Foreword

The pursuit of safety is not for the timid. This Health Foundation report eloquently surveys the landscape of obstacles. But there are at least two inescapable facts that make improving safety especially difficult and frustrating.

First, securing safety is a task that cannot be ‘finished’, ever. As Professor James Reason puts it: ‘Safety is a continually emerging property of a complex system.’ The threats to safety flow like an endless game on a football field, in which no two patterns and no two moments are ever the same. Linear thinking – the search for simple, single causes – is doomed. All modern approaches to achieving safety (or reliability, for that matter) require continual attention to adjustments, resilience, adaptation and local contexts.

It is so tempting, especially in politicised contexts, to try for simple answers, to ‘plug in’ safety like one plugs in a toaster. Certainly, there are techniques that can help. Checklists, monitoring devices, transparent metrics, standardised processes – these and many other mechanics have proven their worth in the right context at the right time. But, fundamentally, the quest for the installable ‘fix’ is doomed. The most important cultural characteristic of the safest enterprises is not that they have the right technical features in place (although they should), but rather that they are full of people at all levels who can sense, change, adapt and change again in response to the ever-changing terrain of threat and challenge – and are supported by their leaders to do so. Indeed, in that sense, safer systems are safer because they are never the same twice. That’s what James Reason means by ‘a continually emerging property’.

Second, the pursuit of safety depends on volunteerism. It is more about what people choose to do than about what they are required to do. Safety cannot, in any meaningful sense, be required of a workforce or, for that matter, of those they serve. For leaders, this means that their job is continually to try to build on and support intrinsic motivation.

For understandable reasons, the temptation to depend on rules and requirements is seductive. For one thing, it’s a lot easier. For another, organisations and societies obviously do need rules. We don’t want roads without speed limits, electrical plugs without grounding, or mains water with harmful germs. But René Amalberti et al emphasise the importance of distinguishing between (and acting differently on) ‘extreme violations’ (which are rare and intolerable) and ‘borderline tolerated conditions of use’ (which are pervasive, inevitable, and often wise and informative violations of rules).

Similarly, Karl Weick has clearly elucidated the properties of very safe, ‘high reliability organisations’ (HROs), and strongly emphasises the crucial capacity of ‘sensemaking’ in achieving their results. Understanding and honouring these behavioural and cultural elements of what I might call ‘deep’ safety – as opposed to ‘compliant’ safety or ‘looking good’ safety – demands a level of maturity and psychological sophistication that are too often simply not in the repertoire of an organisation, a leadership system, or a political economy.

It is for this reason that the National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England, which it was my honour to chair, determined that culture will trump rules. That is not a soft idea; it is one grounded in evidence and safety science.

This report from the Health Foundation could be a landmark. Carefully studied and thoroughly acted on, it could mark a shift in the maturity of the safety movement, at least in the UK. It could signal a change from a movement that has been, with all good intention, too tethered to rules and requirements as the anchors for patient safety, to one far better informed by the scientific insights of Amalberti, Reason, Weick, Vincent and others who have been trying to teach us to eschew simple mechanics and embrace the pursuit of safety in all its subtle but nonetheless powerful human dimensions.

Above all else, the key lesson seems to be this: seeking safety raises the question ‘How do we want to be?’ far more emphatically than the question ‘What do we want to require?’ A rule-bound organisation cannot be truly safe. That requires things more important than rules: things like maturity, curiosity, dialogue, daylight, reflection, teamwork, hope and trust. It’s a tougher job for leaders than simply writing and enforcing rules. The difference is, it works.

Donald M. Berwick, MD

President Emeritus and Senior Fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Executive summary

This report makes the case for changing the way patient safety is approached in the NHS. It argues that change is needed in: how safety is understood, because current approaches to measurement don’t provide the full picture; how safety is improved, because existing approaches alone will not address the most intractable problems; how risk is perceived, because comfort-seeking behaviours will not create a genuine culture of learning.

The patient safety movement is now at a critical moment; to sustain momentum, there has to be recognition that things can – and should – be better.

There have been some remarkable successes in recent years to improve patient safety and tackle harm, and front-line teams supported by the Health Foundation have been an important part of these efforts (see pages 6-7 for examples of some of our current work). This report brings together what we have learned from this work, and also highlights some salutary lessons about the state of patient safety in the NHS and the complex task of continually trying to improve it.

We have learned that many systems are not designed with safety in mind, meaning that it is only the skill and resilience of health care professionals that prevents many more episodes of harm. We have learned that many care processes are unreliable, which can mean that the right equipment isn’t available in theatre, or the wrong drug is given to a patient. We have learned that many institutions don’t have a complete picture of safety, because they focus largely on past events rather than current or future risks. We have learned that there are some common factors that have repeatedly contributed to large-scale failings, but that these factors have consistently not been addressed.

Despite the many successful quality improvement projects the Health Foundation has supported, there have been many more that haven’t delivered the expected benefits. We are only now coming to fully understand the reasons for this. For instance, front-line teams consistently come up against ‘big and hairy’ issues such as inadequate information technology, inconsistent staffing and challenging established cultures. Yet these issues are far beyond the scope of individual teams, and the scope of quality improvement methods alone, to address. If the most intractable safety problems require nationally coordinated solutions, then existing approaches will not yield the future gains that patients and the public expect.

So what might safer care look like in the future?

In our view, a safer care system is conceived from the perspective of the patient, following his or her journey through different care settings, irrespective of organisational boundaries. It is networked, so that successes and failures identified in one part of the system can be readily accessed, understood and built on in another. And it is judged not by the prevalence of adverse events, but by the ability to proactively identify hazards and risks before they harm patients.

How can we get there?

- The journey must begin with practical improvements, based on what is known to work. This report presents a checklist for safety improvement, based on our experience of supporting NHS teams to improve safety. The checklist should be used by front-line teams and organisations when addressing their most pressing safety problems. (See page 28.)

- Improvements to safety on the ground can only be successful with the support of senior leaders in provider organisations. This report sets out the three vital steps that senior leaders should take to create an environment where safety improvement can flourish. (See page 29.)

- The practice and policy of safety improvement are inextricably linked, reflecting recognition that the design of the wider system can support, and hinder, the efforts of front-line staff and senior leaders. This report sets out our vision for an effective system for safety improvement. (See page 34.)

Underpinning everything is the need to approach the work with trust, sincerity and openness. Local improvements in safety won’t be successful if they are not applied faithfully, just as national improvements in safety won’t be achieved if they become subverted into measures of accountability. These are the core lessons we have learned over the past decade; this report draws on them to make the case for why and how future improvements in safety can be realised.

Health Foundation patient safety projects in 2015

This map shows the patient safety projects that the Health Foundation has supported in 2015.

For more details about the ful range of the Foundation's past and present work on patient safety, please visit: www.health.org.uk/theme/patient-safety

Introduction

Over the past decade, the Health Foundation has supported and funded thousands of people working in different settings, from hospitals to care homes, to develop and test approaches to making care safer. We have learned about some of the specific causes of harm, and which problems can be addressed by front-line teams using quality improvement methods. The many successes should be cause for celebration. They have played their part in dramatically reducing the number of patients harmed by safety problems. However, there is also cause for impatience. We still do not really understand why even highly successful projects do not spread at the speed many would expect; and solutions to the bigger, system-wide challenges remain few and far between.

This report synthesises the lessons from the Health Foundation’s work on improving patient safety over the past decade. Part I illustrates why improving safety is so difficult and complex, and why current approaches need to change. Part II looks at some of the work being done to improve safety and offers examples and insights to support practical improvements in patient safety. In Part III, the report explains why the system needs to think differently about safety, giving policymakers an insight into how their actions can create an environment where continuous safety improvement will flourish, as well as how they can help to tackle system-wide problems that hinder local improvement.

The report includes specific resources that we hope will contribute to the next phase of safety improvement in the NHS:

- For people improving safety at the front line, we provide a checklist for safety improvement to be used when developing solutions to safety problems. This checklist is based on our experience of supporting NHS teams to improve safety over the past decade. (See page 28.)

- For leaders of provider organisations, we set out three practical steps that need to be taken to build an organisation-wide approach to continually improving safety. (See page 29.)

- For government, quality regulators and national bodies with a remit for patient safety, we set out our vision for an effective safety system, which current activities and ambitions should be assessed against. This vision is based on what we have learned about the barriers to safety improvement, and what we consider to be the future frontiers for safety in health care. (See page 34.)

The report also includes a series of viewpoints from leading figures in safety improvement, answering the question ‘What is the future of patient safety?’ from their perspective.

Part I: The case for change

Learning from major safety failings

Health care is a hazardous business. It brings together sick patients, complex systems, fallible professionals and advanced technology. It is classed as a ‘safety-critical industry’, where errors or design failures can lead to the loss of life. Terrible recent care failings illustrate the reality of these hazards, and the significant challenges involved in trying to address them. As with other safety-critical industries, it is imperative that when failures do occur, lessons are learned and action is taken to prevent the same issues reoccurring. As to whether or not this is happening, history tells a different story.

Take the following list of factors, identified in the 2001 Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry into the deaths of babies undergoing heart surgery:

- Isolation – in organisational or geographic terms, leaving professionals behind developments elsewhere, unaware or suspicious of new ideas, with no exposure to constructive critical exchange and peer review.

- Inadequate leadership – by managers or clinicians, characterised by a lack of vision, an inability to develop shared or common objectives, a weak or bullying management style, and a reluctance to tackle problems even in the face of extensive evidence.

- System and process failure – where a series of organisational systems and processes were either not present or not working properly, and the checks and balances needed to prevent problems were absent.

- Poor communication – affecting both communication in the health care organisation and between health care professionals and service users, where stakeholders knew something of the problems subsequently identified by an inquiry, but emergence of the full picture in a way that would prompt action was inhibited.

- Disempowerment of staff and service users – where those who might have raised problems or concerns were discouraged from doing so, either because of a sense of helplessness in the face of organisational dysfunction or because the prevailing organisational culture precluded such actions.

The same factors had been cited some 30 years earlier, in the 1969 Ely Hospital Inquiry into long-stay care for older people and people with mental health problems.

The factors are systemic, cultural, contextual and human in nature, and elements of all of them were also identified in the inquiries into failings of care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and, most recently, Morecambe Bay, some 46 years after the Ely Hospital Inquiry. While such factors are complex, multifaceted and difficult to eradicate, their persistence across the decades is cause for serious concern.

Viewpoint: What is the future of patient safety?

Learning from failure, by Martin Bromiley

Martin is Chair of the Clinical Human Factors Group and an airline pilot.

When you work in or observe a safety-critical industry, safety isn’t an extra. ‘Safety’ or ‘quality’ are rare words because these things are already part of the day-to-day conscious and subconscious thoughts and behaviours of everyone. The system is designed, refined, observed, questioned and challenged to make it easy to do things right.

Ironically, the successful industries accept failure as inevitable. When little problems occur with no adverse outcome, they’re seen as big problems. Failure is seen as the path to robustness and resilience. Just as an elite sports person constantly makes small changes, the ‘aggregation of small gains’ applies to industry. Sports people don’t ‘beat themselves up’ about failure; they learn from it. In the same way, clever industries don’t beat up individuals; learning and blaming are two different things.

Learning from failure should be a thoughtful and coordinated process led by people who make sure best practice becomes the norm across the whole business.

And to what end? To minimise variability of outcome – which is what any industry (or individual) in a high-risk pursuit fears. Variability, whether measured by loss of life or money, is becoming increasingly unacceptable in society. Human beings are remarkably variable in their output. Their non-linear thought processes create adaptability and remarkable ‘saves’, but heroic saves are often the result of a system found wanting. Only a system that makes it easy for humans to do things right is consistent, efficient and safe.

Why is it so difficult to improve safety?

The complex range of factors identified in major care failings also play a central role in the success (or failure) of efforts to improve safety. In 2004, the Health Foundation launched the Safer Patients Initiative – the first major improvement programme to address patient safety in the UK. The programme ultimately helped to raise awareness of the problem of avoidable harm and provide a basis for a wider safety movement. It also began a journey which has deepened our understanding of why improvement programmes often fail to achieve the desired impact. So just why is it so difficult to improve safety? Four key reasons are: complexity, connectedness, context and counting.

Complexity: local improvement interventions cannot solve organisation-wide safety problems

The Safer Patients Initiative focused on improving the reliability of care within four clinical areas across 24 hospitals. A range of improvement interventions were used to tackle problems ranging from central line bloodstream infections to ventilator-associated pneumonia. The aims were a 30% reduction in adverse events and a 15% reduction in mortality, as well as specific goals relating to a range of process and outcome measures.

The independent evaluation of the initiative showed that all sites had improved on at least half of the 43 measures chosen. But many comparison sites that were not participating in the initiative were also improving at the same time owing to a ‘rising tide’, including many concurrent national policy initiatives. The evaluation also showed that the programme failed to become embedded into wider structures and processes, highlighting the scale of resources needed to bring about organisation-wide change.

Connectedness: deceptively simple safety problems often need system-wide solutions

The Safer Clinical Systems programme ran in two phases from 2008 to 2014. In the first phase, the Safer Clinical Systems approach was developed and tested. In the second phase, organisations were supported to try and create systems that were free from unacceptable risk in two areas – clinical handover and the management of medicines. Teams conducted systematic diagnostics on their clinical systems, collecting an array of evidence in order to make a ‘safety case’ about the safety of their service. On the basis of this, the teams chose interventions to address the risks.

Among other lessons, the independent evaluation found that many safety problems were outside the control of individual front-line teams to tackle. These problems often needed to be addressed at the organisation or system-wide level. They included inconsistent staffing, issues with information technology, or challenging established cultures. Although such problems aren’t new to those working in the health service, the evaluation highlighted the degree to which they are entrenched and can stand in the way of local improvement.

Context: the success of safety interventions depends as much on the context in which they are applied as on how well they are carried out

Many safety improvement efforts aim to replicate initiatives that have been successful in other contexts. The Lining Up research project evaluated efforts in England to reproduce the success of the Keystone programme in the US state of Michigan. Keystone had achieved dramatic reductions in bloodstream infections linked to central venous catheters (CVC-BSIs) in intensive care units. The English initiative, known as Matching Michigan, adopted the same interventions, which included technical components (such as the use of chlorhexidine to prepare the patient’s skin) and non-technical components (such as education on the science of safety).

The Lining Up team found that, even where the technical components of an initiative were applied well, a range of contextual factors, including the legacy of previous initiatives, influenced its success. This demonstrated that a programme transplanted from elsewhere does not always work in the same way in the new setting (see also Box 1 overleaf). The team concluded that a deep understanding of why a programme was successful, and how it must be adapted to the local needs and priorities on the ground, was essential.

Box 1: The importance of context: PROMPT (Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training)

Developed by Tim Draycott and colleagues at Southmead Hospital, PROMPT is a one-day multi-professional training course that uses sophisticated simulation models to address the clinical and behavioural skills required in obstetric emergencies. Since its introduction at Southmead in 2002, injuries to babies caused by a lack of oxygen have reduced by 50%, and injuries caused by babies’ shoulders becoming stuck during delivery have reduced by 70%. Work with the NHS Litigation Authority demonstrated that litigation claims at the trust have fallen by 91% since PROMPT was introduced.

The tool has since been adopted by 85% of UK maternity services and by units in many other countries. However, how to reliably reproduce the success of Southmead in new contexts has remained a key question. Led by Mary Dixon-Woods, a study is now underway to fully characterise and describe the mechanisms underlying the improvements.

Counting: assessing safety by what has happened in the past does not give a complete picture of safety now, or in future

The Lining Up research demonstrated that even the seemingly straightforward task of measuring improvements in safety varied so much as to make comparisons between sites ‘almost meaningless’. The challenges of safety measurement were further explored in a 2013 research report by Charles Vincent, Jane Carthey and Susan Burnett, The measurement and monitoring of safety. Their report brought together existing literature and findings of expert interviews and case studies of health care organisations already exploring innovative ways to measure safety. The researchers concluded that, despite the high volume of data collected on medical error and harm to patients, it was still not possible to know how safe care really is, and that assessing safety by what has happened in the past – such as by the number of reported incidents – does not tell us how safe care is now or will be in the near future.

Given the tendency to focus on measuring individual aspects of harm in the NHS, rather than system measures of safety, it is inevitable that an answer to the question of whether the NHS is getting safer remains ‘curiously elusive’.

The state of patient safety in the NHS

Harm caused by health care affects every health system in the world, and the NHS is no exception. Research from the UK and abroad has shown that people admitted to hospital have around a one in 10 chance of being harmed as a result of their care. About half of these episodes of harm are avoidable. We know far less about safety in settings outside of hospital, but research has suggested that around 1–2% of consultations in primary care are associated with an adverse event. The cost of harm – to patients, to those working in health care, and to productivity – is significant. However, creating a health care system that achieves zero avoidable harm is not a realistic ambition.

This is, in part, because understanding of harm – and the types of harm that are avoidable – continues to develop. Problems that were once seen as inevitable consequences of health care (such as some infections) are now seen as both preventable and unacceptable. Other problems, such as medication errors, which appeared in principle to be solvable, have turned out to be much more intractable. Further developments will give greater attention to the psychological aspects of harm, or the harm caused by failing to provide care in a timely way. However, these dimensions of safety are rarely captured through current reporting systems. Therefore, rather than zero avoidable harm, the appropriate ambition should be to continually reduce harm.

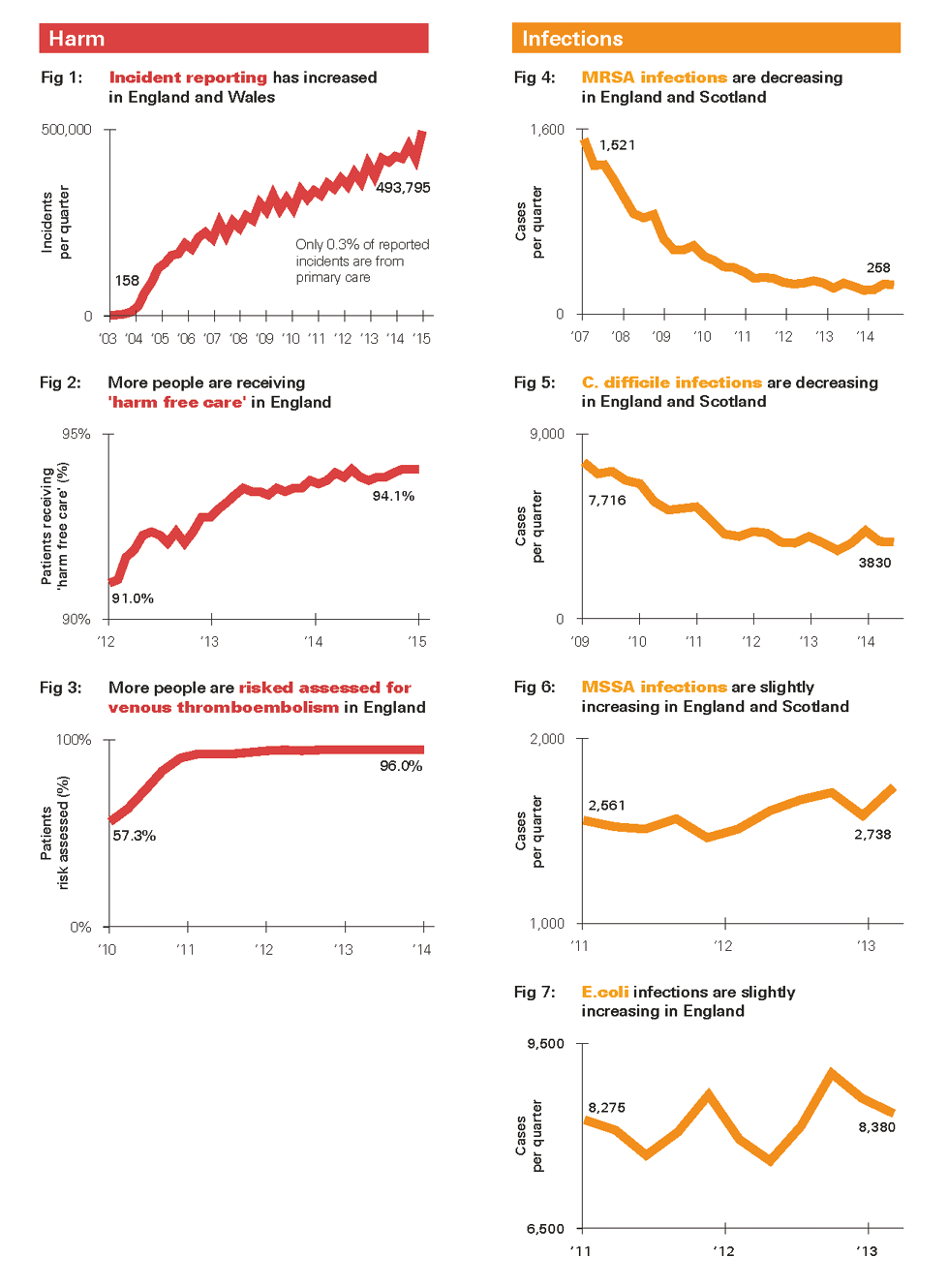

So how well is the NHS doing in continually reducing harm? Analysis of some of the measures available nationally shows that, despite some significant achievements, many gaps in knowledge remain. Even where there are measures available, the indicators paint a mixed picture (see Figures 1–13 overleaf). For example:

- People working in the NHS are increasingly willing to report safety incidents (Figure 1). However, just 0.3% of all reported incidents are in primary care, despite 90% of all patient contact taking place there. This suggests significant underreporting of harm in primary care, even taking into account the generally less risky interventions involved.

- There has been great progress in reducing rates of health care associated infections (HCAIs) such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile (Figures 4 and 5). However, rates of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and E. coli – which have drawn less political attention – have actually risen (Figures 6 and 7).

- People working in hospitals are more confident that action will be taken following an incident (Figure 8). However, more of them say their organisation has a blame culture (Figure 9).

- More people feel they would be safe if they were treated in hospital (Figure 11). But around 40% of patients feel there aren’t always enough members of staff on duty to care for them (Figure 12).

- In 2014, the Commonwealth Fund ranked the UK as first for safe care out of 11 developed nations. However, in 2014/15, the Care Quality Commission rated 61% of hospital trusts as ‘requires improvement’ and 13% as ‘inadequate’ for safety.

It is clear that things must continue to change. There needs to be recognition of the successes of the past, but also of the limitations of current approaches to improving safety – and the role that policymakers and national bodies can play in fostering improvement. These issues, together with examples of the practical experiences of front-line teams, are explored in parts II and III.

Figures 1-13: NHS performance on a range of patient safety indicators over time, across England, England and Scotland or England and Wales

* Safety cases are widely used in other safety-critical industries. They involve compiling a structured argument, supported by a body of evidence, to make the case that a system is acceptably safe for a given application in a given context. For more information about safety cases, and their use in health care and other industries, see www.health.org.uk/safetycasesreport

† In our recent report, Indicators of quality of care in general practices in England, we recommend that improving data and indicators in primary care should be a priority for the NHS in England.

‡ For more information see our briefing, Is the NHS getting safer?16

Part II: Safety improvement in practice

Over the past 10 years, the Health Foundation has worked with a wide variety of people, teams and organisations that have been trying to improve safety in health care in the UK. In this part, we draw out some of the key lessons from this work across four themes: measurement and monitoring; improvement and learning; engagement and culture; and strategy and accountability.

Measurement and monitoring

Effective measurement is central to understanding the quality of care being provided, and to supporting any efforts to improve care. As shown in Figure 14, the framework for measuring and monitoring safety developed by Charles Vincent and colleagues sets out five questions that any unit, team, service or organisation should ask to establish how safe their service is.

Figure 14: A framework for measuring and monitoring safety

In 2013, the Health Foundation tested the framework in three NHS providers in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Clinicians and managers at those providers told us that the vast majority of safety data they collected related to past instances of harm. In a survey we conducted with more than 200 NHS patient safety leads in England, more than a quarter of respondents told us that their organisation was not effective in being alert to emerging safety problems or anticipating future problems. While more traditional forms of safety measurement were common (for instance, four out of five respondents told us they had risk registers), only one in four said their organisation uses safety culture assessments or discusses safety risks regularly on handovers and ward rounds.

NHS organisations across a wide range of care settings and in different contexts have since begun adopting the principles of the framework, both as part of our funded programmes and on their own initiative (see Box 2).

Box 2: Using the framework for measuring and monitoring safety in health care

- North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust is using the framework to develop a range of safety indicators, including the number and type of vehicles requiring services or safety checks, to anticipate and prevent delayed response times. It has also introduced safety huddles in the Emergency Operations Centre to communicate critical information to the whole team.

- Senior leaders from across Greater Manchester, including provider boards, governing bodies of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and local authorities are coming together to develop a shared vision for safety and to improve safety surveillance across health economies. The Making Safety Visible programme is building leaders’ capability and changing approaches to the measurement and monitoring of safety across systems.

- East London NHS Foundation Trust’s efforts to improve the reliability of its services included a review of clinical audit, which led to a 70% reduction of standards being measured, as they were felt to add little value to quality and safety. The remaining standards were aligned to safety critical processes. In addition, the trust has developed whole-system measures of quality and safety to help the board understand whether the organisation is improving over time.

- The burns and plastic surgery team at Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust developed a web-based tool to give rapid feedback on patient outcomes. It uses risk-adjusted cumulative sum (CUSUM) charts to add up the times that certain positive or negative outcomes occur, enabling teams to respond rapidly to improve outcomes for patients in future, and to learn from periods of especially good outcomes.

The measurement framework does not recommend which measures to use, and it discounts the myth that a single measure of safety is possible. But it has a practical application for people working at different levels of the NHS to ultimately improve patient experience and public confidence more widely:

- For managers and front-line health professionals, the framework means reflecting on the usefulness of the data currently collected, which may lead to existing measures being discarded, as well as additional measures being introduced.

- For board members and senior executives, it means actively seeking information about hazards and risks to gain the fullest possible picture of safety.

- For government, regulators and national bodies, it means encouraging organisations to demonstrate how safe their services are by using their own measures as well as centrally mandated ones.

Adopting the framework also requires a shift in the type of data that are collected and the indicators that are reported as a result. The vast majority of safety data that are currently collected relate to past incidents of harm – known as ‘lagging indicators’. Such measures ought to remain a cornerstone of understanding patient safety, but they should be complemented by monitoring the conditions that can make harm more likely to occur – known as ‘leading indicators’. Leading indicators in health care remain sparse, but can include information gained from staff and patient surveys or safety culture assessments. This shift from lagging to leading indicators should also enable the NHS to move away from reacting to the latest care failing to actively demonstrating the safety of its services.

An approach to measuring and monitoring safety that covers all of the dimensions of the framework will better reflect the likely experience of patients today or tomorrow. It will provide a more accurate baseline against which the impact of improvement efforts can be measured. It will also provide the evidence on which areas of unsafe care can be identified, in order to target future improvement efforts. From this foundation, therefore, the full benefits of systematically improving safety can be realised.

Improvement and learning

Quality improvement methods are founded on scientific principles generally developed in other industries. These methods can provide front-line NHS teams with the tools to systematically address pressing safety problems. For example, participants in the Safer Clinical Systems programme used a range of quality improvement methods to address safety issues. However, before any improvement methods were deployed, the teams carefully documented the processes within their care pathways, and then used tools (such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis) to diagnose the hazards and risks within those pathways.

This process of diagnosis was illuminating for the teams, and is an important prerequisite to successfully implementing quality improvement methods. Research led by Mary Dixon-Woods has found that quality improvement methods can sometimes be used uncritically or indiscriminately, with some evidence of ‘magical thinking’ – assumptions that a method can solve problems quickly and easily. The research team also observed that front-line staff responsible for implementing quality improvement methods were often not consulted or properly informed about their purpose, which meant that some initiatives were abandoned shortly after their introduction.

Viewpoint: What is the future of patient safety?

Moving to a system-wide approach, by Professor Mary Dixon-Woods

Mary is Professor of Medical Sociology and Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator in the SAPPHIRE group, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester

Getting better at keeping patients safe from avoidable harm requires a much more sincere, thoughtful approach to what it means to learn at multiple levels of health care systems.

Patient safety has continued to be treated as an organisational problem – up to each hospital, care home or general practice to sort out for itself. But in reality, it is an institutional problem that affects the entire sector, requiring collective and coordinated action. Acting like a system – which the UK has an almost unique opportunity to do – could help to address the persistent challenge that when safety solutions are put in place, they are often poorly grounded in the available evidence, inadequately tested in local contexts, rely on magical thinking, and add to the stresses and strains on members of staff.

Local interventions, including those devised using quality improvement techniques, may ironically erode safety by undermining harmonisation of approach. The future will involve structures and models that can test generic solutions and enable local customisation, starting with problems that no single organisation can address on its own. Far more sharing of solutions will be facilitated. More attention will be paid to features of safety that have remained neglected, including individual practitioners’ technical competence, the extent to which teams function authentically as teams, the extent to which staff feel respected and valued, and clarity of goals throughout the system – from government downwards. Measures of past harm will be recognised as just one source of intelligence about safety; forms of soft intelligence and detection of hazards will be seen as just as (if not more) valuable.

The limits to quality improvement methods alone became apparent during the Safer Clinical Systems programme. The problems being encountered were too ‘big and hairy’ to be amenable to Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles – a key quality improvement approach – and were beyond the scope of small project teams. These deep, structural problems within providers require radical systems redesign, improved staffing, or new IT infrastructure; the solutions need to be owned by senior management and in some cases tackled industry-wide or across whole health economies.

Process standardisation can dramatically reduce variation between services and provide a platform for more sophisticated improvement techniques to flourish. It is an approach that has been more readily accepted in health care than some other sectors, in part through high-profile initiatives such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist. It can be most effective within health care environments where risks must be avoided at all costs. An example would be in the provision of cardiac catheterisation services (see Box 3).

Box 3: Standardising processes at the Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust

The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is a tool that brings together the whole operating team to perform a series of safety checks during critical stages of a procedure. A range of studies have reported reduced rates of complications and mortality following implementation of the checklist.

A team at the Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust adapted the checklist for use for the first time in a cardiac catheterisation laboratory (CCL), where certain heart conditions can be diagnosed and treated. The checklist is accompanied by a ‘team brief’ at the beginning of each patient list to outline any important points and anticipated problems. From eight months after roll-out and consistently since then:

- a full checklist is completed for 70% of procedures

- when the checklist is used, two-thirds of procedures have a shorter duration

- when the checklist is used, almost two-thirds of procedures have reduced screening times, meaning less exposure to radiation for patients

- survey data revealed that patients were reassured by the use of a checklist, and members of staff reported improved perceptions of safety culture, teamwork and collaboration.

The team is now developing checklists for emergency scenarios.

Box 4: Improving situation awareness in paediatric care across England

Studies show that implementing ‘huddles’ in health care can improve patient safety and reveal factors that contribute to potentially adverse patient outcomes. Led by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the huddle approach is being rolled out in 12 paediatric wards across England. It comprises three components:

- A nurse (or doctor) identifies patient risks using a standardised tool.

- Every four hours, the ward team evaluates patients with identified risks in a ‘huddle’.

- Three times a day, nurses from different wards meet with a safety officer to review any unresolved risks.

The approach is seeking to improve ‘situation awareness’. In this context, it means ensuring that all the necessary information is available to inform clinical decisions, using the perspectives of consultants, registrars, nurses, porters, patients and families. The project will conclude in 2016, and is aiming to reduce unsafe transfers of nearly 50% of acutely sick children on wards. Three NHS trusts in Yorkshire and Humber are seeking to scale up a similar approach to a whole-hospital level as part of the Health Foundation’s Scaling Up programme.

Other health care environments, however, rely on people’s skills and ingenuity, where risk has to be embraced as a necessary part of performing the service effectively. An example would be trauma surgery. This does not mean that processes cannot be carefully documented and standardised in such environments. It does mean that careful thought should be given to the context in which improvement methods are being considered. This involves recognition of the often unpredictable environment in which people work. Such environments often require more adaptive approaches to managing safety (see Box 4).

As with any other intervention to address quality or safety problems, to be successful, process standardisation has to be accompanied by other necessary ingredients: accurate safety measurement and monitoring, the engagement of people involved in the process, the setting of clear goals and – above all else – taking a sincere approach to its application.

Engagement and support

It is no longer acceptable to see patients, carers and families simply as the passive recipients of care; they are an asset that has been historically undervalued and underused in efforts to improve safety. Traditionally, their role has been consigned to one of providing feedback retrospectively about negative aspects of their care. Enhancing their role, however, can make different risks and harms more visible, particularly perhaps those associated with poor coordination, missed diagnosis, miscommunication or delays in care. This is because patients, carers and families can identify issues that may be missed by a member of staff, or even issues that staff have become accustomed to during the course of their day-to-day work.

There are a variety of ways in which patients, carers and families can contribute to safety improvement, including the following:

- By planning improvement, through the prospective collection of information to support service developments. This could involve patients acting as representatives on hospital design groups.

- By informing their care plan, where patients are encouraged to share all relevant information with the health professional, to ask questions about the treatment planned for them and to explore any alternatives.

- By monitoring the safe delivery of treatment, where initiatives are designed to help patients take an active role in their own safety. This could include seeking real-time information from patients about their experiences of unsafe care (see Box 5).

The success of efforts to involve patients in safety relies on the attitudes and behaviours of those providing care. This requires that those working in health care see the patient’s perspective as a valuable source of information; that the infrastructure is in place to deal with patient feedback; and that members of staff actively encourage patients to take part and ensure they feel able to do so. Equally, the ability of staff members to be able to do this depends on the degree to which senior managers and executives have engaged them in developing a shared goal for improving safety.

Box 5: Patient reporting of harm at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust

A team at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust developed and introduced a simple, real-time daily reporting tool to be used by patients and their families on an inpatient ward. One of the findings during the first observation period was that patients reported a higher proportion of ‘minor’ harms and ‘near-miss’ events, with the highest proportion of concerns relating to miscommunication, delays to care or problems associated with cleanliness.

During the same period, the team found that routine staff reporting of critical incidents increased by 67%. However, only 3% of the incidents reported by patients and families were also reported by staff. This illustrated how patients and families can play a critical ‘value-adding’ role in highlighting previously unrecognised risks.

This level of engagement by senior NHS leaders with those working for them must begin with a frank assessment of the existing level of safety within their organisation. However, evidence suggests this is not usual practice. In 2013, a study analysed the perceptions of boards in the UK and USA on the quality of care in their hospital. These perceptions were compared with some accepted measures of quality. The result was that ‘the boards of poorly performing hospitals had almost the same perceptions of those in the best performing – that quality was good’.

Avoiding complacency and being constantly concerned about safety are core components in creating a positive safety culture. Such a culture means that people feel comfortable discussing errors, and leaders and front-line staff take shared responsibility for delivering safer care. It can be the by-product of introducing a safety improvement intervention, but can also be undertaken as an intervention in its own right (see Box 6).

Box 6: Using human factors training to support a safety culture at Luton and Dunstable University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Between 2009 and 2011, a team at Luton and Dunstable University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust began a structured training programme to improve the teamwork and communication skills of people working in the maternity service. This was done through human factors training – understanding the range of factors that can affect people’s performance – and implementation of briefings, debriefings, closed loop communication, and structured ways to communicate critical information. As a result, the team reported statistically significant improvements in patient safety culture, teamwork, team morale and job satisfaction.

The project has since spread to the trust’s emergency department and the maternity service at neighbouring Peterborough Hospital. It has also been applied to a completely different setting as part of the Health Foundation’s project on Safer Care Pathways in Mental Health.

Viewpoint: What is the future of patient safety?

Creating the right culture, by Helene Donnelly OBE

Helene is Ambassador for Cultural Change at Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Partnership NHS Trust.

After the tragic cases of poor care at Stafford Hospital came to public attention in 2010, it was clear that the NHS needed a drastic culture shift.

Since then, positive steps have been taken, such as the introduction of the duty of candour and Freedom to Speak Up guardians.

Openness on the part of staff is crucial to protect patient safety and prevent needless harm; these are values that must be embedded across the entire health care system.

I have had direct experience of raising concerns in the NHS, when I spoke out about appalling standards of care and low staff morale at Stafford Hospital. I know how isolating, frustrating and frightening it can be. Raising concerns needs to be normalised so that it is no longer stressful and emotionally draining. People need to feel empowered and able to raise concerns before it affects patient care.

If we don’t look after the people working in the NHS, how can we expect them to look after patients? Low staff morale leads to increased stress, errors and sickness. This will clearly have a negative impact on the delivery of high quality, safe care.

Most professionals working in the health service already know that they need to be honest about mistakes they make, and constantly strive to do the best job possible. By truly listening to the people who deliver care when they have concerns, most harm could and should be prevented. However, as part of implementing the duty of candour, members of staff must be supported and encouraged by the organisations they work for.

But the duty of candour does not stop with front-line staff. Cultural change also needs to be owned by politicians and organisations. We are all responsible for ensuring that the necessary infrastructure and resources are in place for people to deliver high-quality care, free from intimidation.

A constant concern for safety means a willingness to root out the risks within a system. The Safer Clinical Systems programme supported teams to do just this, helping them develop safety cases for specific pathways. One team identified 99 separate risks (many of them previously invisible) associated with the handover of medical patients who needed surgery. Another team established that the care of one patient per week was compromised as a result of miscommunication of information between day and night teams. However, a working group on safety cases convened by the Health Foundation concluded that the large-scale adoption of such an approach ‘would require a maturity of approach that is not currently widespread, particularly in terms of avoiding blame and censure of those teams and organisations that do identify hazards in their systems’.

Viewpoint: What is the future of patient safety?

Re-thinking the role of regulation, by Harry Cayton CBE

Harry is Chief Executive of the Professional Standards Authority.

Might we help patients to be safer by regulating less? I think so. Health and social care regulation is overcomplicated, incoherent and costly, and there is little evidence of its impact on quality. More than 20 organisations have a role in regulating health and social care. System regulation across the UK costs upward of £450m a year, with a further £130m for professional regulation. These figures don’t include compliance costs.

At the same time, health and care are changing fast, the workforce is changing, medical technologies are changing, and public expectations are changing. If regulation was going to fix quality, it would surely have done so by now.

We need to rethink what regulation does well, what it can’t do, and what it should not do. We need to apply right-touch regulation principles consistently, to have a shared purpose for professional and system regulators, to use transparency to benchmark standards, to reduce the number of regulators and narrow their focus to the prevention of harms. Regulation should support and enable people to take responsibility and make safe decisions, not take responsibility and judgement away from them.

Regulation, by its legal and rule-based nature, sets standards and defines boundaries; regulation tends to stasis not change. But the health care of the future needs us to break down boundaries – to open up to new ways of working, to new relationships, to new structures. If we want to rethink quality in health care, we must rethink regulation too.

The ambition should be to move to a situation where open and honest conversations about risk and safety are commonplace across the NHS; where transparency is seen as a means of creating a positive safety culture rather than just being a requirement when something goes wrong. This could manifest itself across a wide range of relationships:

- For managers and front-line health professionals, it means moving from simply disclosing the details of a safety incident to routinely sharing with patients, carers and families all relevant information about their care, good and bad, in a way that makes them genuine partners in their care.

- For providers, it means moving from simply complying with national data requests and regulatory requirements to proactively making information available about the safety of their services using measures and methods appropriate to the local context.

- For the boards of providers, it means moving from ‘comfort-seeking’ behaviours to ‘problem-sensing’ behaviours; from simply seeking reassurance that all is well to proactively rooting out weakness within systems, however unpalatable the implications.

Strategy and accountability

As this report has shown, acheiving sustainable improvements in patient safety requires organisational factors including:

- a system for measuring and monitoring safety, including the impact of improvement interventions

- a systematic approach to improving safety using evidence-based and contextually appropriate methods

- the facilitation of open and honest discussions about safety and risks with staff members and patients.

This isn’t the only list of this kind, nor is it exhaustive. Organisations that have made significant progress on safety have done so on their own terms, building on the assets they already have in place. However, one common trait has been a shared, explicit approach to continuous safety improvement and the commitment to build skills and knowledge at scale and over time to support this. This means encouraging and enabling people to develop and deploy the skills, tools and knowledge necessary to improve the quality and safety of the care they provide. Organisations that have been successful in achieving this have done so by:

- getting early support from the board – for instance, by encouraging visits to similar organisations that have built improvement capability at scale

- giving careful consideration to resourcing – for instance, by offering coaching, mentorship and coordinating roles alongside people’s day-to-day responsibilities

- finding ways to free up staff time – for instance, by making training programmes as flexible as possible

- maintaining a consistency of approach and commitment over time.

Developing an organisational commitment to building capability is a prerequisite to delivering reliably safe care. However, in such financially challenged times, it is easy to understand why organisations may be reluctant to engage with this, particularly when empirical evidence on the cost-effectiveness of safety improvement interventions is in short supply. However, the business case for a systematic approach to building safety improvement skills and knowledge can still be made in the following ways:

- Unreliable systems are unproductive When people working in health care have to constantly develop workarounds in fragmented, unreliable systems to avert many more cases of harm, it acts as a drain on their energy, resources and goodwill. Our report, How safe are clinical systems? discovered that the clinical systems studied had an average failure rate of 13–19%. For instance, in nearly one in five operations, the equipment was faulty, missing or used incorrectly – or staff members did not know where it was or how to use it.

- Unsafe care is expensive In 2014/15, the NHS Litigation Authority paid out more than £1.1bn in litigation claims. This is expected to rise to £1.4bn in the coming years. However, these costs do not reflect the physical and emotional costs of harm – to patients, families and members of staff – or the time involved in investigating incidents that show a repetition of behaviours or causal factors.

- Safer care can reduce costs A number of projects funded by the Health Foundation have estimated cost savings that may be associated with their improvement work, alongside the primary objective of improving the quality of care for patients. One example is the work to improve care for frail, older patients in Sheffield (see Box 7).

Perhaps the strongest argument for this kind of systematic approach is that it helps to provide an underpinning strategy for everything the organisation does (see Box 8). And the rapid progress demonstrated by organisations such as East London NHS Foundation Trust – in 2015 named patient safety trust of the year and one of the best places to work in the NHS in England – shows that it can help to build a positive environment in which high-quality, safe care can thrive.

Box 7: Making the case for safety improvements at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

The Flow Cost Quality programme in Sheffield examined the flow of frail, older patients through the emergency care pathway with the aim of preventing queues and poor outcomes.

By testing and implementing changes to better match capacity with demand, the team succeeded in reducing the time taken to assess older patients by more than 50%. They also reported a 37% increase in the number of older patients discharged on the day of their admission or the following day – with no increase in the readmission rate.

In-hospital mortality for geriatric medicine reduced by approximately 15% and emergency care bed occupancy for older patients was reduced, allowing two wards to be closed. The team has estimated cost savings associated with the intervention of around £3.2m a year.

Box 8: Building improvement capability at scale at East London NHS Foundation Trust

An approach of continuous quality improvement has been embedded right across East London NHS Foundation Trust, and it is the principle that informs all of the organisation’s structures, goals and activities. A training programme allows staff to develop their quality improvement skills over a six-month period. Several hundred members of staff have already completed the programme and more than 100 current projects apply improvement methods, concepts and tools to complex quality issues.

One project was implemented within the three older adult mental health wards that had the highest frequency of physical violence. The trust has since reported that violence on these wards has reduced by 50%, with direct cost savings of £60,000 within six months; violence across all of the trust’s wards has reduced by 39% over a 29-month period.

Viewpoint: What is the future of patient safety?

Ensuring leaders have the right mindset, by Sir David Dalton

Sir David is Chief Executive of Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust.

The future of patient safety requires that we understand the processes, methods and behaviours which together create a safe system, environment and culture.

For leaders, this means:

- having clarity of purpose – expressing what they want to improve, how much by and by when

- being unequivocal about the values of their organisation, so that everyone knows the contribution they must make

- using measurement to determine whether change is achieving a system improvement

- having an organisational mindset that seeks high reliability, with leaders believing front-line staff are best placed to test whether changes to practice result in improvement capable of being replicated and spread across an entire organisation

- valuing the contribution of teamwork ahead of the charisma of heroic individuals

- being open and transparent, publishing data and results – celebrating success but learning from errors and what didn’t work

- recognising that a culture for patient safety comes from what leaders do and pay attention to, through their commitment, encouragement and modelling of appropriate behaviour.

Leaders should hear the patient voice and listen to staff; they should be visible and aware that they are, at all times, ‘signal generators’, reinforcing the authenticity (or otherwise) of those signals. The best leaders defer to the expertise of others and their instinct is to coach for improvement rather than direct it. These leaders already understand that the future of patient safety will no longer be found within their single organisation. They already know that they do not operate in isolation but are connected to the actions and behaviours of others in the systems they are connected to. They are already on the next stage of the journey.

Supporting safety improvement in practice

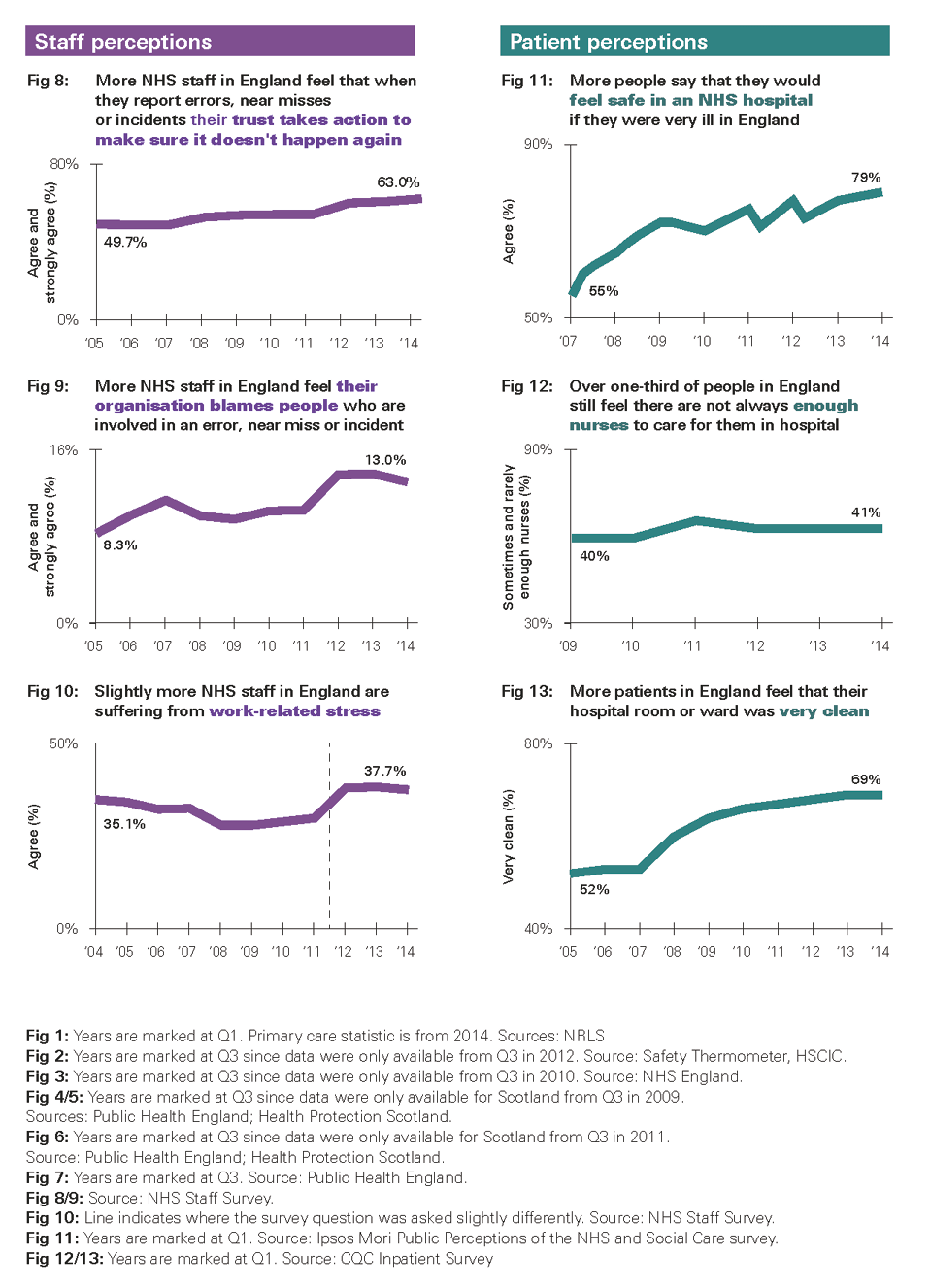

A checklist for safety improvement

Based on the evidence and experience presented in this report, we recommend the following checklist for safety improvement. The checklist is aimed at people working in provider organisations when tackling a safety problem. This might be to reduce the incidence of falls in a ward, or to improve the reporting of adverse events and near misses across an organisation. The checklist does not offer any easy solutions to improve safety; there are no easy solutions. Use of the checklist must be accompanied by the behaviours that can make change happen: sincerity, transparency and a commitment to continuous improvement. However, we hope it will be a useful reference point whenever a safety problem has been identified and when potential solutions are being considered.

Key steps for leaders of provider organisations

Improving safety at the front line does not happen in a bubble. It is influenced – whether enabled or hindered – by senior leaders within provider organisations. It is the responsibility of leaders to create an environment where improvement can flourish and to encourage the testing of ideas without the fear of failure. They also need to implement organisation-wide changes or national policies with a constant vigilance for any unintended consequences by actively seeking continuous feedback from patients, carers, families, employees and volunteers. The leaders of provider organisations set the tone for their culture through their stated values, their behaviour and their attempts (or lack thereof) to challenge or embrace deeply embedded taken-for-granted behaviours.

To translate these ideas into practice, we recommend three steps that leaders of provider organisations should take to build an organisation-wide approach to continuously improving safety:

- Work with staff and patients to develop an organisational strategy for improving patient safety. It could be based on an organisation-wide approach to building capability in improving quality and safety, but it must reflect and build on the experience and assets of staff members that are already in place.

- Build an organisation-wide approach for creating a positive safety culture. This could be based on an initiative to measure the different safety cultures that exist across parts of the organisation, but it must be done in a way that makes people feel safe to speak up and it must not be used, or seen, as a means of performance management.

- Develop an approach for how safety can be better measured and monitored across the organisation. This could be based on the framework developed by Charles Vincent and colleagues (see Figure 14), but it must be developed in partnership with those working on the front line and be accompanied by behaviours at board level that welcome, rather than supress, information about risks within services.

These three core steps cannot be taken overnight. They require deep thinking, challenges to established practices, and the involvement of everyone associated with the delivery of care. They are, however, critical, given that senior leaders act as the buffer between the front line and policymakers. The final part of this report explores how policymakers and system stewards can help to make safety improvement more effective.

§ See www.health.org.uk/safetysteps for a collection of useful resources to help take action on these steps.

Part III: Making the system safer

The policy and practice of improving patient safety are inextricably linked. Regulation, guidance, directives and other initiatives can have strong effects on the behaviour of organisations and individuals across the NHS. That is the point, of course. However, it is important to recognise how policy can ‘create the “latent conditions” that increase the risk of failure at the sharp end [as well as] generate organisational contexts that are conducive to providing high quality care’.

In our 2015 report, Constructive comfort: accelerating change in the NHS, we looked at the key factors needed for successful change and explored why they are not consistently present in the NHS. We identified three types of mechanism by which national bodies can effect successful change in the NHS: directing change from the outside; supporting organisations to make change; or seeking to influence the behaviour of individuals. The report concluded that previous efforts, which have largely focused on externally directing change, have had mixed success, and an approach which blends the three mechanisms coherently is likely to be most successful.

In the context of safety improvement, and building on the findings of the Berwick review, this means: ensuring appropriate accountability in rare cases of reckless or neglectful care; creating an environment that works with people’s intrinsic motivations to do good; and harnessing the collective effort to address the issues that make safety improvement so challenging. In this part, we set out how an effective system for safety improvement can be designed to enable these aspirations to become a reality. In doing so, it is important to understand how the current policy approach to patient safety is affecting the NHS.

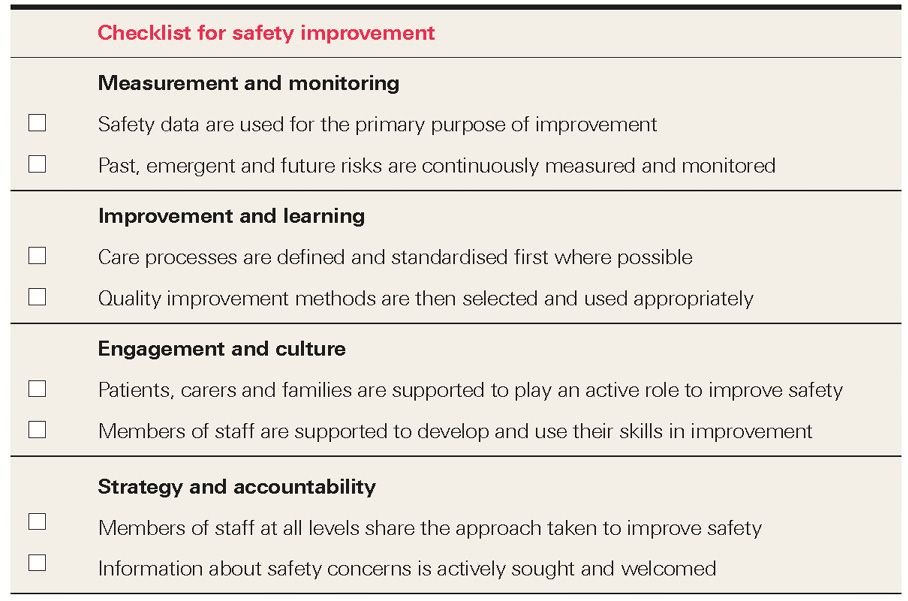

Perspectives from the NHS

In late 2014, we conducted interviews with 17 NHS board-level leads for patient safety across England. We wanted to understand how the policy and regulatory environment was perceived, and what effect it was having. While many of those we spoke to welcomed the increased national focus on quality and safety, a number of issues were raised. We heard concerns from acute trusts that financial pressures would take precedence over quality in the future, and concerns from mental health, ambulance and community trusts about an excessive focus on acute care. Regulation was generally felt to be moving in a positive direction, however, many of those interviewed were concerned about the resources being absorbed by multiple national reporting lines, and perceived a lack of strong leadership or a coherent push towards safety.

Organisations that had experienced recent problems highlighted particular concerns that close monitoring and scrutiny was hindering long-term planning and progress. Higher-performing organisations told us they want more standardised measurement so that performance can be benchmarked to enable learning from each other.

Many respondents also expressed regret that the ‘futility of blame’ message of the Berwick review was offset by the continued culture of defensiveness in the NHS. As illustrated in Figure 9, the number of people working in the NHS in England who felt their organisation blames or punishes the people involved in incidents rose from 10% to 13% between 2010 and 2014. Such trends illustrate the potential impact, direct or indirect, of national policy on members of NHS staff, and the extent to which this can hinder progress in the areas where a growing consensus is emerging about the future frontiers for patient safety.

Thinking differently about patient safety

It is difficult to argue against suggestions that health care can be made safer. But to begin to bring about change, all those involved in providing health care need to start thinking differently about how safety improvement is supported across the NHS. National bodies and policymakers can support this by encouraging action in the following three areas:

- Developing a culture and system of learning.

- Improving safety across multiple care settings.

- Managing safety proactively.

Developing a culture and system of learning

The fundamental principles and ultimate goal of improving patient safety is to create a system where there is continual learning from past events to mitigate future risks. While many of the most far-reaching national developments have focused on building systems and cultures of learning, many of them have fallen short. The National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) is one such example, where the original vision to identify problems rapidly in one part of the NHS and routinely develop and share solutions across the entire system has not been fully realised.

One reason this has happened is because people’s understanding of ‘learning’ is varied and vague. Learning is an active process that depends on collaboration and engagement between patients, professionals and policymakers to address practical problems. To have a material impact on patient safety, systems must be designed to provide people with the space and support to work constructively together on shared problems. Two emerging examples point the way.

- First, the government has committed to establishing an independent patient safety investigation function for the English NHS. The aim is to investigate rapidly, independently and routinely the most serious patient safety issues and make targeted recommendations for improvement across the entire health care system. Done effectively, this can ensure those working in health care actively examine and reflect on their practices, explore problems that span the health care system, and collectively develop and implement solutions.

- The second example is Q – an initiative, led by the Health Foundation and supported and co-funded by NHS England, connecting people skilled in improvement across the UK. Q will make it easier for people with expertise in improvement to share ideas, enhance their skills and make changes that bring tangible improvements in health and care. Q is bringing together a diverse range of people to form a community working to improve health and care. The aim of the initiative is to connect a critical mass of people in order to radically expand and accelerate improvements to the quality of care.

Improving safety across multiple care settings

Efforts to improve patient safety have historically focused on the hospital sector. This is because hospitals meet the needs of people with serious and immediate health concerns, where there is a greater risk of harm occurring. But the delivery of health care will increasingly shift out of hospital settings, and patient safety must follow. If care is going to be more integrated – where pathways of care will span multiple settings, where people will be increasingly managing their own conditions, or be cared for in their own homes rather than in controlled hospital environments – then those aiming to improve safety needs to respond.

A number of the Health Foundation’s improvement programmes have begun to test ideas to address the challenges presented by this shift. For instance, in East Kent, the acute trust has been working in partnership with the care home sector to implement a community geriatric team to tackle the problem of unplanned and avoidable readmissions. In Northumbria, structured medicines reviews are now done in partnership with care home residents to reduce unnecessary and potentially harmful medications. And in Airedale, a direct line has been established to link people in their own home or in residential homes with nurses and consultants outside of normal hours.

These types of approaches, which break down traditional organisational boundaries and see safety from the perspective of the patient, offer an exciting way forward for the recipients and providers of care alike. They also offer an insight into how safety can be managed more proactively, rather than simply waiting for something to go wrong before doing anything about it.

Managing safety proactively

Other ‘safety-critical industries’ have had their fair share of high-profile failures with tragic loss of life on a large scale – be it the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown in 1986 or the Tenerife airplane collision in 1977. As a consequence, these industries have embraced new ways of thinking more proactively about detecting hazards and managing risks in an effort to prevent any recurrence. For instance, tools such as risk registers are common in other industries, where they tend to be used in forward-looking ways to help diagnose problems in processes and identify prospective hazards. In health care, however, risk registers tend to be backward-looking, bureaucratic data-collection exercises. Though they often generate huge amounts of data, they are rarely used in a way that provides an accurate indicator of the next problem to arise or the underlying causes of harm.

What is the future of patient safety?

Developing a new architecture of safety strategies, by Professor Charles Vincent and Professor René Amalberti

Charles is a Health Foundation Professorial Fellow and Professor of Psychology, University of Oxford. Rene is Professor of Medicine, Haute Autorité de Santé.

Patient safety has been driven by studies of specific incidents in which patients have been harmed by health care. Eliminating these distressing, sometimes tragic events remains a priority but this ambition does not really capture the challenges before us. Patient safety has brought many benefits but we will have to conceptualise the enterprise differently if we are to advance further.

We need to see safety through the patient’s eyes, to consider how safety is managed in different contexts and to develop a wider strategic and practical vision in which patient safety is recast as the management of risk over time. Safety from this perspective involves mapping the risks and benefits of care across the patient’s journey through the entire health care system.

Safety is not, and should not be, approached in the same way in all clinical environments. The strategies for managing safety in highly standardised and controlled environments are necessarily different from those in which clinicians must constantly adapt and respond to changing circumstances. Health care will always be under pressure and we also need to find good ways of managing safety when conditions are difficult. We need to develop an architecture of safety strategies customised to different contexts, both to manage safety on a day-to-day basis and to improve safety over the long term. Such strategies are needed at all levels of the health care system, from the front line to the regulatory and governance structures.

Shifting away from delivering improvement through reducing incidences of harm to the proactive identification and management of hazards offers huge opportunities. It can help to diagnose more accurately known problems and surface previously unknown problems. While it is not possible to foresee and mitigate every possible risk, an organisation that is used to identifying, analysing, controlling and monitoring threats to patient safety routinely will be more resilient in the face of unexpected events. However, for such an approach to become commonplace across the NHS, there must be a system for safety improvement that encourages rather than inhibits this behaviour.

Our vision for an effective safety system

It is clear that work to improve practice at the front line and to develop organisation-wide approaches to safety will only yield limited further benefits if the issues identified in this report are not also recognised at the system level. We therefore set out a vision for an effective system for safety improvement, based on the four core themes used in the safety checklist presented in Part II: measurement and monitoring, improvement and learning, engagement and culture, and strategy and accountability.

We recommend that national bodies with a remit for patient safety, from across the UK, assess the extent to which their objectives, structures, policies and initiatives support the vision set out below. We ask them to reflect on any gaps or conflicts and take coordinated action to address them.

What does an effective system for safety improvement in the UK look like?

Measurement and monitoring

It is a system where it is made explicit that continuous improvement is the primary purpose of the use and publication of safety data; where safety measures strike the balance between past harm and future risk, and are sensitive to different settings and contexts; where a core set of national safety measures – including methods to collect the data – is agreed between the providers, commissioners, regulators and users of health care; and where safety data are regularly shared between oversight bodies, and the same information is not requested multiple times from providers of care.

Improvement and learning

It is a system where lessons from safety improvement work in one part of the system can be readily accessed and built on in another; where incidents and safety concerns are fully investigated at the appropriate level within the health care system; where the most serious safety concerns are routinely and rigorously investigated by an independent body; and where action to tackle systemic safety problems is coordinated at the regional or national level to include the providers, commissioners and regulators of care, and the manufacturers of health care products.

Engagement and culture

It is a system where people working in the NHS support and equip patients, their carers and families to take an active role in their own safety; where regional, national and professional training providers embed the science of safety and quality improvement in their programmes, to support the development of a critical mass of safety improvers; where providers continue to develop people’s skills and knowledge to tackle the most pressing safety problems; and where commissioners and regulators give providers the space, time and support to develop their own improvement capability programmes.

Strategy and accountability

It is a system where there is a long-term strategy for safety improvement agreed between all stakeholders; a strategy that sets out the need for a just culture and clearly marks the boundaries between culpable breaches of care and unintended failures; where there is a compact between providers and regulators, which fosters a mature dialogue when safety problems are detected, allows opportunities for providers to proactively demonstrate the safety of their systems, and makes explicit that providers are, first and foremost, accountable to patients and the public.

The progress made in improving patient safety over the past 15 years shows that the NHS has the will, skill and determination to make this vision a reality. Further improvements in safety will not be easy, and have to be achieved in the context of tightening financial constraints and increasing demands on the time and energy of people working in the NHS. But the many practical experiences and achievements of teams from across the NHS can act as inspiration to others. And important lessons from the past can help senior leaders and policymakers create an environment in which safety improvements can flourish in the future.

References

- Amalberti R, Vincent C, Auroy Y, de Saint Maurice G. Violations and migrations in health care: a framework for understanding and management. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(Suppl 1): i66-i71.

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the unexpected: resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007.

- National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England. A promise to learn – a commitment to act. Improving the safety of patients in England. 2013. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226703/Berwick_Report.pdf (accessed 13 October 2015).