), but nearly half (including younger GPs) plan to reduce their clinical hours. Again, these findings are consistent with other studies. A 2019 study found that 18% of GPs surveyed planned to leave or retire within the next 2 years, and 48.5% planned to do so within the next 5 years. Work intensity and workload were cited as the most common reasons behind their intention to leave.

These challenges are not new. Workload has been climbing steadily in general practice for years. The result is that more GPs are leaving the profession or reducing their hours than are being recruited or increasing their hours. Full-time equivalent GP numbers are falling. And the number of FTE GPs has been falling fastest in the most deprived areas, where health needs are greatest. This is despite a raft of policy measures implemented since 2015 to try to meet a government pledge to recruit an additional 5,000 GPs by 2020. There have also been efforts to try to retain more GPs and to help manage escalating workload – including an improved ‘induction and refresher’ scheme for fully qualified GPs returning to practice after a break, increased funding for general practice, and additional allied health professionals in the primary care workforce.

The 2015 survey showed that GPs in the UK were the most stressed of the 11 countries surveyed. What is most concerning about the 2019 results (see Figure 2) is that high stress levels, low satisfaction with practising medicine and high expressed intention to leave general practice have all persisted despite actions taken to address them. This suggests that current policy approaches are inadequate, insufficient, or both.

Workload is increasing across consultation types

Part of the policy response to challenges in recruiting and retaining GPs has been to try to identify new ways of reducing pressure on GP workloads – including by boosting the use of digital technology in primary care. Use of online consultations and other digital tools is seen by NHS England and other policymakers as potential alternatives to face-to-face appointments.

In this Commonwealth Fund 2019 survey, GPs report spending more time on all main consultation types in general practice (telephone triage, telephone consulting and face-to-face consulting). Any potential substitution effect between consultation types (for example, telephone triage saving the need for face-to-face appointments) appears to be eclipsed by increased demand for services.

The survey also suggests that the proportion of GPs using new forms of consultation – video and email – is small. This suggests that it may be difficult to deliver NHS England’s promise to extend the right for all patients to have video consultations by April 2021. Research on GPs’ use of video consultations is limited, but evidence suggests there are many questions to resolve and potential unintended consequences – from whether the WiFi infrastructure exists to allow good quality connections between GPs and patients, to what impact video consultations have on GP workload and the distribution of uptake between patient groups. Some new forms of digital first primary care have been evaluated (but in populations that are unrepresentative of those using general practice), but it remains an open question whether new technology can help with the most urgent challenges facing GPs and their patients.

In other areas, use of technology among UK GPs is advanced. The survey confirms previous findings about the long-established use of IT systems within general practices for electronic health records, sending reminders to patients and clinicians, and for UK patients to book appointments online (even if appointments are in short supply). The IT capacity for hospitals and other health and care providers to communicate promptly with general practice has taken much longer to evolve, and information can be slow in arriving.

Support and evaluation are needed as primary care teams evolve

Delivering on the commitments in the NHS Long term plan requires GPs to work with other health and care professionals in multidisciplinary teams, and connect patients with non-medical services in their community. These are core aspects of the new primary care network contract proposed by NHS England. The aim is to provide more coordinated services, boost preventative care and make the best use of the wider primary care team.

The 2019 survey indicates that GPs are familiar with working with pharmacists, but the number of GPs or practices with experience of working with physician associates and first contact physiotherapists is lower. Providing ways to help PCNs fulfil the potential of these additional roles – for example, through sharing of best practice examples, or guidance from professional bodies such as the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy – will be important.

The new PCN contract also includes funding for general practices to hire social prescribing link workers – and it is hoped that every PCN will hire at least one. Social prescribing is an approach to connecting patients with non-medical services to improve their health – for example, helping patients access support related to address housing or social isolation. While a greater focus on addressing patients’ social needs is welcome, evidence on the impact of social prescribing is limited., Social prescribing can only ‘work’ if services are available in the community to address patients’ non-medical needs. And these interventions come with potential unintended consequences – including medicalising people’s social issues and exacerbating inequalities. Data from this survey suggest that screening for social need in general practice is currently variable. Evaluation is needed to understand what approaches to social prescribing work, for which patients and in what contexts.

Recommendations for policy

These findings highlight several considerations for national policy in England:

- Enable all GPs to offer longer appointment times. This is particularly difficult in the face of rising patient need and falling GP numbers; however, GPs with longer appointment times report greater job satisfaction. Offering longer appointments may paradoxically increase efficiency by improving the quality of care delivered, therefore reducing the need for more frequent shorter appointments. Policymakers hope that the additional roles recruited to PCNs may free up GP time, but it is not yet clear whether this will be the case. In reality, freeing up enough additional capacity to offer longer GP appointments will be challenging without more GPs.

- Do more to understand what would keep GPs in practice – and rapidly implement solutions. This survey suggests that measures tried so far are not turning the tide on GPs’ intentions to reduce their hours or leave practice altogether. Increasing the number of allied health professionals in primary care is not a substitution for GPs. Intensifying efforts to understand what would keep UK GPs in practice will be key to improving retention. This survey demonstrates that GPs in the UK are less likely than their international counterparts to report satisfaction with pay and with workload.

- Improve the speed of communication with hospitals. No single country has optimised use of electronic records, or ‘solved’ the challenge of care coordination. Although the UK performs reasonably well with regard to the sharing of clinical information between practices and hospitals, GPs report that these processes are often too slow. This may have implications for the quality of clinical care GPs can deliver. The UK has ambitious digital first primary care strategies, but must ensure that the basics are in place too.

- Set realistic ambitions for digitally enabled primary care. This survey suggests that most GPs in the UK are a long way from meeting ambitious targets to offer digital services to patients. At a time when GPs are under significant and sustained pressure, policymakers must consider whether the evidence of benefit is sufficient to justify pushing this agenda, and should thoroughly evaluate the impact of digital first models to ensure that they deliver the intended benefits to patients and staff.

Conclusion

General practice in the UK has many strengths – chief among them, its roots in a universal health care system which is free at the point of delivery, and the longstanding relationships built up with families and communities that are essential to good care. Compared to some of the countries included in this study, general practice in the UK performs well in several key areas.

However, data from the survey should add to the growing chorus of alarm bells for policymakers. After a decade of austerity in NHS funding and cuts in wider services that impact on health, general practice in the UK has never looked more vulnerable. Policies to improve and reform primary care services – including PCNs – must reflect the context in which they will be implemented. Solutions to pressures in general practice that rely on the existing GP workforce doing more are likely to misfire.

References

- Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Shah A, Schneider EC. Primary Care Physicians’ Role In Coordinating Medical And Health-Related Social Needs In Eleven Countries: Results from a 2019 survey of primary care physicians in eleven high-income countries about their ability to coordinate patients’ medical care and with social service providers. Health Affairs. 2019; 10.1377/hlthaff. 2019.01088.

- Martin S, Davies E, Gershlick B. Under Pressure: What the Commonwealth Fund’s 2015 international survey of general practitioners means for the UK. The Health Foundation; 2016.

- Office for National Statistics. Overview of the UK population: August 2019. ONS; 2019.

- Palmer, B. Is the number of GPs falling across the UK? [blog]. Nuffield Trust; 2019 (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/is-the-number-of-gps-falling-across-the-uk).

- NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan 2019. NHS; 2019 (www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/).

- Buchan J, Gershlick B, Charlesworth A and Seccombe I. Falling short: the NHS workforce challenge. The Health Foundation; 2019.

- Owen K, Hopkins T, Shortland T, Dale J. GP retention in the UK: a worsening crisis. Findings from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(2):e026048.

- Royal College of General Practitioners Northern Ireland. Support, Sustain, Renew: a vision for general practice in Northern Ireland. RCGPNI; 2019.

- Royal College of General Practitioners Scotland. From the Frontline: The changing landscape of Scottish general practice. RCGPS; 2019.

- Information Services Division. Primary Care Workforce Survey Scotland 2017. NHS National Services Scotland; 2018.

- Royal College of General Practitioners Wales. Transforming general practice: Building a profession fit for the future. RCGPW; 2018.

- Statistics for Wales. GPs in Wales, as at 30 September 2018. Welsh Government; 2018 (https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-03/general-medical-practitioners-as-at-30-september-2018-354_0.pdf).

- Ipsos MORI. GP patient survey 2019. NHS England; 2019 (https://gp-patient.co.uk/about).

- Department of Health Northern Ireland. Health and Wellbeing 2026: Delivering together. DoHNI; 2016

- Department of Health Northern Ireland. Health and Wellbeing 2026: Delivering together. Progress report May 2019. DoHNI; 2019.

- Scottish Government. Healthier Scotland: Health and Social Care Delivery Plan, December 2016. Scottish Government; 2016.

- Burgess L. Primary Care in Scotland (SPICe Briefing paper). The Scottish Parliament; 2019.

- National Primary Care Board. Strategic Programme for Primary Care. Welsh Government; 2018.

- Welsh Government. A Healthier Wales: Our Plan for Health and Social Care. Welsh Government; 2019.

- NHS England and the British Medical Association. Investment and evolution: A five-year framework for GP contract reform to implement The NHS Long Term Plan 2019.

- The Commonwealth Fund. 2006 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians. The Commonwealth Fund; 2006 (www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2006/nov/2006-international-health-policy-survey-primary-care-physicians).

- Stafford M, Steventon A, Thorlby R, Fisher R, Turton C, Deeny S. Briefing: Understanding the health care needs of people with multiple health conditions. The Health Foundation; 2018.

- Salisbury C, Man M-S, Bower P, Guthrie B, Chaplin K, Gaunt DM, et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: a pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. The Lancet. 2018; 392(10141):41–50.

- Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, Slewa J, Chen W, Tian D, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Family Practice. 2018; 19(1):11.

- Hobbs FR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, Stevens S, Perera-Salazar R, Holt T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. The Lancet. 2016; 387(10035):2323–30.

- Atkins R, Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S, Checkland K. Trends in GP incomes in England, 2008–2017: a retrospective analysis of repeated postal surveys. British Journal of General Practice. 2020; 70(690):e64–e70.

- Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S, Checkland K. Ninth National GP Worklife Survey. Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System; 2017 (http://blogs.lshtm.ac.uk/prucomm/files/2018/05/Ninth-National-GP-Worklife-Survey.pdf).

- Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, O’Connor DB. Association of GP wellbeing and burnout with patient safety in UK primary care: a cross-sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice. 2019: bjgp19X702713.

- Bostock N. GP workforce falling 50% faster in deprived areas, official data show GPonline; 23 May 2018 (www.gponline.com/gp-workforce-falling-50-faster-deprived-areas-official-data-show/article/1465701).

- NHS England. General Practice Forward View April 2016. NHS England; 2016.

- Hammersley V, Donaghy E, Parker R, McNeilly H, Atherton H, Bikker A, et al. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: a non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2019; 69(686):e595-e604.

- Ipsos MORI and York Health Economics Consortium with Salisbury, C. Evaluation of Babylon GP at hand. NHS Hammersmith and Fulham CCG and NHS England; 2019.

- Clarke G, Keith J, Steventon A. The current Babylon GP at Hand model will not work for everyone [blog]. The Health Foundation; 2019 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/the-current-babylon-gp-at-hand-model-will-not-work-for-everyone).

- Drinkwater C, Wildman J, Moffatt S. Social prescribing. BMJ. 2019; 364:l1285.

- Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, Farley K, Wright K. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(4):e013384.

- Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017; 53(5):719-29.

- Alderwick HA, Gottlieb LM, Fichtenberg CM, Adler NE. Social prescribing in the US and England: emerging interventions to address patients’ social needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018; 54(5):715-8.

- De Marchis EH, Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Do patients want help addressing social risks? Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. Forthcoming.

Appendix: Further details on method

Response rate

The overall response rate was 26.8% (n=1,001). During fieldwork, an interviewer error in the UK resulted in the CATI (telephone methodology software) link being sent to web (self-administered) respondents. After reviewing the data, N=403 cases were removed from the data due to this error. If the correct link had been sent, the response rate would have been 37.6%.

Weighting

For the 11 country results, data from each country were weighted to ensure the final outcome was representative of GPs in that country based on their demographics (gender, age – and region for the UK) and selected specialty types.

This procedure also accounted for the sample design and probability of selection as needed, as well as differential non-response across known population parameters.

To create all England totals, the total number of respondents weighted for London and England (excluding London) were used to ensure the final outcome was representative of the number of London GPs versus rest of England GPs.

When creating an all respondent total (all 11 countries) or all other 10 countries total (to show in comparison to the UK result), the mean average percentage of the 10 or 11 percentages was calculated.

Uncertainty and limitations

Many of the survey results provide comparisons between countries. The weight-adjusted margin of error (for a 95% confidence level) varies between the 11 countries from 2.0% (Sweden) to 4.6% (Australia). For the UK as a whole it is 3.5%. This includes the ‘design effect’ (error introduced due to the weighting procedure).

This report includes a small number of sub-analyses between the different countries of the UK, and within different subgroups of respondents. Not all the results of these sub-analyses are significant at the 95% level, but we have included them as they may be of interest as part of a wider trend, and stated when they are not significant.

The margin of error (for a 95% confidence level) varies significantly between the different countries of the UK and it is important to bear this in mind when interpreting the findings. The margins of error for the five UK regions are:

- England excluding London (475 respondents): 4.5%

- London (200): 7.0%

- Scotland (135): 8.5%

- Wales (111): 9.3%

- Northern Ireland (80): 11.0%

These are the theoretical margins of error if the percentage of respondents giving a certain answer is exactly 50%, where margins of error will be highest. They therefore give some indication of where particular caution should be taken with results. A margin of error is a relationship between sample size and the percentage of respondents giving a certain answer: it does not take into account how the survey was conducted.

Sampling error is only one type of error that affects survey outcomes. Other forms of error that are common to all surveys include selection bias (due to the respondents not being representative, and the weighting failing to fully address this) and questionnaire effects (such as questions being unclear or understood differently).

** The margin of error is one side of a confidence interval. So a margin of error of 3.5% for a 95% confidence level means that if the survey were conducted 100 times, you would expect the data to be within 3.5 percentage points above or below the percentage reported in 95 of the 100 surveys.