Acknowledgements

The Health Foundation would like to thank:

The peer researchers in each site

All the young people who took part in the place based workshops

Julia Unwin CBE, Strategic advisor to the Young people’s future health inquiry

Jabeer Butt OBE, the Race Equality Foundation

Ed Cox, the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce

Dr Ann Hagell, Association for Young People’s Health

Leaders Unlocked, particularly Rose Dowling and Anna Crump.

Health Foundation colleagues, including Matt Jordan, Rob Williams, Rose Minshall and Miriam Brooks.

And all of the organisations who helped facilitate our visits, including Bradford City Council, North Ayrshire Community Planning Partnership, Bristol City Council, OTR Bristol, Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council, YMCA Lisburn, and Denbighshire County Council.

Foreword

The health of its young people is one of the biggest assets a country holds, determining its future wellbeing, costs and productivity. It forms the basis for the health of democracy, the economy and shapes the social fabric. For governments across the world, the stewardship of this asset needs to be a priority — any erosion is a major risk.

The gains made in young people’s health over the last few decades in the UK, specifically from the investment in early years, was the starting point for the Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry.

The inquiry’s first phase of research and engagement — described in our first report Listening to our future — found that while these gains are significant, other factors and experiences pose risks to young people’s safe and healthy transition to adulthood.

Many of these experiences are shaped by the places young people grow up: economy and opportunities, community and the availability of public services affect their life chances.

Over the past six months, we’ve visited five very different places and engaged with both young people and the people responsible for local systems and services to gain an understanding of growing up in the UK in the 2010s. Place may not be an absolute determinant of outcomes, but it still profoundly shapes experience, expectation and opportunity, and has implications for long-term health and wellbeing.

What we found tells a story of young people forging their own paths in creative and mutually supportive ways. But it also tells a much less comfortable story — young people profoundly affected by the nature of their local economy, housing and labour markets, and by the strength of the social fabric around them. It describes a sense of insecurity and lack of confidence, and shows that many of the protective factors that are so important for future health are missing. In many cases, this weakens resilience to inevitable shocks and setbacks, as well as jeopardising their long-term health.

The young people we met were proud of their home towns and strongly identified with them. Yet, they were all too aware that their life chances were determined by both the community and economy of these places.

That should be a major concern for us all. We should worry as if our future depends upon it. Because it does.

Julia Unwin — Strategic adviser to the Young people’s future health inquiry

Introduction

Between the ages of 12 and 24, young people go through life-defining experiences and changes. Most aim to move through education into employment, become independent and leave home, and it is also a time for forging key relationships and lifelong connections with friends, family and community.

These milestones have been largely the same across recent generations. But today’s young people face unique opportunities and challenges compared to their parents and carers, and from those they imagined themselves to be facing during their teenage years.

This matters because these building blocks — a place to call home, secure and rewarding work, and supportive relationships with friends, family and community — are the foundations of a healthy life. And there is strong evidence that health inequalities are largely determined by inequalities in these areas — the social determinants of health.So, while young people are preparing for adult life, they are also building the foundations for their future health. Young people’s future health isn’t simply their own concern, it is also one of society’s most valuable assets.

This report is the second from the Young people’s future health inquiry and outlines the findings from site visits to five places across the UK. In each location, the inquiry team listened to the perspectives of both a mix of young people who lived there and the people who work in organisations to support them.

The building blocks:

01 Marmot M, Goldbatt P, Allen J et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). The Marmot Review; 2010 (http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review)

About the inquiry

The Health Foundation’s Young people’s future health inquiry is a first-of-its-kind research and engagement project that aims to build an understanding of the influences affecting the future health of young people.

The two-year inquiry began in 2017 and aims to discover:

— whether young people currently have the building blocks for a healthy future

— what support and opportunities young people need to secure them

— the main issues that young people face as they become adults

— what this means for their future health and for society more generally.

The inquiry started with an engagement exercise, published in the Listening to our future report. The findings from the engagement work informed both a research programme run by the Association for Young People’s Health and the University College London Institute of Child Health and these site visits. The inquiry will conclude with policy analysis and development of recommendations in 2019.

Image 1:

The ‘assets’ needed for a healthy life

In the first phase of work, the Health Foundation identified the factors and influences that young people felt that helped or hindered their transition to adulthood. Over 80 young people, aged between 22 – 26, participated in five engagement workshops across the UK. From these workshops, four assets were identified as central to their current life experiences.

Right skills and qualifications: whether they had gained the academic or technical qualifications needed to pursue their preferred career.

Personal connections: whether they had confidence in themselves and access to social networks or mentors able to offer them appropriate advice and guidance on navigating the adult world.

Financial and practical support: direct financial support from their parents or carers, such as being able to live at home at no cost as well as practical assistance, including help with childcare.

Emotional support: having someone to talk to, be open and honest with and who supports their goals in life. This could include parents or carers, partners and friends, as well as mentors.

The initial engagement work showed that not all young people have these assets and whether or not they have them leads to particular patterns of experience, with some experiences reinforcing each other, and a number of broad groups emerging. For more information, see the Listening to our future report and the joint Health Foundation and Association for Young People’s Health working paper. A subsequent literature review supports the importance of these assets in providing young people with the best opportunity for a healthy life.

In addition to these four assets, the housing and labour markets were repeatedly identified as external factors that affect their chances of a healthy future.

02 Mentors here refers to any adult who is not a family member or partner. Mentors could be teachers, tutors, youth leaders, parents of friends or any other trusted adult.

03 Shah R, Viner R, Hargreaves D, Heys M, Varnes L, Hagell A. The social determinants of young people’s health. The Health Foundation and the Association for Young People’s Health; 2018 (https://www.health.org.uk/publication/social-determinants-young-peoples-health)

04 Hagell A, Shah R, Viner R, Hargreaves D, McGowan J and Heys M. Young people’s suggestions for the critical assets needed in the transition to adulthood: To what extent does existing research support their hypotheses? Health Foundation Working Paper. London: Health Foundation; 2018

The purpose of the site visits

Having established the factors critical to supporting young people’s transition into adulthood during the engagement work, the next stage of the inquiry was to understand how these factors were experienced by young people in their day-to-day life, in order to inform the areas of further policy analysis. We wanted to understand:

— are young people across the UK able to access the four assets?

— if so, what are the opportunities and conditions that enable to access them?

— if not, what is getting in the way?

The insights from this exercise will now inform the areas of further policy analysis.

We designed a programme to explore these questions in five places across the UK. Site visits took place between June and October 2018 in:

Methodology

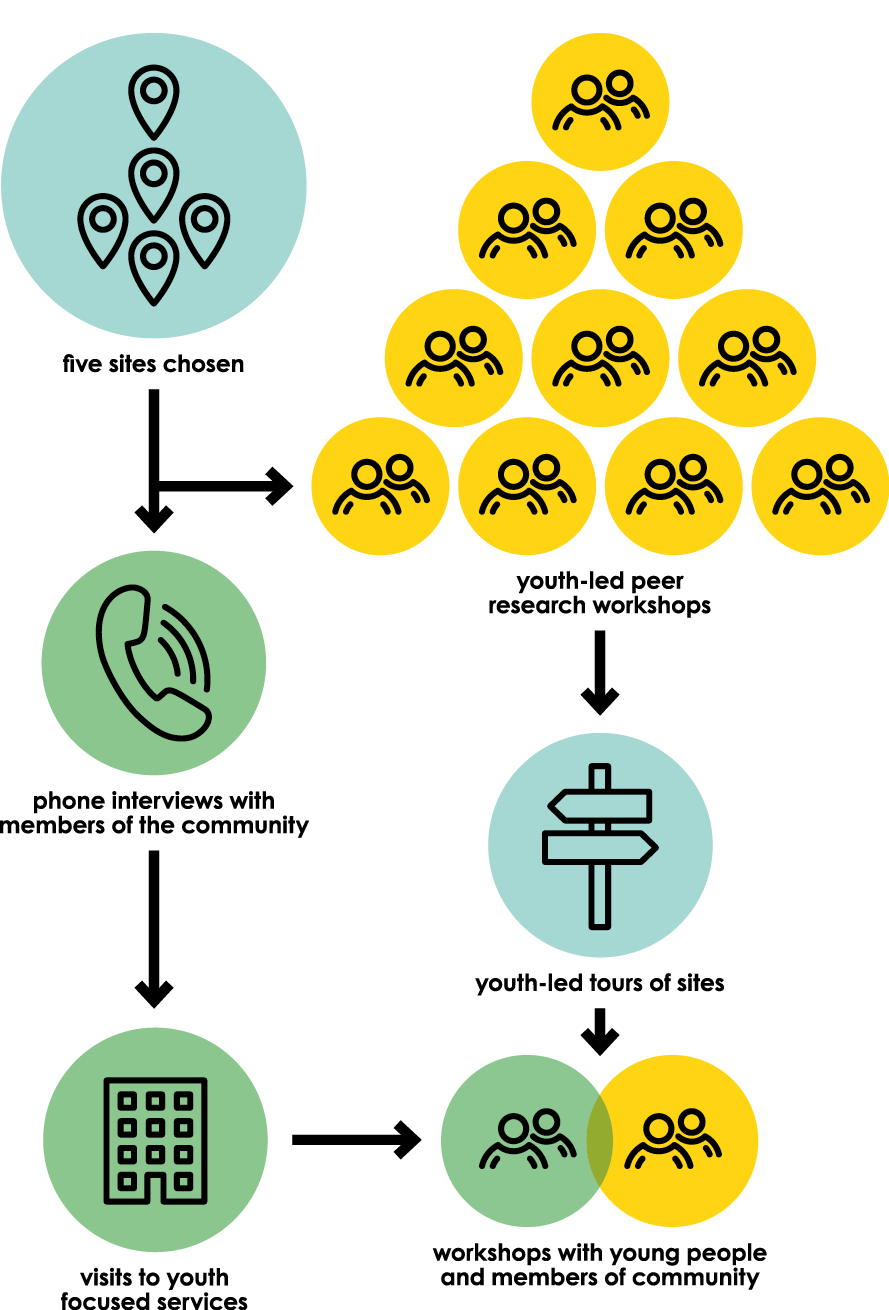

Five sites were chosen from rural, sparsely populated areas to inner city, ethnically-diverse areas. One site was chosen in each of northern England, southern England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. While the process was data driven, sites not intended to be fully representative of the UK; instead the aim was to generate qualitative information about how places shaped young people’s lives and their transition to adulthood from a sufficiently diverse range of perspectives.

Peer researchers: 10 –15 local young people aged 14 – 24 were recruited in each area, trained and supported to become peer researchers.

Ahead of each individual visit:

— 8 –10 youth-led peer research workshops too place in schools and youth services in each place involving around 120 young people aged 14 – 24. They aimed to gather their experiences of developing the four assets.

— 8 –15 telephone interviews with members of the community, usually local leaders or services, who shape the experience of young people in that place.

Each visit involved a youth-led tour, a visit to a youth-focused service and a four-hour facilitated meeting at which findings were presented and young people and members of the community met to debate and identify opportunities to improve young people’s experiences.

All materials were then reviewed for common themes for further consideration by the inquiry.

More details on the methodology can be found in the appendix.

Methodology diagram:

Emerging themes

Each place has specific local cultural, historical, economic influences shaping young people’s lives, as well as very different patterns of services. This means that the priorities for action, and how these could and would be addressed, varied. Nevertheless, across the five places, there were common themes, generally reflecting wider societal trends or national policies and how they play out in young people’s lives. These were:

Location and identity: the power of place.

Families and place: a changing support system.

Education and employment: developing the whole person and every person.

Youth services and opportunities: creating potential.

Transport: connecting places and people.

Location and identity:the power of place

Place matters to young people. Where someone is from shapes who they are in many ways: through the opportunities available, the culture of the place, the family and other networks around them and the level of belonging.

While some may argue that policy action over the last two decades and broader societal change has lessened the implications of place, our visits showed something different. Despite many UK-wide standards for service delivery, and approaches to resource allocation aiming to smooth out differences in outcomes — for instance in education and health — there is still wide variation in what is available. It has also been suggested that young people with high levels of digital engagement and access to global information and entertainment are perhaps less rooted in their birthplaces than once might have been the case, yet place clearly still has an impact on identity.

Each of the visits uncovered a strong sense of place, shaping the young people’s identity and how they described themselves. Access to the four assets varied in each location, both through the opportunities available to young people and in the relationships they could form.

Image 2:

Local perspectives

Pride, difference and belonging

Young people frequently referenced the neighbourhood they were from, either naming their housing estate, village or suburb and explaining the key features of that area. In Bradford, the young people strongly identified themselves with the geographic area covered by their postcode, using it as a shorthand to tell us about their ethnic background.

‘I’m BD9 me’ peer researcher, Bradford

Some of the young people could articulate stories from their community history, showing us historic sites and memorials, sometimes with associated pride and, on other occasions, with mixed or difficult feelings about what had taken place.

They voiced the way experiences in their own neighbourhood differed from those of the other young people that took part in the project. There was a clear sense of feeling safe within their own communities but not in other communities — even if they were home to other young people in the group. This reflected different community demographics and whether young people felt they ‘belonged’ or safe in a neighbourhood that was predominately from another demographic.

‘I was surprised doing the workshops. The young people from Clifton said that Easton wasn’t safe. I’m from Easton and I know that I am safe there, so it was strange hearing about how others don’t feel safe.’ peer researcher, Bradford

‘That estate… I wouldn’t go there’ peer researcher, Lisburn

Importance was also placed on spaces that helped different communities to come together and mix, which was commonly the city centre.

‘Things like the mirrorpool in the centre of Bradford has brought people together and creates a good will feeling — families come to paddle.’ organisation, Bradford

The young people told us that they valued meeting young people from different economic and ethnic backgrounds or from different locations through the research process. Many were aware of the community divisions but wanted to reach across these divides. Some were already able to do this via the groups and opportunities they took part in outside of school. Others felt that they were only able to mix with other young people like them and were keen to learn more about their peers.

‘I would never have met someone like her if I hadn’t done this’ peer researcher, Lisburn

Impact of economic opportunity and of service provision

The places we visited had very different opportunities available to young people, for example those with thriving economies were able to offer more diverse career prospects. This often affected how the young people spoke about the places they were from — those with the most opportunities spoke with the most pride, those with the least often used more negative terminology.

‘This is a great place to live with different ethnicities, and all types of people, shops and activities.’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘I want to get out of there. It is a lovely place to retire but it is hard to grow up there.’ peer researcher, Denbighshire

The impact of very different levels of service provision was visible. In some places, services once used by the young people had closed, or were no longer available at the times they needed them. This material difference in terms of education and health services, as well as youth services, was important in shaping their experience.

‘People applied for A-Levels at the college, then it was shut down’ workshop participant, Denbighshire

‘[A&E] isn’t open after eight o’clock. If you have trouble overnight you have to go to Belfast, or sort yourself out’ peer researcher, Lisburn

‘Do they care?’ — young people’s feelings towards local provision

The extent to which young people felt valued in the places they lived in was influenced by several factors. Often it was shaped by whether they felt that there were places or opportunities for them within their community, or whether these places and services were being maintained and prioritised.

‘The new skatepark isn’t as good. It is smaller, so it isn’t as safe. People injure themselves all the time.’ peer researcher, Denbighshire

A consistent concern voiced by the young people was the use of public spaces, like parks and streets, for drinking or drug taking — places they’d like to use recreationally but felt were too unsafe. They saw this loss of safe spaces as a reflection of the low value placed on them and their needs, and were keen that something should be done.

‘You can smell the weed and you can see the police right there, they aren’t doing anything’ workshop participant, Bristol

Across each location, there was a sense that the young people could adopt and embody the characteristics associated with their place. For example, in Bradford the young people were proud of their city, but they communicated a sense that it was looked down on by the wider area, and that this had an impact on their view of themselves.

‘They think Bradford is looked down on by Yorkshire… [and they] believed that if they put on their application form that they lived in Bradford then they wouldn’t get a place at [their] university of choice.’ organisation, Bradford

Where young people were actively involved in shaping their community they had a real sense of pride in the place. In North Ayrshire, there was an active youth engagement programme as part of the council’s approach to community planning and the young people involved expressed strong connections to their local place. Others involved in shaping a local youth activity project in Denbighshire talked about the sense of belonging that the project gave them and their ambitions to spread this.

‘This is the first one here, but we want every town in North Wales to be able to have a project like this one.’ peer researcher, Denbighshire

All the young people communicated passion for their places and a desire to make them better. A number told us this was their main reason for getting involved in the inquiry.

‘People say negative things about here but it is still our home, and we need to make it better.’ peer researcher, Lisburn

As a refuge or as a springboard

A large proportion of the young people who took part expressed a wish to build their future in their local area. This was apparent regardless of the employment and education opportunities available and appeared to stem largely from the family and community networks they had, security and a sense of safety, loyalty and belonging. It may also have reflected an unease with the thought of moving away.

‘One word to sum up Bristol? Home’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘I think I’ll have to end up leaving here to get a real job eventually’ peer researcher, North Ayrshire

Young people recognised the difference the local housing context could make to their ability to build a future in their home town. Many talked about whether they were likely to be able to afford housing in the future and how this shaped their sense of whether they would be able to stay. Some who were keen to stay in the areas they grew up felt that this would be unachievable as housing had become so unaffordable.

‘We have the most affordable houses in the country here. That is the statistic.’ peer researcher, North Ayrshire

‘The prices there now… I can’t afford to live where I grew up’ peer researcher, Bradford

The local leaders the inquiry interviewed often described their responsibility to equip young people with the skills and qualifications they need to make the choice between whether to stay or leave and also soft skills, such as confidence. However, the consequences of young people leaving and not coming back was not lost on them.

‘[This is a] place where you can start anywhere and go everywhere…if we collectively enable young people to enter adulthood brim-full of confidence, optimism and skills to navigate adult life, I could die happy.’ organisation, Bradford

‘If they stay and thrive that is a success. If we equip them to be able to go somewhere else and thrive that is a success.’ organisation, North Ayrshire

‘Young people go to university from here and don’t come back. This impacts the greater feel good.’ organisation, Lisburn

The sense of belonging felt for their wider community was important and often associated with a local organisation or institution. Faith-based organisations, community organisations and other opportunities that brought people together were often expressly described as providing emotional, financial and practical support for young people.

‘Church is a huge emotional safety net for me because I have hundreds of people I can go to for emotional support, and it’s local. I don’t have to travel far to find the help’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘Communities with similar income support each other and chip in if someone needs something.’ workshop participant, Bradford

Image 3:

The national picture

The importance of placed-based approaches to meeting people’s needs and supporting their wellbeing is being increasingly recognised in policymaking. This reflects an increasing understanding of how important place is to wellbeing. For young people specifically, research has found that feeling safe walking in their area after dark, liking their neighbourhood and feeling a sense of belonging are specifically associated with higher wellbeing.

While Office for National Statistics (ONS) data show that around two-thirds of people feel that they strongly belong to their local neighbourhood, the importance of place — and what makes it important — varies as we age. Data suggests that younger people feel broadly less connected to their place than older people do: approximately half of young people aged 16 – 24 still say that they feel they belong strongly or fairly strongly to their neighbourhood, compared to around three-quarters of people older than 65. But this doesn’t mean young people lack loyalty or commitment to the places they live: other ONS data shows that 60% of 18 to 24-year-olds feel that people where they live are willing to help their neighbours, not dissimilar to the 70% reported across the age bands.

Place is additionally important for young people as it is not only the place that they currently live, but it will also become the place that they are from, their ‘childhood home’, with the associated emotional connections this brings. A poll in 2016 found that nearly half of all people in the UK currently live near to their childhood home, with quality of life and proximity to family and friends cited by participants as key reasons for this.

Polling conducted for this report suggested that 43% of 17 to 18 year olds plan to leave their home towns, with 30% suggesting lack of job opportunities in their chosen field are motivating this move. However, 82% say they will miss being near to their family, friends and support networks.

The movement of young people away from the communities where they grew up may also be a factor in other studies that have profiled young renters in work as some of the loneliest in society, in part because this group lack a strong sense of belonging to their neighbourhood.

In addition to the influence of the labour market, the impact of changes in universal service provision across the UK, is also having a less visible effect on young people. 15 to 24-year-olds in England, and Northern Ireland use libraries more than other age groups, but the hours that libraries are open have reduced in recent years. Young people are more likely to use parks more often than older age groups but budgets are declining and facilities are ageing. Young people who participate in sport are more likely to have high levels of happiness, and less likely to have lower levels of happiness, than those who did not, a factor that can easily be ignored in a time of cuts to sports and leisure facilities.

It has also been suggested that the social fabric in many localities is in decline, as regular church attendance and membership of voluntary organisations decreases. While there is still some civic engagement across the population, just over one-third of people provide nearly 80% of participation in civic associations and 90% of volunteering hours. This third are most likely to live in the least deprived parts of the country. In turn, there is concern that inequality could be exacerbated, with more prosperous communities better placed to organise themselves to respond to community matters.

Image 4:

Why this is important to the assets required for a healthy future

The site visits showed that young people’s opportunities to access the four assets were heavily shaped by the place they lived. While emotional support largely starts with family, the opportunities offered to young people from voluntary or statutory organisations have a critical role in filling gaps and providing alternative sources of emotional support when needed. Furthermore, the prevailing culture in communities and neighbourhoods can shape how emotional support is sought, offered and accepted.

Opportunities to gain skills and qualifications are a direct consequence of the schools and colleges available. However, many valuable soft skills are acquired by engaging in community-based activities or connecting with local businesses. The personal connections young people can make are inherently rooted in the community they grow up in and the organisations that are there to support them. Finally, the practical, sometimes financial, support that strong communities offer young people as they grow up can make the difference between opportunities remaining aspirational or being instrumental in fulfilling young people’s potential.

Image 5:

05 Jennings W, Lent A, Stoker G. Place-based policymaking after Brexit: In search of the missing link?. University of Southampton and NLGN; 2018 (http://www.nlgn.org.uk/public/wp-content/uploads/policymaking-after-Brexit.pdf)

06 LankellyChase. Historical review of place based approaches. LankellyChase; 2017 ( https://lankellychase.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Historical-review-of-place-based-approaches.pdf)

07 British Academy. Where we live now. British Academy; 2017 (https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/WWLN%20Making%20the%20case%20for%20place-based%20policy_web.pdf)

08 Office for National Statistics. Measuring National Well-being: Exploring the Well-being of Young People in the UK. Office for National Statistics; 2014

09 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Community Life Survey: 2017-18. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport; 2018 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/734726/Community_Life_Survey_2017-18_statistical_bulletin.pdf)

10 Office for National Statistics. 5 measures of social capital by regional and urban and rural by age [webage]. Office for National Statistics; 2016 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/datasets/5measuresofsocialcapitalbyregion andurbanandruralbyage)

11 TSB. Home. Homebirds; 2016 (https://www.tsb.co.uk/tsb-home-reports-homebirds.pdf)

12 The Office for National Statistics; Loneliness – what characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? [webpage]. The Office for National Statistics; 2018 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/lonelinesswhatcharacteristicsandcircumstancesare associatedwithfeelinglonely/2018-04-10)

13 Peachey J. Shining a light. Carnegie Trust UK; 2017 (https://www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/shining-a-light/)

14 Thorpe V. Library houses across England slashed by austerity. The Guardian; 7 October 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/oct/07/cuts-to-library-hours-across-england-under-austerity

15 Heritage Lottery Fund. The State of UK Public Parks. Research Report HLF’; 2016

16 Unison. Counting the cost: how cuts are shrinking women’s lives. Cuts to local services. Unison; 2014 (https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2014/06/On-line-Catalogue224222.pdf)

17 Lakey J, Smith N, Oskala A, McManus S. Culture, sport and wellbeing: findings from the Understanding Society youth survey. NatCen; 2017 (https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Culture%20sport%20and%20wellbeing%20-%20youth.pdf)

18 Patel R. The state of social capital in Britain. Understanding Society; 2016 (https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/legacySocial_Capital_Policy_Final_formatted_-_USE.pdf?1464099031)

19 Mohan J, Bulloch SL. Working Paper 73: the idea of a ‘civic core’: what are the overlaps between charitable giving, volunteering, and civic participation in England and Wales?. Third Sector Research Centre; 2012 (https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tsrc/research/quantitative-analysis/wp-73-idea-civic-core.aspx)

Families and place: a changing support system

The family into which they are born and raised has a major role in shaping young people’s life experience, preparing them for adulthood and building resilience and capability. The role of extended families of grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles, as well as friends, neighbours and the wider community, can be just as important as their immediate family. The site visits illuminated a range of different circumstances, patterns of family life and varying strengths of social fabric around families.

While the methodology used in the site visits meant that the final presentations focused on the role local leaders could play, many young people in the workshops emphasised their families as sources of emotional, financial and practical support, as well as sources of personal connections. They reflected on a range of family relationships: often it was about the reliance on family as a core source of emotional support, but some also wanted to protect their already hard-pressed parents from their own challenges. Others who had fractured relationships with immediate families members found their extended families, and adults working in youth services, to be critical sources of support.

Several young people had family responsibilities, mainly as parents themselves but some with caring responsibilities for siblings or their parents.

Image 6:

Local perspectives

The role of family and wider society

The importance of the role of family in supporting young people to prepare themselves for adult life, such as in developing the skills to live independently, was widely felt. However, there was concern from young people and particularly from local organisations, that not all could rely on their families and social networks to deliver this.

‘Like cooking, I learnt cooking from my mum, but not everyone’s mum is gonna teach them how to cook’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘My parents encourage me to save money every week to my bank account, and use my Saturday job to save up. Once you’ve seen people struggle you don’t want the same [for your children]’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

Young people’s aspirations also emerged largely from their family environments. We heard uplifting stories of young people inspired to take different routes because of encouragement from their family members. Conversely, some organisations told us of young people coming from a family culture that did not value work. Some families were very proactive in seizing opportunities on offer, particularly when they were designed to reach less advantaged groups.

‘My mum is really proud of me. She wants me to get out there and show what Pakistani women are capable of.’ peer researcher, Bristol

‘We do work with some families where no one has had a job, so they don’t support their children in looking for a job’ organisation, Lisburn

However, young people told the inquiry their options were expanded or limited by the wealth, knowledge, skills and connections of their families. Organisations and young people both recognise that those from wealthier backgrounds have greater access to volunteering and work experience opportunities. They also identified how divisions between communities with different ethnic or cultural backgrounds limited who a young person could approach for advice or connections.

‘If you’re from a poorer background you don’t necessarily have the luxury of having spare time to be able to go to groups and extra things’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘I could ask anyone in my community. If I wanted to run a restaurant there would be so many people who would be able to help me. I want to be a lawyer though.’ peer researcher, Bradford

While the importance of familial and social connections in providing emotional support was evident, there was less of a clear role for formal services.

‘Mum, youth club and parents are all emotional support’ workshop participant, Bradford

However, there was recognition that not all young people have trusted sources of emotional support, particularly some young men. Some participants at our workshops described having no one among their friends and family they could lean on. The consequences of wider societal expectations that ‘boys don’t cry’ and that they should ‘man up’ were seen to be particularly damaging, especially to working-class and black, and Asian young men.

The context of poverty and deprivation

‘I took the test and I got into the grammar school, but when we went to buy the uniform I changed my mind. I couldn’t make my parents pay for that’ workshop participant, Lisburn

‘There are entrenched inequalities [for some families] with 2 or 3 generations unemployed’ organisation, Denbighshire

Young people described the impact of poverty and deprivation on their family. They could clearly see how a precarious labour market combined with very low family income made it difficult for their parents to fulfil their role in supporting them into adulthood.

This was not confined to places with higher levels of deprivation. Even in more affluent places, young people from poorer families or neighbourhoods within these areas said this impacted on their family life and their mental health. Some young people described a hesitancy in discussing personal issues with their family, as they didn’t want to add further pressure.

‘I feel like I can’t talk to my mum because she’s working all the time, she’s stressed enough anyway. I don’t wanna add to her stress with my problems’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘My mum is a single mum, two kids, but the financial stress is a lot for her, which means I don’t talk to her about my problems’ workshop participant, Bristol

Across all the places we visited, organisations described parents who were under such pressure that their ability to emotionally support their children was stretched to the limit. The young people talked about needing to support parents in a changing world.

‘Parents aren’t trained to be parents. How do they cope…? Who do they talk to?’ peer researcher, Lisburn

The attitude of statutory services differed across the places visited. Some did not see it as their role to engage extensively with the families of young people, and would accept some families as ‘difficult to engage’. In other areas, the interventions and support offered by organisations and services took a more family-based approach to ensure that the young people were supported. North Ayrshire took a ‘trauma-informed approach’, meaning adverse childhood experiences inform all their interactions with some families.

Changing family shape

The impact of divorce and re-marriage on family life and the transition into adulthood was raised with examples of young people who had felt encouraged to leave the family home, or who felt unwelcome as the family structure changed. For some, this seemed to have accelerated their move to adulthood. We also heard cases of family tension, including step-parents and step-siblings eroding the security the young people felt at home.

At the same time, there were descriptions of parents supporting their children well in very challenging circumstances. Young people were often living at home after they had finished school, either while they worked or went to university. Parents supported with childcare for their grandchildren and some step-parents were also described as positive role models.

The role played by extended families was varied. Some young people lived a long way from other relatives, while some grew up supported by a network of people, with grandparents in the same estate or same road.

‘I like my area because I can play football with my cousin because if you have no friends at least you can call your cousin or brothers’ workshop participant, Bradford

While extended families might not always offer great support — and there were several stories where it was either stifling or intolerant of difference — feedback was generally that they are a strong positive influence.

‘I have great people around which helps me to achieve my dreams’ peer researcher, North Ayrshire

‘I am strongly supported by my friends and family, I don’t know what I’d do without them’ workshop participant, Bristol

Image 7:

The national picture

The last half-century has seen broad changes to family structures, with many more teenagers growing up in varied household structures, including ones where both parents work. The impact of family life during teenage years is under-researched and there is limited understanding of which factors ensure a good transition to adulthood. However, data shows that young people regularly arguing with parents and not having a family member who they can rely on was associated with lower wellbeing.

Family environment, including economic background, shapes the development of ‘soft’ skills such as confidence and leadership, which are often acquired through participation in extra-curricular activities, such as music or sports lessons. While this is an effective route for some, relying on these services maintains socio-economic inequalities as they are often paid for. 66% of pupils from a high-affluence background take part in extra-curricular activities, compared to 46% from low-affluence.

The role of family support is also changing. The ONS found that young adults (aged 20 to 34) in the UK are more likely to be sharing a home with their parents than any time since the beginning of collecting comparable data. In 2016, there were 618,000 more young adults living with their parents in 2015 than in 1996 — 3.3 million compared with 2.7 million. With age limit restrictions on housing benefit and minimum wage, plus increasing costs of private housing in many parts of the UK, families are increasingly providing this type of financial and practical support. This means relationships have to be renegotiated as the children move into adulthood and can introduce new and different pressures on family life.

Image 8:

Why this is important to the assets required for a healthy future

A positive family life provides a child with opportunities for a healthy life by creating the early foundations for them to feel loved and valued; build supportive relationships; develop intellectual, social and emotional skills; and develop lifelong healthy habits.

Families support young people in developing the right skills and qualifications, whether through creating aspiration and a sense of possibilities, or in a less formal way as the source of skills, particularly ‘softer’ ones, which are in demand in some workplaces.

In many cases, families continue to be the main source of financial and practical support — not just while children are dependent but also whenthey are young adults, often providing somewhere to live and subsidising of day-to-day expenses.

20 (Forthcoming in 2018) Williams T. What could a public health approach to family justice look like?. Nuffield Family Justice Observation

21 ONS (2014) Measuring National Well-being - Exploring the Well-being of Young People in the UK, 2014 Newport: ONS

22 Cullinane C, Montacute R. Life Lessons: Improving essential life skills for young people. The Sutton Trust; 2017.

23 Office for National Statistics. Why are more young people living with their parents [webpage]. Office for National Statistics; 2016 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/articles/whyaremoreyoungpeoplelivingwiththeirparents/2016-02-22)

24 Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC medicine. 2014; 12:72

25 Allen M, Donkin A. The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. UCL Institute of Health Equity; 2015 (http://cdn.basw.co.uk/upload/basw_13257-1.pdf)

26 Dyson A, Hertzman C, Roberts Tunstill J, Vaghri Z. Childhood development, education and health inequalities. Report of task group. Submission to the Marmot Review. 2009 (http://www.instituteofhealth equity.org/resources-reports/early-years-and-education-task-group-report/early-years-and-education-task-group-full-report.pdf)

Education and employment: Developing the whole person and every person

Schools and colleges were the common denominator in the lives of the young people who participated and were seen as having the potential to provide much more than academic qualifications. At their best, they could connect young people with wide recreational, employment, support and developmental opportunities in their communities. But in practice, many felt educational institutions were not knitted into their communities and therefore, opportunities to play this integrative role in young people’s lives were lost.

This was reflected in the range of education experiences young people described even across schools in the same area. This was not just in terms of the academic offer but also in culture and attitude. The importance of school in developing young people’s emotional wellbeing and as a bridge to work and voluntary opportunities were common themes.

Image 9:

Local perspectives

Supporting the whole person

‘At school you’re told exams are everything, but they’re not everything. We still have feelings but feelings don’t seem to matter anymore. The stress is too much’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘There is an obsession with the idea of attainment, that is just about getting GCSEs, which is not a particularly helpful way to get a rounded understanding of what they need... it doesn’t make young people fit with the needs of the labour market either.’ organisation, Bradford

Young people and local leaders across all the sites talked about the impact of academic pressure on mental health. Young people reported an overriding emphasis on exams and qualifications at their schools. They felt pressured, which in turn often led to them putting huge demands on themselves and limiting wider interests so they could concentrate on their studies.

‘Schools are focused on what is on paper and in the records’ peer researcher, Lisburn

The results-driven culture was seen to limit teachers’ ability to support students outside of the core curriculum. The teachers who took part in our site visits told us they wanted to be able to teach wider than the exam curriculum, or have the time and emotional capacity to be able to deliver pastoral care, but opportunities to do so were squeezed.

Where schools offered emotional support through nurses or counsellors, young people in several places were concerned about the lack of confidentiality — those receiving counselling told us it was often visible to classmates and left them feeling exposed. Some described this as making the situation worse.

‘The school nurse will come into the classroom and call out your name so everyone knows where you are going’ peer researcher, Bristol

‘There’s a glass window into the office and so you can always see who is in there’ peer researcher, Lisburn

Too narrow a focus

The lack of adequate information and advice about non-academic routes into the workplace was consistently raised by young people and local leaders. Many schools encouraged university entry at the expense of everything else and were unable to offer advice or connections helpful to young people wanting to pursue other routes.

“I am not sure what I want to do, but I am pretty sure that I don’t need a degree to do it.” workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘career prospects should be treated equally…in grammar schools medicine and law are treated as the only options, which is bad if you don’t want to do those jobs’ peer researcher, Lisburn

The decision to pursue different forms of education after the age of 16 was also influenced by the funding available — something that varied across country boundaries. In Scotland, where young people pay less, there was more movement between options, with some moving from apprenticeships to higher education and vice versa.

‘after leaving school I went on to do an apprenticeship which allowed me to go on to university and now I am back working in North Ayrshire. So much of my learning took place in North Ayrshire and I feel a big part of this was the support offered by organisations and the local authority.’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘I can get connections though work not through school’ peer researcher, Bradford

Both local leaders and young people voiced concerns about the absence of opportunities to develop the wider skills and attributes essential for them to have a successful future — confidence, resilience and problem-solving skills. They did not feel schools were solely responsible and indeed, many were developing these skills outside of school. But this resulted in an uneven distribution with young people in more disadvantaged communities losing out.

Creating broader opportunities

‘It is ridiculous that at 18 you could be moving out, managing all your own bills, and 3 months before you are still putting your hand up in class to go to the toilet’ peer researcher, Lisburn

Young people wanted greater opportunities to understand the wider world including the world of work. However, with pressures on school budgets and teachers who were not best placed to be delivering life and employability skills, these were limited.

‘It seems pathetic to get a teacher to do a half-hearted attempt on a topic they’re not experts in when… they’ve got enough on their plate’ workshop participant, Bristol

In some places, closer partnerships between schools and local community organisations and businesses meant that life skills could be taught by outsiders. Examples included personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) lessons on financial management by local bank staff or a credit union. In Bristol, lessons on emotional wellbeing were delivered by an expert voluntary sector organisation. Young people valued these partnerships and said they would like them to be ongoing rather than occasional.

Local universities have an important role to play in supporting greater participation in tertiary education. For example, young people in Bristol described the tailored support that Bristol University’s Bristol Scholars programme had given them in making their application as well as financial support if they took up a place.

Employment and volunteering

The extent to which employment opportunities depended on the nature of the local economy was noticeable. In some places, weekend or holiday jobs were available for those in education and where they were not, financial inequalities were exacerbated. Those not continuing in education after the age of 18 often faced precarious or low-paid employment opportunities or needed to have the means to travel to neighbouring towns and cities to access work. Personal connections could sometimes help but many struggled to even understand what kinds of jobs they could apply for — job descriptions were felt to be puzzling and the demand for relevant experience was often a barrier.

‘On my zero hour contract its so unstable that one week I can earn £200 and the next week, £20’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘I work at the [local hotel]. I heard about the job through my aunt who works there’ peer researcher, Bradford

‘Some young people can find employment with some of the big employers such as the council and on the industrial estate. However, the area never really recovered from the closure of the very large mental health hospital… Many young people born in Denbighshire travel to Cheshire and Liverpool for work.’ organisation, Denbighshire

‘[For employment it’s] not a great area — quite rural —so not a lot of job opportunities — so young people have to travel’ organisation, North Ayrshire

In some places, organisations such as Nacro in Denbighshire and South Bristol Youth provided employability and skills training — and some tailored interventions — that were delivering results. These often relied on the strength of the relationships between these organisations, schools and businesses. In North Ayrshire, a collaboration between the council, leisure centre, job centre and the college supported unemployed young people to train for roles in the leisure sector.

Opportunities for volunteering were often instrumental in helping young people build the soft skills and connections needed to access the job market. However, many young people in more challenging economic circumstances were not able to volunteer, again compounding inequality in opportunity.

‘I honestly think if I hadn’t volunteered, I wouldn’t have got into university. It made that much of a difference.’ peer researcher, Bristol

Image 10:

The national picture

The education sector has a significant bearing on young people’s lives and their futures. The total funding allocated to the education sector varies across the UK nations, but there is a broad picture of fewer education resources being available to this age group, especially when increasing pupil numbers are considered.

Many in the education system are worried about the academic pressure put on young people. Young Minds reported that 90% of school leaders have seen an increase in the number of students experiencing anxiety or stress over the last five years. 82% of teachers say the focus on exams has become disproportionate to the focus on the overall wellbeing of their students and that 80% of young people believe exam pressure has impacted on their mental health. This pressure is also reported to be having an impact on teachers too. To address this in England, Ofsted have recently announced a change to their inspection protocol.

There is an increasing interest in young people’s transition into work and how much value is put on vocational training. The Sutton Trust reports that just one in five secondary school teachers would recommend vocational routes to their highest achieving students and only 32% of parents believe that an apprenticeship would be the best route for their child. The bias towards university-based education does not reflect earning potential: on average, those who achieve a level 5 higher apprenticeship have higher lifetime earnings than those with a non-Russell Group university degree. There are signs that this failure to value vocational training is contributing to skill shortages across the UK. For example, the Construction and Infrastructure Market Survey 2018 reported that 60% of businesses see labour shortages are a serious constraint to growth.

In addition to vocational training, there is rising recognition of the importance of soft employability skills, including leadership, teamwork and self-management. The Confederation of British Industry found that most employers were dissatisfied with the employability skills of school leavers. Additionally, only 22% of teachers felt that their students were prepared for the workplace once they left school. School students themselves recognise these gaps: research by the Sutton Trust revealed that 88% of young people reported life skills as more important than their academic achievement and 73% understood them as important to finding employment.

Government action in modernising education is both varied across the four UK countries and is achieving mixed results. In England, the reformation of the PSHE curriculum is under consultation. The National Citizen Service (NCS) was introduced in 2011 with the aim of providing young people with broader life skills but there are doubts about its effectiveness — despite its large budget it only reached 93,000 young people in 2016 – 17. An overhaul of the Welsh curriculum is currently underway and incorporates preparation for the workplace. However, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has warned that some schools are ill-prepared to implement the reforms due to unequal funding practices.

Scottish education policy has had an explicit emphasis on employability since the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) was implemented in 2010. Scotland has the lowest rates of 16 to 18-year-old NEETs (not in education, employment or training) of the four nations. There have been some concerns over the lack of academic rigour associated with CfE, given the recent slips in literacy, numeracy and science rankings according to the Programme for International Student Assessment. Northern Ireland has had Education for Employability embedded in its curriculum since 2007 but it is uncertain whether it has been successful, given broader economic context and the high levels of NEET among 16 to 24-year-olds in the country (19% in 2013).

Outside of formal education, there has been a marked increase in young people participating in volunteering. In 2010 – 11, 23% of 16 to 24-year-olds said they volunteered formally (that is, through a group or organisation of some kind) at least once a month. By 2014 – 15 that figure was 35%, a 52% increase, amounting to around one million more young volunteers.

While this has been ascribed to recent campaigns to engage young people in volunteering, such as Step Up to Serve’s #iwill campaign, there has also been suggestions that today’s young people favour a bottom-up approach to change and are motivated to make a difference in their communities.

Image 11:

Why this is important to the assets required for a healthy future

The site visits illustrated the pivotal role that education and employment play in providing young people with the assets needed for a smooth transition into adulthood.

At their best, schools and colleges do far more than equip young people with skills and qualifications. Extra-curricular programmes can provide personal connections that are useful in building confidence and understanding wider learning and employment opportunities. The school curriculum, and how it is delivered, directly influences young people’s emotional wellbeing. Where schools and colleges provide effective pastoral care, they are an important alternative source of emotional support but when services are absent or provided insensitively, they risk actively eroding young people’s self-esteem and wellbeing.

Good quality employment opportunities are an important source of financial support while in education or training, and can be invaluable for young people from less advantaged households. Work experience — paid or voluntary — develops a wider set of skills, including the personal connections needed to progress in the workplace.

Image 12:

27 Sibieta L. School funding per pupil falls faster in England than in Wales. Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2018 (https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13143). Roberts N, Bolton P. School funding in England. Current system and proposals for ‘fairer school funding’. Briefing Paper. House of Commons Library; 2017 (https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06702#fullreport). Belfield C, Farquharson C and Sibieta L. 2018 annual report on education spending in England. The Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2018 (https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/R150.pdf)

28 Young Minds and NCB. Wise Up: Prioritising wellbeing in schools. Young Minds; 2017 (https://youngminds.org.uk/media/1428/wise-up-prioritising-wellbeing-in-schools.pdf)

29 National Education Union. A survey report by the National Education Union on teacher workload in schools and academies. National Education Union; 2018(https://neu.org.uk/latest/neu-survey-shows-workload-causing-80-teachers-consider-leaving-profession)

30 Busby E. Ofsted to drop focus on exam results in school inspections, chief inspector says. The Independent; 12 October 2018.

31 Kirby P. Levels of Success: The potential of UK apprenticeships. The Sutton Trust; 2015

32 The Edge Foundation. Skills Shortages in the UK Economy. Edge Bulletin 1; 2018

33 Debate Mate. Social Impact Report 2016–2017; 2017

34 Messer D. Work placements at 14-15 years and employability skills. Education Training, Vol. 60 Issue: 1, pp.16-26; 2018 DOI 10.1108/ET-11-2016-0163

35 Griggs J, Scandone B. How employable is the UK? Meeting the future skills challenge. LifeSkills created with Barclays; 2018

36 Cullinane C, Montacute R. Life Lessons: Improving essential life skills for young people. The Sutton Trust; October 2017.

37 Kay L. Government likely to evaluate National Citizen Service next year. Third Sector; 20 August 2018 (https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/government-likely-evaluate-national-citizen-service-next-year/policy-and-politics/article/1490781)

38 Walker P. Cameron’s £1.5bn ‘big society’ youth scheme reaching few teenagers. The Guardian; 2 August 2018 (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/aug/02/david-cameron-15bn-big-society-national-citizen-service-reaches-few-teenagers

39 Comptroller, Auditor General. National Citizen Service Report 2016 – 2017. Cabinet Office and Department for Culture, Media & Sport; 2017.

40 Welsh Government. New Curriculum Update: May 2018. Policy and Strategy; 2018.

41 Lewis B. School Funding: ‘Inequality could hamper’ new curriculum roll-out. BBC News; 25 October 2018

42 Powell A. NEET: Young People Not in Education, Employment or Training. House of Commons Library. Briefing Paper; 2018.

43 BBC News. New Curriculum Could be ‘Disastrous’, says education expert. Scotland Politics BBC News; 3 September 2017 (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-41134835)

44 Northern Ireland Curriculum. The WOW factor: An Introduction to Education for Employability. Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessments; 2008 (http://www.rewardinglearning.org.uk/microsites_other/employability/documents/wow_factor/year_11/intro.pdf)

45 Crees J, Dobbs J, James D, Jochum V, Kane D, Lloyd G, Ockenden N. UK Civil Society Almanac [webpage]. NCVO Civil Society Almanac 2016 (https://data.ncvo.org.uk/almanac16/)

46 Duffy B, Shrimpton H, Clemence M, Thomas F, White-Smith H, Abboud T. IPSOS thinks. Beyond Binary: The lives and choices of Generation Z. IPSOS Mori; 2018 (https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2018-07/ipsos-thinks-beyond-binary-lives-loves-generation-z.pdf)

47 Demos. Introducing Generation Citizen [webpage]. Demos; 2014 (https://www.demos.co.uk/project/introducing-generation-citizen/)

Youth services and opportunities: Creating potential

Each place we visited provided opportunities for young people outside the formal educational structure, whether in the form of clubs, events or services. These aimed to enrich, build skills and resilience or just offer ‘something to do’ and the young people who took part were generally positive and appreciated the sense of purpose and a shared identity they created.

The exact nature of the services and opportunities varied within and across the sites with a mix of council and voluntary or community sector provision. Funding mechanisms were also varied. Some followed national programmes or models, such as NCS or the Army Cadet Force, while others were locally-based, adaptive and innovative, including Off The Record in Bristol and Denbigh’s Youth Shedz initiative.

Funding cuts were frequently raised as a concern by system leaders and this may partly explain why these services are not always visible to young people. However, even when provision was known about, many young people found them difficult to access without public or private transport.

Image 13:

Local perspectives

Value of services

The contribution of youth services was universally valued. For some, they provided structure and purpose while others said they provided meaningful activity and the opportunity to develop skills, which could be a gateway to employment or further education. Young people welcomed the more tailored support that youth services offer, often in contrast to their experience of formal education.

‘I attended youth groups in the local area that were a massive support and provided new opportunities and a space for me to grow.’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

‘The youth group has helped me connect with people who have similar interests and because of the music studio we can develop our skills and come together to create something’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘Before I went there [to a group] I was basically just bumming around’ peer researcher, Bradford

‘Personal connections is a big thing in youth work…one of the most valuable things we do is connecting people to other people and organisations they wouldn’t normally meet’ organisation, Bradford

‘School don’t support with careers, they are too professional so when we go to youth club the support is more personal’ workshop participant, Bradford

Youth services were also mentioned as a safe place for young people to gather. They offered emotional support from both peers and adults, with who they could form less formal bonds than with teachers or medical professionals. Levels of trust between young people and the adults appeared to be higher than for educational or health services.

‘They honestly care about you’ workshop participant, Bristol

‘I feel really supported and they care, like a bigger family. They all come from different walks of life so it helps with anything I want to know.’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

Funding youth services

In all the places we visited, securing funding was difficult although the challenges varied, not least as the funding mechanisms differ across the UK.

Most places referred to the inadequacy of funding to meet the current level of demand and the reliance on unpredictable grant funding, making it hard to plan services over the long term. Grant funding also tended to be aimed at service innovations, which further limited funding available to support core offers. Voluntary sector organisations spoke of the time spent filling in bids and losing good staff when short contracts ended.

‘Our biggest barrier is our capacity, which is largely determined by our funding. Funding is quite tight, we are always applying for it.’ organisation, Denbighshire

‘We’re filling in bids all the time. It takes up a lot of time’ organisation, Lisburn

Coping with the funding shortfall was a common preoccupation. We heard of service closure, particularly where services had previously been delivered in more than one location. We also heard of increased ‘gatekeeping’, where limitations were put on which young people could be involved. In some places, there were high-quality facilities but a lack of revenue stream meant they were not fully used. All these funding challenges were also visible to the young people using the services.

‘We can’t run universal services anymore’ organisation, Bristol

‘Service existence becomes more important than outcomes’ organisation, Bradford

‘There was one youth club in my area and I loved going when I was younger but it has closed down now and there is nothing in the area. It’s sad because that’s where I feel like I grew up.’ workshop participant, Bradford

Communication of youth services

‘Opportunities are only opportunities if young people find them and the opportunities find the young people’ organisation, Bradford

A common observation was that there was ineffective communication about the youth services available. Young people frequently talked about there being little to do, while organisations would describe low uptake for the activities provided. In one place where the young people had said there was little to do, a youth worker had organised a summer trip for young people but 35 places were left unused. Several peer researchers said that they had had little idea of what was available in their community before they talked to people as part of this work.

However, there were examples of communication working well. In North Ayrshire, services had a strong social media presence, including Instagram and Snapchat, and Bristol had several websites with youth-generated content providing information on opportunities.

It was felt that young people could play a crucial role in communicating about services, particularly the benefits. They said they were more likely to listen to peers who were already involved in activities than formal information.

‘If I’m going to spend my time doing something I want to know what is in it for me.’ peer researcher, Bristol

Youth consultation and participation

Some places demonstrated the power of working with young people through consultation and participation, but the extent to which these approaches were embedded varied. Bristol had a long-established youth council and youth mayor, both actively involved in local authority consultations. Lisburn had recently set up their youth council, the first of its kind in Northern Ireland. North Ayrshire involved young people in community planning partnerships, with elements such as participatory budgeting and community partnership actively reaching out to young people.

‘Some Community Planning Partnerships are tick box exercises… in North Ayrshire there is genuine commitment to working collaboratively for young people and adults’ organisation, North Ayrshire

‘[We ran a consultation with young people] about what they want from [personal, social, health education and citizenship] PSCHE lessons. We’ve had over 900 responses’ organisation, Denbighshire

Youth services seemed to be better tailored to the wants and needs of young people in the places with higher levels of youth consultation, participation and co-production.

Image 14:

The national picture

Youth services can improve the lives of young people. A qualitative evaluation of services in England found that young people’s participation enhanced wellbeing, friendships and confidence. YouthLink Scotland found that youth work delivers £7 return for every £1 invested and suggest that this is due to its positive impact on confidence, friendships and soft skills.

The picture of reduced funding for youth services across the places we visited also reflects the national trend. While the levels vary, in all UK nations there have been reports of reductions in funding for front-line youth services.

Youth participation in the design and co-production of services has been shown to be effective in delivering better outcomes.

Supporting successful co-production demands different skills and behaviours to those needed for the planning and delivery of services. The clearest example of these approaches embedding into core business is in Scotland, where policymaking is informed by evidence that suggests involving children and young people develops better policy that more clearly reflects their views and understanding, as well as developing skills knowledge, understanding, confidence and self-esteem among participants.

Image 15:

Why this is important to the assets required for a healthy future

The value of effective youth provision goes much wider than the immediate benefit to the individual. Taking part in community life, such as youth clubs, can be empowering for young people and create a sense of purpose, while also protecting health and wellbeing.

Youth provision can connect young people to the world around them, and when done well, provide a chance to build valuable personal connections beyond the family and school. The positive friendships fostered in these environments protect young people from the damaging health effects of social isolation.

The activities provided by youth services can also help young people develop the soft skills that can open doors to better, more high-paid and skilled work.

Over and above this, groups and organisations can provide important emotional support to young people. The first phase of the inquiry identified how important it was for young people to have someone to lean on emotionally, and there is evidence that good relationships with an adult can reduce the likelihood of mental ill health in later life.

Image 16:

48 Cooper S. The Impact of Youth Work in UK (England): ‘Friendship’, ‘Confidence’ and ‘Increased Wellbeing.’ The Impact of Youth Work in Europe ed. Ord J et al; 2018.

49 YouthLink. Social and economic value of youth work in Scotland: initial assessment. Youth Link Scotland; 2016 (https://www.youthlinkscotland.org/media/1254/full-report-social-and-economic-value-of-youth-work-in-scotland.pdf)

50 UNISON. A future at risk: Cuts in youth services. The Damage, UNISON; 2016

51 UNISON Scotland. Growing Pains: A survey of youth workers. UNISON Scotland - Youth work; 2016

52 StatsWales. Income for youth services. Welsh Government; 2018. (https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Education-and-Skills/Youth-Service/Finance/incomesummary-by-localauthority)

53 NICVA. 2016-17 Department for the Communities Budget. NICVA; 2017 (http://www.nicva.org/article/2016-17-department-for-the-communities-budget)

54 Social Care Institute for Excellence. Co-production with young people. Social Care Institute for Excellence; 2016 (https://www.scie.org.uk/co-production/people/young)

55 Aked J, Stephens L. Backing the Future: Practical guide 1. Action for Children and nef https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/d745aadaa37fde8bff_ypm6b5t1z.pdf)

56 Collaborate/New Local Government Network (NLGN). Get Well Soon: Reimagining Place-Based Health – The Place-Based Health Commission Report. London: NLGN; 2016. (www.nlgn.org.uk/public/wp-content/uploads/Get-Well-Soon_FINAL.pdf)

57 Daly S, Allen J. Inequalities in mental health, cognitive impairment and dementia amongst older people. UCL Institute of Health Equity; 2016 (http://cdn.basw.co.uk/upload/basw_53658-8.pdf)

58 Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS. Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-School and Community Programs. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2005

59 Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(3):488.

60 Hughes K, Davies AR. Homolova L, Bellisi MA. Sources of resilience and their moderating relationships with harms from adverse childhood experiences: Report 1: Mental illness. Public Health Wales; 2018 (http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/888/ACE%20&%20Resilience%20Report%20(Eng_final2).pdf)

61 Chatterjee K,Goodwin P, Clark B, Jain J, Melia S, Ricci M. Young People’s Travel – What’s Changed and Why? Review and Analysis. The Centre for Transport & Society, UWE Bristol & Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford; 2018 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/448039/young-car-drivers-2013-data.pdf )

Transport: Connecting places and people

Transport issues were cited during all our site visits as a barrier to education, employment and other activities by both the young people and organisations.

Transport provided a connecting role in young people’s lives and when absent, limited their ability to take advantage of opportunities. This increases the inequalities in access to the services and activities that will help them build the assets needed for a smooth transition into adulthood.

The specific nature of the difficulties varied across the places visited. Sometimes it was simply a case of availability, in others it was cost or frequency. Whatever the reason, the importance of transport and the challenges young people faced accessing it, was perhaps the most unexpected finding across the five sites. National policy analysis shows that these difficulties are echoed across other parts of the UK.

Image 17:

Local perspectives

Lack of public transport infrastructure

The young people and organisations talked about the lack of transport infrastructure. Issues such as getting to education and work in time for lectures and shifts were raised and in some cases, young people talked about making specific educational choices based on the transport available.

‘I’ve stayed on at sixth form at school as it just wasn’t possible to get to college on time.’ peer researcher, Denbighshire

In rural areas, cuts to bus services were discussed. In Denbighshire, some young people said there were only four buses a day between their village and the local town. In North Ayrshire, there was only one remaining bus route young people could use to get to the towns along the coast and they felt inland journeys had become more difficult. This lack of availability of transport affected the uptake of work — if a young person did not drive, they were usually reliant on parents to take them, as taxis were too expensive. This tended to deepen inequalities as not all parents could afford a car, or if they did own one, were unable to drive their children where they needed to go, particularly if they were working long hours or shifts.

‘Young people are often held back by a lack of transport’ organisation, Denbighshire

Young people and organisations in the cities also talked about poor transport infrastructure. A ‘hub and spoke’ model where routes to the centre are strong, but routes between suburbs are weaker, means journeys could take more than two hours and several changes of bus. There was concern among organisations that this deepened inequality, with opportunities available to those in the city centre that were not available to others who lived further out. In Bristol, service delivery organisations were concerned that vital services, including mental health services, were increasingly being delivered in the city centre, so not all young people needing them could access them.

‘Transport isn’t very accessible, unless you live really close the centre, the bus links are too spread out and not frequent enough’ workshop participant, Bristol

There was also a concern that poor transport infrastructure, when combined with service closures or ‘rationalisation’ was particularly damaging. Efforts to deliver more streamlined community services, are undermined if young people do not have the transport to access them.

Cost of public transport

The young people also talked about the high cost of transport being a barrier, particularly to work. Some young people made calculations of how much they would have left after paying for transportation, particularly for shorter shift work.

‘If I was to get the bus to work it would take half my wages away’ workshop participant, North Ayrshire

Transport costs were also seen as barriers to other activities — young people living in cities explicitly talked about how ‘free’ activities in the city centre were not open to them as they could not afford the fares.

‘When you go to secondary school, managing friendships is harder because you live in different areas and services, transport and activities are expensive, therefore limited’ workshop participant, Bristol

There was a compounding effect of a lack of affordable transport. Often those who were most likely to benefit from activities were least able to afford the cost of transport involved in accessing them. However, some youth participation programmes paid transport costs, making it more likely that young people from poorer backgrounds could get involved.

Private transport — cars and driving

Many young people were dependent on driving, or from lifts from other drivers. Few could drive or owned a car of their own. If they did have a car, they cited enormous difficulties in affording it and sacrifices they had to make to do this, including around their education. Usually, it was more affluent young people who could afford to learn to drive and access a car.

‘I now have a contracted job… so I can pay to have my car insured and on the road, but before that, I was working a number of zero-hour contracts at mad times and through the night. I did that because I knew eventually it would pay off and I’d be able to afford to get a car on the road, and then be able to take myself to work. Before that, I was calling my mum up at all hours of the night — it wasn’t fair… I couldn’t do all of that and commit to full time education, so I had to choose.’ workshop participant, Bristol

In Bradford, there was a specific issue voiced about bad driving and uninsured drivers. This had a knock-on impact on insurance premiums for the young people and many could not afford to drive as a result.

‘There is an issue with bad drivers in Bradford, and it affects driving for everyone else’ organisation, Bradford

Image 18:

The national picture