Acknowledgements

We would like to thank David Dixon, Wendy Lewis and Andrew Wilson for their contributions to this report, and Tom Downes, Ruth Glassborow, Andrew McLaughlin, Christine Owen, Zoe Radnor and Sharon Williams for their helpful comments on earlier drafts.

We would also like to thank colleagues at the Health Foundation and the Advancing Quality Alliance (AQuA) for their support, guidance and patience during the research, drafting and production of this report.

About this joint publication

Improving flow on a whole system basis is a field in which the Health Foundation and the Advancing Quality Alliance (AQuA) – an NHS quality improvement organisation – have a long-standing interest.

Over the past decade, the Health Foundation has supported a number of large-scale programmes aimed at improving the reliability and quality of clinical systems.,

One of the key sources for this report is the learning from one of these – the Flow Cost Quality programme – which set out to improve patient flow along the urgent and emergency pathway in two NHS foundation trusts in England., This programme has had a significant and sustained impact on service and patient outcomes, and has gained national recognition., To support other organisations seeking to make large-scale change, in 2015 the Health Foundation published a report, Constructive comfort.

This identifies a series of success factors that need to be in place for change to happen, and describes the steps that national bodies need to take to create the right conditions for change.

AQuA, meanwhile, has extensive experience in supporting and enabling change on a system-wide basis over the past six years. AQuA has worked with health and social care system leaders across the UK to design and implement new models of care based on a common vision focused on the needs and ambitions of each community. In early 2016, AQuA conducted a 90-day rapid review into whole system flow. The review sought out case examples from health care systems in the UK and internationally, considered the available evidence base and gained insights from other industry sectors. This report reflects AQuA’s learning from the review, and its work in supporting systems to build the capability to plan, deliver and sustain change.

As well as drawing on existing expertise and knowledge the Health Foundation and AQuA have gained from supporting system-wide change, this report is informed by a series of discussions and workshops with experts in complex systems change and reviews of the published evidence. A summary of our research and engagement approach is set out in Appendix 1.

While we have drawn on learning from research and practice where it exists, many of the case studies explored in this report are at the leading edge of health care improvement practice. This work is typically at an early stage and is yet to produce measurable or independently validated results. The studies are presented here in order to provide insight into how some health and social care systems are beginning to grapple with the challenges of improving flow on a system-wide basis.

Executive summary

Improving the flow of patients, service users, information and resources within and between health and social care organisations has a crucial role to play in driving up service quality and productivity.

If every organisation in each health and social care economy were able and willing to work collaboratively to design services that optimise flow, it could lead to major improvements in patient and service user experience and outcomes.

The importance of flow is increasingly recognised by practice leaders and policymakers throughout the UK. For example, there have been recent flow improvement programmes in both Scotland and Wales. The concept of improving flow is also referenced nationally and locally, across the UK, in strategies for service configuration and for tackling emergency and elective access challenges. Where providers have been able to match capacity and demand and enable better flow between departments and organisations, there have been impressive results.

However, while there are positive examples, and while flow has become common parlance in health service management, it is important not to underestimate the scale of the challenge facing those who want to realise the full potential of flow improvement. To date, virtually all attempts to improve flow have focused on single organisations or pathways. Hardly any have sought to improve flow across the entire primary, acute and social care spectrum. The task of bridging the entrenched cultural differences between professions and bringing together organisations that have often been governed, funded, inspected and regulated in isolation has been too daunting for most.

Nonetheless, this report argues that local health and social care economies are now well placed to improve whole system flow. Not only is there now a good understanding of the methods and skills needed, but the financial logic for tackling expensive and resource-intensive bottlenecks in the flow of patients and service users between organisations is hard to resist.

The aim of this report is to provide leaders and improvement teams in local health and social care economies across the UK with a guide to the activities, methods, approaches and skills that can help to improve flow across systems. It also describes the steps that policymakers and regulators at a national level need to take to create an environment that is conducive to change on this scale.

To support this, the report sets out an integrated, multi-level organising framework. This is supported by four case studies of innovative and effective practice: the Sheffield and South Warwickshire-based Flow Cost Quality programme; the Darlington Dementia Collaborative; the ‘Wigan Deal’ for adult social care and wellbeing; and the Winona Health Transformation programme in the US.

The organising framework focuses on four distinct but interdependent levels of the system:

- Care journeys – The primary focus of any flow-related initiative should be to improve the patient and service user’s experience. It can do this through the removal of the bottlenecks, waste, delays and duplication that affect the quality of patients’ and service users’ experiences and, in many instances, the effectiveness of the care they receive. Any redesign process should also look at how to eliminate the ‘failure demand’ – demand arising from failure to provide a service or to provide it in a timely and effective fashion – that leads to people flowing into the system unnecessarily.

- The report sets out a structured approach for improving flow at the care journey level that encompasses five key areas of work:

- Creating a space for system partners to come together, build relationships, develop a sense of shared purpose and deliver co-designed solutions.

- Understanding ‘the current state’ by enabling service providers and users to work together to map the processes in each care journey and identify non-value adding activity.

- Collecting and analysing data with a view to understanding the root causes of problems and identifying potential solutions that can then be tested.

- Developing a high level ‘future state’ plan underpinned by simple guiding rules that local teams have the licence to adapt to fit their own context.

- Implementing solutions in which all parts of the system have a shared stake and responsibility, and providing opportunities for collaborative reflection and further refinement as outcomes emerge.

- Team and organisational capabilities – To improve flow successfully at the care journey level, front-line teams need to have the skills and capacity to continuously improve the quality of the care they provide. Using examples from the UK and other countries, the report describes the steps that some organisations and local health and social care economies have taken to build and sustain improvement capability.

- Local health and social care economy enablers – System leaders in each economy have a key role to play in identifying and addressing the various operational, financial, information and workforce-related issues that may support or stand in the way of effective whole system working. They also need to focus on building a learning culture in which staff, patients and service users have the capability, capacity and confidence to work together to identify problems and carry out tests of change.

- National system change levers – In what is still a highly centralised health and social care landscape, national bodies have a major influence on the ability of local economies to drive and sustain change. The report highlights the need for central regulatory, financial and performance management levers to be closely aligned with nationally driven programmes aimed at promoting whole system working, such as Sustainability and Transformation Plans in England. Ensuring that these central levers and programmes are governed by a shared understanding of how to achieve change is particularly important.

The report also emphasises the need for policymakers to give local economies the time, space and resources they need to deliver meaningful change. Finally, it argues that there needs to be a closer configuration between the practice of improvement – where the emphasis is on discovering a way towards a tailored solution through repeated tests of change – and the prevailing discourse of public sector reform, with its emphasis on the rapid development and spread of previously identified solutions.

For local health and social care economies to achieve sustained improvements in flow on a whole system basis, progress will be needed on all four of these levels. However, doing so has the potential to greatly improve the quality of care provided to patients and service users, and to make their experience of care an altogether better one.

* In this report we use the term ‘whole system flow’ to define the coordination of all processes, systems and resources, across an entire local health and social care economy, to deliver effective, efficient, person-centred care in the right setting at the right time and by the right person. There is also a glossary on pages 52-57 to provide explanations of other terms used in the report.

† In this report ‘a local health and social care economy’ refers to a geographically-defined system of health and social care organisations and services, serving a particular area.

Introduction

Improving the flow of patients and service users within and between health and social care organisations is being increasingly focused on across the UK. It is seen by both practice leaders and policymakers across the UK as having a crucial role to play in driving up service quality and productivity, as well as greatly improving the experience of care for patients and service users.,,,,,

A range of important work is currently being done in this field around the UK. For example, in England, the Emergency Care Improvement Programme is helping to improve patient flow in 40 challenged urgent and emergency care systems. NHS Improvement has entered into a five-year partnership with Virginia Mason Institute to support five NHS trusts to develop a culture of continuous improvement. And providers and commissioners in each local health and social care economy are looking at how to improve service integration and patient flow as they develop Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) and implement new models of care. Elsewhere in the UK, flow improvement programmes are being delivered in Wales – the evaluation of which is being funded by the Health Foundation – and also in Scotland.

The prize on offer is immense. If organisations are used to working collaboratively, and go out of their way to strengthen relationships and tackle the barriers to the smooth and efficient flow of patients and service users, they will be able to deliver better health and social care for their population and make better use of increasingly scarce resources. The experience for those using services would also be improved. However, there are some significant challenges that need to be overcome if the full potential of work on flow is to be realised. Chief among them is the entrenched divides between primary, acute and social care services that give rise to silo working and piecemeal, disjointed efforts to improve services.

It is critical to recognise that improving flow is as much a behavioural and relational challenge as it is a technical one. Much will hinge on the ability of local health and social care economies to foster a culture of learning that gives members of staff – working alongside patients and service users – the space, skills and permission to discover their way towards solutions to poor flow together.

As well as examining these challenges, this report sets out an organising framework, supported by case studies. The framework describes steps that can be taken to improve the flow of patients and service users, recognising this in turn requires improvements in the flow of information, equipment and staff. It provides leaders and improvement teams in local health and social care economies with a guide to the activities, methods, approaches and skills that can help to improve flow across whole systems. It also describes the steps that policymakers and regulators at a national level need to take in order to create an environment that is conducive to change on this scale.

The report consists of seven sections:

- Section 1 defines what we mean by whole system flow and explains why it is important. It also considers some of the factors that have made improving flow difficult to achieve to date. The section then describes the core components of a typical local health and social care economy and some of the techniques that can be used to understand whole system flow.

- Section 2 introduces the organising framework for improving flow across whole systems. This consists of four levels: care journeys; front-line team and organisational capabilities; health and social care economy enablers; and national system change levers.

- Sections 3-6 look in detail at each of the four levels in the framework

- Section 7 summarises the main messages from the report and provides a set of recommendations for providers, local system leaders, regional bodies and policymakers to help them take this work forward. Doing so successfully has the potential to greatly improve the quality and experience of care for patients and service users across the UK.

A note on language used in this report

Local health and social care economy: In this report ‘a local health and social care economy’ refers to a geographically-defined system of health and social care organisations and services, serving a particular area.

Whole system flow: We use the term ‘whole system flow’ to define the coordination of all processes, systems and resources, across an entire local health and social care economy, to deliver effective, efficient, person-centred care in the right setting at the right time and by the right person.

Context and definitions

What we mean by ‘whole system flow’ and why it matters

The language used by those who have an interest in improving the flow of people or resources within or between services is often technical: batching, bottlenecks, constraints and capacity management. Yet the effects of poor flow are all too readily apparent in the daily experiences of patients, service users and people working at the front line of health and social care. Stark examples of a lack of smooth flow through a system include ambulances queuing outside hospitals, crowded emergency departments, long waits on trolleys for a bed, pressures on community and social care services, overstretched GPs, and mental health patients being transferred hundreds of miles for an inpatient bed. All of this is stressful and frustrating for staff and can be devastating for patients, service users and their families and carers.

At a time when health care is under increasing financial pressure, poor flow is both a symptom and a cause of that resourcing crisis. Delays and waits are exacerbated by deficiencies in critical areas and the resulting disruption to flow leads to an ever more suboptimal use of the resources within the health and social care system.,,

Where providers have been able to match capacity and demand and enable better flow between departments and organisations, there have been impressive results.

Work supported by the Health Foundation at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust through the Flow Cost Quality programme has delivered sustained reductions in emergency care length of stay, bed occupancy and readmissions, while improving safety and the patient experience., In the US, leading high-performing providers such as the Mayo Clinic, Seattle Children’s Hospital and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital have achieved significant productivity gains and savings using flow improvement approaches (see Box 2).

Yet most flow-related initiatives to date have focused on a small segment of the patient or service user journey, usually within acute hospitals. There is a pressing need to look beyond the hospital and to give attention to every team, service and organisation that patients and service users encounter. As well as looking at services delivered within the NHS there is also a need for consideration of social care, health promotion and other local government services. Nor should the wider determinants of health (eg age, lifestyle, environment) be forgotten – or the need to tackle the gulf between physical and mental health services.

It is a lot easier to call for a whole system approach to flow than it is to deliver it. Over the past 15 years a series of UK national bodies have made strong cases for looking beyond the hospital – to look at flow from a system-wide perspective.

The most recent – but far from the first – example is NHS England’s 2015 guide for health and social care communities on delivering urgent and emergency care. This underlined the value of whole system partnerships in improving flow. A decade earlier, in 2005, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement published a guide to improving flow for system leaders, which made the point that most existing flow-related improvement work had tended to focus on single bottlenecks in the system. Future work, it said, needed to understand the flow of patients across departments, organisations and the whole system. There was also a strong emphasis on ‘whole systems working’ in many of the programmes supported by the NHS Modernisation Agency; for example, the Acute Local Improvement Partnerships, announced in 2003, used ‘a whole systems approach to follow the patient’s pathway across departmental and clinical boundaries, to deliver better care and minimise delay’. In Scotland, meanwhile, a 2007 report on patient flow in planned care made it clear that ‘the importance of getting the flow of patients right across the whole system cannot be overstated’.

Yet it has proven difficult to translate this whole system vision into reality. In Section 1.2 we consider the issues that have made it so difficult, but also describe why there are reasons to believe that change is achievable.

The challenge of achieving system-wide change

Albert Einstein once said that ‘without changing our pattern of thought, we will not be able to solve the problems we created with our current patterns of thought’. It is a quote that often crops up in articles about how to enable change in complex systems such as the NHS27 – and it does so for good reasons. Health and social care leaders and policymakers across the UK have been trying for years to cajole or nudge the various organisations and groups within their world towards a more ‘whole system’ way of working. Yet despite a succession of national initiatives – the latest in England being the Integrated Care Pioneers and New Care Models vanguard partnerships – genuine, joined-up, whole system delivery is still the exception rather than the rule.

Various elements of the system are governed, funded, inspected and regulated in silos. This reinforces significant differences, not just geographically but also culturally, between those working in hospitals and those working in community services or in primary care. As the NHS five year forward view (Forward View) stated, in relation to England, many elements of the ‘classic divide’ between ‘family doctors and hospitals, between physical and mental health, between prevention and treatment’ that characterised the NHS in 1948 remain in evidence today.

The cultural divisions between the NHS and local government are often even sharper. Local authorities are less bound by central government direction, face resource pressures even more extreme than those in health care, and are driven by the need to deliver on a local democratic mandate expressed through elected members. Across the UK there is now a greater emphasis on collaborative working between local government and the NHS. A number of new initiatives such as health and wellbeing boards and the Better Care Fund in England, and health and social care partnerships in Scotland, have been set up with this aim in mind. But while these arrangements are helping to build trust and understanding between organisations, the picture is still very patchy. In some areas, the challenge of managing potentially thorny and politically contentious processes, such as the handover of patients from acute to social care settings, exacerbates tensions between providers.

During times of financial uncertainty and risk, it is not easy to encourage people and organisations to do things differently. While some see a ‘burning platform’ and are galvanised into collaborative action, others respond to the pressure of the situation by clinging ever more tightly to their established ways of working. As Peter Senge has noted, our brains tend to ‘downshift’ under pressure and we revert to our most habitual modes of behaviour. Evidence of this can be found in the tendency of some NHS providers, when faced with many competing demands, to adopt a highly bureaucratised form of management that leads to defensive and reactive behaviour and superficial displays of compliance rather than genuine efforts at improvement. Others, meanwhile, are so focused on the task of securing their immediate survival and on short-term business priorities that they do not have the headspace to think about the long-term gains that can come from working collaboratively. Quite simply, they are too busy firefighting the latest crisis to worry about anything else.

In saying this, there is room for some optimism. If you look at the factors that David Gleicher and others have suggested are necessary in order to deliver meaningful change – dissatisfaction with how things are now, a vision of what is possible, an appreciation of how change is to be implemented, and the capacity for change – there are grounds to think that we are close to tipping point on many of them.

With health and social care budgets severely stretched in every UK nation, the financial logic for tackling expensive and resource-intensive bottlenecks in the flow of patients, service users, information and equipment across the system is hard to resist. The moral and emotional case – exemplified by the human costs of delayed hospital discharge of frail, older people – is equally powerful. Moreover, there are enough inspiring examples of effective cross-organisational working – some of which are highlighted in Sections 3 to 5 – to show that real change is achievable even in the most pressured of times.

The renewed interest at national level in prevention and public health, described in England in the Forward View as being in need of ‘a radical upgrade’, is also helping to create the conditions in which local health and social care system leaders are ready to work together to improve flow – or, better still, ensure that people do not need to flow into the system at all. One indication of this is the emerging interest among public service leaders, particularly in Scotland,, in the concept of ‘failure demand’, or ‘demand caused by failure to do something or do something right for the customer’. By focusing on avoiding failure demand, a requirement is placed on health and social care leaders to work alongside their peers across the whole of the public sector, including, but not limited to, housing, education and employment.

There is also a better understanding of the capabilities and methods that can help to deliver whole system change. Senge, for instance, takes heart from the ‘extraordinary expansion in the tools to support system leaders’ to ‘see the larger system’, ‘foster reflection’ and ‘co-create the future’. He argues that the strategic use of these tools ‘at the right time, with the right spirit of openness’ can help to address ‘previously intractable situations’ and inspire confidence that change is possible. What is not in evidence, as yet, is a critical mass of people across the health and social care landscape with the capabilities to use these tools effectively.

This report aims to help local health and social care economy leaders as they begin to think about how to build the necessary capabilities to improve flow on a system-wide level. Section 1.3 describes the core elements of an archetypal local health and social care system, to which this report speaks.

Enabling change across an entire health and social care system is not easy. Even tasks that would appear to be fairly straightforward, such as defining what the system is, can be challenging. If you were to ask a dozen health and social care professionals to define their local system, you would likely receive a dozen different answers, even from people who worked in the same department. Ultimately, it will depend on what each person sees as being the core purpose of the system: those who see the avoidance of failure demand, for example, as being its key organising principle may define the system in broader terms than their peers focused on the operational realities of meeting the needs of the patients and service users in front of them. When change is being planned and delivered, it is important to surface such views early on to avoid potential misunderstandings and conflict at a later stage. Moreover, a shared definition of what is in and out of scope is an essential first step in understanding a system and identifying the weaknesses and constraints within it.

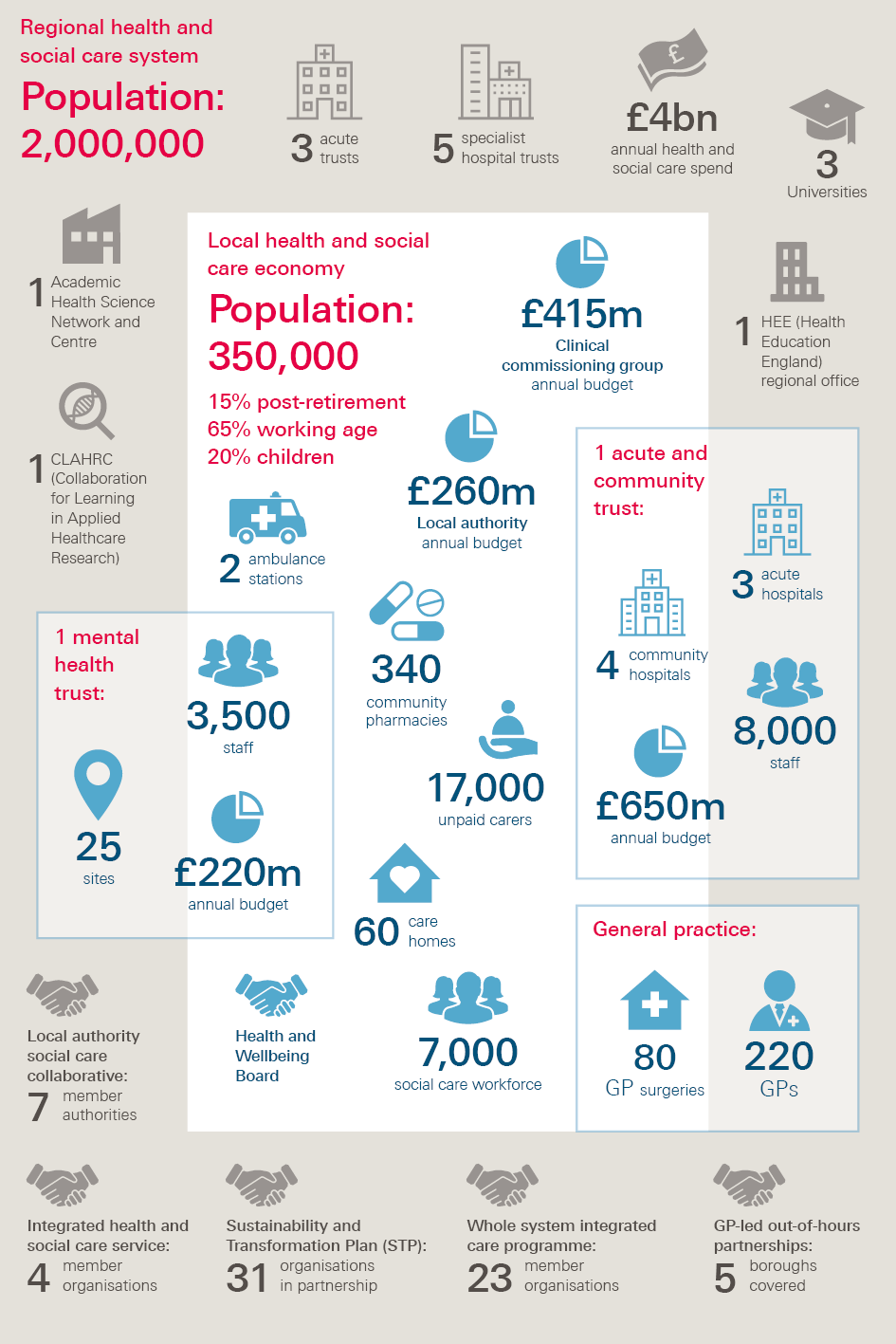

While each set of local leaders will define their systems according to their local context and priorities for action, it is useful to have an archetype in mind when describing, as this report seeks to do, the capabilities and resources needed to improve flow on a whole system basis. Our archetypal system, illustrated in Figure 1, is focused on the organisations that will be involved once a need for care has been identified. This care system sits within a wider system that influences the health and wellbeing of the public. The relationship between these two distinct but interlocking systems is crucial. From a health and social care provider perspective, a close and transparent relationship between them and other partners with a wellbeing focus – which provides scope for joint working, information sharing and peer challenge – will help to ensure that any care system redesign activity is consistent with the needs of the wider population. It may be, after all, that resources allocated towards optimising primary and acute care journeys could have a bigger impact if they were used to address an underlying cause of ill health in the area.

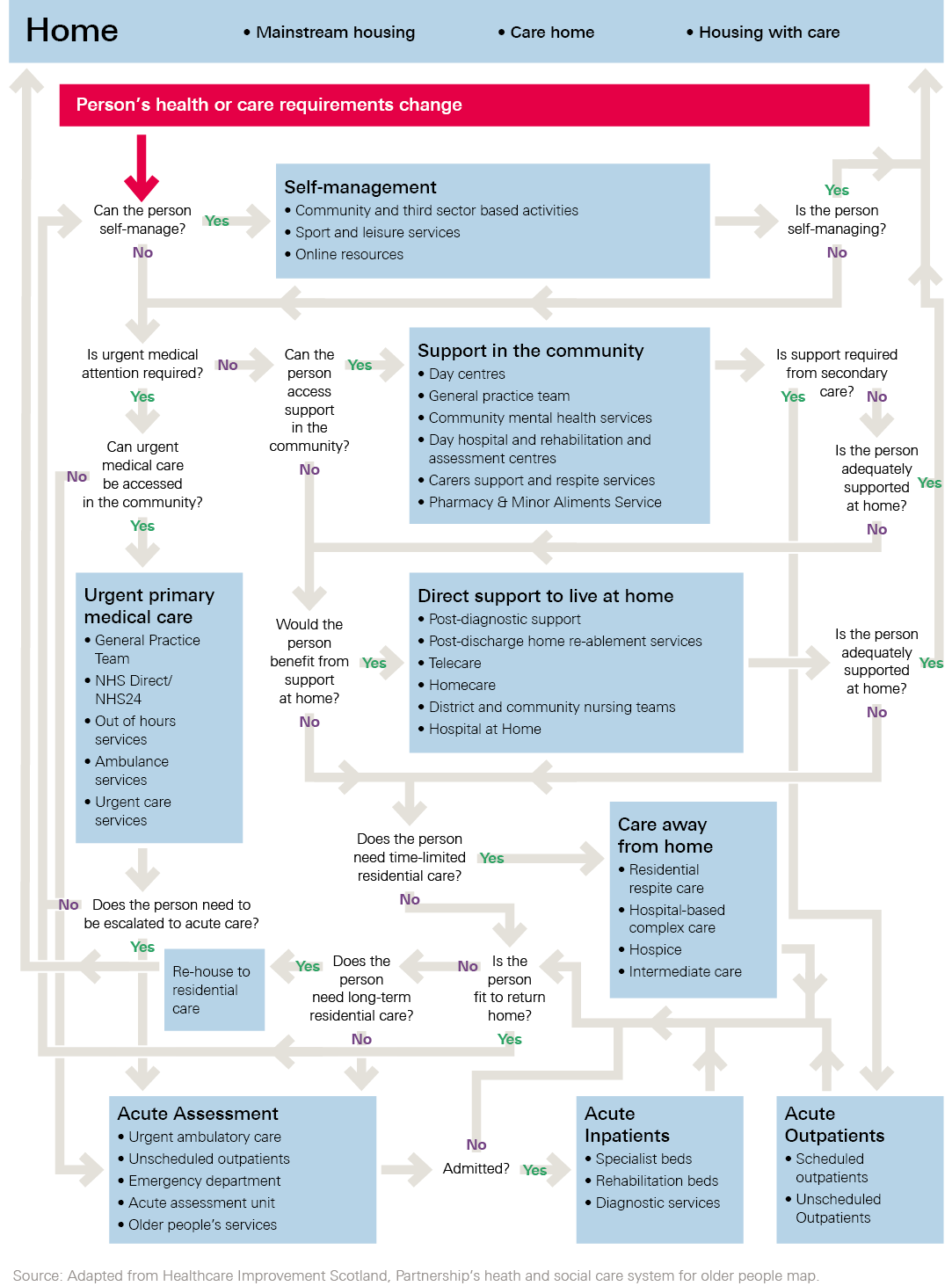

Figure 1 is based on a typical system in England and is designed to illustrate the possible extent of a system-wide approach to improving flow, in terms of the number of organisations, professionals, patients and service users involved. Figure 2 illustrates an example of the care journeys that run through a local health and social care economy. It shows the many teams potentially involved.

Figure 1: Anyborough, England – a local health and social care economy

Figure 2: Anyborough local health and social care economy care journeys

It can be difficult, even for experienced system leaders, to navigate the landscape illustrated in the Figure 1. While this makes flow improvement hard, methods for understanding and improving flow (see Box 1 and Section 3.2) can help to make sense of the landscape. AQuA’s work with organisations in the north west of England has led it to conclude that a focus on patient flow can be an effective way of helping people see and understand the complexity of the system in which they are working. Flow improvement methods provide a means of fostering greater collaboration within and between organisations and designing care models that will better meet the needs of the local population.

The benefit of examining the system through a care journey lens, as shown in Figure 2, is that it allows system leaders to see how services are connected and where constraints may exist. It also allows them to start to consider what activities might be amenable to flow improvement approaches and what resources and capabilities they will require. It may be that approaches which have been primarily used to improve flow in acute contexts may need to be adapted, or may not be applicable at all, to the type of challenges faced by organisations focused on prevention and continuing care.

Identifying flow within the system

The concept of flow is closely associated with the approach to quality and productivity improvement known as ‘lean’ or the Toyota Production System. In their definitive book on the subject, Lean thinking, James Womack and Daniel Jones use health care as a prime example of the lack of flow in a system.

‘What happens when you go to your doctor? Usually you make an appointment some days ahead, then arrive at the appointed time and sit in a waiting room. When the doctor sees you, usually behind schedule, she or he makes a judgement about what your problem is likely to be. You are then routed to the appropriate specialist, quite possibly on another day, certainly after sitting in another waiting room. Your specialist will need to order tests… requiring another wait and then another visit to review the results… If you are unlucky and require hospital treatment, you enter a whole new world of disconnected processes and waiting.’

Lean practitioners argue that the absence of flow arises out of the ‘batching’ of patients, service users and routine tasks, so that they are seen or completed at the same time by members of staff. For patients and service users, this can be incredibly frustrating, as it means that they often have to wait in a queue until the next stage in the process is ready to begin. It is also an enormous source of potential error, duplication and waste.

As well as looking at the flow of patients and service users through a set of care processes, it is important to look at the flow of the information, resources and staff that need to come together to enable effective care of these individuals. In acute settings, the flow of staff to the patient can be critical, for example, having an early senior clinical decision maker available on arrival in an emergency department. Effective flow of information across a system also matters: for example, if all professionals treating a particular patient had access to a shared care record it would significantly reduce waste and delays.

An effective flow of resources is also essential so that a lack of finance in one part of the system – for example, in social care or domiciliary services – does not mean that patients and service users experience a delay in discharge and an unnecessary stay in hospital because there is nowhere for them to go. These different types of flow need to be made visible and purposefully designed and managed to ensure they are mutually supportive.

Understanding flow across the whole system

Once the different flows have been identified, further work is needed to understand variations in demand and capacity within the system and the root causes of them. While there are examples of analysing the flow of patients, service users, data and resources within specific services or organisations, rarely has this been done across a whole system.

Analysing flow across a whole system is a major undertaking. This is especially so given the lack of easily accessible cross-organisational data, and the shortage of analytical capability. Yet, as discussed in Key area 3, such analysis is critical.

While it is important to be pragmatic about the time and resource available for analysing the system, experience from other sectors underscores the importance of doing so. Analysis is especially important when the systems are too big and complex for people to easily see through their direct experience, or to be able to predict how they will respond to change. Consequently, there is a strong case for investing substantially in system analysis before making changes to care processes and services, especially given the potential cost and quality implications of any changes.

Some common approaches that have been used in the UK and other countries to understand flows across complex organisations or care journeys with many variables and interrelationships are described in Box 1.

Box 1: Methods for understanding system flow

SIMULATION AND MODELLING

Simulation and modelling of patient or service user flow can provide insight into where bottlenecks occur in a health care system. They allow service planners to evaluate the benefits and pitfalls of potential improvements before enacting them.

Simulation has been widely used in manufacturing and in the logistics sector with the aim of optimising throughput and profitability. Gatwick Airport, for example, has used simulation of passenger flow through the check-in process to increase understanding of variation and where bottlenecks were occurring. Gatwick was able to make changes to the process as a result and has seen an improved check-in process with reduced queue times and improved airline efficiency.

In health care, simulation and modelling approaches have been used to manage bed capacity, schedule staff, manage admission and scheduling procedures, and to test the value or functionality of new initiatives and services before they are implemented.

The effectiveness of these approaches is often contingent on the quality of the process mapping used to inform them, as well as the robustness of the data used to populate them. Finding sufficient funding and staff with the right skills to build and run simulations is a further challenge.

Resources

- SAASoft has developed a whole system dynamics simulation for education purposes, with five interdependent components: home, hospital, intermediate care, care home and cemetery.

- The Basic Building Blocks methodology published by the Scottish government offers a systematic approach to the demand and capacity analysis of existing care journeys. Its tools can be used for simulation modelling.

Examples from the peer reviewed literature

- In England, researchers used simulation to create a ‘perfect world model’ for accident and emergency (A&E) care – not as it is, but as it could be. Importantly, the ‘efficiency gap’ between the ‘perfect world’ and the ‘real world’ was used to identify the location of bottlenecks in the current ‘whole hospital’ care journey and brainstorm ideas for improvement.

- An English primary care commissioning organisation focused on improving the use of unscheduled care and support efficiency gains in the local hospital. A model of the system was developed to help set usage targets at the micro-level of the hospital. The model drew on a small number of readily available key data items. The model emphasised that primary care had an important role in changing the culture, communication and care provided within A&E and other unscheduled services.

- A Swedish hospital has used a simulation model to support discussions about the resources, capacity and work methods that would be required on a maternity ward that was shortly to be built.

- In Canada, a simplified, low-cost simulation platform, developed using spreadsheets, was found to be as effective in predicting patient flow patterns as more expensive commercial software packages.

VALUE STREAM MAPPING

Value stream mapping (VSM) is an approach that produces a visual map of a system or process.

It is often used by multidisciplinary teams to improve processes as part of lean/continuous improvement projects.

Using VSM, a team can produce a visual map of the ‘current state’, identifying all the steps in a patient or service user’s care journey.

The team then focuses on the ‘future state’, which often represents a significant change in the way the system currently operates. This means that the team needs to develop an implementation strategy to make the future state a reality.

Using VSM can result in streamlined work processes, reduced costs and increased quality.

Resources

- The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement produced a guide to using VSM.

- Another useful guide to VSM can be found on NHS Scotland’s Quality Improvement Hub.

Examples from the peer reviewed literature

- In Ireland, researchers used lean principles and the theory of constraints to identify bottlenecks in patient journeys through A&E. For each stage of the patient journey, average times were compared and disproportionate delays were identified using a significance test.

- A value stream map and the five focusing steps of the theory of constraints were used to analyse these bottlenecks.

- A US multidisciplinary team analysed the steps required to treat patients with acute ischemic stroke and developed a streamlined treatment protocol.

QUEUEING THEORY

Queuing theory, or the study of waiting lines, or queues, can help to understand and address mismatches between service demand and capacity. Usually a mathematical model is constructed to help predict queue lengths and waiting times. Historical data are analysed to explore how to provide optimal service while minimising waiting, thus providing an objective method of determining staffing needs during a specific time period. Popular in other industries, queuing theory has also been used in health care, particularly by hospitals wanting to understand waiting times for unscheduled care or the time spent waiting for specific equipment, surgery or laboratory results. It is also applicable to wider systems of care or transitions.

Examples from the peer reviewed literature

- A hospital in England used queuing theory to analyse one year’s worth of data to help understand the practical challenges associated with variation in patient demand for services and length of stay. The analysis found that daily bed shortages are mostly influenced by the timing of arrival and discharge of patients with a short length of stay, and that bed shortages around holiday periods are not due solely to increased demand, but also a reduction in staff and service capacity in and out of hospital around these times.

- In Canada, researchers used queuing theory at an organisational level to analyse the relationship between patient flow to A&E and patient flow to the inpatient unit. They then used the model to estimate the average waiting time for patients and the resources needed in unscheduled and inpatient care. The model was used to analyse the potential impacts on waiting time and resources of an alternative way of accessing unscheduled care and this helped managers plan the resources needed to enhance patient flow.

- The Scottish Whole System Patient Flow programme has also been informed by queuing theory (see Box 5).

Experience of improving flow at a system level

In recent years, there has been a significant growth in thinking about how to improve flow within health care processes and systems. One of the leading experts in the field, Eugene Litvak suggests that to improve flow in a health care setting it is necessary to:

- understand variation in the performance of a process over time and its sources

- separate patient flows into appropriate streams

- redesign work processes for those streams to smooth out the flow

- match capacity with estimated demand.

Around the world, a number of hospitals have worked to redesign care journeys in order to improve flow using these principles (see Box 2).

Within the UK, the Royal Bolton Hospital took a similar approach between 2004 and 2010. This led to improvements in quality and productivity. For example, a redesign of the process for patients with fractured hips reduced length of stay by 33% and reduced standardised mortality by 50%. An audit concluded that there had also been a 42% reduction in paperwork for the staff involved.

More recently, flow improvement programmes have been implemented across Wales and Scotland (see Box 3).

The Welsh Patient Flow programme, which involved all health boards with general hospitals that admit emergency patients and the Welsh Ambulance Service, has succeeded in delivering some improvements in flow in local pathways. It has also generated some valuable learning about the challenges involved in using a national breakthrough collaborative model to improve flow across multiple sites at the same time.

However, while primary, community and social care services have been involved in the Welsh programme, much of the improvement activity has focused on the acute sector. The same is true of the Scottish Whole System Patient Flow programme, which got underway in 2013, a few months after the Welsh programme.

The challenge now is to build on this work to improve flow within hospitals, and develop approaches which look at flow across the whole of the health and social care system. This would involve the smoothing of demand upstream – in particular in general practice – and the development of community resources downstream to allow a smooth and safe flow of patients out of hospital once they are fit for discharge.

Box 2: International examples of flow improvement programmes

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital implemented a series of measures to match capacity with demand and improve quality. It reported a cost avoidance of $100m in capital costs and an increase in its margin of more than $100m annually.

‘Esther’ in Jönköping in Sweden was led by a team of physicians, nurses and other providers who joined together to improve patient flow and coordination of care for older patients within a six-municipality region. It reported significant reductions in hospital admissions, days spent in hospital by heart failure patients, and waiting times for referral appointments with a range of specialists.

Intermountain Healthcare is an integrated system in Utah and Idaho in the US that consists of 23 hospitals and 160 clinics and has a workforce of 32,000. Its improvement journey, which began in the late 1980s, has been influenced by Deming’s insight that the best way to reduce costs is to improve quality. Intermountain has driven improvement by focusing on measuring, understanding and managing variation among clinicians delivering care. In the past 20 years it has delivered more than 100 clinical improvement initiatives that it reports have improved outcomes and reduced costs. The introduction of an elective labour induction protocol, for example, has helped to reduce the rate of caesarean sections and saved around $50m each year in Utah.

Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Florida, reported savings of $5.3m by adopting lean principles across the organisation. It also recorded improvements in unscheduled admission rates and overall patient flow.

The Mayo Clinic in the US used variability methodology to analyse surgeries over a three-month period and construct models of the resources used for scheduled and unscheduled cases. Guidelines were implemented to smooth the daily schedule and minimise variation. It reported a range of improvements in its productivity and resource use. Overtime staffing decreased by 27%, the number of elective scheduled same-day changes decreased by 70% and net operating income improved by 38%.

Seattle Children’s Hospital used Integrated Facility Design, an adaptation of the Toyota 3P process, to design a surgery centre with reduced variation and improved cost-effectiveness. Using this approach resulted in completion 3.5 months ahead of schedule, with estimated savings of $30m in project costs and improved patient throughput.

Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle is a leading example of the application of the Toyota Production System principles, or ‘lean’, to improve flow. After adopting lean as its management system in 2002, the center has reported appreciable and sustained improvements in clinical outcomes, safety, patient satisfaction, process indicators, staff engagement and costs. The prevalence of hospital acquired pressure ulcers, for example, fell from 5% to 1.7% between 2007 and 2012. Liability claims also dropped by over half and the centre achieved positive financial margins each year through efficiency savings, after previously losing money in consecutive years. It has also been named as ‘top hospital of the decade’ by Leapfrog and has been ranked in the top 1% of US hospitals for quality and efficiency.

Its success has been underpinned by an improvement approach – the Virginia Mason Production System – which seeks to standardise processes where possible, streamlining repetitive aspects of care to reduce waste and free up staff time with patients. All 5,500 staff at the centre are trained in the approach. The emphasis is on creating a culture of learning throughout the organisation, which can be applied successfully to drive continuous improvement.,,,

Box 3: UK examples of national flow improvement programmes

The Scottish government has developed two programmes that focus on flow, primarily within acute systems:

- Launched in 2013, the Whole System Patient Flow programme, which has been delivered in collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Optimization (IHO), contains a number of acute-focused workstreams. The programme draws upon IHO Variability Methodology® and ‘classic queuing theory’ to describe and achieve ‘optimal flow’. Four territorial health boards have well-established projects; a further six (of a total of 14) have completed a Scottish Patient Flow Assessment and are starting their own pilot projects.

- The Unscheduled Care programme, launched in May 2015, is focused on achieving the four-hour emergency Access Standard across Scotland through six essential actions. The programme has adopted a collaborative approach underpinned by measurement for improvement and other quality improvement approaches. The building blocks of the programme involve six high-level themes, which are managed both individually and collectively. NHS Scotland has reported that this whole system approach has helped to improve flow for over 40,000 people in the last year: long waits of 8 hours and 12 hours have improved by 92% and 100% respectively.

The Welsh 1000 Lives Patient Flow programme was launched in June 2013 and ran until August 2015. It aimed to develop organisational capability and improve the effectiveness, efficacy and efficiency of the system for managing the care and flow of patients from the point of unscheduled entry, through diagnosis and treatment to discharge. Participants in the national roll-out of the programme included the Welsh Ambulance Services Trust (WAST) and the six Local Welsh Health Boards (LHBs) with general hospitals that admit emergency patients.

The programme was publicised as a ‘Breakthrough Collaborative’, modelled on the work of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and its conceptualisation and design was informed by the Health Foundation’s Flow Cost Quality programme. It had three main components: national learning events, a computer-based training course, and local workshops at each of the participating sites. The programme has achieved some improvements to patient flow within certain pathways and has led to the sustained use by some LHBs of the Big Room process and the A3 structured problem-solving process (see Case study 1 for details of these processes). However, it has proven more difficult – certainly within the relatively limited time and resources allocated to the programme – to deliver wide-scale improvements across participating sites.

Summary

This section has highlighted the importance of improving flow across whole health and social care systems. It has summarised what is known about how to develop a deeper understanding of flows and offered international and UK-based examples of what can be achieved through the application of flow improvement methods. While these methods have significant potential to help address the challenges faced by the system, realising this will require long-term commitment and investment.

Section 2 proposes an organising framework to guide such efforts. It identifies four levels of action that need to be woven into a coherent strategy to realise the potential of flow improvement.

‡ See glossary for definition of these terms, as well as others used in this report.

§ Eugene Litvak is at the Institute for Healthcare Optimization, which is supporting the Scottish Whole System Patient Flow programme.

¶ ‘upstream’ refers to services encountered early in a care journey (eg primary care), while downstream refers to those encountered at a later stage (eg secondary or tertiary care). See glossary for more details.

An organising framework for improving whole system flow

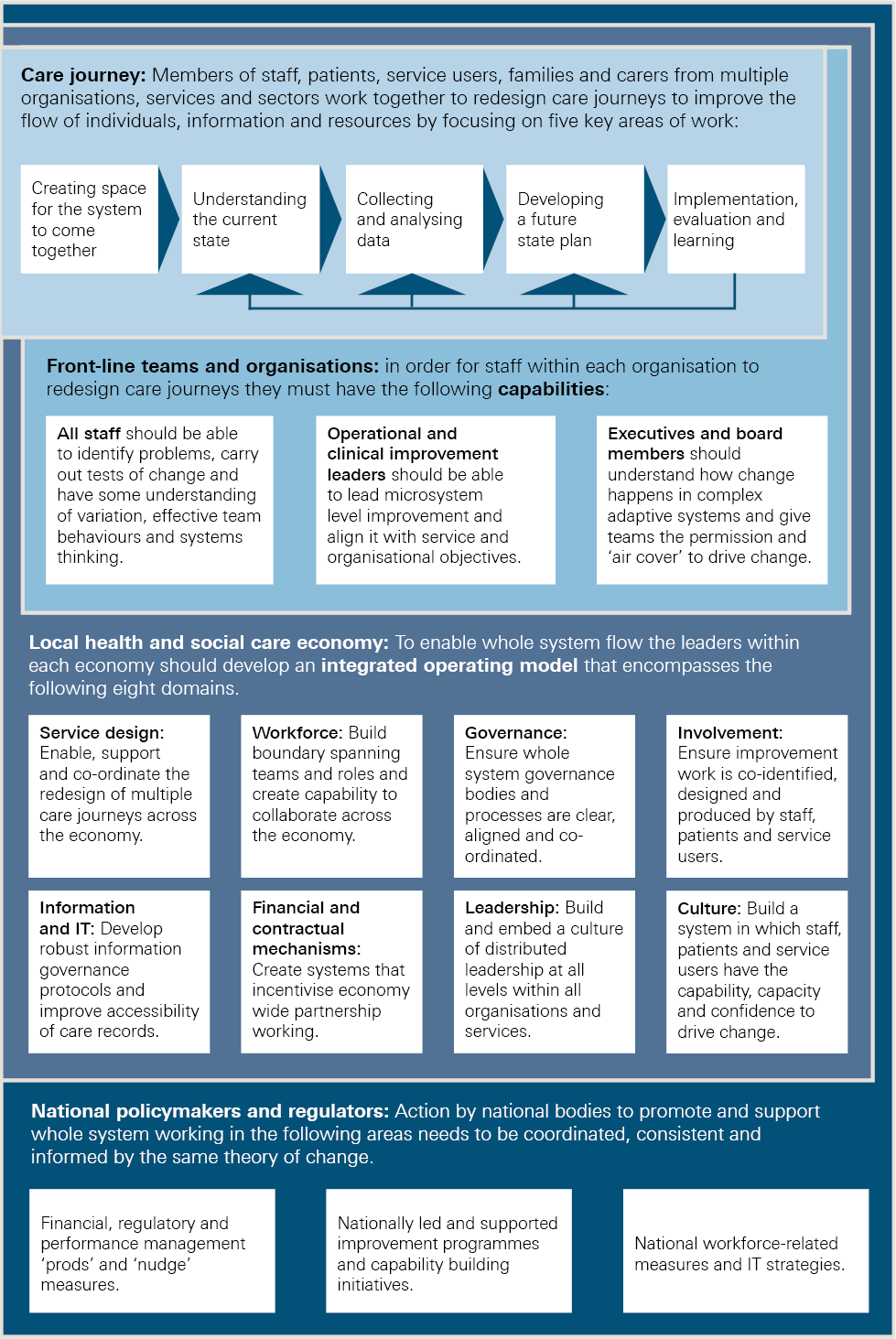

The need for a multi-level approach

Significantly reducing waste and waiting from local health and social care systems will require a joined-up development strategy operating at multiple levels (see Figure 3). At the care journey level, the tools and techniques of lean provide helpful insights into how to tackle bottlenecks and remove waste, delays and duplication. For this work to be successful, however, communities also need to invest in the improvement skills and capacity of front-line teams and organisations so that they are capable of continually improving the quality of the work they do. Senior system leaders within each local health and social care economy also need to identify and address the local issues that may impact effective whole system flow. Finally, national policymakers and regulators have a role to play in creating an environment that is conducive to improving whole system flow.

In developing and implementing a strategy across these levels, it is important to recognise that improving flow is much more than just a technical challenge. Behaviours and relationships matter as much, if not more. The ability of local health and social care economies to foster a culture of learning behaviour is critical. This culture is one where members of staff at all levels are in the habit of ‘repeatedly accumulating insights, improvements and innovations, and putting them to good use’, as Steven Spear put it. Equally valuable is the capacity to work collaboratively with people with different professional values and ways of working. In many cases, the success of large-scale change rests on the quality of these relationships.

Resilience is also crucial. On the shifting sands of the health and social care landscape – where new performance challenges are always emerging, strategic priorities and leaders come and go, and partnership arrangements are in a state of constant flux – it can be difficult to maintain enthusiasm and the momentum for change. Every change journey is pitted with obstacles and has points when things appear to be going backwards rather than forwards, putting hard-won gains in jeopardy. An ability to pick up the pieces after such setbacks and begin again is one of the most essential improvement skills, yet is rarely mentioned or appreciated.

The rest of this section provides an overview of what is needed, at each level, to improve whole system flow. Sections 3 to 6 discuss what is possible at each of the four levels in more detail.

Figure 3: An organising framework for improving flow across multiple levels

Care journeys

In looking to improve whole system flow, it is important for the work to be underpinned by a sound understanding of what it is like for patients and service users as they flow from one service to another. Anyone who requires care for acute or chronic conditions is likely to have a care journey that crosses multiple professional and sectoral boundaries in both community and institutional settings.

Focusing on the experiences of patients and service users will not only help to reveal examples of waste, delay and duplication within care processes, it will also ensure that priority is given to the aspects of care that matter most to those receiving it. After all, the overriding purpose of any effort to improve whole system flow should always be to provide an improved experience and better outcomes for patients and service users.

Getting care journeys to flow more smoothly at every point, so that patients and service users have a good experience, regardless of which team or service is providing their care, is a considerable challenge. As has already been noted, most efforts to improve flow have not attempted to tackle whole care journeys, but have concentrated on the in-hospital element. There is a pressing need to broaden the focus of attention to cover every team, service, profession and organisation that has a role to play in the care journeys of patients and service users.

Front-line team and organisational capabilities

The care journey level is the primary focus when thinking about improving flow, but it is also important to think about the contribution of each front-line team along that journey. Womack and Jones argue that for systems to operate effectively, each step in the process must be ‘capable’, so that it produces a good result every time.

If parts of the system are under-resourced or poorly designed, then well-meaning efforts to create flow may only lead to a slightly more joined-up collection of dysfunctional processes. For example, a hospital’s emergency department and wards may be operating effectively, but if social work support or community nursing teams are under-resourced or ineffective then waste and delays are inevitable. Similarly, efforts to strengthen out-of-hospital care might founder unless hospital pathways have been redesigned to prevent avoidable admissions, minimise length of stay and promote recovery. As the theory of constraints suggests, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link: movement along a process, or chain of tasks, will only flow at the rate of the task that has the least capacity.

This means that investment in continuous quality improvement at the team or unit level is vital. As well as having the right skills and resources, teams need to be able to work effectively alongside each other. For this to happen, teams at each part of the care journey ideally need to understand the same improvement language, and have experience of using similar improvement methods and tools. A shared understanding of what the system is and what the teams are collectively trying to achieve is also key. Experience among those that have developed successful approaches to integrating care shows that the co-location of staff from different disciplines and agencies can be helpful in breaking down cultural barriers.

It is also important to recognise that an understanding of improvement methods and tools at team level is not enough in itself to secure meaningful change., It has to be accompanied by willingness and capacity to spend time studying the system and identifying the constraints preventing effective flow. Understanding what matters to patients and service users, and focusing on how to improve their experiences, is also critical. Change programmes that focus largely on the spread and uptake of tools and techniques will often only achieve minor process improvements that are hard to sustain. The improvement journey of Winona Health in the US, which is explored in Case study 4, illustrates this point well. Winona’s information approach has shifted from one that was largely focused on tools and projects in its early years, to one that now focuses on ‘deep cultural change’ across the organisation and understanding what matters most to patients and the wider community.

Any attempt to improve whole system flow across an entire local health and social care economy needs to be underpinned by an effective infrastructure for collaboration. Financial incentives and contracting arrangements, information governance, service models and workforce challenges all need to be tackled. These issues cannot be addressed successfully by local system leaders without attention being paid to leadership, culture and the effective engagement of staff, patients, service users and communities. Failure to tackle them will inevitably frustrate efforts to improve the flow of patients, service users, staff, information and resources across organisational and sectoral boundaries.

As things stand now, the barriers to effective collaboration across organisational boundaries probably outweigh the enablers. At a time of severe financial pressures and mounting demand, many organisations and services are, perhaps understandably, more focused on dealing with their own immediate crises rather than the needs of the entire local health and social care economy. When opportunities for collaborative working among system leaders do emerge, it is not uncommon for the conversation to be dominated by structural and governance issues, rather than the deeper question of how to improve the relationship between the processes and teams within the economy.

Part of the problem is that emerging partnerships are often unable to dedicate sufficient time and resources to make the most of their collaboration. Participants hardly ever get the chance to get to know each other before embarking on a series of formal meetings and negotiations. Yet informal conversations are often crucial in building strong, trusting relationships and in surfacing concerns and potential obstacles at an early stage. Having the right skills to collaborate with others or to facilitate collaboration is essential: good intentions alone are not enough.

To achieve genuine whole system flow, local health and social care economy leaders need the capability and capacity to collaborate effectively and focus on the key issues this report has already described.

National system change levers

In what is still a highly centralised health and social care landscape, national bodies across the UK have a pivotal role to play in creating the right conditions for local change and helping to maintain its momentum over time. The activities they undertake tend to fall into three categories:

- First, national bodies have the ability to ‘direct, prod, or nudge’ local organisations into change through the financial, regulatory or performance management levers at their disposal.

- Second, they can support change through nationally led programmes or by investing in local improvement and leadership capability. However, to date, rather more attention and resources have been expended, in England at least, on ‘exerting regulatory control than on supporting improvement’.

- The third way in which national bodies can influence change is through the national mechanisms governing the training, recruitment, employment and regulation of people who work in the health and social care system.

A key challenge for national bodies is to ensure that the levers they deploy are aligned. In England, for example, measures to promote whole system working through Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) and new models of care have to be backed up with regulatory and performance nudges that are informed by a shared understanding of how to achieve change. Ideally, they should also be designed, planned and introduced in a joined up way. Action by national commissioners and support and oversight bodies (eg NHS England and NHS Improvement) needs to be in sync with the action taken by regulatory bodies (eg the Care Quality Commission) to monitor, regulate and inspect services. In some cases, national programmes are up and running before regulators have been able to develop a strategic response and turn it into a comprehensive and integrated set of activities. Meanwhile, measures that were developed for a different purpose and are now outdated – for example, the Payment by Results tariff system – need to be reviewed, as they could undermine the drive towards integrated working. Equally, action is required at national level to help address regional and sector-related staff shortages, as well as the high levels of staff turnover and reliance on temporary or agency staff, which could seriously impede local change strategies.

Crucially, national bodies across the UK have a responsibility to provide local system leaders with the time and space they need to deliver genuine transformation. At present, there is risk of a disconnect between an understandable focus from regulators on short-term performance and the long-term steps that health and social care economies need to take to deliver sustainable change. This question will be explored in more detail in Section 6.1.

Case study 1: The Flow Cost Quality programme

The Flow Cost Quality programme, which ran from 2010 to 2012, involved two trusts in England: Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust.

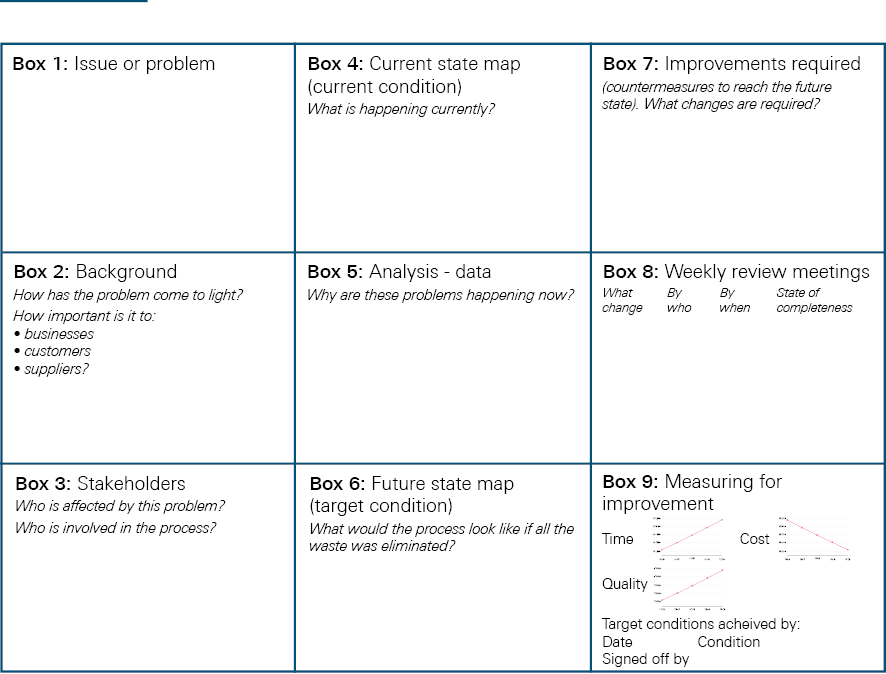

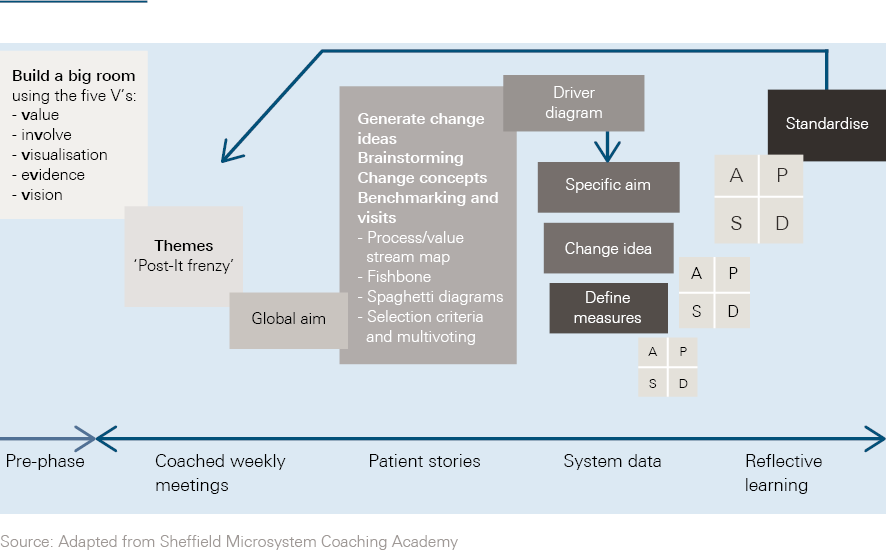

The programme was set up to help the trusts examine their emergency care pathways and to develop ways in which capacity could be better matched to demand, thus preventing waste and poor outcomes for patients. Both trusts were encouraged to use a structured problem-solving methodology – the lean A3 improvement process – which is designed to enable teams to identify, frame and then act on problems and challenges. The process takes its name from the A3-sized problem-solving charts developed by engineers at Toyota. ‘A3 thinking’ has been described as being ‘the key to Toyota’s entire system of developing talent and continually deepening its knowledge and capabilities’. The approach encompasses a set of structured steps to:

- describe the scope of the issue or problem and the measures for improvement

- understand the current state from both the providers’ and customers’ perspectives

- collect and analyse data to better understand the nature of the problem

- develop a ‘future state’ plan with non-value adding activities being eliminated and a smoother flow established

- agree and implement a programme of improvement projects to implement that plan using a rapid cycle of ‘plan, do, study, act’ (PDSA) to test out potential improvements

- continuously monitor progress, evaluate results and feed back learning.

One version of an A3 working document, which is designed to be updated by teams after each iteration, is set out in Figure 4.

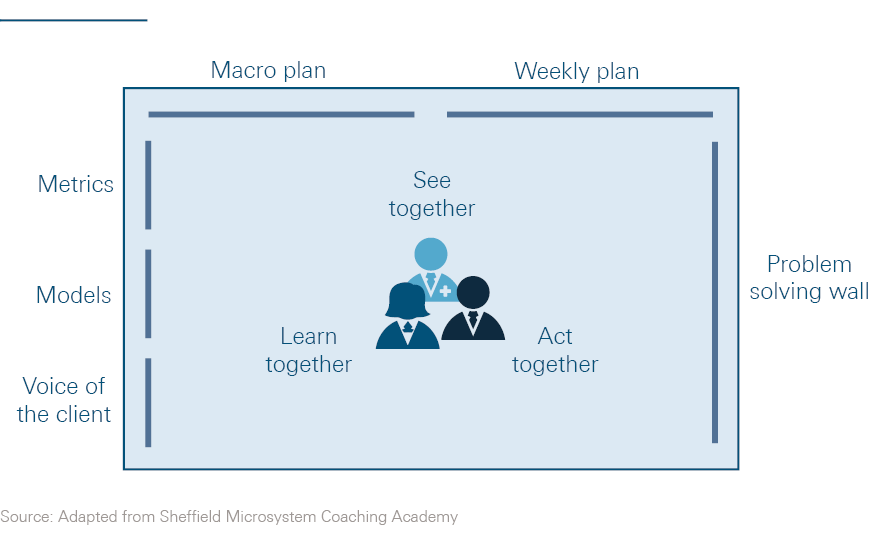

In Sheffield, there was an emphasis on bringing key stakeholders from across the pathway together in the same place to work collectively on identifying and solving problems. This was known as the ‘Big Room’ approach – or by the Japanese term ‘Oobeya’. The participants in each weekly meeting included clerks, secretaries and managers, as well as clinicians and allied health professionals from acute, primary, community and social care settings (see Figure 5).

Attendance was voluntary, and facilitators endeavoured to create an open, honest and collaborative atmosphere in which each individual, regardless of their position in the hierarchy, felt empowered to contribute on an equal footing. Attendees were also encouraged to see the Big Room as part of a process of continuous improvement, through which they would discover their way to a solution through small tests of change, rather than a discrete time-limited project geared towards implementing a pre-ordained solution.

The Flow Cost Quality team in Sheffield focused on the care of frail older people. They identified significant delays in patients being referred to hospital as an emergency by GPs and subsequent delays at each stage of the process. As a consequence, two-thirds of frail older patients arrived on the medical assessment unit after 6pm in the evening when there were fewer senior staff available to assess them. Most had to wait until the following morning to receive a review by a senior clinician.

The team implemented a range of changes to reduce batching and delays and to improve the quality of care. These included the introduction of a frailty unit, which brings together in one place all of the specialist medical, nursing and therapist staff who deal with frail older people. The team also developed an innovative model known as ‘discharge to assess’, which allows frail older patients to be discharged home as soon as their acute medical needs have been met. Within a few hours of the patient’s arrival at home, the trust’s community staff assess their continuing care, equipment and ongoing rehabilitation needs.

The team in South Warwickshire, meanwhile, worked on emergency care for all adult patients. As in Sheffield, they began by mapping processes and testing changes using a PDSA approach. Innovations included ways of matching consultant availability to variation in demand, and bringing senior clinical assessment closer to the start of the process. There was a particular focus on ensuring that support processes were capable and aligned in order to facilitate flow. For example, the number of same-day blood test results available on ward rounds was increased from less than 15% to more than 80%. Because of these up-to-date results, consultants were able to make quicker and safer clinical decisions for patients.

The Flow Cost Quality programme produced encouraging results in both trusts, which have been sustained over time. Moreover, the improvement approach underpinning this success has been spread more widely across the trusts and the local health and social care system.

In Sheffield, the ‘discharge to assess’ model – which began with a small test of change with one patient on one ward – has now been spread throughout the city’s hospital system. More than 10,000 patients have now been transferred out of the hospital into a service called ‘active recovery’, which is a health and social care collaborative aimed at ensuring that their needs are met and addressed in real time. This has resulted in a reduction in the length of time from completion of medical care to home support from 5.5 days to 1.2 days. The Big Room process, meanwhile, is now being used to help improve flow along a series of other care pathways within the city. It has also spread to Wales, where it has proven to be one of the most widespread and valued elements of the Welsh 1000 Lives Patient Flow programme.

South Warwickshire has reported a nine-point fall in mortality rates from 1.11 in 2011/12 to 1.02 in April 2015. Over the same period, the length of acute stay for all patients fell from 7.7 days to 6.2 days, while the reduction for patients aged over 75 was even greater – down by 3.1 from 12.6 days to 9.5 days. Crucially, this reduction in length of stay has not been accompanied by an increase in emergency readmissions. The trust has also managed to cut the proportion of patients who had to make more than three bed moves during their time in hospital from 14% to just 2% between 2011/12 and April 2015. It has also developed its own successful discharge to assess initiative, which is built on effective partnership working with local primary, community and social care providers.

Figure 4: The ‘A3’ chart (not necessarily on A3 paper)

Figure 5: The Sheffield ‘Big Room’

** An effective health and social care system is one in which individuals are able to engage with services at a time and in a place that is appropriate to their needs and wishes. While each journey is different, it is possible to identify some common processes which are amenable to standardisation and can deliver improved flow.

†† The suite of programmes and guides on whole systems working that were developed by the NHS Modernisation Agency and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, highlighted in Section 1.1, are good examples.

‡‡ For example, by 2012, Sheffield had achieved a 37% increase in patients who could be discharged on the day of admission or the following day with no increase in the readmissions rate. The trust also reported a decrease of in-hospital mortality for geriatric medicine of around 15%. Further results can be found on pages 34-39 of Improving patient flow. www.health.org.uk/publication/improving-patient-flow

§§ For a description of how to use the A3 chart, see pages 16-17 in the Health Foundation report, Improving patient flow: how two trusts focused on flow to improve the quality of care and use available capacity effectively. www.health.org.uk/publication/improving-patient-flow

Care journeys

Redesigning care journeys

Anyone who has been a patient or service user, or supported a family member through an episode of illness, will know that we do not have a perfectly designed health and care system. At times it feels like it is for patients, service users and families themselves to ‘join the dots’ and make connections between agencies, rather than being supported to do so by the system. This is a reflection of the fact that the system has typically not been ‘designed’ at all. It has evolved over time in various ways, dependent on local history and circumstance. This also puts considerable stress and burden on members of staff, who need to make sense of ill-defined, fragile and often chaotic systems while managing the workload associated with them.

Ideally, in every care journey there would be a chain of interconnected processes, which have been deliberately designed and managed to meet the needs of patients and service users and to maximise flow and reduce waste, delays and duplication. It should be clear who has responsibility – both for managing the overall process and for the clinical management of each patient or service user. This would help ensure an appropriate and effective flow of information and resources.

In their book Lean solutions, Jones and Womack argue that many of the same disciplines and methods that have yielded improved quality and productivity in manufacturing can also transform the outcomes and experience of consumers in complex service environments such as health care. They set out the following principles of ‘lean consumption’ from the customer’s viewpoint:

- Solve my problem completely.

- Don’t waste my time.

- Provide exactly what I want.

- Deliver value where I want it.

- Supply value when I want it.

- Reduce the number of decisions I must make to solve my problems.

In the health and social care context, we should also add ‘engage me as a full partner in my own care’, with a view to ensuring that efforts to improve the quality of care are co-identified, co-designed and co-produced by those providing and using services.

In recent years, the level of time and resources given to capturing the opinions and experiences of patients and service users about their care has grown appreciably: surveys, online feedback and focus groups are now commonplace in health and social care. The use of patient shadowing techniques and observation of patient and professional engagement is also on the rise. But it is still unusual to find examples of service redesign projects that have been shaped and driven from the start by patients or service users, operating as active and equal participants in the change process., Given that all services, unlike goods, demand some form of interaction between those providing them and those using them, and as such are ‘co-produced’, there is a pressing need to address this deficit.

The Health Foundation’s Flow Cost Quality programme was a concerted attempt in the NHS to address the challenges identified by Jones and Womack. The programme set out to improve patient flow along the urgent and emergency pathway in two NHS foundation trusts in England (see Case study 1). Much of the learning from the programme is highly relevant for communities wishing to tackle the topic of improving flow on a genuinely whole system basis. It demonstrates that a combination of lean approaches, strong system leadership and broad stakeholder engagement can be employed to reshape health and social care services and deliver sustained productivity gains and improved patient outcomes and experiences.

However, there are additional challenges that need to be addressed when attempting large scale change across multiple settings and stakeholders in local health and social care economies. These are discussed in Section 3.2.

Using a structured approach to improve flow

As described in Case study 1, the A3 problem-solving process was one of the key methods used by Sheffield and South Warwickshire to help them analyse their systems and develop tests of change as part of the Flow Cost Quality programme. As well as helping the teams to understand the root cause of problems and test solutions, it proved to be a powerful method for changing the beliefs and behaviours of those involved. It can be adapted for use on a whole system basis by addressing five key areas of work:

- Creating space for the system to come together

- Understanding the ‘current state’

- Collecting and analysing data

- Developing a ‘future state’ plan

- Implementation, evaluation and learning.

Key area 1: Creating space for the system to come together

The system described in Figure 1 gives an example of the various stakeholders in England that could be involved in providing diagnosis, treatment, care and ongoing support. A wide range of professionals employed by a multitude of agencies need to work together effectively in patients and service users’ own homes, in other community settings, and in a range of institutions including care homes, hospitals and inpatient mental health units. Some service providers will have daily contact with a few other agencies, but none are likely to see the totality of the system and how its different elements interconnect.

Making the system visible to itself is no easy task. Box 1 explores some of the methods that have been used to understand flows across organisations. Box 4 overleaf describes the process that has been set up in Wigan with a view, among other things, to giving system leaders the time and space to focus on care integration.

Box 4: Wigan Integrated Care Partnership Board

Wigan Borough established an Integrated Care Partnership (ICP) Board in 2016. This draws together key statutory partners including Wigan Council, Bridgewater Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (the community services provider), 5 Boroughs Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (the mental health provider), Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust (the local acute hospital), Wigan Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and GP representatives from five geographically based primary care clusters that cover the whole community. These partners are committed to working together to provide more joined-up services for the local population.

There has been early recognition by the ICP Board that they need to engage with a much wider range of partners. Consequently, a stakeholder forum is being established to encompass education, housing, the criminal justice system, the ambulance service, and voluntary and community organisations, as well as other primary care providers such as dentists, pharmacists and opticians. The council already has a number of well-developed mechanisms for engaging citizens in its work, both individually and collectively, and these are to be used as the partnership seeks a new deal with local people, through which the council, businesses and residents work together to improve the borough. A key element of this work is an increased focus on wellness and prevention, as described in Case study 3.

Many communities have similar arrangements to Wigan for drawing together partner organisations. However, there is a risk that they fail to reconcile the competing perspectives, values and assumptions of the partners, and are unable to develop a shared view of the problem to be addressed. The use of a structured method such as the A3 can help guard against this by creating a common vision, goals and approach to improvement. In this way the system not only becomes ‘visible to itself’ but is aligned towards a shared purpose.

The value of these methods hinges, as we have stated, on the time, resource and commitment that participating members are prepared to invest in them. Building trust between people working in different organisations and professions takes considerable time and effort. Each participant needs to approach the exercise with a degree of humility – they must recognise that no single organisation has the capacity, insight or authority to solve a system-wide challenge on its own. This is particularly important in the health and social care world, where historic resource, power and prestige imbalances between organisations and professions can make it difficult to ensure that each participant enters the collaborative process on an equal footing. Highlighting the unique expertise and knowledge that each participant brings to the process, and the particular challenges they face in their part of the system, can help in this respect. It gives each organisation the opportunity to demonstrate that many of the challenges they face are more entrenched and multi-faceted than their partners may have realised, and that they cannot be solved simply with more resources or by a technical fix.