Key points

- In January 2019, the NHS published its 10-year Long Term Plan, including a commitment to improve NHS support in care homes, rolling out the Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) framework across England. One of the aims of the framework is to reduce emergency admissions from care homes which, although essential for delivering medical care, can expose residents to stress, loss of independence and risk of infection. Care home residents often prefer to be treated in the care home or avoid the need to seek urgent treatment in the first place. Therefore reducing emergency admissions could be good for residents, as well as help reduce pressure on the NHS.

- In this briefing, we firstly present our analysis of a national linked dataset identifying permanent care home residents aged 65 and older and their hospital use in the year 2016/17. In the second part of the briefing we synthesise learning from four evaluations of the impact of initiatives to improve health and care in care homes carried out by the Improvement Analytics Unit (IAU).

- Our analysis, using a new data linkage method that allows us to identify permanent care home residents aged 65 and older in NHS datasets, found that during 2016/17 care home residents went to A&E on average 0.98 times and were on average admitted as an emergency 0.70 times. The overall number of emergency admissions from care homes in 2016/17 was an estimated 192,000, comprising 7.9% of the total number of emergency admission for England for people aged 65 years or older. The overall number of A&E attendances from care homes was 269,000, comprising 6.5% of the total number of attendances for people aged 65 years and older. Reducing emergency hospital use from care homes therefore has the potential to reduce pressure on hospitals.

- A large number of these emergency admissions may be avoidable, with 41% of emergency admissions from care homes being for conditions that are potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside of a hospital setting, or that could have been caused by poor care or neglect.

- Surprisingly, emergency admissions are particularly high in residential care homes (0.77 admissions per resident per year) compared with nursing care homes (0.63 admissions per resident per year). This is the case even though residential care homes provide 24-hour personal care, while nursing homes also provide nursing care and therefore one would expect residential care home residents to be less seriously ill than nursing home residents. People in residential care homes attended A&E on average 1.12 times in the year 2016/7, compared with 0.85 times in nursing care homes. One possible explanation is that staff in residential care homes may have less support in managing health needs within the home, and therefore rely more on emergency services. Also, health needs may not be detected as early in residential homes as in nursing homes.

- The IAU has evaluated four initiatives to improve health and care in care homes that were associated with the NHS’s New Care Models programme. For several of these we concluded there were reductions in at least some measures of emergency hospital use for residents who received enhanced support: in Rushcliffe we found care home residents were admitted to hospital as an emergency 23% less often than a comparison group, and had 29% fewer A&E attendances; Nottingham City care home residents had 18% fewer emergency admissions and 27% fewer potentially avoidable admissions than a comparison group; and Wakefield residents had 27% fewer potentially avoidable admissions. In Sutton, however, the results were inconclusive.

- These initiatives included elements of the EHCH framework, which will be rolled out as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. Therefore, the work of the IAU shows that there is potential for the EHCH framework to reduce demand for emergency care from care homes, but it also points to some implementation challenges that need to be taken into consideration when rolling out the framework.

- Given the policy focus on improving care in care homes, both over the past few years and moving forward with the NHS Long Term Plan, understanding and monitoring the quality of health care provided to care home residents will be important, both to gauge the impact of national programmes and to help pinpoint areas of improvement, identify ‘active ingredients’ for a successful intervention and spread good practice.

- In this briefing, we synthesise learnings from our evaluations of the initiatives in Rushcliffe, Sutton, Wakefield and Nottingham City to pull out what seem to be key lessons for implementing the framework in care homes. These key lessons are that (i) there is greater potential to reduce emergency admissions and A&E attendance in residential care homes compared with nursing homes, (ii) co-production between health care professionals and care homes is key to developing effective interventions, (iii) access to additional clinical input by named GPs and primary care services and/or multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) may be a key element in reducing emergency hospital use, and finally (iv) our studies show that it is likely to take more than a year for changes to take effect – meaning it is important not to judge success too quickly.

- Finally, this briefing shows the importance of having access to linked administrative datasets to provide evidence to support policy making. It is important that these sorts of data are routinely and consistently collected and are easily accessible to both care providers and research teams if we are to understand residents’ health care needs and produce robust evaluations – and ultimately improve care for this vulnerable group.

Background

Nearly 340,000 older people in England live in residential or nursing care homes; this includes long-term residents as well as people living in a care home temporarily for respite care, short breaks and recovery. Census data suggest that 274,000 residents have a residential or nursing home as their usual place of residence; we refer to these people as permanent care home residents. These people rely on the care home staff to provide care and support so that they can live their lives while having as much independence as possible. They also often have health care needs that require care from the NHS. Care homes either provide 24-hour nursing care (nursing homes) or personal care only (residential care homes). Although resident characteristics within the two care home types differ,,, with nursing home residents more often nearing end of life,,, both often have complex health care needs,, with residential care home residents often also having nursing needs. In such cases, nursing is provided in residential care homes by community nurses.

Providing health care to care home residents is complex and both health and care services are under pressure. The number of long-term conditions care home residents often have, including dementia, incontinence, poor mobility, circulatory problems and angina, present clinical challenges that are compounded by the need to ensure medications for multiple conditions work well in conjunction with one another.,, The differing support needs of individuals, as well as different treatment preferences and risk profiles present additional challenges when determining the best treatment for care home residents.

Admission rates are not the only metric of interest when assessing health care delivered for care home residents, but they are important for three reasons. Firstly, although emergency hospital admissions are often essential for delivering medical care, they can expose a patient to stress, loss of independence and risk of infection, reducing a patient’s health and wellbeing after leaving hospital., Care home residents may be particularly adversely affected by a hospital admission since many residents are frail and are susceptible to losing muscle strength when confined to a bed. About 70% of care home residents have dementia and can find the hospital environment stressful and disorienting., Secondly, many patients admitted to hospital would prefer to be treated at home or in a medical facility close to home – or to avoid the need to seek urgent treatment in the first place. Thirdly, emergency hospital care is also the most expensive element of the health service and in a cost-constrained system needs to be carefully managed. If some emergency admissions from care homes can be avoided this may be good for both the individuals concerned and the NHS.

Compared with other patient groups, there is less evidence on the quality of health care that is provided to residents in care homes, although this may be changing. One reason for the relative lack of rigorous quantitative evaluations of quality of care in care homes is that, while the NHS collects standardised data on patients, there is no readily available database of care home residents that can identify which of the patients in these hospital data are living in care homes. Local authorities collect some data on residents who are receiving public support, but these are not collated nationally at person level, and they lack information on residents who pay for their own care, who comprise 41% of the care home population. Records kept by care homes (sometimes on paper only) are not collated centrally.

The available literature shows that, although the quality of care in care homes is mostly good, it can be variable,,,,, and is often reactive. There is also variability between care homes in their use of emergency services.,

There is also some variability between residential and nursing homes. For example, medication administration errors may be less likely among nursing homes. There is evidence that residential care home residents have higher ambulance call rates and higher emergency admission rates than nursing home residents. Furthermore, there are indications that GPs visit nursing homes more regularly than residential care homes, and that nursing homes are more likely to have an aligned GP and to pay a GP to provide services than residential care homes. Yet these differences seem to have gone largely unnoticed.

There has long been a recognition of the need to support and improve the quality of care for care home residents. The Five year forward view (2014) for the NHS in England included a commitment to support and stimulate the development of a new care model for enhanced health in care homes to improve the health care provided to care home residents and reduce hospital use. Subsequently, the Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) framework (2016), developed in collaboration with six NHS vanguards implementing the EHCH framework, set out three aims for the care model together to be delivered through seven core elements (see Box 1). The three aims for the model were:

• to ensure the provision of high-quality care within care homes

• to ensure that, wherever possible, individuals who require support to live independently have access to the right care and the right health services in the place of their choosing

• to ensure the best use of resources by reducing unnecessary conveyances to hospital, hospital admissions and bed days while ensuring the best care for residents.

In January 2019, the NHS published its 10-year Long Term Plan, which included a commitment to roll out the EHCH framework across England within the next decade, including stronger links between care homes and primary care services and more support by a consistent team of health professionals.

The IAU has to date evaluated four initiatives to improve health and care in care homes that were either EHCH vanguards or similar initiatives associated with the NHS’s New Care Models programme (Box 2 on page 23), one of which was quoted in the NHS Long Term Plan as a successful example of the EHCH framework. These evaluations have shown varying results across different outcome measures. These studies complement local evaluations of each EHCH vanguard that were undertaken as part of the NHS’s New Care Models programme. Overall, aggregate figures of EHCH vanguards indicate that emergency admission rates from care homes in vanguard areas remained broadly stable between 2014/15 and 2017/18, compared with higher rising rates for non-vanguard care homes over the same period. However, as in the case of the care home evaluations done by the IAU, there is likely to be variation within this group.

There is little robust comparative evidence of interventions in care homes that reduce emergency admissions, with much of the literature being based on case studies or of poor quality., Looking more broadly at patient outcomes, although evidence of the effect of interventions is often of poor quality,,, taken together potentially promising evidence is emerging on what combination of factors may be important for service development.

A common theme is multidisciplinary, partnership working and good relationships between care home staff and other professional groups.,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, This includes acknowledging care home staff’s knowledge and skills and working together to co-design changes;, the work being seen as legitimate and supported by contractual agreements;, and having protected time for training.,

Other elements showing encouraging signs are: training for care home staff;,,,,,,,,,,,,,, better preventative assessment and care management;,,,,,,, advance care plans; ,,,, end-of-life care planning; ,,,,, medicines management;,,, and data and monitoring. ,,,

Often evaluations either do not distinguish between residential and nursing homes, or are of only one type of care home. A 2011 systematic review of integrated care working between care homes and health care services pointed out that the majority of research was carried out in nursing homes, even though this was not where most older people in long-term care live. To our knowledge, other than some of the IAU studies,,, no studies have to date compared the impact of care home initiatives between residential and nursing homes, even though these differ in both staffing and resident characteristics.

The lack of good quality evidence on improvement initiatives in residential and nursing homes highlights the need for more robust evaluations in this field. Given the policy focus on improving care in care homes, both over the past few years and moving forward with the NHS Long Term Plan, understanding and monitoring the quality of health care provided to care home residents will be important, both to gauge the impact of national programmes and to help identify areas of improvement, identify ‘active ingredients’ for a successful intervention and spread good practice.

The IAU has to date evaluated four care home interventions as part of or similar to the EHCH framework. There were some mixed results on emergency hospital use but collectively these studies provide evidence that it is possible to improve health care in care homes. Our aim in this report is to provide a national analysis of emergency hospital use by care homes and synthesise what this is showing in order to inform the implementation of the NHS Long Term Plan.

* These figures were obtained from LaingBuisson and relate to 31 March 2016.

† Some care homes are ‘dual registered’, that is provide care both with and without nursing; these are not distinguishable from ‘nursing homes’ on the Care Quality Commission database. Therefore, for the purpose of IAU analyses of care homes, dual registered homes will be included in the ‘nursing home’ group. It is estimated that about 22% of ‘nursing home’ residents only receive personal care (LaingBuisson).

About this briefing

This briefing consists of two parts. The first part presents the results of a national analysis of emergency hospital admissions from care homes across England, to provide insight into how often care home residents are being admitted to hospital and the types of conditions that are causing their admissions. We use a novel technique of identifying care home residents at national level developed by the IAU that is more robust than other methods such as postcode matching, or surveys. We present figures for care home residents across England broken down by residential and nursing homes. We focus on emergency admissions for people aged 65 or older who are living permanently in care homes in England (excluding younger people and those moving to care homes for short periods of time). We included residents regardless of whether their stay was funded by the local authority, privately, or through NHS continuing care, but could not identify residents who were in the care home temporarily for respite care, rehabilitation, short breaks or other purposes.

The second part of the briefing draws on evaluations conducted by the IAU of four enhanced care packages provided to care home residents in Rushcliffe, Sutton, Nottingham City and Wakefield. By comparing and contrasting the different elements and contexts of these sites and bringing in other local evaluations of these sites, we explore the factors that may be most influential in reducing hospital admissions.

Lastly, our analysis points to the next steps for local health and social care providers and commissioners looking to better understand the quality of care being provided in order that they may improve care further.

Box 1: Seven core elements of the Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) framework

|

Care element |

Sub-element |

|

Enhanced primary care support |

Access to consistent, named GP and wider primary care service |

|

Medicine reviews |

|

|

Hydration and nutrition support |

|

|

Access to out-of-hours/urgent care when needed |

|

|

Multi-disciplinary team (MDT) support including coordinated health and social care |

Expert advice and care for those with the most complex needs |

|

Helping professionals, carers and individuals with needs navigate the health and care system |

|

|

Care element |

Sub-element |

|

Reablement and rehabilitation |

Rehabilitation/reablement services |

|

Developing community assets to support resilience and independence |

|

|

High quality end-of-life care and dementia care |

End-of-life care |

|

Dementia care |

|

|

Joined-up commissioning and collaboration between health and social care |

Co-production with providers and networked care homes |

|

Shared contractual mechanisms to promote integration (including continuing health care) |

|

|

Access to appropriate housing options |

|

|

Workforce development |

Training and development for social care provider staff |

|

Joint workforce planning across all sectors |

|

|

Data, IT and technology |

Linked health and social care datasets |

|

Access to the care record and secure email |

|

|

Better use of technology in care homes |

Source: NHS England. Enhanced Health in Care Homes framework (2016).

Methods

Descriptive analysis of emergency admissions from care homes nationally

The IAU developed a linked dataset that allowed us to look at A&E attendances and hospital admissions for permanent residential and nursing home residents across England for the first time. This dataset is based on data from 17 April 2016 to 15 April 2017.

Our method relied on accessing data on addresses that were collected by general practices in England. These were cross-referenced with a list of the addresses of care homes from the Care Quality Commission (CQC). Once care home residents were identified in this way, we linked this information to data on hospital admissions obtained from the Secondary User Services which is a national, person-level database that is closely related to the widely used Hospital Episode Statistics.

All processing of address information, and subsequent linkage of patient information was carried out by Arden & Greater East Midlands Data Services for Commissioners Regional Office (Arden & GEM DSCRO). The IAU subsequently carried out the analysis of the linked dataset using ‘pseudonymised’ information in a secure environment hosted by the Health Foundation. All data accessed by the IAU are anonymised in line with the Information Commissioner’s Office’s code of practice on anonymisation. Arden & GEM DSCRO and the Health Foundation are Data Processors on behalf of NHS England.

One limitation of our method is that it relies on patients updating their address information with their general practice after they move to a care home. As a result, we are likely to have identified only people who move to a care home on a permanent basis, and assume that we have excluded people who move to a care home temporarily for respite care, rehabilitation, short stays or other purposes. We will also have missed the early parts of care home stays if individuals did not update their address with their general practice immediately after moving to the care home.

Correction

Our method identified 195,296 permanent care home residents aged 65 or older in England at any point in time in 2016/17, compared with 274,040 according to Census 2011. Validation work has shown this is underestimated due to the method used to automate the cleaning of address information, but we found no evidence this underestimate varies across different age bands or geographies. To correct for this difference, all estimates on the number of emergency admissions have been multiplied by a factor of 1.403. Note, this correction does not affect our estimates of admissions rates.

Although the number of permanent care home residents in England, according to the census, dates back to 2011, we think it is still appropriate. We compared the distribution of age and gender at national level as well as patients aged 65 or older at regional level and found no substantial differences in variation between our linked dataset and census data. Data on all care home residents (including people living in a care home temporarily for respite care, short breaks or other purposes) shows little increase in the total number of residents, going from 328,600 in 2011 to 337,500 residents in 2016 (a 2.7% increase in five years).

Measuring emergency hospital admissions for care home residents

An emergency admission is one where a patient is admitted to hospital urgently and unexpectedly (that is, the admission is unplanned). Emergency admissions often occur via A&E departments but can also occur directly via GPs or consultants in ambulatory clinics. We identified these admissions from the hospital data linked to information about care home residents.

We also examined a subset of emergency admissions for specific conditions that were potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside a hospital setting (so-called ‘potentially avoidable’), namely:

- acute lower respiratory tract infections, such as acute bronchitis

- chronic lower respiratory tract infections, such as emphysema

- diabetes

- food and drink issues, such as abnormal weight loss and poor intake of food and water, possibly due to neglect

- fractures and sprains

- intestinal infections

- pneumonia

- pneumonitis (inflammation of lung tissue) caused by inhaled food or liquid

- pressure sores

- urinary tract infections

The list of conditions was originally developed by the CQC, as part of its analysis of older people receiving health and social care. These were unplanned admissions for conditions that were potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside of a hospital setting, or for conditions that could be caused by poor care or neglect. For example, some fractures may be avoidable with appropriate risk assessment and falls prevention, and urinary tract infections may be treatable within the community or care home. However, the complexity of the patient group means that ‘potentially avoidable’ admissions are not, when they become acute, necessarily avoidable. Context is also a factor in determining whether a ‘potentially avoidable’ admission could in fact have been avoided. For example, if a residential care home resident had pneumonia, hospital admission may be the most effective way of eliminating the infection quickly, whereas the available nursing support in a nursing home may have been able to oversee treatment of the same condition within the nursing home. Admissions for these conditions cannot always be avoided, especially given the complex and interacting health needs of care home residents. However, the enhanced support available in care homes could be expected to have greater impact on admissions for these conditions than others.

Further research is needed to validate the appropriateness of these conditions as a marker of avoidable admissions for the care home population. In the meantime, the data presented can only be taken as an illustration of the range of health conditions for which care home residents are admitted to hospital, some of which are potentially avoidable.

We expressed the number of admissions as rates per person per year. The rates were calculated as the total number of hospital admissions for all care home residents during 2016/17 divided by the number of days spent in the care home across all residents. That was then multiplied by 365 to provide a rate per person per year. Thus, two care home residents who stay in the care home for six months each would have counted towards one year in the rate.

In addition to looking at how often care home residents are admitted to hospital, we also examined the average length of hospital stay. For patients who stayed in hospital overnight, we calculated the length of their hospital stay as the number of nights spent in hospital. Patients who were admitted and discharged from hospital on the same day were counted as having spent half a day in hospital.

Long-term conditions

To investigate the level of complexity of the health needs of the care home population, we calculated the prevalence of certain long-term conditions and markers of frailty. Using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis codes recorded in either primary or secondary diagnosis fields in inpatient hospital data, we calculated the Charlson Index,, as an aggregate measure of the burden of disease, and the long-term conditions listed by Elixhauser, , as well as conditions related to frailty. To calculate these, we used inpatient data from the three years prior to 2016/17 (or prior to the date a patient moved into a care home if in 2016/17). If a resident did not have an inpatient admission, it is not possible to determine if they had any of these conditions; therefore, these were only calculated for the subset of residents who had a prior hospital admission.

Review of four case studies

The IAU has to date evaluated four initiatives to improve health and care in care homes that were either EHCH vanguards or similar initiatives associated with the NHS’s New Care Models programme. A review was conducted to identify key themes and learnings from the evaluation reports related to these four initiatives. The aim of this analysis was to identify patterns in relation to the ‘inputs’ each site invested (that is, ‘what was done’ locally) with a view to identifying any common themes that may prove useful in understanding impact, as measured by the IAU in terms of secondary hospital use.

We examined the five IAU reports evaluating the impact of the four care home initiatives:

- Two reports on Principia enhanced support in Rushcliffe between August 2014 and August 2016,

- Sutton Homes of Care between January 2016 and April 2017

- Wakefield Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) between February 2016 and March 2017

- Nottingham City CCG between September 2014 and April 2017.

In addition to the five studies carried out by the IAU, this briefing, where applicable, also draws on local evaluation reports for each of the sites and the EHCH framework itself to assess to what extent the elements of the EHCH framework were implemented. These reports were:

- Cordis Bright (2018) NHS Nottingham City CCG. Enhanced Health in Care Homes vanguard evaluation: final report (available upon request from NHS Nottingham City CCG)

- SQW (2018) Evaluation of Sutton Homes of Care Vanguard report

- Wakefield Public Health Intelligence Team 2018 report on the evaluation of a holistic assessment approach to: supporting care home and independent living schemes

- The NHS’s New Care Models framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes.

All documents were examined using a thematic analysis approach with the pre-existing EHCH framework used to identify and code key themes. In addition to the pre-existing framework, the researchers familiarised themselves with the studies and local evaluation reports with a view to identifying additional factors and themes that could assist in understanding. The documents were coded into key themes to better enable the identification of patterns.

‡ Pseudonymised datasets have been stripped of identifiable fields, such as name, full date of birth and address. A unique person identifier (such as NHS number) has been replaced with a random identifier. This random identifier is used to identify hospital activity from the same patient over time, but cannot be used to identify an individual.

§ Our method was based on the primary diagnosis code associated with an admission.

Results

Descriptive analysis of care homes nationally

Care home resident population

We estimate that a total of 398,000 people aged 65 years or older lived in one of 15,800 care homes in England at some point during 2016/17, and were followed for an average of 227 days during that year. This equates to an average of 274,000 people aged 65 years or older living in a care home as their main place of residence at any point in time in 2016/17. It is estimated that about 80% of the total care home population for this age group reside permanently in the homes, with the remainder of residents living in the homes temporarily.,

An estimated 193,000 older people lived in residential care homes and 213,000 in nursing homes as their main place of residence at some point in 2016/17, equating to about 135,000 residents aged 65 years or older living in residential homes and 139,000 in nursing homes at any time. Table 1 presents characteristics of the residential and nursing home population. The average age in the care homes at any point in time was broadly similar between residential and nursing homes (86 vs 85 years) and both had more female residents (74% and 69%, respectively). The levels of socio-economic deprivation, as described by the Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles, of the areas that the residential and nursing homes were located in were more or less evenly split across the different quintiles in both care home types. Residential care homes tended to be smaller than nursing homes (38 vs 59 beds) (Table 1).

For those residents who had a hospital admission in the three years prior to either 17 April 2016 (if already resident) or to moving to a care home in 2016/17, we calculated that nursing homes had on average slightly higher levels of long-term conditions among their residents than residential care homes at any one time. Of the list of conditions included in the Elixhauser list, the majority were more prevalent in nursing homes, with the exception of hypothyroidism (13% vs 12%). Similarly, nursing homes had on average slightly higher levels of frailty among their residents, for example in levels of incontinence, mobility problems and pressure ulcers (Table 1).

Table 1: Estimated characteristics of the residential and nursing home population

|

Residential |

Nursing |

All residents |

|

|

Average number of residents aged 65 or older living in a care home in 2016/17 |

135,000 |

139,000 |

274,000 |

|

Age in years |

85.6 (8.0) |

84.7 (8.0) |

85.1 (8.0) |

|

Men (%) |

26.2 |

31.2 |

28.8 |

|

Days in 2016/17 in a care home |

235 (129) |

219 (132) |

227 (131) |

|

Residential |

Nursing |

All residents |

|

|

Socio-economic deprivation** |

|||

|

Most deprived fifth (%) |

16.9 |

17.1 |

17.0 |

|

Second most deprived fifth (%) |

20.8 |

18.9 |

19.9 |

|

Middle fifth (%) |

21.7 |

22.2 |

22.0 |

|

Second least deprived fifth (%) |

22.4 |

22.1 |

22.2 |

|

Least deprived fifth (%) |

18.2 |

19.7 |

19.0 |

|

Rural area (%) |

20.3 |

18.3 |

19.3 |

|

Number of beds in the care home |

38 (19) |

59 (26) |

48 (24) |

|

Health conditions recorded in the three years prior to joining a care home in 2016/17†† |

|||

|

Average Charlson Index |

2.00 (1.62) |

2.24 (1.72) |

2.12 (1.68) |

|

Average number of Elixhauser comorbidities |

2.79 (2.02) |

3.10 (2.15) |

2.95 (2.09) |

|

Cancer (%) |

6 |

7 |

6 |

|

Cardiac arrhythmias (%) |

31 |

33 |

32 |

|

Chronic pulmonary disease (%) |

17 |

18 |

18 |

|

Congestive heart failure (%) |

14 |

15 |

15 |

|

Deficiency anaemia (%) |

8 |

9 |

8 |

|

Dementia (%) |

53 |

54 |

53 |

|

Depression (%) |

15 |

16 |

15 |

|

Residential |

Nursing |

All residents |

|

|

Diabetes (%) |

18 |

21 |

19 |

|

Fluid/electrolyte disorders (%) |

23 |

28 |

26 |

|

Hemiplegia or paraplegia (%) |

3 |

7 |

5 |

|

Hypertension (%) |

58 |

58 |

58 |

|

Hypothyroidism (%) |

13 |

12 |

12 |

|

Liver disease (%) |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Peripheral vascular disease (%) |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

Renal disease (%) |

19 |

20 |

19 |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis (%) |

5 |

6 |

5 |

|

Rheumatic disease (%) |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Valvular disease (%) |

9 |

9 |

9 |

|

Average number of frailty related comorbidities |

1.72 (1.39) |

1.98 (1.52) |

1.85 (1.46) |

|

Cognitive impairment (delirium, dementia, senility) (%) |

48 |

52 |

50 |

|

Falls or fractures (%) |

48 |

47 |

47 |

|

Depression (%) |

19 |

19 |

19 |

|

Functional dependency (%) |

11 |

16 |

14 |

|

Incontinence (%) |

9 |

14 |

12 |

|

Mobility problems (%) |

18 |

24 |

21 |

|

Pressure ulcers (%) |

8 |

13 |

11 |

Note: Numbers are calculated to provide estimates of the care home population at any one time.Numbers presented are either mean (standard deviation) or percentage.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

How often do residential and nursing home residents attend A&E?

We estimate that there were in total 269,000 A&E attendances from care homes. As would be expected, care home residents attended A&E more frequently than the general population aged 65 or older (Table 2). Care home residents attended A&E on average 0.98 times per person per year, whereas overall, people aged 65 or older attended A&E 0.43 times. These figures mean that 6.5% of all A&E attendances for people aged 65 or older in England are for care home residents, even though care home residents account for just 2.8% of the older population.

There were about 151,000 A&E attendances from residential care homes and 117,000 from nursing homes. Residential care home residents had on average 1.12 A&E attendances per person per year, compared with 0.85 in nursing homes. This equates to about 32% more A&E attendances from residential than nursing homes. In residential homes, 40% of A&E attendances did not result in an admission; in nursing homes this was 35% (Table 2).

How often are residential and nursing home residents admitted to hospital as an emergency?

We estimate that care home residents aged 65 or older experienced an estimated 192,000 emergency admissions to hospital. As expected, care home residents were admitted to hospital as an emergency more frequently than the general population aged 65 or older (Table 2). Care home residents experience one of these admissions 0.70 times per year, whereas people aged 65 or older experience 0.25 of these admissions per year on average. These figures mean that 7.9% of all emergency admissions for people aged 65 or older in England are for care home residents, even though care home residents account for just 2.8% of the older population.

There were an estimated 104,000 emergency admissions for residents aged 65 or older from residential care homes and 88,000 from nursing homes. Rates of emergency admissions were higher in residential care homes than nursing homes, with residential care home residents experiencing 0.77 emergency admissions per person per year, compared with 0.63 in nursing homes.

What are residential and nursing home residents admitted to hospital for?

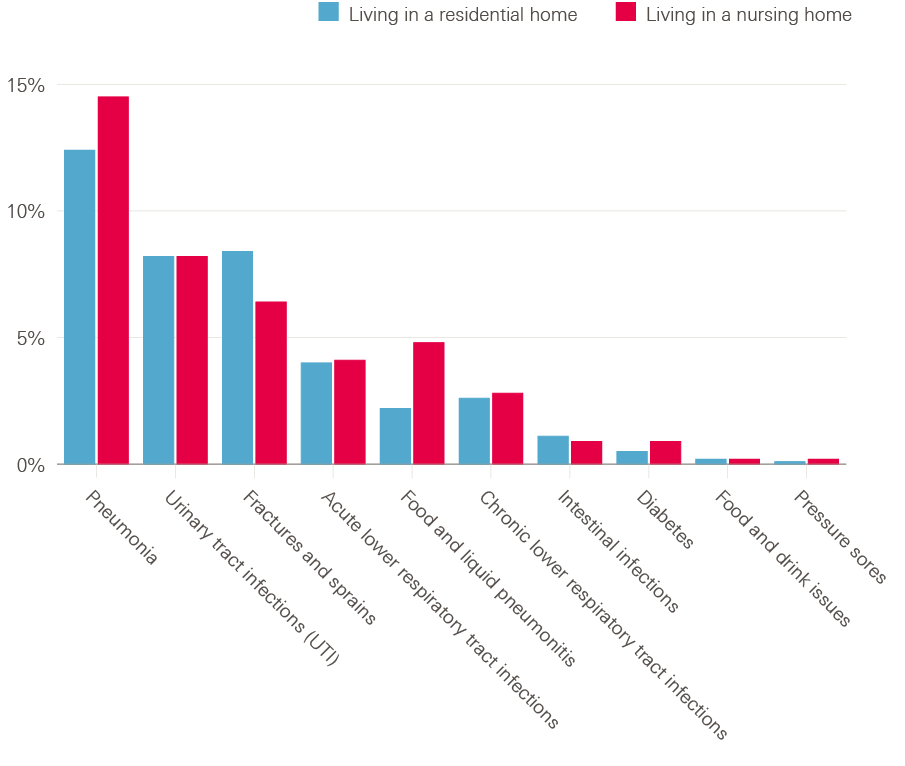

We estimated that residential care home residents had on average 0.30 potentially avoidable admissions per person per year; this equated to about 39% of all their emergency admissions. The most common potentially avoidable causes were pneumonia (12% of all emergency admissions), urinary tract infections (8%) and fractures and sprains (8%) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

In nursing homes, residents had on average 0.27 potentially avoidable admissions per year. This was equivalent to 43% of all their emergency admissions per person. The most common potentially avoidable causes were again pneumonia (15%), urinary tract infections (8%) and fractures and sprains (6%). There were more admissions from nursing homes for food and liquid pneumonitis than in residential care homes (5% vs 2%) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

However, these figures must be interpreted carefully. The reasons for admission to hospital for care home residents are often complex. Not all emergency admissions for these conditions will be avoidable. There may also be other conditions not in our definition of potentially avoidable admissions that were avoidable. We found that residential care home residents had on average a smaller proportion of potentially avoidable admissions than nursing home residents (39% vs 43%), but this was driven by the larger overall rates of emergency admissions in residential care homes (rather than lower rates of potentially avoidable admissions), indicating that there may be other admissions that could have been avoided.

Figure 1: Potentially avoidable emergency admissions for residential and nursing home residents aged 65 years or older in England, by reason for admission (% of all emergency admissions)

Note: Number of emergency admissions are rounded to the nearest hundred as they are estimates based on the correction applied to the data.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

How long do residential and nursing home residents spend in hospital once admitted?

Our analysis shows that once admitted as an emergency, care home residents aged 65 or older on average spend 8.2 days in hospital. This is similar to the amount of time that people aged 65 or older in general spend in hospital once admitted, which is 8.4 days on average. This means that 7.7% of emergency hospital bed days are occupied by care home residents even though they only make up 2.8% of the population aged 65 or older.

There is, however, some variability between care home types, with residential care home residents spending on average 8.9 days in hospital when admitted to hospital, and nursing home residents spending on average 7.4 days.

Hospital admissions resulting in death

When care home residents are admitted to hospital as an emergency, the admission concludes in death in 12% of cases (Table 3). Given that many care home residents are nearing the end of their life and that they often prefer to die at home,, some of these residents may have benefitted from not being admitted and instead being allowed to die in the care home. The percentage of emergency admissions that resulted in death were similar between residential and nursing home residents (12% and 13% respectively).

Of the admissions for those conditions that are potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside of a hospital setting, about 15% of admissions concluded in death in the hospital; this was similar across residential and nursing homes (15% vs 16%; Table 3). Of these admissions, those for food and liquid pneumonitis most often resulted in death in hospital, with 36% for residential care home residents and 29% for nursing home residents. Admissions for pneumonia resulted in death in hospital in 24% and 26% of cases respectively.

How do these patterns of hospital use vary by age within care homes?

Table 4 provides a breakdown of A&E attendances by care home residents by age bands (65-74, 75-84, 85+). It shows that were no substantial differences between age groups in rates of A&E attendances, percentage of A&E attendances leading to admission, rates of emergency admission and potentially avoidable emergency admissions.

The percentage of emergency admissions resulting in death slightly increased with age, with 9% of emergency admissions for residents aged 65 to 74, 11% for residents aged 75 to 84, and 13% for residents aged 85 or older. However, this is likely to reflect higher rates of death in general in the older groups.

The opposite trend can be seen in the average number of days spent in hospital, with length of stay decreasing slightly with age: residents aged 85 or older spend on average 7.8 days in hospital once admitted, compared with 8.5 days for residents aged 75 to 84 and 9.2 days for residents aged 65 to 74.

Table 2: Emergency hospital use for residential and nursing home residents and general population aged 65 or older in England

|

Care home residents (aged 65 or older) |

General population aged 65 or older |

|||

|

Residential home |

Nursing home |

Total |

||

|

Average number of people at any one time‡‡ |

135,000 |

139,000 |

274,000 |

9,751,000 |

|

Total number of A&E attendances |

151,000 |

117,000 |

269,000 |

4,142,000 |

|

Average number of A&E attendances per person per year§§ |

1.12 |

0.85 |

0.98 |

0.43 |

|

Percentage of A&E attendances not resulting in an (emergency) admission to hospital (%) |

40% |

35% |

38% |

54% |

|

Total number of emergency admissions |

104,000 |

88,000 |

192,000 |

2,432,000 |

|

Average number of emergency admissions per person per year¶¶ |

0.77 |

0.63 |

0.70 |

0.25 |

|

Percentage of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable (%) |

39% |

43% |

41% |

27% |

|

Average number of emergency admissions per person per year that were potentially avoidable |

0.30 |

0.27 |

0.29 |

0.07 |

|

Percentage of emergency admissions ending in death (%) |

12% |

13% |

12% |

7% |

|

Average number of days spent in hospital once admitted as an emergency (standard deviation) |

8.9 (14.5) |

7.4 (12.4) |

8.2 (13.6) |

8.4 (14.0) |

Note: Number of residents, A&E attendances and emergency admissions are rounded to the nearest thousand as they are estimates based on the correction applied to the data.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

How do these patterns vary by level of socio-economic deprivation?

We grouped care homes according to the levels of socio-economic deprivation in their surrounding area. Care homes in the most deprived fifth of England were home to 47,000 older people in 2016/7 (17% of all care home residents), compared with 52,000 older people in the least deprived fifth of areas (19%). There were comparatively more residents in the middle three fifths (Table 5).

Rates of emergency admissions increased with increased levels of deprivation; for example, care home residents in the least deprived areas had on average 0.64 emergency admissions per person per year, compared with 0.81 per person per year in the most deprived fifth of England (Table 5).

Similarly, the rates of A&E attendances increased with increased levels of deprivation; for example, care home residents in the least deprived areas had on average 0.84 A&E attendances per person per year, compared with 1.19 per person per year in the most deprived fifth of England (Table 5). Conversely, the percentage of A&E attendances that resulted in emergency admission decreased with increased levels of deprivation: in the least deprived areas, 65% of A&E attendances resulted in admission, compared with 59% of A&E attendances in the most deprived areas. This indicated that deprived areas may have more inappropriate A&E attendances than less deprived areas.

Rates of potentially avoidable emergency admissions showed a similar trend, with slightly lower rates for care home residents in less deprived areas (0.26 vs 0.34 in the most deprived areas). However, the proportion of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable were more similar between areas (40% in the least deprived areas compared with 42% in the most deprived areas).

The average number of hospital bed days following an emergency admission ranged from 8.1 days in the least deprived areas to 8.4 in the most deprived areas.

These findings may suggest that people living in care homes in the poorest parts of England may receive lower quality care. However, the proportion of the emergency admissions that are potentially avoidable was similar at 42% in the most deprived areas, compared with 40% in the least deprived areas. Furthermore, we found that about 47% of the care home population in the most deprived areas had a diagnosis of dementia recorded in the previous three years, compared with 39% in the least deprived areas (results not shown). Similarly, 18% of care home residents in the most deprived areas had renal disease, compared with 15% in the least deprived areas (results not shown). Therefore, some of the disparity in emergency admissions may be due to higher levels of ill health in the care homes in the most deprived areas. This could be linked to differences in, for example, the availability of publicly funded care home beds and home-based support.

Table 3: Potentially avoidable emergency admissions that resulted in death in hospital for residential and nursing home residents aged 65 years or older in England, by reason for admission (% of emergency admissions for that condition)

|

% of admissions resulting in death in hospital |

|||

|

Type of care home resident |

|||

|

|

Residential |

Nursing |

All |

|

All emergency admissions |

12% |

13% |

12% |

|

‘Potentially avoidable’ conditions |

15% |

16% |

15% |

|

Pneumonia |

24% |

26% |

25% |

|

Urinary tract infections (UTI) |

8% |

8% |

8% |

|

Fractures and sprains |

9% |

6% |

8% |

|

Acute lower respiratory tract infections |

8% |

8% |

8% |

|

Food and liquid pneumonitis |

36% |

29% |

31% |

|

Chronic lower respiratory tract infections |

9% |

11% |

10% |

|

Intestinal infections |

8% |

8% |

8% |

|

Diabetes |

8% |

8% |

8% |

|

Food and drink issues |

7% |

6% |

6% |

|

Pressure sores |

15% |

12% |

13% |

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

Table 4: Emergency hospital use by residential and nursing home residents aged 65 or older in England, by age band

|

Care home residents |

||||

|

Age 65 to 74 |

Age 75 to 84 |

Age 85 or older |

Total (aged 65 or older) |

|

|

Average number of people at any one time*** |

32,000 |

82,000 |

160,000 |

274,000 |

|

Total number of A&E attendances |

32,000 |

83,000 |

154,000 |

269,000 |

|

Average number of A&E attendances per person per year††† |

0.97 |

1.02 |

0.97 |

0.98 |

|

Percentage of A&E attendances resulting in an (emergency) admission to hospital (%) |

61% |

62% |

62% |

62% |

|

Total number of emergency admissions |

23,000 |

59,000 |

110,000 |

192,000 |

|

Average number of emergency admissions per person per year‡‡‡ |

0.70 |

0.73 |

0.69 |

0.70 |

|

Percentage of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable (%) |

40% |

41% |

41% |

41% |

|

Average number of emergency admissions per person per year that were potentially avoidable |

0.28 |

0.30 |

0.28 |

0.29 |

|

Percentage of emergency admissions ending in death (%) |

9% |

11% |

13% |

12% |

|

Average number of days spent in hospital once admitted as an emergency (standard deviation) |

9.2 (18.2) |

8.5 (14.3) |

7.8 (12.0) |

8.2 (13.6) |

Note: Number of residents, A&E attendances and emergency admissions are rounded to the nearest thousand as they are estimates based on the correction applied to the data.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

Table 5: Emergency hospital use by residential and nursing home residents aged 65 or older, by level of socio-economic deprivation of the local area

|

Care home residents aged 65 or older |

||||||

|

Most deprived fifth |

Second most deprived fifth |

Middle fifth |

Second least deprived fifth |

Least deprived fifth |

All care home residents |

|

|

Average number of people at any one time§§§ |

47,000 (17%) |

54,000 (20%) |

60,000 (22%) |

61,000 (22%) |

52,000 (19%) |

274,000 |

|

Number of care homes in this group |

2,900 |

3,400 |

3,700 |

3,200 |

2,500 |

15,800 |

|

Total number of A&E attendances |

55,000 |

59,000 |

56,000 |

55,000 |

44,000 |

269,000 |

|

Average number of A&E attendances per person per year¶¶¶ |

1.19 |

1.09 |

0.93 |

0.90 |

0.84 |

0.98 |

|

Percentage of A&E attendances resulting in an (emergency) admission to hospital (%) |

59% |

61% |

63% |

63% |

65% |

62% |

|

Total number of emergency admissions |

37,000 |

41,000 |

40,000 |

40,000 |

33,000 |

192,000 |

|

Average number of emergency admissions per person per year**** |

0.81 |

0.76 |

0.67 |

0.65 |

0.64 |

0.70 |

|

Number of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable (%) |

16,000 (42%) |

17,000 (42%) |

17,000 (41%) |

16,000 (41%) |

13,000 (40%) |

79,000 (41%) |

|

Average number of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable attendances per person per year |

0.34 |

0.32 |

0.27 |

0.27 |

0.26 |

0.29 |

|

Average number of days spent in hospital once admitted as an emergency (standard deviation) |

8.4 (14.2) |

8.3 (14.1) |

8.0 (13.4) |

8.2 (13.1) |

8.1 (13.3) |

8.2 (13.6) |

Note: Number of residents, A&E attendances and emergency admissions are rounded to the nearest thousand and number of care homes to the nearest hundred as they are estimates based on the correction applied to the data.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

Review of four case studies

The IAU has to date evaluated four initiatives to improve health and care in care homes: Principia enhanced support in Rushcliffe, enhanced support for Sutton Homes of Care, Wakefield Enhanced Health in Care Homes and Nottingham City enhanced package. A summary of the findings from the IAU studies of the four care home interventions related to A&E attendances, emergency admissions and potentially avoidable admissions are included in Box 2; for a full description of the intervention and evaluation please refer to the individual reports,,,,.

For several of the IAU studies we concluded there were reductions in at least some measures of emergency hospital use for residents who received the enhanced support, compared with their comparison groups: in Rushcliffe we found care home residents were admitted to hospital as an emergency 23% less often and had 29% fewer A&E attendances; Nottingham City care home residents had 18% fewer emergency admissions and 27% fewer potentially avoidable admissions; and in Wakefield residents had 27% fewer potentially avoidable emergency admissions. In Sutton, however, the results were inconclusive across all three measures of emergency hospital use.

There were many common themes across the four initiatives, however each site differed in what they implemented and how. By comparing the four IAU studies we aimed to identify themes that may point towards the successful implementation of the improvement programmes. Although it was not possible to unequivocally identify any elements of the improvement programmes that were particularly important for a successful intervention, we did identify some elements that may be driving the results.

Access to additional clinical input

What Rushcliffe and Nottingham City (the sites that had lower rates of overall emergency admissions compared with their control groups) had in common was the aim of having an aligned general practice for each care home and within each one a consistent named GP who regularly visited the care home (weekly, fortnightly or monthly). However this was not achieved in Nottingham City. Principia estimated that about 90% of residents were registered with the aligned GP in Rushcliffe. In Nottingham City, we estimated that about 79% of residential care home residents and 76% of nursing home residents in the study had an aligned GP (in other words were registered with the most common general practice within that care home) during the period of the study. Nottingham City CCG discontinued the GP Local Enhanced Service for Care Homes in June 2018.

In Wakefield, where the IAU study found lower rates of potentially avoidable emergency admissions but no difference in overall emergency admissions, the vanguard set out to implement GP alignment, however this was not achieved during the period of the study. Additional clinical input was provided through multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) comprising of professionals from areas including mental health, physiotherapy and nursing. The MDTs used a screening process to identify care needs that could lead to inappropriate emergency hospital use if not addressed, which may explain why the vanguard residents had fewer potentially avoidable emergency admissions than the matched control group.

Partnership and co-production

The level of co-production – in terms of joint working between health and social care providers and commissioners – may also have been an important aspect.

Nottingham City Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) first introduced initiatives to improve health outcomes among care home residents in 2007 and these have steadily grown over time and reportedly resulted in more active interaction between commissioners and health services. Nottingham City CCG and Nottingham City Council have a joint contract in place with care homes, with a shared service specification and quality framework, with work in this area first put in place in 2011.

In Rushcliffe, the enhanced support was developed by Principia, a local partnership of general practitioners, patients and community services, together with care home managers and the Rushcliffe CCG lead. The Principia enhanced support in Rushcliffe had a long-standing programme of work to build relationships across organisational boundaries, engaging care home teams. It is possible that this has led to greater mutual understanding of the nature of the problems that need to be addressed and, therefore, more effective interventions. There was a strong focus on building good relationships and partnership working between the members of the team. Furthermore, there were regular meetings between care providers working in different settings, which promoted shared ownership and a consistent approach. These included a monthly task group meeting between representatives of all members of the team and a bi-monthly care home managers’ network, facilitated by Age UK.

Although we did not see any conclusive evidence of the effect on emergency hospital use in Sutton, it also had partnership working. In May 2014, it established a Joint Intelligence Group, consisting of representatives from all partners across the health sector with a statutory responsibility for care homes, which met monthly to share intelligence across health and social care and promote quality assurance and safety.

Difference in effect in residential and nursing homes

Both the Rushcliffe and Nottingham City studies found that the positive results were driven by significantly lower rates of emergency hospital use in the residential care homes receiving the intervention, compared with their matched control groups, while there was no conclusive evidence in either site’s nursing home subgroup.

In Sutton, the data was in general inconclusive, which is not surprising given the small sample sizes within the subgroups (77 intervention and 76 matched control residents in the residential care home group and 220 in the intervention and matched control groups in nursing homes). In Wakefield, it was not possible to do a subgroup analysis on care home type as 84% of residents in the study lived in nursing homes. It may be that the higher proportion of nursing home residents in Wakefield (84%) and Sutton (74%) made it more difficult to see an effect (compared with 48% in Nottingham City and 64% in Rushcliffe).

However, the promising results in potentially avoidable admissions in Wakefield show that it may still be possible to improve care in nursing homes, but that potentially it requires care that is more targeted to individual residents’ needs, for example through the MDTs.

Maturity of the intervention and length of the study period

Both the Rushcliffe and Nottingham City set of interventions had developed and had time to mature by the time the study started. In Wakefield, the evaluation started from the beginning of the implementation. In Sutton, not all parts were implemented by the start of the study. This is likely to have impacted on our ability to find a significant effect of the intervention in Wakefield and in particular Sutton.

Furthermore, in Rushcliffe and Nottingham City, the study period was notably longer than in Sutton and Wakefield. The outcomes in Rushcliffe were analysed over a period of 23 months and in Nottingham City the study period was 2 years and 7 months, compared with Sutton and Wakefield where the study period was 15 and 13 months respectively. This will have allowed more time for the intervention to impact on residents’ use of health care and for the study to identify a significant change.

A subgroup analysis in Wakefield, only including residents who were in the study for at least 3 months, showed a larger reduction in potentially avoidable admissions compared with the main analysis, indicating that the impact of the intervention may differ as the intervention matures and as residents have more opportunity to be impacted by the changes in the care provided.

Training

There was a strong element of care home staff training, in particular in Rushcliffe and Wakefield, where training was delivered by either community nurses or the MDT on many topics, including falls prevention and pressure sore prevention. In Nottingham City, the Dementia Outreach Team provided staff training focusing on dementia. In Sutton, tailored e-training on continence care, dementia care and person-centred thinking was delivered to care home staff, as well as some ad-hoc face-to-face training delivered by the multidisciplinary care home team when it identified a need. However there were some challenges with training implementation.

Source: analysis by the Improvement Analytics Unit

¶ 8,000 residents lived in both a residential and a nursing care home in 2016/17.

** Socio-economic deprivation quintile is estimated based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015, available at Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) level. The LSOA is derived from the postcode of the care home where the patient is residing.

†† Health conditions, including the Charlson Index and Elixhauser list of comorbidities, are calculated on the subset of residents who had a hospital admission (emergency or elective) in the three years prior to the study. We estimated that 22% of residents at any time did not have a hospital admission during that period.

‡‡ The number of people living in care homes varies from month to month. These figures are averages across all months in the 2016/17 year.

§§ Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

¶¶ Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

*** The number of people living in care homes varies from month to month. These figures are averages across all months in the 2016/17 year.

††† Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

‡‡‡ Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

§§§ The number of people living in care homes varies from month to month. These figures are averages across all months in the 2016/17 year.

¶¶¶ Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

**** Allows for not all individuals being in the care home for the entirety of the 2016/17 year.

Discussion of results and implications

It has been a central aim of health policy in England for more than a decade to reduce demand for emergency care by making improvements to others part of the health care system. Earlier intervention and treatment has the potential to prevent emergency hospital use. One area where there has been a recognition of the need for improvement has been care in care homes with, for example, the Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) framework within the NHS’s New Care Models. The NHS recently published its 10-year Long Term Plan, which commits to improving NHS support to all care homes, including the roll-out of the EHCH framework, showing that there is a continued commitment to improve health and care in care homes.

Although there have been many evaluations of the EHCH vanguards, these have been of variable scope. Aggregate figures of EHCH vanguards indicate that participating care homes had lower emergency admission rates than non-vanguard areas. However, there is variation within this cohort, and therefore a need to identify which elements of the interventions can reduce emergency admissions, for whom and in which contexts.

What is the national picture?

This briefing presents the findings of a national analysis of care home residents’ emergency hospital use, using a novel and reliable method of identifying care home residents from administrative data.

Our analysis found that, in 2016/17, care home residents attended A&E on average 0.98 times per person per year and were admitted to hospital as an emergency 0.70 times for every year they were living in the care home. Although only 2.8% of older people live in a care home, they account for 7.9% of all emergency admissions in England for older people. Although emergency hospital admissions are often essential for delivering medical care, they can expose a patient to stress, loss of independence and risk of infection, reducing a patient’s health and wellbeing after leaving hospital. There are indications that a large number of these emergency admissions may be avoidable, with 41% of emergency admissions relating to conditions that are ‘potentially avoidable’, that is potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside of a hospital setting, or that could be caused by poor care or neglect. This does not mean that there was no medical need to admit a resident at the time of the admission, but rather that better care at an earlier stage of the care pathway may have prevented the admission. Common reasons for admission from care homes were pneumonia (13% of admissions), urinary tract infections (8%) and fractures and sprains (8%) (Figure 1).

Our analysis also found that residential and nursing homes, often considered together under the umbrella term ‘care homes’, differ, with residential care home residents having higher rates of emergency hospital use, even though one would expect them to be less severely ill than nursing home residents. For example, residential care home residents had on average 1.12 A&E attendances and 0.77 emergency admissions per person per year; nursing homes in contrast had 0.85 A&E attendances and 0.63 emergency admissions per person per year. Over the whole year, this equated to residential care home residents having on average 32% more A&E attendances and 22% more emergency admissions than nursing home residents. Residential care home residents on average also stayed in hospital slightly longer than nursing home residents (8.9 vs 7.4 days).

The finding that residential care home residents have higher hospital use than nursing homes is an important one pointing towards unmet needs in residential care homes, which is, to our knowledge, not widely known. During our literature search, we found only one reference to higher emergency admissions and one to higher ambulance call-outs in residential versus nursing homes.

What can the NHS and social care do to reduce emergency admissions from care homes?

As NHS England and local teams look to implement the EHCH framework in care homes, insights are needed in order to identify which elements of the interventions can reduce emergency admissions, for whom and in which contexts. The IAU has to date evaluated four initiatives to improve health and care in care homes that were either EHCH vanguards or similar initiatives. By comparing the four IAU studies, we aimed to identify themes that may point towards the successful implementation of the improvement programmes.

It was difficult to identify such themes as there was a combination of elements set within complex contexts. Furthermore, there were differences between the studies that were not related to the intervention. Although it is not possible to unequivocally identify any elements of the improvement programmes that were particularly important for a successful intervention, we propose some elements that may be driving the results.

One key success criteria may be the extent to which a genuine partnership, based on shared objectives and approaches, is fostered between health and social care providers. Several studies have pointed towards both the importance of care home and NHS staff working together as partners, to co-design and implement concerted approaches to health care, and acknowledging care home staff’s knowledge and skills.

Another element common to Rushcliffe and Nottingham City, where the initiatives were associated with fewer overall emergency admissions, was the aim of having an aligned general practice for each care home and within each one a consistent named GP who regularly visited the care home. This may have had many benefits: firstly, the continuity of care enables a personal relationship with the resident to develop, which allows the GP to know the resident’s medical history and wishes, and potentially also identify subtle changes in their health so that these can be addressed early. Secondly, closer working relationships between care home staff and the GP may have enabled care home staff to feel able to raise concerns or ask questions regarding their residents’ care; and the more regular visits may have led to care home staff feeling more confident to proactively manage health risks, thereby reducing their reliance on emergency services. Thirdly, having multiple different GPs visiting the care home may be disruptive to staff.

In Wakefield, although the vanguard set out to implement GP alignment, this was not achieved during the period of the study. All GPs in Wakefield, not just the ones affiliated with the vanguard, already visited their care home patients when required even before the vanguard started, and continued to do so. There were therefore limited differences in GP care between the vanguard care homes and non-vanguard care homes in the CCG. However, Wakefield implemented MDTs comprising professionals from areas including mental health, physiotherapy and nursing, who proactively planned and managed care for residents who needed additional support. The MDTs used a screening process to identify care needs that could lead to inappropriate emergency hospital use if not addressed. This may therefore explain why we found lower rates of potentially avoidable emergency admissions in Wakefield intervention residents.

Our work shows it is important to consider the differences between nursing and residential care homes, and the difference in impact enhanced care packages may have on residents. The results seen in our studies of the impact of the enhanced care provided in Rushcliffe and Nottingham City were driven by the residential care homes, with potentially large effects in these homes but no conclusive evidence of a difference in hospital use in nursing homes. It may be that there are unmet needs in residential care homes and that the additional support from GPs and other health professionals may increase the care home staff’s ability to proactively manage health risks and reduce their reliance on emergency services., Combined with the evidence from our national analysis showing that residential home residents have higher rates of A&E attendances and emergency admission than nursing home residents, you could conclude there is therefore greater potential to reduce A&E attendances and emergency admissions among residents in residential homes than in nursing homes when implementing initiatives such as these. However, the lower rates of potentially avoidable admissions in Wakefield vanguard care homes, where the majority of residents (84%) lived in nursing homes, indicates that there is scope to reduce emergency hospital use in nursing homes, too. It may be that this was due to the more targeted approach of the Wakefield MDTs to identify and address specific residents’ care needs.

When implementing the EHCH framework more widely it is worth considering the differences between residential and nursing homes. It may be that no difference in outcomes for nursing home residents were found in Rushcliffe and Nottingham City because nursing homes in general receive more support from health professionals as part of 'standard care', compared with residential care home residents,,,,. This is possibly because nursing home residents are perceived as being at higher risk. A 2002 survey of 570 care homes found that 10% of care homes at the time had an aligned GP and that this was 20% in nursing homes. Although there has since been a drive to increase access potentially at the expense of continuity, this pattern may still be present. This theory is also consistent with the observation that more of the research on care homes relates to nursing homes. Another hypothesis is that nursing home residents in general have more health conditions such as cancer and chronic pulmonary disease and are more often at the end of life and therefore it may be less possible to affect their hospital use.

It could also be because it was more difficult to engage and create good relationships between health care professionals and care home staff in nursing homes. Nurses in nursing homes, who have clinical expertise, may feel more responsibility for their residents’ clinical health needs than other staff. This may require more emphasis on co-design and early engagement to create good working relationships and ensure that in-house nurses feel like partners.

One further observation from our review is that it is likely to take time for interventions to become fully operational and for them to lead to changes in emergency hospital use that are substantial enough to produce statistically significant results. Both Rushcliffe and Nottingham City had time to embed the interventions before the start of the study (the period of the study was 23 months and 2 years 7 months respectively). Although we also found evidence of impact on potentially avoidable admissions for care home residents in Wakefield, this effect was stronger looking at only those residents who had been resident in a care home for three months or longer. When no evidence of an impact is identified early on in a study it can still be useful to carry out evaluation in the early stages of an intervention to check for early signs of improvement, but it is important to view any results as preliminary evidence, and continue evaluation efforts on an iterative basis throughout the implementation of an intervention.

Accessing routine data on care home residents

In general there has been a dearth of reliable studies on care homes. Part of the problem has been the difficulty in identifying care home residents in administrative data. The IAU and two other teams have independently and in parallel developed methods to identify care home residents by matching patient addresses with care home addresses, but these data need to be routinely and consistently collected and easily accessible to both research teams and care providers if we are to understand residents’ health care needs, produce robust evaluations and ultimately improve care for this vulnerable patient group.

Conclusions

The NHS in England is already working with care homes to improve the care provided to residents, most notably through the roll-out of the Enhanced Health in Care Homes framework and ongoing efforts to foster greater integration between health and social care.

These initiatives will be helped by a better understanding of the quality of health care provided in care homes, for which emergency admissions, especially rates of potentially avoidable admission, can be seen as a proxy. Ongoing robust evaluation of local care home initiatives is needed to identify those schemes that are having a positive impact on emergency admissions and to identify the active ingredients driving improvement. Identifying and spreading the use of these active ingredients are likely to bring benefits to people living in care homes and to the wider NHS.

Our analysis of national rates of emergency care found that 7.9% of the total number of emergency admissions for older people in England are for care home residents. This shows that reducing emergency admissions from care homes has the potential to reduce pressure on hospitals.

Furthermore, our evaluations of four care home initiatives show that there is potential for the roll-out of the EHCH framework to benefit individuals and reduce demand for emergency hospital use, and provide some hypotheses regarding how best to do so.

In particular, we found that there is potential to reduce A&E attendances and emergency hospital admissions in residential care homes. Both the national analysis and the evaluations point towards residential care home residents having unmet needs and that an improvement programme such as the EHCH framework has significant scope to improve their care and outcomes. This review therefore suggests that nationally we should perhaps re-evaluate the perceived risk and clinical support needs of residential care home residents.

This does not mean that there is not scope for improvement in nursing homes too, especially as there are aspects to quality of care in addition to reducing emergency hospital admissions, such as quality of life. It may be that ‘usual care’ in nursing homes already encompasses some of the elements of the enhanced support, making further reductions in overall emergency hospital admissions more challenging. However, our evaluation of Wakefield indicated that there is potential to reduce emergency hospital admissions related to specific conditions that are potentially manageable, treatable or preventable outside of a hospital setting. Therefore, a more targeted approach, for example including regular reviews of residents’ hospital admissions to help identify and track reasons for unnecessary A&E attendances and emergency hospital admissions along with residents of particular concern, may be required.,, To be able do this effectively, staff caring for residents need access to these data as an important step towards further improving care. Furthermore, although good working relationships between health care professionals and care home staff are important for the successful implementation of improvement programmes in both types of care home, more engagement and greater focus on establishing good working relationships may be required in nursing homes.