Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this work, in particular: Alison Giles, Danielle Costigan, Hannah Graff, Rebecca Stacey and Modi Mwatsama from the UK Health Forum for producing the original case studies; and Jane Landon, who was previously at the Health Foundation, for synthesising the findings.

The case studies in this publication are adapted from the full versions, available at http://ukhealthforum.org.uk/project/february-2019-international-case-studies

Overview

With improvements in life expectancy stalling and inequalities in healthy life expectancy widening, there is growing recognition across the UK of the importance of improving and maintaining people’s health and reducing health inequalities. It is clear this cannot be achieved from action by the ‘health’ system alone.

People’s health is, to a large extent, shaped by the social, economic, commercial and environmental conditions they live in – the wider determinants of health. People who experience health-promoting conditions, such as a good education, high-quality employment, a decent and secure home, and strong, supportive relationships, are more likely to lead long, healthy lives than those without such opportunities. Whether through transport, housing, or fiscal or employment policies, decisions taken by national and local governments have the potential to create the conditions for healthy lives, or indeed erode them. Thus, there is a need for whole government strategies to create conditions that enable people to lead healthy lives.

‘Health in all policies’ is an established approach to improving health and health equity through concerted cross-sector action on the wider determinants of health. This collection of case studies illustrates practical attempts to do this around the world, from Australia to Canada. Some show national initiatives, while others focus on action taken in regional or local authorities. Each project achieved different successes and demonstrated various challenges, and all offer valuable insights into implementing health in all policies for the UK and beyond.

The collection is not designed to be prescriptive, but aims to stimulate ideas, generate discussion, and share knowledge and experience from around the world.

Background to health in all policies

Governments across the globe have responsibilities for the health and wellbeing of their citizens. In 2013, at the Eighth Global Conference on Health Promotion – organised by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Finland’s Ministry of Social Affairs and Health – governments endorsed a definition of health in all policies (see the box below). This important step built on decades of international work to improve health and equity through the wider determinants of health.

Box 1: Defining health in all policies: the Helsinki Statement

'Health in all policies is an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity.'

The aim of the statement was to encourage a pragmatic, systematic approach to embedding health and health equity considerations across sectors, policies and service areas. In practice, the approach may entail collaboration between two or more parts of government, or it may involve stakeholders outside government, such as businesses and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations.

A health in all policies approach should consider the perspective and priorities of the non-health policy area, such as transport or housing policy, when developing strategies to improve health. For example, by aiming to reduce traffic congestion, it is possible to work through the strategies that will both achieve this goal for transport departments and deliver wider health benefits, such as through reduced air pollution and more active travel. By considering other sectors’ priorities and constraints from the outset, participants are best able to capture the full range of health improvement opportunities their sector offers, and to show how such a sector’s core activities are relevant to health, rather than appearing to add health activities to the department’s existing work.

A health in all policies approach is built on the principle of co-benefits: all parties that contribute should benefit from being involved. As well as improving health and health equity, partnerships should support other sectors to achieve their own goals, such as creating good-quality jobs or local economic stability. At the same time, a healthier population is likely to bring social and economic benefits to other sectors in the long term. This offers further rationale for cross-sectoral investment.,

Making this happen in practice is not simple. Working across sectors to improve health presents several challenges for traditional models of public policy. The policymaking process is rarely a linear path from ideas to implementation, and the process can become even messier when policy problems are complex, affected by multiple factors, and require a coordinated response across departments and over time. Policy partnerships often struggle to navigate the cultural, organisational and accountability issues they face. There is therefore value in taking a systematic approach to learning from past experiences of implementing health in all policies.

The UK context

In the UK, various pieces of legislation give public bodies duties around improving health and reducing inequalities. For example, in England the Health and Social Care Act 2012 confers on local authorities a duty to improve health in their localities, and the Social Value Act 2012 requires the public sector to consider economic, environmental and social wellbeing when commissioning services.

Wales and Scotland have gone further and created their own separate national frameworks for assessing the impact and value of policy decisions on health and wellbeing. In Wales, the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 aims to improve the country’s social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing. It places a duty on a wide range of public bodies, including government ministries, local authorities and local health boards, to work towards seven wellbeing goals: prosperity, resilience, health, equity, community cohesion, a vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language, and global responsibility. The act also sets out five principles for ways of working that public bodies should adopt to achieve the goals: long term, prevention, integration, collaboration and involvement. By enshrining these goals in legislation, the Welsh government aimed to embed health and equity considerations across all sectors. The act also established a Future Generations Commissioner to promote the sustainable development principle, acting as a guardian for future generations, and to hold public bodies to account for implementing their wellbeing objectives.

Scotland’s National Performance Framework was launched in 2007 and put into law in 2015. It is a wellbeing framework that reflects the Scottish people’s values and aspirations, that aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and that tracks progress in reducing inequality. It articulates 11 national outcomes – such as Scottish people growing up loved, safe and respected so they realise their full potential, and living in inclusive, empowered, resilient and safe communities – and tracks progress towards these outcomes through 81 economic, social and environmental indicators. The Scottish government uses the data to develop policy and services across Scotland.

In practice, there are increasing numbers of cross-sectoral collaborations for health at local and regional levels too. For example, since devolution of its health and social care budget in 2015, Greater Manchester has brought together NHS organisations, local authorities and other stakeholders to improve the population’s health, reduce inequalities and address growing demand for health services. The reforms have involved joining up public services in neighbourhoods, developing shared city-wide governance and decision-making processes, and pooling budgets to achieve mutually agreed goals by 2021, such as 16,000 fewer children living in poverty and 1,300 fewer people dying from cancer.

The Health Foundation, with NHS Research and Development, has funded an evaluation to explore the changes that followed Greater Manchester’s devolution and its impact on health, inequalities, and health and social care services. A qualitative analysis of the first 18 months of devolution was published in 2018. It described stakeholders’ strong support for adopting a place-based approach and integrating public services to improve health, but noted a variety of challenges to implementing reforms. The evaluation’s quantitative findings will be reported in 2019.

There remains both scope and need for more cross-sectoral action. A health in all policies approach has not been implemented at the pace and scale many hoped for. National and local policymaking often fails to seize opportunities to improve health through non-health policy levers and does not account for the harmful health effects of non-health policies.

Why this publication?

Implementing a health in all policies approach is not without challenges, but much more can be done to unlock the potential of government and local authorities to improve health through cross-sectoral action.

Despite extensive literature on the barriers to, and facilitators of, health in all policies, there is a lack of pragmatic, context-specific evidence showing how actors have successfully built partnerships and why different approaches have worked or failed in different settings.

In recognition of this need, the Health Foundation commissioned the UK Health Forum to analyse international examples where national, regional or local governments have introduced social policies or programmes to improve health and reduce health inequalities through actions outside the health sector.

For each case study, the researchers explored the context in which the policy and action evolved, how the actors developed ideas and solutions, the motivation for and attitudes towards interventions, and what helped or hindered implementation. Finally, they reflected on what their findings might mean for the UK.

Methods

To identify the case studies, the research team initially consulted international public health research and policy experts, looking for examples of national, regional or local government-led policies or programmes, implemented from the year 2000 onwards, which aimed to improve health through non-health sector action. From a long list of 35 options, the team carried out detailed literature searches. They shortlisted those policies and programmes with clear evidence of: the intervention’s goals and the lead institutions; the outcomes or intended outcomes; the context in which the intervention was developed; and how the ideas and solutions came about. The final nine case studies were selected to provide a diverse range of non-health sector policies, countries and policy implementation levels.

For each case study, the researchers interviewed key stakeholders – either participants in the policy process or academics who had reviewed or evaluated the policy – who provided first-hand insights into what influenced the policy process, what did and did not work, and why.

The team analysed the findings in relation to several theoretical policy frameworks. They identified themes in each case study that helped explain how or why the intervention succeeded or failed and what this might mean for UK policy and practice. The researchers also looked for consistent themes between the case studies to generate more overarching learning points.

Lessons from the case studies

Claire Greszczuk, Tim Elwell-Sutton and Jo Bibby

The nine case studies offer valuable insights into the practicalities of delivering a health in all policies approach in different contexts and sectors, and at different levels of government. Each example offers ideas and learning points that policymakers and practitioners may draw on and adapt to design and deliver initiatives in their areas.

The collection demonstrates several critical ingredients for implementing and sustaining a health in all policies approach:

- Leadership, politics and events that align to create policy windows. For example, Paris saw a step change in action on air pollution when mayor Anne Hidalgo took office on a pledge to rid the city of diesel vehicles. Find out how Mayor Hidalgo led a package of ambitious policies to improve the air quality in Paris on page 24.

- Cross-sector and cross-government participation. For example, Norway’s approach to making health a cross-sector responsibility was through the Public Health Act 2012, which placed a duty on government departments at national, regional and local levels to incorporate health in policymaking and practice. Find out more on page 54.

- Framing the issue to secure stakeholders’ support. The case study on US action on prisoner reoffending illustrates how powerful public health messages can emerge in unexpected ways that capture widespread support for change. Read more about how President George W Bush promoted support for prisoners on page 37.

- Community involvement. For instance, extensive engagement with local stakeholders, including city residents, enabled the Swedish city of Malmö’s Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö to: identify the issues that mattered most to local communities, implement meaningful and realistic change, and bring people along from the start. Learn about some of the innovative actions taken in Malmö on page 15.

However, the initiatives did not always deliver the ambitions intended. The case studies highlight a multitude of complex barriers to delivering and sustaining cross-sectoral partnerships for health, which may explain why progress can be slow. The following challenges were common to many of the initiatives:

- Lack of alignment in incentives. Failure to adequately reward performance (which is especially important in situations where costs are incurred by one department and the benefits fall elsewhere), or a failure to frame goals in ways that engage non-health stakeholders, can prevent stakeholders participating. For example, although Norway’s Public Health Act required all government departments to consider health and health equity, the legislation alone was insufficient to embed health in all policies since stakeholders did not see how it would benefit their department. Continual influencing by the public health community was needed to garner support and explain how a health in all policies approach could deliver co-benefits to non-health sectors. Read more on page 54.

- Competing priorities. These can prevent collaboration and mean good intentions fall short when priorities change. For example, five years after Pennsylvania’s Fresh Food Financing Initiative was launched, the global financial crisis hit and the state could no longer fund the programme. Read more about what the programme achieved, and its legacy, on page 45.

- Maintaining the focus on health equity. Health equity can often get lost when health in all policies approaches are planned and implemented. This may be due to a lack of awareness of the difference between improving health and improving health equity, a lack of relevant data, or simply because not enough people experiencing inequalities have been involved in the process. For example, although South Australia’s social inclusion initiative had many successes, health inequalities had not changed 10 years on. Read more on page 30.

- Inability to make long-term investments. On page 15, the example of Malmö’s Commission to embed social sustainability across the city illustrates the way in which inflexible annual budgeting cycles can present a barrier to long-term investment.

- Limited evaluation. Failure to build in comprehensive evaluations, or a lack of suitable methods for assessing policy and programmes’ complex impacts, means initiatives may not generate learning for the future. For example, although the Healthy Canada by Design project (page 63) was rigorously evaluated over three years, this may have been too short a time frame to measure its health outcomes, especially since the urban planning process typically takes five to 10 years. Further, it was difficult to design an evaluation that would capture the project’s complex impacts in a way that could be attributed to the initiative.

Recent trends suggest the UK faces some formidable challenges in improving the length and quality of people’s lives. Many of the major public health issues of our times – rising child obesity, increasing mental health problems, and a growing number of environmental crises – arise from complex systems involving different sectors. Creating healthy lives, therefore, not only needs action outside the health system, but also an approach that goes beyond disease-specific strategies. Broad-based action is needed to improve the social, environmental, economic and commercial conditions in which people live. Is a health in all policies approach the right way to achieve that?

For some, the health in all policies concept has not lived up to its early promise. As these case studies show, there are many challenges and barriers to the approach but, when the right ingredients are present, such strategies can deliver tangible value for people’s long-term health. There is already visible leadership and innovative cross-sectoral working within the UK, in local authorities and at national levels, notably in Scotland and Wales. All these places, both at home and abroad, provide inspiration and insights that can support people and places everywhere to innovate, test and spread new approaches to creating healthy lives.

The Health Foundation’s Healthy Lives strategy emphasises the importance of cross-sector and whole government action. It argues that the good health of a nation needs to be viewed as an asset to society and the economy – one that should attract long-term investment that maintains and improves people’s health and addresses health inequalities. This will require all policy- and decision-makers to consider the value – or at times cost – of their actions to people’s health. Ultimately it will require government to be more accountable for the impact of policies on health, with health and wellbeing measures set on an equal footing to economic outcomes such as GDP. In short, health should be viewed as a shared value across government and beyond.

1. Embedding social sustainability across Malmö

Summary

With health inequalities causing social polarisation and a burden on services, city officials in Malmö, Sweden, established a commission dedicated to improving health equity and encouraging sustainable growth – socially, financially and environmentally.

Timeline

Context

Malmö is a large city in southern Sweden. It is one of the fastest-growing cities in Europe, but has substantial health inequalities. In the mid-2000s the gap in life expectancy between people with the highest and lowest levels of education was 5.4 years for men and 4.6 years for women, with the most educated experiencing the longest life expectancy. There was also a clear difference between the health of Swedish-born Malmö residents and those born abroad, partly due to unequal access to work and social services. For example, Malmö’s Iraqi population had high unemployment, were physically segregated in certain parts of the city, and had levels of obesity twice that of Swedish-born residents.

The intervention

Phase 1: The Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö

Inspired by the 2008 WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, the Malmö City Executive Board established the Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö in 2010 to reduce health inequalities and help the city grow sustainably in all social, financial and ecological aspects.

The Commission’s mandate was to reduce health inequalities through areas such as preschools, workplaces and urban design. The City Executive Board also had an ambition to work towards sustainable development from all perspectives, with a greater focus on the social dimension of sustainability.

Following its decision to establish the Commission, the board engaged in an extensive consultation process to determine its structure, scope, process and priorities.

The Commission began its work in 2011. It comprised 14 academic researchers and practitioners working in Malmö, and was coordinated by a dedicated secretariat of four people, including a general secretary and a communications manager.

The Commission initially undertook a comprehensive evidence-based analysis of health, health inequalities and the social determinants of health in Malmö, which it published in 31 reports. These reports served as discussion papers to facilitate dialogue and consultation with stakeholders within and beyond Malmö. Around 2,000 people, including representatives from the private sector, interest groups, professional organisations and city residents, took part in participatory action research through 30 public and private events. The findings informed the Commission’s final recommendations.

The Commission published its final report in 2013. Its overarching recommendations were:

- to establish a social investment policy to reduce inequalities in living conditions and make social systems more equitable

- to change processes by creating knowledge alliances and democratised management.

The Commission also recommended 72 specific actions grouped into six domains across the wider determinants of health. The domains were:

- everyday conditions during childhood and adolescence

- residential environment and urban planning

- education

- income and work

- health care

- transformed processes for sustainable development through knowledge alliance and democratised management.

Phase 2: Implementing the Commission’s policy recommendations

The recommendations from the Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö were supported at the highest political and administrative levels. In 2014, the City Executive Board invested SEK3.5m in promoting, coordinating and monitoring the Commission’s work and established a cross-sector steering group to oversee implementation.

A working group, comprising representatives from local government departments across the city, began the implementation by developing a framework of feasible actions that individual departments could work towards and be monitored on. A small team of civil servants supported implementation through a communications strategy, sharing knowledge and good practice, and coordinating and producing annual progress reports.

The Commission’s recommendations were implemented in a number of ways – for example:

- The planning department adopted more bottom-up approaches to engaging stakeholders in decision making. It also started using its procurement processes to strengthen social outcomes – for example, by employing local people in new renovation and building work.

- The culture administration conducted a mapping exercise to see who was accessing culture and leisure activities, and then worked to distribute them more equally. For example, Malmö City Theatre introduced mid-week daytime performances in schools to compensate for cutbacks in arts in the school curriculum.

- A social investment fund of SEK100m was established for city administrations to apply for policy or project funding. However, the requirements to estimate future cost savings were too complex for most applicants and did not match the annual budgeting cycle, and the fund was later abolished. Instead, the City Executive Board embarked on a programme to build capacity for economic evaluation within departments, with a view to introducing a new social investment fund in the future.

Evaluation

Between 2014 and 2016, the City Office undertook three annual progress reviews.,, The researchers used interviews and text analyses to assess whether specific language around social sustainability had been incorporated into local government policy documents.

The reviews suggested there had been incremental progress towards incorporating social sustainability into policies and practices across the city. For example, 50% of the actions were underway in 2015, rising to 84% in 2016. There were other examples of progress too:

- The City Office implemented a comprehensive suite of communications activities to raise awareness of the Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö and its recommendations.

- The annual city budgets demonstrated ongoing political and administrative prioritisation of social sustainability. For example, all committees across the municipality were tasked with making specific social sustainability investments.

- The city planning administration adopted a more bottom-up approach to involving communities in urban planning decisions.

- Efforts were underway to build teams’ knowledge, expertise and capacity for economic and social impact assessments, and policies were increasingly assessed for their social impacts.

- The city authorities demonstrated their commitment to social sustainability through establishing the SEK100m social investment fund.

- In 2018, the Office for Sustainable Development was established to oversee the city’s work.

In 2018, a formal evaluation of the Commission’s impacts on health inequalities and their determinants began. The findings have not yet been published, but the researchers recognise it will be challenging to attribute any observed changes in health inequalities to the Commission itself.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- Because health inequalities and their social and economic impacts had high visibility – both socially and structurally – there was strong public and political support for action.

- High-level political commitment has maintained social sustainability as a priority in Malmö.

- Many individuals and communities were engaged and committed to improving social sustainability in Malmö, and demonstrated this through creating networks and pooling resources. This was crucial for driving change.

What worked less well

- Measuring the impacts of social investments was difficult, partly because the benefits take a long time to be realised and because such complex interventions have wide-ranging effects across many sectors, which are rarely measured. For example, investment in children’s services may result in reduced input from social work, health care or criminal justice – but much further down the line.

- Financial constraints and budget deficits hampered investment in preventative measures since funding core operations was prioritised. Further, the annual budgeting, planning and measurement cycle made it difficult to invest in more long-term approaches.

- Some actors did not buy into the Commission’s work, including some within the municipality’s administration. This meant continual framing and re-framing of the problem and the solutions were needed to keep those in positions of power engaged.

Implications for the UK

Local authorities in Sweden are less reliant on central government for funding than those in the UK, and the higher rate of income tax frees up more public funding for investment and experimentation with policy initiatives. Nevertheless, this case study gives UK local authorities some valuable knowledge and insight when planning for and coordinating their own joined-up work across sectors.

UK councils may benefit from building knowledge and capacity for economic evaluations. Assessing the costs and savings from policy interventions is important for understanding their impact on health, enabling costs and savings to be redistributed across the system, and making the case for long-term investment in social policies.

Complex policy interventions, such as the Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö, are inherently difficult to evaluate. New methods for assessing the impact of policies on health and health inequalities will support central and local government and the wider public health community to measure the complex effects of interventions more accurately and comprehensively.

2. Improving air quality in Paris

Summary

To tackle air pollution in the city, the Mayor of Paris provided strong city-level leadership, leading to a diverse range of policies and actions that radically altered the travel behaviour of residents and businesses, including a low emission zone in the city centre.

Timeline

Context

At the start of the century, diesel- and petrol-powered vehicles were the main source of air pollution in Paris, contributing to high levels of air pollution and a range of subsequent health harms.

In 2001, the newly elected Mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, proposed to reduce vehicle traffic within the city to reduce pollution and improve residents’ quality of life.

Delanoë extended and reinforced these ambitions in 2007 through the Paris climate action plan, which included an objective to reduce transport emissions in the city by 60% between 2001 and 2020. The plan included the creation of 700km of cycle routes, subsidised bike and electric moped purchases, a new bike rental scheme called Velib’, an electric car rental scheme called Autolib’ and incentives for citizens and businesses to dispose of their old cars.

The intervention

In 2009, a new national environment law paved the way for a low emission zone scheme in France. The Parisian authorities explored the feasibility of such a scheme but rejected it on several social and economic grounds. However, in 2012 the refreshed Paris climate and energy action plan recognised more ambitious measures would be needed to achieve the 60% reduction in transport emissions by 2020. The updated plan proposed a range of new measures, including lower speed limits, making it easier to walk and cycle, and introducing a low emission zone to restrict the most polluting vehicles from the city.

When the new mayor, Anne Hidalgo, took office in 2014, she announced her intention to implement the low emission zone and to ban all diesel vehicles from the city centre by 2020. After extensive consultation with the French government, businesses and citizens, the mayor’s Air pollution control plan passed into law in 2015 and Paris became the first low emission zone in France. All vehicles must now display a ‘Crit’Air’ windscreen sticker to indicate the vehicle’s level of pollution, and the most-polluting vehicles have restricted access to the city centre.

Evaluation

The main air pollution target of the 2012 Paris climate and energy action plan was to reduce traffic-related emissions by 60% between 2012 and 2020. A monitoring committee oversees progress against the plan’s targets, and the city authorities regularly assess pollution levels, greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption across Paris. This monitoring and evaluation suggests the policies are having a positive impact – for example:

- By 2014, average levels of nitrogen oxides and particulates had fallen by 50%, suggesting the city was on track to meet its target.

- Active travel has risen and car use has decreased. For example, by 2009 cycle journeys had doubled and annual metro journeys had risen by 16%. A new tramline was linked to a 50% reduction in private car use on that route, and across the city centre car traffic has fallen substantially.

- The adoption of similar schemes across France has boosted the French auto manufacturing industry, with Renault selling the largest number of electric vehicles in Europe, ahead of Nissan and Smart.

However, air pollution remains a problem. As recently as June 2017, Paris had to implement its emergency pollution control plans when air pollution exceeded the threshold of 50mcg of particles per cubic metre of air.

Lessons learned

What worked well

Long-term, high-level political leadership and the ability to influence a wide range of stakeholders enabled the Parisian authorities to plan and implement an ambitious range of environmental measures over many years.

What worked less well

While Mayor Hidalgo’s measures have generally been supported by the Parisian people, as the restrictions increase the authorities may need to engage more with citizens and other stakeholders to ensure their continued support. For example, Mayor Hidalgo said she has not tried to ‘sell’ the changes to Parisians, but rather has sought to demonstrate their impact. Commentators have suggested this approach has led to the media remaining ambivalent about Hidalgo’s pollution measures, rather than offering active support.

Enforcement of the low emission zone was under-resourced and only a few fines were handed out in 2017. This may have undermined the scheme. However, since 2018, 2,000 staff members have become responsible for enforcing the zone, which may enhance compliance and drive further improvements in air quality.

Implications for the UK

Success in Paris can be attributed to a mix of carrot-and-stick policies. For example, improved conditions for walking and cycling, better public transport, financial incentives and greater access to electric vehicles all incentivised Parisians to travel sustainably, while increasingly stringent vehicle restrictions discouraged many Parisians from using their cars.

Similarly, carrot-and-stick policies to tackle pollution have been proposed or implemented in the UK, including a diesel scrappage scheme, fiscal policies to disincentivise new purchases of diesel cars, and vehicle charges in the most polluted cities.,

As in France, promoting sustainable travel in the UK may have wider social and economic benefits, such as boosting jobs in the green technology industries.

As vehicle-related pollution fell in Paris, wood burning became a more prominent source of emissions. To mitigate this in the UK, the government could grant powers to localities to ban wood and coal burning in areas with poor air quality and put tougher controls on the sale of wood-burning stoves, with only low-emission versions allowed. The Mayor of London has already called for this action.

3. Tackling social exclusion in South Australia

Summary

South Australia’s Social Inclusion Initiative was a government-wide, whole-system initiative designed to tackle high levels of socio-economic inequalities, increasing rates of chronic disease and disability, and the substantially poorer health of its indigenous population.

Timeline

|

Year |

Event |

|

2000 |

Mike Rann, leader of the opposition in South Australia, commits to tackling social issues in his address to the Australian Labor Party State Platform Convention. |

|

2002 |

New Labor government is elected in South Australia, headed by Mike Rann. |

|

2002 |

The South Australian Social Inclusion Initiative is established, with the creation of the Social Inclusion Board. |

|

2007 |

New Labor government is elected at the federal level in Australia, with Prime Minister Rudd. |

|

2007 |

Australian federal government adopts a Social Inclusion Framework. |

|

2011 |

New Labor government is elected in South Australia, led by Premier Jay Weatherill. |

|

2011 |

New Labor government of South Australia disbands the Social Inclusion Unit and mainstreams its activities. |

Context

South Australia has a population of 1.64 million, of which around 1.7% is Aboriginal. Historically, the state has lagged behind most of Australia’s other states and territories on a range of economic indicators. Its population tends to be older and poorer, with the highest rates of unemployment and lowest incomes in the country, as well as poorer health and wider health inequalities than the national average – especially among its indigenous population.

The intervention

In 2000, there were growing concerns around social justice in South Australia, due to a rise in high-profile problems such as homelessness, drug use, poverty and widening inequalities. In response, Mike Rann, then leader of the opposition, committed to make a ‘change for the better’ if elected, by establishing the South Australian Social Inclusion Initiative (SII) modelled on the UK’s Social Exclusion Unit. Rann’s party did come to power in 2002 and set up the SII to facilitate a government-wide approach to social inclusion and exclusion.

The SII aimed to provide the South Australian government with innovative ways to address complex social issues and develop joined-up, cross-government social inclusion policies and services. It was led by the independent Social Inclusion Board, which sat outside the government’s departmental system and reported directly to the head of government (the Premier). For each priority area, an inter-ministerial committee was established to monitor progress, solve problems and maintain momentum. All integrated policies were presented to and approved by the Cabinet and funded by the Treasury.

The board initially focused on the priority areas of drug misuse, homelessness and school retention, later looking at Aboriginal health and wellbeing, youth offending, mental health, and disability. These areas received almost AU$80m in new funding during the first five years.

One successful activity was the Innovative Community Action Network (ICAN), which worked to improve school retention by developing innovative, accredited learning opportunities in non-traditional out-of-school settings. Another was the government’s Common Ground programme, which invested in new housing developments for homeless people, providing affordable, long-term accommodation and on-site support services, working alongside not-for-profit partners.

At a state level, the South Australia strategic plan included specific cross-departmental social inclusion targets in an effort to mainstream social inclusion and sustain progress when specific SII funding ceased.

Evaluation

Although the SII reportedly incorporated a robust monitoring process, no official reports or formal evaluations have been published. However, some of the SII’s individual programmes were written up or presented as conference papers and the WHO’s Social Exclusion Knowledge Network commissioned a case study of the SII process.

Cross-sector working

The SII served as a catalyst for change, bringing government departments together to remove barriers to intersectoral working. This was partly achieved by encouraging a culture of teamwork across agencies, which helped to break down siloed thinking. The SII also helped build consensus among the various stakeholders on the importance of social inclusion, in an attempt to sustain progress when specific SII funding ceased.

Determinants of health

The SII was credited with raising the profile of the wider determinants of health., Some of its programmes demonstrated impressive outcomes and were adopted elsewhere in the country or mainstreamed. For example, ICAN and related programmes were associated with an increase in school retention from 67% in 1999 to 86% in 2011. Homelessness programmes were linked to a 5% decline in homelessness between 2001 and 2006, bucking the national trend.

Politics

South Australia’s success prompted the 2007 incoming federal government to develop a social inclusion strategy for Australia as a whole. The federal government subsequently established the national Social Inclusion Unit to coordinate a government-wide approach to social inclusion through research and analysis, and set up the Australian Social Inclusion Board.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- There was high-level political commitment in South Australia’s state government, complemented by high-profile champions and leaders, in the form of the chair of the independent board and associated board members, who were respected figures and experts in the area.

- The Premier delegated formal power and authority to the Social Inclusion Board. This enabled the board to intervene across the system to achieve change.

- The involvement of the Treasury ensured that the SII programmes were adequately resourced.

- When SII programmes were developed, a bottom-up approach to community engagement ensured that the programmes addressed issues of importance to the communities and developed solutions grounded in reality.

- The inclusion of specific social inclusion targets in the South Australia strategic plan translated into performance agreements for chief executives of government departments.

What worked less well

- Despite efforts to sell the programme across government, some departments viewed the SII as ‘additional’ work and were unwilling or unable to support it. Similarly, some agencies struggled to fund SII activities through their existing budgets. The Social Inclusion Board and its members could have paid greater attention to building capacity and knowledge on how best to deliver intersectoral work.

- The traditional annual budget cycle hampered departments’ abilities to make long-term plans. This limited the extent to which departments could promote and sustain joined-up working across government.

- Despite providing increased funding for social policies, the Rann government’s SII was criticised for its coercive stance, which focused on ‘assertively’ addressing problem behaviour in specific individuals and groups, as opposed to the systemic determinants of their problems. A related criticism was that it failed to widen its focus to encourage broader cultural change, in order to address the beliefs, attitudes and actions of those doing the excluding.,

- Despite the improvements, the gap between South Australia’s average levels of inequality and the national levels had not changed by the time Rann left office. Some characterised this as a failure of the SII to tackle economic disadvantage, although the Rann government considered wealth redistribution to be the federal government’s remit.

Implications for the UK

Reducing inequalities is a priority in the UK and this case study provides useful lessons for UK actors concerned with implementing joined-up, government-wide approaches to working with socially excluded individuals – for example:

- High-level political leadership, as well as delegated power and authority, is needed to drive a government-wide approach.

- High-level champions can be powerful advocates for change.

- Bottom-up community engagement is essential for identifying problems and their solutions.

- A mechanism for resourcing new programmes is critical to ensuring partner organisations have the capacity to work differently.

- Adopting measurable targets helps embed accountability across government and facilitate a long-term focus.

4. Coordinating US action on prisoner reoffending

Summary

The US government developed the Federal Interagency Re-entry Council to tackle high rates of reoffending among prisoners, which has complex health implications for prisoners and their families and communities. The Council facilitated cross-government collaboration to improve prisoners’ transition to the community and tackle the complex causes of reoffending.

Timeline

Context

As part of the ‘war on drugs’ in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Reagan administration introduced sentencing laws that led to rapid increases in offender sentencing and reoffending rates. This was accompanied by a lack of consensus on what action was needed to address the problem within the criminal justice community.

Today, the US has the highest levels of imprisonment in the world, with a rate of 655 prisoners per 100,000 people in 2016. Being a prisoner or ex-prisoner is linked to poor health outcomes and restricted access to important determinants of health, such as employment, education and housing. These disadvantages also have knock-on effects on prisoners’ families and communities.

The intervention

Under the leadership of the Attorney General during the Clinton administration, the Department of Justice hosted a series of expert roundtables, with accompanying papers, to explore how to address rising prisoner numbers. Drawing on lessons from drug offender programmes, one proposal called on actors to build cross-sector relationships to create a comprehensive system of support for prisoners as they were released from prison, spanning housing, employment and other sectors.

As the issue was debated and explored within the criminal justice community, it gained mainstream attention and widespread public and political support when President Bush committed to an initiative to support prisoners in their transition into the community (termed ‘re-entry’) in his 2004 State of the Union address. In 2007, with bipartisan support, the Bush administration then passed the Second Chance Act, which expanded support for people leaving prison.

Building on the Second Chance Act, in 2011 the Obama administration established the Federal Interagency Re-entry Council, to develop effective re-entry policy and coordinate cross-sector action. The Federal Council’s goals were to make communities safer by reducing reoffending, to help those returning from prison to become productive citizens, and to make financial savings by lowering the direct and wider societal costs of imprisonment.

The Federal Council was chaired by the Attorney General and comprised political leaders and civil servants from each government department. This structure was designed to foster cross-government coordination and sustain action spanning political administrations.

Working towards its goals, the Federal Council and its members developed policies and supported work in a range of sectors, including employment, education, health care and housing. For example, it facilitated the ‘Ban the Box’ policy, which removed the requirement for job applicants to disclose prior criminal convictions at the initial stage of applying for federal jobs. Today, for most federal jobs, criminal history checks take place after a conditional job offer has been made. This has removed an important barrier to work for ex-offenders.

To support ex-prisoners to access stable housing, the Federal Council helped dispel common myths about ex-prisoners’ eligibility for public housing. It clarified the complex laws on this issue and produced a one-page guidance document, explaining that exclusion from public housing applies only to one specific type of conviction.

Evaluation

In 2016, the White House and the Department of Justice published The Federal Interagency Reentry Council: a record of progress and a roadmap for the future. This document reported the key successes of the Federal Council’s first five years and recommended future actions. Successes detailed in the report included:

- Removing barriers to employment for people with criminal records, such as initiating ‘Ban the Box’ (which delayed criminal history checks for federal job applicants), facilitating a new grant-giving scheme to help prisoners become ready for employment, and expanding a micro-loan scheme for businesses with a staff member on probation or parole.

- Expanding access to education, including a pilot programme giving prisoners grants to pursue post-secondary education.

- Reducing barriers to housing by clarifying the rules on access to public housing for people with criminal records.

The US prison population began a steady decline from a peak of 755 per 100,000 people in 2008 (when the Second Chance Act was introduced) to 655 per 100,000 in 2016. The investment and programmes that followed the act, including the work of the Federal Council, are likely to have contributed to this decline.

In recognition of its success, the government expanded membership of the Federal Council from seven to 20 departments. In 2014, the Government Accountability Office identified the Federal Council as one of four model interagency collaborations. This set a positive example for many states and localities and several started similar councils.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- Many years of cross-sector work on reoffending created a community of interest that helped develop consensus-based solutions and carry out relevant research and pilot programmes. This created a favourable environment for the eventual establishment of the Federal Council.

- Re-entry policy actors used evidence-based arguments to reframe the problem of reoffending from one of a perceived threat to public safety that could not be solved to one of opportunity. This gained support from a wide variety of actors with different interests – a factor that was critical in driving and sustaining change.

- The Second Chance Act provided a legal mandate and resources that galvanised interest and action on prison reform and re-entry policy across all sectors. The legal duty to remove barriers to prisoner re-entry created a climate in which the Federal Council could be established and flourish.

- The financial crisis and associated budget crises across local and national government in the late 2000s created a policy window to establish the Federal Council as a way to address the costs of reoffending.

- Although the Federal Council did not have any dedicated funding, it was able to draw successfully on other resources, such as members, champions from business and ex-prisoners to help further its objectives.

- The Federal Council’s governance structure, with a Cabinet-level council and a complementary civil-servant tier, maximised cross-sector coordination, minimised duplication, enhanced the use of evidence-based practices, and ensured sustained action.

What worked less well

Despite the Federal Council’s significant achievements, the US continues to have the highest levels of incarceration in the world and there continue to be barriers to re-entry. For example:

- Coordinating joined-up efforts and actions across agencies to support prisoners’ re-entry is an ongoing challenge.

- Some still perceive re-entry as a threat to society. The Federal Council has been working to present it, instead, as an opportunity to help people to get more out of their lives, stay out of prison and save taxpayers’ funding.

- Because of the complexity of the re-entry agenda, definitive evidence of impact can be difficult to achieve – particularly in an environment with multiple programmes and funding streams. This can be used as an excuse for inaction.

Implications for the UK

Reducing reoffending and improving rehabilitation services are priorities for the government. In 2019, the UK imprisonment rate was 138 per 100,000 people – the highest in Western Europe and second in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) incarceration league table after the US. Record prisoner numbers in the UK have affected safety, decency, security and order in prisons and contributed to overcrowding. Rehabilitation services and initiatives are stretched and fragmented, and failing to deliver effective, joined-up support.

This case study shows how a cross-departmental government committee can coordinate and promote cross-sectoral action to support people as they leave prison and create the conditions for ex-prisoners to integrate back into society. The US experience also offers some useful practical solutions, such as altering employment practices and offering education and training opportunities to people in prison.

5. Increasing access to healthy foods in Pennsylvania

Summary

An initiative to increase the number of supermarkets in deprived communities boosted local employment and business, but poor monitoring made it hard to measure impacts on the dietary health of the local population.

Timeline

Context

In 2018, Pennsylvania had a population of around 13 million and was the ninth most densely populated US state. While the population’s average income is slightly above the US average, in 2018 around 13% of people were living in poverty and one in three over-16s was unemployed.

The state has high levels of diet-related poor health. Obesity is rising and in 2017 around a third of Pennsylvania’s adults were obese. In 2016, only 15% of adults were eating five or more servings of fruit or vegetables a day, and a significant proportion of people were inactive, with 28% of adults reporting no physical activity in the past month in 2017.

Philadelphia is the largest city in Pennsylvania. Since the 1960s, complex social, economic and public policy factors had left many neighbourhoods without supermarkets or other businesses, known as the ‘grocery gap’. This gap was underpinned by a range of factors, including an exodus of white, middle-class families to homes in the suburbs and a loss of businesses as a result of more business-friendly zoning in other areas.

Philadelphia’s supermarket shortage reduced access to healthy, fresh food and increased health inequalities for those left behind. One example was Progress Plaza, Philadelphia’s oldest African-American-owned neighbourhood development, which served as a vital part of the African-American community for three decades. When the Plaza’s supermarket closed in 1998, the Plaza fell into disrepair, access to healthy foods declined and diet-related conditions such as obesity increased.

The intervention

The Food Trust is a Philadelphia-based NGO that aims to increase access to healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables in underserved neighbourhoods. In 2001, the organisation published a report entitled Food for every child: the need for more supermarkets in Philadelphia, exposing the lack of access to healthy food in Philadelphia and its negative health impacts. The report included maps that starkly revealed neighbourhoods affected by multiple adverse factors, including no or few supermarkets, low incomes and high rates of diet-related deaths. This graphic illustration of the problem communicated powerfully to policymakers that food access was an urgent and expensive public health concern as well as an economic and social justice issue.

Philadelphia City Council welcomed the report and asked The Food Trust to convene a taskforce to develop ways of increasing supermarkets in underserved areas across Pennsylvania, with the goal of increasing access to healthy food and improving diet-related health. The taskforce brought together stakeholders from the public sector, businesses and civil society to discuss the action needed, and published 10 recommendations in a report in 2004.

In response to these recommendations, later that year the state governor launched the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative (PFFFI) to attract supermarkets and grocery stores to underserved urban and rural communities. The PFFFI’s objectives were to:

- reduce the high incidence of diet-related diseases by providing healthy food

- stimulate investment of private capital in low-income communities

- remove financial and other barriers for supermarkets to operate in deprived communities

- create living wage jobs

- prepare and retain a qualified workforce.

The PFFFI was a state-wide financing programme, operated as a public-private partnership between Pennsylvania’s state government, The Food Trust, a community development funder called the Reinvestment Fund, and the Urban Affairs Coalition, an organisation that works with local communities to drive change.

Each organisation played a unique role in implementing the programme. The Food Trust and the Reinvestment Fund promoted the initiative across the state and identified potential markets, assessing where the need was greatest and how the PFFFI’s resources could best be used. The Pennsylvania government provided US$30m in seed funding over the first three years and the Reinvestment Fund raised a further US$117m from banks and philanthropic foundations. The Reinvestment Fund used the funds to offer grants and loans to supermarket operators locating in underserved communities. The Urban Affairs Coalition worked with supermarket developers to increase opportunities for local people to be involved with the construction, operation and ownership of funded stores.

Funding for the PFFFI ceased in 2009 following the economic crisis. However, there was ongoing support for the initiative at state and federal levels, and the state’s House Appropriations Committee recommended the programme be revisited when the economic climate improved.

Evaluation

No formal evaluation process was built into the design of the PFFFI but several small studies were undertaken to assess different impacts of the programme across different parts of Pennsylvania.

Between 2004 and 2010 the programme achieved several positive outcomes – for example:

- More than 5,000 jobs were created or retained, and revenues of neighbourhood stores in deprived communities increased. The Reinvestment Fund estimated that every US$1 invested generated US$1.5 in benefits to the community.

- More than 400,000 residents gained greater access to healthy food.

- The initiative inspired similar projects in New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Louisiana and Colorado, as well as a national programme, launched in 2010, to improve access to healthy food through providing grants and loans, using joint funds from the departments of agriculture, treasury, health and human resources.

- The programme dispelled negative myths about deprived communities, including that businesses could not be profitable and crime would be higher in deprived communities.

No studies identified any impact on diet-related or health outcomes. One study found that proximity to a supermarket was not related to weight or dietary quality among residents from urban food desert neighbourhoods. Another reported no significant impact on body mass index (BMI) or daily fruit and vegetable consumption after six months of a new supermarket opening, although the follow-up period may have been too short to detect changes.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- The Food Trust provided powerful institutional leadership, partly owing to its strong links to the community in Philadelphia, which gave it credibility.

- The Food Trust’s high-profile report Food for every child provided high quality evidence of the problem and helped create a policy window for change.

- Elected State Representative Dwight Evans used his influential position to champion the issue across the state and secure support for action. High levels of public support further increased political engagement.

- Bringing together diverse stakeholders from the health, development and economic sectors facilitated shared understanding of the issues and built consensus on the solutions.

- The initiative maintained its focus on the single issue of the grocery gap, which prevented the message from being diluted.

- The programme’s flexible design, combining financial grants and loans, enabled support to be tailored to the different actors and contexts and helped the programme strike an appropriate balance between risks and responsibilities.

What worked less well

- There was no formal, comprehensive evaluation built into the PFFFI. This substantially limited the quality of subsequent attempts to measure its impacts. For example, because no baseline data about diet or BMI were collected, it was difficult to fully assess the programme’s success.

- Follow-up studies found no evidence that the PFFFI increased healthy food consumption or improved diet-related health problems. This could be due to the short timescales of most studies, the challenges of studying the complex causes of obesity and complex impacts of the intervention, or a lack of accurate data. Meanwhile, some evaluations measured only interim economic indicators, such as numbers of new supermarkets or jobs created, which gave no information about health impacts. This absence of evidence could deter policymakers from improving food access to tackle health problems in the future.

- Despite the wide variety of private partners involved in the PFFFI, funding ceased in 2009 once the state could no longer provide financial support following the financial crisis. This raises questions about the long-term sustainability of public-private partnerships.

Implications for the UK

The UK faces similar challenges, including food deserts in deprived neighbourhoods and the decline of the high street, characterised by shop closures and local job losses. This case study provides some important lessons on how different actors from public health, development and economic sectors can come together to develop joint solutions to these problems.

6. Targeting health inequalities through government reform in Norway

Summary

To tackle wide health inequalities, the Norwegian government introduced a comprehensive Public Health Act to embed a health in all policies approach across all levels of government and ensure responsibility for health inequality across sectors.

Timeline

Context

Norway has historically been described as a social democratic welfare state, with its emphasis on solidarity, universalism, equality and redistribution of resources through a progressive tax system. The country has become increasingly wealthy over the past 30 years thanks to its growing oil economy, yet is home to significant health inequalities. For example, people with the lowest education levels had significantly shorter life expectancies and higher rates of physical and mental illness than those who had been to university.

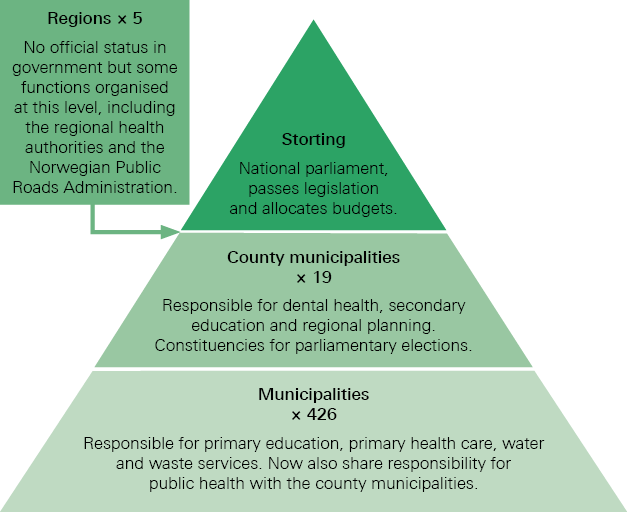

Norway has three democratically elected levels of government:

- the Storting (national parliament)

- county municipalities

- local municipalities.

All three have public health responsibilities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Norway’s levels of government and their public health responsibilities

The intervention

Although past Norwegian governments have sought to reduce health inequalities, their policies traditionally focused on lifestyle interventions targeting disadvantaged groups rather than addressing the social determinants of health more broadly. In 2005, a centre-left government won power on the promise to fight poverty and work for a more equitable society in terms of income distribution, education and health. In 2007, it set out an ambitious 10-year strategy to reduce the health gradient, taking a cross-ministerial approach covering childhood, adolescence and education, work, income, health services, health behaviours and social inclusion.

Following a cabinet reshuffle in 2008, the new health minister set in train a series of reforms, known as the ‘coordination reforms’, to improve health care and give the health sector a greater role in preventing and reducing health inequalities. However, these ambitions were met with resistance from the public health community, which was concerned that increasing the health sector’s role in prevention would undo progress that counties and local municipalities had already made in making health a multi-sector responsibility. They argued that the government should introduce a comprehensive, cross-sectoral Public Health Act that applied to all levels of government.

In 2012, Norway’s Public Health Act came into force with the aim of improving health and reducing health inequalities. The Act applied to all levels of government and was based on five fundamental principles.

- Health equity: fairly distributing societal resources is good public health policy.

- Health in all policies: joined-up governance and intersectoral working are key to reducing health inequalities.

- Sustainable development: public health work needs to take a long-term perspective to meet people’s needs today while not compromising future generations.

- Precautionary principle: if an action or policy is suspected of being harmful, the absence of evidence of harm should not justify postponing action to prevent such harm.

- Participation: involving all relevant stakeholders, including civil society, is key to good public health development.

Locally, the act provided a legal mandate for municipalities to deliver public health across sectors. For example, municipalities were required to include public health measures in their local strategic plans across a specified list of social determinants, including housing, education, employment, income, and physical and social environments.

At a county level, the act required counties to identify their public health challenges and use these as a basis for their regional planning strategies and embedding health across departments. Nationally, all government departments were required to adopt a health in all policies approach, and the Ministry of Health and Care Services became responsible for supporting municipalities with local health intelligence and guidance.

Evaluation

- At national level, the Public Health Act is seen as a useful tool for securing health in all policies because it places a legal duty on all ministries. However, there is limited evidence that ministries have changed their policymaking approach in practice.

- County-level authorities struggled to embed health in all policies. This was partly due to difficulty shifting the focus from lifestyle issues to the social determinants of health. This was exacerbated by the Ministry of Health and Care Services continuing to launch lifestyle-focused public health campaigns.

- At local level, many believe the act has raised the prominence of public health and increased action on the social determinants of health in local government. In 2014, almost half the country’s municipalities addressed living conditions as part of their health promotion activities, compared with 6% of municipalities before the act.

- More municipalities have comprehensively assessed their population’s health needs since the act. In 2014, 38% of localities had completed a comprehensive local needs assessment, compared with 18% before the act.

- A third of municipal managers reported that public health investment has increased as a result of the act, although spending has mainly been on organisational structures and processes, such as creating new job roles, rather than delivering more health promotion measures.

- More municipalities now employ a public health coordinator to facilitate cross-department collaboration. This has worked best in places where the post is full time and the coordinator is embedded in the local government. However, many areas have created part-time coordinator roles within the health sector, which has limited coordinators’ ability to lead change.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- The Ministry of Health and Care Services framed the Public Health Act and the health in all policies approach as tools to support other sectors to meet their objectives, which helped secure cross-sector buy-in.

- Giving local areas the freedom to set their own public health priorities, rather than having them mandated by the state, achieved political buy-in across parties.

- Making municipalities responsible for health in all policies nurtured a culture change among local politicians that has started to filter up to county and national levels as they move up in their careers.

What worked less well

- Legislation alone was insufficient to drive and maintain a cross-sectoral approach to public health. Continued efforts are needed to influence politicians and practitioners to adopt a health in all policies approach.

- Local areas lacked dedicated senior capacity to drive health in all policies across the municipality and in partnership with neighbouring areas. This limited the extent to which the approach was implemented.

- Without additional, dedicated funding from national government, local action was largely limited to deploying a coordinator post and supporting joint ways of working, rather than implementing new initiatives.

- Beyond health protection and environmental health concerns, the act did not give powers to curb private-sector actions that undermine health, so it could not address the impact of commercial determinants of health on the inequalities gradient.

Implications for the UK

A Public Health Act could articulate clear responsibilities at each level of government and may support a health in all policies approach nationwide. Long-term partnerships with representative bodies such as the Local Government Association would be vital to build capacity and secure buy-in from politicians, practitioners and the public.

Small or rural areas may lack the capacity to tackle health inequalities at a local level. However, the closer integration of health and local government across larger geographical footprints, and the emergence of city regions, may create the scale and pooled resources needed to improve conditions for both rural and urban communities.

The case study highlights the importance of public health leadership at a senior level. In the UK, directors of public health are not always embedded at executive level, and this may limit their influence. Meanwhile, there are some interesting UK examples where the public health function is distributed across the council. It would be valuable to investigate whether this has led to better coordination of public health and a health in all policies approach compared with those councils where public health is a discrete function.

7. Tackling obesity in Canada through urban design

Summary

To stem Canada’s rising obesity levels, the Urban Public Health Network built a coalition of organisations, including planners, engineers, health charities and local government, to develop and share ways of embedding health in urban and transport policy and planning.

Timeline

|

Year |

Event |

|

2008 |

Canada’s Urban Public Health Network (UPHN) establishes a Healthy Built Environment working group for its members. |

|

2008 |

UPHN establishes a loose, cross-disciplinary coalition of organisations interested in healthy built environments. |

|

2009 |

Coalition members successfully bid for Coalitions Linking Action and Science for Prevention (CLASP) funding to formalise the coalition, and the Healthy Canada by Design coalition is formalised. |

|

2009–12 |

Delivery of Healthy Canada by Design phase one projects. |

|

2010–12 |

Process and outcome evaluations of Healthy Canada by Design phase one projects. |

|

2012–14 |

A second phase of Healthy Canada by Design projects is funded. |

Context

In 2008, in response to rising obesity in Canada, the Urban Public Health Network (UPHN) established a Healthy Built Environment working group to find ways to make health a central consideration in urban and transport planning, including to promote walking and cycling.

The working group believed it would need to convince the planning and engineering community of the benefits of a healthier built environment, and was concerned that public health professionals lacked the knowledge to accomplish this. However, Canada’s planning and engineering community was already keen to address urban sprawl, reduce congestion and promote cleaner air. In addition, improving the urban realm was becoming a public and political priority across the country, as people started to realise congestion in towns and cities was damaging economic growth, and younger voters began shunning the car and demanding safer streets and better walking and cycling routes.

This groundswell of diverse interests with a shared goal created a fertile environment in which to act.

The intervention

In 2008, the UPHN brought together a cross-disciplinary coalition of interested parties to explore how their efforts could be better supported and coordinated. The coalition comprised:

- six provincial health authorities that were UPHN members: Peel Region, Toronto, Montreal and three health regions of southern British Columbia

- four national partners: the Heart and Stroke Foundation, the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, the Canadian Institute of Planners, and the Canadian Institute of Transportation Engineers.

For the Canadian Institute of Planners and the Canadian Institute of Transportation Engineers, the value of joining the UPHN coalition was to be able to harness health arguments and the influence of public health professionals to help drive forward changes. A key purpose of the coalition became to upskill public health professionals so they could bring their influence to bear on planning decisions.

The Healthy Canada by Design coalition

In summer 2009, the UPHN coalition secured a Can$2m grant from the Coalitions Linking Action and Science for Prevention (CLASP) programme, and Healthy Canada by Design formally came into being.

The Healthy Canada by Design coalition aimed to develop and disseminate ways of embedding health in urban and transport policy and planning to improve the population’s health. It would do this by:

- improving understanding across sectors of the relationship between the built environment and health, including how policy, programmes and public engagement can be used to develop healthier environments that contribute to preventing illness

- making new, state-of-the-art decision-making tools available to policymakers and practitioners across sectors

- developing a new community of practice that would include the public health community, planning professionals and NGOs, to translate the literature linking the built environment and health into usable, practical tools.

The coalition funded projects in six provinces. For example, in British Columbia three health authorities used the funding to build staff capacity for developing evidence-based healthy planning policies, including:

- teaching staff about how the built environment and health are linked

- supporting staff to use evidence for local policymaking and practice

- creating networking opportunities for public health staff and urban planners.

The partners with national reach took on an overarching knowledge transfer and exchange role, which involved disseminating learning through webinars, reports, conference presentations and workshops, and meetings with key strategic stakeholders.

Evaluation

Each of the six projects and the overall Healthy Canada by Design project were evaluated through process and outcome evaluations. The evaluations gathered data from public health specialists and professionals from other sectors using a variety of methods, including surveys, focus groups and interviews. The findings included:

- The CLASP grant made urban planning a more strategic priority for coalition members. The funding led to in-kind resources being allocated by each of the national partners and each of the six sites, amounting to Can$1.4m additional investment.

- Health authorities built new relationships with other health authorities and other sectors, particularly local planning departments. This facilitated information sharing and created opportunities to influence decisions about the built environment.

- Public health staff became more skilled at working with partners outside of public health to improve the built environment. In 2010, 62% of public health survey respondents felt they had increased their skills. In 2011, this rose to 80%. In turn, urban planners became more aware of the health impacts of the built environment and said they would consider health more in local policies and plans.

- In British Columbia, health was increasingly included in urban planning policies and strategies. For example, the 2011 Metro Vancouver regional growth strategy committed to develop healthy communities with access to services and amenities. In the city of North Vancouver, health authority staff were embedded in the planning team to develop the district’s official community plan and other strategic planning documents.

Lessons learned

What worked well

- Professionals working in public health, planning and transport embraced the opportunity to work together and learn from each other because they shared similar goals.

- Bringing experienced planners into public health departments upskilled public health staff and increased their capacity to work with planning colleagues and influence the planning process.

- Framing health conditions such as obesity as a planning issue, rather than a health issue, and developing medical professionals’ abilities to advocate in planning terms, contributed to healthier planning decisions.

- External funding helped catalyse the partnerships and supported continuing partnership working, which influenced partner organisations to prioritise and invest in health.

What worked less well

- Healthy Canada by Design was delivered and evaluated over a three-year period. Given the length of the planning process (typically, 5–10 years), and since the health impacts of urban realm improvements can take many years to become evident, this timescale may have been too short to deliver and measure meaningful change.

- Similarly, participants in the evaluation suggested public health departments would need more than three years to fully integrate urban planning into their work programmes. Partners could have invested more in continuity planning to ensure teams were prepared to sustain the integrated approach after funding ceased.

- While commercial developers broadly accepted Healthy Canada by Design at national level, companies objected to some specific proposals in which they felt profit and public health objectives were at odds. Some developers did not engage in the project at all, or used their power to block plans, due to concerns that it would increase costs and reduce profit margins. Stronger political commitment and leadership may have helped planners overcome these challenges in order to create healthy communities.