Key points

- Over the past 12 years, the number of emergency hospital admissions in England has increased by 42%, from 4.25 million in 2006/07 to 6.02 million in 2017/18.

- Over 60% of patients admitted to hospital as an emergency have one or more long-term health conditions such as asthma, diabetes or mental illness.

- Patients with long-term conditions spend under 1% of their time in contact with health professionals. The majority of their care, such as monitoring their symptoms and administering medication and treatment, comprises tasks they or their carers manage on a daily basis.

- To find out how able patients currently feel to manage their health conditions, the Health Foundation looked at Patient Activation Measure (PAM) scores, which assess four levels of knowledge, skill and confidence in self-management, for over 9,000 adults with long-term conditions. We found that while 13% of patients reported the highest level of ability in managing their health conditions, almost a quarter reported the lowest level, and may feel overwhelmed by their conditions.

- We found that patients who were most able to manage their health conditions had 38% fewer emergency admissions than the patients who were least able to. They also had 32% fewer attendances at A&E, were 32% less likely to attend A&E with a minor condition that could be better treated elsewhere and had 18% fewer general practice appointments.

- Patients most able to manage a mental health condition, as well as any physical health conditions, experienced 49% fewer emergency admissions than those who were least able.

- These findings show the NHS could reduce avoidable use of health services, including the number of emergency admissions and A&E attendances, by supporting patients to manage their health conditions better. The potential impact of this is significant.

- If those currently least able to manage their conditions were better supported, so that they could manage their conditions as well as those most able, this could prevent 436,000 emergency admissions and 690,000 attendances at A&E, equal to 7% and 6% respectively of the total in England each year.

- Even if the patients who are currently least able to manage their conditions could be supported to manage their health conditions only as well as those at the next level of ability, this could prevent 504,000 A&E attendances, and 333,000 emergency admissions per year. This equates to 5% of total emergency attendances, and 6% of emergency admissions in England each year.

- In this briefing, we assess the evidence for the effectiveness of a range of approaches the NHS could use more often to support patients to manage their health conditions. These include: health coaching, self-management support through apps, social prescribing initiatives and peer support including via online communities.

- Previous studies have emphasised the importance of supporting patients to manage their conditions to improve health, wellbeing and satisfaction. Our findings show that the ability of patients to manage their health conditions impacts every part of the health service, but we believe the biggest opportunity to reduce avoidable hospital use lies in urgent care. To reduce emergency admissions and improve care for patients, national policy makers should provide greater support to patients so that they have the ability and confidence to manage their long-term conditions.

Introduction

Over the past 12 years, the number of emergency admissions in England has increased by 42%, from 4.25 million in 2006/07 to 6.02 million in 2017/18: an average growth rate of 3.2% each year. The health needs of patients admitted to hospitals are also becoming more complex: one in three patients has five or more health conditions compared to one in 10 patients a decade ago.

These increases in emergency admissions are concerning for three reasons. First, hospital admissions can expose a patient to stress, loss of independence and risk of infection, potentially reducing their health and wellbeing after leaving hospital. Secondly, many patients admitted to hospital would prefer to be treated at home or in a medical facility close to home – and, ideally, to avoid needing to seek urgent treatment in the first place. Finally, emergency hospital care is the most expensive element of the NHS and, in a cost-constrained system, needs to be carefully managed.

Many initiatives have tried to reduce emergency admissions, including extending access to primary care, using technology to direct patients to more appropriate sources of care, and enhancing primary care for residents of care homes and integrated care. While some interventions have shown some success, these have not stemmed the increases we have seen in emergency admissions.

New insights are therefore needed, and the Health Foundation has recently published analysis in BMJ Quality & Safety, which examines what the ability of patients to manage their conditions means for emergency admissions and other health care services.

The importance of supporting patients to manage their health conditions

Emergency admissions occur when a patient is admitted to hospital urgently and unexpectedly, either through A&E or by their GP or another professional. Many approaches to reduce these admissions have focused on changing how and where patients can access care, for example by increasing opening hours at GP surgeries or providing telephone helplines like NHS 111. Other approaches have sought to enhance or coordinate care for high-need patients,, , for example those living in care homes or with multiple health conditions. These changes might play a role in reducing the demand for some emergency care but we think they might miss an important part of the picture, namely how individuals are supported to manage their own health away from the NHS.

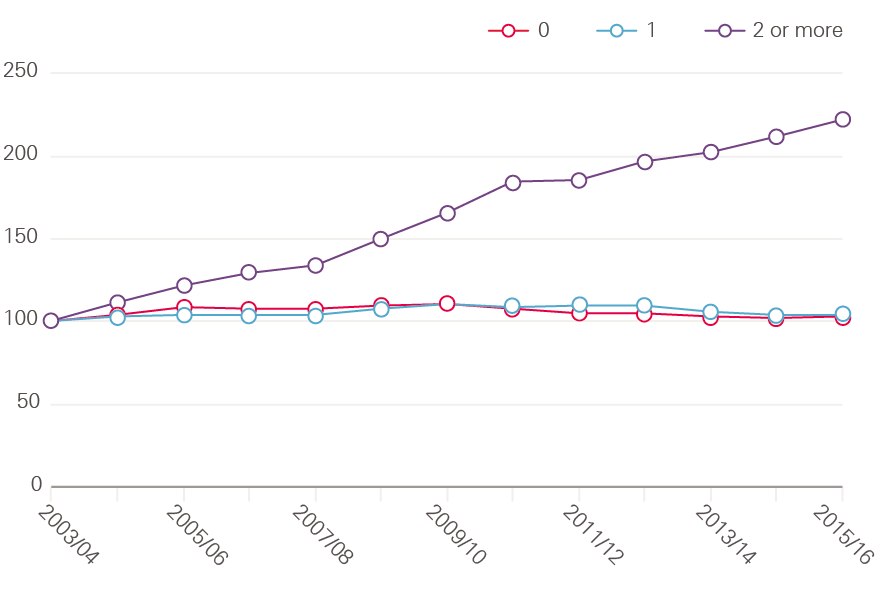

This aspect is relevant because so much of the increase in emergency admissions is linked to an increase in people living with long-term conditions, such as diabetes, heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Over 15 million people in England have a long-term condition, and while in 2006/07 40% of patients admitted as an emergency had at least one long-term condition, by 2015/16 this had risen to 61% of patients. In fact, the largest increases in hospital admissions are from those living with multiple long-term conditions. Between 2003/04 and 2015/16, while the number of admissions from those with one long-term condition has been relatively stable, admissions from those with two or more long-term conditions have increased by over 200% (Figure 1). Therefore, initiatives that focus on these conditions should be a particular priority.Figure 1: Relative change in the proportion of emergency admissions 2003/04 to 2015/16 for patients with zero, one or two or more long-term conditions (index 2006/07=100)

Patients with long-term conditions, and often their carers, are expected to manage these by themselves for much of their lives. Therefore, they need the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage these conditions, including the practical and emotional impact on their lives. But patients differ in their ability to manage their conditions.

For example, some do not have the knowledge about how to take their medicine correctly, the confidence to talk to their clinician and plan their care or the ability to manage flare-ups before the need for an emergency admission arises. This might lead to their health deteriorating more quickly than would otherwise be the case. It could also explain why there is consensus among expert health care professionals and patient groups that high-quality health care should support these patients to manage their own care – alongside other elements, like effective team care, planned proactive interventions and effective use of information systems.

These issues are becoming increasingly relevant due to technological advances. Many developments, including online support, apps and wearables, have the potential to create opportunities for patients to manage their health conditions, improve quality of life, and reduce reliance on secondary NHS care. But these opportunities may not be realised without a better understanding of people’s ability to manage their own health conditions, and this may determine how successful such new technology would be in reducing health service utilisation.

New findings: impact of patients' ability to manage their health conditions and NHS service use

Measuring the ability of patients to manage their health conditions

One way to measure patients’ ability to manage their health conditions is the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). This is a validated tool that measures the extent to which people feel engaged and confident, in taking care of their health conditions (Box 1). In 2016, NHS England agreed a five-year licence to use PAM with up to 1.8 million people as part of its work to provide personalised care for people with long-term conditions.

Box 1. How can you measure the ability of patients to manage their health conditions?

There are various methods available that measure aspects of patients’ ability to manage their own health. These include health literacy measures, which measure ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions’. However, there are many definitions and measures of health literacy, which is often complex to assess. Also notable are self-efficacy measures, which measure a patient’s belief in their ability to succeed in certain tasks and PAM, which measures a patient’s knowledge, skills and confidence in managing their own health and health conditions.

The PAM tool is licensed by the US company, Insignia Health LLC. Individuals are asked to complete a short survey and, based on their responses, they receive a score between zero and 100. The resulting score places the individual at one of four levels of activation, each of which is associated with a level of ability to manage their health.

We partnered with Islington Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) to examine what these PAM questionnaires are telling us about how patients with different levels of knowledge, skills and confidence use the NHS.

Islington CCG sent PAM questionnaires to over 35,000 patients living with long-term conditions in their area, asking them 13 questions about their beliefs, confidence in managing health-related tasks and self-assessed knowledge. Examples of such statements include: ‘I am confident that I can tell whether I need to go to the doctor or whether I can take care of a health problem myself’, ‘I know what treatments are available for my health problems’, or ‘I am confident that I can tell a doctor my concerns, even when he or she does not ask’. The PAM questionnaire could be filled in with the help of a carer but it was intended for the use of the patient themselves. A variation of the PAM questionnaire is available to address the needs of carers specifically, but was not used in this study.

9,348 patients (25%) returned the questionnaires. They were grouped into four levels of ability to manage their health conditions as described in Box 1. Here are real-life examples for illustration:

|

Level 1: |

Individuals tend to feel overwhelmed by managing their own health or health conditions, and may not feel able to take an active role in their own care. They may not understand what they can do to manage their condition better, and may not take their medication, attend preventative appointments, or see the link between healthy behaviours, such as smoking cessation, and good management of their condition. This group made up 22% of respondents in the Islington sample. |

|

Level 2: |

Individuals may be able to manage some aspects of their health (for example, take their medication and attend appointments) but still struggle in some aspects of their care, for example creating a care plan with their practitioner (19% of respondents). |

|

Level 3: |

Individuals appear to be taking action, for example setting goals for their health (such as adhering to a medically-advised diet) or creating a care plan with health care providers, but may still lack the confidence and skill to maintain these (46% of respondents). |

|

Level 4: |

Individuals have adopted behaviours and practices to manage their condition, such as good medication adherence, care planning or self-monitoring. Such individuals may be accessing support from online groups, peers and their community. Patients occasionally still need extra support, for example to recover from a relapse or a hospital procedure, or when other life stressors make it difficult to maintain their usual practices (13% of respondents). |

Our research examined whether patients assessed as having a higher level of activation were less likely to use primary and secondary health care than people who were less activated. Previous evidence in England was from a smaller sample of people surveyed by phone and international evidence has come largely from the United States, which has a very different health system. A previous qualitative study (funded by the Health Foundation) examined the feasibility of using PAM in the NHS, but evidence was needed on whether there was an association between ability to manage health conditions, as measured by PAM, and use of services across primary and secondary care. Until now no quantitative research existed from the NHS.

Our study provides insight, using large linked datasets for the first time, into the relationship between a patient’s ability to manage their health condition and their health care utilisation across primary and secondary care.

What’s the relationship between the ability of patients to manage their own health and emergency hospital admissions?

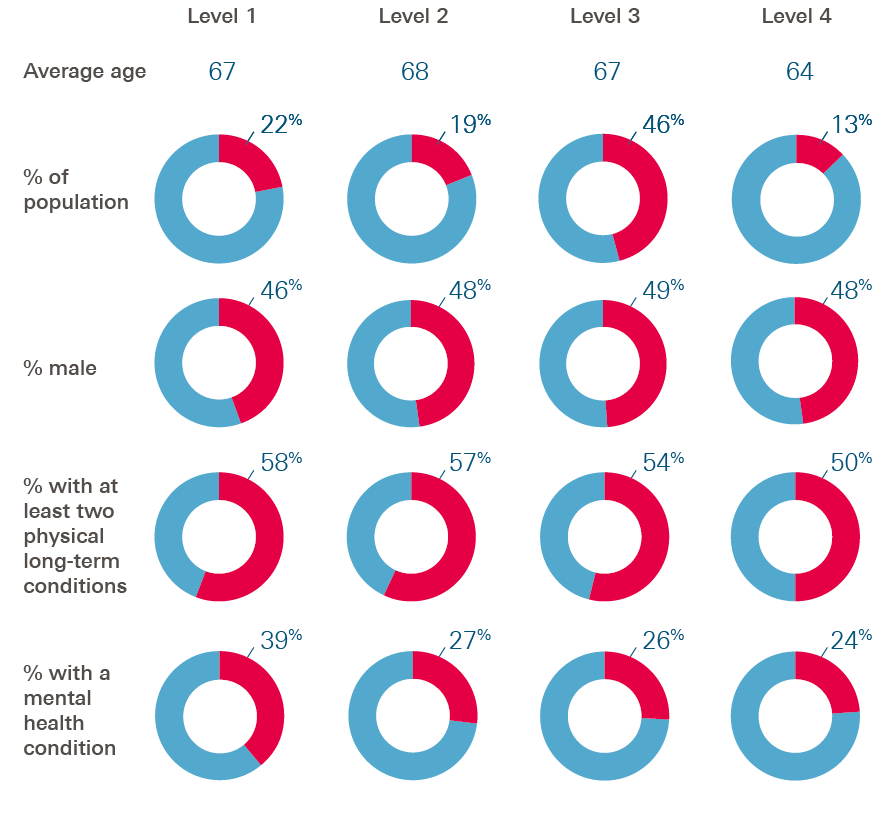

On average, the patients who were least able to manage their health conditions were aged 67 – 58% had two or more long-term conditions and 39% lived with a mental health condition. Just over half (55%) lived in the most socio-economically deprived areas in Islington.

In comparison, patients who were more able to manage their health conditions tended to be slightly younger and healthier, but otherwise had a similar profile (Figure 2). On average, they were aged 64, with 50% having two or more long-term conditions and 24% having a mental health condition. Half (50%) lived in the most deprived areas of Islington.

This suggests that patients can have low levels of ability to manage their health conditions regardless of their age and whether they live in affluent areas or more deprived ones.

Figure 2: Characteristics of patients included in our research study

We were interested in whether the patients most able to manage their health conditions used the NHS differently to patients who were least able. In making these comparisons, we were mindful that many patient characteristics affect demand for health care, including the number of long-term conditions, age, and whether they live in a deprived area. Therefore, we took these kinds of characteristics into account by building a statistical model. Our models effectively estimate the association between emergency admissions and the ability to manage their health conditions for patients with similar age, health and socio-economic status.

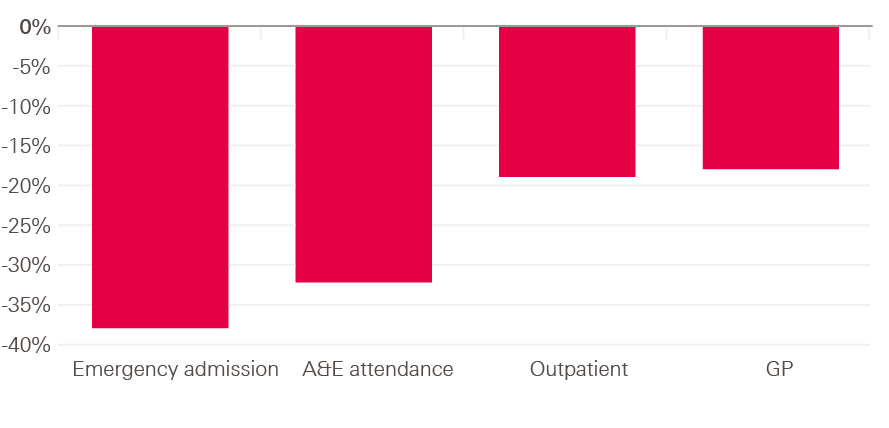

After controlling for characteristics in this way, we found that the patients who were better able to manage their health conditions experienced fewer emergency admissions (Figure 3). Those most able (PAM level 4) experienced 38% fewer emergency admissions than the patients who were least able to manage their health conditions (PAM level 1).

We also found that those best able to manage their health conditions were 32% less likely to attend A&E (with no emergency admission) compared to those least able. They were also 33% less likely to have attended A&E for a minor condition that could be appropriately treated in primary care. Patients a level higher (PAM level 2) had 29% fewer emergency admissions than those least able.

Figure 3: Difference in emergency admissions (% reduction) compared to patients in PAM level 1

Figure 4: Difference in health care utilisation (% reduction) – patients with PAM level 4 compared to patients with PAM level 1

What is the association between ability to manage health conditions and how often patients use general practice and elective care?

Emergency admissions are not the only example of where patients are using more health care. General practice workload is also increasing and health care leaders are also concerned about the volume of patients attending emergency departments without being admitted and the length of stay once they are admitted to hospital.

We found similar patterns for general practice appointments, elective admissions and outpatient appointments to those we found for emergency admissions (Figure 4). For example, compared with those least able to manage their health conditions (PAM level 1), the next most able (PAM level 2) had 8% fewer GP appointments, and 10% fewer outpatient appointments, while the most able group (PAM level 4) had 18% fewer GP appointments and 19% fewer outpatient appointments.

We also found that, once patients were admitted to hospital for elective care (which is often necessary for care of long-term conditions), length of stay was 41% shorter among the patients most able to manage their health conditions compared with those least able. One potential explanation is that more able patients can be discharged home with fewer supports, as they may be better able to understand and manage their medication and care without additional support from community or social care services.,

We also found that patients with higher levels of ability to manage their health conditions were less likely to miss their appointments with GPs and with outpatient clinics (Figure 4). This is important for two reasons: first, patients who are less able to manage their health conditions may be missing out on the health care that they need to prevent their condition deteriorating. Secondly, missed appointments are also potentially a waste of NHS resources.

Do we find the same pattern in those with a mental health condition?

Almost one in three (30%) of patients in our study had a mental health condition, such as depression, often in addition to a physical health condition, such as diabetes or asthma. When we analysed their data specifically, we found that those most able to manage their health conditions experienced 49% fewer emergency admissions than those least able and had 32% fewer A&E attendances. These findings were established after controlling for clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients in the statistical model. They suggest that there is heightened potential to reduce emergency admissions by improving the ability of patients with mental health conditions to manage their wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has many strengths, namely the large sample size, the fact that we had data about health care utilisation from across the NHS and that patients were registered for a long time with their GPs (median length of 15 years).

However, it has obvious limitations too. For example, information on the severity of people’s illness is not routinely recorded in health records and, while we have good information on levels of deprivation where patients live, we don’t have information on the individual support (such as family or friends) they can access. There is a chance that any association between self-management capability and health care utilisation is also influenced by support from families or social care that patients may have access to – something we were unable to measure. Finally, the questionnaire suffered from a low response rate, only 25% of patients were recorded as having returned it. The qualitative evaluation of PAM has also identified issues with the feasibility of administering the questionnaire using other methods – indicating that further work is needed to reach all patients. The low response rate and our analysis of respondents suggest that some patients, particularly those with high A&E attendance and low GP attendance, were less likely to return the questionnaire. This means that those who returned the questionnaire might not be comprehensively representative of the population living with long-term conditions in Islington.

What do these findings mean for patients and the NHS?

Patients living with long-term conditions, their advocates and many clinical experts have long recognised the importance of supporting patients to live well with their conditions, as part of high-quality, person-centred care. There is emerging evidence it may lead to patients having better clinical outcomes, improved wellbeing and more satisfaction with the care they receive. This alone is a reason that the NHS should invest in self-management support. However, when emergency admissions are rising, and demand for GP care outstrips an overstretched workforce, investing resources to support patients can be often overlooked. Our study demonstrates that this would be a mistake: it shows a clear link between the knowledge, skills and confidence a patient has to manage their health conditions, and their demand for health care, particularly emergency care.

If the group of patients who are currently least able to manage their conditions could be supported to manage their conditions as well as those who are currently most able, then the impact on the NHS could be as large as a reduction of 333,000–436,000 emergency admissions per year or 6% to 7% of the total number of these admissions. There could also be large reductions in the number of attendances at A&E, between 504,000 and 690,000 fewer per year or 5% to 6% of total attendances (Box 2). In our analysis in Islington, 32% of attendances at A&E were at the lowest level of activation, a quarter of which were for minor illnesses. This would equate to 2 million A&E attendances nationally, 544,000 of which could have been treated in primary care, suggesting that a large proportion of attendances could be avoidable. While it may never be possible for all patients to develop the skills and confidence to move to PAM level 4, some improvement in their ability – for example, moving up a PAM level – could have a noticeable impact on emergency admissions.

Box 2. Extrapolating our findings: methods

60% of patients admitted as an emergency in 2015/16 in England had at least one long-term condition – equal to 3.6 million emergency admissions per year.

Our analysis of patients with long-term conditions in Islington suggests that 32% of all emergency admissions are for patients at the lowest level of activation. Extrapolating this nationally, this translates to 1.1 million emergency admissions each year in England for these patients (32% of 3.6 million). Our analysis suggests that (controlling for patient and clinical characteristics) the patients most able to manage their health conditions had 38% fewer emergency admissions than those least able, or 29% fewer emergency admissions than those a level above. Therefore, there is potential to reduce the number of emergency admissions by between 333,000 and 436,000 per year, if patients who are currently least able to manage their health conditions were better supported so that they had the same ability as those better able to manage their health (29% and 38% of 1.1 million). This is equal to 6% to 7% of the total of admissions.

While exact figures are not available, if we assumed that 60% of the 10.9 million attending A&E without admission have a long-term condition, then this equates to 6.5 million emergency attendances. As those in the highest category of activation (PAM level 4) are 33% less likely to attend A&E, up to 690,000 A&E attendances could be avoided through increased support for self-management. More conservatively, those in PAM level 2 are 24% less likely to attend A&E, therefore up to 504,000 A&E attendances could be avoided if the least able (PAM level 1) were better supported to manage their condition. This is equal to 5% to 6% of the total of admissions.

However, strong caveats are attached to these estimates: first, we assume that our findings in Islington might be replicated across the country; secondly, we assume that all patients could become more activated and rely on effective interventions to achieve this. Finally, no intervention can be 100% effective so the full reduction is unlikely to be realised. That said, our selection of emergency admissions of patients with a long-term condition is conservative; more than 60% of patients admitted may have a long-term condition and there is also the possibility that activation could be improved within levels, as well as between them.

Box 3. Can self-management support always improve a patient’s ability to manage their health conditions?

The Health Foundation has previously published a practical guide to self-management support. This shows that providing information and access to tools (for example, online courses, electronic and written information material, patient access to medical records) is an important component of a health care system that encourages self-management support. However, such interventions alone may not improve a patient’s confidence and ability to put that information into practice. In contrast, other interventions, including health coaching and peer support, may improve a patient’s knowledge, skills and their confidence and, therefore, their ability to manage their health conditions.

Our study shows that there is a substantial proportion of patients whose ability to manage their health condition could be better supported and potentially improved. In the next section of this briefing we summarise some possible interventions and initiatives that could be introduced by commissioning services to unlock the potential of patients to self-manage.

Further information: interventions to improve the knowledge, skills and confidence of patients to ma

A range of approaches are available to support patients to better manage their health conditions. These are typically on a spectrum with some being more likely to improve patient confidence than others (Box 3). They can be split into two broad categories: the first supports patients to improve their knowledge, skills and confidence, while the second recognises that people’s ability to manage their health conditions will always be varied and tailors health services to meet these different levels of need.

Examples include:

Health coaching

About this

A trained health coach uses techniques such as reflective listening and motivational interviewing to support patients in face-to-face sessions or remotely. Coaches help patients to set health goals, such as remembering to take their medication on time or something more personal, such as walking to the shops or playing with their grandchild in the park. They then work with patients to achieve these goals, breaking them down into manageable, achievable steps. Coaching allows patients to identify their own strengths and assets, to access local support groups like gardening clubs and to adopt the most appropriate approach to managing their condition.

Health coaching is being trialled in a number of places in the NHS and has been included as part of the NHS Innovation Accelerator (NIA) programme. For example, in Horsham and Mid Sussex, and Crawley CCGs, health coaching is targeted towards patients at risk of experiencing emergency admission or requiring high levels of GP care or other NHS services. The coaching programme begins with the PAM questionnaire and is being delivered in partnership with GP practices, which help to refer patients to the service.

Evidence

There is some evidence from randomised control trials and systematic reviews that health coaching can be a successful approach to improving the management of long-term conditions., There is a need for studies regarding the impact of health coaching in the NHS, as these will help practitioners to design, implement and continually improve these services for patients.

Online communities

About this

Peer support can help people living with long-term conditions to keep healthy and online communities are increasingly becoming an important place to tap into it. Much like a disease-specific, face-to-face support group, an online community facilitates groups of people with the same long-term condition to connect, share stories and support each other. While it’s not a core aim, these virtual communities could potentially improve the ability of patients to manage their own health conditions (and so might help reduce emergency admissions).

One example is the online community HealthUnlocked, which has been supported by the NIA. HealthUnlocked hosts forums for a variety of health conditions, through which people can connect and share information. It collects a patient’s PAM score so it can tailor their advice and support, and provides resources from a range of partner organisations, including patient advocacy, charity and public sector organisations. These organisations also moderate online interaction and the advice shared.

Evidence

The evidence base for the effectiveness of online communities is still developing, with few studies published to date. More studies have examined the impact of peer support methods delivered face-to-face rather than online. This evidence is mixed, particularly for outcomes such as hospital admissions and readmissions, and whether peer support reduces length of stay.

Apps and online tools

About these

New developments in apps and online management tools might also help patients to improve their ability to manage their own health. The following are two examples of apps and online tools:

- myCOPD – a Health Foundation-funded resource for patients with COPD, providing information about the condition and a way for patients to monitor their symptoms online.

- Flo – a personalised text message system that helps patients with a variety of conditions monitor aspects of their health, and adopt and maintain healthy behaviours. Flo was originally funded by the Health Foundation and is now used by 70 health and social care organisations across the UK, with 33,000 patients registered.

Evidence

While there have been numerous evaluations of e-health interventions like Flo and myCOPD, these have often been focused only on small groups of patients. Larger evaluations of similar interventions have found conflicting evidence of reductions in emergency admissions. For example, the Whole Systems Demonstrator evaluated an older version of e-health that involved patients using technology to monitor aspects of their health and relay the information to health practitioners working remotely (telehealth). Although this trial concluded that those with long-term conditions receiving the intervention were admitted to hospital as an emergency 19% less frequently than control patients receiving usual care, there were significant concerns about the validity of the control group. Other studies using different methods have not found that these interventions were associated with lower rates of emergency admissions than usual care.

While the effectiveness of e-health and telehealth interventions has been found to vary, systematic reviews have found that they are more likely to be effective if they engage patients and include an element that is about supporting individuals to manage their own health conditions.

Tailoring services to the patient

About this

The second broad approach is based on the recognition that not everyone is able to manage their health conditions confidently and therefore the NHS could deliver health care that is tailored to varying needs. This approach may improve the quality of care that patients receive, even if it does not improve patients’ ability to manage their own health conditions.

In some areas of England, NHS teams measure the ability of their patients to manage their health conditions, so that care can be tailored. Indeed, the NHS has invested in PAM, which is being rolled out to 100 sites and made available to 750,000 patients. Examples of how PAM could be used to target interventions include:

- Patients who have lower levels of ability to manage their own health conditions could be prioritised to have additional time with skilled and trained team members. This additional contact time might focus on developing skills and knowledge while setting manageable goals.

- Meanwhile, patients who are more able to manage their own health conditions could be provided with information to help them manage their condition as part of a care plan. This might include signposting to electronic resources.

Evidence

In a project funded by the Health Foundation in South Tyneside, First Contact Clinical used PAM to tailor the care received by patients with COPD. Patients were offered varying levels of psycho-social interventions, with patients with the lowest PAM scores receiving the most intensive intervention.

These interventions included sessions with a trainee health psychologist or self-care practitioner, receiving information from a social-prescribing navigator, and receiving support from a community-based peer support group. The evaluation of 410 patients reported a positive impact on patients, including increased PAM scores and a reduction in GP visits. However, this evaluation was a before-and-after study with no control group, which can be susceptible to regression to the mean. A recent randomised control trial of a similar intervention found that while there was no impact on the participant’s PAM score or quality of life, patients receiving coaching used health care less often than patients receiving usual care. Overall, health coaching was found to be cost effective in that trial.

Conclusions

At a time when the NHS is under strain, there is a danger that the importance of supporting patients to manage their own health care might be neglected.

Our research suggests this might have negative consequences because supporting patients with long-term conditions to improve their self-management capability might reduce demands on both primary and secondary care, freeing up capacity within health care teams. Although the potential impact is hard to assess, one estimate, based on our research, is that if the patients who are currently least able to manage their conditions could be supported to manage their conditions as well as those most able then the impact on the NHS could be as large as a reduction of 333,000–436,000 emergency admissions per year – or 6% to 7% of the total number of these admissions. Not only would this save NHS resources, but it could reduce the exposure of patients to the potential strains of hospital stays, such as infections, and allow them to spend more time living well at home.

Overall, our findings show the importance of considering the variable ability of patients to manage their conditions when developing health policy across all sectors of care. Over 60% of all emergency admissions in England are from patients with at least one long-term condition. Yet, in this research just 13% of patients with long-term conditions felt knowledgeable about their health condition and said they were able to engage in healthy behaviours and confidently plan their care. In contrast, 22% of patients were likely to feel overwhelmed by the demands of their long-term condition and not take an active role in their own care. Without properly supporting patients, national policy makers may not achieve their goals to reduce the growing demand for emergency care in the NHS.

National and local decision makers, including commissioners and those designing urgent care services nationally in the NHS, need to:

- Recognise that there is a very broad spectrum of ability and confidence among people to manage their health condition, and this has consequences for health service use.

- Measure the knowledge, skills and confidence of patients to manage their own health condition. Measurement is needed both to track whether there have been changes over time for the population and to help NHS teams to tailor care to the needs of their patients. While PAM is currently used in 60 areas in England, continued and expanded investment in measurement, using PAM or another method,, is needed and would be most powerful if routinely linked with patients’ electronic health records.

- Implement approaches to support patients to manage their own health conditions. Some areas are implementing health coaching and goal setting with patients with long-term conditions – and NHS England is encouraging more areas to do this. The NHS could also do more to encourage patients to access peer support, including via online platforms.

- Understand that not all patients may be able to fully engage with emerging opportunities in digital care without additional investment to improve their knowledge and confidence to manage their conditions.

- Ensure that interventions are carefully evaluated, so that NHS teams can learn from the experience of implementing these approaches and make further improvements to the quality of the care delivered. One successful model is the Improvement Analytics Unit, which is an innovative partnership between the Health Foundation and NHS England that provides a free evaluation service to NHS providers, their partners and commissioners.

- Plan for the variable ability of patients to manage their conditions when implementing any policies to manage demand for NHS care.

For more information about our research, see the full paper, published in BMJ Quality & Safety and available to download from their website: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007635

References

- Steventon, A., Deeny, S., Friebel, R., Gardner, T. & Thorlby, R. Emergency hospital admissions in England: which may be avoidable and how? The Health Foundation (2018). Available at: www.health.org.uk/publication/emergency-hospital-admissions-england-which-may-be-avoidable-and-how

- Krumholz, H. M. Post-Hospital Syndrome – An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 100–102 (2013).

- Barker, I., Steventon, A., Williamson, R. & Deeny, S. R. Self-management capability in patients with long-term conditions is associated with reduced healthcare utilisation across a whole health economy: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health records. BMJ Qual. Saf. (2018). Available at: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007635

- Huntley, A. et al. Which features of primary care affect unscheduled secondary care use? A systematic review. BMJ Open 4, e004746 (2014).

- Huntley, A. L. et al. Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam. Pract. (2013). doi:10.1093/fampra/cms081

- Huntley, A. L. et al. A systematic review to identify and assess the effectiveness of alternatives for people over the age of 65 who are at risk of potentially avoidable hospital admission. BMJ Open 7, (2017).

- Salisbury, C. et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: a pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. The Lancet (London, England) 392, 41–50 (2018).

- Coleman, K., Austin, B. T., Brach, C. & Wagner, E. H. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 28, 75–85 (2009).

- Ellins, J. & Coulte, A. How engaged are people in their health care? Findings of a national telephone survey. The Health Foundation (2005). Available at: http://picker.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/How-engaged-are-people-in-their-health-care-....pdf

- Hibbard, J. & Gilburt, H. Supporting people to manage their health: An introduction to patient activation. The King's Fund (2014). Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/supporting-people-manage-health-patient-activation-may14.pdf

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Health Literacy. Measures of health literacy: workshop summary (2009).

- Mishali, M., Omer, H. & Heymann, A. D. The importance of measuring self-efficacy in patients with diabetes. Fam. Pract. 28, 82–87 (2011).

- Armstrong, N., Tarrant, C., Martin, G., Manktelow, B., Brewster, L. & Chew, S. Independent evaluation of the feasibility of using the Patient Activation Measure in the NHS in England (2017). Available at: https://lra.le.ac.uk/bitstream/2381/40449/2/PAM%20learning%20set_final%20evaluation%20report_final.pdf

- Dharmarajan, K. et al. Association of Changing Hospital Readmission Rates With Mortality Rates After Hospital Discharge. JAMA 318, 270 (2017).

- Horwitz, L. I. Self-care after hospital discharge: knowledge is not enough. BMJ Qual. Saf. 26, 7–8 (2017).

- Wood, S., Finnis, A., Khan, H. & Ejbye, J. At the heart of health: Realising the value of people and communities. Nesta (2016). Available at: www.nesta.org.uk/report/at-the-heart-of-health-realising-the-value-of-people-and-communities

- de Iongh, A., Fagan, P., Fenner, J., & Kidd, L. A practical guide to self-management support: Key components for successful implementation. The Health Foundation (2015). Available at: www.health.org.uk/publication/practical-guide-self-management-support.

- Thom, D. H. et al. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 11, 137–44 (2013).

- The Evidence Centre and Health Education East of England (2014). Does health coaching work? Summary of key themes from a rapid review of empirical evidence. The Evidence Centre and Health Education East of England. Available at: https://eoeleadership.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/Does%20health%20coaching%20work%20-%20a%20review%20of%20empirical%20evidence_0.pdf

- NHS Innovation Accelerator Economic Impact Evaluation Case Study: HealthUnlocked. Available at: https://nhsaccelerator.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/HealthUnlocked-Economic-Case-Study-YHEC-August-2017.pdf

- The Health Foundation. My COPD solution. Available at: www.health.org.uk/programmes/shine-2012/projects/my-copd-solution. (Accessed: 31 May 2018)

- Cottrell, E., Chambers, R. & O’Connell, P. Using simple telehealth in primary care to reduce blood pressure: a service evaluation. BMJ Open 2, e001391 (2012).

- Available at: https://health.org.uk/content/overview-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system-flo

- Steventon, A. et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ 344, e3874 (2012).

- Steventon, A., Grieve, R. & Bardsley, M. An Approach to Assess Generalizability in Comparative Effectiveness Research: A Case Study of the Whole Systems Demonstrator Cluster Randomized Trial Comparing Telehealth with Usual Care for Patients with Chronic Health Conditions. Med. Decis. Making 35, 1023–36 (2015).

- Steventon, A., Ariti, C., Fisher, E. & Bardsley, M. Effect of telehealth on hospital utilisation and mortality in routine clinical practice: a matched control cohort study in an early adopter site. BMJ Open 6, e009221 (2016).

- Salisbury, C. et al. TElehealth in CHronic disease: mixed-methods study to develop the TECH conceptual model for intervention design and evaluation. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006448

- NHS England, Patient activation sites. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patient-participation/self-care/patient-activation/licences/pa-sites/#chiltern. (Accessed: 31 May 2018)

- The Health Foundation. Psycho-social interventions to improve self-management of long-term conditions. Available at: www.health.org.uk/programmes/innovating-improvement/projects/psycho-social-interventions-improve-self-management-long. (Accessed: 31 May 2018)

- Panagioti, M. et al. Is telephone health coaching a useful population health strategy for supporting older people with multimorbidity? An evaluation of reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness using a `trial within a cohort’. BMC Med. 16:80 (2018).