Key points

- A great deal of effort is being put into reducing emergency admissions in England. While some efforts may have been successful, the number of emergency admissions has nonetheless grown by 42% over the last twelve years.

- The impact on acute hospitals is being compounded by the increasingly complex needs of patients requiring an admission. In 2015/16, one in three emergency patients admitted for an overnight stay had five or more health conditions, up from one in ten in 2006/07. Emergency admissions have grown particularly rapidly for older patients, increasing by 58.9% since 2006/07 for people aged 85 years or older. These trends are challenging for hospitals to manage, since patients with more conditions spend longer in hospital once admitted.

- Hospitals have attempted to manage these pressures by shortening length of stay. While the number of emergency admissions has grown by 3.2% each year on average, the total number of bed days for patients admitted as an emergency has grown only by 0.3% per year. Around a third of all emergency admissions are now zero-day stays, meaning that the patient does not need to stay overnight.

- Reductions in length of stay have been particularly dramatic for patients with multiple health conditions. Patients with five or more conditions who were admitted overnight spent an average of 10.8 nights in hospital in 2015/16, compared with 15.8 nights in 2006/07. The number of zero-day stays for these patients has increased by 373% over the same period.

- While these reductions in length of stay suggest there have may been improvements in productivity, these trends have not fully offset the impact of overall growth in emergency admissions: the total number of bed days devoted to patients admitted as an emergency has increased from 27.1 million days in 2006/07 to 28 million days in 2015/16.

- These trends are making it increasingly difficult for hospitals to reliably deliver elective care. Although the overall balance between emergency and elective bed days has not changed markedly over the last decade, bed occupancy rates have increased and are now routinely above 90% in England. With such little spare capacity, hospitals are struggling to accommodate sudden and unpredictable increases in emergency admissions, meaning that elective care is cancelled or postponed.

- For more than a decade, health policy in England has sought to reduce demand for emergency care by making improvements to other parts of the health care system. The rationale is that around 14% of all emergency admissions are for conditions that might be manageable in primary care, and good quality primary care has been linked to fewer admissions. However, it may not be possible to reduce demand for a large number of admissions even with effective out-of-hospital care. Contractions in funding for social care funding also be affecting admissions.

- It is more important than ever to understand which approaches are effective at reducing emergency admissions and why. Unfortunately, there are comparatively few well-evidenced examples of specific interventions achieving sustained reductions in emergency admissions, in part because the NHS does not always have access to evaluations of the type needed. As a result, it is often not clear what impact changes are having, and what are the elements that could be spread.

- Interventions must be well designed, based on a deep understanding of the underlying problems with care delivery, and evolve over time in response to learning. This will only be possible if clinicians and managers have the time, resources and skills to lead improvement work. Health and social care data sets will also need to be brought together, to help analysts understand the issues with care delivery and assess the impact of changes.

Introduction

This winter has been a story of profound mismatch between illness and NHS resources. More seriously unwell people needing admission have arrived at the front doors of A&E departments in England than NHS hospitals have had the staff or beds to cope with.

The results are now familiar: long, undignified and sometimes potentially unsafe waits for patients in corridors and in the back of ambulances, while other patients are having to cope with last-minute cancellations of their planned treatments to make room for the influx of emergencies. A large number of patients have not been discharged from hospitals even though they are deemed medically fit to leave, meaning they continue to occupy beds.

A great deal of effort is being put into reducing emergency admissions in England. The motivation for this is three-fold. Firstly, hospital care is the most expensive element of the health service and, in a cost-constrained system, resources must be carefully managed. Secondly, hospital admissions can expose certain patients (particularly older patients) to risk of infections. These patients can also rapidly lose the strength needed to maintain an independent life after leaving hospital. Thirdly, many patients admitted to hospital would prefer to be treated at home or in a medical facility close to home – or to avoid needing to seek urgent treatment in the first place.

Efforts to reduce emergency admissions are seen among the 44 Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships and the 50 new care models vanguards, which are being assessed on (among other things) reducing emergency bed days per 1,000 population. Releasing money from the Better Care Fund involves agreeing local plans to reduce emergency admissions. More generally, assumptions about the future growth of emergency admissions are seen throughout the central management of the health care system, including the locally agreed contracts between providers and commissioners (which specify no more than a 2.3% growth planned for 2018/19).

The efforts to reduce emergency admissions are part of a longer-term ambition to move away from health care being delivered in acute hospitals to finding alternative ways to manage patients at home or in the community. Many health systems have this ambition, with almost all of the 35 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations seeing reductions in acute hospital beds, enabled by advances in medical technology and shortening the lengths of hospital stays. However, there are concerns over the capacity of the NHS to respond to high levels of demand, with bed occupancy rates now routinely above 90%. Meanwhile, the UK already has the third lowest bed numbers in the European Union, the second highest rate of bed occupancy and shorter than average lengths of stays.

A clear understanding of the nature and drivers of demand for emergency admissions is needed now more than ever. This briefing aims to provide an overview of trends in emergency admissions over the past decade, and a summary of the best evidence behind some of the interventions being deployed to stem what might look like to many, an inexorably rising trend.

Part one: what are the pressures?

What has been happening to emergency admissions over the 12 years from 2006?

An emergency admission is one where a patient is admitted to hospital urgently and unexpectedly (ie the admission is unplanned). Emergency admissions often occur via A&E, but can also occur directly via GPs or consultants in ambulatory clinics.

Over the last 12 years, the number of emergency admissions in England has increased by 42%, from 4.25 million in 2006/07 to 6.02 million in 2017/18. This is equivalent to a growth rate of 3.2% each year on average. The financial implications for the NHS are considerable. Data on the total costs of emergency admissions are not yet available for 2017/18, but we know they cost the NHS in England £17.0 billion in 2016/17 – a growth of £5.5 billion compared with their cost in 2006/07. , These are likely to be underestimates, as they do not include all costs, such as those accrued following hospital discharge.

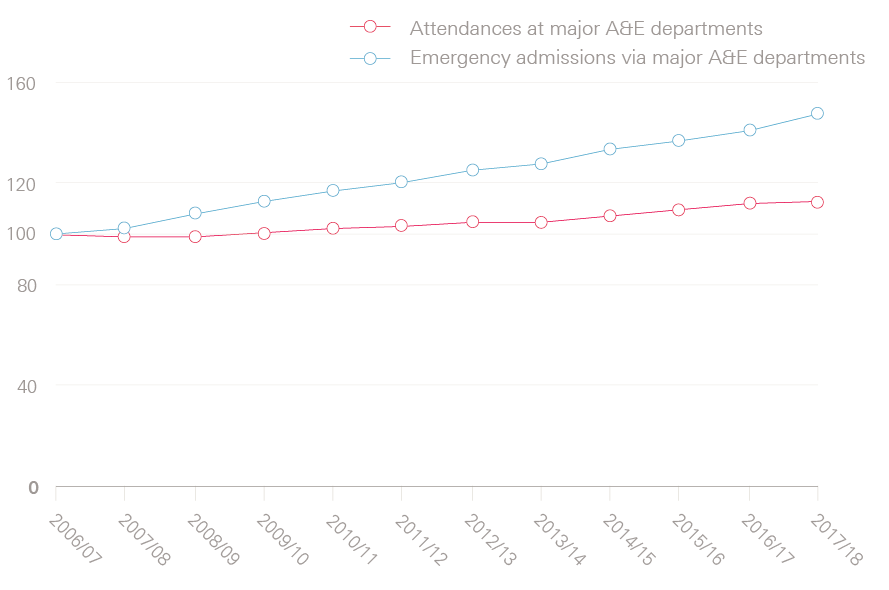

The growth in emergency admissions (at 42%) was substantially higher than UK population growth at 9% over the same period. It has also far outstripped increases in the number of patients arriving at major A&E departments, which has grown by only 13%. In fact, the divergence between emergency admissions and A&E attendances is much greater than these numbers show, since not all emergency admissions occur through A&E. Once we remove ‘direct’ admissions (where patients are admitted directly by GPs or consultants in ambulatory clinics, bypassing A&E), we find that emergency admissions have grown by 48% – almost four times more than the growth in A&E attendances, as shown by Figure 1.

Figure 1: Relative change in the number of attendances at and emergency admissions from major A&E departments from 2006/07 to 2017/18 (index 2006/07=100)

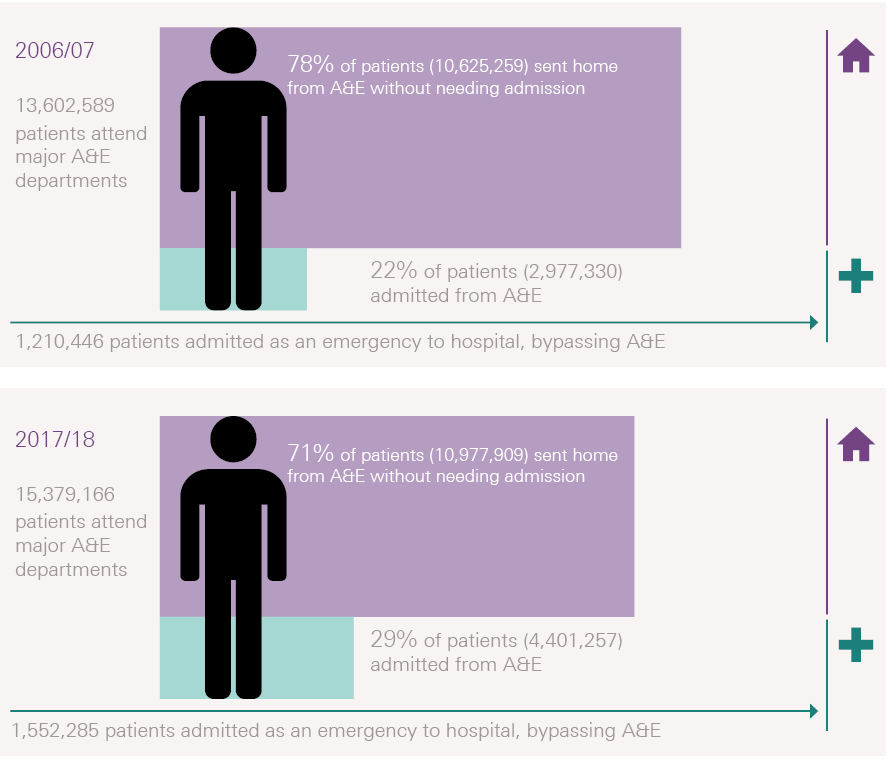

A much greater proportion of people attending major A&E departments are being admitted to hospital than before: 29% in 2017/18, which has steadily risen from 22% in 2006/07 (Figure 2). This has occurred despite efforts to divert patients with more minor problems who arrive at major A&E departments to lower intensity forms of care, for example by placing GPs within A&E departments.

Figure 2: A smaller percentage of A&E patients were sent home without admission in 2017/18 than 2006/07

Why are more patients being admitted to hospital as an emergency?

One possible explanation for these trends is that more patients arriving at A&E now have more severe or complex needs, and are therefore more likely to require inpatient admission. Testing this hypothesis is challenging, since NHS data contain comparatively little information on patients who attend A&E but are not admitted. What we can do, however, is examine the characteristics of patients who are being admitted as an emergency, which are available for inpatients from the Hospital Episodes Statistics for the period 2006/07 to 2015/16.

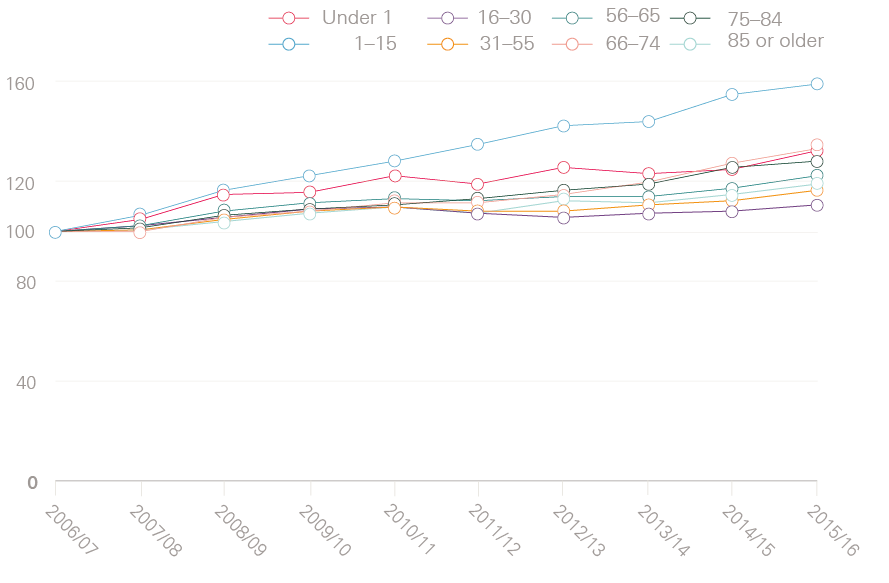

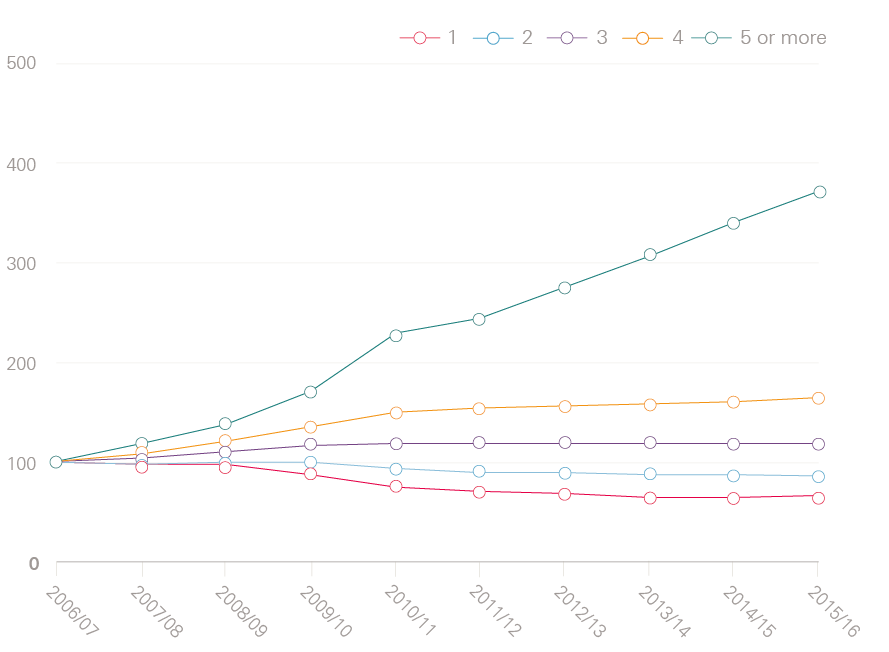

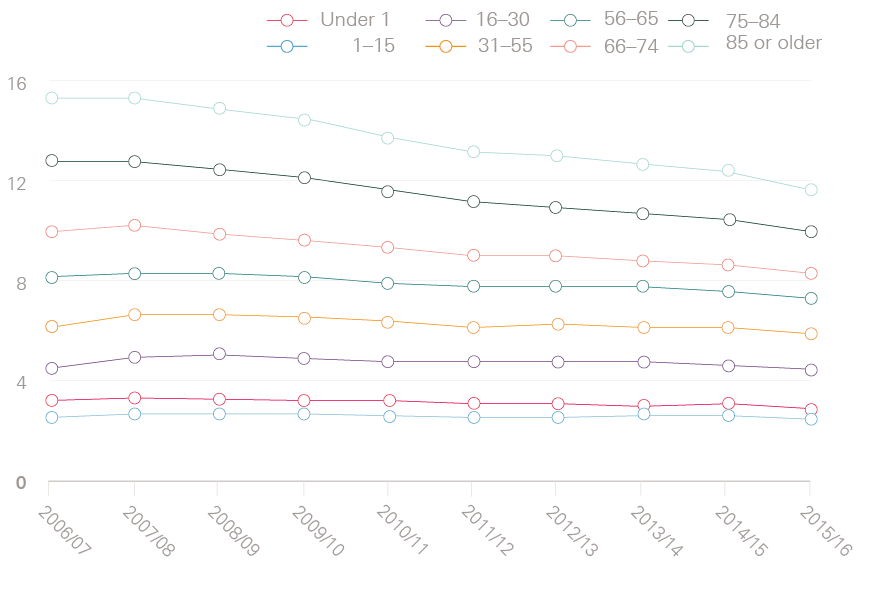

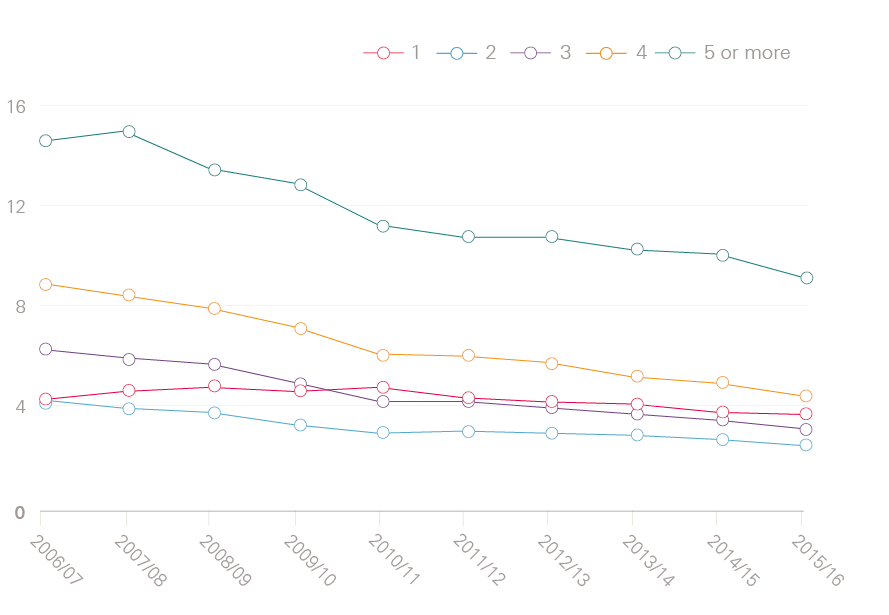

As Figure 3 (on page 8) shows, there has been a particularly sharp rise in the number of emergency admissions for patients aged 85 years or older (up 58.9%) and in admissions for patients with multiple health conditions. One in three patients admitted to hospital as an emergency in 2015/16 had five or more health conditions, compared with just one in ten in 2006/07 (a percentage increase of 271%). In fact, the number of emergency admissions for patients with just one condition fell over the same period (by 34%).

This analysis of health conditions includes long-term conditions (such as heart failure), acute conditions (such as acute myocardial infarction), maternity events, and trauma (such as transport accidents). We have adopted a simple approach to classifying these conditions, based on applying very broad categories of diseases and symptoms that correspond to chapters in the International Classification of Diseases (10th revision) to Hospital Episode Statistics data. This means that, for example, we have grouped all diseases of the circulatory system together, so that if a patient has acute myocardial infarction with a history of hypertension, this counts only once in Figure 3. The approach has the advantage of being fairly robust to changes in how hospitals record health conditions (for example, if hospitals are becoming increasingly vigilant in recording hypertension amongst patients with other heart problems, then this would not affect our results). However, if a patient had a trauma (such as a road traffic accident) and has broken a limb, this would be recorded as two separate conditions. While estimates vary depending on which types of conditions and events are included, the broad trend in Figure 1 is supported by national surveys of older patients and primary care data.,

These statistics suggest that the impact of emergency admissions is greater than shown by the headline figures for the number of admissions – not only are hospital teams dealing with more emergency admissions than ever before, but they are also caring for patients with more complex needs. The changes in the characteristics of admitted patients may reflect broader changes in the population (as there has been a growth in the number of people living with long-term conditions) and improvements in the quality of hospital care (since more patients are surviving a hospital stay, but may then be admitted again at a later date).The pattern does not seem to support another possible explanation for rises in emergency admissions that is sometimes mooted, which is that hospitals are admitting more patients to improve their performance against the four-hour A&E waiting time target. If this was the case, we would expect to see that patients are more likely to be admitted today than patients with comparable needs several years ago, but recent research has found the opposite.

Figure 3: Relative change in the number of emergency admissions per year (index 2006/07=100)

Figure 3a: Emergency admissions by age group

Figure 3b: Emergency admissions by number of health conditions

How long do patients admitted as an emergency stay in hospital?

Despite the increasing complexity of conditions affecting patients admitted to hospital as an emergency, they are spending less time in hospital once admitted. There has been a particularly marked change in zero-day stays – ie where patients are admitted, treated and discharged on the same day. These made up 32% of emergency admissions in 2016/17, compared with 26.5% in 2006/07. There has been a reduction in longer stays too. Figure 4 shows the trends for patients who stay overnight, and measures length of stay based on the number of nights these patients spend in hospital. The average number of nights spent in hospital fell from 8.5 nights in 2006/07 to 7.5 nights in 2015/16 among this group of patients.

Figure 4 shows that reductions in length of stay have been particularly noticeable for older patients and those with multiple conditions. Focusing on patients aged 85 or older who are admitted as an emergency and stay overnight, the average number of nights in hospital fell from 15.3 nights in 2006/07 to 11.6 nights in 2015/16. Over the same time period, the average number of nights in hospital for patients with five or more conditions fell from 15.8 nights to 10.8 nights. Both of these groups have also seen substantial increases in the zero-day stays, with growth rates standing at 178% for those aged 85 or older, and 373% for patients with five or more conditions.

These reduced lengths of stay are potentially good for patients, since they mean less time exposed to the stresses and risks associated with being in hospital. These changes have also helped hospitals manage the increasing number of patients admitted. However, they have not fully offset the growth in emergency admissions, and overall there has been an increase in the total number of bed days devoted to patients admitted as an emergency. Calculating this increase requires some assumptions, since the Hospital Episode Statistics do not contain the time of admission and discharge, meaning that it is not possible to calculate the length of stay for patients being admitted and discharged on the same day. However, if we assume that those patients spend half a day in hospital on average, and add this to the total number of overnight stays, then we find that the total number of bed days devoted to patients admitted as an emergency has increased from 27.1 million days in 2006/07 to 28 million days in 2015/06 – an increase of 3.3%. This is equivalent to a growth rate of 0.3% per year on average.

Figure 4: Average length of stay for patients who are admitted to hospital as an emergency and stay overnight

Figure 4a: Average length of stay (in days) by age group

Figure 4b: Average length of stay (in days) by number of health conditions

What are the implications for elective care?

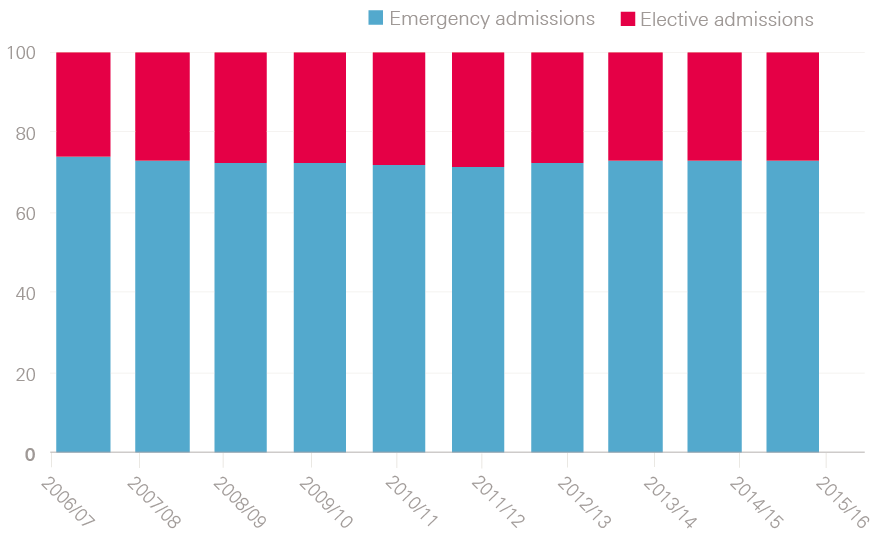

Given the changes in emergency admissions, it’s surprising that the balance between emergency and elective care has in some ways remained so stable. Figure 5 shows the proportion of bed days devoted to emergency versus elective admissions for NHS trusts, with zero-day stays included as 0.5 days in each case. While the number of bed days devoted to patients admitted as an emergency increased by 3.3% between 2006/07 and 2015/16, the growth in bed days for elective admissions was more than double this, at 7.4%. There has therefore been a slight increase in the proportion of NHS hospital beds that are taken up by elective care. Not included in the figure is the growth in NHS-funded elective care provided by private hospitals and treatment centres, which now accounts for around 6% of all elective admissions for NHS patients.

It is possible that the balance between elective and emergency care has changed since 2015/16, as pressures on hospitals have become more severe. Still, it seems likely that the effect of emergency admissions on elective care is not so much about the increased number of patients, but rather more about the unpredictability of how, when and why they are admitted to hospital, combined with a reduction in spare capacity to absorb sudden increases in emergency admissions. As previously noted, the total number of beds in hospitals in England has been reducing. The precise number is hard to estimate, in part due to fluctuations in the number of temporary beds, but NHS England puts the number of general and acute beds at around 102,690 in 2016/17, compared with 126,976 in 2006/07. This means that bed occupancy rates have increased significantly, and are now routinely over 90%, well over the 85% benchmark recommended by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine. These trends mean that at times of pressure, hospitals increasingly have to cancel or delay elective procedures, since otherwise beds are not available for emergency patients.

Figure 5: Proportion of total bed days for emergency admissions and elective admissions

* Unless indicated otherwise, all data presented in this chapter were obtained from NHS England (www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2017-18/). In some instances, it was necessary to supplement this with analysis of more detailed Hospital Episode Statistics data.

† The statistic for 2006/07 had to be obtained from the Hospital Episode Statistics, since NHS England’s data for 2006/07 do not include the number of direct admissions (ie those not coming through an A&E department). There are some differences between the Hospital Episode Statistics and the data source used by NHS England, but these have negligible impact here.

‡ Costs of emergency inpatient care in 2006/07 were adjusted for market prices in 2016/17 using the GDP deflator. The GDP deflator measures price inflation and is the quotient of nominal GDP and real GDP times 100 (www.gov.uk/government/collections/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp).

§ Major A&E departments are those that operate a 24-hour, consultant-led service with full resuscitation facilities and designated accommodation for A&E patients. All analysis excludes single specialty departments, minor injury units and others. If these were included, the number of patients attending A&E departments would have increased by 26% between 2006/07 and 2017/18.

¶ Growth rates are expressed as cumulative percentage changes, with 2006/07 baselined at 100.

** We estimated the number of direct admissions in 2006/07 from the Hospital Episode Statistics. All other statistics are from NHS England.

†† Recorded conditions or events from ICD10 Chapters 1–22.

‡‡ We performed sensitivity analysis where we excluded ICD10 codes recording health events such as trauma (Chapters 19-22). With this restriction we found that one in four patients admitted to hospital as an emergency in 2015/16 had five or more health conditions, compared with just one in twenty in 2006/07 (a percentage increase of 362%).

§§ Analysis of Hospital Episodes Statistics data. Where patients were transferred from one hospital to another, we counted only the first admission. Growth rates are expressed as cumulative percentage changes, with 2006/07 baselined at 100.

¶¶ Health Foundation analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics data.

*** Health Foundation analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics data. Where patients were transferred from one hospital to another, we included the subsequent hospital stay when calculating the number of nights spent in hospital.

††† CQC figures for 2016/17 (http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/state-care-independent-acute-hospitals.pdf).

‡‡‡ Health Foundation analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics data. Where patients were transferred from one hospital to another, we included the length of the subsequent hospital stay.

Part two: what can be done to address emergency admissions?

There are, broadly, three options to meeting this additional demand: reducing the number of emergency admissions, shortening length of stay, or increasing the amount of resources dedicated to acute care. This chapter summarises the evidence for the first option, since it has been a central aim of health policy in England for more than a decade to reduce demand for admitted emergency care by making improvements to other parts of the health care system. The theory is that some emergency admissions are preventable through earlier intervention and treatment elsewhere. Though of course, from the perspective of the patient being admitted to hospital as an emergency, the event does not often seem ‘avoidable’.

Below, we present our summary of what the published research tells us about the potential of hospital admission avoidance programmes. It draws on the research that the Health Foundation has funded and conducted in this area, as well as our knowledge of the wider literature. Although it is not a systematic review, we have identified the main issues. We look at several types of intervention in turn, including those related to general practice, social care and technology, and examine the rationale for each as a means to reduce emergency admissions, the scope for improvements, specific areas of focus and the evidence of impact so far.

Does better general practice care help prevent emergency admissions?

General practices offer an alternative place of treatment for minor conditions, and good quality care in general practice can also prevent the development of more severe health problems that require hospital admission.

It is notoriously difficult to estimate the number of admissions that could be avoided through better primary care. One approach that is often used is to measure the number of emergency admissions that are for ‘ambulatory care sensitive conditions’. These include long-term conditions such as asthma, where good quality care should prevent flare-ups; acute conditions such as infections, where timely and effective care stops the condition deteriorating; and conditions that are preventable by vaccination, such as influenza and pneumonia.

Our analysis of the Hospital Episode Statistics shows that these instances accounted for 14% of emergency admissions in 2015/16. This suggests there is some scope to reduce admissions by improving the quality of primary care, though it is probably an overestimate since some admissions are not preventable even if they are for ambulatory care sensitive conditions.

Insights are available from research studies that measure specific aspects of the quality of general practice care and examine whether there is a correlation with emergency admissions. These insights can help determine where efforts would be best focused. Many studies have examined the accessibility of general practice, with one finding that where practices are more likely to offer an appointment to patients in advance, their patients experience fewer emergency admissions. Another study estimated that 26.5% of all unplanned A&E attendances in England (5.77 million per year) were preceded by the attending patient being unable to obtain a general practice appointment that was convenient to them, though comparatively few of these A&E attendances will have resulted in an admission.

Another strand of the literature has examined the continuity of care that patients receive. The Health Foundation examined data for people aged between 65 and 85 and found that patients who saw the same GP over time were admitted to hospital less often than similar individuals who saw the same GP less often. Our findings have since been replicated using a slightly different method among patients aged 65 years and older. Fewer studies have examined other aspects of general practice care, such as appointment duration or the quality of the interpersonal relationships that patients report with their GPs.

While these studies have shown a link between the quality of general practice care and emergency admissions, there are few well-evidenced examples of specific interventions having an impact in this regard. For example, a study examining the impact of extending opening hours in general practices in Greater Manchester found that patients registered to general practices with extended access were 26.4% less likely to initiate A&E visits for minor complaints than patients at other practices, though this equated to only a 3.1% reduction in A&E visits overall, and information was not available on admission rates. There were also questions around the sustainability of the extended opening hours within workforce constraints. One of the main initiatives to improve continuity of care was a national requirement to introduce named accountable GPs. This intervention did not seem to meet its objective to improve how often patients saw their usual GP, at least in the first nine months. A longer-term evaluation is needed to assess whether the intervention became more effective with time, and examine if there were impacts on admission rates.

There has been more research into the use of technology to support changes to the delivery of primary care. One example is telemonitoring, where patients are asked to monitor their health on a regular basis (for example, weight or blood pressure) and the data are transmitted to health care practitioners working remotely to assist with the diagnosis or ongoing management of health conditions. Findings have been mixed, with one of the largest trials in the area (the Whole System Demonstrator) initially finding reduced emergency admission rates, but later concluding that these were likely the result of a methodological artefact associated with how the trial was conducted. Another large study found that telehealth increased the number of emergency admissions, possibly because patients became more concerned about what the data were saying about their health, and in some cases the situation required admission.

Technology is increasingly being used to increase the availability of services. One study examined the impact of an approach whereby all patients wanting to see a general practitioner were asked to speak to a GP on the phone before being given an appointment for a face-to-face consultation; this found a considerable reduction (38%) in face-to-face appointments, but no indications of a reduced use of secondary care. An evaluation of GP at Hand (which allows registered patients to speak to a GP by video via an app) is being commissioned by NHS Hammersmith & Fulham Clinical Commissioning Group.

Further research studies are needed to test the impact of changes to general practice care that aim to improve accessibility or continuity, since there are already indications that improvements in these areas might lead to reductions in secondary care activity as well as being good for patients. There is also a need for studies examining other aspects of the quality of general practice care, including the clinical quality and effectiveness of the care provided, and their implications for patients and the NHS. There is a need for linked primary and secondary care data that can follow a patient through the local health system, since this will help with the design, implementation and evaluation of interventions.

Does improving the availability and quality of social care reduce emergency admissions?

It is worth considering the connection between social care and emergency admissions. Once admitted, people with a need for social care often experience long stays in hospital, which may increase their risk of experiencing an event with an adverse health impact, such as an infection. The benefit of avoiding emergency admissions may therefore be particularly high among people with a need for social care, from the perspective of both the patient and the NHS. There has been a severe contraction in publicly funded social care since 2010, and this might well have had consequential impacts on the NHS as well as for the individuals concerned.

A recent study examining data from six areas of England uncovered high rates of emergency admission among people newly admitted to care homes, with care home residents in these areas who were aged 65 or over experiencing 0.78 emergency admissions each per year on average, compared with around 0.11 for England as a whole. Although we would expect admission rates to be higher for the care home population (since these individuals often have high levels of need), there may still be opportunities to make improvements to care to reduce admission rates for this section of the population. One estimate is that 40% of admissions from care homes were for conditions that could potentially be managed outside of the hospital setting or avoided altogether (such as pneumonia or urinary tract infections). People receiving high-intensity social care in the community may have an even higher likelihood of emergency admission than care home residents. There may also be a high rate of admissions among people who have not been able to access social care despite a need for it, though data are not available to quantify this.

While these studies suggest that people with social care needs experience relatively high rates of emergency admissions, it has not been clear where activities should be focused for the best impact. Most studies have examined ways to support more timely and effective discharge from hospital, rather than ways to prevent hospital stays. Studies have also struggled to unpick issues relating to the availability of social care from those related to the quality of the social care provided. Further research is needed to measure different aspects of the quality of social care and to connect these to emergency hospital admissions. It would help if health and social care data were linked together routinely and made available for research and analysis.

There are some examples of effective interventions, including two recent studies of the enhanced support offered to residents living in care homes. One study, conducted by the Improvement Analytics Unit,26 looked at linking general practices to care homes in Rushcliffe, Nottinghamshire, and supporting newly-arrived care home residents to change to the nominated practice. This meant the residents could be reviewed frequently by GPs and practice nurses, and also fostered closer working relationships between care home staff and the NHS. The evaluation found that residents receiving enhanced support were admitted to hospital as an emergency 23% less often than similar residents in similar care homes in comparable parts of England. A similar picture has emerged from an evaluation by the Nuffield Trust, which examined a different intervention in care homes and concluded there had been a 35% reduction in emergency admissions. The Improvement Analytics Unit is conducting further work on admissions from care homes.

In relation to people receiving social care in the community, a major research study was the Partnerships for Older People Projects, which tested 146 interventions across 29 sites between 2006 and 2009. The national evaluation of the whole programme concluded that each £1 invested in the programme reduced expenditure on emergency admissions by £1.20, though it was unclear which of the 146 interventions were most effective. Eight of the particularly promising interventions were then examined in more detail, yet were not found to be associated with reduced admissions.,

Does integrated care reduce emergency admissions?

More integrated care has been a priority for the NHS for some time, the rationale being that patients with complex health care needs often experience fragmentation in care, their treatment being divided up between many different professionals and organisations. In turn, this means there are risks to quality and safety from duplication or omissions of care, as well as poor patient experience. While much of the value of integrated care is related to the possibility of improving patient experience and other aspects of care quality, the major initiatives have nearly always had an aim to reduce emergency admissions.

There is a clear rationale for integrated care as a way to improve experience of care, but what is the scope to reduce hospital admissions? We saw in the previous section of this briefing that there has been particularly rapid growth in emergency admissions for patients with complex needs. Yet it is unclear how many of these admissions arose from the specific care delivery problems that are being targeted by integrated care initiatives, compared to other problems with care delivery (such as the poor availability of social care, or difficulties accessing general practices). As a result, the scope of integrated care to reduce emergency admissions is far from clear. To address this issue, it would help to establish a way to measure care fragmentation, since it would then be possible to examine more systematically how emergency admission rates vary according to the extent of the fragmentation experienced.

Many attempts have been made to make care more integrated, including creating multidisciplinary teams to provide more holistic care for patients and efforts to replicate the practices of ward rounds within community settings (‘virtual wards’). Few evaluations have pointed convincingly to reductions in admissions, and indeed evaluations of multidisciplinary teams have often found increases. Various explanations have been put forward, including the possibility that some interventions have been poorly implemented or evaluated too early.

More research is needed. Care fragmentation should ideally be measured routinely in the NHS. Evaluations of integrated care initiatives should also routinely examine a greater range of outcomes than emergency admissions, including health, wellbeing and patient reported outcomes.

Can changing the urgent and emergency care pathway reduce emergency admissions?

Emergency hospital admissions are only one aspect of a much broader urgent and emergency care system, which includes services such as urgent care centres, walk-in centres and NHS 111. In some instances, these may be able to provide treatment more effectively than major A&E departments and at lower cost, particularly where patients have relatively minor complaints. As such, there may be justification for changing the broader urgent and emergency care pathway. Initiatives that encourage or direct patients to seek treatment for minor complaints from these other services might reduce pressures on major A&E departments, though potentially without a direct impact on emergency admissions.

It is challenging to estimate what proportion of patients attending A&E could have received treatment elsewhere. The previous section showed that the majority (71%) of A&E attendances do not result in emergency admission, but many of these patients may still have required treatment from an A&E team. A better approach is to look at how many A&E attendances were for patients self-referring for minor conditions: one study using data from Greater Manchester found these comprised a third of all A&E department visits.

There are several possible areas of focus. Comparatively few studies have examined how A&E visits and emergency admissions vary according to the availability and quality of urgent care, but some insights are available in relation to NHS 111. There were concerns that the introduction of NHS 111 might have increased pressures on A&Es, in part because the service had been relying on non-clinically trained staff, who might have adopted an overly cautious approach to managing risk by directing patients to A&E who did not need to attend. Studies have therefore examined whether increasing clinical input into NHS 111 calls – which is now the current policy – might reduce pressures on emergency care.

One of these studies addressed 1,474 patients in Cambridgeshire who had called NHS 111 and been advised to attend A&E. When GPs subsequently reviewed these patients, they recommended emergency department attendance for only 27% of cases. A more recent research project by the Health Foundation examined out-of-hours NHS 111 calls for children and young people in Hammersmith and Fulham, Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster. By linking NHS data sets together, we were able to examine how often patients visited A&E in the ten hours following the call to NHS 111, rather than just the advice given. We compared patients who were advised to manage their health needs at home with patients who were referred by the NHS 111 service to an out-of-hours GP. After adjusting for differences in the characteristics of the two groups (including their age and symptoms), we found that GP review was associated with 14% fewer attendances at A&E departments. This reduction in A&E visits seemed to be concentrated in the minor injury units, as there was no discernible impact on visits to major A&Es, or emergency admissions. The findings suggest that clinical input during NHS 111 might provide valuable reassurance to callers, but not avert pressures on major A&E departments. Further studies are needed that examine data from other areas and also for adults.

Relatively few interventions have been evaluated, so it is hard to know which are effective. However, there are some indications that changes to the urgent and emergency care pathway are increasing the overall volume of activity in the urgent and emergency care system. For example, the initial introduction of NHS 111 increased overall activity by 4.7–12% across pilot sites, while an evaluation by the Improvement Analytics Unit found that the redesign of urgent and emergency care in Northumberland increased the total number of visits to minor and major A&Es by 13.6%. These findings may have arisen because patients perceived that urgent and emergency care had become a more attractive place to seek treatment, either because it was more accessible or because care was of a higher quality.

Studies are needed that link data together from multiple sources to examine the pathways that individuals take through the urgent and emergency care system. These might examine what proportion of A&E visits were preceded by an attempt to contact other urgent care services (including NHS 111 and primary care), and why these patients attended A&E despite alternatives.

What approaches can be applied to reduce readmissions?

Around 400,000 emergency admissions each year are readmissions, meaning that the patient had been discharged from hospital within the previous 30 days. Readmission rates have been increasing over time in the NHS, with 6.75% of discharges in 2015/16 being followed by an emergency admission in 30 days, compared with 6.5% in 2006/07. However, these increases in readmissions seem to be in line with what would be expected (given the increasing complexity of the patients who are originally admitted to hospital), and a patient being discharged from hospital today does not have a higher likelihood of being readmitted than a similar patient a decade ago.

Some readmissions are considered preventable, by making improvements to the quality and safety of the initial hospital stay, transitional care, or post-discharge support. Estimates vary for the scope to reduce readmissions, with studies concluding that anywhere between 5% and 79% of readmissions are potentially preventable, depending on the method used and the care setting. The most effective interventions seem to be multimodal, involving several components and multiple health care practitioners, and often include an element to support individuals to manage their own health and care. Because of the cost of these interventions, it may be necessary to target them closely on the individuals most likely to benefit, for example through the use of predictive risk models.

Can emergency admissions be reduced by making improvements outside of the health and social care system?

Approaches to reducing emergency admissions need not be restricted to the health and social care system. Increases in demand may be linked to the informal social support available to individuals, their socio-economic resources (including employment) and their general ability to manage their own health and health care. Efforts that strengthen these other areas might have consequential benefits to the NHS, including reduced demand for emergency care.

Relatively little is known about this area, but the Health Foundation has started a programme of analytics that uses person-level data to measure the social and economic situation of individuals, and the potential consequences for demand for health care as well as outcomes and the quality of care provided. These projects require linkages to be made between NHS data sets and with the wider public data. Our first pieces of published research in this area (expected later in 2018) will examine self-management capability, and informal social support, with more to follow.

Conclusion

It has been a central aim of health policy in England for more than a decade to reduce demand for emergency care by making improvements to other parts of the health care system. There is scope for doing so. For example, research has shown that patients who are registered at general practices that offer more accessible care experience fewer emergency admissions, as do patients who tend to see the same GP over time. There is significant potential for impact in this area, as around 14% of all emergency admissions are for conditions that are (at least in theory) manageable in primary care. Policies are now in place to improve access to general practice and reverse the trend of underfunding and understaffing, but they will take time to bear fruit.

Improving care within social care settings might also have an impact, with care home residents experiencing high rates of admission. The picture is unknown for patients who have a need for social care but that is unmet by the current system: the contraction of publicly funded social care since 2010 has been severe. There are signs too that emergency admissions are influenced by factors outside of the health and social care system, including the degree of informal social support available to individuals and their general ability to manage their own health and health care.

The National Audit Office found that a minority of CCGs have reduced their emergency admissions over the past three years, but noted that it was not clear why. In terms of specific interventions that have aimed at reducing admissions, despite more than a decade of trying, there are comparatively few well-evidenced examples that have worked. There are some examples of success, so hope is not lost, but examples are few and far between.

The question now is why so few interventions have been able to demonstrate avoided or reduced admissions. Part of the problem is that the NHS does not always have access to evaluations of the type needed, although initiatives such as the Improvement Analytics Unit are helping. As a result, it is often not clear what impact changes are having, and what elements could be spread. Some interventions may also need to be better designed, and this is dependent on health care practitioners having the time, skills, knowledge and resources to shape, test and evaluate the impact of interventions. One priority is to link health and social care data sets together routinely and make these available to analytical teams, so that they can work with practitioners to understand the issues with care delivery and conduct the evaluations.

But what our analysis has shown is that a growing proportion of people who are being admitted to hospital are older and have many conditions, and it is also likely that caring for these patients is also increasingly challenging outside hospital. The possibility remains that even the most responsive and well-coordinated services in primary and community care will struggle to prevent sudden deterioration that requires a hospital bed. The implications of this are uncomfortable for a system that has, in many areas, planned for an overall reduction in acute hospital beds.

This briefing has focused on the emergency admission of patients: there are also efforts underway to reduce lengths of stay, and offer more support after discharge, which is in line with what many patients and families want. It is important for policymakers to recognise that additional resources may have to be channelled to the hospital sector, at the same time as supporting new interventions outside hospital. The reality of an ageing population is that both are equally vital.

References

- National Audit Office. Reducing Emergency Admissions. National Audit Office, 2018.

- OECD. OECD Health Statistics 2017. OECD; 2017. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm

- Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2006/07. Department of Health, 2008. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130104223439/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_082571

- NHS Improvement. NHS Reference Costs 2016/17 [Internet]. NHS Improvement, 2017. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/reference-costs/

- Office for National Statistics. Overview of the UK population: March 2017. Office for National Statistics, 2017. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/releases/overviewoftheukpopulationmarch2017

- Melzer D, Tavakoly B, Winder RE, Masoli JAH, Henley WE, Ble A, Richards SH. Much more medicine for the oldest old: trends in UK electronic clinical records. Age and Ageing. 2015; 44(1):46-53. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/44/1/46/2812316

- Dhalwani NN, O'Donovan G, Zaccardi F, Hamer M, Yates T, Davies M, Khunti K. Long terms trends of multimorbidity and association with physical activity in older English population. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016; 13:8. Available from: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-016-0330-9

- Laudicella M, Martin S, Li Donni P, Smith PC. Do Reduced Hospital Mortality Rates Lead to Increased Utilization of Inpatient Emergency Care? A Population-Based Cohort Study. Health Serv Res. 2017;1–22. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/1475-6773.12755

- Wyatt S, Child K, Hood A, Cooke M, Mohammed MA. Changes in admission thresholds in English emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2017;34(12):773–9. Available from: http://emj.bmj.com/content/emermed/34/12/773.full.pdf

- NHS England. Bed Availability and Occupancy Data – Overnight. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/bed-availability-and-occupancy/bed-data-overnight/

- NHS England. Operational update from the NHS National Emergency Pressures Panel. Available from: www.england.nhs.uk/2018/01/operational-update-from-the-nhs-national-emergency-pressures-panel/

- Glasby J, Littlechild R, Le Mesurier N, Thwaites R, Oliver D, Jones S, Wilkinson I. Who knows best? Older people’s contribution to understanding and preventing avoidable hospital admissions. University of Birmingham, School of Social Policy. 2016. Available from: www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/2016/who-knows-best.pdf

- Bankart MJ, Baker R, Rashid A, Habiba M, Banerjee J, Hsu R, Conroy S, Agarwal S, Wilson A. Characteristics of general practices associated with emergency admission rates to hospital: a cross-sectional study. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(7):558–563. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21515879

- Cowling TE, Harris MJ, Watt HC, Gibbons DC, Majeed A. Access to general practice and visits to accident and emergency departments in England: cross-sectional analysis of a national patient survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(624):434–439. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24982496

- Barker I, Steventon A, Deeny SR. Association between continuity of care in general practice and hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: cross sectional study of routinely collected, person level data. BMJ. 2017; 1;356:j84. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28148478

- Tammes P, Purdy S, Salisbury C, MacKichan F, Lasserson D, Morris RW. Continuity of Primary Care and Emergency Hospital Admissions Among Older Patients in England. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):515–522. Available from: www.annfammed.org/content/15/6/515.abstract

- Whittaker W, Anselmi L, Kristensen SR, Lau Y-S, Bailey S, Bower P, Checkland K, et al. Associations between Extending Access to Primary Care and Emergency Department Visits: A Difference-In-Differences Analysis. PLOS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002113. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002113

- Barker I, Lloyd T, Steventon A. Effect of a national requirement to introduce named accountable general practitioners for patients aged 75 or older in England: regression discontinuity analysis of general practice utilisation and continuity of care. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011422. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27638492

- McLean S, Sheikh A, Cresswell K, Nurmatov U, Mukherjee M, Hemmi A, Pagliari C. The impact of telehealthcare on the Quality and Safety of Care: A Systematic Overview. PLoS One. Public Library of Science; 2013;8(8):e71238. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071238

- Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, Dixon J, Doll H, Hirani S, Cartwright M, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3874. Available from: www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e3874

- Steventon A, Grieve R, Bardsley M. An Approach to Assess Generalizability in Comparative Effectiveness Research: A Case Study of the Whole Systems Demonstrator Cluster Randomized Trial Comparing Telehealth with Usual Care for Patients with Chronic Health Conditions. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(8):1023-36. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25986472

- Steventon A, Ariti C, Fisher E, Bardsley M. Effect of telehealth on hospital utilisation and mortality in routine clinical practice: a matched control cohort study in an early adopter site. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009221. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009221

- Newbould J, Abel G, Ball S, Corbett J, Elliott M, Exley J, Martin A, et al. Evaluation of telephone first approach to demand management in English general practice: observational study. BMJ. 2017;358:j4197. Available from: www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j4197

- Hauck K, Zhao X. How Dangerous is a Day in Hospital?: A Model of Adverse Events and Length of Stay for Medical Inpatients. Medical Care. 2011;49(12):1068-1075. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/Abstract/2011/12000/How_Dangerous_is_a_Day_in_Hospital___A_Model_of.5.aspx

- Wenzel L, Bennett L, Bottery S, Murray R, Sahib B. Approaches to social care funding: Social care funding options. The Health Foundation, 2018. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/approaches-social-care-funding

- Lloyd T, Wolters A, Steventon A. The impact of providing enhanced support for care home residents in Rushcliffe: Health Foundation consideration of findings from the Improvement Analytics Unit. London: The Health Foundation, 2017. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/IAURushcliffe.pdf

- Bardsley M, Georghiou T, Chassin L, Lewis G, Steventon A, Dixon J. Overlap of hospital use and social care in older people in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(3):133–139. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22362725

- Forder J. Long-term care and hospital utilisation by older people: an analysis of substitution rates. Health Econ. 2009;18(11):1322–1338. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19206085

- Sherlaw-Johnson C, Crump H, Curry N, Paddison C, Meaker R. Transforming health care in nursing homes: An evaluation of a dedicated primary care service in outer east London. Nuffield Trust; 2018. Available from: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/transforming-health-care-in-nursing-homes-an-evaluation-of-a-dedicated-primary-care-service-in-outer-east-london

- Windle K, Wagland R, Forder J, D’Amico F, Janssen D, Wistow G. The National Evaluation of Partnerships for Older People Projects: Executive Summary. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, 2009. Available from: www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/rs053.pdf

- Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, Georghiou T, Lewis G. An evaluation of the impact of community-based interventions on hospital use: A case study of eight Partnership for Older People Projects. Nuffield Trust, 2011. Available from: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/an-evaluation-of-the-impact-of-community-based-interventions-on-hospital-use

- Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, Georghiou T, Lewis GH. The Role of Matched Controls in Building an Evidence Base for Hospital-Avoidance Schemes: A Retrospective Evaluation. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(4):1679–98. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3401405/

- Roland M, Lewis R, Steventon A, Abel G, Adams J, Bardsley M, Brereton L, et al. Case management for at-risk elderly patients in the English integrated care pilots: observational study of staff and patient experience and secondary care utilisation. Int J Integr Care. 2012;12:e130. Available from: www.ijic.org/articles/abstract/10.5334/ijic.850/

- Anderson A, Roland M. Potential for advice from doctors to reduce the number of patients referred to emergency departments by NHS 111 call handlers: observational study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009444. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/11/e009444

- Wolters A, Robinson C, Hargreaves D, Pope R, Maconochie I, Deeny SR, Steventon A, et al. Predictors of emergency department attendance following NHS 111 calls for children and young people: analysis of linked data. bioRxiv. 2018;237750. Available from: www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/02/06/237750.

- Turner J, O’Cathain A, Knowles E, Nicholl J. Impact of the urgent care telephone service NHS 111 pilot sites: a controlled before and after study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003451. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/11/e003451

- O’Neill S, Wolters A, Steventon A. The impact of redesigning urgent and emergency care in Northumberland: Health Foundation consideration of findings from the Improvement Analytics Unit. The Health Foundation, 2017. Available from: www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/IAUNorthumberland.pdf

- Friebel R, Hauck K, Aylin P, Steventon A. National trends in emergency readmission rates: A longitudinal analysis of administrative data for England between 2006 and 2016. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020325. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/3/e020325

- Friebel R, Steventon A. The multiple aims of pay-for-performance and the risk of unintended consequences. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:827-831. Available from: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/25/11/827.info

- van Walraven C, Jennings A, Taljaard M, Dhalla I, English S, Mulpuru S, Blecker S, et al. Incidence of potentially avoidable urgent readmissions and their relation to all-cause urgent readmissions. CMAJ. 2011;183(14):1067–1072. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21859870

- Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, Wang Z, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1095–1107. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24820131

- Steventon A, Billings J. Preventing hospital readmissions: the importance of considering ‘impactibility,’ not just predicted risk. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(10):782-785. Available from: http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/qhc/early/2017/06/14/bmjqs-2017-006629.full.pdf

- OECD and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. United Kingdom: Country Health Profile 2017. State of Health in the EU country profiles, 2017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264283589-en