Introduction

People generally place more value on being healthy than on factors like income, careers or education. But, despite improvements in life expectancy slowing and health inequalities widening, societal goals are still described in terms of income, employment and economic growth, rather than in terms of people’s health.

The Health Foundation wants to see more action on the strategies that help people stay healthy. Good health has a significant influence on overall wellbeing. It allows people to participate in family life, the community and the workplace. It has value in its own right and it also creates value. Put simply, health should be viewed as an asset that is worth investing in for our society to prosper.

Although evidence of the conditions needed for people to live in good health is well established, policy action lags behind. The reasons for this are complex: different views exist on who is responsible for an individual’s health; there is a trade-off between spending on short-term needs and investment for longer, healthy lives in the future; and often the benefits and savings from interventions do not accrue to those who need to make the investment.

The Health Foundation believes health should be viewed as an asset to be invested in. We ask the question, what is the social and economic value of maintaining and improving people’s health? The answer will provide evidence of the long-term benefits of good health to the individual, society and economy. It will mark out the public spending that could be viewed as investment in the social infrastructure required for a flourishing society.

Building evidence on the social and economic value of health is not straightforward. Socioeconomic circumstances are themselves major determinants of people’s health outcomes. Also, the relationships between health, individual outcomes and population-level outcomes can be difficult to untangle.

This briefing has two purposes:

- It sets out the rationale for a more explicit focus on maintaining people’s health over the life course.

- It describes a research programme, funded by the Health Foundation, that will assess the effect of an individual’s health on their social and economic outcomes.

The programme is now underway and is expected to be complete by 2021. Research is also underway to develop a greater understanding of the mechanisms through which the wellbeing and health of people in a particular place can affect the social and economic prosperity of that place.

Investing in our health

Our society places little emphasis on good mental and physical health, despite it being a basic precondition for people to take an active role in family, community and work life. Although there is growing concern about stalling life expectancy, the existing wide inequalities in health outcomes tend to be overlooked.

Current patterns in health and health inequalities

The government measure of the relative deprivation of areas within England is known as the Index of Multiple Deprivation. It considers seven domains: income; employment; education, skills and training; health; crime; barriers to housing and services; and living environment.

Between 2014 and 2016, men from the most-deprived tenth of areas in England were expected to live almost 19 fewer years in good health than people from the least-deprived tenth of areas (Figure 1). This disparity in health outcomes is strongly correlated with the conditions in which people live.

This relationship is not new, but as the UK’s population ages the consequences are becoming more apparent. The government’s vision for the role of prevention in improving health supports the ‘ageing society grand challenge’ of the UK government’s Industrial Strategy: ensuring a 5-year increase in healthy life expectancy by 2035 and, in doing so, closing the gap between the most and least deprived.

A workforce that remains fit, healthy and working for longer can both increase tax revenues and decrease the costs of supporting an ageing society. However, health inequalities undermine these benefits. By 65 years of age, twice as many men from the most-deprived fifth of areas in England and Wales (21%) will have died as men from the least-deprived fifth (9%), reducing the size of the available workforce.,

Figure 1: Total male life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth by decile of Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2014–2016

Note: Life-expectancy estimates shown are calculated on a period basis.

Source: Health Foundation analysis using Office for National Statistics data

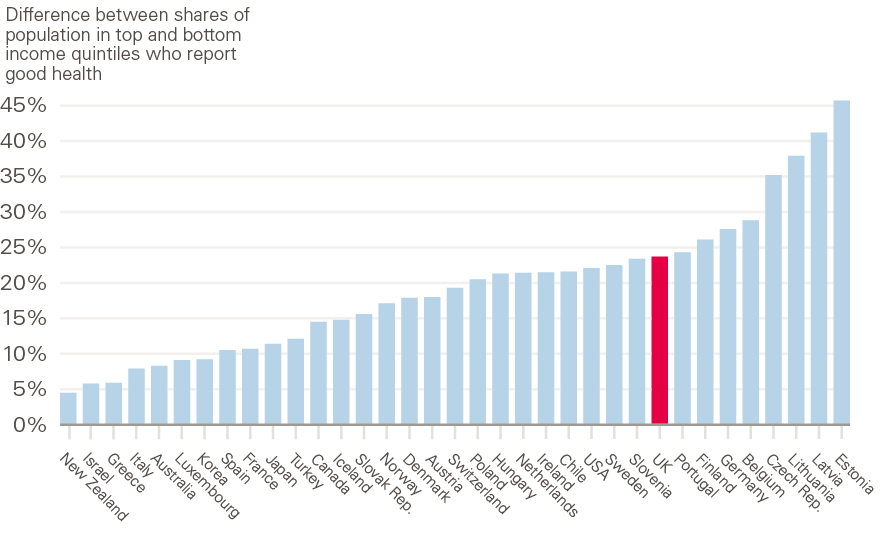

Such inequalities are not inevitable. Many countries have smaller inequalities in health outcomes than the UK. Figure 2 shows the difference in the percentages of national populations who report good health according to their household income bracket. In the UK, the share of the population in good health is 24% lower in the lowest income bracket than in the highest. The top-performing countries, such as New Zealand, Greece and France, have a gap of only 5–10%.

Figure 2: International comparison of health inequalities by income quintile

Note: Life expectancy is estimated on a period measure for 2016, except France, Canada and Chile (all 2015). Health measure is reported for 2016, except New Zealand (2014) and Chile (2015).

Source: Health Foundation analysis.

Strategies required to maintain and improve a population’s health

Compared with other policy challenges, such as the UK’s much-discussed productivity puzzle, the ways to improve health are well known: investment in early years development; lifelong learning; provision of good-quality, affordable housing; availability of high-quality jobs; public transport systems; and a food system that supports healthy choices. Sustained, cross-government efforts to reduce health inequalities during the 2000s were associated with reductions in differences in life expectancy across local areas in the UK. However, the investment and political focus necessary to continue, or at least maintain, such improvements have declined in recent years.

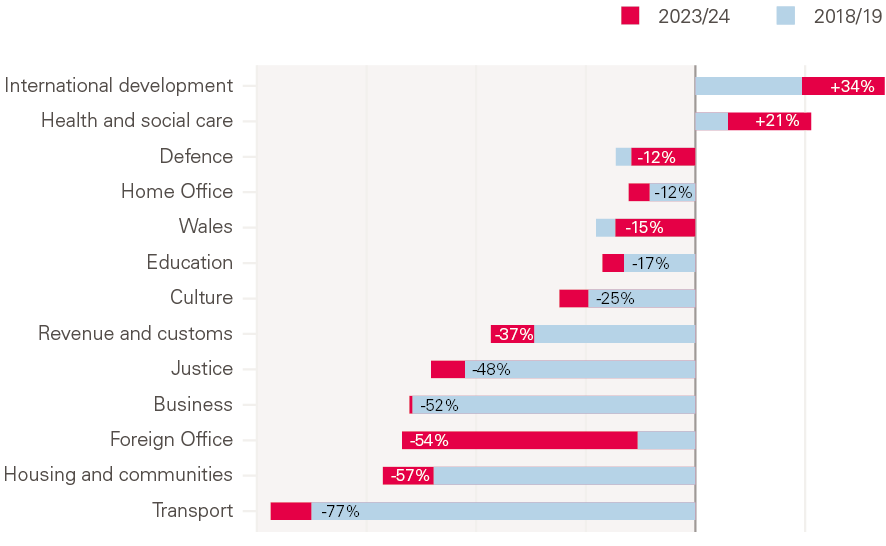

Government spending on day-to-day activities, such as teaching or the provision of health care, has fallen on a real-terms, per-person basis since 2010/11. The 2018 Autumn Budget signalled a change, setting a path for spending to grow over the next 5 years. However, despite the NHS England budget receiving a funding boost, day-to-day spending for most other government functions is expected to fall over the next 5 years, including those that support the maintenance and improvement of health. Additional funding for the NHS is important if future services are to be at least maintained, but prioritising health care spending will not, on its own, result in improvements in population health.

Figure 3 shows the extent to which departmental resources, such as transport, education and local government funding, have been squeezed since 2009/10.

Figure 3: Real-terms change in the resource budgets of government departments since 2009/10

Notes: Resource Departmental Expenditure Limit (RDEL) per person, gross domestic product (GDP) deflator.

These changes in government spending and the tight fiscal climate are not the only factors that have caused concern about people’s health. Other, wider shifts in the conditions in which people live and work can also make it hard to maintain and improve health. Household income growth has been weak in recent years. Incomes have only gradually recovered following the 2008 financial crisis – the average income of working-age households was only 4% higher in real terms in 2016/17 than a decade previously. Looking ahead to the beginning of the next decade, ongoing reductions to working-age benefits for low income families, especially those with children, are likely to result in a widening of income inequality, which is associated with health inequalities.

Although recent years have seen strong employment growth, the majority has been in full-time work. The increase in more insecure and low-paid forms of work has yet to reverse. Like low income, the insecurity that such employment brings can have a negative effect on health.

There have been changes in the types of housing families live in. Since the mid-2000s, there has been a large rise in the share of families living in the private rented sector. Accommodation standards tend to be lower than seen with home ownership and social housing, and private tenancy agreements tend to be shorter than social tenancies. Short tenancy agreements cause uncertainty and disruption in people’s lives. Looking ahead to the 2020s, reductions in state support for low-income families are likely to cause widening income inequalities, which we know are likely to lead to worsening health inequalities.

The effects of reduced investment in strategies that maintain and improve people’s health, coupled with the wider trends outlined above, are unlikely to be seen immediately, but the long-term consequences for people over their lifetime could be significant. Similarly, eroding people’s health risks declines in social and economic outcomes, which will affect wellbeing, living standards and ultimately the UK’s potential for growth.

How does good health contribute to social and economic outcomes?

A person’s health affects their social and economic outcomes. For children, healthy emotional, cognitive and physical development is important for good learning and educational outcomes, as well as for their ability to build supportive relationships in adult life., For adults, delaying the onset of avoidable long-term conditions is important for their chance of a full and active life.

Good physical and mental health can support social outcomes by allowing people to play an active role in the community – for example, socialising with family and friends, volunteering or voting. Good health has been associated with greater levels of social cohesion, although the evidence tends to relate to the impact of cohesion on health. Strategies that improve health can also deliver wider social benefits. For example, higher levels of education in an area are associated with lower levels of crime.

From an economic point of view, the health of the population can have a significant influence on its productivity and on a country’s output. Some of the largest effects of health on output have been found in countries with significant population-health problems, like malaria. In developed countries, the focus on productivity-related health tends to be related to absenteeism or keeping older people in work for longer. However, long-term, low-level health conditions (such as anxiety) are also likely to have an impact on an individual’s productivity. Research has also found that areas of the UK with high self-reported levels of health experienced quicker gross domestic product (GDP) growth. The extent to which health allows success in education means that health is a key determinant of job-related skills and knowledge, and therefore earning potential.

General value added (GVA) is a measure that captures the output of goods and services. It is similar to GDP, but excludes taxes and subsidies on products. Unlike GDP, it is available at a sub-national level, allowing local-area comparisons. Figure 4 plots the relative ranking of the GVA per hour against life expectancy. Lower life expectancy tends to be associated with lower productivity. However, both factors can influence the other, and the extent to which they do is difficult to unpick.

Figure 4: Life expectancy at birth for men compared with UK sub-region (NUTS2) ranking of gross value added (GVA) per hour worked, 2016

Note: Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 2 regions: Northern Ireland, counties in England, groups of districts in Greater London, groups of ancillary authorities in Wales and groups of council areas in Scotland.

Source: Health Foundation analysis.

Creating the conditions to improve people’s health

Policymaking that prioritises long-term investment in health

Helping people stay healthy is more cost-effective than waiting for people to become ill and dealing with the consequences. Yet, with a few notable exceptions, interventions are rarely implemented to their full potential. There are several reasons for this. Many interventions that support people’s health don’t show benefits for several years. When they do, the effects can be dispersed across the population, making them hard to prove using standard methods.

Political decision-making tends to be short-term, focusing on immediate needs and opportunities, and can overlook long-term consequences. For instance, where budgets are constrained, interventions with long-term benefits tend to be cut, as was the case for early years development.

It is rare to see effective, long-term change being proposed or enacted. One notable exception is the success of pension reforms. Cross-party consensus for change was achieved following the report of the Pensions Commission. This partly reflected the strong evidence base on which proposals were formed and the clear fiscal pressures a larger pensioner population would bring.

Cross-sector coordination

Levers for change are often held by decision makers whose focus is on outcomes other than improving people’s health. The government departments with policy levers related to housing, transport, supporting families on low incomes, food supply and environment are not rewarded for improving health. They have aims specific to their fields. However, their actions influence health outcomes because the conditions in which we live partly determine our health.

Employers also have an important role but, like government departments, have their own objectives. For example, the design of a new job is likely to focus on the most productive arrangements for a firm and not on the health effects of working conditions. Although employee wellbeing is becoming a higher priority for employers, the full effects of business and employment activities on people’s health are not addressed.

Coordinated action from government and employers – a health-in-all-policies approach – is a key step towards recognising health as an asset to be invested in.

Broader measures of success

Measures of society’s success tend to focus on the economy: for example, GDP, employment levels and household income. Given how important income is to our ability to use goods and services, and therefore to our standard of living, that makes some sense. However, the historic focus on GDP-based metrics and income as a proxy for use means those measures shape the design of government policy.

People’s happiness, wellbeing and health tend to be overlooked by policymakers. However, there are some signs of broader measures of success gaining traction. For instance, since 2012 the Office for National Statistics has regularly produced estimates of wellbeing. The Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 provides a legislative commitment for the Welsh government to improve the health of the population, and the Scottish Government’s National Performance Framework includes health improvements.

New Zealand has become the first country to commit to setting its budget based on wellbeing as well as economic growth. To assess progress, its government intends to use various measures of capital so that changes in social, environmental, human and health capital are considered alongside financial capital.

A unifying mission

There is a case for more sophisticated measures of economic and social progress to encourage action towards maintaining and improving a nation’s health. The World Bank’s new measure of human capital, the Human Capital Index, could inform debate about investment decisions. The Index is a potentially important tool for understanding variations in health by socioeconomic status and geography. Ultimately, it could be used to target investment where it will have the greatest impact.

The Index indicates the room for improvement in productivity by comparing existing levels of health and education in a country with a scenario in which those two factors are maximised. For example, a 15% difference in survival rates for UK men between those from the most and least deprived quintile on the Townsend deprivation scale would translate to a 29% gap in productive potential between men from the least-deprived and most-deprived areas.

Moving the agenda forwards

Limiting differences in health outcomes is a core principle of universal access to health care. The UK is privileged to have consensus on this principle. However, to address the current gap in healthy life expectancies, more attention must be given to creating conditions that allow people to lead healthy lives.

The relative lack of evidence for the value that good health delivers to wider society – both in social value and economic terms – is a barrier to achieving this shift. Building this evidence is complex, given the multi-directional relationships between a person’s health and their socioeconomic circumstances. The next section of this report outlines the first phase of a body of research the Health Foundation is funding to address this lack of evidence.

A research programme focusing on the socioeconomic value of an individual’s health

A complex relationship

The relationship between people’s health and socioeconomic factors

The greatest influences on people’s health are the social determinants of health – the social, cultural, political, economic, commercial and environmental factors that affect how people grow up, live, work and age. People living in deprived circumstances or with low levels of education have poorer physical and mental health. They live shorter lives and live more of their lives in poor health.

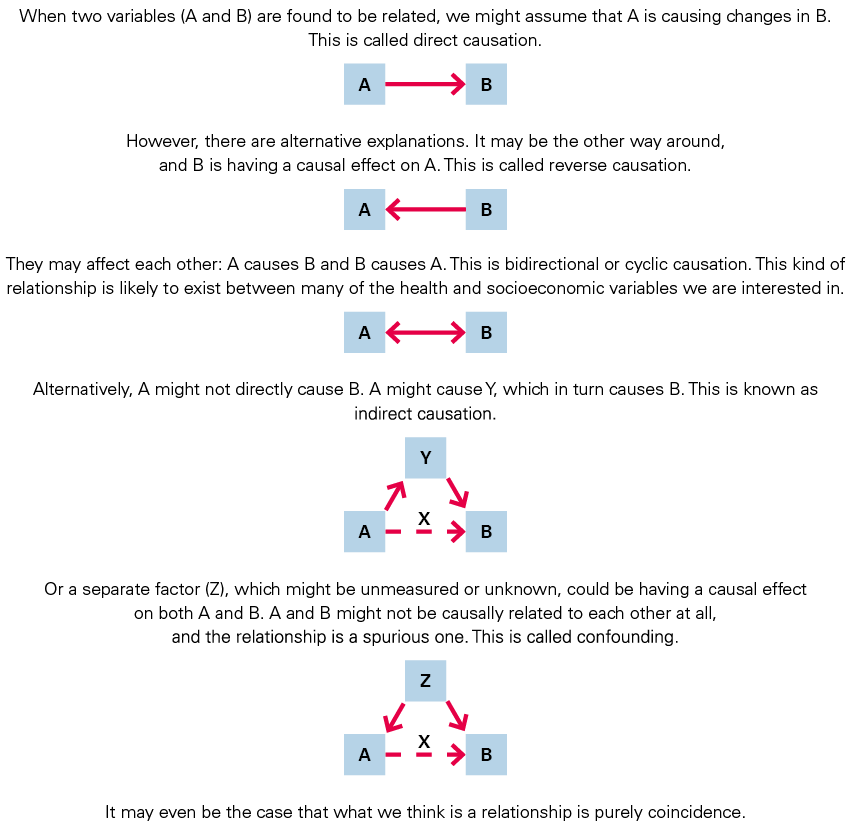

The relationship between socioeconomic factors and people’s health is complex: it is dynamic and multidirectional (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The dynamic relationship between health and socioeconomic factors

The multidirectional nature of the relationship is an opportunity to set up cycles of health and socioeconomic improvement. For example, keeping a child in good health could help them achieve their educational potential, increasing their chance of gaining good employment (red arrow). We know that good work is good for health (blue arrow).

However, cycles can also perpetuate health and socioeconomic inequalities. For example, a period of poor health can lead to a loss of work and income (red arrow). Low income can in turn lead to poorer health (blue arrow). Failure to invest in the maintenance and improvement of health via the social determinants of health risks such a cycle becoming established. Maximising health and socioeconomic potential requires a better understanding of the relationship.

There is a lack of evidence about the effect of people’s health and wellbeing on their socioeconomic circumstances (red arrow). Few studies have attempted to address the question of the socioeconomic value of maintaining good health across the life course. Where they have, unpicking the complex relationships has proven challenging.

Establishing causality

Understanding the relationships between health and socioeconomic factors is hindered by their complexity. The model of cause and effect is not simple or linear, and cannot be accurately described by the research methods and statistical models often used in population health research.

Health outcomes can be thought of as the consequence of numerous interactions between multiple interdependent parts of a connected whole. Such complex systems can mean that as one part of the system changes, another adapts – with potentially unexpected consequences. Complex systems are ‘defined by several properties, including emergence, feedback, and adaptation’.

It is relatively straightforward to demonstrate that different factors are associated with each other in individuals or populations, either at a single point in time or over a length of time. It can be tempting to assume that one factor causes the other. But association is not causation, and establishing whether a change in one factor causes a change in another is far more challenging. Attributing causality becomes particularly difficult when outcomes are distant in time from exposures, and multiple linked exposures and outcomes exist. To attribute causality, we first need to separate cause from effect, as well as the role of other factors at play (Figure 6).

The evidence for the socioeconomic value of health

Existing UK evidence

The Health Foundation commissioned University College London’s Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) to review the evidence on the effect health has on people’s socioeconomic outcomes and to identify what further research is needed.

UK research on the causal relationships between people’s health and their socioeconomic outcomes tends to be derived from longitudinal cohort studies. The cohorts are made up of people who were born at a given time and place and are followed up at intervals over the course of their lives. Data collection includes interviews, measurements and often blood samples. Cohort studies are rich sources of information about people’s lives, particularly health and socioeconomic factors.

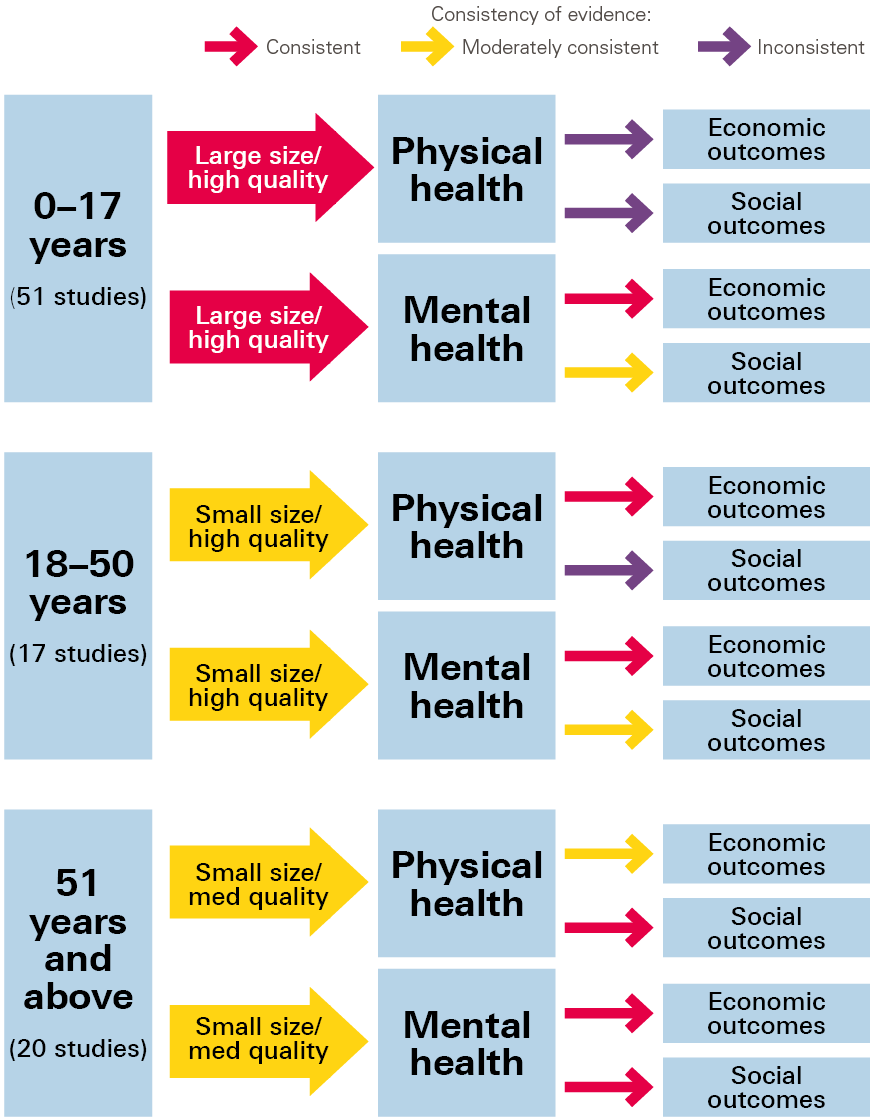

The CLS review included longitudinal cohort studies that explored the effects of health on socioeconomic outcomes. The review looked at three life stages: up to 18 years, 18–50 years, and over 50 years of age. Studies were assessed in terms of quantity, quality, and consistency of findings (Figure 7). Overall, the evidence was found to be limited and inconclusive, due partly to a lack of studies and partly to inconsistent findings. The inconsistent findings were often the result of the studies using different methodologies and data.

Figure 7: Quantity, quality and consistency of evidence for the causal effect of physical and mental health on socioeconomic outcomes at three life stages

Key gaps in the evidence

The CLS review revealed large gaps in our understanding of the causal effect of health on people’s individual socioeconomic outcomes. It also found there was scope in the rich, detailed data available in UK longitudinal cohort studies for future research:

- The effects of health on socioeconomic outcomes across the full lifespan could be assessed.

- Comparisons across cohorts could be made to see if the effects of health are changing across generations.

- Greater use could be made of the biomedical data already available in cohort studies.

- Causal relationships could be further investigated using novel statistical methods.

On the basis of these findings, the Health Foundation called for research proposals to explore the social and economic value of an individual’s health. The details of the chosen projects are detailed below. We are also developing a further call for research proposals to address how the health of a population in a particular place can affect the social and economic outcomes of that place. The call will go out in 2019.

The Social and Economic Value of Health research programme

What is the research programme?

The Health Foundation is funding six research projects that aim to better understand the causal effect of health on socioeconomic outcomes at the individual level. The research projects draw on the UK longitudinal cohort studies to address many of the identified gaps in the evidence. The effects of physical and mental health on a range of socioeconomic outcomes will be explored. Mental health will receive as much focus as physical health, and social outcomes are of equal interest to economic outcomes.

By comparing the socioeconomic outcomes of individuals with varying levels of health, the research will be able to draw conclusions about the value of maintaining good health across the lifespan. To assess causality, exposure must come before the outcome that is being measured. Using longitudinal studies, which follow up cohort members at a series of points over their lives, means the timing of the exposure can be identified. The dynamic relationships between health and socioeconomic factors mean, however, that they are likely to change in parallel. Knowing the timing alone will not allow us to draw conclusions about causality. The research projects will therefore use sophisticated statistical and analytical methods to establish causality.

What will this research programme tell us?

Some of the projects will look at a broad range of health inputs and socioeconomic outputs. Others will focus in detail on key health conditions (eg childhood obesity, common mental health problems) or socioeconomic factors (eg detailed employment outcomes).

It’s possible to assess so many exposures and outcomes because of the breadth of information in the cohort studies and because of data linkage. Linking data allows the researchers to look at administrative data (eg health service use or benefit payments) alongside self-reported and biomedical data.

A summary of the six research projects, an overview table, and technical details of the innovative research methods by which they will infer causality are available as an appendix on the Health Foundation’s website.

Inferring causality

All six projects will examine the complex, multidirectional relationship between people’s health and socioeconomic factors. The overall aim is to establish the causal effects of health on social and economic outcomes, separate from the effects that those factors can have on health, and separate from the effect of confounding factors. They will use recent developments in statistical methods, data availability (notably genetic data), and the ability to link data from different sources.

Aspects of time

The projects will investigate whether there are key times of life at which people’s health is particularly important. For example, are there times when a change in health has a bigger effect, and are there cumulative effects over the lifespan?

The projects will also focus on changes in the relationship between health and socioeconomic factors over time. As the prevalence of health conditions, the ability to manage them, and the socioeconomic context change over time, the strength and nature of the relationship between them might change. For example, an increase in obesity levels might reduce stigma and negative social outcomes, and the right to request flexible working might change the effect of health on a person’s ability to work. Some of the research will look across generations (via cross-cohort comparisons and intergenerational comparisons within cohorts) to see whether the relationship between health and outcomes changes over time.

The long-term data provided by the longitudinal studies will allow research into the long-term effects of people’s health on their socioeconomic outcomes. Some of the studies contain information about three generations of the same family, enabling researchers to look at possible intergenerational effects (eg whether parental mental health affects the employment of their children).

Modifying factors

It is likely that the relationship between health and socioeconomic factors varies by individual characteristics (eg education, level of deprivation, gender, ethnicity). The cohorts used by the researchers are large enough for them to explore many such factors. This could be important in understanding health and socioeconomic inequalities and how we, as a society, could mitigate or even prevent these inequalities.

Effects on others

The longitudinal studies include data on household members and their immediate families. Exploring this data could identify ‘spill-over’ effects on others, such as the socioeconomic consequences of caring for a relative with ill health.

Limitations

This briefing has already outlined the challenges of establishing causality. Although the six research projects will use innovative methods and varied data sources to address those challenges, this is a very new area of research. Considering the findings of the research programme as a whole – exploring the consistencies and differences – will give a better understanding of the relationship between health and socioeconomic factors and increased confidence in the projects’ conclusions.

What do we plan to do with the results?

The research projects began in 2018 and will be complete by 2021. The Health Foundation will regularly bring the researchers together to discuss interim findings.

Policy implications will be at the fore throughout the course of this work. The breadth of the research programme will allow us to consider the effects of health on a wide range of outcomes, as well as the importance of viewing health as an asset across different areas of government and sectors of the economy. We anticipate that the research programme will provide robust, comprehensive evidence about the social and economic benefits of investing in health.

More information on our Social and Economic Value of Health research programme, including updates and contact details of the lead researchers from each project, can be found on our website.

Conclusion

Making the changes needed to treat health as an asset, rather than as a by-product of other policy aims or the responsibility of individuals, will be far from straightforward. It will require not only a sea change in the approach government takes to policymaking, but also the involvement of employers, with health viewed as an asset to be invested in.

The Health Foundation’s Social and Economic Value of Health research programme will increase the evidence base for the contribution of good health to long-term socioeconomic outcomes. Understanding how and to what extent health affects wider outcomes will help us ensure people’s health becomes a core consideration in all policy.

- The Health Foundation is supporting and undertaking a range of research and analysis to help better understand and promote the population’s health as an asset that should be maximised.

- Through a £1.5m research programme, we are increasing the evidence base for the value of good health to social and economic outcomes.

- We are uncovering new evidence of the inequalities in people’s health and socioeconomic outcomes across the UK.

- A further, related programme of research will investigate the mechanisms through which people’s health affects the social and economic outcomes in a particular place.

- We are investigating the importance of good health for productivity and output.

- We are assessing the viability of the government’s Grand Challenge of improving healthy life expectancy by 5 years by 2035.

References

- Adler M, Dolan P, Kavetsos G. Would You Choose to be Happy? Tradeoffs between Happiness and the Other Dimensions of Life in a Large Population Survey. Centre for Economic Performance, 2015.

- Department for Communities and Local Government. The English Indices of Deprivation. Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015.

- Office for National Statistics. Health State Life Expectancies, UK: 2014 to 2016. Office for National Statistics, 2017.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Prevention is Better than Cure: Our Vision to Help you Live Well for Longer. Department of Health and Social Care, 2018.

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The Grand Challenges. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, 2018.

- Office for National Statistics. Life Table by Single Year of Age and Sex, by Townsend Deprivation Quintiles in England and Wales, 2009 to 2011. Office for National Statistics, 2017.

- Bibby J, Lovell N. What Makes us Healthy? An Introduction to the Social Determinants of Health. Health Foundation, 2017.

- Barr B, Higgerson J, Whitehead M, Duncan WH. Investigating the impact of the English health inequalities strategy: Time trend analysis. Br Med J. 2017; 358: j3310.

- Whittaker M. How to Spend it: Autumn Budget 2018 Response. Resolution Foundation, 2018.

- Allen M, Donkin A. The Impact of Adverse Experiences in the Home on the Health of Children and Young People, and Inequalities in Prevalence and Effects. UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2015.

- Dyson A, Hertzman C, Roberts H, Tuntill J, Vaghri Z. Childhood Development, Education and Health Inequalities. Institute of Health Equality, 2009 (www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/early-years-and-education-task-group-report/early-years-and-education-task-group-full-report.pdf).

- Gordeev VS, Egan M. Social cohesion, neighbourhood resilience and health evidence from New Deal for Communities programme. Lancet. 2015; 386: S39.

- Bruhn J. The Group Effect: Social Cohesion and Health Outcomes. Springer, 2009.

- Lochner L. Non-Production Benefits of Education: Crime, Health and Good Citizenship. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2011.

- Sachs JD. Institutions Don’t Rule: Direct Effects of Geography on Per Capita Income [No. w9490]. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2003.

- Ridge M. An Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Health on Aggregate Income and Individual Labour Market Outcomes in the UK. Health and Safety Executive, 2008.

- Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, Cookson R, Capewell S. Return on investment of public health interventions: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017; 71: 827–34.

- National Audit Office. Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities 2018. National Audit Office, 2018.

- Strategy and Constitution Directorate. Delivering for Today, Investing for Tomorrow: The Government’s Programme for Scotland 2018–2019. Strategy and Constitution Directorate, 2018.

- New Zealand Treasury. The Treasury Approach to the Living Standards Framework. The Treasury, 2018.

- World Bank. The Human Capital Project. World Bank, 2018.

- Health Foundation. Healthy Lives for People in the UK: Introducing the Health Foundation’s Healthy Lives Strategy. Health Foundation, 2017.

- Health Foundation. A Recipe for Action: Using Wider Evidence for a Healthier UK. Health Foundation, 2018.

- Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet, 390: 2602–4.

- Health Foundation. The Social and Economic Value of Health [webpage]. Health Foundation, 2018 (www.health.org.uk/programmes/economic-and-social-value-health).