Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues who have informed and supported this work. We are grateful to our external reviewers Theresa Marteau, Steven Cummins, Hazel Cheeseman and Caroline Cerny. We would also like to thank Health Foundation colleagues Hugh Alderwick, Jo Bibby, Katherine Merrifield, Gwen Nightingale, Adam Tinson, Sean Agass and Jennifer Dixon.

Errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors alone.

When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2022-P10.

Key points

- The UK’s health looks increasingly frayed and unequal. Even prior to the pandemic, people were living more years in poor health, gains in life expectancy had stalled, and inequalities were widening. This has a costly impact on individuals, communities, public services, and the economy.

- Smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol use are leading risk factors driving the UK’s high burden of preventable ill health and premature mortality. All are socioeconomically patterned and contribute significantly to widening health inequalities.

- This report summarises recent trends for each of these risk factors and reviews national-level policies introduced or proposed by government in England between 2016 and 2021 to address them. Based on our review, we assess the government’s recent policy position and point towards policy priorities for the future.

- There are stark warning signs that government needs to shift its approach to improve health. Rates of childhood obesity have risen sharply in recent years and inequalities have widened. Smoking remains stubbornly high among those living in more deprived areas. Alcohol-related hospital admissions and deaths have increased and rates of harmful drinking have gone up. Physical activity levels also remain low and appear to have declined during the pandemic.

- Population-level interventions that impact everyone and rely on non-conscious processes are most likely to be both effective and equitable in tackling major risk factors for ill health. Yet recent government policies implemented in England have largely focused on providing information and services designed to change individual behaviour.

- As well as relying heavily on policies that promote individual behaviour change, our review shows that the strength of the government’s approach has been uneven for the leading risk factors, and decision making across departments has been disjointed. Action to tackle harmful alcohol use in England has been particularly weak.

- To reduce exposure to risk factors and tackle inequalities, government will need to deploy multiple policy approaches that address the complex system of influences shaping people’s behaviour.

- Population-level interventions that are less reliant on individual agency and aim to alter the environments in which people live should form the backbone of strategies to address smoking, alcohol use, poor diet and physical inactivity. These interventions need to be implemented alongside individual-level policies supporting those most in need. The strong role played by corporations in shaping environments and influencing individual behaviour must also be recognised and addressed in a consistent way through government policy.

- Some of the biggest immediate gains could be made by adopting price-based policies, taxes and regulations already proposed in previous government documents. Examples include minimum unit pricing for alcohol (already introduced in Scotland and Wales); a sugar and salt reformulation tax; and raising the age of sale for tobacco from 18 to 21.

- The costs of government inaction on the leading risk factors driving ill health are clear. As the country recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and seeks to build greater resilience against future shocks, now is the time to act.

Introduction

Why government needs to act

A healthy population is an asset for any nation, supporting positive social and economic outcomes for individuals and society.,,, Across a number of measures, however, the UK’s health looks increasingly frayed and unequal., In the decade prior to the pandemic, improvements in life expectancy were lower than in most European and other high-income countries. People are living more years in poor health and inequalities in how long those in the most and least deprived parts of the country can expect to remain in good health are widening., Those living in the north of England, Scotland, and the South Wales Valleys have particularly low average healthy life expectancy compared to other parts of the country, with a gap of almost 20 years between women living in the richest and poorest areas.

International data show that relative to comparable European countries, the UK also has a higher prevalence of largely preventable, non-communicable conditions including some types of cancer, diabetes, COPD, asthma and obesity.,, This is costly for individuals and the economy. More than a third of those aged 25–64 in areas of England with the lowest healthy life expectancy are economically inactive due to long-term sickness or disability.

Smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, and harmful alcohol use are leading risk factors driving this high burden of preventable ill health and premature mortality., All are socioeconomically patterned and have multiple, interrelated causes. People’s ability to adopt healthy behaviours is strongly shaped by the circumstances in which they live. That includes the education and support they receive in their early years, the resources they have to buy healthy food, the shops in their local communities, and whether there are green spaces and safe streets to be physically active in. There are also strong commercial factors at play, including the relative expense and availability of healthy and unhealthy foods, alcohol, and tobacco, and the ways in which they are advertised and promoted. These ‘wider determinants of health’ therefore act in both direct and indirect ways, through complex causal systems, to influence how populations and individuals are exposed to different risk factors.,

COVID-19 has exposed the consequences of government and wider society failing to act ambitiously enough to address the nation’s poor health., Our obesity rates – the highest in Europe – left the UK particularly vulnerable to poor outcomes from the virus and contributed to high death rates. Likewise, people with type 2 diabetes and hypertension (conditions linked to poor diet, obesity, and physical inactivity) are significantly more likely to die from COVID-19. For people younger than 65, the COVID-19 mortality rate was almost four times higher in the most deprived areas of England than in the least deprived during the first two waves of the pandemic, partly due to a higher burden of preventable poor health.

Government interventions to address the leading risk factors

Government has signalled its intention to act to reduce inequalities and improve health. It has promised to ‘level up’ the country and committed to extend healthy life expectancy by 5 years by 2035, while narrowing the gap between the richest and poorest., It has also set ambitious targets for some risk factors, including to go ‘smoke-free’ by 2030 and halve childhood obesity while reducing inequalities., Based on current trajectories, these targets will be missed.,,

With a new Office for Health Promotion and Disparities (OHID) and a ‘health disparities’ white paper expected from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in 2022, there is an opportunity for more cross-government action on health. This must address the breadth of factors that affect people’s exposure to ill health. There are signs the public would support a shift in approach. Recent Health Foundation/Ipsos MORI polling – conducted between 25 November and 1 December 2021 – found only 1 in 5 (18%) people in England agree that the government has the right policies in place to improve public health, while nearly half (46%) disagree. The polling also suggests strong public support for government action to address health inequalities, with the majority agreeing it is important that the government addresses health differences by income (75%), geographical area (72%), education level (69%) and ethnicity (65%).

A population-level approach

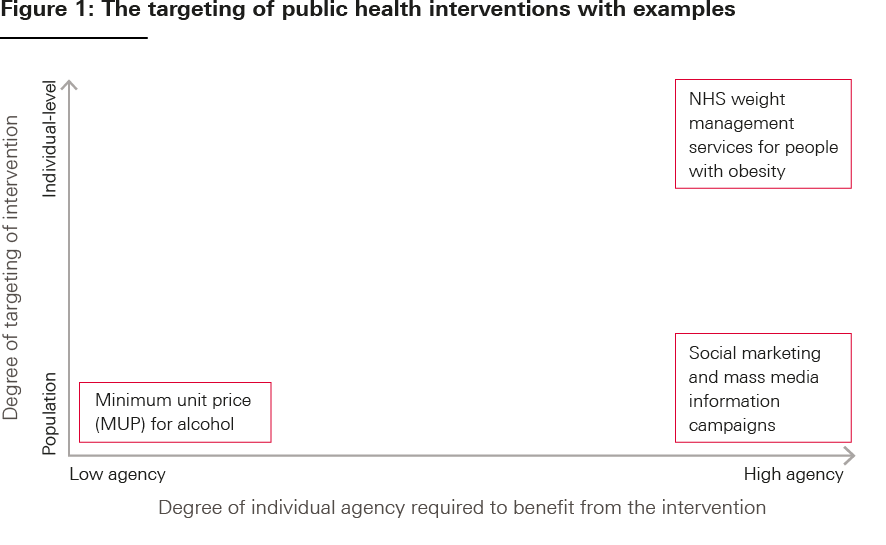

Public health interventions can be viewed along two continuums (Figure 1). Along one, population-level approaches and those targeting individuals lie at the two extremes. The other captures the level of personal resources or ‘agency’ needed for individuals to benefit from interventions. Examples of higher agency, individual-level interventions include educational classes, apps that provide people with rewards and advice to incentivise healthy eating,, and counselling services. Examples of low-agency, population-level interventions include minimum unit pricing for alcohol, regulations to restrict marketing and advertising of unhealthy food, and taxes aimed at encouraging reformulation of unhealthy products.

While important as part of a multi-component approach, interventions that rely on high levels of individual agency will have limited impact in isolation. Unless carefully targeted and tailored to those most in need of support, they can also widen inequalities. This is because more affluent individuals are more likely to have the necessary personal resources – or agency – required to benefit. For example, following referral to an exercise or healthy eating class, a person will have to identify that they have a problem, see a health professional, get a referral, travel to the class, understand and be able to act on the advice provided, and sustain a change in their behaviour over the long term. With potential for attrition at each step, this will be far easier for those who have more time, money and fewer competing stresses in their lives. By contrast, population-level interventions that rely on non-conscious processes and impact everyone – such as fiscal measures, reformulation, and marketing restrictions – are generally more likely to be both effective and equitable.,,,

Diagram adapted from: Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. PLoS Med 13(4); 2016 (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990).

It is not, however, a simple case of either/or. To reduce exposure to risk factors driving ill health and tackle inequalities, the government will still need to deploy multiple policy approaches designed to address the complex system of influences that shape behaviours. The focus needs to be on population-level policies including taxation, regulation, and public spending, which should be implemented alongside individual-level interventions to support those most in need. To be effective, policies that directly target a particular risk factor must be underpinned by wider structural interventions designed to improve the circumstances in which people live – reducing factors such as poverty and poor housing, and making it easier for people to adopt healthy behaviours.

This report explores national government policy approaches directly targeting smoking, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol use. We begin by providing an overview of recent trends in these risk factors, then summarise recent key targets and policies put forward for each by the UK government in England. We analyse national level policies introduced or proposed by government between 2016 and 2021, including policy aims, approaches, and other factors (see Appendix 1 for more details). Based on this review, we assess the government’s current policy position and point towards priorities for the future.

* In the government’s 2019 prevention green paper, Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s, an ambition was announced to go ‘smoke-free’ by 2030 (defined as smoking rates of 5% or less).

Trends in smoking, diet, physical activity and alcohol use

The risk factors driving ill health often overlap and share many common determinants and health impacts. This section outlines key trends and health impacts for each risk factor individually. We describe the socioeconomic inequalities that exist for each, focusing on differences by level of deprivation. Other inequalities relating to ethnicity, gender and age also exist but are not covered in this report.

Smoking

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable ill health and death in England, and a significant contributor to inequalities in life expectancy. It puts people at high risk of developing cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases,, and was responsible for nearly 75,000 deaths and more than 500,000 hospital admissions in England in 2019.

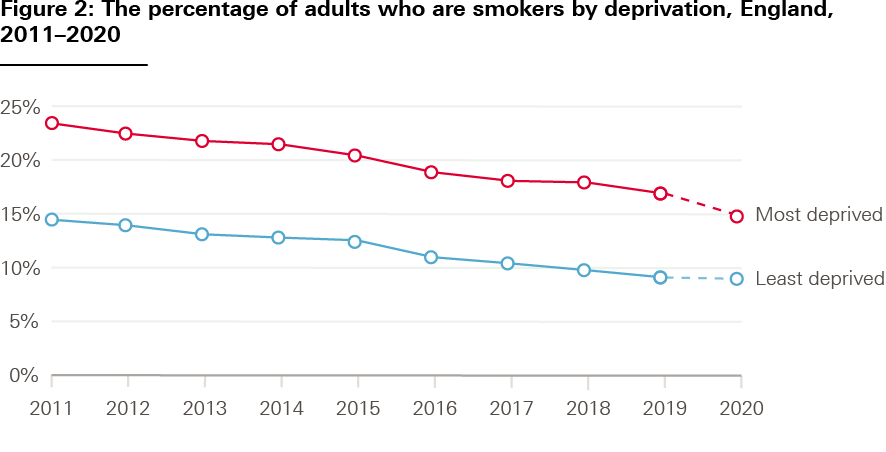

Smoking prevalence in England has almost halved from 27% to 16% over the past two decades. However, socioeconomic inequalities remain high (Figure 2). In 2019, 17% of adults in the most deprived areas smoked, compared with 9% in the least deprived. The difference is also stark for smoking during pregnancy. Nearly twice as many women smoked at time of delivery in the most deprived local authorities compared with the least deprived. Smokers working in routine and manual occupations try to quit as often as more affluent individuals, but are less likely to succeed.

It remains unclear how smoking habits changed during the pandemic, with inconsistent findings from surveys and official statistics on smoking not comparable with previous years due to changes in data collection methodology.,,,,

Source: Public Health England Outcomes Framework (based on the ONS, Annual Population Survey).

Diet

Diet is a key determinant of people’s health, with an estimated 60,000 deaths in England attributable to poor diets in 2019. As well as causing overweight and obesity, diets that are low in nutritious wholefoods and high in sugar and ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are independently associated with a range of health impacts. This includes increased risk of some cancers, hypertension, heart disease, poor oral health and premature death.,,

Fruit and vegetable consumption has been consistently low over the past decade, particularly among those living in the most deprived areas., In 2018, fewer than 3 in 10 adults in England ate the recommended five portions a day. The UK population consumes more highly processed food than any other European country,,, and consumption of free (added) sugars exceeds government guidelines, with those aged 11–18 years in 2016–2019 consuming more than double the recommended limit. The pandemic has had mixed effects on eating habits, with increases in cooking from scratch and eating healthier meals reported, but also in snacking. It has increased food poverty and insecurity, with 2.5 million people using food banks in 2020/21 – a 33% annual increase.

Physical activity

Physical activity can help to prevent and manage overweight and obesity, and protect against a range of noncommunicable diseases including cardiovascular disease and diabetes., It also has positive effects on mental health and can support social inclusion. In 2019, an estimated 10,000 deaths were attributable to low physical activity. Although the relative impact on morbidity and mortality is lower for physical activity than poor diet, increased physical activity provides additional benefits, including prevention of falls and fractures.,

The UK population is around 20% less active than in the 1960s and will be 35% less active by 2030 if trends continue. Activity fell in adults and children during the pandemic. Between May 2020 and May 2021, 61% of adults aged 16 years and older were physically active compared with 63% between May 2018 and May 2019. The percentage of physically active children fell from 47% in 2018/19 to 45% in 2020/21.

Obesity

Poor diet and physical inactivity are leading risk factors for overweight and obesity, which significantly increase the risk of developing conditions including type 2 diabetes, some cancers, cardiovascular and liver disease, dementia and mental health conditions. Obesity can also impact day-to-day living as a result of breathing difficulties, tiredness and joint pain. In 2018/19, there were 876,000 obesity-related hospital admissions.

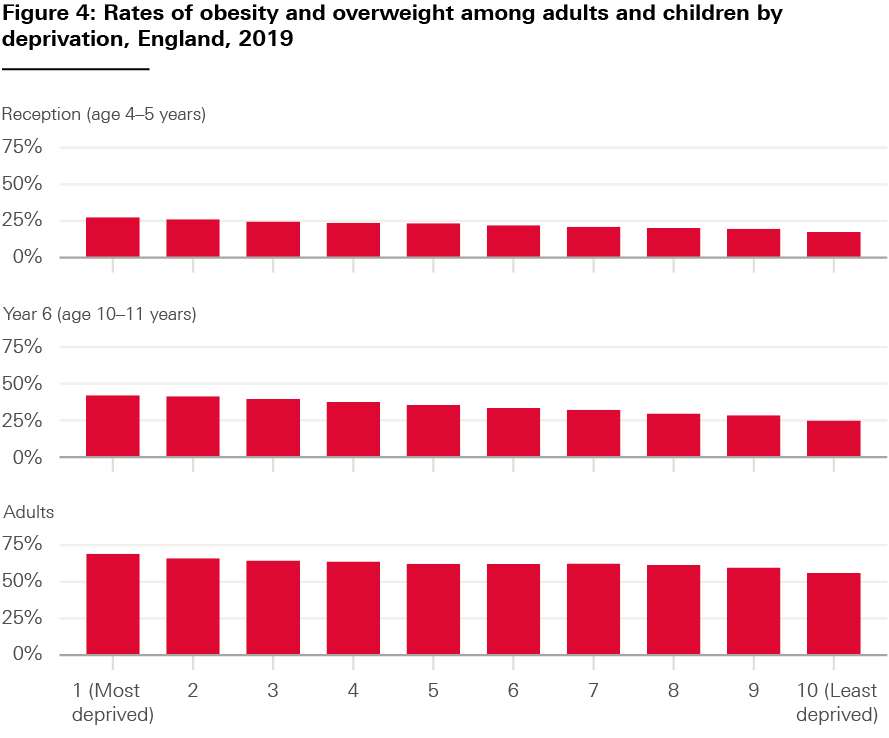

Rates of overweight and obesity among adults and children have increased over the past 20 years in England (Figure 3). There are also significant – and widening – socioeconomic inequalities, particularly for obesity rates in children (Figure 4). A sharp increase in rates of childhood overweight and obesity has been seen during the pandemic: in the space of a year, rates rose from 35% to 41% in 10–11-year-olds, and from 23% to 28% in 4–5-year-olds.

Source: NHS Digital, National Child Measurement Programme. NHS Digital, Health Survey for England.

Source: NHS Digital, National Child Measurement Programme, Sport England, Active Lives Survey.

Alcohol use

Alcohol consumption can negatively impact nearly every organ in the body, causing liver disease, heart disease, cancer, and mental health problems. It was the main reason for 320,000 hospital admissions in 2019/20, with 6,984 alcohol-specific deaths in England in 2020, a 20% increase on the previous year., Harmful alcohol use also has a significant social impact, increasing the risk of accidents, violence, child neglect and antisocial behaviour.

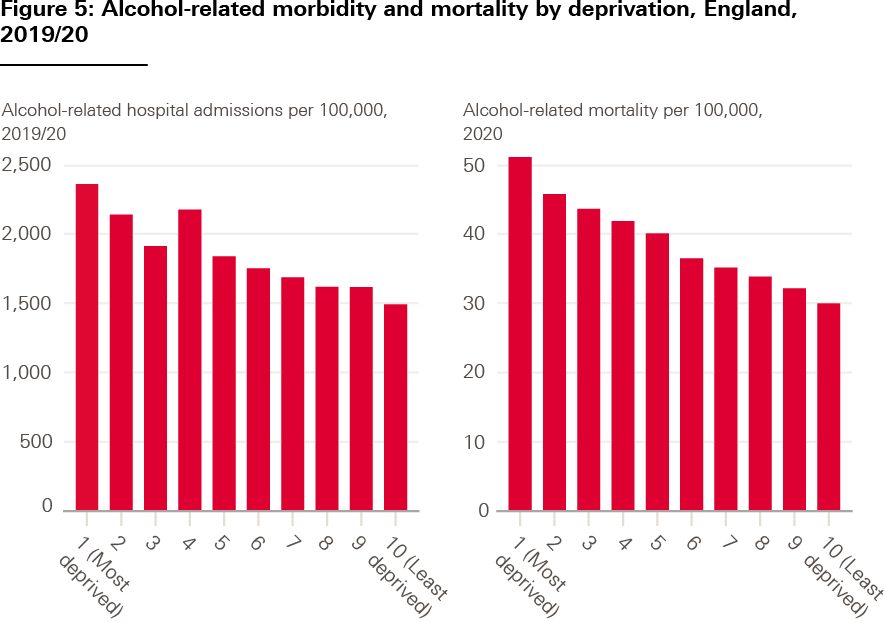

While the number of adults drinking more than the recommended 14 units per week had been falling in England, this trend has reversed over the past few years. Surveys and polling have consistently shown adults reported drinking more during the pandemic than in previous years. Although the highest fifth of earners are the most likely to drink over the recommended amount, alcohol-attributable hospital admissions and deaths are significantly higher for adults living in the most deprived areas (Figure 5)., Possible explanations include the presence of multiple risk factors, more high-risk drinking behaviours such as binge drinking, and poorer access to alcohol treatment and support in more deprived areas.,

Source: OHID fingertips, local alcohol profiles.

† For 2020/21, data were collected from a sample of children and weighted to estimate national obesity prevalence, rather than collected for all children as in previous years. Investigations by NHS Digital concluded that the 2020/21 data are representative of the population and comparable to previous years.

Addressing the leading risk factors for ill health in England: Review of the UK government’s policy

Policies proposed by government in England since 2016 to address smoking, diet, physical activity and harmful alcohol use are summarised in Tables 1–4. Only some of these policies have been implemented, and policies in each area are linked to a mix of specific and overarching government targets (Box 1). Wider government targets have also been set that necessitate action on these risk factors – including a commitment to extend healthy life expectancy by 5 years by 2035, while narrowing the gap between the richest and poorest.

Policies on targeted risk factors also interact with other national policy and political decisions that shape social, economic, and environmental factors influencing people’s ability to adopt healthy behaviours., This includes, for example, spending decisions relating to public health, social security and the NHS; funding for local government services, such as housing; and economic decisions relating to taxation and pricing.

Box 1: National targets for each leading risk factor

|

Target |

Government strategy |

Responsible body |

|

|

Smoking |

Ambition to go ‘smoke-free’ by 2030, defined as a smoking prevalence of less than 5% |

DHSC and Cabinet Office green paper: Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s (July 2019) |

DHSC and Cabinet Office |

|

Reduce smoking prevalence among adults from 15.5% to 12% or less by the end of 2022 |

DH Tobacco Control Plan for England (July 2017) |

DHSC; Public Health England (PHE) (now OHID); NHS England (NHSE); local systems (trusts/CCGs/LAs) |

|

|

Reduce the proportion of 15-year-olds who regularly smoke from 8% to 3% or less by the end of 2022 |

DH Tobacco Control Plan for England (July 2017) |

DHSC; PHE (now OHID) |

|

|

Reduce inequalities in smoking prevalence between those in routine and manual occupations and the general population |

DH Tobacco Control Plan for England (July 2017) |

DHSC; PHE (now OHID); local systems: LAs/CCGs (now integrated care systems (ICSs)) |

|

|

Reduce prevalence of smoking in pregnancy from 10.7% to 6% or less by the end of 2022 |

DH Tobacco Control Plan for England (July 2017) |

DHSC; PHE (now OHID); NHSE; local health systems |

|

|

Physical activity |

Ensure all children and young people have access to at least 60 minutes of physical activity every day (30 minutes at school and 30 minutes outside school) |

School Sport and Activity Action Plan (July 2019) |

Department for Education (DfE); Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS); DHSC |

|

Childhood obesity |

Halve childhood obesity by 2030 and significantly reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030 |

Tackling obesity: government strategy (July 2020) Childhood obesity: a plan for action, chapter 2 (June 2018) |

DHSC |

|

Harmful alcohol use |

No national targets have been set to reduce harmful alcohol use |

||

Smoking policy

Since the 1970s, the UK government has adopted a mix of population-level tax and regulatory policies alongside information campaigns and cessation services supporting individuals to quit smoking. Regarded as a global leader in tobacco control, the UK produced its first comprehensive tobacco strategy in 1998 and was one of the first countries to introduce smoke-free laws to protect people from secondhand smoke in public places and vehicles., Measures such as plain packaging and health warnings on packs have been introduced, and tobacco affordability has been reduced through escalating duty rates. Public support for government intervention to limit marketing and availability of tobacco is also high and has grown over time.,

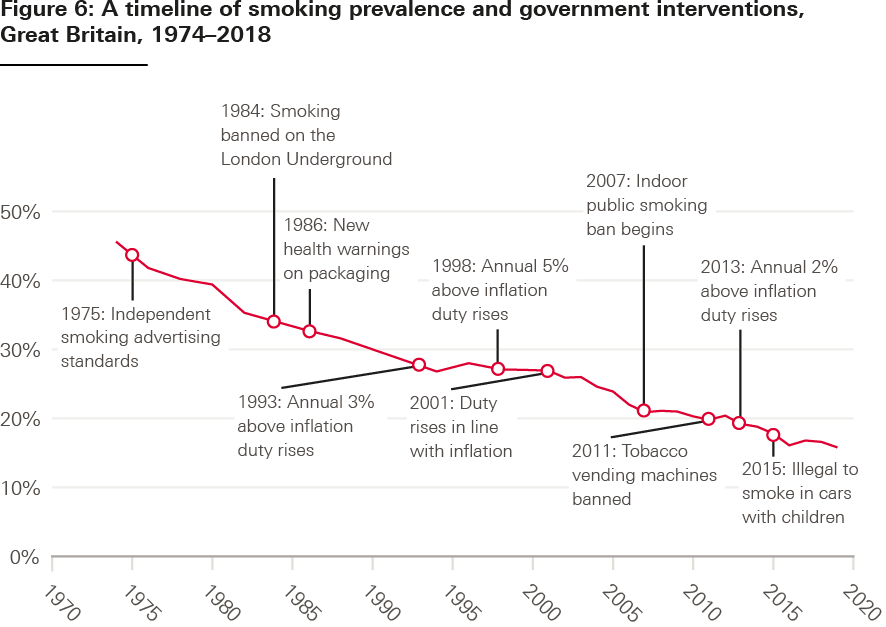

While smoking rates have remained higher among those who are more disadvantaged, including those working in routine and manual occupations, overall smoking rates declined significantly since the government began to take action – from 46% in 1974 to 16% in 2019 (Figure 6).,

Source: ONS, Adult smoking habits, Health Foundation policy navigator and ASH: Key dates in the history of anti-tobacco campaigning and Timeline of tobacco tax increases in the UK.

Notes: Only results from 2000 are weighted, pre-2000 estimates are only available every 2 years.

The government’s most recent tobacco control plan for England (2017) did not extend this previous focus on national legislation and regulation, instead shifting towards individual-level interventions such as providing guidance to support smokers to quit. The plan set a range of targets designed to achieve the government’s vision of a ‘smoke-free generation’ in which adult smoking rates are 5% or lower. Specific targets were set for 2022 to reduce smoking prevalence among adults from 15.5% to 12% or less, and to reduce prevalence among people in routine and manual occupations, pregnant women, and 15-year-olds.

The interventions that support these targets are broad and focus on information provision – including promises to monitor trends, update national guidance and train health professionals to provide stop-smoking support. While there was a commitment to maintain high tobacco duty rates and make the prison estate in England smoke-free, no new tobacco regulations were introduced in the 2017 plan. Since publication of a 2018 delivery plan, which included some detail of progress against the 2017 tobacco control plan targets, little information tracking progress has been published.

A number of targeted individual-level policy interventions are also outlined in the NHS Long Term Plan (2019), focused on expanding access to stop-smoking services for inpatient populations, including pregnant women and people with mental ill health. While these initiatives have potential to provide valuable targeted support for these high-risk population groups, it is unclear whether funding will be adequate to meet demand. It is also not clear how service rollout will be prioritised across NHS trusts, particularly in the context of high ongoing NHS pressures and a growing elective care backlog.

The government’s prevention green paper – Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s (2019) – appeared to pave the way for a greater level of ambition around population-level smoking policy, including fiscal and regulatory interventions. A ‘smoke-free by 2030’ target was set and the need for bold action recognised. DHSC also committed to consider a ‘polluter pays’ approach, whereby the government would legislate to make tobacco manufacturers contribute towards the cost of tobacco control. Over 2 years later, however, the government is yet to publish a response to the green paper and there is little detail on how it intends to achieve the target. In addition, the government’s updated tobacco control plan for England remains unpublished despite an original release date of July 2021.

Table 1: Summary of major policy initiatives on smoking (2016–2021)

|

Policy initiative |

Date |

Strategy |

Responsible body |

Lever |

Degree of agency and targeting |

|

‘Polluter pays’ levy on tobacco industry |

2019 |

DHSC and Cabinet Office |

Regulation (fee) |

Population-level; low agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

All people admitted to hospital who smoke offered NHS-funded tobacco treatment services by 2023/24 |

2019 |

NHSE; local health systems (ICSs) |

Service provision |

Individual-level; high agency |

|

|

Implemented? Underway. |

|||||

|

Smoke-free pregnancy pathway for expectant mothers and their partners |

2019 |

NHSE; local health systems |

Service provision |

Individual-level; high agency; targeted at high-risk groups |

|

|

Implemented? Underway. |

|||||

|

Smoking cessation offer for long-term users of specialist mental health services |

2019 |

NHSE; local health systems |

Service provision |

Individual-level; high agency; targeted at high-risk groups |

|

|

Implemented? Underway. |

|||||

|

To achieve the targets set in the 2017 Tobacco Control Plan for England (see Box 1) a number of broad commitments were made, largely relating to funding and enforcement of existing policies. These included commitments to:

|

|||||

Policy to improve diet and address obesity

The government has introduced some policies aimed at rebalancing the food environment towards healthier options. Most notably, in 2018 the government introduced a levy on sugary drinks (the soft drinks industry levy). The levy has been successful in incentivising manufacturers to reformulate their products, leading to a fall in average sugar content in soft drinks of 29%, with high public support maintained.,,, The government’s 2020 obesity strategy also featured regulatory measures aimed at restricting marketing and advertising of unhealthy foods. This included restrictions on some products high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) being marketed on TV before 9pm and a ban on paid-for advertising online; restrictions on the promotion of some HFSS products in shops; and calorie labelling measures. All are set to come into force by the start of 2023.

Despite these steps forward – and the effectiveness of fiscal and regulatory measures introduced to tackle smoking – government action on obesity is still largely focused on changing individual behaviour. A recent review of UK government obesity strategies between 1992 and 2020 showed it has tended to favour policies that depend on individuals’ motivation and ability to engage with information and advice. Few fiscal or regulatory policies have been introduced aimed at directly shaping the choices available to individuals.

A central plank of the 2020 obesity strategy was a new ‘Better Health’ information campaign, based around an NHS 12-week weight loss plan app. As childhood obesity rates climbed through 2021, the government launched a series of pilots aimed at incentivising healthier eating and providing specialised weight management services. This included a ‘Health Incentives’ app rewarding participants for behaviours, such as eating more fruit and vegetables (piloted in Wolverhampton from early 2022), and the launch of 15 specialist NHS clinics for severely obese children.,

A number of recently proposed population-level policies to improve diets have also been cast aside, with a lack of follow-up and transparency after their announcement. Despite announcing a ban on the sale of energy drinks to those younger than 16 in the 2019 prevention green paper, the policy has not been implemented. Likewise, a commitment in 2018 to consider including sugary milk drinks within the SDIL has been abandoned, with the 2020 obesity strategy making no mention of either policy.

While a white paper responding to the 2021 National Food Strategy is yet to be published, early signs are not encouraging regarding government’s willingness to implement the fiscal and regulatory interventions recommended, such as a sugar and salt reformulation tax., The latest data also indicate that the government’s 2018 national childhood obesity target – to ‘halve childhood obesity and significantly reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030’ – will be missed. In 2020, an inquiry by the House of Lords Select Committee on Food, Poverty, Health and the Environment concluded that a ‘unifying government ambition or strategy on food’ has been lacking, with a resulting lack of coordination and a dearth of coherent policies addressing interrelated issues such as poverty, food insecurity and poor health.

Table 2: Summary of policy initiatives on diet (2016–2021)

|

Policy initiative |

Date |

Strategy |

Responsible body |

Lever |

Degree of agency and targeting |

|

Sugar and salt reformulation tax A number of other recommendations were made in the NFS, outlined more fully in Table 2 (Appendix) |

2021 |

National Food Strategy (NFS) |

Commissioned by Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

Taxation |

Population-level; low agency |

|

Implemented? Government has promised to respond formally with a white paper within 6 months of the NFS’s publication. |

|||||

|

Ban on high fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) products being shown on TV before 9pm |

2020 |

DHSC |

Regulation (marketing) |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Due to be implemented from the beginning of 2023. Does not cover all media where advertising could be time restricted such as cinema and radio. |

|||||

|

Total online advertising restriction for HFSS products |

2020 |

DHSC |

Regulation (marketing) |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Due to implemented from the beginning of 2023. Does not cover brand advertising, owned content or advertising by small and medium-sized businesses. |

|||||

|

Restrictions on promotion of unhealthy food and drinks in retail outlets and online |

2020 |

DHSC |

Regulation (marketing) |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Due to be introduced from October 2022. |

|||||

|

Calorie labelling in large out-of-home sector businesses |

2020 2018 |

Tackling Obesity: government strategy; |

DHSC |

Regulation (information provision) |

Population-level, high agency |

|

Implemented? Yes, regulations come into force from April 2022 (for large businesses with 250+ employees). |

|||||

|

Front-of-pack nutrition labelling reforms (consultation) |

2020 |

Tackling Obesity: government strategy |

DHSC |

Regulation (provision of information/warnings) |

Population-level, high agency |

|

Implemented? No consultation response published. |

|||||

|

‘Better Health’ campaign |

2020 |

Tackling Obesity: government strategy |

DHSC PHE (now OHID) |

Information provision (mass media campaign) |

Population-level, high agency |

|

Implemented? Yes. |

|||||

|

Expansion of diabetes prevention programme |

2020 2019 |

Tackling Obesity: government strategy; NHS Long Term Plan |

NHS England (NHSE) |

Service provision; information |

Individual-level, high agency, targeted at high-risk groups |

|

Implemented? Yes. |

|||||

|

National Infant Feeding Survey: reinstatement |

2019 |

DHSC and Cabinet Office |

Information |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

Restricting sales of energy drinks to children younger than 16 |

2019 |

Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s; Childhood obesity: a plan for action, chapter 2 |

DHSC and Cabinet Office |

Regulation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

Primary care weight management services: Increasing access |

2020 2019 |

NHS England (NHSE); PHE (now OHID); local health systems |

Service provision |

Individual-level, high agency; targeted at high-risk groups |

|

|

Implemented? Underway. |

|||||

|

Adding milk drinks to the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) |

2018 |

DHSC |

Taxation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

Voluntary sugar reduction programme: Taking out 20% of sugar in products |

2016 |

PHE (now OHID) |

Voluntary programme |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Yes. |

|||||

|

Soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) |

2016 |

Public Health England (PHE); HM Treasury |

Taxation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Yes. |

|||||

Physical activity policy

The primary approach taken to improve physical activity has been information provision. DHSC publishes guidelines about the amount and type of physical activity people should undertake. The 2019 prevention green paper updated these guidelines for adults, alongside launching a physical activity campaign to support those living with health conditions to be more active. The government’s 2016 ‘plan for action’ on childhood obesity set a target that all children and young people should have access to at least 60 minutes of physical activity every day. This was reiterated in a Department for Education and DHSC school sport and activity action plan published in 2019. Little information has been published on progress against this target, and robust data are lacking to monitor and evaluate progress.

Beyond the role of DHSC, responsibility for increasing physical activity is split across a number of government departments: the Department for Culture, Media and Sport has overarching responsibility for sport, but physical activity is also covered by the Department for Education and the Department for Transport. As part of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s Sporting Future strategy (2015), Sport England announced £100m of funding for 12 local delivery pilots in 2017 to test new ways of encouraging communities, particularly those facing persistent inequalities, to increase their levels of physical activity. These pilots, which ran until September 2020 and were centred around a system-wide, place-based approach, do not appear to have been funded longer term or rolled out more widely.

The Department for Transport has also published a number of recent strategies designed to encourage active travel by improving cycling and walking infrastructure. This includes an investment strategy (2017) and a white paper setting out a ‘bold vision for cycling and walking’ (2020)., As part of this vision, £2bn of new funding to improve cycling and walking infrastructure was announced, as well as plans to incentivise GPs to prescribe cycling in places with poor health and low physical activity rates. In October 2021, the Net Zero strategy reiterated a target for half of all journeys in towns and cities to be cycled or walked by 2030. It is questionable whether the £2bn of new funding allotted to reach these targets is at the scale required to support a long-term shift towards active travel. Greater Manchester’s 1,800 mile cycling and walking network, for example, is estimated to cost £1.5bn on its own.,

Little has been published by government on the impact of its physical activity campaigns or GP prescribing initiatives. A recent inquiry conducted by the House of Lords National Plan for Sport and Recreation Committee found that government strategies relating to physical activity have been siloed, with cross-government work not happening at the scale required and fragmented delivery and funding systems. There has also been a focus on short-term projects and pilots, an approach that may hamper more meaningful long-term changes in activity levels.

Table 3: Summary of policy initiatives on physical activity (2016–2021)

|

Policy initiative |

Date |

Strategy |

Responsible body |

Lever |

Degree of agency and targeting |

|

New commissioning body and inspectorate: Active Travel England |

2020 |

Department for Transport |

Regulation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Yes, launched in January 2022. |

|||||

|

Incentivising GPs to prescribe cycling and building cycle facilities in towns with poor health |

2020 |

Department for Transport Primary care networks (PCNs) |

Service provision and regulation (subsidy) |

Individual-level, high agency |

|

|

Implemented? Not clear. |

|||||

|

Supporting cycling and walking infrastructure – £2bn investment |

2020 |

Department for Transport |

Funding and regulation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Yes, funding confirmed up to 2025. |

|||||

|

‘Moving Healthcare Professionals’ national programme |

2019 2017 |

Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s; Moving Healthcare Professionals |

PHE (now OHID) and Sport England |

Information (mass media/campaign) |

Individual-level, high agency |

|

Implemented? Yes. |

|||||

|

Physical activity campaign for people with health conditions |

2019 |

DHSC and Sport England |

Information (mass media/campaign) |

Individual-level, high agency |

|

|

Implemented? Not clear. |

|||||

|

Local pilots testing new ways of delivering sustainable increases in activity levels |

2017 |

DCMS; Sport England |

Funding |

Mixture of tailored interventions |

|

|

Implemented? Yes, £100m allocated over 4 years for 12 local delivery pilots (since Jan 2018). |

|||||

Policy to address harmful alcohol use

No government strategy to address alcohol harm has been published since 2012. That strategy had promised a ‘radical change in approach’ and outlined a number of population-level, low agency interventions to ‘turn the tide against irresponsible drinking’. This included minimum unit pricing for alcohol, banning multi-buy alcohol promotions in shops, and regulating to ensure public health is considered as an objective by local authorities when making alcohol licensing decisions.

Soon after its publication, the government backtracked on all such policies. A decade on these have not been adopted, despite mounting evidence on the effectiveness of measures such as minimum unit pricing following its introduction in Scotland (2018) and Wales (2020)., Although government announced plans for a new alcohol strategy in May 2018, this was not produced. And instead of introducing measures to tackle harmful drinking in its 2019 prevention green paper, government chose to work with industry to promote low alcohol products. Alcohol does not feature as a priority as part of government’s prevention agenda, with no national targets set. No policies have been introduced in the previous 5 years other than a commitment to set up alcohol care teams in hospitals with high rates of alcohol-related admissions, and to launch ‘sobriety tags’ detecting whether offenders have broken drinking bans.,

Alcohol continues to be widely marketed – including online, on TV, in public spaces and as part of event sponsorships. This ignores evidence showing marketing directly influences alcohol consumption. While the Scottish government is planning to consult on measures to restrict alcohol marketing, no such measures are under consideration in England. Besides a recent commitment to consult on calorie labelling for alcoholic drinks and mandatory labelling of the Chief Medical Officer’s low-risk drinking guidelines, there has been a striking lack of action for something that is responsible for over 350,000 hospital admissions a year.

Table 4: Summary of policy initiatives on alcohol (2012–2021)

No national strategy to address harmful alcohol use has been produced since 2012.

|

Policy initiative |

Date |

Strategy |

Responsible body |

Lever |

Degree of agency and targeting |

|

Calorie labelling on alcoholic drinks |

2020 |

DHSC |

Regulation (for provision of information) |

Population-level, high agency |

|

|

Implemented? Consultation promised. |

|||||

|

Alcohol-free descriptor threshold increases |

2019 |

DHSC |

Regulation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Unclear. |

|||||

|

Working with industry to increase availability of alcohol-free and low-alcohol products |

2019 |

DHSC |

Voluntary programme |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? Unclear. |

|||||

|

Alcohol Care Teams (ACTs) |

2019 |

NHSE |

Service provision |

Individual-level, high agency |

|

|

Implemented? Underway/extent of rollout unclear. |

|||||

|

Minimum unit pricing for alcohol |

2012 |

Home Office |

Regulation (pricing) |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

Ban on multi-buy promotions for alcohol in shops |

2012 |

Home Office |

Regulation (marketing) |

Population-level, medium agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

|

Health as a local alcohol licensing objective |

2012 |

Home Office |

Regulation |

Population-level, low agency |

|

|

Implemented? No. |

|||||

‡ Tables 1–4 are adapted from a more detailed table summarising key government policies across each risk factor, included in the appendix. See Appendix 1 for an overview of the scope of policies included.

Discussion

Smoking, alcohol use, poor diet and physical inactivity drive a significant burden of morbidity and mortality in England. This burden falls unequally across the population, perpetuating health inequalities. Government progress in tackling these risk factors has been too slow in recent years, with key national targets for smoking and childhood obesity set to be missed.

An uneven approach

Our review shows that government policies implemented over the past 5 to 10 years have relied heavily on promoting individual behaviour change. Some population-level fiscal and regulatory policy measures have been proposed by government over the past decade, including minimum unit pricing for alcohol, banning sales of energy drinks to children younger than 16, and adopting a ‘polluter pays’ levy for tobacco companies. But many have been abandoned or not moved beyond consultation stage, even where there is strong evidence of their effectiveness. A significant number of implemented policies have instead focused on providing information and rolling out coaching schemes that depend on people investing considerable personal resources. This is despite strong evidence showing such interventions will have less of an impact on health, particularly among people who are more socioeconomically disadvantaged and may be less able to draw on the social, material and time assets required to benefit.

This drift towards policies focused on individual behaviour change may have occurred because they are deemed more politically acceptable and easier to implement than those addressing population-level drivers. It is simpler to provide information and services to individuals than it is to design and deliver policies aimed at altering the environmental conditions and commercial influences shaping people’s behaviour. While there are signs that public opinion has shifted due to the pandemic, political, ideological, commercial and cultural factors have historically acted as barriers to the adoption of population-level policies in England. Public, media and political discourse about health and risk factors for ill health have been dominated by notions of personal responsibility, individual choice and the primacy of free markets, alongside an aversion towards policies deemed to be ‘nannying’.,,

The strength of the government’s approach has also been uneven across risk factors. Action to tackle harmful alcohol use in England has been particularly weak. Government effectively intervened to protect public health by escalating tobacco duty, but has avoided similar action for alcohol, with the alcohol industry lobbying successfully against the introduction of policies to modify prices and marketing.,,, A TV watershed and online ban are set to be introduced by the start of 2023 for some products high in fat, salt or sugar, but alcohol products are not included in these restrictions.

In relation to both alcohol and food policy, governments have tended to avoid more deterrence-based, interventionist approaches. Instead, they have often trusted those responsible for producing harmful products to help improve public health voluntarily – regardless of possible conflicts of interest, such as the food industry’s profits from increased sales of ultra-processed food. The Public Health Responsibility Deal – a public–private partnership launched by the government in 2011 that relied on voluntary action by commercial organisations – is an example of this approach. As with other such agreements based on industry self-regulation, the responsibility deal has proven to be largely ineffective.

The strong influence of corporations over the policymaking process is likely to be a key factor underlying this uneven approach. Unlike for tobacco control, no WHO Framework Convention exists to set limits on the alcohol or food industry’s influence. This is despite manufacturers of harmful food and drink exhibiting similar strategies to the tobacco industry to undermine government action. A number of studies have demonstrated how the alcohol industry employs sophisticated tactics to promote mixed messages and misinformation about alcohol harms that negatively impact consumer understanding., There is also evidence showing parts of the food industry engage in activities to prevent or delay effective policies for dietary change. These practices have presented barriers to the implementation of evidence-based policies, impeding government progress and allowing messages about unhealthy food and drink to be dominated by large corporations. A 2014 investigation into the consultation on minimum unit pricing for alcohol, for example, uncovered records of industry meetings with government officials that led to the policy’s abandonment.

There are some signs that businesses are starting to recognise the need to consider their impacts on health. Investors are increasingly interested in encouraging corporations to support positive health outcomes. One example is the recent health-related shareholder resolution filed at the supermarket Tesco, which agreed to boost sales of healthier food and drinks in response to investor pressure coordinated by ShareAction. There have been subsequent ripple effects across the retail industry, with a further shareholder resolution on health recently filed at Unilever.

Alongside the role of commercial interests, recent analyses have highlighted inadequate political leadership and governance, as well as a perceived lack of public demand for policy action, as further reasons underlying the government’s failure to consistently implement evidence-based policies.,

Disjointed policymaking

Disjointed policymaking is evident across all risk factors. Policy decisions have been taken that undermine many of the government’s own health improvement targets. This includes cutting the public health grant to local authorities by 24% in real terms between 2015/16 and 2021/22. Spending on stop-smoking and tobacco control services fell by a third over this time. During the same period, spending on mass media anti-smoking campaigns in England declined by 90% and the number of adult smokers trying to quit in the previous year fell by a quarter. Local government expenditure on resources that support people to be active – including parks, recreation and leisure centres – has also declined over the past decade.,

This comes against a backdrop of broader cuts to local public services that are key to ensuring people can live healthy lives, including housing and provision of early years services. The 2021 Spending Review settlement increases health spending, but it is weighted towards acute NHS services and does not reverse cuts to the public health grant or do enough to address rising poverty., Although the recently published levelling up white paper reiterates an ambitious commitment to reduce gaps in healthy life expectancy over the next decade, it does not come with sufficient funding to ensure action on the root causes of ill health.

Government has recently introduced policies to restrict promotion of unhealthy food and drink, including a ban on online advertising of some products high in fat, salt or sugar from 2023, yet other political decisions have the potential to undermine these. The post-Brexit trade deal with Australia, for example, failed to protect nutritional quality or prioritise health. With no requirement for health to be considered in trade negotiations, and food companies playing an influential role in World Trade Organization negotiations, there is potential for further obstruction of measures to protect health. Future free trade agreements could be struck that increase imports of unhealthy foods and impact on their pricing, availability and promotion. More generally, food marketing continues to be heavily skewed towards the least healthy options such as processed confectionery and ready meals., Unhealthy food and drink are low cost, and fast-food outlets are disproportionately clustered in low-income towns and areas., Spend on advertising these foods by big food companies is nearly 30 times what government spends on promoting healthy eating. ,,

In relation to physical activity and alcohol, economic policy decisions have often undercut efforts to protect public health. The alcohol duty escalator was abolished in 2013, and the Treasury has repeatedly frozen or cut duty for alcoholic drinks. Modelling suggests that changes in alcohol duty since 2012 have led to increased consumption, greater alcohol-related ill health, premature mortality, higher rates of alcohol-related crime and increased workplace absence than if the alcohol duty escalator had remained in place until 2015 as originally planned. Past announcements made by the Treasury have also contradicted public health messages on cigarettes and alcohol., Similarly, the freeze to fuel duty and exemptions from vehicle excise duty over the past decade have lowered the cost of driving and undermined government aims to increase active travel.

These examples of disjointed policymaking are symptomatic of wider government weaknesses in planning effectively for the long term and aligning policies across departments. Such shortcomings can be especially pronounced when addressing complex policy issues such as obesity that have multiple causes and require coordinated cross-government responses. Successive reviews have identified barriers to joined-up, long-term policymaking in the UK – including the lack of a clear national strategy at the centre of UK government; practical and organisational factors that encourage siloed working in Whitehall; and Treasury objectives and accounting that are narrowly focused and short term.,,,,

How should the government take action?

The major risk factors driving ill health and avoidable death are influenced by multiple, complex and interrelated determinants. No policy approach in isolation will be enough to address their causes and narrow inequalities. Current government policies – focused largely on providing services and campaigns designed to change individual behaviour – are insufficient for government to deliver on its key targets. With trends going in the wrong direction for many of the leading risk factors, inequalities widening, and key national targets set to be missed, it is clear that the approach taken to date has been inadequate. Polling also shows a significant proportion of the public are supportive of government action to tackle major risk factors and favour a shift in the government’s approach to public health. A more coherent, longer term vision and system-wide approach are urgently needed.

Population-level interventions that are less reliant on individual agency should form the backbone of strategies to address smoking, alcohol use, poor diet and physical inactivity. The focus should be on modifying the environments in which people live to reduce exposure to these risks and make healthy behaviours the easy option. These interventions should be accompanied by targeted support for individuals that is tailored to the needs of disadvantaged communities.

Acting on commercial determinants of health

The strong role played by the private sector in shaping environments and influencing individual behaviour must be recognised and addressed in a consistent way through government policy. Clearer limits should be set on commercial activity that harms health. Recent recommendations for how to protect net zero climate policies from corporate influence – including the use of regulations, frameworks, and criminal law to prevent corporations from misleading the public – could be adopted for companies that produce health-harming products. As with tobacco, food and drink corporations could be prevented from interfering in public health policymaking through development of clear processes and frameworks.

Government could also do more to encourage the positive role that corporations can play in supporting people to adopt healthy behaviours. A clear set of expectations should be set to ensure health impacts are considered as part of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment frameworks. Here too, a similar investment framework to that used for climate reporting could be adopted for health, based on the pillars of worker health; consumer health (via products and services produced); and community health (via impacts on the local environment). In line with this framework, clear guidelines could be developed to help strengthen companies’ health-related disclosures and drive more consistent, quality reporting on health impacts.

Future policy priorities

In identifying future policy priorities, government can learn from previous success in reducing tobacco use and consider how to adapt these strategies to combat poor diets, physical inactivity and alcohol use. Significant reductions in smoking have been achieved through a coordinated set of tax and regulatory measures, information supporting individuals to quit, and a muscular approach towards the tobacco industry that has restricted its previously strong influence over policymaking.

Some of the biggest immediate gains could be made by implementing price-based policies, taxes and regulations designed to decrease affordability of unhealthy food and drink, and increase access to healthier options. A number of policies have already been proposed in previous government documents that could be revisited. There is strong evidence on the effectiveness of a minimum unit price for alcohol in reducing harmful drinking and narrowing inequalities, for example. In Scotland, adoption of minimum unit pricing led to a reduction in off-trade alcohol sales of 4–5% in its initial 12 months, compared with England and Wales., These decreases were maintained through the first half of 2020, with comparable reductions in Wales following its introduction there. Building on the success of the soft drinks industry levy, the sugar and salt reformulation tax, proposed in the National Food Strategy, is another example of a policy that could be adopted as part of a wider set of measures to redesign the food environment.

Measures such as raising the age of sale for tobacco from 18 to 21 – which has potential to reduce smoking prevalence in this age group by at least 30% – could also be explored, as well as a ‘polluter pays’ levy on the tobacco industry to raise funds for tobacco control., The government can watch and learn from the comprehensive, multi-pronged approach being adopted in countries including New Zealand, which is increasing funding for stop-smoking services; acting to reduce the number of shops selling tobacco, and banning the sale or supply of tobacco to people born after a certain date.

Direct actions to address specific risk factors should be taken forward as part of a wider whole-government strategy to address the root causes of ill health, with all departments required to consider the health implications of their decisions and identify opportunities to improve health. Underpinning this should be a focus on investing in all four capitals: financial, human, social and natural., As with the approach being taken to reach net zero, a longer term view is needed to improve health, with targets, funding, evaluation metrics and regular independent reporting used to monitor and drive progress.

The costs of government inaction on the leading risk factors driving ill health are clear – for public services, the economy, and for individuals and their communities. As the country recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and seeks to build greater resilience against future shocks, now is the time to act.

References

- Marshall et al. The nation’s health as an asset: Building the evidence on the social and economic value of health. The Health Foundation; 2018 (www.health.org.uk/publications/the-nations-health-as-an-asset).

- Elwell-Sutton T, et al. Creating healthy lives. The Health Foundation; 2019 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/creating-healthy-lives).

- Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care. Work, health and disability green paper: data pack. UK government; 2016 (www.gov.uk/government/statistics/work-health-and-disability-green-paper-data-pack).

- Health and Safety Executive. Working days lost in Great Britain [webpage]. Health and Safety Executive; 2020 (www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/dayslost.htm).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Health state life expectancies, UK: 2017 to 2019 [webpage]. ONS (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/healthstatelifeexpectanciesuk/2017to2019).

- Marshall et al. Mortality and life expectancy trends in the UK: Stalling progress. The Health Foundation; 2019 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/mortality-and-life-expectancy-trends-in-the-uk).

- Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, Goldblatt P, Morrison J. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review Ten Years On. Institute of Health Equity; 2020 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Past and projected period and cohort life tables: 2020-based, UK, 1981 to 2070 [webpage]. ONS; January 2022 (www.ons.gov.uk/releases/pastandprojectedperiodandcohortlifetables2020baseduk1981to2070).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Health state life expectancies by national deprivation deciles, England: 2017 to 2019 [webpage]. ONS; March 2021 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/bulletins/healthstatelifeexpectanciesbyindexofmultipledeprivationimd/2017to2019).

- The Health Foundation. Map of healthy life expectancy at birth. The Health Foundation; January 2022 (www.health.org.uk/evidence-hub/health-inequalities/map-of-healthy-life-expectancy-at-birth).

- Cancer Research UK. Worldwide cancer incidence statistics. Cancer Research UK (www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer/incidence#ref1).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, GLOBOCAN 2018 accessed via Global Cancer Observatory (https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home).

- Welsh C E, Matthews F E, Jagger C. Trends in life expectancy and healthy life years at birth and age 65 in the UK, 2008–2016, and other countries of the EU28: An observational cross-sectional study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe; 2021 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100023).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). An overview of lifestyles and wider characteristics linked to Healthy Life Expectancy in England: June 2017 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/articles/healthrelatedlifestylesandwidercharacteristicsofpeoplelivinginareaswiththehighestorlowesthealthylife/june2017).

- IHME. United Kingdom Profile. Data from Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (www.healthdata.org/united-kingdom).

- World Health Organization. WHO Factsheets: non communicable diseases. 2021 (www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases).

- Marteau T, et al. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ. 2021;372:n332. February 2021 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7879795).

- Lee K and Freudenberg N. Addressing Commercial Determinants of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2022; 43:25.1–25.21 (https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052220-020447).

- Elwell-Sutton T, et al. ‘Chapter 3: The local health environment’ in Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer; 2018 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-local-health-environment).

- Rutter H, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602.

- Suleman M, Sonthalia S, Webb C, Tinson A, Kane M, Bunbury S, Finch D, Bibby J. Unequal pandemic, fairer recovery: The COVID-19 impact inquiry report. The Health Foundation; 2021 (https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2021- HL12).

- Atkins JL, Masoli JAH, Delgado J, Pilling LC, Kuo CL, Kuchel GA, et al. Preexisting Comorbidities Predicting COVID-19 and Mortality in the UK Biobank Community Cohort. Newman AB, editor. The Journals of Gerontology – Series A. 2020;75(11):2224–30 (https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa183).

- Public Health England. Excess Weight and COVID-19. Insights from new evidence. Public Health England; 2020 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/907966/PHE_insight_Excess_weight_and_COVID-19__FINAL.pdf).

- Williamson E J, Walker A J, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton C E, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19- related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–6 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4).

- Tinson A. What geographic inequalities in COVID-19 mortality rates and health can tell us about levelling up. The Health Foundation; 2021 (www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/what-geographic-inequalities-in-covid-19-mortality-rates-can-tell-us-about-levelling-up).

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. The Grand Challenges. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy; 2019 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy-the-grand-challenges/industrial-strategy-the-grand-challenges).

- HM Government. Levelling Up the United Kingdom. HM Government; 2022 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052064/Levelling_Up_White_Paper_HR.pdf).

- Cabinet Office and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document; July 2019 (www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s-consultation-document).

- HM Government. Childhood obesity: a plan for action: Chapter 2. HM Government; 2018 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/718903/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action-chapter-2.pdf).

- Elwell-Sutton T, et al. Creating healthy lives. The Health Foundation; 2019 (www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/creating-healthy-lives) (p 10).

- Cancer Intelligence Team, Cancer Research UK. Smoking prevalence projections for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, based on data to 2018/19. Cancer Research UK; February 2020.

- The Lancet. Childhood obesity: a growing pandemic. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022;10(1):1 (www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(21)00314-4/fulltext).

- HM Government. Levelling Up the United Kingdom. February 2022 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052064/Levelling_Up_White_Paper_HR.pdf).

- Merrifield K, Nightingale G. A whole-government approach to improving health. The Health Foundation; 2021 (https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2021-HL13).

- Health Foundation. Public perceptions of health and social care (November–December 2021). February 2022 (www.health.org.uk/publications/public-perceptions-of-health-and-social-care-november-december-2021).

- Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. PLoS Med. 2016;13(4) (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990).

- Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Press release: New pilot to help people eat better and exercise more; October 2021 (www.gov.uk/government/news/new-pilot-to-help-people-eat-better-and-exercise-more).

- Devlin H. NHS Food Scanner app will use barcodes to suggest healthier eating choices. The Guardian; January 2022 (www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jan/10/nhs-food-scanner-app-will-use-barcodes-to-suggest-healthier-eating-choices).

- Jochelson K. ‘Nanny or steward? The role of government in public health.’ Public Health. 2006;120:1149–1155.

- Marteau T, White M, Rutter H, Petticrew M, Mytton O, McGowan J, Aldridge R. Increasing healthy life expectancy equitably in England by 5 years by 2035: could it be achieved? The Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2571–2573 (www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2819%2931510-7).

- Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2013;67:190–3.

- Public Health England. Health Profile for England 2021: Summary 16 – Inequalities in Risk Factors [webpage]. Public Health England (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profile-for-england/hpfe_report.html#summary-16---inequalities-in-risk-factors).

- Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, Lopez AD. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. The Lancet. 2006;368(9533):367–70.

- ASH. Smoking, the heart and circulation. ASH; 2021 (https://ash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Smoking-Heart.pdf).

- Cancer Research UK. Lung Cancer Risk [webpage]. Cancer Research UK (www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer/risk-factors).

- NHS Digital. Statistics on Smoking, England 2020; December 2020 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2020).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) Adult Smoking Habits in the UK: 2019. ONS; July 2020 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2019).

- Public Health England (based on ONS, Annual Population Survey). Public Health Outcomes Framework. C18 – Smoking Prevalence in adults (18+) – current smokers (APS); 2022. (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework/).

- Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). During the pandemic smoking in pregnancy fell below 10% for the first time since records began BUT Government still not on track to reach target of 6% or less by 2022. ASH; 2021. (https://ash.org.uk/media-and-news/press-releases-media-and-news/during-the-pandemic-smoking-in-pregnancy-fell-below-10-for-the-first-time-since-records-began-but-government-still-not-on-track-to-reach-target-of-6-or-less-by-2022).

- Public Health England. Local Tobacco Control Profiles. Public Health England; December 2021. (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/tobacco-control/data).

- Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). Health Inequalities and Smoking; 2019 (https://ash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ASH-Briefing_Health-Inequalities.pdf).

- NHS Digital. GP Patient Survey. (www.gp-patient.co.uk).

- Jackson S E, Beard E, Angus C, Field M, Brown J. Moderators of changes in smoking, drinking and quitting behaviour associated with the first COVID-19 lockdown in England. Addiction. 2021;1–12 (https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15656).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) monitoring tool. OHID (https://analytics.phe.gov.uk/apps/covid-19-indirect-effects).

- Health Foundation analysis of Understanding Society. Covid-19 Survey; October 2021 (www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/topic/covid-19).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Smoking prevalence in the UK and the impact of data collection changes: 2020; December 2021. (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/drugusealcoholandsmoking/bulletins/smokingprevalenceintheukandtheimpactofdatacollectionchanges/2020).

- GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; 2019 (www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(19)30041-8/fulltext).

- Vandevijvere S, et al. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes Rev. 2019;20(2):10–19 (https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12860).

- Fiolet T, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;360:k322 (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k322).

- Srour B, et al. Ultraprocessed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé) BMJ. 2019;365:l1451 (www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1451).

- Chen X, Zhang Z, Yang H, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr J. 2020;19:86 (https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-020-00604-1).

- Public Health England. NDNS: results from years 9 to 11 (combined) – statistical summary. Public Health England; 2020 (www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-combined-statistical-summary).

- Public Health England (based on Active Lives, Sport England). Public Health Outcomes Framework: C15 – Proportion of the population meeting the recommended ‘5-a-day’ on a ‘usual day’ (adults); 2021 (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework).

- NHS Digital. Health Survey for England 2018; 2019 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2018).

- House of Lords Select Committee on Food, Poverty, Health and the Environment. Hungry for change: fixing the failures in food; 2020 (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5801/ldselect/ldfphe/85/85.pdf).

- Timmins G, O’Hare R. Urgent action needed to reduce harm of ultra-processed foods to British children; 2021 (www.imperial.ac.uk/news/223573/urgent-action-needed-reduce-harm-ultra-processed).

- Rauber F, Louzada MLDC, Martinez Steele E, et al. Ultra-processed foods and excessive free sugar intake in the UK: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027546 (doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027546).

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling programme Years 9 to 11 (2016/2017 to 2018/2019); 2020 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/943114/NDNS_UK_Y9-11_report.pdf).

- Public Health England. Health Profile for England; 2021 (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profile-for-england/hpfe_report.html).

- The Trussell Trust. Trussell Trust data briefing on end-of-year statistics relating to use of food banks: April 2020–March 2021; 2021 (www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/04/Trusell-Trust-End-of-Year-stats-data-briefing_2020_21.pdf).

- Public Health England. Health matters: physical activity – prevention and management of long-term conditions; 2020 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-physical-activity/health-matters-physical-activity-prevention-and-management-of-long-term-conditions#wider-role-and-benefits-of-physical-activity).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical Activity. WHO; 2020 (www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity).

- Public Health England. Everybody active, every day. Public Health England; 2014 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/374914/Framework_13.pdf) (p 7).

- Sherrington C, Fairhall N, Kwok W, et al. Evidence on physical activity and falls prevention for people aged 65+ years: systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:144 (https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01041-3).

- LaMonte M J, Wactawski-Wende J, Larson J C, et al. Association of Physical Activity and Fracture Risk Among Postmenopausal Women. JAMA Netw Open; October 2019 (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2753526).

- Public Health England. Guidance: Physical activity: applying all our health; 2019 (www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health).

- Sport England. Active Lives Adult Survey May 2020/21 Report; 2021 (https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-10/Active%20Lives%20Adult%20Survey%20May%202020-21%20Report.pdf?VersionId=YcsnWYZSKx4n12TH0cKpY392hBkRdA8N).

- Sport England. Active Lives Children and Young People Survey Academic year 2020/21; 2021 (https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-12/Active%20Lives%20Children%20and%20Young%20People%20Survey%20Academic%20Year%202020-21%20Report.pdf?VersionId=3jpdwfbsWB4PNtKJGxwbyu5Y2nuRFMBV).

- NHS. Obesity [webpage]. NHS; 2019 (www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Obesity/Pages/Introduction.aspx).

- NHS Digital. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England, 2020; 2020 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/england-2020).

- Public Health England. Obesity Profile; 2021 (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/national-child-measurement-programme).

- Newton J, Briggs A, Murray C, Dicker D, Foreman K, Wang H, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2257–2274 (https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00195-6).

- Public Health England. Local Alcohol Profiles for England; 2022 (https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/local-alcohol-profiles).

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK. ONS; 2021 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/datasets/alcoholspecificdeathsintheukmaindataset).

- Commission on Alcohol Harm. ‘It’s everywhere’ – alcohol’s public face and private harm: The report of the Commission on Alcohol Harm; 2021 (https://ahauk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Its-Everywhere-Commission-on-Alcohol-Harm-final-report.pdf).

- NHS Digital. Health Survey for England 2019; 2020 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2019).

- Public Health England. Monitoring alcohol consumption and harm during the COVID-19 pandemic. July 2021 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1002627/Alcohol_and_COVID_report.pdf).

- Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2020. December 2021 (www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/alcoholrelateddeathsintheunitedkingdom/registeredin2020).