Acknowledgements

The Health Foundation’s healthy lives strategy has been developed with guidance and advice from an external reference group. Thank you to:

- Jessica Allen, Deputy Director, UCL Institute of Health Equity

- Shirley Cramer, Chief Executive, Royal Society of Public Health

- Christine Hancock, Director, C3 Collaborating for Health

- Paul Lincoln, Chief Executive, the UK Health Forum

- Harry Rutter, Senior Clinical Research Fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- Ollie Smith, former Director of Strategy and Innovation, Guy’s & St Thomas’ Charity.

We would also like to thank everyone who helped us shape our strategy.

The Health Foundation is an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and health care for people in the UK.

In 2017, we will begin implementing a long-term strategy to improve people’s health in the UK.

Our healthy lives strategy

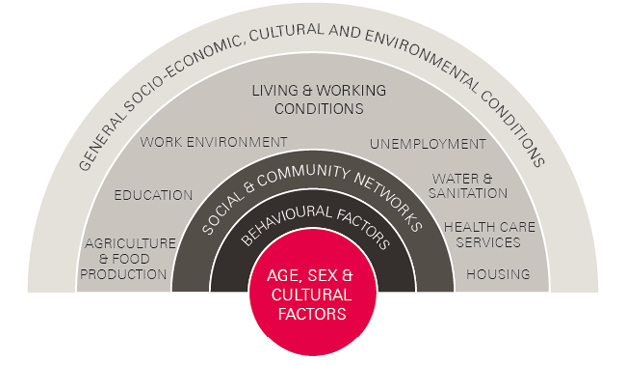

Good health is an asset. It is necessary for a prosperous and flourishing society. The greatest influences on our wellbeing and health are factors such as education and employment, housing, and the extent to which community facilitates healthy habits and social connection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The factors that influence an individual’s health and wellbeing

Access to health care accounts for as little as 10% of a population’s health and wellbeing. While equipping health care systems to provide safe, timely and effective care is as important as ever, this is far from sufficient on its own to improve people’s health in the UK.

During 2017, the Health Foundation will begin to implement a long-term strategy that aims to bring about better health for people in the UK. The aims of the strategy are to:

- change the conversation so the focus is on health as an asset, rather than ill health as a burden

- promote national policies that support everyone’s opportunities for a healthy life

- support local action to address variations in people’s opportunities for a healthy life.

The strategy has been developed through extensive formal and informal engagement with multiple stakeholders. This engagement has highlighted that the impact of our strategy will not rely on simply ‘what’ the Foundation chooses to focus on as much as ‘how’ we approach the challenge. Drawing on the insights gathered so far, we have identified eight themes to guide our strategy to improve people’s health in the UK. Here we outline these themes and why we think they are important.

This document is accompanied by a compendium of resources and case studies that we have found helpful in developing our strategy. Visit: www.health.org.uk/healthy-lives-strategy

How are we implementing our strategy?

“Why treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?”

Michael Marmot

The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World

People’s health is influenced by political, social, economic, environmental and cultural factors. These factors shape the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age. They are affected by the distribution of power, money and resources across society.

Although at lower income levels the health of a population is related to GDP, above a certain threshold this relationship becomes a lot more complex. This tells us that health is not just about wealth. For example, the US has a lower life expectancy at birth than less wealthy countries including France, Sweden, Spain, the UK and Japan., Furthermore, the US spends more on health care than the UK, yet has higher prevalence of conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

The social determinants model is important because it seeks to identify the ‘causes of the causes’ – for example, the inequality in social and economic conditions that may explain a child developing asthma due to poor housing conditions and lack of access to green space, or the psychosocial effects of a low-paid, temporary job on a worker’s risk of experiencing chronic stress and developing cardiovascular disease. These conditions are largely, or completely, outside of an individual’s control.

“Most of the determinants of health have nothing to do with health services and have everything to do with broader public services, the environments in which we live, and people’s opportunities to lead healthy lives.”

Naomi Eisenstadt

Healthier lives: a listening exercise

Unequal distribution of social determinants contributes to disparities in health – for example, in Scotland life expectancy at birth is usually higher in the least deprived council areas compared to the most deprived council areas (as measured by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation).

Work on the social determinants of health has been underway for decades; however, recent publications such as the 2008 WHO Closing the gap in a generation report and the 2010 Marmot Review have contributed to their increasing recognition. In England, over 70% of local authorities are now working towards implementing the Marmot review’s six policy recommendations.

The Health Foundation is adopting a social determinants approach to improving health.

Taking a systems approach

Complexity theory and systems thinking are important frames for considering action for improving health. They consider the numerous interactions between multiple parts of a given situation and the adaptations that arise from these interactions. The idea of finding a modern-day ‘pump handle’ to solve the problem of, for example, obesity is alluring in its simplicity. However, the reality of the current environment and the vectors of modern diseases means that, as one system property changes, the system self-modifies. This is sometimes positive – reinforcing and amplifying health-enhancing habits – but can be negative, making goals harder to reach. Fundamentally, when working in systems ‘the single most important intervention is to understand that there is no single most important intervention’.

“Systems change aims to bring about lasting change by altering underlying structures and supporting mechanisms which make the system operate in a particular way.”

Pennie Foster-Fishman

Taking a systems approach emphasises the importance of looking beyond the tangible intervention and understanding issues including: the wider conditions within which the intervention was developed (eg how problems and the need for change were identified); how ideas and solutions were generated; how motivation was harnessed; and the underlying attitudes and beliefs of those involved in the intervention. Particular focus is needed on:

- the less tangible aspects of an intervention that may influence how it plays out – for example, behaviours and attributes of those leading the initiative, the relationships between the formal agencies and the community or environment

- potentially unexpected consequences of the intervention’s interaction with elements of the wider system – for example, moves to reduce the amount of fat in biscuits and cakes to create products marketed as ‘lower fat’ or ‘better for you’ have in some cases led to increases in the sugar content and no reduction in calories.

The Health Foundation will be applying complexity theory and systems thinking to the design of our work programme.

Seeing health as an asset

Although the health of the UK population has seen improvements in the last 50 years, we nevertheless face a formidable burden of preventable disease. The shortcomings of a system that has focused disproportionately on treating disease when it arises, rather than investing in actions that maintain health over the life course, is becoming more visible. The loss of economic value of a workforce no longer able to participate in employment up until their retirement age is calculable. The loss in social value as a consequence of a population limited in its capacity to contribute to family life and community is inestimable.

A social determinants approach which frames good health in terms of the conditions and attributes that maximise health over the life course offers a fresh perspective on this challenge. This view would define a ‘healthy person’ not as someone free from disease but as someone with the opportunity for meaningful work, secure housing, stable relationships, high self-esteem and healthy habits. Understanding health in these terms would highlight lack of employment opportunity and access to affordable housing as a health problem. Rather than simply improving society’s ability to respond to disease, more emphasis would be placed on actions that promote the conditions for good health.

“The ultimate source of any society’s wealth is its people. Investing in their health is a wise choice in the best of times, and an urgent necessity in the worst of times.”

David Stuckler

The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills

Good health is both of value to the individual and a societal asset necessary to generate social and economic value. When seen as such, health takes a position as an important aspect of social infrastructure – an enabler of the prosperous society governments strive to create. The case for investing for the longer term then becomes apparent – just as the case for long-term investment is accepted when it comes to transport, energy, or telecommunications infrastructure.

The Health Foundation will be building a body of research to explore the evidence of the impact of health on social and economic development.

Working across sectors

Maintaining and improving health cannot be the responsibility of a single sector. While government has a central role in shaping much of the environment that influences people’s choices and opportunities for a healthy life, everyone has a role to play in supporting and promoting health. For example:

- communities depend on individuals being able to play an active role

- employers and businesses need a productive workforce now and in the future

- national government and local authorities want to promote economic and social prosperity.

It is hard to find a sector that doesn’t have a bearing on our health. For example: schools and colleges build our future potential; the arts, culture and sport support our mental and physical wellbeing; unions and others promote work environments that protect our health; the media explain and inform (or misinform).

“Few health threats are local anymore. And few health threats can be managed by the health sector acting alone.”

Dr Margaret Chan

Address to the Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly

More can be done to align the decisions and actions of these stakeholders with the goal of maintaining and improving health. Greater knowledge and understanding of the evidence on the social determinants of health is a necessary first step. However, even where this is understood, there can be disincentives to taking action as the benefits often don’t visibly accrue to the sector making the investment, or within a timeframe to overcome short-term interests.

Building shared goals around improving health across agencies at local level can catalyse effective action. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, whose aim is to build a ‘culture of health’ in the US, has championed a systematic approach to engaging local communities in the factors shaping their health through its County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. The rankings highlight clearly the contributions to health made by factors beyond health care. Making these apparent has been effective in engaging local communities and has mobilised joint action across civil society, statutory agencies and local businesses.

The Health Foundation will be promoting cross-sectoral action at national and local level to improve health.

Using the principles of co-creation

While government policies influence the macro environment, an individual’s health is also shaped by their day-to-day experiences within their local community. There are many examples of community led action to create healthy neighbourhoods but little understanding as to how such initiatives can be replicated elsewhere.

In complex systems, solutions are context specific and cannot necessarily be ‘lifted and shifted’ from one place to another. It is the processes that enable solutions to be co-created that need to be replicated.

Successful community interventions share a number of similar characteristics:

- Engagement is with a community – rather than through a focus on single issues – enabling a holistic understanding of the underlying causes of poor health.

- Priorities for action are set by the community, thereby increasing ownership of proposed changes.

- Solutions are co-created, drawing on assets within the community, meaning they are attuned to local needs and values through open dialogue.

- Positive outcomes build a sense of agency and support further community action.

“Fundamentally [asset-based approaches] ask the question ‘What makes us healthy?’ rather than the deficit-based question ‘What makes us ill?’”

Simon Rippon and Trevor Hopkins

Head, hands and heart: asset-based approaches in health care

Supporting successful community action demands different skills and behaviours to those needed for the planning and delivery of services. It requires a rebalance of power from the state to communities and from professions to the public – those in statutory roles at local level must re-think their roles in terms of community empowerment rather than service provision.

The Health Foundation will build further evidence on community led approaches to change.

Shifting habits and norms

Although people seemingly make their own choices about the factors that influence their health – whether or not they smoke, how much physical activity they do, the nature of their diet – these decisions are heavily influenced by social norms and the range of choices available. Promoting healthy behaviours needs to reflect this.

“…changing behaviours is challenging, as the contexts in which they occur are complex, involving the interaction of people’s individual characteristics, social influences and physical environment – among other things.”

Dr Ildiko Tombor and Professor Susan Michie

Social norms are not static and the factors that shape them are complex. Tighter legislation on tobacco, for example, has led to significant reductions in smoking and changed attitudes towards tobacco consumption. However, the introduction of this legislation would not have been possible without many years spent building public acceptance of the case for greater control. In contrast, the liberalisation of licensing laws in the post-war era has led to normalisation of greater alcohol consumption, making it hard for policy makers to act on public health evidence.

Even when there is a wider shift in societal views, attitudes and expectations may differ within specific communities. For example, expectations of ageing healthily are very low among some socioeconomic groups in the UK and these expectations may be linked with unhealthy behaviours such as very sedentary lifestyles.

The influence of social networks illustrates the limitations of individually focused interventions and highlights the need for systems approaches that influence habits and norms of populations not simply individuals. Behavioural insights studies have shown that most decisions people make are fast, instinctive and automatic, rather than slower, considered and logical. Environments and initiatives that are conducive to healthier, automatic choices are the most sustainable and should be targeted as part of public health efforts.,

The Health Foundation will be exploring the potential of behavioural insights approaches to improving health.

Building the evidence base

Public health research largely sits within or alongside the world of medical research, looking to the same funding streams, employing similar methodologies and publishing in many of the same journals. These approaches to building evidence tend to focus on individual-level action in comparatively straightforward cause-and-effect relationships.

However, securing good health over the life course requires population-level as well as individual-level action. And the steps that need to be taken will be mediated by other factors in the context in which they are implemented. This demands a new approach to measuring and evaluating that reflects the complex and adaptive nature of the challenge and solutions.

“…reshaping public health research, policy and practice to take full account of the central importance of complex systems will be essential to improve health and reduce inequalities globally.”

Harry Rutter

Towards a complex systems model of evidence for public health

In the absence of an agreed alternative to generating public health evidence, there is a bias towards funding interventions to improve health that operate at an individual level over the short term. Common to other fields of research, there is tendency to focus on evaluating the impact of an intervention without fully understanding the context within which it plays out and how that context may amplify or mitigate the desired change.

Taken together, these biases impede the generation of evidence needed to understand the impact of population-level action, how context contributes to outcomes, and how interventions that are shown to make a positive contribution can be translated effectively into other contexts.

Recognition of the importance of a wider set of approaches to generating evidence is gaining traction. Moving towards greater design and evaluation of population-level interventions focused on prevention will be helped by:

- decision makers understanding the limits of evidence generated by randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and the value of alternative approaches to generating evidence

- training public health researchers and supporting them to embrace a wider set of methodologies

- the creation of funding mechanisms to support evidence building in this field.

The Health Foundation will be developing approaches to design and evaluate population-level interventions to improve health.

Mobilising wider resources

The £116.4bn allocated to the Department of Health in 2015/16 and, through them, to the NHS and other agencies is generally described as the ‘health’ budget. However, given that health is determined by wider social factors, all public spending has the potential to influence health. In addition, looking beyond government spending, business and the third sector can also make significant contributions to people’s health.

The value to employers of a healthy population needs to be made explicit both in terms of the importance of good health among existing employees and the health of the future workforce. Michael Grossman’s concept of health capital – described as a ‘stock’ that degrades over time without investment – could be a helpful way of doing this. His model illustrates the greater return on investment for interventions that preserve or replenish health capital in early life compared to those made in later life.

If considered at population level, health capital has the potential to shift attention beyond static measures of health and wellbeing. The rate of depletion of the stock of health capital in a community could provide a predictor of future social and economic prosperity. Such a concept could be a catalyst in engaging local leaders across statutory authorities, local businesses and whole communities to take collective responsibility in planning and acting to protect and grow health capital over the long term.

“…a longer-term perspective on the future benefits of investing in health and its drivers is especially critical. New and creative thinking is needed about sources and flows of funding; the balance over time of preventing conditions versus preventing their progress and complications; and the motivators for cross-sectoral investment in health.”

Dr Louise Marshall and Anita Charlesworth

There are many thousands of voluntary organisations that are health creating – for example, supporting children and families, building communities, or helping people manage crises such as debt or homelessness. There needs to be more explicit recognition of the value they generate and support for their continued contribution.19 Not only because of the benefits of the contribution itself, but because volunteering and giving are also health enhancing.

The Health Foundation will reach beyond statutory organisations to all sectors to encourage them to recognise and act on their role in improving health.

“The shift of the Health Foundation to move from a pure focus on health care to address the broader issues of health is extremely welcomed.”

Derek Yach

Healthier lives: a listening exercise

* ‘Causes of the causes’ refers to the underlying causes of health problems.

† On 31 August 1854 a sudden outbreak of cholera in Soho, London, led anaesthetist John Snow to trace the source of the infection to a single water pump on Broad Street. The pump handle was removed, successfully stalling the spread of infection: www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/broadstreetpump.html.

This is just the start…

In 2017, we are starting to implement our long-term strategy to support everyone’s chance of a healthy life in the UK. We will bring a fresh perspective, independent analysis and the experience we have in making change happen in complex systems. Over the coming years, we will be promoting policies and encouraging local action that can make a real and lasting difference.

Our aims are:

- changing the conversation so the focus is on health as an asset, rather than ill health as a burden

- promoting national policies that support everyone’s opportunities for a healthy life

- supporting local action to address variations in people’s opportunities for a healthy life.

Given the breadth of this challenge we will continue to extend our networks and work in partnerships with others to take this work forward.

Join us on our journey

We welcome comments and feedback on our strategy and proposed approach outlined here.

Please contact healthteaminbox@health.org.uk

References

- Adapted from Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies; 1991.

- McGovern L, Miller G, Hughes-Cromwick P. Health Policy Brief: The relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Affairs. 21 August 2014. Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_123.pdf

- Marmot M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2015.

- World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2005–08. Available from: www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/en

- World Bank data (for GDP per capita (current US$) in 2015. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?year_high_desc=false

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2016. Geneva: WHO; 2016. Available from: www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/Annex_B/en

- Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Smith J. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA. 2006; 295(17): 2037–45. Available from doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2037

- Rose G. Sick Individuals and Sick Populations. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1985; 14(1): 32–8. Available from doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32

- Eisenstadt N, speaking in: The Health Foundation. Healthier lives: a listening exercise. [Video] 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/healthier-lives-listening-exercise

- National Records of Scotland (NRS). Life Expectancy in Scottish Council areas split by deprivation, 2009–13. NRS; 2014. Available from: www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//statistics/life-expectancy-scottish-areas/scottish-council-areas/le-council-area-deprivation-2009-13.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO) Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Available from: www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en

- Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review; 2010. Available from: www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

- University College London (UCL). Impact of the Marmot Review: national and local policies to redress social inequalities in health. London: UCL; 2014. Available from: www.ucl.ac.uk/impact/case-study-repository/marmot-review

- Rutter, H. The single most important intervention to tackle obesity… International Journal of Public Health. 2010;57(4): 657–8: Available from doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0385-6

- Foster-Fishman PF. How to create systems change. Lansing: Michigan Developmental Disabilities Council; 2002.

- Stuckler D, Basu S. The Body Economic: Eight experiments in economic recovery, from Ireland to Greece. London: Penguin; 2014.

- Chan M. WHO Director-General’s Address to the Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly. 23 May 2016.

- Rippon S, Hopkins T. Head, hands and heart: asset-based approaches in health care. London: the Health Foundation; 2015. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/HeadHandsAndHeartAssetBasedApproachesInHealthCare.pdf

- Collaborate/New Local Government Network (NLGN). Get Well Soon: Reimagining Place-Based Health – The Place-Based Health Commission Report. London: NLGN; 2016. Available from: www.nlgn.org.uk/public/wp-content/uploads/Get-Well-Soon_FINAL.pdf

- Tombor I, Michie S. Interventions and policies to change behaviour: what is the best approach? A healthier life for all: The case for cross-government action. APPHG and the Health Foundation; 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/AHealthierLifeForAll.pdf

- Anderson P, Baumberg B. Alcohol in Europe: A public health perspective – A report for the European Commission. London: Institute of Alcohol Studies; 2006. Available from: www.ias.org.uk/uploads/alcohol_europe.pdf

- Sarkisian CA, Prohask, TR, Wong MD, et al. The relationship between expectations for aging and physical activity among older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 20(10): 911–15: Available from doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0204.x

- Kahneman D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin; 2011.

- Marteau T, et al. Changing Human Behavior to Prevent Disease: The Importance of Targeting Automatic Processes. Science. 2012; 337: 1492–5 Available from doi: 10.1126/science.1226918

- Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. PLOS Medicine. 2016; 13(5): e1001990: Available from doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990

- Rutter H, Glonti K. Towards a new model of evidence for public health. The Lancet. 2016; 388: S7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32243-7

- The Academy of Medical Sciences. Improving the health of the public by 2040. London; The Academy of Medical Sciences; 2016. Available from: www.acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/41399-5807581429f81.pdf

- Nuffield Trust, the Health Foundation, The King’s Fund. The Spending Review: what does it mean for health and social care. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/spending-review-what-does-it-mean-health-and-social-care

- Grossman M. On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health. The Journal of Political Economy. 1972; 80(2): 223–55.

- Marshall L, Charlesworth A. The economic case for preventing ill health. A healthier life for all: The case for cross-government action. APPHG and the Health Foundation; 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/AHealthierLifeForAll.pdf

- Schwartz CE, Keyl PM, Marcum JP, Bode R. Helping Others Shows Differential Benefits on Health and Well-being for Male and Female Teens. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009; 10(4): 431–48. Available from doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9098-1

- Yach D, speaking in: The Health Foundation. Healthier lives: a listening exercise. [Video] 2016. Available from: www.health.org.uk/healthier-lives-listening-exercise