Foreword

This report looks back at what has changed in cancer care in England over the past 20 to 30 years. The aim is to consider what has worked well, or less well, and why. Importantly the purpose is to learn from the past, so that these lessons can be applied to cancer care and other conditions in the future.

To do this I have worked with colleagues at the Health Foundation to review the commitments made on cancer at a national level and the extent to which they have been achieved. I am also extremely grateful to nearly 70 colleagues who agreed to be interviewed for this project. All of them have been closely involved in the cancer agenda, but from very different angles. They include politicians, journalists, clinicians, NHS managers and those working for cancer charities. Several have had personal or family experience of cancer.

The report considers all aspects of cancer care, from prevention through diagnosis and treatment to living with and beyond cancer. This leaves one notable exception – end of life care – because I believe this merits an analysis of its own – and clearly doesn’t only apply to cancer.

For cancer management as a whole and for each step in the care pathway that a person experiences, we have considered the factors which enable and block improvement. Some clear messages emerge which I hope will be of value to ministers, national bodies and to those both lobbying for or driving change at national and local levels.

Cancer care was still in the dark ages at the start of my career, some 40 years ago. Some patients were still not being told their diagnosis, with relatives often being told rather than the patient. Even the word cancer was frequently avoided, with terms such as tumour, neoplasm, growth, a ‘little ulcer’ (always ‘little’) or other terms being used instead. As a medical student doing a locum week as a house officer, I was once asked by a consultant to tell a patient’s wife that her husband had acute leukaemia. I did my best, but that was far from good enough.

A few years later when I was considering a career in oncology, a very distinguished consultant asked me ‘why would you want to do that? Don’t they all die?’ Fatalism and nihilism among the medical profession was widespread.

Progress was undoubtedly made in the 1980s and early 1990s with evidence of the effectiveness of new treatments for some cancers, including childhood cancers, lymphomas and leukaemias, testicular cancer and breast cancer. However, the UK was slow to respond to these advances. Although cancer charities (the Imperial Cancer Research Fund and Cancer Research Campaign) provided funding for training of medical oncologists (myself included), the NHS failed to create sufficient consultant posts to employ these clinicians once fully trained. Many were forced to emigrate – to the benefit of countries like Canada, but at the expense of this country.

In the early 1990s, when I was a consultant specialising in breast cancer at Guy’s Hospital I remember being phoned by a colleague working in a district general hospital 50 miles away. He wanted advice on whether to give adjuvant chemotherapy to a 32-year-old woman with breast cancer. I asked whether the disease had spread to the axillary lymph nodes, only to be told that surgeons in that city didn’t remove any lymph nodes for analysis. Similarly, on asking about the pathological grade of the cancer, I was told that the pathologists didn’t assess the grade of a cancer. The size of the cancer had not been recorded. At Guy’s I was used to having all of this information on all patients who were referred to me. I was shocked at the difference in approach between hospitals.

This led me to work with the Thames Cancer Registry to look more widely at variations in the care given to women aged under 50 with breast cancer in south-east England. Wide variations were all too clearly apparent, despite consensus guidelines having been published in the late 1980s in the British Medical Journal.

The experts I have talked to in the development of this report agree that publication of the Calman–Hine report in 1995 was the first major wake-up call on cancer care in this country. Inspired by the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales (Ken Calman and Deirdre Hine) an expert advisory group on cancer set out the principles underlying good cancer care and the broad structure of services needed to deliver such care. However, this report had no formal government backing, nor did it come with funding. It does, however, mark the starting point for this analysis of progress. I chose 2015 as its end point, as it represents the final year of the last cancer strategy for which I was responsible, (published in 2011).

It has been a privilege to come back to the world of cancer after 4 years as Chief Inspector of Hospitals at the Care Quality Commission. This has given me the opportunity to look with fresh eyes at the challenges of whole system change and to make recommendations for delivering improvements in the NHS, both for cancers and for other conditions.

Professor Sir Mike Richards

Former National Cancer Director, 1999–2013

Timeline

1995

Calman–Hine report

Report from the Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) of England and Wales setting out the principles underlying good cancer care and the broad structure of services needed to deliver such care. No formal government backing or funding.

1996

Publication of the first Improving Outcomes Guidance

The first in a series of reports summarising what processes of care were most likely to be associated with the best outcomes for individual cancers. Written by expert advisory groups, these were funded by central government money – £10 million for each cancer – from 1997.

1997

Election of the Labour Government

Action to improve the NHS was a key Labour manifesto commitment. This included specific pledges on cancer – £10 million for implementation of breast cancer guidance and commitments on waiting times for breast cancer.

1998

Smoking Kills white paper

The first ever tobacco control strategy set a target to reduce the prevalence of smoking from 28% to 24% by 2010. This was achieved.

1999

Cancer summit at 10 Downing Street (May)

A signifier of the level of political interest in cancer, Tony Blair, then Prime Minister, convened a cancer summit, and subsequently announced a review of cancer services, plus the creation of a National Cancer Action Team ‘to raise the standard of cancer care in all hospitals’.

Appointment of the first National Cancer Director (October)

The creation of this role, and appointment of Professor Mike Richards gave clear leadership on cancer in the NHS in England.

Foundation of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Cancer

Set up to be the voice in parliament of cancer patients and their families. It campaigns on multiple issues including early diagnosis, cancer workforce and patient experience.

2000

NHS Plan (July)

Promised thousands of new beds, doctors, nurses and improved hospitals and GP premises. NHS organisations would be accountable for new waiting times targets and expected to deliver care to new national standards. Contained a promise of a comprehensive national cancer plan and £570 million over 3 years for improving cancer services.

NHS Cancer Plan (September)

Set out strategies for cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment and care. Contained detailed plans for implementation over the next 5 years, including milestones and deadlines with dates attached. Established cancer networks as a vehicle for delivering change. Significant funding attached, identified in NHS Plan.

2002

‘National survey: cancer patients’ – the first national survey of cancer patient experience

Pointed to the existence of major delays in accessing cancer treatment, and significant variation in waiting times and patient experience across the country.

2003

Extension of breast screening programme to seven rounds

Fulfilled an NHS Cancer Plan pledge to widen breast screening from age 50–65 to age 50–70 (an additional two rounds).

Introduction of liquid-based cytology for cervical screening

Fulfilled an NHS Cancer Plan pledge to improve and update the cervical screening programme.

2004

National Audit Office (NAO) report: Tackling Cancer in England, Saving more lives

Recognised that the pace of improvement in cancer services had quickened since The NHS Cancer Plan. Raised concerns about delayed diagnosis, highlighted workforce shortages, and called for more action on geographical and social inequality in access to high-quality care.

2005

NAO report: Tackling Cancer, Improving the patient journey (February)

Encouraging progress had been made since 2000 in most aspects of patient experience. However, still too much variation by geography and cancer type.

NAO report: The NHS Cancer Plan, A progress report (March)

Reported that the NHS Cancer Plan is well constructed, well regarded and delivering positive changes. Cancer networks are working well, but can be improved. Plans will be needed to update the NHS Cancer Plan.

2007

Cancer Reform Strategy

Updated the NHS Cancer Plan and acknowledged progress. Despite all this activity there has been a failure to reduce the gap in survival between comparator countries. Included four major new initiatives, on early diagnosis, survivorship, information and equalities. No additional dedicated funding.

2008

New initiatives established

Following the Cancer Reform Strategy, the National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative, National Cancer Survivorship Initiative, National Cancer Intelligence Network and National Cancer Inequalities Initiative were established.

2010

Coalition government elected

Conservative party manifesto promised action on cancer, including a ‘Cancer Drugs Fund’. They were joined in government by the Liberal Democrats.

Bowel cancer screening introduced

The bowel cancer screening programme started, initially using testing of stool samples, but with a government commitment to introducing flexible sigmoidoscopy to the programme.

2011

Cancer Drugs Fund created

Initially worth £200 million per year, this was designed to give patients access to drugs not routinely available on the NHS.

Improving Outcomes: A strategy for cancer

Landed amid plans for NHS reforms, but did not commit additional money to cancer. It promised action on screening and data, and a maintained focus on improving outcomes.

2012

Health and Social Care Act

Fundamental structural reform to the NHS, with the creation of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs). Devolved responsibility for some functions previously held by the Department of Health to new ‘arm’s-length bodies’ such as Health Education England and Public Health England.

2013

National Cancer Action Team

Disbanded and funding for cancer networks reduced.

2014

Five year forward view

Recognised cancer as a priority and promised action on prevention, faster diagnosis and better care. New models of care established, with a shift towards integration of care. Focused on how to make efficiency savings – no extra funding.

2015

NAO – Progress in improving cancer services and outcomes in England (January)

Reviewed progress since 2011. Outcomes continue to improve, but there is too much variability in outcomes and access across the country. ‘Data gaps’ remain, with more action needed to improve cancer data, particularly around stage at diagnosis.

Independent cancer task force report – Achieving World Class Cancer Outcomes: A strategy for cancer 2015–2020

Written independently but adopted in full by NHS England, the 96 recommendations include a focus on prevention and early diagnosis. Called for investment in new infrastructure and the creation of cancer alliances at an estimated cost of £400 million a year.

Executive summary

This report offers an account of what has changed since 1995 in cancer services in England. It assesses the NHS Cancer Plan and the two subsequent strategies, from 2000 to 2015. We present data on the progress in treatment and outcomes of cancer services (not including end of life care). We also explore what factors might have contributed to success and failure in how cancer services developed. In the absence of formal evaluation of the National Cancer Programme between 1995 and 2015, we conducted interviews with nearly 70 people involved in creating and implementing the cancer programme, to understand what these national strategies were designed to do and how they worked in practice. These included senior clinicians, managers, civil servants and researchers, from the Department of Health, the NHS and charities.

Areas where progress has been made

- Significant improvements have been made on mortality, survival rates and patient experience of cancer care over the past 20 years.

- Progress can almost certainly be attributed to a combination of better service organisation and the introduction of more effective treatments.

- Delivery of care by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) was the exception rather than the rule 25 years ago. This has now changed radically, though not all teams are functioning optimally.

- The cancer workforce has expanded considerably. Cancer nurse specialists have become the norm, and patients are more likely to receive treatment in specialist centres, where appropriate. But as demand has grown, workforce shortages have re-emerged, particularly in diagnostic specialties.

- Technology for cancer care has improved markedly, both in relation to diagnostics (eg magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission/computerised tomography (PET/CT) and molecular markers) and new treatments (eg laparoscopic surgery, better targeted radiotherapy and new drugs).

- Data/intelligence on cancer has improved significantly. This can help monitor progress at both national and local levels, though further improvements are still needed.

- Government intervention in the form of anti-smoking legislation has contributed to a steady decline in the largest preventable cause of cancer.

- Measuring patients’ experience of cancer service is now accepted as essential to understanding the quality of care, as is the importance of people’s wellbeing after cancer treatment.

What has driven progress on cancer?

A consistent theme that emerged from many of the interviews was the creation of a broad community for change through the National Cancer Programme between 2000 and 2015. It is possible to distinguish separate components of this that, in combination, were perceived as having created a sense of momentum, particularly among clinicians.

Evidence-based guidance, intelligence and research

- Development of guidance (Improving Outcomes Guidance) for individual cancers setting out the design of services most likely to achieve good outcomes.

- Improved intelligence, including big improvements in cancer registries, the capacity to link with other datasets such as screening and hospital data, good-quality clinical audits for some cancers, and the development of cancer profiles giving comparative information at primary care trust (PCT)/CCG, GP practice and network levels.

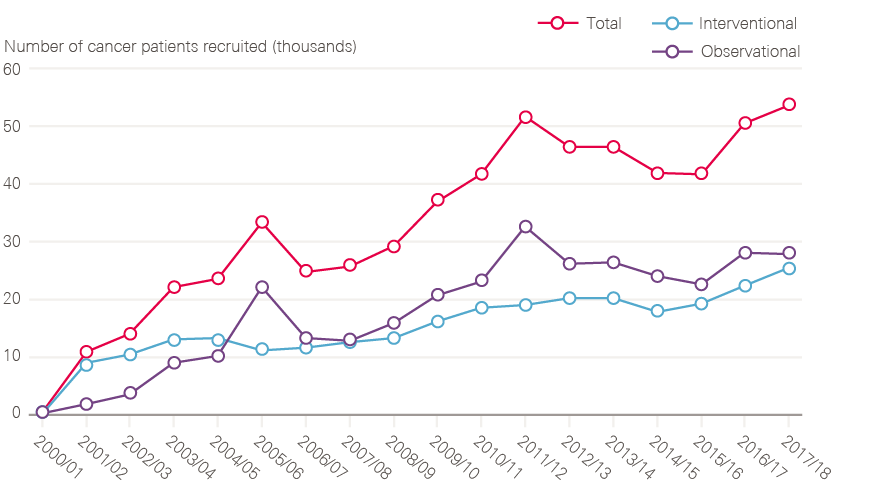

- Establishment of cancer research networks, mapped onto the service networks, leading to a tripling of patients entering nationally approved clinical trials.

Infrastructure to make change locally, with support to build capability

- Establishment of cancer networks, which were funded with permanent staff, brought together commissioners, clinicians, managers and patients across organisational boundaries to oversee the local/regional implementation of national strategy, and plan improvement.

- Cancer Services Collaborative (a centrally funded programme using quality improvement methods) worked with clinicians and managers within networks and trusts to redesign services. Cancer networks also had their own development programme to share learning.

- The National Cancer Peer Review Programme (with patients as part of the team) ensured compliance with the recommendations in the Improving Outcomes Guidance, and the results were published to boost transparency.

Adequately supported leadership

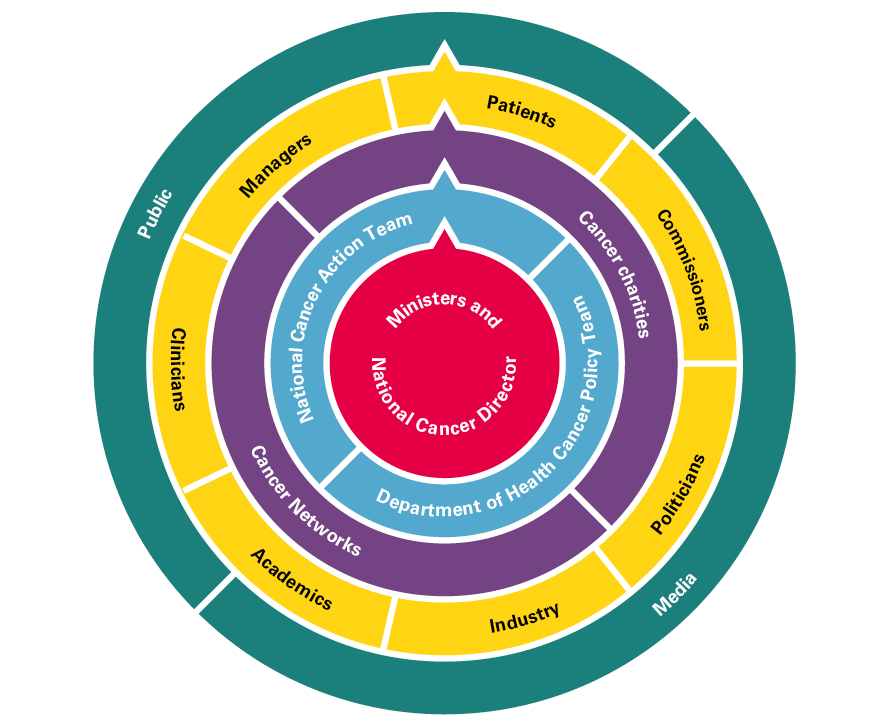

- A full-time National Cancer Director from 1999, supported by a national team in the Department of Health, an outward-facing National Cancer Action Team and a dedicated team overseeing cancer screening.

- Clear direction set out in comprehensive cancer plans/strategies and a comprehensive overview of the quality of care being delivered. Data from registries, audits, NHS trusts, screening and research all flowed into the National Cancer Action Team.

- Extensive engagement with key stakeholders and development of a strong cancer community (comprising clinicians, managers, patients, cancer charities, professional colleges and societies, industry and researchers).

- High-level political support, and a strong media focus on cancer, reflecting public interest, fear and concern about cancer.

- Targets for cancer waiting times, supported by intensive support to trusts which were struggling to achieve them.

Adequate funding, and some increases in workforce

- Dedicated funding for some aspects of cancer (especially in the early years of the programme).

- Appraisal by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of new cancer drugs, with (from 2001) a funding directive to PCTs to make the drugs available within 3 months of a positive appraisal.

- Expansion of the workforce in the early years of the programme, and the introduction of new workforce models (eg the four-tier model for radiographers to enable expansion of breast screening).

Areas where there has been less progress

Despite these improvements, England’s 5-year survival rates (and those of the UK) have not caught up with other comparable countries. With the exception of breast cancer, the gap has not narrowed, as other countries have also improved. The NHS Cancer Plan promised cancer services that would be the best in Europe and that cancer care would never again fall behind. This represents the ‘unfinished business’ that is the theme of this report, and a number of factors have been identified as possible explanations for this.

- The focus in the early years of the programme was largely on secondary and tertiary care. Although the importance of primary care was recognised in both the Calman–Hine report (1995) and the NHS Cancer Plan (2000), it was not clear what actions needed to be taken.

- Until the early 2000s very little health services research had been done on primary care and cancer. This is now an active field of research with high-quality researchers, often funded by the Department of Health and Social Care/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Cancer Research UK. This research has, for example, led to the development of evidence-based guidelines on which patients should be investigated or referred to hospital with possible cancer.

- In the early phases of the National Cancer Programme, too little emphasis was placed on improving the rate of early diagnosis, which accounts, at least in part, for the poor survival rates in England, relative to survival rates in other comparable countries.

- It took time to generate an adequate evidence base and use it to change attitudes. In the early years of the programme, doubts were cast on the validity of the international cancer survival comparisons, as cancer registries were undoubtedly missing some patients. Cancer registration in England is now among the best in the world, however survival rates remain comparatively poor.

- In the late 1990s some cancer experts doubted that delays of a few months in diagnosis could impact on survival rates significantly. This has now changed, as a result of being able to link cancer data with hospital and screening data. This has demonstrated the magnitude of late diagnosis, and its impacts on survival. There is now almost universal consensus on the importance of early diagnosis of symptomatic patients.

- Research has suggested that the gatekeeping model of the NHS (where GPs predominantly have responsibility for providing patients with access to diagnostics and hospital care) may deter patients with possible symptoms of cancer from seeking advice from their GP and may deter GPs from investigating or referring patients.

- New models for access to diagnosis are now being tested, but have not yet been widely implemented.

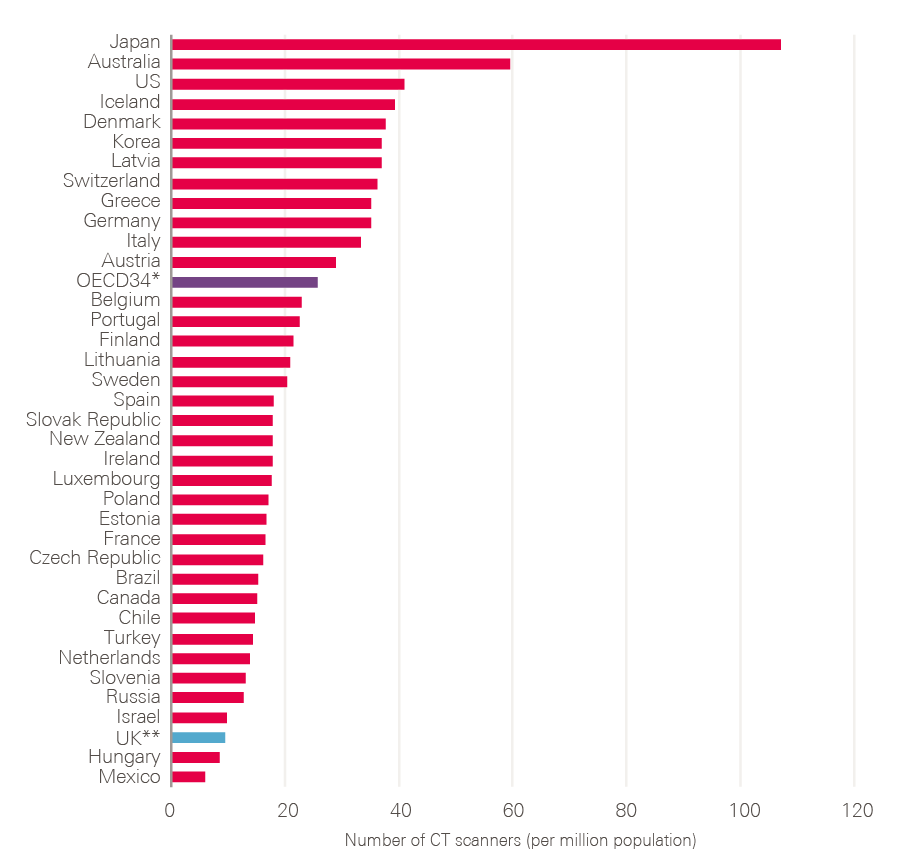

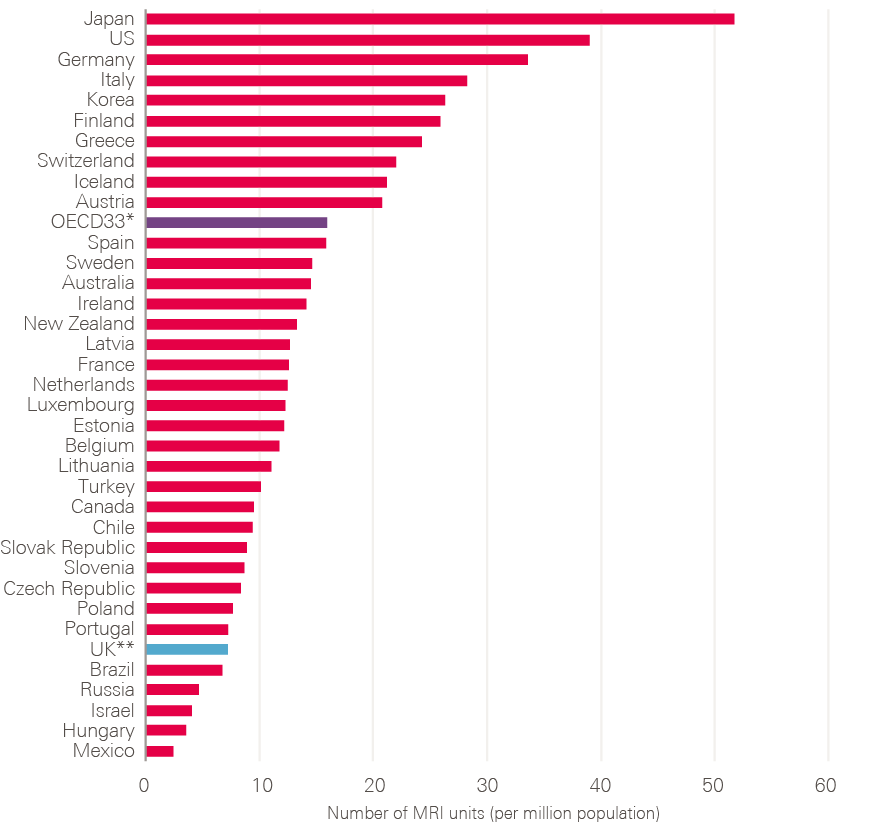

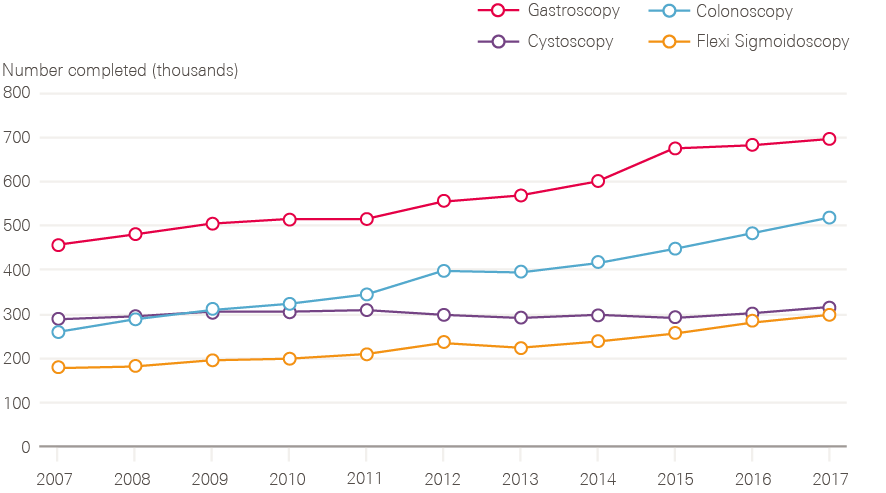

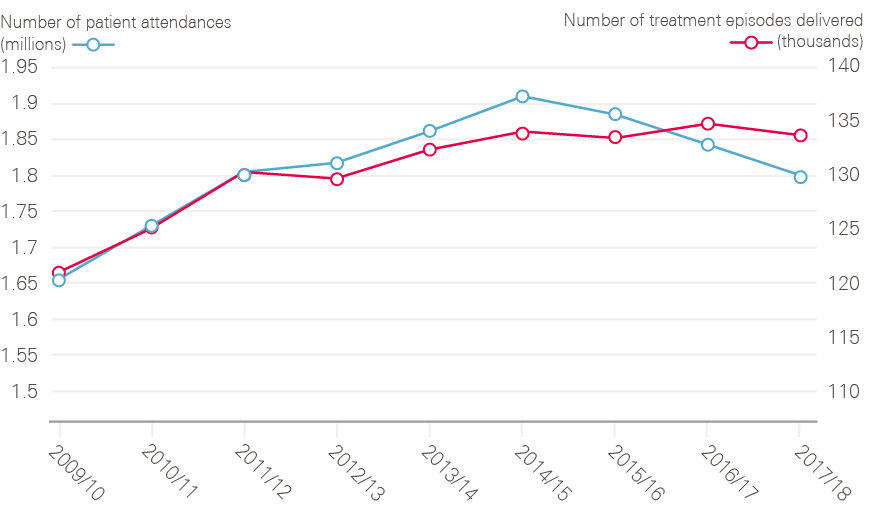

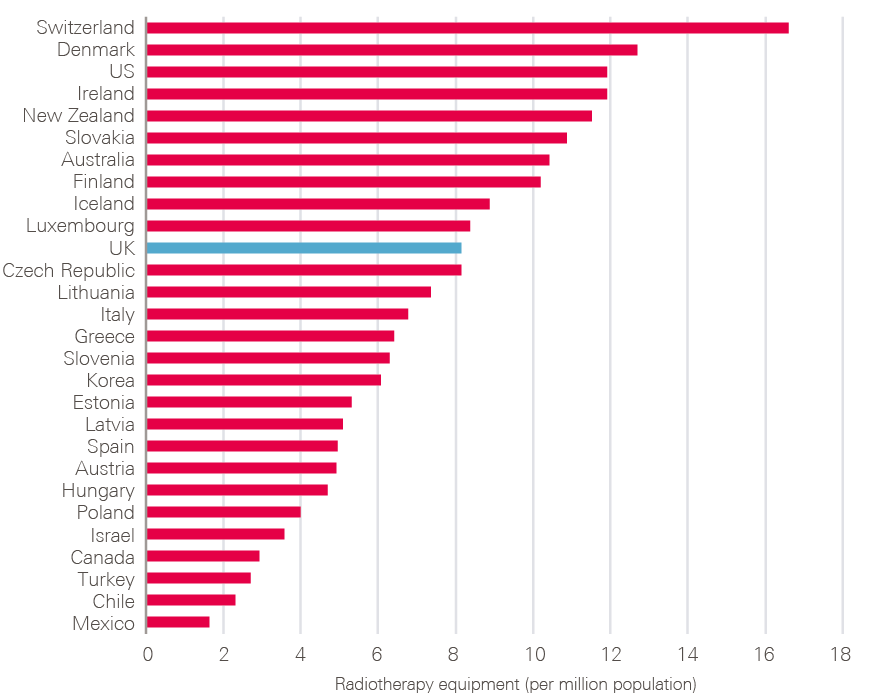

- Delivering the increases needed in the cancer workforce has been consistently difficult. Diagnostic capacity in particular (endoscopy, imaging and pathology) has not expanded to meet demand and lags behind that in other comparable countries, creating a barrier to early diagnosis. Financial incentives to encourage trusts to increase and maintain their diagnostic capacity have, to date, been inadequate.

- It was only in the later stages of the cancer programme that the needs of people living with and beyond cancer were better understood. A validated measure of quality of life after cancer is still being piloted.

- Variation in quality of secondary and tertiary cancer services undoubtedly persists. However, rigorous assessment of the quality of individual cancer services is no longer routinely undertaken.

- Improving cancer survival has been identified as a key aim in each cancer strategy. Despite this, there has been a lack of accountability for achieving this at a local level.

- Some of the key metrics needed to monitor progress (eg stage at diagnosis) have only recently become available throughout the country.

- The disruption caused by the reforms introduced in 2012 led to a loss of momentum on improving cancer care, which has still not fully been regained. National leadership and support for cancer networks was significantly downgraded, impacting on progress on cancer.

What needs to happen for cancer services to catch up?

The announcement by the Prime Minister (in early October 2018), of a new cancer strategy to form part of the NHS long term plan is extremely welcome. In particular, the Prime Minister focused on early diagnosis and set an ambition to increase the proportion of patients diagnosed at early stage from one in two to three in four people by 2028. This should help to eliminate the gap in survival rates between England (as well as the rest of the UK) and other comparable countries. The Prime Minister also spoke about reducing the age for starting bowel screening to 50 years, investing in scanners and rapid diagnostic centres.

Achieving this goal will be challenging, especially as the proportion of patients being diagnosed at early stage has remained almost static between 2015 and 2017. We know that patients in the UK are uniquely worried about bothering their GP. GPs in the UK are much less likely to investigate or refer patients than those in comparable countries and hospitals are feeling swamped by current levels of referrals (and are failing to achieve the 62-day standard). Based on the experience of the last 20 or so years of the National Cancer Programme, whole-system change will be needed if the unfinished business of closing the cancer survival gap between England and other countries is to be completed.

Actions

- Bowel screening: The change to Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) testing should lead to increased participation rates but this needs to be accelerated. Endoscopy capacity also needs to be increased considerably. This could be done by increasing the non-medical endoscopy workforce. Current endoscopy capacity could also be released by introducing FIT testing in primary care for patients with low-risk colorectal symptoms. This has recently been shown to be safe and effective in a paper from Denmark, published in the British Journal of Cancer. However, it will require a major shift in primary care practice. Lowering the age of first bowel screening to 50 (as per the Prime Minister’s conference commitment) will improve outcomes, but will require further expansion of capacity.

- Early detection of lung cancer: The recently announced results of the NELSON trial are very encouraging, showing a 26% reduction in lung cancer mortality among men at high risk of lung cancer who underwent serial low-dose CT scans. Importantly, the proportion of patients who were diagnosed with operable (early stage) disease increased to 67%. We need to ensure that the findings from these studies are translated to benefits for patients as soon as possible.

- NICE Guideline implementation: NICE Guideline 12 should be fully implemented. This guideline recommends that GPs should investigate patients who have symptoms which indicate a 3% or higher risk of cancer. However, these guidelines have not yet been fully implemented and efforts are being made to increase GP awareness. Some, but not all, CCGs have changed their referral templates to comply with the guidelines and tools are being developed to assist GPs in assessing levels of risk. Much more work will be needed to change GP practice (and raise public awareness about symptoms of possible cancer).

- Rapid diagnosis centres: The government should be ready to act quickly to spread learning from the Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate (ACE) Programme (run by Cancer Research UK), as evidence emerges of benefit to patients with non-specific symptoms. Although a primary aim would be to diagnose cancer earlier, these centres would also facilitate earlier diagnosis of other significant conditions. These could (and possibly should) be located outside acute hospitals for convenience for patients, and so that diagnostic facilities are not competing with those needed for emergency care pathways.

- 62-day standard: It will be important to continue to measure the timeliness of investigations and treatment within hospitals, though modifications of the 62-day standard should be considered as new pathways evolve.

- Diagnostic workforce and equipment: More patients will undoubtedly need to be investigated. This will require more CT, MRI and endoscopy facilities and an increase in the associated diagnostic workforce. Changes in skill mix need urgent consideration, as does exploring the potential of outsourced reporting (if necessary to other countries) and artificial intelligence (AI).

- Prevention and personalised care: The push for earlier diagnosis should not be at the expense of investment in prevention (which will require reversing cuts to public health budgets as well as cross-government effort on the causes of obesity, smoking and excess alcohol consumption) or further progress in supporting cancer survivors after treatment. Success in early diagnosis will mean more people living after cancer: enabling their wellbeing and health is crucial.

- Funding and accountability: Decisions will be needed on where accountability lies for earlier diagnosis (and thus improved survival) as this will require concerted efforts from public health, primary and secondary care. Integrated care systems might be given responsibility for this, but whichever bodies are funded (whether cancer alliances, sustainability and transformation partnerships or integrated care systems) will need to produce credible plans and have progress transparently monitored.

-

Monitoring: Key metrics will include:

- uptake of screening (especially bowel) and outcomes

- uptake of ‘case finding’ for lung cancer and outcomes

- GP awareness and compliance with NICE Guideline 12

- referrals to diagnostic centres and conversion rates

- stage at diagnosis (by cancer site and age)

- 1- and 5-year survival

- emergency presentations

- 2-week wait, and 62-day standard compliance (or modifications)

- reduction in unwarranted variation of any of the above.

- Progress reports: Public Health England’s National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) should be charged with producing regular (monthly or quarterly) reports on progress, both nationally and locally.

- Attitudinal change: Perhaps the greatest challenge will be making these changes work with the grain of the current NHS gatekeeping model. This will require: giving the public faster and easier access to primary care and/or diagnostic services and encouraging them to present earlier when they have symptoms; encouraging GPs to lower their thresholds for investigating and referring patients; ensuring that commissioners do not block referrals and that hospital clinicians and managers welcome, rather than discourage, referrals (subject to reducing current capacity restraints). All of this will require building support for the changes across the NHS as well as providing the necessary funding. Some of this funding will need to be used for building capability and supporting cancer alliances to work with other local NHS partners to improve services.

Lessons for the future?

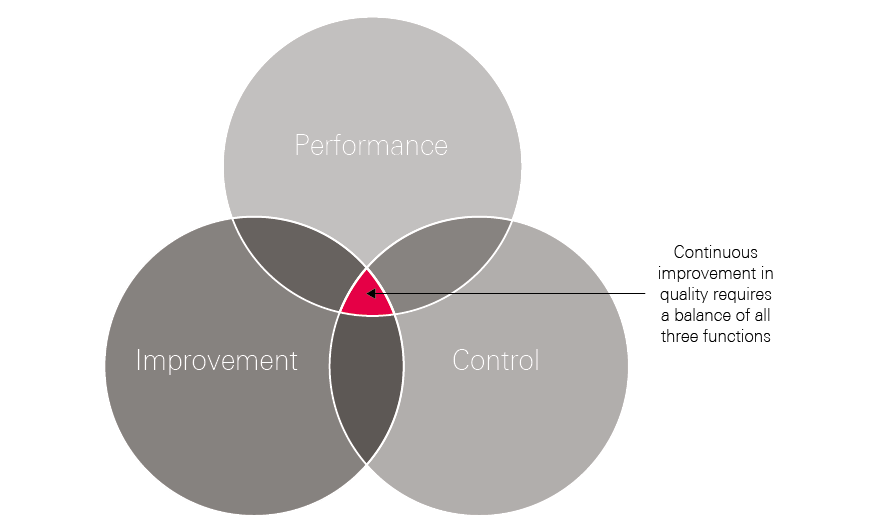

This report describes what was attempted to build support for the earlier phase of the National Cancer Programme. The actions described above would require a similar effort but across broader territory, including primary care. From our analysis of what has gone before, it is possible to identify a set of ingredients that have to fall into place to improve the diagnosis, treatment and care of patients, whether in cancer, or any other condition:

- Belief (at all levels of the system) that there is a problem that needs to be addressed.

- An understanding of what the drivers of that problem are.

- Data to accurately monitor the drivers and the outcomes of interest.

- Interventions to address the problem, with evaluation built in.

- The resources to supply the interventions, for example, workforce or capital investment.

- Support and encouragement for implementation (local capability and national support).

- Accountability for improvement.

Looking back over the past two decades in relation to cancer in England, although national strategies since 1995 have repeatedly described the problem to be solved (poor cancer survival) (1), some of the subsequent ingredients listed have only very recently fallen into place. It took the best part of a decade to develop both belief (1) and an understanding (2) of how important a role late diagnosis was playing in England’s poor cancer outcomes, and insight into the factors that might be inhibiting patients from coming forward, and general practitioners from referring.

It is only in the past few years that data (3) has been collected systematically across the country on stage of cancer at diagnosis for each patient, a metric crucial to monitoring progress in the various interventions being tried, including earlier rapid diagnosis and expanded screening programmes. But, although many of the factors are now in place for accelerating progress in early diagnosis, austerity and the disruption in the wake of the 2012 NHS reorganisation has disrupted other key components, for example, the capability and accountability for making change happen at local level. Although the wheels are now turning again in the form of cancer alliances, integrated care systems and sustainability and transformation partnerships, momentum was lost at national and local level and has had to be rebuilt.

Our report highlights the importance, above all, of the human infrastructure that needs to be in place to wield the soft power that is crucial to engage support and motivate clinicians and managers across a complex service. Many of the ingredients listed require attention to be given to beliefs and behaviours, alongside the evidence and skills to implement change. Without these, the injection of resources will not be effective.

Introduction

On 20 May 1999, in a statement to the House of Commons, Tony Blair, then Prime Minister, announced that he was hosting a high-level seminar on cancer later that day at Number 10 Downing Street. The seminar would bring together experts on cancer, from prevention to screening and treatment, including senior clinicians and researchers from the NHS, leaders from the voluntary sector and a patient representative. The statement went on:

All people, wherever they live, should have access to high-quality cancer services. This was the aim of the Calman–Hine report A policy framework for commissioning cancer services. However, when the Calman–Hine principles were adopted in 1995, no machinery to monitor progress was established. We are now rectifying that omission.

Described by Tony Blair in the Daily Mail as a crusade to ‘save 60,000 lives’, the press release following the meeting announced a number of proposals, including a new National Cancer Action Team, more challenging targets, new guidelines and the first-ever national survey of cancer patient experience. A large amount of machinery was put in place in the months following the seminar, which culminated in The NHS Cancer Plan, published in September 2000.

The NHS Cancer Plan aimed to be the first large-scale, centrally driven effort to improve services and outcomes for a specific disease in the NHS in England. At its zenith, a team of civil servants in the Department of Health was complemented by the outward-facing National Cancer Action Team, comprising NHS managers and clinicians, both led by a full-time National Cancer Director. More than 70 people worked to assemble evidence, commission research, develop and distribute data, support networks of local clinicians and managers, and monitor progress across the NHS.

Three national cancer strategies have followed, the most recent published in 2015. Cancer remains a national priority, one of only two clinical areas singled out in the Five year forward view in 2014, and there are indications that it will be prioritised in the forthcoming 10-year plan. But much of the centralised improvement infrastructure set up after 2000 was either scaled back or broken up and moved into different bodies in the wake of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act. National cancer waiting time targets remain and are still the object of political and media scrutiny, but the continuing effort expended on improving outcomes and quality of care is much less visible.

The ambitions behind the first cancer plan were bold: to raise the level of cancer services to be the ‘best in Europe’, and to build for the future ‘so that the NHS never falls behind in cancer care again.’ These ambitions have fallen short. In 2018, the CONCORD-3 study of international cancer survival published its most recent data, for 2000 to 2014. Although survival rates have improved for almost all cancers, the UK has still not caught up with other European countries – with the exception of breast cancer, where the gap has narrowed.

This report does not attempt to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the NHS Cancer Plan and its subsequent strategies between 2000 and 2015. Instead, drawing on documents, official data and oral evidence from almost 70 people involved in its creation and implementation, the report aims to provide an account of what these national strategies were designed to do and how they worked in practice. A full list of those we interviewed is available as an appendix. We have also analysed data on the progress in treatment and outcomes of cancer services in the same period, and we consider what factors might have contributed to success and failure in how cancer services developed.

Our aim is to draw out learning for the future, not least for the policymakers currently pondering how to invest (and account for) the additional resources that have been promised by the government. There are striking parallels between today and the year 2000: extra resources announced after a period of underfunding, coupled with high expectations on the part of politicians under pressure to demonstrate tangible results to patients and the voting public. In 2000, there was also an urgent sense that improvement hinged on the engagement and mobilisation of the clinical workforce, a workforce described by the NHS Cancer Plan as ‘overworked, run off their feet, and exhausted’.

Background: policies and pledges from 1995–2015

1-1 Calman–Hine: 1995–1997

In his foreword to The NHS Cancer Plan, Secretary of State Alan Milburn hailed it as the ‘first ever comprehensive strategy to tackle the disease’. This was mostly true: the NHS Cancer Plan covered everything, from prevention and screening, through to end of life care. But with respect to the services that diagnosed and treated cancer, the plan built on foundations laid under the previous government. In 1995 the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales, Kenneth Calman and Deirdre Hine, published A policy framework for commissioning cancer services, commonly referred to as the Calman–Hine report. It contained proposals for changes to cancer services that reached deep into the NHS, and particularly into the way doctors and other professionals organised their work.

Driven by the principle that all patients should have access to uniformly high standards of treatment and care, Calman–Hine recommended the creation of cancer units in district general hospitals, with a full range of supportive services coordinated by a lead clinician. More specialised treatment was to be centralised in cancer centres, based in larger hospitals, serving populations of 1 million people or more. The report also recommended that cancer networks be created to link all these services, across hospitals and general practice. Within hospitals, all patients should be managed by MDTs, bringing together surgeons, oncologists, nurses and other professionals, essential to decide on the right course of treatment for each patient. This kind of collaborative approach, according to one of the NHS managers involved in the subsequent NHS Cancer Plan, was rare in the 1990s:

… although it seems almost impossible to think about today, the colorectal surgeon was not talking to the pathologist, even in his own organisation necessarily, and certainly would not automatically have an oncologist involved in cases.

Teresa Moss, former Director, National Cancer Action Team

Calman–Hine was badged as ‘guidance for purchasers and providers of cancer services’. It was pulled together by a small team of clinicians and academics with support from civil servants, but, as one of its authors remembers, it did not have strong backing from ministers, nor did it have much clout from the Department of Health in terms of implementation:

Ken [Calman] wanted to make this initiative (on cancer) but he did not have funding on any scale from the Department of Health or government. They weren’t interested in spending new money at that stage. So the format was advice to commissioners. ‘You’ve been given these pearls of wisdom, please do it without any resource.’

Peter Selby, Professor of Cancer Medicine, University of Leeds

There was, however, some central funding for the development of a series of service guideline documents which followed the report. These summarised what processes of care were most likely to be associated with the best outcomes for individual cancers. They were produced by an expert advisory group, chaired by Professor Bob Haward. The first was on breast cancer (published in July 1996), followed by colorectal cancer (November 1997), lung cancer (June 1998), gynaecological cancers (July 1999) and upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancers (January 2001). These reports became known as ‘Improving Outcomes Guidance’ or ‘IOGs’, a programme initially managed under the auspices of the NHS Executive, but subsequently transferred to the (then) National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Cancer networks were expected to implement the recommendations from each guidance document, which, from 1997, were accompanied by £10m of recurrent funding for each cancer.

1-2 1997: the arrival of New Labour

Cancer was the only condition singled out in Labour’s 1997 manifesto, with a promise to ‘end waiting’ for surgery for patients with breast cancer. But no timescale was specified, nor funds committed to reduce waiting times. Labour’s initial approach to the NHS was to free up savings by abolishing the internal market, and spend the proceeds on front-line care. Eager to evade their reputation as a tax-and-spend party, they committed to staying within the previous Conservative government’s planned spending allocations for the first 2 years of the administration, which meant only small real terms increases for the NHS. Accordingly, there was little decisive action taken to change the shape of NHS services between 1997 and early 1999, except dismantling some (but not all) elements of the internal market. Other developments did occur that were to prove important in relation to cancer. These included the first-ever tobacco control strategy, Smoking Kills, in 1998, which set a target to reduce the prevalence of smoking from 28% to 24% by 2010.

In May 1999, Tony Blair convened the cancer summit at Number 10 Downing Street and subsequently announced a review of cancer services, plus the creation of a National Cancer Action Team ‘to raise the standard of cancer care in all hospitals’. By October 1999, Professor Mike Richards had been named as the first National Cancer Director.

Pressure on the government to take more decisive action on the NHS increased that winter, driven by media pressure, and the results of the EUROCARE-2 study which showed that cancer outcomes in England were lagging behind other countries. Nick Timmins, then correspondent at the Financial Times, remembers the impact:

… you start getting international comparisons appearing, and we’re not doing so well on some things and we’re particularly not doing so well on cancer. The OECD are suddenly saying, ‘It looks like the NHS isn’t getting terribly good results. It’s not spending very much, but maybe it’s not getting very good results either.’ You get that winter of ’99–2000, where the department’s analysis shows they actually did better than the winter before, but the headlines were just awful, just awful.

1-3 The NHS Cancer Plan

In the first days of the new millennium, news emerged that Mavis Skeet, a 74-year-old woman with oesophageal cancer, had had surgery postponed four times because of bed shortages, amid a winter NHS crisis exacerbated by flu. By mid-January, her cancer had become inoperable.

The result of this cumulative pressure was a radical shift in Labour’s position on NHS spending. In January 2000, on a breakfast television show, Tony Blair announced that Labour would bring NHS spending up to the EU average within 5 years. In the budget 3 months later Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that spending on the NHS would rise by 6% on average (double the average growth of the previous 20 years). In return for this increase, the government was determined to reform NHS services in England. The NHS Plan, published in July 2000, promised thousands of new beds, doctors, nurses and hundreds of new hospitals and GP premises. Medical staff would be subject to new contracts, NHS organisations would be accountable for new waiting times targets (a ‘war on waiting’) and expected to deliver care to new national standards. The NHS Plan also contained a promise of a comprehensive national cancer plan and £570m over 3 years for improving cancer services.

The remit of the NHS Cancer Plan, published in September 2000 was broader than Calman–Hine. It set out strategies for prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment and care, and it also had earmarked funding. Unlike Calman–Hine, it contained detailed plans for implementation over the next 5 years, including milestones and deadlines with dates attached. But it built on its predecessor report in important ways, particularly through the use of cancer networks as the main vehicle for improving services, with MDTs, supported by evidence-based guidance, as the driver of improved care for patients.

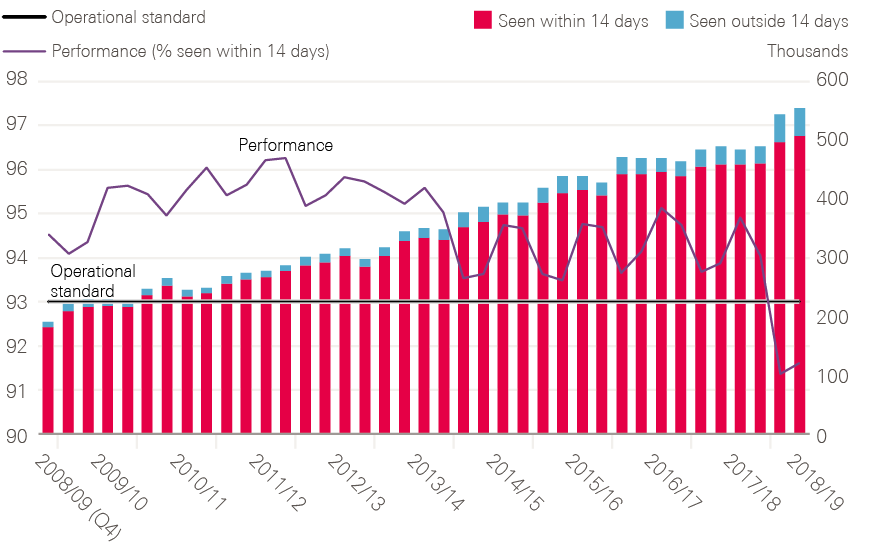

Targets were set for speeding up diagnosis and treatment. By 2005, the NHS was to deliver a maximum 1-month wait from diagnosis to treatment for all cancers, beginning with breast cancer in 2001. Childhood cancers, testicular cancer and acute leukaemia, which were already achieving this standard, were set a more exacting challenge: to begin treatment within 2 months of an urgent GP referral. All cancers would be expected to meet this standard by 2005, with breast cancer leading the way by 2002. The overall goal was to have all patients with cancer beginning their treatment within 1 month of urgent GP referral by 2008.

Money was set aside for new equipment (for example 50 new MRI scanners, and 200 CT scanners), staff (1,000 additional cancer specialists by 2006), and for access to 13 new drugs that the recently created NICE was expected to recommend in 2001. Screening programmes were to be expanded: an extra 400,000 women would receive breast screening, pilots launched for bowel cancer screening and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests made available to all men who wanted them, subject to informed choice. The NHS Cancer Plan also announced the creation of a National Cancer Research Institute, to have an overview of research and plug any gaps. Progress was to be monitored by the newly formed Commission for Health Improvement, and a process of peer review.

Progress in implementing the NHS Cancer Plan was subject to considerable scrutiny. The Department of Health issued its own updates, in 2001, 2003 and 2004. The first survey of cancer patient experience was published in 2002. The National Audit Office (NAO) also produced a suite of reports in 2004 and 2005: Tackling cancer in England, saving more lives (March 2004), Tackling cancer: improving the patient journey (February 2005) and The NHS Cancer Plan: A progress report (March 2005).,,

By 2006, all cancer waiting time standards were being achieved (including 2 months – or 62 days – from urgent referral to first treatment).

1-4 The next stage: The Cancer Reform Strategy 2007–2010

The NAO’s final report in 2005 noted that there were no plans in place to update the NHS Cancer Plan. That soon changed, as the achievement of many of the targets (and the spending of allocated funding) led many in the cancer world to feel that a new strategy would be needed to maintain momentum. Unlike the NHS Cancer Plan, which had been put together by a small group of clinicians led by the National Clinical Director, the new strategy was developed by a much broader coalition of clinicians, researchers and charities.

The resulting Cancer Reform Strategy, published in 2007, acknowledged progress on many fronts, including a larger workforce and shorter waiting times. But it also flagged the gap in survival between the UK and other countries despite all this activity. Once again, a promise was made to catch up:

By 2012 our cancer services can and should become not only among the best in Europe but among the best in the world. This is the aspiration that drives this Cancer Reform Strategy.

Department of Health, Cancer Reform Strategy

There was to be more action on prevention (targets to reduce child obesity as part of a cross-government obesity strategy and public information on the risks of alcohol consumption) and extensions to screening, including more rounds of breast screening and the rollout of bowel screening from 2010. The overall length of targets remained the same, but their scope was broadened. More patients were to be included in the 62-day target from referral to treatment, including those from screening programmes or referred via other consultants. And for women with any breast symptoms, the 2-week wait to be seen by a specialist was to be applied, even if their GP did not suspect cancer. Pledges were also made to improve access to surgery (including training in new forms of surgery), more radiotherapy, and more consistent geographical access to chemotherapy, underpinned by better data.

The Cancer Reform Strategy also contained four major new initiatives on early diagnosis, survivorship, information and equalities. The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative was designed to boost research into the barriers faced by patients, and stimulate innovation in information campaigns. It represented the first concerted effort to tackle late diagnosis of cancer, which was (and still is) believed to be one of the main causes of the UK’s comparatively poor survival rates. The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI) aimed to improve the quality of life for people after cancer treatment, while information and data on cancer were to be improved through the National Cancer Intelligence Network (NCIN). Finally, the persistence of inequalities in access and outcomes was to be tackled by a new National Cancer Equality Initiative.

The actions set out in the Cancer Reform Strategy did not come with any additional funding, and local commissioning bodies were expected to deliver them. Since 2007, much effort had been expended on the development of commissioning skills in PCTs (a programme known as ‘World Class Commissioning’) but, since the late 1990s, the vehicle for local cancer improvement had been the cancer networks (which had reduced in number from 34 to 28). The Cancer Reform Strategy devoted several pages of detail about how cancer networks were to work with PCTs and strategic health authorities (SHAs).

But two events happened in the next two and a half years, which radically altered the structure of the NHS and the environment for all public services. The first was the banking crisis in 2007/08, which led the Labour government to divert public funds to stabilise the financial sector, and tipped the economy into recession. The second was a general election, which brought three terms of Labour government to an end in 2010.

1-5 All change please: 2010 and its aftermath

In the 2010 election campaign, the Conservative party promised to tackle the ballooning public sector debt, and stabilise the economy, which had taken a downturn after the 2008 crisis. Both Labour and the Conservatives pledged to implement flexible sigmoidoscopy for bowel cancer screening, while Labour promised an additional £1bn fund to improve cancer diagnostics. The Conservatives offered a £200m Cancer Drugs Fund, but otherwise reassured the electorate that there would be no ‘top-down’ NHS reform. Comparatively little attention was paid to the elaborate plans developed by the shadow Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, while in opposition. These included sweeping away many of the existing local and regional commissioning bodies, creating GP-led commissioning groups, setting up an arm’s-length body for health and much greater use of the market, to drive an outcomes-focused, self-improving NHS, free of political ‘meddling’.

The 2010 election produced no overall majority. The Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats formed the first peacetime coalition since 1930, and work began on policies to reduce the ‘record public debt’. One early action taken was the creation of a Cancer Drugs Fund, to fulfil a Conservative manifesto commitment. This fund, which began in 2011 and was worth £200m per year, was designed to give patients access to drugs which were not routinely available on the NHS.

Meanwhile, Andrew Lansley, now Secretary of State for Health, pressed on with his reform plans, publishing a white paper in July 2010, which eventually led to the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, after a great deal of opposition.

This backdrop of radical reform at a time of financial austerity was evident in the next cancer strategy that was produced – the first under the new coalition government – in 2011. Improving outcomes: A strategy for cancer, acknowledged the work of those in the previous cancer initiatives, but once again flagged up the stubborn gap between England and comparable countries, this time quantifying it in terms of lives: 10,000 lives could be saved a year if England’s survival rates were as good as the best in Europe., The 2011 strategy was steeped in the language of Lansley’s reform programme: outcomes were paramount, and patients and front-line clinicians were to be empowered, not to be driven via a ‘top-down hierarchy’.

As in 2007, there was no new investment on offer and a hint of how challenging this period would be was contained in the Secretary of State’s foreword to this report. Although, he wrote, the NHS had done comparatively well in the October 2010 Spending Review (the NHS would get small real terms increases, unlike many other government departments). The uplift represented ‘the toughest settlement the NHS has faced for a long time’. Meanwhile, the ambitious pursuit of better outcomes would be the job of PCTs, ‘until they are abolished, and their functions in the relevant area transferred to consortia, local authorities and the NHS Commissioning Board’.

The strategy maintained the focus on national leadership (by retaining the National Cancer Director) and the role of the Implementation Advisory Group to help monitor its delivery. The strategy was not clear about where the National Cancer Action Team would sit under the reformed NHS, and suggested both it and (former) NHS Improvement might become social enterprises. Funding was continued for cancer networks, but the paper hinted that these would also need a ‘new style’ once GP consortia – clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) – were up and running.

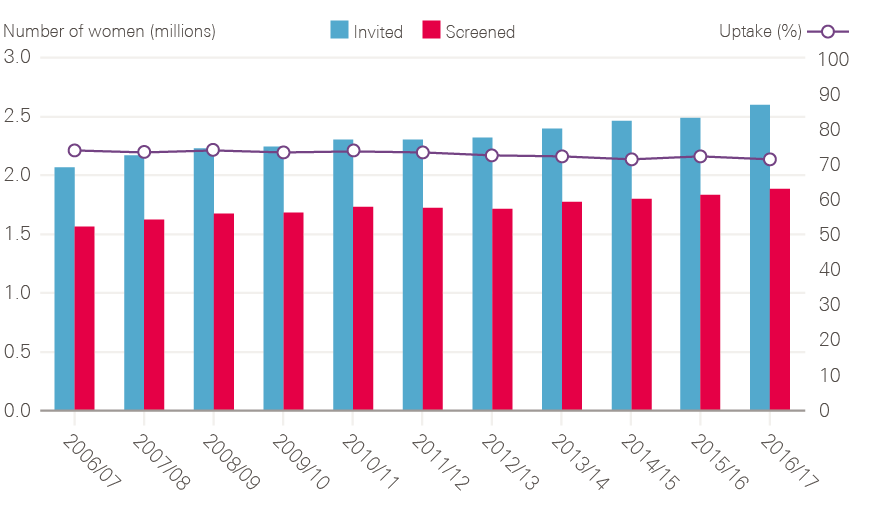

Better data were promised, including new data to be collected on stage of disease. Screening was again extended, including a wider age range for breast cancer (as part of a large clinical trial) and early implementation of flexible sigmoidoscopy for bowel cancer, with full rollout by 2016. Screening was now to be run by the new Public Health England, which would also take the lead on raising patient awareness on early diagnosis.

The strategy listed a range of desired improvements in treatments, including more use of radiotherapy and the most up-to-date surgical techniques. Some of the core principles of Calman–Hine remained in place, for example the continued use of the Improving Outcomes Guidance, MDTs and peer review (albeit the latter subject to being ‘streamlined’). But networks received very limited attention: instead the driver of improved cancer services was to lie with the new GP consortia which, the report noted, were too small individually for optimal commissioning of a complex service such as cancer, and were likely to have to collaborate. It was up to the new consortia in the future to determine whether ‘to continue getting advice and support from networks or to seek such support elsewhere’.

In 2015, the NAO published its appraisal of progress on the 2011 Strategy. It said that survival was improving, but survival rates remained about 10% lower than the European average. There were still persistent variations in access and treatment around the country, and between groups of patients, for example between older and younger patients.

Although staging data had improved in its completeness, the NAO was unhappy that data on cost and efficiency had not improved, and data more generally were not flowing as quickly as it should, hampering commissioning and evaluation. The report noted ‘It is also unclear whether any one organisation, at a national level, has oversight of cancer commissioning across a range of complex treatment pathways’.

The NAO also warned that there was a risk that progress in improving cancer services and cancer information could stall as a result of the 2012 reorganisation, pointing to the downgrading of the National Clinical Director from a full-time to a part-time post, the disbanding, in 2013, of the National Cancer Action Team and the major reduction in funding and staff for the 28 cancer networks.

The mood music at the time was around not having a disease-specific focus, which was seen as a good thing in terms of benefitting cross-disease working etc. I do buy into that rationale to some extent, but essentially it meant that you had a cancer strategy with no real sense of where initiatives in it sat in relation to the wider system, uncertainty over who was really driving it, who was really responsible.

Emma Greenwood, Director of Policy and Public Affairs, Cancer Research UK

1-6 The Five year forward view and beyond

The first substantive vision for the re-engineered English NHS came in the form of the Five year forward view, published in 2014 by NHS England. There was a heavy emphasis on new models of care as a route out of the intense financial and demographic pressures facing the service, but cancer featured, along with mental health, as a priority area.

In the absence of a central cancer team, and a lack of capacity at the Department of Health and NHS England, development of the next (and current) 5-year strategy was handed to an independent cancer task force led by Sir Harpal Kumar, then Chief Executive Officer of Cancer Research UK. The task force published its report Achieving world-class cancer outcomes – A strategy for England 2015–2020 in July 2015. The 96 recommendations were accepted in full. The 2015 strategy called for more progress on prevention, including reducing smoking prevalence to 13% (21% for routine and manual groups) by 2020 and to 5% by 2035. It also recommended a big push towards more rapid diagnosis, aiming for 95% of patients referred by a GP to wait less than 4 weeks for a cancer diagnosis or for cancer to be excluded (and 50% within 2 weeks) by 2020. This would mean a big expansion in diagnostic capacity, and improving the availability of some diagnostic tests to GPs.

Better patient experience would come from all patients having access to test results online, and clinical nurse specialists (CNS) available to all patients to coordinate care. In addition, the quality of life for cancer survivors merited considerable attention, including the development of a quality-of-life measure by 2017. Progress would depend on investment in new infrastructure – replacement and upgrades for all linear accelerators (linacs) and molecular diagnostics, and plugging workforce gaps, especially in diagnostics, oncology and CNS. Finally, the report also recommended creating cancer alliances – a revived form of cancer network – to bring commissioners, providers and patients together, to ‘drive and support improvement’.

These changes were estimated to cost £400m per annum. Once again, a closing of the gap between England and the best of Europe was the prize, with an additional 30,000 patients a year surviving 10 years or more. Progress reports against delivery of the strategy are released yearly by NHS England, while its board also actively monitors elements of the strategy which were priorities in the Five year forward view, namely faster diagnosis and replacing radiotherapy equipment, in addition to existing cancer waiting times targets.

Headline progress

At a national level, there are four key measures for tracking progress on cancer. These are: the number of new cancers being diagnosed (incidence), mortality, survival and patient experience. This section looks at the broad trends in each of these, over an extended time period.

2-1 Incidence

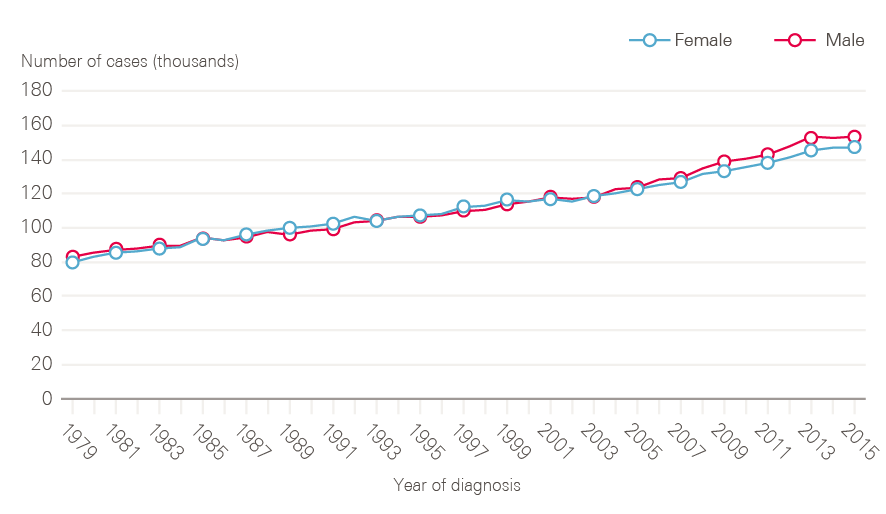

Figure 1: Number of newly diagnosed cancers between 1979 and 2015 by sex, England

Note: All cancers excluding non-melanoma skin cancer.

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

The number of new cases of cancer in England has risen steadily over time (Figure 1). In 2015, there were 299,923 cancers registered (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers), equivalent to 822 new cases of cancer per day. This represents a 40% increase in cancer incidence over 20 years.

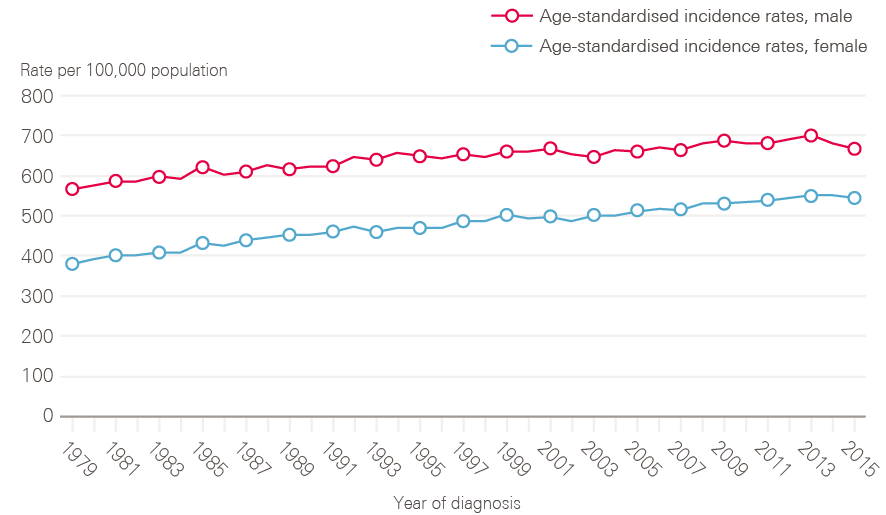

Figure 2 shows age-standardised incidence rates, which take account of demographic change (ie the growing proportion of people surviving longer). These have also risen, by 3% in 20 years in males (648.8/100,000 in 1995 to 667.4/100,000 in 2015), and by 16% in females (from 469.6/100,000 in 1995 to 542.8/100,000 in 2015) indicating that increases in absolute numbers of cases are not simply a product of an ageing population.

Figure 2: European age-standardised cancer incidence rates between 1979 and 2015 by sex, England

Note: All cancers excluding non-melanoma skin cancer.

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

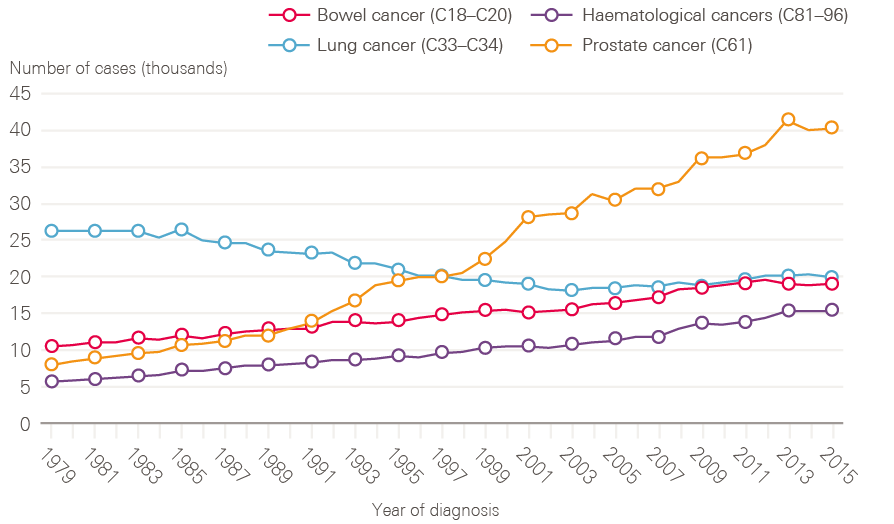

Figure 3: New cases of bowel, lung and prostate and haematological cancers in males between 1979 and 2015, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

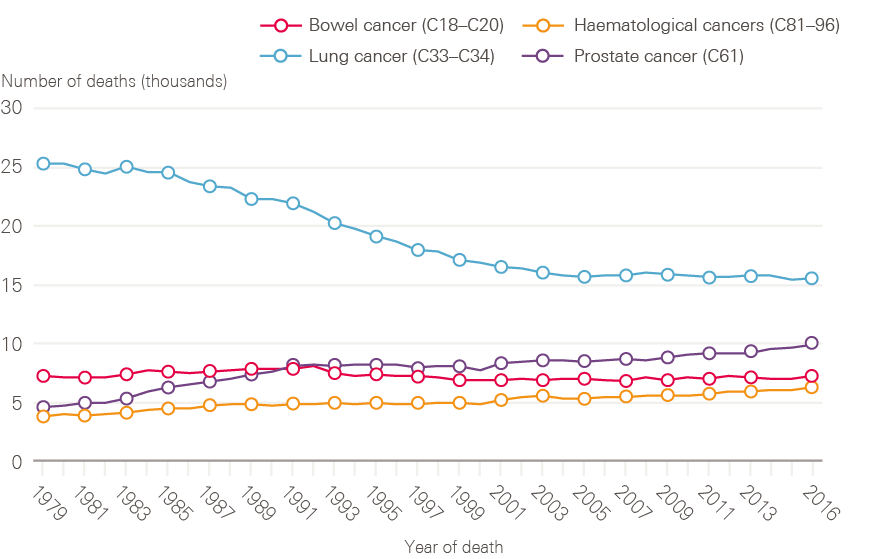

A few cancers dominate, for both sexes. Breast (15.2%), prostate (13.4%), lung (12.7%) and colorectal (11.5%) cancers continue to account for more than half of the cancer registrations in England for all ages combined. For men, while lung cancer cases have fallen in line with decreased smoking rates in earlier decades, cases of prostate cancer have risen rapidly, and now account for one in four (26.1%) male cancer registrations, likely a result of increased PSA testing (Figure 3).

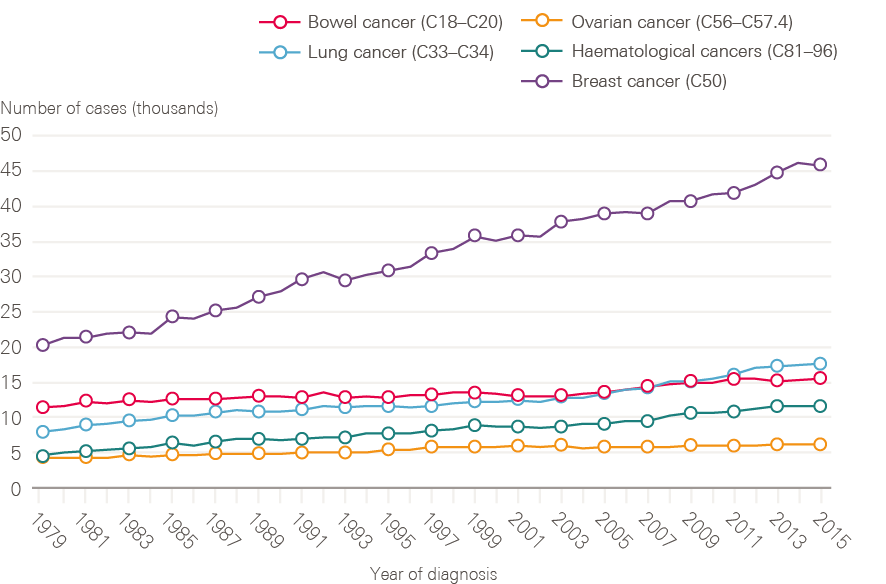

Figure 4: New cases of bowel, lung, breast, ovarian and haematological cancers in females between 1979 and 2015, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

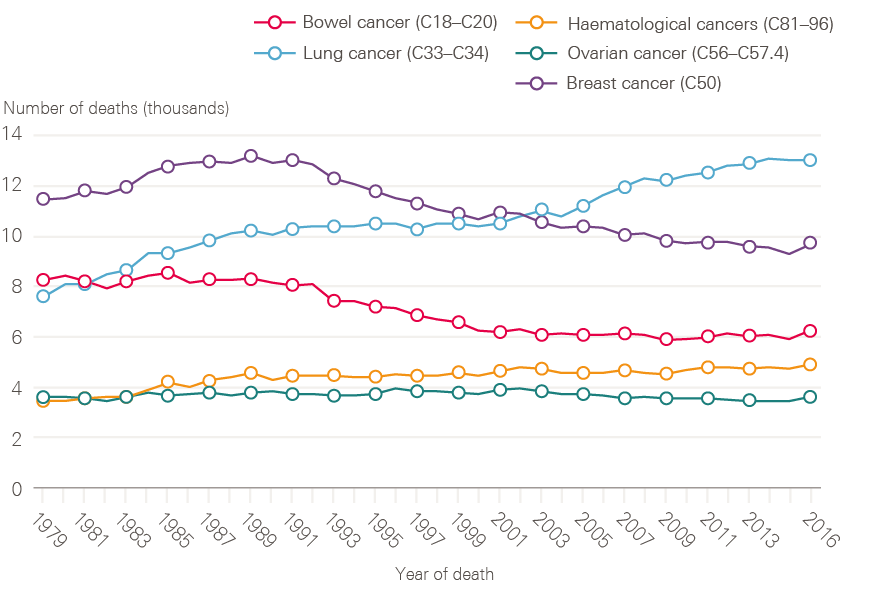

Although smoking rates among men have declined steadily from a post-war peak, for women rates continued to climb until the late 1960s, only reducing significantly from the mid-1970s. This is reflected in lung cancer incidence in women, which has continued to rise (Figure 4). Breast cancer incidence has also continued to rise steadily, and in 2016 breast cancer accounted for nearly one in three (30.8%) of all malignant female cancer registrations.

Rates of cancer incidence vary across the country, from 556.7 per 100,000 people in London to 630.3 per 100,000 people in the North East. There are also inequalities in incidence by demographic groups, with rates of lung and other smoking-related cancers more common in manual workers, and breast and prostate cancer proportionately more common among more affluent groups.

2-2 Mortality

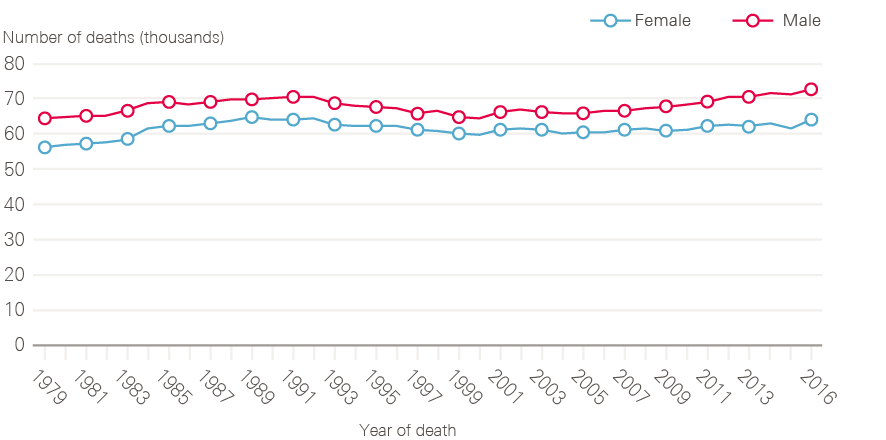

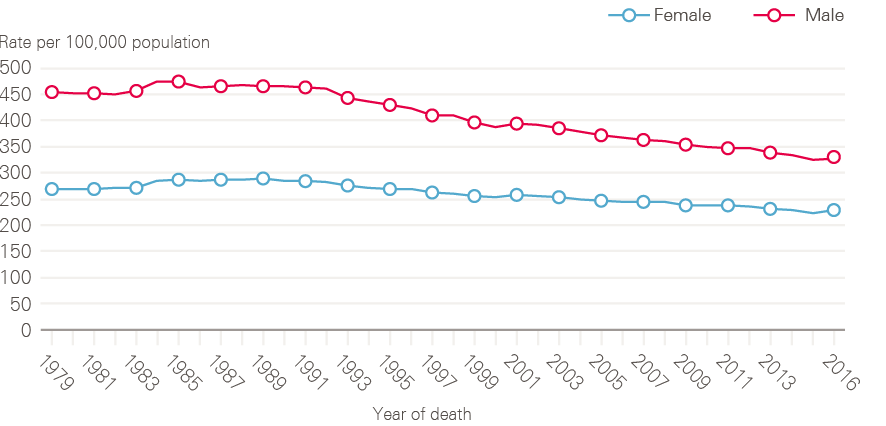

Increasing cancer incidence in England has been balanced by improvements in survival, such that the number of deaths from cancer has remained broadly constant over time (Figure 5). There are around 135,000 deaths from cancer each year in England, with cancer accounting for around 30% of deaths in men and 25% of deaths in women. The steady fall in age-standardised cancer mortality (Figure 6) is in part due to improvements in diagnosis and treatment, but also a reflection of reductions in incidence rates for some cancers with very poor prognosis, especially those linked to smoking.

Figure 5: Number of deaths from all cancers between 1979 and 2016, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

Figure 6: European age-standardised mortality rates for all cancers combined between 1979 and 2016, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

Although lung cancer survival has improved, it remains poor. The reduction in incidence of lung cancer in men is reflected in a decline in death rate through the 1990s (Figure 7). The reverse of this trend is seen for women, in whom both the number of lung cancer cases and death rates continue to increase (Figure 8). This is, at least in part, explained by the fact that smoking rates continued to increase in women long after they had started to decline in men.

Figure 7: Number of male deaths (all ages) broken down by cancer type (bowel, lung, prostate and haematological) between 1979 and 2016, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

Figure 8: Number of female deaths (all ages) broken down by cancer type (bowel, lung, breast, ovarian and haematological) between 1979 and 2016, England

Data provided by Cancer Research UK, July 2017. Source: Office for National Statistics. Available at: cruk.org/cancerstats

2-3 Cancer survival

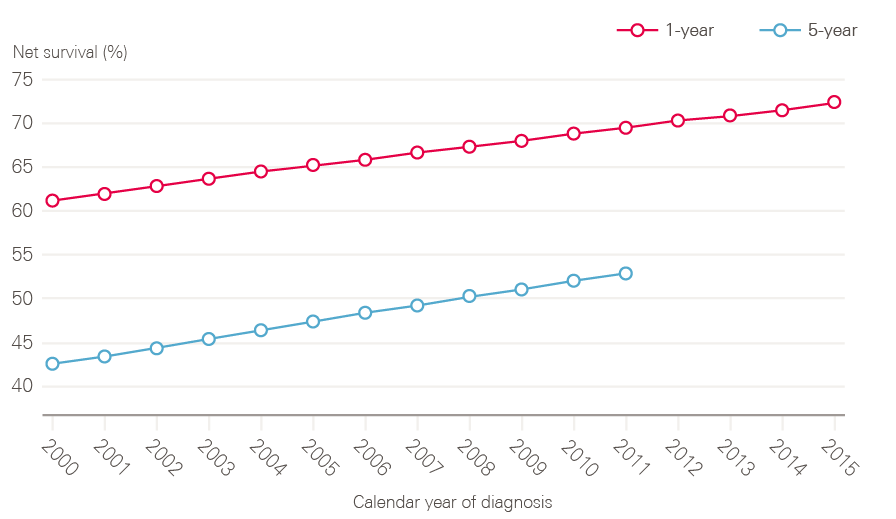

Half of people diagnosed with cancer in England now survive their disease for 10 years or more, and both 1- and 5-year cancer survival (all cancers combined), has been steadily improving in England over the period covered by this report (Figure 9).

Figure 9: 1- and 5-year net survival for all adult cancers (15 to 99 years) between 2000 and 2015 (age, sex and cancer-type standardised), England

Note: Pre-2000 datasets have been excluded because they are not directly comparable due to changes in methodology.

Source: National Cancer Registration and Analytical Service, Public Health England; Office for National Statistics (2017). Available at: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/table01to091yearcancersurvivalbyclinicalcommissioninggroupsinenglandandwithprecisionestimates (accessed on 19 October 2018).

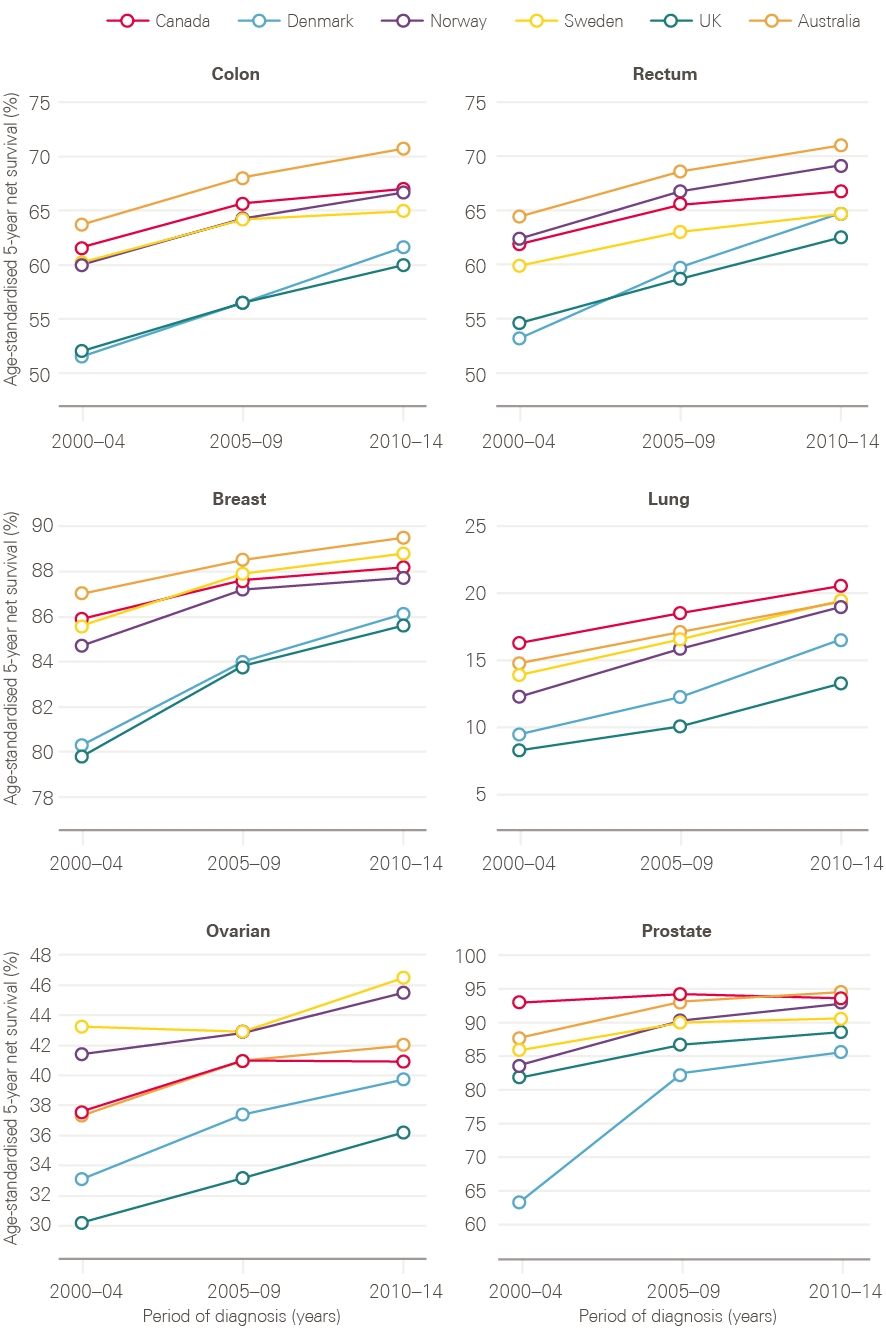

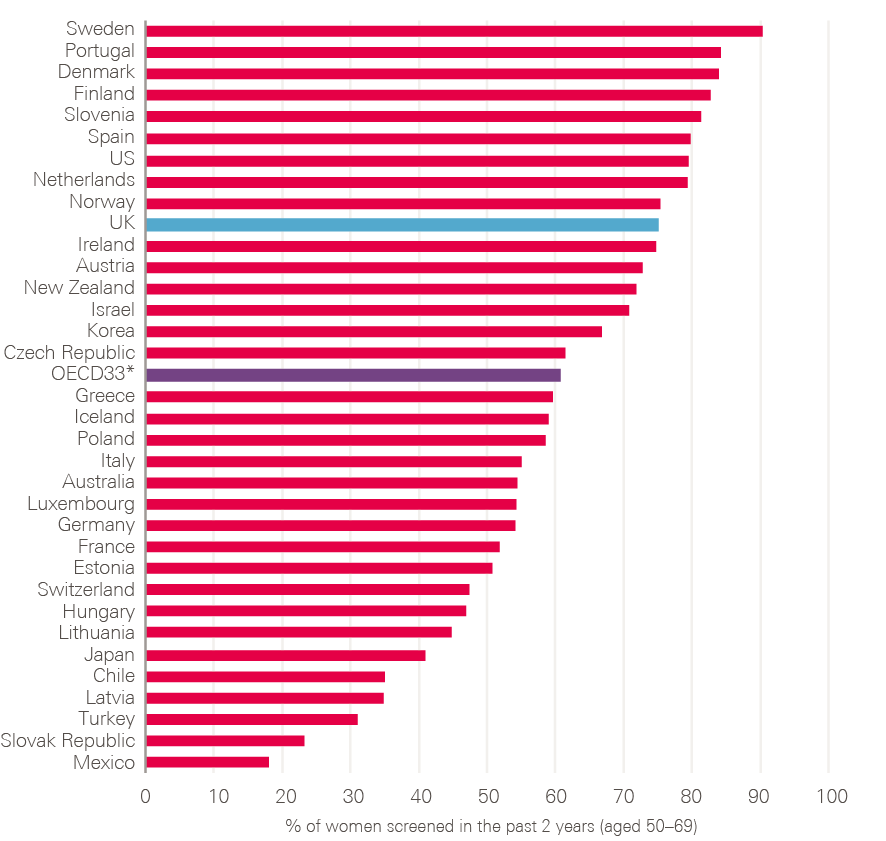

Despite this, survival in the UK continues to lag behind those in comparator countries. The most recent analysis of international variation in cancer survival, the CONCORD-3 study, demonstrates that, while the gap has narrowed for breast cancer, 5-year survival rates for many cancer types continue to be lower in the UK than in comparable countries, with few signs of the gap reducing (Figure 10). There are also significant variations in survival by age and deprivation.

Figure 10: CONCORD-3 survival estimates for the UK in comparison to Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, adults (15–99 years), 2000/04–2010/14

Note: Data provided by Cancer Research UK.

Source: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; CONCORD-3 study. Available at: www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)33326-3/fulltext (accessed on 26 October 2018)

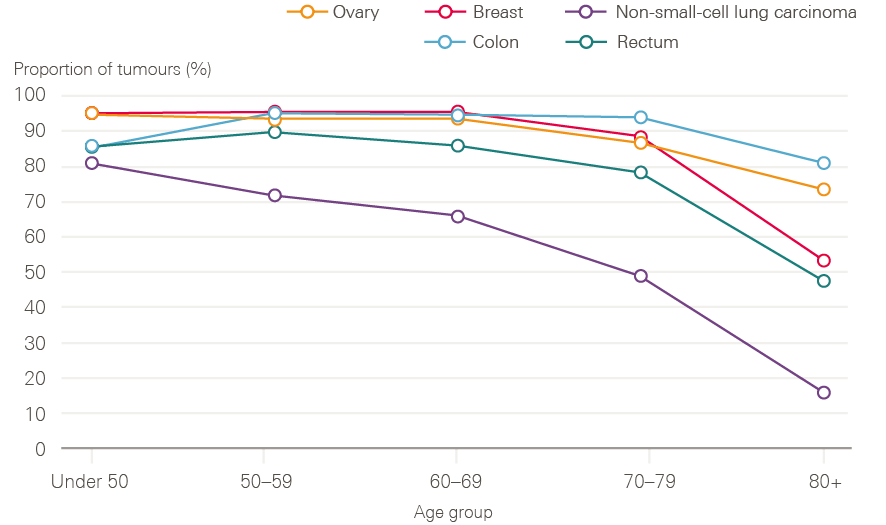

Older adults continue to have poorer survival, likely due to a combination of more advanced stage at diagnosis, and greater frailty, with fewer patients receiving curative treatments. Figure 11 shows data for stage 2 tumours by age group. These tumours are usually operable, but for older age groups, the data suggest that older cancer patients in England are less likely to have surgery for these cancers. It is not possible to know to what extent this is explained by patient choice, co-morbidities making surgery more risky, or a systematic bias in care.

Figure 11: Proportion of stage 2 tumours with a tumour resection recorded by age and cancer type between 2013 and 2015, England

Source: Data provided by Cancer Research UK. Produced by the Cancer Research UK – Public Health England Partnership. Available at: www.ncin.org.uk/cancer_type_and_topic_specific_work/topic_specific_work/main_cancer_treatments

Despite explicit strategies to tackle inequalities and promote equality in access to cancer services in England, including the creation of the National Cancer Equality Initiative in 2008, inequalities in survival by socioeconomic status have persisted throughout the past 20 years. The deprivation gap in 1-year net survival has remained unchanged for almost all cancers, with a clear and persistent pattern of lower survival among more deprived patients.

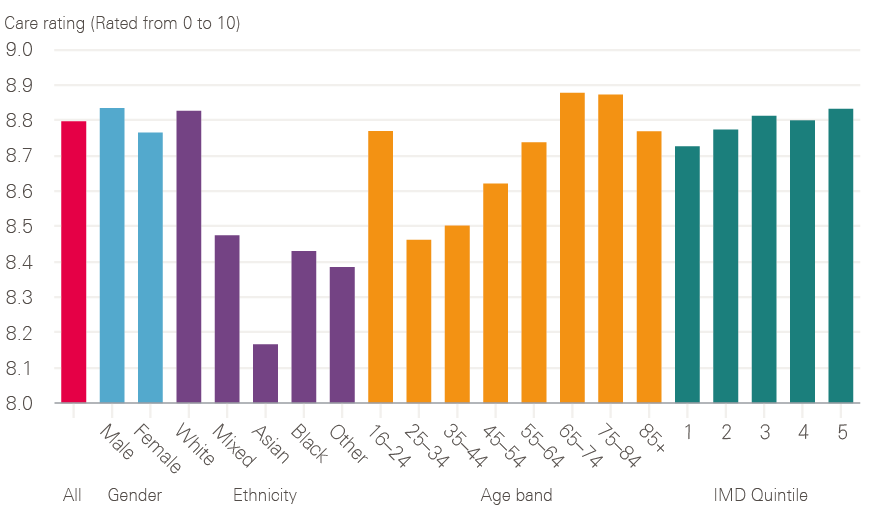

2-4 Patient experience

Cancer patient experience was first measured in 2000 (initially on six tumour groups) and was subsequently repeated, albeit on a smaller sample, in 2004. This showed improved experience in this early period, but is not directly comparable with the annual Cancer Patient Experience Surveys from 2010 onwards. Since 2015, cancer patients have been asked to rate their care on a scale of 0 to 10. Overall care ratings have shown improvements over the last 3 years from 8.70 in 2015 to 8.74 in 2016 and 8.80 in 2017; under the old measurement, the rating also improved between 2012 and 2014. Figure 12 shows that, in comparison with survival rates, there is no significant difference in care experience reported between socioeconomic groups, with an average of 8.73 and 8.83 being reported for Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintiles 1 and 5 respectively (with 1 being the most deprived and 5 being the least deprived). Similarly there is no major difference in care experience reported in relation to gender. Poorer experience is reported by younger adults aged between 25 and 44 and by black and minority ethnic groups, especially Asian patients; older adults aged between 65 and 84 and white patients report a significantly better experience.

Figure 12: 2017 care rating for all cancers broken down by demographics

Source: 2017 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (national results). Available at: www.ncpes.co.uk/reports/2017-reports/national-reports-2 (accessed on 19 October 2018).

Since 2015 care ratings have improved for all tumour groups except brain/central nervous system and sarcoma, both of which had the two lowest care ratings in 2017 (though these tumour groups are of low occurrence compared with other cancers, so the number of respondents is comparatively small). Care ratings for breast, skin and haematological cancers are highest, while brain/central nervous system, sarcoma and upper gastrointestinal cancers perform relatively poorly.

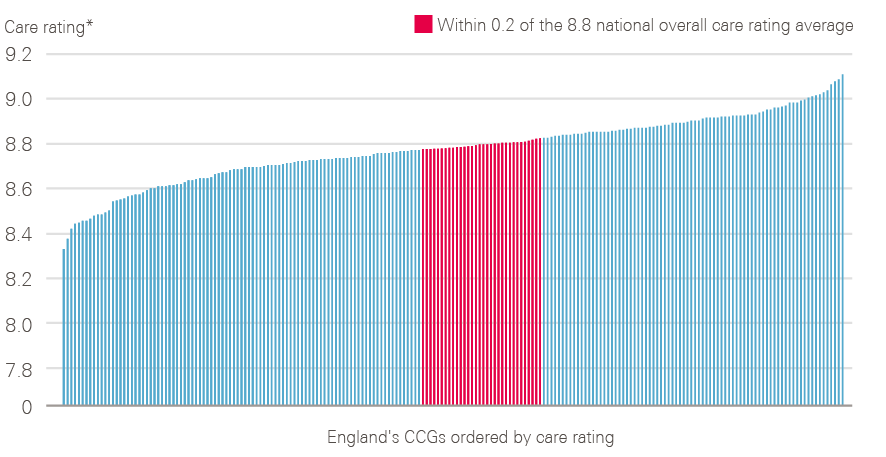

Figure 13: Variation in care rating observed between CCGs in 2017

* Case mix adjusted ratings

Source: 2017 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (local results). Available at: www.ncpes.co.uk/reports/2017-reports/local-reports-2 (accessed on 24 October 2018).

CCG-level data from 2017 show that there is variation in recorded patient experience in England (Figure 13), with an overall care rating difference of 0.78 observed between the best- and worst-rated CCGs (when case adjusted).

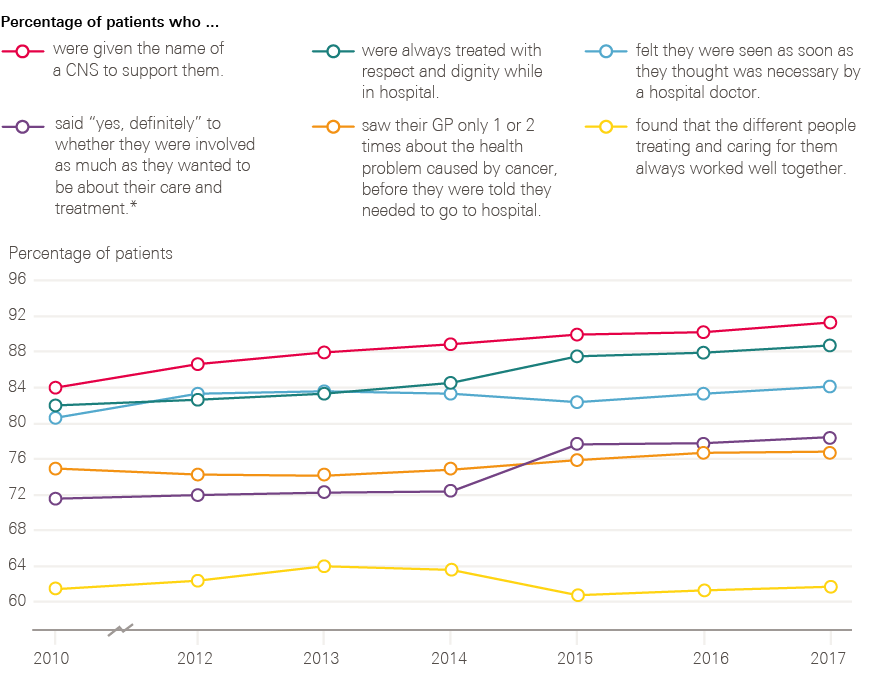

Figure 14 shows the changes over time of a number of key indicators between 2010 and 2017. These results show progress in the percentage of patients who were given the name of a nurse specialist, treated with respect and dignity, and involved in decisions about their care and treatment. There is, however, still room for progress in these measures, with 21% of people still not stating ‘yes, definitely’ to being involved as much as they wanted to be in their care and treatment. There is limited progress reported for patients feeling that they were seen as soon as they thought necessary by a hospital doctor, with 16% still feeling that they waited too long. There is a similar story of limited progress for patients only being seen once or twice by their GP about their cancer symptoms before being referred to a hospital, with 23% of patients still reporting seeing their GP three or more times before referral. There is no long-term progress reported by patients in relation to the different people treating and caring for them always working well together, with 38% not feeling that they always worked well together.

Figure 14: Changes observed for six key patient experience indicators between 2010 and 2017

* In 2010 the patients were only asked about involvement with their treatment, not care.

Source: National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (2010, 2012–2017). Available at: www.quality-health.co.uk/surveys/national-cancer-patient-experience-survey (accessed on 19 October 2018).

Progress across the cancer pathway from 2000

This section describes the main developments since 2000, across the main dimensions described in the various cancer strategies, from prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment, to living with and beyond cancer. One deliberate omission is end of life care, which merits its own analysis. Each section draws on available data, including the testimony of those people directly involved in developing and implementing policy.

3-1 Prevention

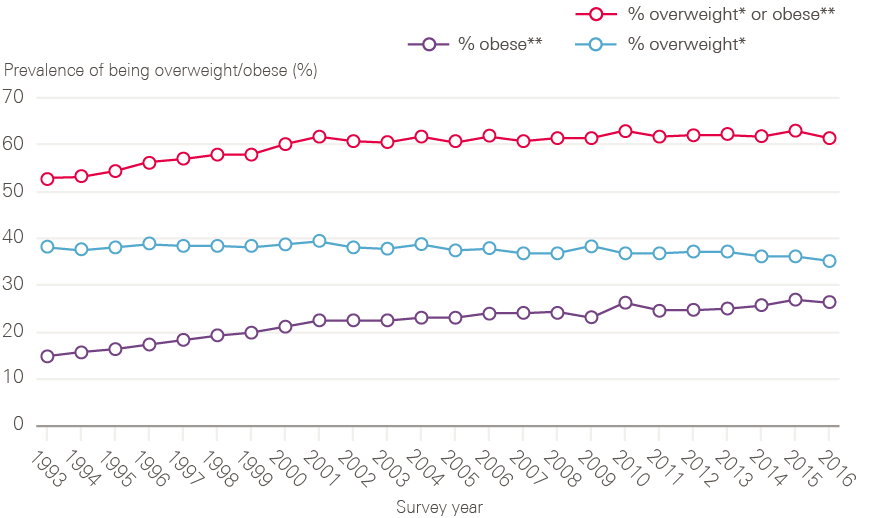

Around 4 out of 10 cancers are caused by exposure to risk factors, such as smoking, that are preventable. The scope of prevention has broadened considerably from the NHS Cancer Plan, which focused heavily on reducing smoking and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, with only brief mentions of the role of alcohol, obesity, lack of exercise and exposure to the sun as cancer risks. The most recent cancer strategy (2015) has been developed on the basis of a much improved evidence base, particularly in relation to the effects of obesity and alcohol consumption on cancer, as well as action to reduce exposure to ultraviolet radiation and boost the coverage of the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination. The next section looks in more detail at the action taken on two of the main risk factors: smoking and being overweight or obese.

3-1-1 Smoking

Action to reduce smoking rates represents one of the most successful strands of health policy in recent years. It is the product of successful mobilisation of a broad set of actors, which included the cancer community, but extended beyond to a coalition of health charities, politicians (able to vote freely) and the research community.

If I look back at my time involved with the cancer community, it [smoking] stands out as the biggest success story, that we’ve changed the nature of the debate, and we have got politicians to do things we never thought they’d do.

Sarah Woolnough, Executive Director of Policy and Information, Cancer Research UK

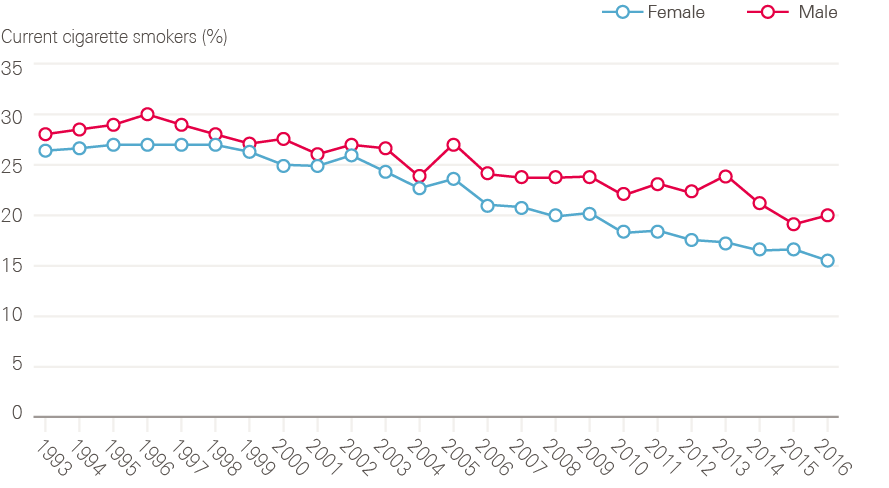

Smoking rates are now at their lowest levels since records began (Figure 15). In 2016, 18% of adults in England smoked cigarettes (20% of men, 16% of women), compared with 28% in 1998 when Smoking kills: a white paper on tobacco was published.

For the UK this represents significant progress. Following the Second World War the UK had a particularly high prevalence of cigarette smoking in men: more than 60% in 1948. In 1950 a seminal paper, Smoking and carcinoma of the lung, was published in the BMJ, linking deaths from lung cancer with smoking tobacco. As further proof of the link emerged, smoking rates in men began to fall, and in 1965 the advertising of tobacco on TV was banned.

Figure 15: Changes in cigarette smoking prevalence in male and female adults (16 and older) between 1993 and 2016

Source: Data provided by Cancer Research UK. Source: Health Survey for England; NHS Digital. Available at: http://healthsurvey.hscic.gov.uk/data-visualisation/data-visualisation//explore-the-trends/smoking.aspx

For almost 40 years after the first evidence of harm from smoking appeared, central government made relatively little effort to regulate tobacco. Taxes on tobacco crept up slowly and, other than the ban on television advertising, the industry was relatively unrestricted. By the mid-1990s, it was clear that the prevalence curves had flattened, and smoking was no longer declining.

In 1997 the Labour Party manifesto included a pledge to ban tobacco advertising, and the first-ever tobacco control strategy, Smoking Kills, was published in December 1998. In the following 10 years, action was taken on smuggled cigarettes, stop smoking programmes, public awareness programmes, smoke-free legislation (2007), a ban on smoking in public places, compulsory health warnings on cigarette packets, standardised packaging and a ban on advertising in shops.

Looking back, for one of the leading civil servants, the period represents a positive feedback loop between evidence and action:

If you look at 2002–2007 there was an acceleration [in tobacco control], as more and more of the properly evidence-based policies happened. There was an acceleration, but I could not at all have guessed that it would end up at the rate of reduction. It’s the smoke-free legislation. Part of that, and the whole denormalisation piece, is about creating a societal movement that it [smoking] is not the right thing, or normal thing, to do and that’s what you hope for.

Nick Adkin, former Head of Tobacco Programme, Department of Health

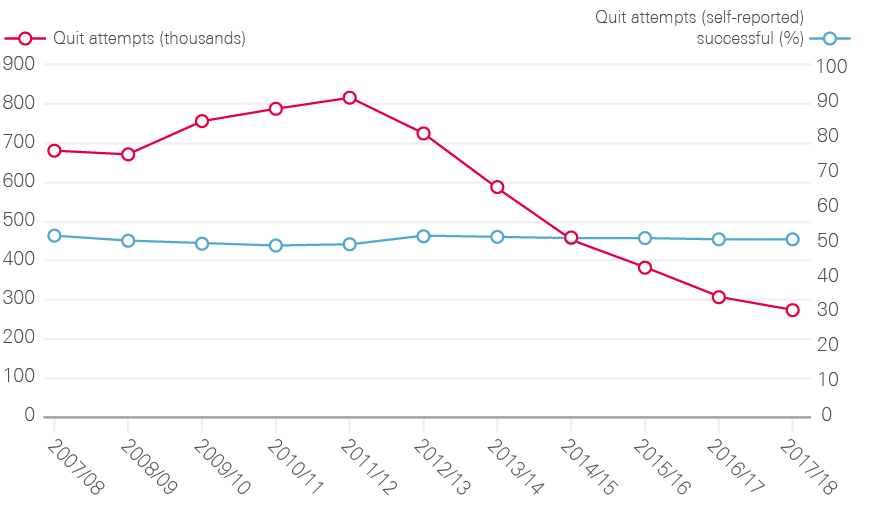

An important part of the NHS Cancer Plan was establishing smoking cessation services in the NHS, reversing the ban on prescribing nicotine replacement therapy, and putting in place financial incentives for GPs to register smokers and refer people to cessation services. According to the latest data, numbers accessing NHS stop-smoking services rose steadily until 2011/12, but have since declined. It is not clear what is driving this. Since 2012, public health has fallen in the remit of local authorities, which have seen their total budgets fall by 32.6% between 2011/12 and 2016/17. While some of the drop-off in smoking cessation numbers may represent under-reporting from local authorities, NHS Digital estimates that access to e-cigarettes has had a role to play. So too might underinvestment in the stop-smoking services previously supported by local government – between 2014/15 and 2018/19 there has been a 32% reduction in real term spend on stop-smoking services.

Figure 16: Number of smoking quit attempts (characterised as setting a quit date) and the percentage of those that were self-reported as being successful between 2007/08 and 2017/18, England

Note: The 2016/17 and 2017/18 data have not been adjusted to estimate for the local authorities that did not provide any data or only provided data for some quarters. These totals are therefore underestimates and not directly comparable with previous years.

Source: Lifestyle statistics; NHS Digital. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-nhs-stop-smoking-services-in-england (accessed on 19 October 2018).

There was also a significant investment in media campaigns from 2003. Charities, including Cancer Research UK and the British Heart Foundation, funded advertisements which produced memorable images such as children breathing in smoke, and cigarettes dripping fat.

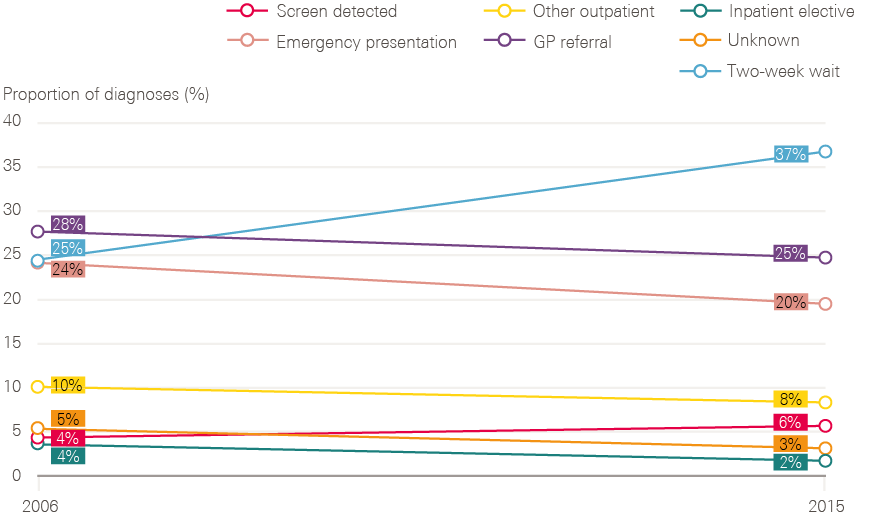

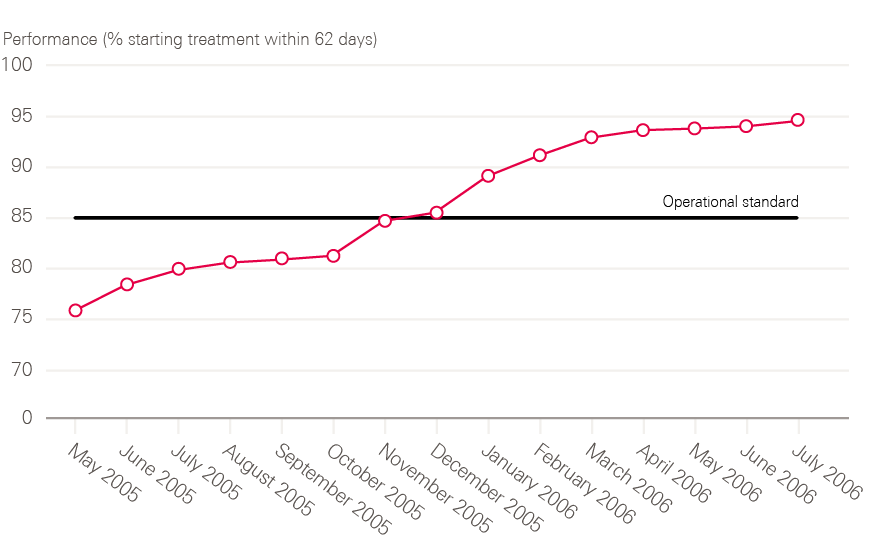

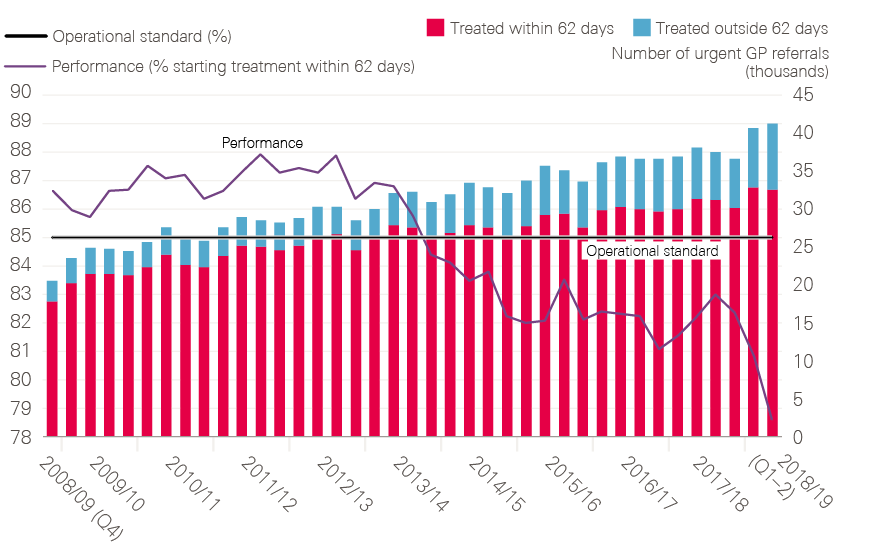

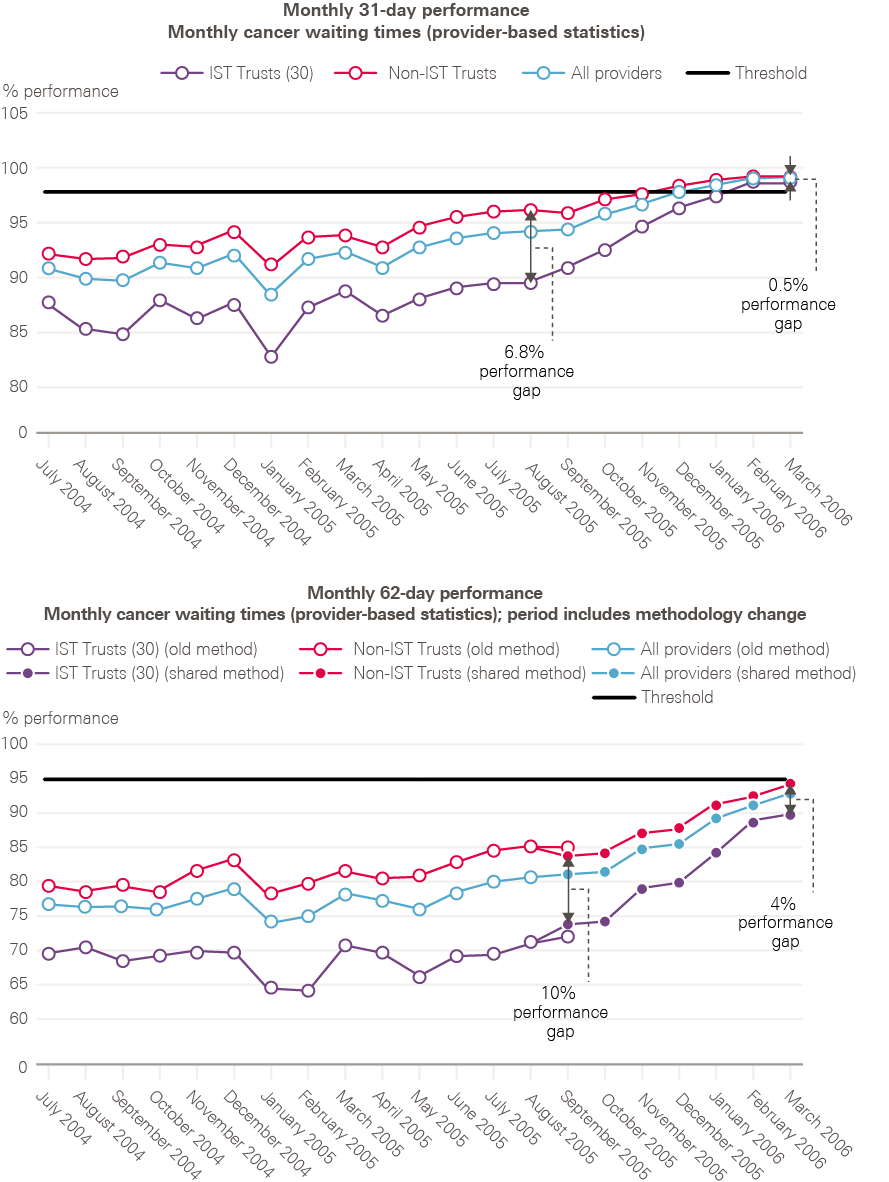

By 2004, the government was being confronted with an important lesson, which was that voluntary agreements with business and industry had only limited traction, in this case to provide smoke-free areas in places of work, which was part of the 1998 Smoking Kills strategy. What seemed to have helped shift this was the impact of the media campaigns on public attitudes, as evidence mounted from Office for National Statistics surveys that the public welcomed smoke-free areas. As Nick Adkin recalls, ‘what we were trying to do is generate the evidence base for ministers to be more comfortable with a decision which was about legislating in this area.’