Introduction

The purpose of this Practical guide is to support NHS organisations to apply a framework for measuring and monitoring safety (see Figure 1 on page 5). This framework was developed on behalf of the Health Foundation by Professor Charles Vincent, Ms Susan Burnett and Dr Jane Carthey. The research team drew on learning from the literature as well as a survey of current practice as they developed the framework.

This guide introduces the framework and explains how it can help those working in the NHS answer the question ‘How safe is our care?’ and bring about constructive change. The guide describes some broad principles to bear in mind when using the framework and provides some prompts for each of the framework’s dimensions to help people focus on some of the main challenges to understanding safety.

The guide also provides a brief summary of the research underpinning the framework and details of further resources available to find out more.

* For full details, see the 2013 Health Foundation spotlight report, The measurement and monitoring of safety: www.health.org.uk/measuresafety

The framework for measuring and monitoring safety

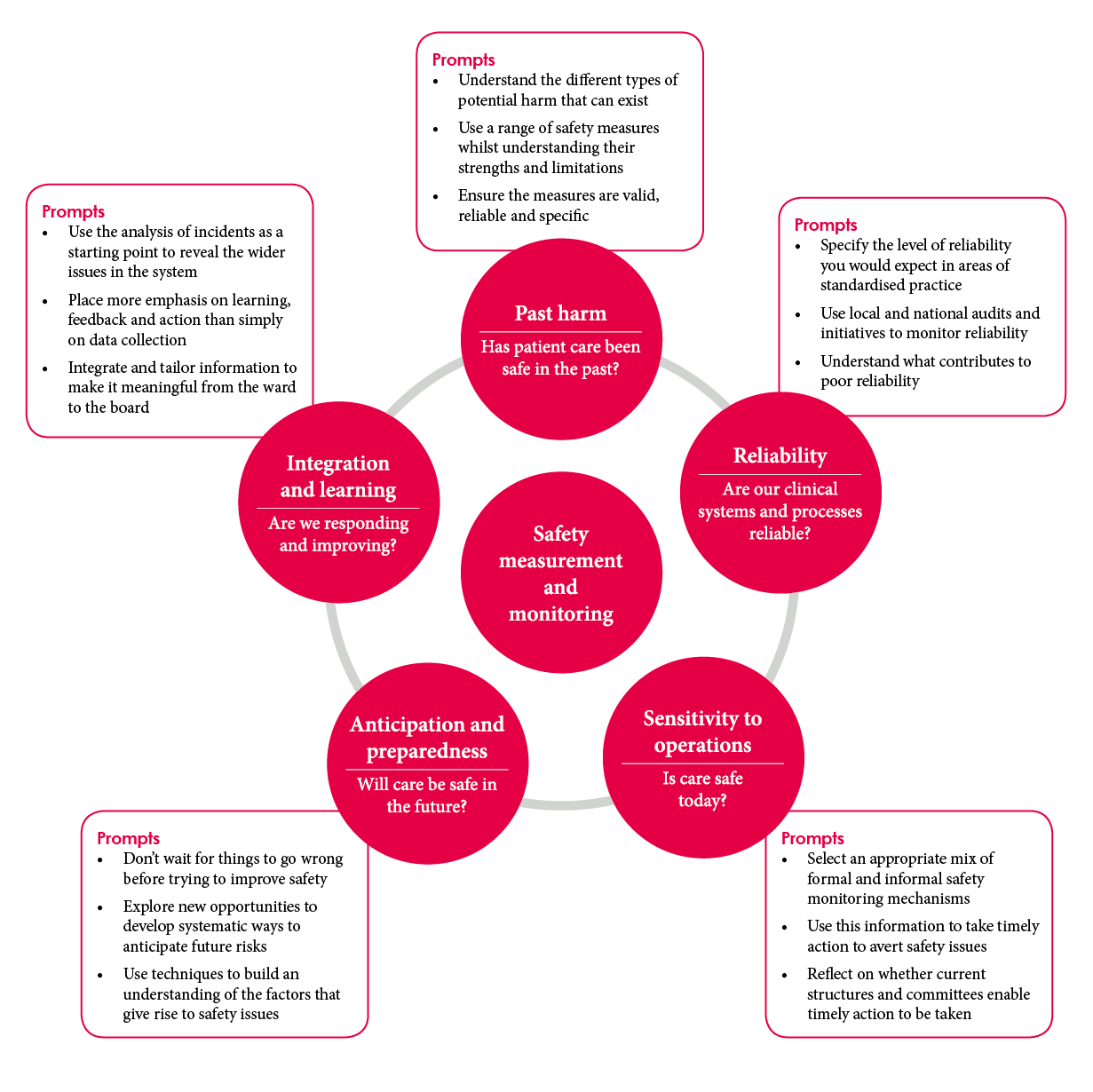

The framework consists of five ‘dimensions’ and associated questions that organisations, units or individuals can use to help understand the safety of their services. Used over time, this will help to give a rounded, accurate and ‘real time’ view of safety and will support efforts to identify those areas which present the greatest opportunity for safety improvement.

Figure 1: A framework for measuring and monitoring safety

Why does the NHS need a new approach?

A huge volume of data is currently collected on medical error and harm to patients. There have also been many tragic cases of health care failure, as well as a growing number of major reports on the need to make health care safer. However, despite this focus, the answer to the question ‘How safe is our care?’ remains elusive. This is illustrated in a number of ways:

- Progress has been made to reduce the incidence of specific health care associated harms, such as MRSA and Clostridium difficile, but this does not tell us how safe people are today, just the degree to which they were affected by specific causes of harm in the past.

- Increasingly sophisticated measures of mortality have been developed, but differences in methodology make comparisons over time very difficult.

- There have been a number of successful, high profile national programmes to improve safety, such as Matching Michigan which aimed to reduce central line infections, but the different ways in which people collect data can make comparisons across units ‘almost meaningless’.

These issues demonstrate that individual organisations need to think carefully about how they can better understand the safety of their services, while balancing the requirements of regulators and external bodies.

One of the recommendations made by Don Berwick in his 2013 review into patient safety was that all NHS organisations should:

‘…routinely collect, analyse and respond to local measures that serve as early warning signals of quality and safety problems such as the voice of the patients and the staff, staffing levels, the reliability of critical processes and other quality metrics. These can be ‘smoke detectors’ as much as mortality rates are, and they can signal problems earlier than mortality rates do.’

The framework asks a series of open questions that can help to drive responsibility for measuring and monitoring safety to the front line, ensuring that measures are relevant to the local context, as well as the requirements of external bodies. The costs for NHS organisations to respond to nationally mandated data collection is high – around £300-£500 million a year – so it is vital that resources are used as effectively as possible.

How can the framework help?

As shown in Figure 1, the framework suggests five questions that can be asked by individuals, units, teams, departments and organisations across all health care settings – including primary, community, mental health and acute care. The questions are:

- Past harm – Has patient care been safe in the past?

- Reliability – Are our clinical systems and processes reliable?

- Sensitivity to operations – Is care safe today?

- Anticipation and preparedness – Will care be safe in the future?

- Integration and learning – Are we responding and improving?

By using the framework and considering these questions, organisations and individuals will be able to understand and discuss more clearly what it means to be safe. The framework shifts the emphasis away from focusing solely on past cases of harm, and more on real-time performance and measures that relate to future risks and the resilience of organisations.

† www.nhs.uk/news/2012/05may/Pages/mrsa-hospital-acquired-infection-rates.aspx

‡ www.health.org.uk/blog/hospital-wide-mortality-rates-and-measuring-quality-smoke-alarm-not-smoke-screen

§ www.health.org.uk/publications/lining-up-how-is-harm-measured

¶ A promise to learn – a commitment to act. www.gov.uk/government/publications/berwick-review-into-patient-safety

** Challenging Bureaucracy. NHS Confederation, 2013. www.nhsconfed.org/Publications/reports/Pages/challenging-bureaucracy.aspx

From theory to practice

The Health Foundation road-tested the framework with three NHS organisations, and sought feedback through a public consultation and a patient safety summit. The feedback we received was very positive, but stressed the importance of helping people understand how the framework can best be applied in practice – something that this guide aims to contribute to. We are funding an improvement programme to explore more fully how the framework can be applied in various practice settings. We are also working closely with organisations such as the Care Quality Commission to inform how they inspect the safety of organisations.

What might the framework mean for different levels of the health system and for the public?

- Front line health and care professionals should reflect on the value of data currently collected, and identify opportunities to collect more meaningful data about the safety of their services. When we tested the framework, front line professionals told us that it widened their thinking about patient safety, and helped to clarify the value of collecting different data and measures.

- Managers and support staff should work with clinical staff to ensure that learning, feedback and action are prioritised following the review of safety information. When we tested the framework, managers told us that the framework helped them to reflect on ‘where they are’. They said that it enabled them to see the flaws within their current systems and challenged how they view their own roles.

- Board members should ensure that staff have the time and resources to explore new measures so that the safety information they ask for, and receive, is meaningful. When we tested the framework, boards told us the framework provided them with a structure to analyse what they were doing, that it widened their thinking about safety and helped them to ‘make the connections’ between different safety measures and activities.

- Government, regulators and national agencies should design their systems for oversight and regulation in a way that allows organisations to demonstrate their safety, rather than their compliance with prescriptive, centrally-mandated measures. When we tested the framework, board members and managers spoke of their frustration about the current focus on externally imposed measures above those that are important to front line staff for improving safety.

- As a result, Patients and the public should increasingly expect to see information that is important to them, which reflects the safety of the service they are using today, not just how harmful it has been in the past. When we spoke to patients and the public, they told us that their relationships with staff, and how staff communicate with them, are the most important factors to feeling safe.

Useful prompts for using the framework

Figure 2 overleaf suggests some prompts for using the framework. These aren’t a substitute for the findings of the research, but are intended as a helpful reminder of its key points if you are applying the framework to your own context.

Figure 2: The framework for measuring and monitoring safety – and useful prompts for using it in practice

Key principles for using the framework

You should bear in mind the following key principles when applying the framework to your own practice.

To get the most out of the framework, you should be:

- open

- thoughtful

- reflective

- inquisitive.

Be open

When seeking measures to answer the five questions in the framework, you would not expect to have comprehensive measures for each. For example, there are fewer measures to understand how risks are anticipated and prepared for than there are for measuring past harm. The framework works most effectively if it is used as part of an honest assessment about where your strengths and weaknesses are in terms of understanding safety, and to then target your efforts on those weaknesses.

Be thoughtful

We received feedback that the framework is ‘deceptively simple’. Accessibility is one of its strengths, however this should not hide the depth of thought and consideration that effectively using the framework requires. The questions in the framework may be simple, but the underlying issues are complex and will undoubtedly be challenging to solve. They will require the input of patients and carers and staff from across the full range of clinical, managerial and support functions, with sufficient time made available for in-depth discussion.

Be reflective

When considering the types of measures to help answer the five questions in the framework, discussion is likely to lead to a reflection of current practice and to highlight some difficult decisions which may need to be made. Reflective questions might include:

- What information do you currently collect?

- Does it add value and contribute to your understanding of how safe the care you provide is?

- Is your organisation’s data accurate, comparable and meaningful?

- Should your organisation stop collecting some types of information and start collecting others?

- Does your organisation have enough of the right kind of support and expertise to develop, collect, analyse and use meaningful information?

Be inquisitive

The actual process of asking questions, rather than stipulating answers and ‘ticking them off’, will increase the sense of ownership of safety in an organisation. An approach which focuses on measures that are helpful in the day-to-day management of care, and that also provide evidence to meet the requirements of external bodies, will offer benefits to staff, patients and the public like.

Summary of the research

Past harm – Has patient care been safe in the past?

There are relatively few ways in which care can go right and many more in which it can go wrong. Therefore, organisations need to understand the different types and causes of patient harm, which can be caused by:

- delayed or inadequate diagnosis (eg misdiagnosis of cancer or a patient not seeking an appointment after noticing rectal bleeding)

- failure to provide appropriate treatment (eg rapid thrombolytic treatment for stroke or prophylactic antibiotics before surgery)

- treatment (eg surgical complications or the adverse effects of chemotherapy)

- over-treatment (eg drug overdose or painful treatments of no benefit to the dying)

- general harm (eg delirium or dehydration)

- psychological harm (eg depression following mastectomy).

The multiple types of harm require more than just a single measure. A range of measures might include: mortality statistics, systematic record review, selective case note review, reporting systems and existing data sources – taken together, they give units and organisations the best chance of understanding harm, but the strengths and limitations of each must be understood.

The measurement of past harm will always be a cornerstone to understanding safety. Measures need to be specific and tracked over time to help to assess whether care in a particular area, and overall, is becoming safer. Measures also need to be valid and reliable, selected from a broad range of approaches according to their suitability to the care setting.

Reliability – Are our clinical systems and processes reliable?

Reliability in other industries can be thought of as the probability of a system functioning correctly over time. But in health care it can be difficult to define exactly what ‘functioning correctly’ means. It is possible to do this in those areas where protocols have been developed to standardise treatments – for instance, in the management of acute asthma in emergency departments or the management of diabetes in primary care. However, there will always be occasions where guidance either cannot or should not be followed.

The measurement of reliability in health care should focus on areas where there is a higher degree of agreement and standardisation. This is typically achieved through clinical audit measures, set either locally (eg percentage of patients with two complete sets of vital signs in a 24-hour period) or nationally (eg percentage of all inpatient admissions screened for MRSA).

Although clinical audits have value, they tend to focus on specific points of care processes. Many national initiatives have introduced ‘care bundles’, where previously separate care processes are brought together to reduce the chance of aspects of care being missed. A more holistic, though more challenging, approach requires understanding reliability across an entire clinical system and exploring the factors that contribute to poor reliability. This could include staff accepting poor reliability as normal or a lack of feedback mechanisms.

Sensitivity to operations – Is care safe today?

Safety needs to be managed on a day-to-day or even minute-by-minute basis, whether it be the clinician monitoring a patient, or the manager monitoring the impact of staffing and resource levels. It involves a state of heightened awareness that enables information to be triangulated in real time, and action to be taken to tackle identified problems before they threaten patient safety.

Formal and informal mechanisms that organisations can use to support this ‘sensitivity to operations’ in health care might include:

- safety walk-rounds, which enable operational staff to discuss safety issues with senior managers directly

- forums, such as operational meetings, handovers and patient/carer meetings, to act as sources of intelligence on the safety of services

- day-to-day conversations between teams and managers

- patient safety officers actively seeking out, identifying and resolving patient safety issues in their clinical units

- briefings and debriefings, such as at the end of a theatre list, to reflect on learning

- patient interviews, letting patients tell their story to identify any threats to safety.

Some measures have been externally mandated, such as the staff and patient surveys, as well as the regional development of Quality Surveillance Groups.

Anticipation and preparedness – Will care be safe in the future?

The ability to identify future hazards and potential problems in clinical services is an essential part of delivering safe care. This is best achieved by encouraging questioning, and creating opportunities for individuals and teams to discuss scenarios, so that teams become resilient in the face of unexpected events. The research tells us that this is an area where other safety-critical industries are more developed than the NHS.

Documents such as risk registers are commonplace in the NHS, where local risks are identified and graded. However, their ability to help to anticipate whether care will be safe in the future is open to question. This may be more effectively achieved in other ways, such as the following:

- Toolkits for identifying and monitoring risks, for example those developed in the Health Foundation’s Safer Clinical Systems programme.

- Safety cases, which offer a means by which organisations can use a range of evidence to demonstrate that a system is acceptably safe.

- Studies of safety culture and climate have shown that the culture and climate have a correlation with patient outcomes and staff injuries.

- Staff indicators of safety, such as sickness absence rates and staffing levels, can help to forecast an organisation’s ability to safely provide care in the future.

Integration and learning – Are we responding and improving?

There are many different sources of safety information available to organisations, but these must be integrated and weighted if risks and hazards are to be effectively understood and prioritised so that effective action can be taken. This must also be done in different ways at different levels. For example, the level of detail and specificity required by a unit would be different to the summarised, high level information that a board would need for an overview of the safety across all of an organisation’s services.

A disproportionate amount of effort tends to be spent on data collection, whereas an effective system for incident reporting would be made up of information, analysis, learning, feedback and action. Incident analysis should go further than explaining the nature of the event, to help to identify wider problems in the system.

Feedback, action and improvement are vital to making systems safer in the future. There are many different types of local feedback mechanisms in use, ranging from individual discussions to safety newsletters and web-based feedback. The challenge at the higher levels of organisations is to integrate the information available to draw wider lessons and to spread learning right across the organisation where appropriate, without losing the granularity that makes information real for individuals.

Examples of how to do this include producing organisation-wide regular learning reports, hosting learning seminars or tracking performance across a number of safety themes on a regular (eg quarterly) basis. Developments in the visual representation of data and technological solutions can help to do this in the future.

Where can I find out more?

Further resources

Full details of the research and the development of the framework are available in:

- Vincent C, Burnett S, Carthey J. The measurement and monitoring of safety. The Health Foundation, 2013. Available at: www.health.org.uk/measuresafety

- You can also download The measurement and monitoring of safety as a free ebook from the Apple iTunes store for iPad and iPhone or from Google Play for Android devices.

There are also a number of videos and webinars about the framework and managing safety proactively:

- Professor Katherine Fenton talks about managing safety proactively and how the framework can be used to achieve this: www.health.org.uk/multimedia/video/katherine-fenton-on-managing-safety

- Six leading patient safety experts discuss managing safety proactively and how the framework could help to improve patient safety: www.health.org.uk/multimedia/video/managing-safety-proactively

- In a December 2013 webinar, Charles Vincent talks to Bill Lucas about the framework and answers questions from webinar participants: www.health.org.uk/multimedia/video/measuring-monitoring-safety

You might also be interested in:

The Health Foundation’s patient safety resource centre pulls together evidence and resources to help people deliver safe care:

http://patientsafety.health.org.uk

Every month the Health Foundation’s Research Scan looks at thousands of journals, then selects and summarises around 60 of the most interesting studies about healthcare improvement. Sign up for the scan at:

www.health.org.uk/learning/research-scan