Introduction

From 1 July 2019, all patients in England should be covered by a primary care network (PCN). PCNs are made up from groups of neighbouring general practices. New funding is being channelled through the networks to employ staff to deliver services to patients across the member practices. PCNs are not new legal bodies, but their formation requires existing providers of general practice to work together and to share funds on a scale not previously seen in UK general practice. The hope of national NHS leaders is that PCNs will improve the range and effectiveness of primary care services and boost the status of general practice within the wider NHS.

PCNs are being introduced at a very difficult time for general practice. The NHS long term plan acknowledges that investment in general practice declined relative to the rest of the NHS between 2004 and 2014, while both demand and complexity of patient needs were rising. This has contributed to a fall in patient satisfaction and increased pressure on staff, which has exacerbated shortages of GPs and practice nurses, who have left the profession at a faster rate than it has been possible to replace them. Despite a target to increase the number of GPs by 5,000 between 2014 and 2020, the number of full-time GPs was 6% lower in 2018 than in 2015.

PCNs will receive funding to employ additional health professionals such as pharmacists and paramedics. Once they are established, The NHS long term plan envisages that the networks will also be a vehicle for improvements in primary care and broader population health, and give primary care more influence within the larger Integrated Care Systems (ICS) – geographically based partnerships of NHS organisations and local authorities – which will be in place across England by 2021.

PCNs are being established rapidly at a time when general practices have limited spare time and energy to invest in creating new networks. Formally announced in The NHS long term plan on 7 January 2019, the vision of what PCNs would be, and what they might be expected to do, was outlined in the 2019/20 GP contract published on 31 January 2019. Details of the funding (how much PCNs will receive and what is expected of them in return) were published on 29 March 2019. Practices had to organise themselves into networks and submit signed network agreements to their clinical commissioning group (CCG) by 15 May 2019. NHS England expects the network contract to provide 100% geographical coverage by 1 July 2019.

Joining a PCN is not compulsory for a GP practice. But by channelling a significant proportion of the increased funding for general practice – £1.8bn of the £2.8bn promised over 5 years in The NHS long term plan – through the network contract rather than directly to individual practices, NHS England has made it challenging for practices to abstain from joining PCNs.

This briefing places PCNs in the context of previous changes to general practice funding and contracting. It examines the rationale for networks, explores relevant evidence and draws out intended benefits and possible risks for the future of PCNs.

What’s happening?

What are PCNs?

PCNs are groupings of local general practices that are a mechanism for sharing staff and collaborating while maintaining the independence of individual practices. NHS England has stipulated that networks should ‘typically’ cover a population of between 30,000 and 50,000 people (the average practice size is just over 8,000). There are likely to be around 1,300 PCNs across England. A single practice with a list size of over 30,000 can register as a PCN, and networks of over 50,000 will be allowed in some circumstances. Networks are expected to be geographically contiguous and co-terminous with local CCG and ICS footprints.

The networks are part of a set of multi-year changes, supported by the new 5-year GP contract published in January 2019. Neighbouring practices enter network contracts in addition to their core GP contract. Groups of practices collaborating as a network will have a designated single bank account through which all network funding – a significant proportion of future practice income – will flow. NHS England has calculated that by 2023/24 a typical network covering 50,000 people will receive up to £1.47m via the network contract.

What will they do?

The new GP contract is designed to deliver commitments made in The NHS long term plan, for example on medicines management, health in care homes, early cancer diagnosis and cardiovascular disease case finding. PCNs are the key vehicle for doing this. Once they are formed, networks will have responsibility for delivering seven national service specifications set out in the contract in return for the new funding (see Table 1).

Table 1: PCN service specifications

|

Service specification |

Introduced from |

Examples |

|

Structured medicines review and optimisation |

2020/21 |

|

|

Enhanced health in care homes |

2020/21 |

|

|

Anticipatory care |

2020/21 |

|

|

Personalised care |

2020/21 |

|

|

Supporting early cancer diagnosis |

2020/21 |

|

|

Cardiovascular disease prevention and diagnosis |

2021/22 |

|

|

Tackling neighbourhood inequalities |

2021/22 |

|

The mechanism being used to channel funds to PCNs is the Directed Enhanced Service (DES). These are voluntary add-ons to the core GP contract, and have been used for several years to incentivise specific services, for example vaccination programmes, or care for people with dementia. The specific DES requirements of PCNs are set out in the Network Contract DES Specification and include the provision of extended hours (ie appointments outside the core contracted hours of 08.00–18.30, Monday–Friday). The focus of the Network Contract DES in 2019/20 is on establishing networks, with five of the seven service requirements coming in from 2020/21. Full details of the seven service requirements are yet to be published, but PCNs will be expected to deliver against an agreed set of ‘standard national processes, metrics and expected quantified benefits for patients.’

How will they do it?

PCNs will be expected to draw on the expertise of staff already employed by their constituent practices, and will receive funding to employ additional staff under an Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS). The work of the networks will be coordinated by a clinical director, a role that will be funded on a sliding scale depending on network size (equivalent to 0.25 of a whole-time equivalent (WTE) GP post per 50,000 patients).

The ARRS is the most significant financial investment within the Network Contract DES and is designed to provide reimbursement for networks to build the workforce required to deliver the national service specifications.

The five reimbursable roles are:

- clinical pharmacists (from 2019)

- social prescribing link workers (from 2019)

- physician associates (from 2020)

- first contact physiotherapists (from 2020)

- first contact community paramedics (from 2021).

The ARRS is intended to cover 70% of the ongoing salary costs of these posts, except for social prescribing link workers, whose costs will be 100% covered. The remainder of the cost of employing these allied health professionals will be met by member practices within the PCN. The sum invested in the ARRS will rise from £110m in 2019/20 to a maximum of £891m in 2023/24. If a network of 50,000 patients should choose to recruit all possible reimbursable roles, it would be eligible for additional ARRS funding of £92,000 in 2019/20, rising to £726,000 by 2023/24 (see Table 2). Suggested job specifications are provided, but PCNs will have flexibility to choose which staff they want and to write job descriptions tailored to local needs.

Table 2: Projected growth in funding for Additional Role Reimbursement Scheme, 2019–2024

|

2019/20 (from July) |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

2023/24 |

|

|

National total |

£110m |

£257m |

£415m |

£634m |

£891m |

|

Average maximum per typical network covering 50,000 people |

£92,000 |

£213,000 |

£342,000 |

£519,000 |

£726,000 |

Source: NHS England and BMA. Investment and evolution: A five-year framework for GP contract reform to implement The NHS long term plan. 2019, p.11.

How are PCNs funded?

£1.8bn of the promised £2.8bn over 5 years of additional funding for general practice will flow through the Network Contract (see Table 3).

Table 3: Revenue streams for PCNs

|

Payment |

From |

Amount |

Notes |

|

Clinical director |

CCGs to PCNs via Primary Medical Care allocations. |

£0.514 per registered patient for the period 1 July 2019 to 31 March 2020. |

Calculated on the basis of 0.25 WTE per 50,000 patients, at national average GP salary (including on-costs). This will be provided on a sliding scale based on network size. |

|

Core PCN funding |

CCGs to PCNs, from core CCG allocation. |

£1.50 per registered patient. |

|

|

Extended hours access appointments |

CCGs to PCNs via Primary Medical Care allocations. |

£1.45 per registered patient. |

Pro rata over 12 months (equates to £1.099 per patient from July 2019 to March 2020). |

|

Network participation payment |

NHS England to individual practices. |

£1.761 per weighted patient per year. |

|

|

Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme |

CCGs to PCNs via Primary Medical Care allocations. |

PCNs will be entitled to claim a percentage reimbursement of either 70% (or 100% for social prescribing link workers) as set out in the Network Contract DES, and subject to a maximum amount. |

The roles for which payment will be made are clearly set out in the Network Contract DES, and payment will only be made once staff have been recruited. |

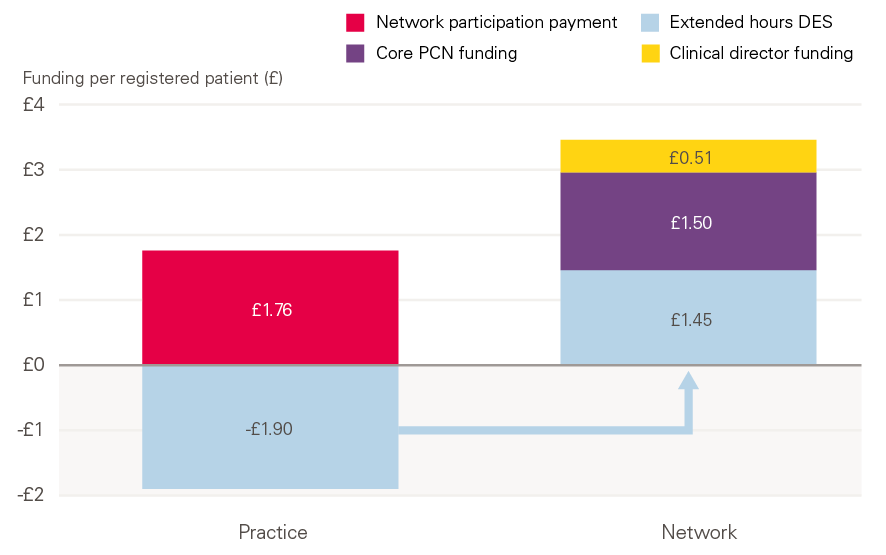

Some of the funding (known as the network participation payment) will be received directly by practices, with the remainder of additional funding directed to the network. In addition, some funding previously received by individual practices (for provision of extended access) will now be allocated to networks instead (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Funding for practices and networks, excluding new roles reimbursement

Note: Extended hours payments previously received directly by practices will now be paid to PCNs. A variable ARRS sum (not shown in Figure 1) will be added to the network payment, depending on the number of staff employed.

Why this, why now?

Although the plans for nationwide implementation of PCNs seem to have emerged very recently, they build on recent policy to encourage general practices to work at greater scale.

The 2014 Five year forward view for the NHS in England set out a vision for greater collaboration between general practices, as well as collaboration between general practices and wider community health services, hospitals and social care. GPs could opt to become involved in developing several new care models, including multispecialty community providers (MCPs) – networks of GPs that would integrate services with other health and care professionals in the community – and primary and acute care systems (PACS), which involved closer integration between primary care and hospital services for a local population.

The 2016 General practice forward view continued in a similar vein, promising the introduction of a voluntary MCP contract to integrate general practice services with wider health care services, encouraging GPs to work at scale across practices to collectively provide extended access, and promising additional allied health professionals in extended practice roles within primary care. In 2017, Next steps on the five year forward view announced an intention to ‘encourage’ practices to work together in hubs or networks of between 30,000 and 50,000 patients. The benefits of larger-scale models of general practice were described as allowing the employment and sharing of a greater range of staff (such as community nurses and pharmacists) without closing practices or forcing co-location of services.

Prior to The NHS long term plan, the approach had been to emphasise the voluntary nature of any collaboration and offer a variety of different forms through which collaboration might happen. Two elements differentiate PCNs from most pre-existing collaborations in general practice:

- Practices working in formal collaboration with each other under a shared network agreement.

- A shared income stream across practices forming a primary care network.

In most localities this represents a sizeable change to the way that general practice is run and funded. By formalising PCNs, the 2019 GP contract goes further than any previous effort in giving clarity and direction on both form and function of general practice at scale in England. In particular, it is intended that new kinds of staff, including pharmacists, physiotherapists and paramedics, will become ‘an integral part of the core general practice model throughout England,’ rather than optional add-ons who could be ‘redeployed at the discretion of other organisations’.

According to NHS England, the networks will ‘enable greater provision of proactive, personalised, coordinated and more integrated health and social care’.

Three key rationales put forward for PCNs in both The NHS long term plan and the 2019 GP contract (the latter in conjunction with the British Medical Association (BMA)) are set out below.

1. A pragmatic response to chronic workforce challenges

The GP contract acknowledges that, despite the commitment to increase GP numbers by 5,000, progress in recruiting new doctors has been ‘more than offset’ by GPs leaving the profession or going part-time. Progress in increasing the number of practice nurses has also been slow and, as a result, many practices had been recruiting to other roles – such as pharmacists – in the wider primary care team faster than had been expected. Hence the decision to give a ‘major boost’ to recruitment of these roles through the PCN route. The choice of target roles is also pragmatic: NHS England and the BMA estimate that (in contrast to GPs) there is, or soon will be, adequate supply of these roles – pharmacists and link workers immediately, physiotherapists and physician associates by 2020 and paramedics by 2021, to avoid ‘net transfer from the ambulance service’.

It is hoped that these wider roles will take some of the pressure off GPs and practice nurses, indirectly helping to ease workforce pressures. Policies already underway to increase the numbers of GPs and practice nurses will continue.

2. Consolidating general practice in the wider health system

PCNs are policymakers’ new answer to an important gap in the local organisation of the NHS. Better integration of primary care with secondary and community services has long been a policy goal, but has been held back by several challenges, including how to actively involve general practice – a key provider of services but generally in small units – in wider decisions about how services are organised and delivered across geographical areas.

PCNs are intended to be more than a vehicle for employing additional shared staff between practices. The NHS long term plan sets out a vision of care delivered at ‘system, place and neighbourhood level’, with PCNs representing a new unit of ‘neighbourhood’ level general practice within the larger units of ICSs. The new clinical directors are expected to provide leadership for PCNs and represent their constituent practices, acting as a conduit between general practice and the ICS. The GP contract makes clear that PCNs and their clinical directors will have access to better data, including predictive risk data, from the network practices and ‘robust activity and waiting time data’ at both individual practice and PCN level by 2021.

Providers of community services are also being asked to configure their services to match network boundaries by July 2019, although there is no detail yet about how this will be implemented.

3. Improving population health

The NHS long term plan sets out an ambition for all NHS organisations to have more of a proactive focus on improving ‘population health’. The term ‘population health’ is used in various ways in The NHS long term plan, but includes action to find and offer services to people at risk of deteriorating ill-health, as well as prevention of illness. NHS England believes that the 30,000–50,000 population size of PCNs breaks population groups in to more manageable chunks for the delivery of interventions to improve population health (single practices being generally too small and CCGs too large). What these interventions look like in practice isn’t currently clear, although it is clear that PCNs will be expected to play a role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and tackling neighbourhood inequalities, as both of these have been singled out as future PCN service specifications.

From 2020, there will also be an Investment and Impact Fund – a savings scheme tied to the development of community-based services that enable reductions in hospital activity – available to networks via their ICS. Guidance has not yet been developed, but the GP contract notes that any monies earned from the Fund are ‘intended to increase investment for workforce and services, not boost pay’.

PCNs in their historical context – what’s the evidence for where we’re going?

There is no directly comparable precursor to PCNs from which to draw evidence, but there has been some evaluation of different forms of networks and collaborations in general practice in the NHS. This section places PCNs in their historical context, considering the evidence related to general practices working at greater scale as both commissioners and providers of services.

Previous forms of general practice at scale

Commissioning

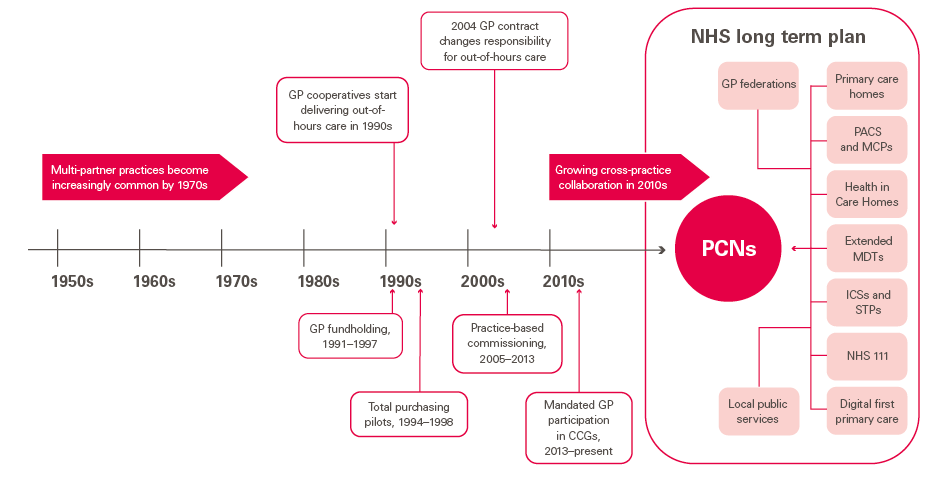

General practice has evolved over time (see Figure 2). From a 1950s model of predominantly single-handed practice, the 1960s and 1970s saw multiple-partner practices become the norm, with falling patient list sizes per GP and improved facilities.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, there were opportunities for GP practices both to have greater control over budgets and to collaborate to do so. From 1991, GP fundholding allowed GPs to hold budgets with which to purchase primarily non-urgent elective and community care for patients. GPs had the right to keep any savings, with policymakers hoping that this would financially incentivise GPs to manage costs while applying competitive pressure to acute providers. By 1997/98, 57% of GPs had opted to become fundholders. From 1994, the ‘total purchasing pilot scheme’ enabled GP practices – either individually or in groups – to commission all services for their patients (although in reality few chose to do so).

Though fundholding was phased out in 1997, from 2005 to 2013 practice-based commissioning (PBC) gave participating practices control over their budgets to purchase secondary care. Practices were given indicative budgets, based on their historic spending, and although they weren’t allowed to directly pocket the savings (the key distinction between PBC and fundholding), a proportion of any savings could be recycled into improving patient care. Though both fundholding and PBC were voluntary, the involvement of GPs in CCGs (replacements for primary care trusts created through the Health and Social Care Act) is not. All general practices are required to be members of their local CCG, but only a minority of GPs have a formal role with the CCG.

Figure 2: Trends in the commissioning and provision of general practice in England

Providing services

In the 1990s, practices started working collaboratively to provide out-of-hours care through GP cooperatives – a trend largely reversed when the 2004 GP contract removed the obligation for GPs to provide 24-hour care for their registered patients.

More recently, there has been a trend towards collaboration between GP practices, pushed in part by reductions in practice funding, rising patient and administrative demands, and workforce shortages, and pulled by new funding opportunities for large-scale GP providers (for example from the Five year forward view).

In 2016, the Nuffield Trust estimated that almost three-quarters of practices were working in collaboration with other practices, and by 2017 this had risen to 81%., The survey reported practices often belonging to multiple collaborations, operating at different levels in the system and for different purposes. A relatively small proportion of practices were working in nationally funded collaborative models (eg as MCP ‘vanguards’ supported through NHS England’s ‘new care models’ programme) and only half of practices reporting collaboration felt that it had been formalised in any way. Existing forms of collaboration in general practice (for providing services) have varied widely in both form and function.

NHS England state that as of 30 November 2018, 93.4% of practices across England considered themselves to be part of a ‘network’, but it is likely that the majority of these networks are not working at the level of collaboration required of PCNs. A more recent study (in press) suggests that previous estimates of levels of at-scale working have been much too high, the actual proportion of practices working together in some form (defined as collaborations that serve more than 30,000 patients) is closer to 55%. The same study estimates the proportion of general practices working closely together at scale to be less than 5%.

How are PCNs different from previous forms of general practice at scale?

- Homogeneity of form: All practices signing up to PCNs are signing the same network agreement and agreeing to the same contractual terms. While there will be variation in how PCNs choose to operate, how they employ staff and how they deliver services, there will be a common basic operating and funding model for all practices in PCNs across England.

- Homogeneity of function: In signing the PCN network agreement, practices will be agreeing to deliver the seven service specifications to be set out by NHS England. Networks are expected to have flexibility to tailor the services they offer to the needs of their neighbourhood, but core contractual obligations will be the same nationwide.

- Requirements on size and location: Although the PCN DES allows for a degree of flexibility around PCN size and geographical footprint, existing forms of general practice at scale (such as super-partnerships, primary care homes and existing networks) vary by size and are not all grouped into neighbourhoods. The advent of PCNs is likely to challenge and potentially disrupt some of these existing forms of collaboration in general practice. GP federations will not usually be allowed to hold the Network Contract DES, and although PCNs may choose to subcontract services to their local federation, the extent to which they do so is likely to vary.

What can the evidence on general practice at scale tell us about PCNs?

Recent examples of scaled-up general practice and networked provision of services provide no clear evidence of impact on quality of care, patient experience or cost-effectiveness. Two studies of networked general practice in one region reported improvement in clinical outcomes and perceived benefits from the perspective of clinicians, but the region in question has had a long track record of using quality improvement approaches to raise standards in primary care.,

Pettigrew et al’s 2018 systematic review searched for evidence of the impact of GP collaborations to explore whether scaled-up general practice can deliver better quality services while generating economies of scale. Their conclusion – that there isn’t enough evidence to confidently conclude that the expectations placed on GP collaborations will be met – was accompanied by a warning that further evidence, together with learning from evaluations of current approaches, is needed before large-scale general practice is pursued as national policy. The review is part of a larger report including case reviews of eight at-scale GP providers. Analysis of 15 quality indicators across these providers was unable to detect marked differences in quality of care compared to the national average, and reported mixed views from patients, some of whom valued new forms of access, while others were concerned about the potential loss of a trusted relationship with their own GP.

NHS England have pointed to primary care homes as a successful precursor to PCNs. Launched in October 2015, there are now over 225 primary care homes in England, at various stages of development, serving 10 million patients. The primary care home model brings together general practices with a range of health and social care professionals to deliver care to populations of 30,000–50,000. There are obvious similarities to the new PCN model on network size, a service delivery model based on a multidisciplinary workforce, and an ambition to combine personalised care with improving population health. Evaluation of primary care homes is ongoing, but an early review by the Nuffield Trust found that participation had strengthened inter-professional working and stimulated formation of new services tailored to the needs of different patient groups. There had, however, been a cash injection of £40,000 from NHS England for each of the primary care homes they evaluated, and the report concluded that developing primary care homes requires significant investment of money, time and support.

Without a substantial body of evidence from existing GP-at-scale organisations to guide policymakers, Mays et al sought to understand the lessons that might be learned for large-scale general practice from other inter-organisational health care collaborations. Their findings are relevant to PCNs in three core domains:

- network size

- leadership

- continuity of care.

Network size

No consistent relationship has been found in primary care between the size of health care organisations and their performance. Mays et al identified trade-offs between being small enough to have flexible and inclusive decision-making processes, and large enough to influence the local health economy. This is of direct relevance to PCNs, which are intended, at least in part, to bridge a gap between individual general practices and emergent ICSs.

Leadership

The time and resources required for health service reorganisations are often underestimated. Strong leadership is often cited as essential in overcoming these challenges, but the primary care workforce has historically been relatively unengaged in leadership training and development.,

Continuity of care

Evidence suggests that continuity of care in general practice is associated with higher quality care for particular patient groups.,, Offering extended hours access will be a core requirement of PCNs, but this responsibility will be shared across practices in a network and between different allied health professionals. PCNs can meet their contractual obligations by offering extended hours appointments with nurses, physiotherapists and other multidisciplinary team members. Any evaluation strategy for the networks should include monitoring the effect of PCNs on continuity of care.

How does evidence on GP contracting and commissioning relate to PCNs?

Some studies of previous approaches to GP commissioning have indicated that linking clinical decisions with financial responsibility can deliver improvements in performance, but these have tended to be more modest than had been anticipated. A 1998 evidence review from The King’s Fund found that GP fundholding was associated with increased transaction costs and created a two-tier system in access to care for patients of fundholders and non-fundholders.

Health Foundation analysis from 2004 of commissioning changes made in the 1990s did not find any substantive evidence to demonstrate that any approach had made a significant or strategic impact on secondary care services. Neither GP fundholding nor practice-based commissioning showed any significant improvement in outcomes.,

What can be learned from attempts to scale general practice in other health systems?

Experiences over the past two decades of attempts to deliver networked general practice in New Zealand, Australia and Canada highlight trade-offs between voluntary and mandatory participation. Where joining a network was incentivised but not mandatory, a sizeable minority do not participate, but mandating collaboration is shown to risk clinician disengagement and even resistance. In Scotland, the new GP contract mandated that practices became part of a geographic quality cluster, but early evaluations are mixed and clusters seem to be struggling in areas where practices face different issues and struggle to agree priorities. In Wales, 64 clusters of practices covering between 30,000 and 50,000 patients were set up from 2014 to improve the planning and delivery of local services. An inquiry published in 2017 found that, while there were some impressive examples of collaboration, clusters as a whole were still immature, needed more support with their development, and were finding that financial and demand pressures on primary care were hindering progress in some areas.

Evidence base for the interventions to be used by PCNs

Many of the intended benefits of PCNs hinge on the capacity of the additional staff to free up GPs, using the multidisciplinary team to deliver a range of more effective and personalised services to patients. The BMA’s PCN handbook offers some evidence of the probable benefits relating to the new roles. We have not reviewed the evidence on the individual roles and interventions that the PCNs are likely to deliver, but the evidence for the impact of some of these roles is not always clear – for example, for social prescribing link workers (and for social prescribing interventions more broadly).,

The National Association of Link Workers (NALW) highlights that there is currently no research exploring the knowledge, skills, experience and support needs of existing link workers. Ultimately, the success of social prescribing is contingent on the availability of services within communities to effectively address identified needs. Of the link workers who responded to a small NALW survey in 2019, 74% identified ‘a lack of resources and/or funding in the community and difficulty in accessing resources in the community/council’ as the most challenging aspect of their role.

Risks and challenges

PCNs are a core part of The NHS long term plan’s vision of achieving more proactive, coordinated care through greater collaboration between GPs and other services in the community. Drawing on the skills of a wider range of health professionals is a pragmatic response to rising demand and shortages in the GP workforce. PCNs have the potential to improve coordination of services for patients and to support GPs to deliver high-quality care. They may also support GP involvement in wider NHS decision-making.

The decision to direct much-needed additional funding and resource through PCNs rather than direct to practices is a clear signal that policymakers see scaled-up general practice as the best route to a more secure footing for general practice and better care for patients.

But PCNs are not without risks. This section analyses potential barriers and risks to the successful roll-out of PCNs, and what they might mean for general practice.

Speed of implementation

The most immediate challenge is the extremely tight timetable for setting up the networks. Practices across the country have had to understand the policy, form themselves in to networks, appoint clinical directors and agree ways of working sufficient to sign their network agreements, all in very little time.

In their design of the network policy, NHS England and the BMA have attempted to strike a balance between top-down guidance and allowing room for practices to determine what organisational forms are best suited to them. Provided there is a single ‘nominated payee’ for funding, practices can choose their own models for how that funding flows within the network and their governance arrangements (for example, whether to have a board, how to make sure practices are represented adequately and can hold both the network and each other to account). Five potential options are set out in the BMA’s PCN handbook. All have different implications for VAT and employment liabilities (for the new staff), and the degree to which practices may or may not be happy to trust a lead practice, federation or third-party organisation to manage the PCN funding on their behalf.

While the freedom to determine what works best locally makes sense, these decisions will have been challenging to make in the limited time available, not least because they have important implications for individual practices. In its guidance, the BMA states that ‘in all cases it is essential to take your own legal and financial advice on the potential legal and tax implications’. Mandating that networks form at such speed risks pushing them to make decisions based on what is most possible, or easy to do, rather than allowing time to consider how to best structure themselves to meet the needs of their populations.

For some parts of the country, in particular those with primary care homes or the early MCP vanguard sites, networks are already the norm in primary care. Some will already have strong cross-practice relationships, trust and understanding – all necessary foundations for successful collaboration. But in others, existing collaborations may not match the PCN requirements to be geographically contiguous or within the specified population size, and their service models may not match the requirements of the new network DES. Existing relationships may be strained as a result.

For areas without existing network structures, in the absence of organisational or leadership development support from NHS England, establishing PCNs will have been more challenging. PCNs with data-sharing agreements in place ready to deliver the extended hours requirements of the network specification on 1 July 2019 will receive £1.50 per head of core PCN funding backdated to 1 April 2019. This is a significant incentive to be ready ‘on time’, but areas with the strongest existing network structures are most likely to capitalise on the offer, while others that face the longest road to network formation might receive less funding for the start of the journey.

Getting organisational forms right will be necessary, but not sufficient, to produce high-functioning PCNs. Lessons from the Health Foundation’s improvement programmes have included the importance of teams having the time and skills to design, implement and sustain new ways of working. NHS England has been keen to leave the choice of which professionals to employ, and their remits, up to individual networks, but without careful implementation the benefits of expanded clinical teams are not guaranteed. The speed of implementation means that NHS England has not yet made any comprehensive organisational development support available to networks, and there is no leadership development offer for clinical directors (who may have been selected from a relatively small pool of available and willing GPs within a network). These resources are in development, but are large omissions that need to be rectified quickly.

PCNs are being developed within a context of wider changes in NHS structures. Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs), themselves relatively new, are rapidly evolving into ICSs, and the wider architecture of the NHS is shifting quickly. These overlapping initiatives, which must eventually work seamlessly together if their ambition is to be realised, add to the complexity of implementation.

Funding

Although the majority of practices stand to benefit financially from network participation, there are concerns that this will not universally be the case. PCNs will self-determine the distribution of network funds across member practices, making it hard to generalise about the implications for individual practices. Possible risks include:

- The removal of other sources of income for practices. To cover the cost of providing core PCN funding (which must come from CCG core allocation) CCGs may remove other payments available to practices (for example, some locally incentivised schemes). If income available to individual practices from enhanced services is reduced in order for CCGs to afford to pay networks, it is possible that funding to individual practices may fall.

- Payment for the clinical director role is being made on a whole-of-England average – but GP salaries vary by locality. PCNs in areas with high salary costs may find themselves out of pocket in reimbursing clinical director time, particularly if they face a ‘double whammy’ of needing to employ additional GP cover to fill clinical sessions vacated by the clinical director.

- Under the ARRS, NHS England has promised to meet 70% of the costs of employing most additional staff, but networks will be expected to meet the remaining 30%. This may be more feasible for some networks than others, and therefore ability to unlock the potential benefits of additional staff may vary between networks depending on their underlying financial positions. Financial liability for the new roles, for example in the case of redundancy, will also sit with the practices in the network.

Workforce and workload

Increasing the skills mix in primary care is intended to relieve pressure on GPs. Although NHS England recognises that more GPs need to be recruited and has put plans in place to accelerate this, progress is slow. There is an additional risk that PCNs might decrease the amount of GP time available for direct patient-facing activity.

Clinical directors are being funded at 0.25 WTE (on the basis of an average network size of 50,000). If this would otherwise have been patient-facing time for the clinical director, then the loss to a practice of over 1 day of consulting time each week is not insignificant. New staff such as pharmacists and physiotherapists will also need to be supervised by GPs. This is both a contractual obligation and a requirement for patient safety, but supervision, particularly with new staff, is an additional draw on GP time. Perversely, areas with the fewest GPs – where there may be greatest reliance on allied health professionals – will require proportionately more of the GPs’ scarce time to be spent on supervision.

There are also unanswered questions about how realistic the PCN workforce plan is. NHS England is confident that 20,000 additional allied health professionals will be available in time, but there are no data available in the public domain to allow us to model or verify these projections. NHS England has not stated how many of each type ofprofessional is expected, but the scale of the increases required will be large. In September 2018, there were only 55 physiotherapists, 99 physician associates and 428 paramedics working in general practice in England.

Increasing the primary care workforce means more then just increasing headcount. Appropriate workspace must be found to accommodate the new workforce, and this is likely to be a challenge in some GP surgeries. It is not yet clear whether additional funding will be made available to ensure that practice premises are fit for their expanded purpose, but is likely to be needed.

Inequalities

The inclusion of a PCN service specification on inequality is a welcome signal that networks will be a core part of the increased efforts to tackle health inequalities, as set out in The NHS long term plan. But aspects of the way PCNs are currently designed risks exacerbating existing inequalities in the provision of primary care.

The Carr-Hill formula – used to weight funding for GP practices – has been criticised for not sufficiently taking the effects of deprivation into account. Despite promises from NHS England and the BMA to address this, the new GP contract has not done so. As a result, the weighted component of per capita funding for PCNs is based on a formula that may systematically under-fund practices with the most need. Furthermore, some PCN payments are not weighted at all, such as the annual uplift of £1.50 per patient from CCGs for networks and funding for extended hours.

There is a commitment that in future PCNs will be able to unlock extra funding from an Investment and Impact Fund – essentially a savings scheme accessible to networks able to achieve specific targets. Examples of what these targets might be include reductions in A&E attendances and delayed discharges, but these are likely to be systematically easier to achieve in some populations. There might be ways to mitigate this (by offering more money per unit of achievement in deprived areas, for example) but this will require action from policymakers.

It is already clear that the workforce crisis in general practice is disproportionately affecting deprived areas. Between 2008 and 2017, the number of GPs working in areas containing the most deprived quintile of the population fell by 511, while 134 additional GPs were recruited to the areas containing the most affluent quintile. The ability of PCNs to deliver the services that will eventually be required of them is contingent on the successful recruitment of allied health professionals. NHS England is confident that there will be enough staff, and that this can be achieved without pulling staff away from secondary care. But even assuming that the promised 20,000 additional staff will be available to PCNs, there are no mechanisms to level the playing field for recruitment. We calculate that the number of pharmacists working in general practice is already lower in more deprived areas. Although some professionals will choose to work in areas of greater need (and often greater workload) there’s a risk of perpetuating a situation in which PCNs serving the most deprived populations (with the greatest health needs) are least able to recruit. Funding through the ARRS is only unlocked when staff are in post: if networks in deprived areas are systematically less able to recruit, there will be a corresponding reduction in network funding. Where a PCN doesn’t use its full ARRS allowance to recruit into posts, the money will be retained by the CCG. This risks creating a perverse incentive for CCGs – themselves under significant financial pressure – to favour under-recruitment into PCNs.

Although the intention of PCNs is that working at increased scale will increase practice resilience, there is no evidence to suggest that this will necessarily or universally be the case. The number of practices closing has risen rapidly in recent years and the most affected areas have strikingly similar profiles. Areas with older populations and older GPs (often rural and coastal locations where attracting new staff has been particularly difficult) have borne the brunt of practice closures, often leading to increased pressure on remaining local practices. Geographically grouping practices might allow PCNs to offer more attractive and diverse job roles and to reduce workload by streamlining back-office functions. But where the entire geography of a PCN is an area of high deprivation, increasing inter-dependence between neighbouring practices that are already vulnerable risks a domino effect, where the failure of a single practice drags others down with it.

In networks with only small pockets of deprivation within more affluent areas, or where a very small area has a defined need (such as a practice specifically providing care to homeless people), a single practice serving that group may find itself and its specific needs isolated within a larger network of practices.

Evaluation and monitoring

CCGs (or NHS England local teams, where there are CCGs without delegated primary care commissioning) are responsible for overseeing the Network Contract DES registration process and assuring that PCNs deliver against the requirements of the DES. A Primary Care Network Dashboard is being developed to support this and should be introduced from April 2020.

This monitoring should set a baseline for delivery against contractual requirements, and should provide some accountability and transparency on what the new investment has produced in terms of services delivered and, ideally, outcomes. But comprehensive evaluation of PCNs is also needed. NHS England is working on an evaluation framework, and this must include metrics to capture process as well as performance, recognising the difficulty of evaluating a complex intervention within a complex system. The opportunity to design PCNs with evaluation in mind, and to commence evaluation at the outset, has already been missed.

The formation of PCNs also raises questions regarding the regulation of general practice. The Care Quality Commission has been considering how to approach the regulation of larger providers of general practice, and the current model of inspecting and regulating general practice based on assessment of individual practices may need adjusting to reflect monitoring and regulation of services being delivered at network level, as well as the extent to which practice engagement in network activity is viewed as a marker of quality.

Where next for PCNs?

The ambition of policymakers to scale up general practice is not new, but the scale and pace of the change required to deliver PCNs is. Implementing the networks in the context of major pressures in general practice represents a risk for NHS England. For PCNs to meet the broader objectives of policymakers for primary care, they are likely to require:

- funding – which must represent a genuine increase, distributed equitably

- the promised workforce – distributed equitably

- improved recruitment and retention of GPs

- time and support for implementation, including organisational development and leadership support

- meaningful monitoring, and a support offer for struggling networks

- the ability of the wider system – including nascent ICSs and established secondary care, community care and social care providers – to work collaboratively with PCNs.

Underpinning all of this is the importance of building relationships to create meaningful collaboration. PCNs require practices to move beyond their traditional boundaries. Sharing financial resources can both generate and strain relationships, and practices will have to trust each other if sharing both staff and data is to benefit patients.

From a policymaking perspective, PCNs may have evolved partly as a pragmatic solution to the difficulties in recruiting and retaining GPs – but the networks also contain a bold vision for the future of general practice and primary care. They are simultaneously a vehicle for stabilising general practice, and one through which significant change and service improvement is expected if the pledges of The NHS long term plan are to be met.

For patients and the public, much will depend on what happens once the agreements are in place and contracts put in motion. If PCNs meet national expectations, patients stand to benefit from access to a wider range of services through a stabilised general practice. Better use of medications, less reliance on hospital care and improved links with other services in the community are among the prizes on offer.

There is no one version of what success for PCNs will look like – and neither is it clear what failure would entail. It is patients who will feel the effects of either scenario. PCNs are a significant change within a complex system – and general practice isn’t embarking on it from a position of strength. The same need that has in part driven the formation of PCNs means that there will be little resilience left in general practice should they falter or fail.

It is vital that a safety net is created to identify and support PCNs that struggle, and to ensure that resources are distributed equitably, in proportion with deprivation and health need. The challenge of implementing PCNs must not be underestimated. Sufficient time and support must be given for genuinely collaborative relationships to develop in a part of the health system that has historically placed great value on its independence and close relationships with its patient population. Otherwise the breakneck pace of PCN implementation risks undermining the ambitions of the policy.

References

- Health Foundation, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust. Closing the gap: key areas for action in the health and care workforce. 2019. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-03/Closing-the-gap-key-areas-for-action-full-report.pdf

- NHS England. The NHS long term plan. 2019. Available from: www.longtermplan.nhs.uk

- NHS England and BMA. Investment and evolution: A five-year framework for GP contract reform to implement The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/publication/gp-contract-five-year-framework

- NHS England. Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service: Contract specification 2019/20. 2019. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/publication/network-contract-directed-enhanced-service-des-specification-2019-20

- NHS England, British Medical Association. Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service, Guidance for 2019/20 in England. 2019. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/network-contract-des-guidance-2019-20-v2.pdf

- NHS England. Comprehensive model of personalised care [infographic]. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/publication/comprehensive-model-of-personalised-care

- NHS England. Five year forward view. 2014. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

- NHS England. General practice forward view. 2016. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf

- NHS England. Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. 2017. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf

- Kay A. The abolition of the GP fundholding scheme: a lesson in evidence-based policy making. British Journal of General Practice. 2002; 52(475): 141–4.

- Moran V, Checkland K, Coleman C, Spooner S, Gibson J, Sutton M. General practitioners’ view of clinically-led commissioning: cross sectional survey in England. BMJ Open. 2017;7. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/6/e015464.info

- Rosen R, Kumpunen S, Curry N, Davies A, Pettigrew L et al. Is bigger better? Lessons for large-scale general practice. Nuffield Trust; 2016.

- Kumpunen S, Curry N, Farnworth M, Rosen R. Collaboration in general practice: Surveys of GP practice and clinical commissioning groups. Nuffield Trust and Royal College of General Practitioners; 2017. Available from: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/collaboration-in-general-practice-surveys-of-gp-practice-and-clinical-commissioning-groups

- NHS England. Primary care networks: Frequently asked questions. 2019. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/publication/primary-care-networks-frequently-asked-questions

- Forbes L, Forbes, H, Sutton M, Checkland K, Peckham S. How widespread is working at scale in English general practice? 2019. Available from: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/73588/1/How%20widespread%20is%20working%20at%20scale%20in%20English%20general%20practice%20accepted%20BJGP%2016th%20April%202019.pdf

- Pettigrew LM, Kumpunen S, Mays N, Rosen R, Posaner R. The impact of new forms of large-scale general practice provider collaborations on England’s NHS: A systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 2018; 68(668): e168–e77.

- Hull S, Chowdhury TA, Mathur R, Robson J. Improving outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes using general practice networks: a quality improvement project in east London. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2014; 23(2): 171–6.

- Pawa J, Robson J, Hull S. Building managed primary care practice networks to deliver better clinical care: A qualitative semi-structured interview study. British Journal of General Practice. 2017; 67(664): e764-e74.

- Kumpunen S, Rosen R, Kossarova L, Sherlaw-Johnson C. Primary care home: Evaluating a new model of primary care. Nuffield Trust, London; 2017.

- Pettigrew LM, Kumpunen S, Rosen R, Posaner R, Mays N. Lessons for ‘large-scale’ general practice provider organisations in England from other inter-organisational healthcare collaborations. Health Policy. 2019; 123(1): 51–61.

- Fulop N, Protopsaltis G, Hutchings A, King A, Allen P, Normand C, et al. Process and impact of mergers of NHS trusts: Multicentre case study and management cost analysis. British Medical Journal. 2002; 325(7358): 246.

- Guthrie B, Davies H, Greig G, Rushmer R, Walter I et al. Delivering health care through managed clinical networks (MCNs): Lessons from the North. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme; 2010.

- Baeza JI, Fitzgerald L, McGivern G. Change capacity: The route to service improvement in primary care. Quality in Primary Care. 2008; 16(6): 401–407.

- Roland M, Barber N, Howe A, Imison C, Rubin G. The future of primary health care: Creating teams for tomorrow. Health Education England; 2015.

- Freeman G. Hughes J. Continuity of care and the patient experience. The King’s Fund; 2010.

- Barker I, Steventon A, Deeny S. Association between continuity of care in general practice and hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: cross sectional study of routinely collected patient data. BMJ. 2017; 365: J84.

- Ham C. GP budget holding: Lessons from across the pond and from the NHS. University of Birmingham; 2010.

- Le Grand J, Mays N, Mulligan JA. Learning from the NHS internal market. The King’s Fund Publishing; 1998.

- Smith J, Mays N, Dixon J, Goodwin N, Lewis R et al. A review of the effectiveness of primary care-led commissioning and its place in the NHS. Health Foundation; 2004.

- Goodwin N, Naylor C, Robertson R, Curry N. Practice-based commissioning: Reinvigorate, replace or abandon? The King’s Fund; 2008.

- Miller R, Peckham S, Coleman A, McDermott I, Harrison S et al. What happens when GPs engage in commissioning? Two decades of experience in the English NHS. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2016; 21(2): 126–33.

- Smith J, Sibthorpe B. Divisions of general practice in Australia: how do they measure up in the international context? Australia and New Zealand Health Policy. 2007(4); 15.

- Scottish School of Primary Care. Evaluation of new models of primary care. 2018. Available from: www.sspc.ac.uk/media/media_573766_en.pdf

- Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, National Assembly for Wales. Inquiry into primary care: Clusters. 2017. Available from: www.assembly.wales/laid%20documents/cr-ld11226/cr-ld11226-e.pdf

- British Medical Association. The primary care network handbook. BMA; 2019.

- Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, Farley K, Wright K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2018(1); 7(4):e013384.

- Alderwick HA GL, Fichtenberg CM, Adler NE. Social prescribing in the U.S. and England: Emerging interventions to address patients’ social needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018; 54(5): 715–8.

- National Association of Link Workers. Getting to know the link worker workforce: Understanding link workers knowledge, skills, experiences and support needs. Connect Link; 2019. Available from: www.connectlink.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Released_NALW_link-worker-report_March-2019.pdf

- NHS Digital. General practice workforce, final 30 September 2018, experimental statistics. 2018. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services/final-30-september-2018-experimental-statistics

- Kontopantelis E, Mamas M, van Marwijk H, Ryan AM, Bower P et al. Chronic morbidity, deprivation and primary medical care spending in England in 2015–16: A cross-sectional spatial analysis. BMC Medicine. 2018; 16(1): 19.

- Campbell D. Poor lose doctors as wealthy gain them, new figures reveal. Guardian; 20 May 2018. Available from: www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/19/nhs-gp-doctors-health-poverty-inequality-jeremy-hunt-denis-campbell-deprived-areas

- Gershlick B, Fisher R. A worrying cycle of pressure for GPs in deprived areas [blog]. 8 May 2019. The Health Foundation; 2019. Available from: www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/a-worrying-cycle-of-pressure-for-gps-in-deprived-areas

- Wickware C. Revealed: 450 GP surgeries have closed in the last five years 2018. Pulse; 30 May 2018. Available from: www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/hot-topics/stop-practice-closures/revealed-450-gp-surgeries-have-closed-in-the-last-five-years/20036793.article