Key points

In April 2017, the House of Lords Select Committee on the long-term sustainability of the NHS concluded that the biggest internal threat to the sustainability of the NHS is the lack of a comprehensive national strategy to secure the workforce the NHS and care system needs.

This report examines the current position with regard to two of the most important issues in workforce policy:

- nurse numbers and staffing standards

- pay policy.

These pose both immediate and long-term risks to the ability of the NHS to sustain high quality care.

Nurse numbers and staffing standards

There are currently not enough nurses in the NHS in England. This shortfall is likely to be exacerbated by poor workforce planning.

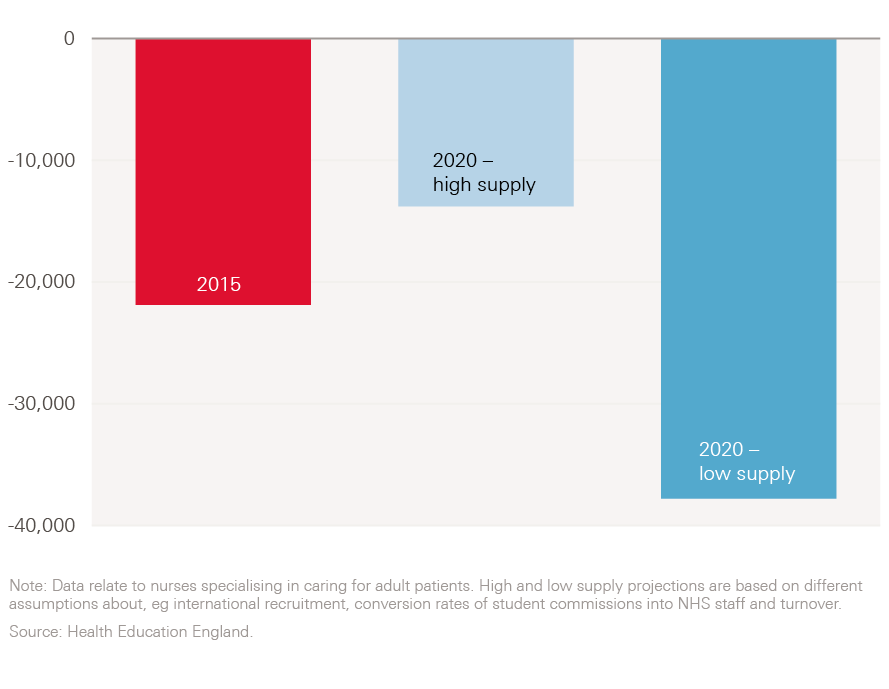

- In England, there was a shortfall of 22,000 nurses specialising in caring for adult patients in 2015 (almost 10% of the workforce).

- Even under the most optimistic scenario for the supply of nurses, the NHS is expected to have a shortage of 14,000 nurses specialising in the care of adult patients in 2020. Under the more pessimistic national scenario, the shortfall will be 38,000 nurses – equivalent to 15% of the workforce. For all nurses (not just those specialising in adult patients), under the most optimistic scenario for supply a 5,000 shortfall is expected, and under the more pessimistic scenario the shortfall will be 42,000.

- This crisis becomes more acute following the decision to leave the EU. One in three new nurse registrations in 2013/14 were by people from EU countries other than the UK. In the NHS in England, 7% of nurses and health visitors are from other EU countries – and the number has increased by 85% since 2013 to 22,000, while the number from elsewhere (including the UK) has increased by just 3%. Worryingly, the number of applications for nursing degrees from people from other EU countries is 25% lower this year than last year – the biggest decrease in any domicile group. In addition, 3,500 nurses with EU nationality left the NHS in 2016 – twice as many as in 2014.

- Half (49%) of nurses don’t think there are sufficient staffing levels to allow them to do their job properly. This percentage has remained broadly flat since 2010, despite the drive to recruit more nurses following the Francis Inquiry.

- Between 2010 and 2015 we’ve seen a substantial shift in the mix of staff groups employed by the English NHS. The number of full-time equivalent consultants has increased by more than a fifth over just six years, while the number of nurses has risen by just over 1%.

- This rapid change in skill mix of the NHS workforce has been associated with falling productivity in NHS acute hospitals. A recent Health Foundation report, A year of plenty?, reinforces the need for integrated, whole system workforce planning. It finds that hospitals with a higher proportion of nurses have higher consultant productivity. Increasing the proportion of nurses in a hospital by 4% was associated with 1% more activity per consultant.

- Given the pressure on numbers, ensuring that nurses are deployed well to support safe and efficient delivery of care is vital. There has not been a sustained direction for national policy on safe staffing and there has been limited progress in England on any national advice or guidance on how to determine safe staffing.

- Allowing local organisations autonomy to make decisions about staff numbers may become the lead policy in England. However, this will have to be shored up by necessary checks and balances to minimise the risk of a major quality failure linked to inadequate staffing. To ensure that this approach is effective, the NHS needs to focus on two critical enablers:

- It needs more effective local management capacity and responsiveness in analysing, determining, implementing and monitoring ‘what is safe’.

- It will also need to make much more rapid progress in identifying, and networking ‘what works’ in terms of local team-based safe staffing tools and approaches, and effective use of local data and systems.

Pay policy

Between 2010/11 and 2020/21 the pay of NHS staff will have declined in real terms (ie adjusted for inflation) by at least 12%.

- On the back of commitments to workforce pay in the 2000 NHS plan, pay in the NHS rose in real terms between 2000 and 2010, outpacing the rest of the economy.

- Since then the picture has been quite different: between 2010 and 2017 the real value of health and social care staff’s pay has fallen by 6% (while in the economy as a whole it has fallen by only 2%).

- In March 2017, the NHS Pay Review Body (NHSPRB), working within the government’s pay policy, recommended that all the Agenda for Change pay scales for NHS staff across the UK are increased by 1% from April 2017. This covers most non-medical staff employed by the NHS.

- Taking into account inflation forecasts and the pay policy for the rest of the decade, the NHSPRB calculated that NHS pay at Agenda for Change band 5 and above will have been cut by 12% in real terms over the decade from 2010/11 to 2020/21.

- At national level there is a need to prepare the pay determination system for the ‘end of the freeze’ on national pay. Pay constraint is currently planned by the government to be in place until at least 2020. However, the time is right to assess the options on how best to determine the total reward package for NHS staff, and decide if the current system continues to be fit for purpose, if it requires some alteration, or if it is time for substantial change. The NHS needs a pay policy that will enable it to recruit, retain and engage the workforce it needs to succeed.

Workforce planning

Workforce planning is essential to ensuring productivity and demonstrates the need for a clear and coordinated workforce strategy.

- The Five year forward view (FYFV) set out an ambitious programme to transform the NHS in England. Realising that ambition in a period of unprecedented financial constraint is always going to be challenging, but without the engagement of the million-plus people who work in the NHS it will be impossible. The NHS still has no overarching strategy for its workforce.

- Piecemeal policymaking, however well-intentioned any individual initiative might be, is not serving the NHS well. The NHS will not be able to move forward to deliver sustained efficiency improvements and transform services without a serious examination of its approach to pay and the way it plans and uses its nursing workforce across the system.

- Pay restraint and reductions in headcount for groups such as infrastructure staff have been important planks for achieving financial balance over recent years. However, they do not represent a long-term strategy to achieve sustainability or deliver change.

- Proper workforce planning is required that looks across different staff groupings to evaluate impact – not focusing purely on the numbers of consultants or nurses separately. It is clear that the lack of a coherent workforce strategy, which is integrated with funding plans and service delivery models, is one of the Achilles heels of the NHS.

Workforce priorities

The NHS is facing unprecedented challenges: it is seeking to transform services to meet the fundamental changes in population needs as society ages and chronic mental and physical health problems become ever more prevalent. Transforming a service as important and complex as health care would be a challenge at any time, but to do so during a decade in which funding is growing more slowly than at any point in the history of the NHS makes that essential transformation process even more difficult.

Health care is a people business – the NHS employs over 1.3 million people; social care even more. Combined, they employ around 10% of the UK workforce. The health care workforce is highly skilled – doctors, nurses and allied health professionals account for over half of those working in the NHS and require education and training to graduate level and beyond. It is also an expensive workforce and over two-thirds of hospital budgets are spent on pay. NHS and social care average earnings per person are 16% higher than average earnings across the economy as a whole.

How well the NHS is able to recruit, retain and mobilise the workforce to deliver the best care as cost-effectively as possible is fundamental to a successful and sustainable health system. The task of transforming services, which the NHS in England set itself with the Five year forward view (FYFV), is now being taken forward through 44 local sustainability and transformation plans (STPs). This transformation will only be achieved through the active engagement of the workforce. It will require a different mix of skills and staff as services move from an acute, curative focus to more prevention and proactive management of complex patients with multiple long-term conditions in community settings.

The current policy of NHS funding constraint places major limits on the scope for policy manoeuvre on NHS staffing, both locally and nationally. The Health Foundation’s 2016 report on the profile and features of the NHS workforce in England, Staffing matters; funding counts, emphasised that there is an essential and continual policy interconnect between funding and staffing, but that too often funding and workforce policy are disconnected. The report argued that the NHS lacks an overarching workforce strategy that can support the FYFV.

Staffing matters; funding counts used the labour market frame to illustrate the interconnected nature of policy and the need to be clear about the effects – anticipated and unintended – of any policy intervention. It also highlighted that the NHS has an uneven track record in taking account of the full impact and implications of new health workforce policies.

We will follow up Staffing matters; funding counts later in 2017 with an updated look at the workforce of the English NHS. Before then, however, it is clear that the lack of a coherent workforce strategy, integrated with funding plans and service delivery models, is an Achilles heel of the NHS.

The FYFV set the NHS in England the task of delivering annual efficiency improvements of 2–3% a year. NHS Improvement’s analysis shows that acute hospital efficiency improved by an average of 1% a year in real terms between 2008/09 and 2014/15. Over the next few years the NHS will have to substantially accelerate the drive for efficiency improvement if it is to sustain the quality of care and access to services.

Health care is a people-intensive sector and improving labour productivity is essential to drive improvements in overall efficiency on a sustainable basis. Over recent years, the NHS has often looked to one-off initiatives to improve efficiency. A prime example is the abolition of strategic health authorities (SHAs) and primary care trusts (PCTs), which reduced the cost of commissioning and system oversight. This approach was appropriate when the government thought that austerity would be relatively short-lived, but the NHS is facing at least a decade with funding growth of around 1% a year above inflation, compared with rising pressures of around 4%. This gap can only be bridged through sustained improvements in the underlying productivity of the health service.

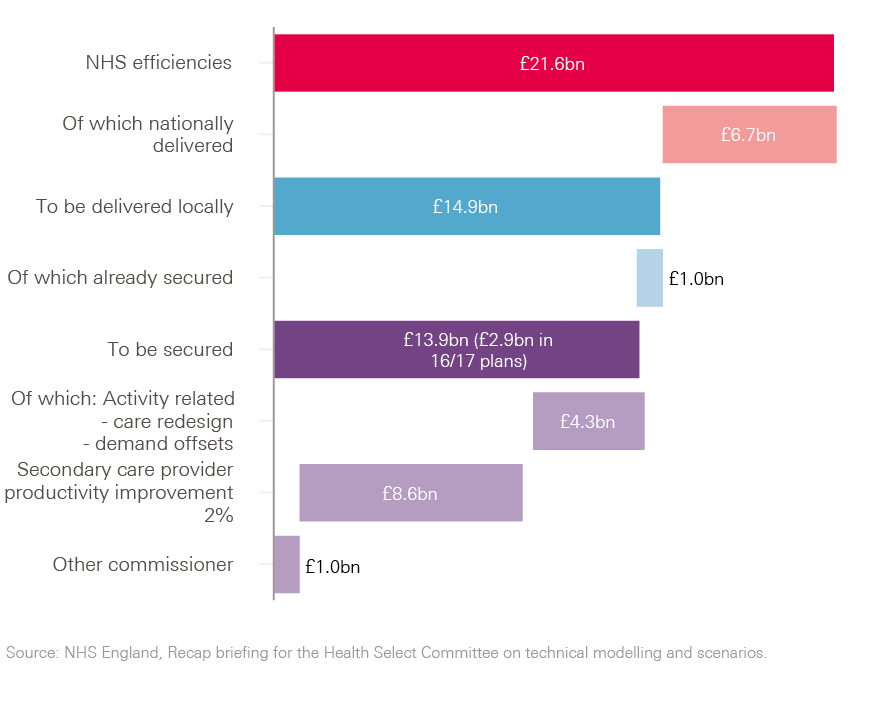

The FYFV is seeking to deliver savings of £22bn across the NHS. Workforce issues underpin much of the approach to realising those savings. Figure 1 sets out NHS England’s breakdown of the £22bn of savings. Almost £7bn is to be delivered nationally – principally through continued pay restraint. Capping NHS pay increases to 1% a year until 2019 is the largest single element of this national contribution to efficiency. The remaining £15bn of savings are to come from the NHS locally. Of this, £8.6bn needs to be delivered through improvements to the productivity of secondary care providers (mainly acute hospitals).

Figure 1: Sources of the proposed £22bn in efficiency savings as at the beginning of 2016/17

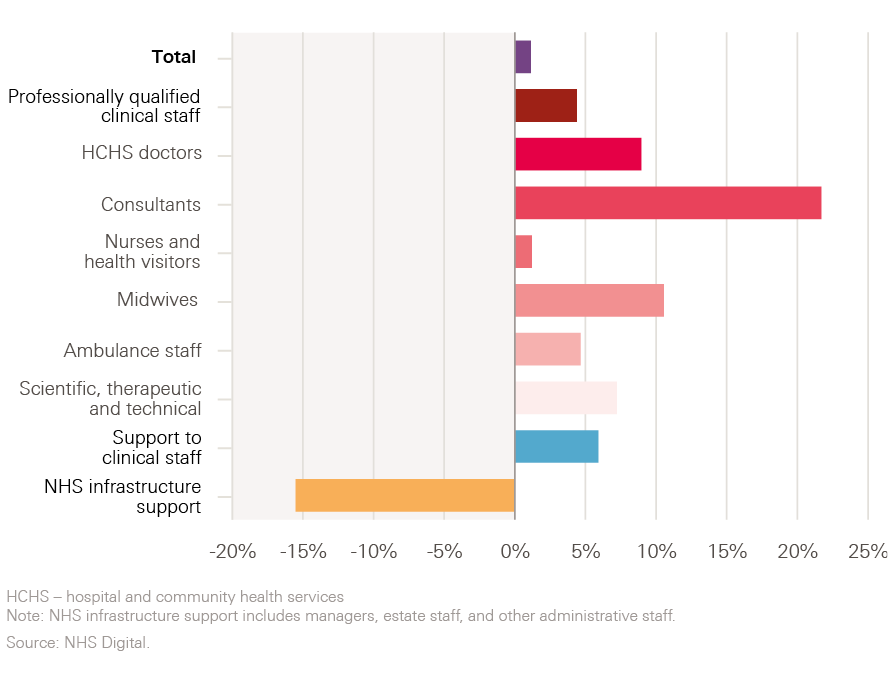

Figure 2 shows how the staffing of the NHS has changed over the first six years of the NHS’s decade of austerity (2010–2015). The overall number of staff employed by the NHS is broadly unchanged and has not kept pace with growth in activity.

Figure 2: Change in the number of full-time equivalent staff by occupational group, March 2010–2016

Although aggregate total numbers of staff have been broadly constant, the NHS in England has seen a substantial shift in the mix of staff groups employed by the NHS through this period. Infrastructure support staff numbers have fallen sharply so that the NHS has an increased proportion of clinical staff. Within the clinical staff category, the number of full-time equivalent consultants has increased by more than a fifth over six years, while the number of nurses has risen by just over 1%.

Pay restraint and reductions in headcount for groups such as infrastructure staff have been important planks for achieving financial balance over recent years, but they do not represent a long-term strategy to achieving sustainability or delivering change. Research in the Health Foundation’s recent report, A year of plenty?, found that this rapid change in skill mix has been associated with falling productivity in NHS acute hospitals. The research estimated labour productivity in 150 acute hospital trusts between 2009/10 and 2015/16 and looked at the productivity of consultants specifically. It found that labour productivity for all staff groups fell by an annual average of 0.7% and the productivity of consultants by 2.3% a year (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Annual change in consultant and all staff labour productivity in 150 NHS hospitals, 2009/10–2015/16 (%)

All 44 local areas in England have now produced STPs, which set out how they will transform services while achieving financial balance over the period to 2020/21. The King’s Fund has analysed all 44 plans and found that workforce issues figure in the plans in a variety of ways. Firstly, some areas are focused on tackling staff shortages. There are stated ambitions to reduce staff sickness and reliance on agency workers. More fundamentally, many STPs are seeking to significantly shift the balance of services, with major staffing implications. The King’s Fund report that the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire STP proposes changes that suggest a 12% reduction in numbers of band 5 nurses and similar roles, while at the same time proposing a 24% increase in the community and primary care workforce over the next five years. Other STPs are seeking to create new roles that span boundaries between staff groups across health and social care. Some STPs are beginning to consider how to use the apprentice levy to create new opportunities for local populations. Although many STPs have some interesting and ambitious proposals for workforce, it is still not clear how these ambitions will be supported by national workforce planning and policy decisions to have any impact by 2020/21.

The FYFV was published in October 2014 and set out the ambition to shift services to primary and community-based care. While funding for general practice is planned to increase by 2.8% a year in real terms from 2015/16 to 2020/21, GP capacity remains a real issue. The number of full-time equivalent GPs working for the NHS fell by 3% between September 2014 and September 2016. Similarly, the number of community health nurses has decreased by 14% since 2009.

A year of plenty? reinforces the need for integrated, whole system workforce planning. It finds that hospitals with a higher proportion of nurses have higher consultant productivity. Increasing the proportion of nurses in a hospital by 4% was associated with 1% more activity per consultant. A more balanced rise in staff numbers among different staff groups may ensure that the NHS uses consultants’ skills effectively. The government recently announced that it would further expand the medical workforce with 1,500 more medical student places over the coming years. This was in response to concerns about the NHS’s reliance on overseas-trained doctors. But this could have been an opportunity to look at the impact of Brexit on the training needs for all staff groups and make sure that the future supply of NHS staff is balanced between staff groups. As the NHS Pay Review Body (NHSPRB) highlighted in its 2017 report, almost a third (32%) of new nurse registrations in 2013/14 were by people from other EU countries.

In April 2017, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Long-Term Sustainability of the NHS concluded that the lack of a comprehensive, national long-term strategy to secure the appropriately skilled, trained and committed NHS and care system workforce is the biggest internal threat to the sustainability of the NHS.

The March 2017 Budget, and the accompanying economic forecast from the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), highlights that the financial context for NHS transformation is unlikely to change soon. The economic forecast projects public sector net borrowing of 0.7% of GDP at the end of the decade. If the government is to achieve fiscal balance in the next decade there will need to be a further period of public spending restraint and/or tax increases beyond the current spending review period.

Given the centrality of pay and nursing numbers to the NHS’s workforce, financial and service sustainability we have identified two particular issues that merit immediate consideration: NHS pay and nurse staffing. We have analysed these in more detail in pressure point supplements, but summarise the key points here. These pressure points reflect issues that have had recent national policy attention, but where there is continuing concern.

† Available to download from www.health.org.uk/publication/year-of-plenty

NHS pay

The NHS is heavily reliant on pay restraint to ensure that constrained finances do not have a negative impact on quality of care or access to services. This means that in recent years funding has trumped staffing – even if both the secretary of state and the chief executive of NHS England have said in recent months that the NHS needs more health professionals. Almost a quarter of the efficiency savings required to deliver the FYFV will come from holding pay bill growth below historic average earnings growth – and less than the underlying pressures on the system. This will be achieved by continuing to implement the government’s 1% public sector pay cap to 2019/20 and through reducing spending on agency staffing, which has been a substantial source of financial pressures over recent years.

On the back of commitments to workforce pay in the 2000 NHS Plan, earnings in the NHS rose in real terms between 2000 and 2010, with growth outpacing the increased earnings of workers in the rest of the economy. Since then the picture has been quite different and NHS earnings have consistently fallen short of inflation (consumer price index (CPI)). Between 2010 and 2017 the real (inflation-adjusted) value of health and social care staff’s pay has fallen by 6% (while in the economy as a whole it has fallen by only 2%).

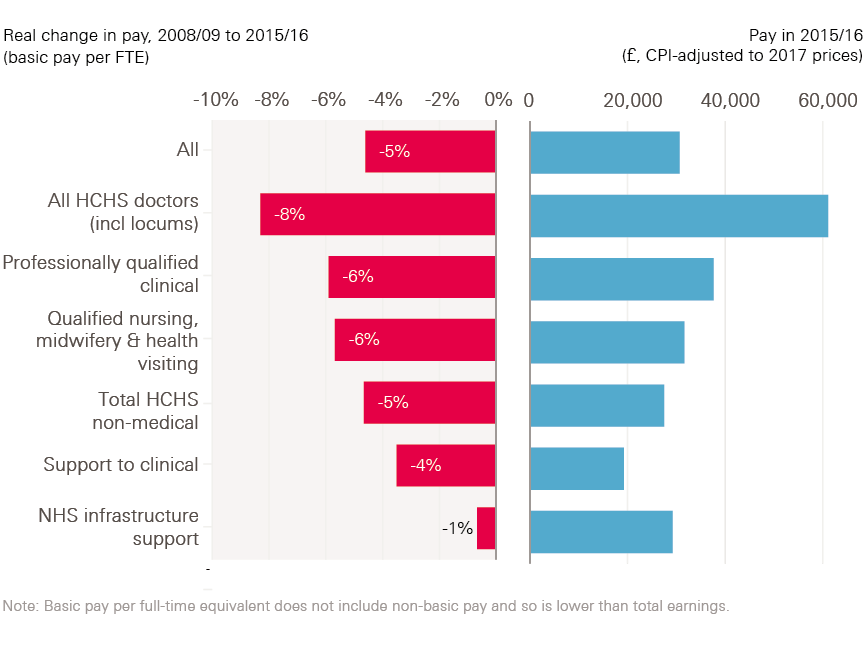

Within the NHS, the size of the real pay cut since 2008/09 varies: it is 6% for midwives and 8% for doctors. As this is basic pay per full-time equivalent, some of this may be a result of more staff joining certain staff groups at the bottom of pay bands. The real pay cut also varies by individual, due to factors such as pay progression (see Figure 4).

A number of changes to the tax and benefit system mean that the same gross basic pay may result in different take-home pay. The estimated take-home pay for someone at the top of the entry level nurse or midwife pay band (band 5) has increased by just £500 in cash terms between 2011/12 and 2016/17. This is a fall of 5% in real terms (adjusting for CPI).

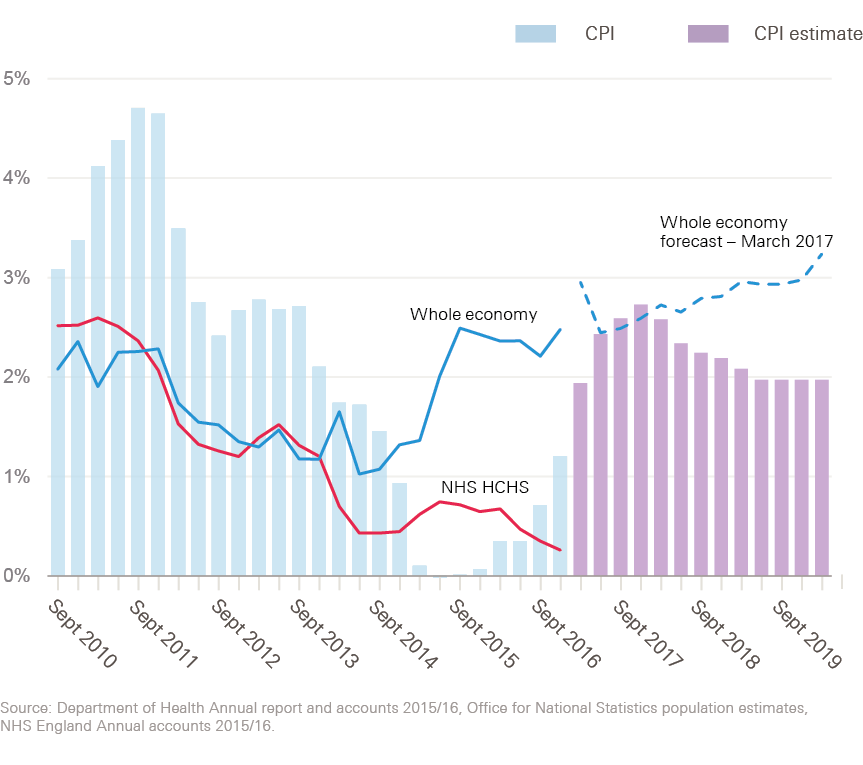

The OBR expects the rest of the economy to continue its earnings recovery (although less emphatically than it expected a year ago) and inflation to increase (more dramatically than it expected a year ago). This is a worrying combination for a health service that is committed to a 1% per year pay cap rise: increasing inflation means wages will continue to fall in real terms, while the private sector wage recovery means careers in health and social care will become relatively less appealing.

This exacerbates an existing problem, with private sector weekly earnings at 87% of those in the public sector in 2016 – the highest they’ve been for a number of years (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Real change in basic pay per full-time equivalent by staff group, 2008/09–2015/16

Figure 5: Pay and inflation, 2010–2020

In its recent report, the NHSPRB, working within the government’s pay policy, has recommended that all Agenda for Change pay scales are increased by 1% from April 2017. This covers most non-medical staff employed by the NHS. The Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration also recommended that pay scales for salaried doctors and dentists are increased by 1% in 2017/18 and that pay for independent contractor GPs and dentists, net of expenses, increases by 1%.

The 1% pay scale uplift compares to inflation estimates for 2017 of 2.3% when measured by CPI, and 3.2% when measured by the retail price index (RPI). Taking into account inflation forecasts and the pay policy for the rest of the decade, the NHSPRB calculates that, in real terms, NHS non-medical pay will have been cut by 12% (CPI) or 20% (RPI) over the decade from 2010/11 to 2020/21.

The NHSPRB report concludes:

‘It is clear that current public sector pay policy is coming under stress. There are significant supply shortages in a number of staff groups and geographical areas. There are widespread concerns about recruitment, retention and motivation that are shared by employers and staff side alike. Inflation is set to increase during 2017 compared to what was forecast leading to bigger cuts in real pay for staff than were anticipated in 2015, when current public sector pay policy was announced by the new UK Government. Local pay flexibilities to address recruitment and retention issues are not being used to alleviate the very shortages they were designed to address. Our judgement is that we are approaching the point when the current pay policy will require some modification, and greater flexibility within the NHS.’

NHS policymakers, and governments in the UK, cannot just focus on national pay bill control or on local flexibility and productivity improvement – they must address both. The review body approach (which is at the core of the NHS pay system) is under stress, but still has potential. It has shown itself to be an independent and objective mechanism for NHS pay determination. The stress it is under is externally imposed, rather than a sign of internal dissonance or lack of relevance. At national level there is need to prepare the pay determination system for the ‘end of the freeze’ of national pay constraint, currently timed by government until at least 2020. This will be more than 15 years after the last major reforms to NHS pay were introduced with Agenda for Change and new contracts for consultants and GPs. These previous major pay reforms were instigated after years of failure to modernise NHS pay and tackle some of the key underlying problems in the system (equal pay, relative earnings of different staff groups, inadequate career structures, etc). The lesson of the experience of the first 60 years of NHS pay reform is that boom and bust approaches to pay do not address underlying workforce challenges and can in fact reinforce them.

This means that at national level there is a need to prepare for the ‘end of the freeze’ of national pay constraint. Without adequate preparation, the risk is that pent-up demand from staff will understandably lead only to another cycle of ‘catch up’, followed again by the repeated risk of relative decline. The time is right to assess the options on how best to determine the total reward package for NHS staff, and decide if the current system continues to be fit for purpose, if it requires some alteration, or if it is time for substantial change. NHS pay is funded by UK governments, review body recommendations are implemented (or not) by UK governments, and the current national pay constraint has been imposed by UK governments. It is UK governments that must take the lead on ensuring that the NHS pay system is fit for purpose.

By 2020, NHS staff will have had a decade of falling real pay and little – if any – scope for reform to allow the pay system to respond to wider labour market changes. The ‘national living wage’ will also have impacted on pay differentials between staff. The NHSPRB has already raised this point in respect of NHS staff in Scotland. Moreover, while pay structures and levels have been ‘frozen’, other aspects of NHS staff reward packages have been subject to significant reform – most notably pensions and bursaries for training.

It is important not to take a narrow or short-term view of the NHS pay determination system. As noted, its outcome is a major and highly visible element of the contract between the organisation and the health worker, and it can be a powerful policy lever. It should be aligned with an overall agreed approach to NHS workforce development. If 2020 is to be the end of pay constraint, then now is the time to begin a national debate about what system should be in place afterwards, in order to either reach endorsement that the current approach, with or without modification, continues to be fit for purpose, or if a new approach is required to sustain staffing levels, motivation and productivity, and to address regional labour market variations. A starting point would be a structured national policy dialogue between key stakeholders and independent experts to analyse trends and assess options. To give impetus to this review, it should be aligned with a clear statement by UK governments about when the ‘freeze’ on public sector pay will end. The House of Lords Select Committee on the long-term sustainability of the NHS has also raised concern about the impact of prolonged pay restraint. It recommended that the government should commission an independent review of pay policy with a specific focus on the impact of pay on the morale and retention of health and care staff. The Select Committee called for the pay review bodies to be involved in this review.

Alongside preparing for the end of nationally imposed pay restraint, the NHS also needs to make more progress on shorter-term improvements.

Linking pay to productivity, so that the NHS workforce’s incentives are better aligned with those of the system, is one area that needs consideration. Weaknesses in previous attempts to link pay and productivity/performance of health workers have been the focus on individual performance, often of doctors,, and the emphasis on only financial incentives rather than on total reward. This ignores the team-based system of delivery, and multidisciplinary team ethos, that permeates the NHS. It also discounts the other factors that motivate people to work effectively in the NHS, such as participative decision making, the ability to deliver quality care, and access to training, development and career advancement.

Irrespective of decisions on longer-term NHS pay strategy, there is scope in the short term to:

- give greater emphasis to securing the maximum flexibilities from the current system

- provide some ‘pump-priming’ support for local pilots focusing on improved productivity and performance through incentives for effective team working.

What is needed are NHS trust-level or STP-level test sites that examine the potential for team-based incentive approaches. This would require ‘bundles’ of complementary local incentive policies to be developed with staff input, informed by the limited but growing international evidence base,,,,, and implemented with the specific intention of supporting sustained ‘high performance’ team working., Evaluation would focus on cost and output/outcome measures, in order to identify which approaches have greatest promise of sustained cost–benefit and productivity improvement.

As stressed in the accompanying supplement on NHS pay, there have been repeated reports that the current flexibilities within the NHS pay system are underused – the NHSPRB noted that the use of recruitment and retention premia is actually in decline. The DDRB also recommended that better use is made of existing pay flexibilities. Various reasons for this lack of use have been suggested. However, a rapid review of the currently available pay flexibilities, the extent of their use and evidence of their impact would be useful. This could inform policymakers about constraints on take-up that can be addressed immediately, whether there is a need for changes in funding and/or local capacity, or if there are current flexibilities that are not relevant or useful. Findings of the review could then be used to reform and recalibrate the available pay flexibilities and address identified constraints.

Nurse staffing

Following on from the report by Sir Robert Francis into the care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, published in 2013, national policy focus on staffing levels in the NHS in England has not been robust or consistent. The approach has been caught between concern about staffing levels (with the aim of assuring care is safe) and the need to contain staffing costs as part of the financial challenge. Increases in agency costs have been a main manifestation of this conflict. Despite the efforts to recruit more nurses following the Francis Inquiry, the percentage of nurses thinking that there are not enough staff at their organisation to do their job properly has stayed broadly stable since 2010 – at around 50%.

At a national level the NHS in England doesn’t have enough nurses, with a reported shortfall of 22,000 nurses specialising in caring for adult patients in 2015 – almost 10% of this workforce. Even under the most optimistic scenario for growth in the supply of nurses there is still projected to be a shortfall in 2020 (albeit reduced to 14,000 – 5.5% of the workforce). Under the more pessimistic national scenario, the shortfall in 2020 will be 38,000 nurses, equivalent to 15% of the workforce.

Figure 6: The shortfall of nurses specialising in caring for adult patients, 2015 and 2020

The March 2017 Next steps on the NHS five year forward view acknowledged that the NHS will need more registered nurses in 2020 than today, as will the social care system. However, the crisis in nursing numbers is likely to become more acute with the decision to leave the EU. One in three new nurses entering the UK register for the first time in 2015/16 had been previously registered in another EU country. In the NHS in England, 7% of nurses and health visitors are from other EU countries – and the number has increased by 85% since 2013 to 22,000, while the number without an EU nationality has increased by just 3%. Worryingly, the number of applications for nursing degrees from people from other EU countries is 25% lower this year than last year – the biggest decrease in any domicile group. Similarly, 3,500 nurses with EU nationality left the NHS in 2016 – twice as many as in 2014.

Given the pressure on numbers, ensuring that nurses are deployed well to support safe and efficient delivery of care is vital. There has not been a sustained direction for national policy on safe staffing and there has been limited progress in any national advice or guidance on how to determine safe staffing. This is because there needs to be local flexibility, but at the same time, there are very specific ‘top-down’ requirements on agency use. The approach to safe staffing in the recent draft staffing guidance for England (sent out for consultation, with responses currently being considered) emphasises local responsibilities, but highlights a lack of evidence to support implementation. It also lacks the level of specificity and more systematic, standardised approach now being put in place in the other three UK countries. This leaves England open to criticism that the current guideline-based approach does not, as yet, cover important areas, and does not favour the mandatory, legislation-based, or standardised systems being advocated in the other UK countries. It can ‘look’ relatively weak and incomplete in comparison. The pressure point supplement sets out more detail on the approaches to determining staffing levels being taken in the other countries of the UK.

If the NHS in England is to turn this apparent weakness into a potential strength – an approach based on local flexibility in nurse staffing decisions – then it will have to accept that the inevitable result will be greater variation in local staffing levels. Local autonomy of decision making will have to be supported, but shored up by necessary checks and balances to prevent any recurrence of a major quality failure linked to inadequate staffing. To ensure that this approach is effective, the NHS needs to focus on two critical enablers:

- It needs more effective local management capacity and responsiveness in analysing, determining, implementing and monitoring ‘what is safe’.

- It will also need to make much more rapid progress in identifying and networking ‘what works’ in terms of local team-based safe staffing tools and approaches, and the effective use of local data and systems.

Critical to this is harnessing the potential of new technology to support better staffing decisions. This would also allow a much improved ‘line of sight’ for NHS trust boards so that they can be better informed in discharging their governance responsibilities related to safe staffing. As Lord Carter of Coles’ review of NHS operational efficiency has already identified, the NHS is not using information technology as well as it could for a range of staffing issues – his review highlighted the importance of e-rostering systems. Technological progress means that there can also be more emphasis on provision of timely, ‘live’ and easy-to-read data ‘dashboards’ and apps to support local decision making on staffing levels, based on a clearer assessment of workflows and workload variations. There are already examples of such approaches being used successfully in both the UK and elsewhere.,

However good the new tools, systems and dashboards, they can only be effective when local staff fully understand the scope and benefits of their use, and can drive the process of turning analysis and live data into immediate responses. This is in part about empowering people to make staffing decisions, but also relates to providing them with appropriate training and development, both in the practical aspects of using tools and in the ability to optimise their application. NHS organisations in England make use of a range of approaches to determining staffing levels. Not all are, or can be, well aligned with systems required for staff rostering, scheduling and identifying the need to deploy temporary additional staff. This link must be made and sustained for a fully effective approach to determining safe staffing levels.

As the FYFV and STPs make clear, the NHS will need to transform care in ways that will require staff groups to work together in collaborative multidisciplinary teams in ways that cross role and organisational boundaries. The 44 STPs expose a further disconnect between local aspirations for workforce change and the lack of an enabling national policy and planning framework. Silo workforce planning is unlikely to meet the needs of the new models of care. Some of the tools and approaches – and most of the limited evidence – available to support decisions on safe staffing focus only on registered nurses, and only on hospital-based adult acute care. Several areas of care identified as policy priorities in the NHS in England, including community care and mental health, are virtually tool- and evidence-free. And while registered nurses are central to the safe delivery of care in virtually all care environments, they are not usually the only staff working to ensure safe care. There is a need to accelerate the pace of coverage to build up evidence on ‘what works’ for safe staffing across these important but underexamined areas – and to reinforce that tools and approaches must give consideration to team-based delivery, maintaining an effective skill mix as part of the overall process of determining safe staffing.

There is clear scope for greater collaboration across the UK countries on some aspects of nurse staffing. For example, there appears to be no reason why the NHS in England could not collaborate with Wales and Scotland on the testing and endorsement of staffing tools, given that Scotland has reportedly now developed an almost full suite. (As yet England only endorses three, and these are only for acute care and were approved several years ago. NICE has separately endorsed a fourth, in April 2017) In addition, there is scope to compare and assess the impact of these different safe staffing tools and systems as they are fully implemented. This will provide an opportunity to share experiences across UK borders and assess the strengths and weaknesses of the different approaches to determining safe staffing. This could be a joint approach that would give economies of scale and avoid unnecessary repetition of evaluation.

Conclusion

The Five year forward view sets out an ambitious programme to transform the NHS in England. Realising that ambition in a period of unprecedented financial constraint is always going to be challenging, but without the engagement of the million-plus people who work in the NHS it will be impossible. The NHS still has no overarching strategy for its workforce. Piecemeal policymaking, however well-intentioned any individual initiative might be, is not serving the NHS well. 2016/17 has been a year of enormous service and financial pressure for the NHS and things are unlikely to get any easier for the foreseeable future. The NHS will not be able to move forward to deliver sustained efficiency improvements and transform services without a serious examination of its approach to pay and the way it plans and uses its nursing workforce across the system.

References

- Tariff document for 2017/18.

- Lafond S, Charlesworth A, Roberts A. A year of plenty? An analysis of NHS finances and consultant productivity. London: Health Foundation, 2017. Available from: www.health.org.uk/publication/year-of-plenty

- Ham C, Alderwick H, Dunn P, McKenna H. Delivering sustainability and transformation plans: From ambitious proposals to credible plans. London: The King’s Fund, 2017. Available from: www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/STPs_proposals_to_plans_Kings_Fund_Feb_2017_0.pdf

- NHS Pay Review Body Thirtieth Report, 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/nhs-pay-review-body

- House of Lords Select Committee on the Long-term Sustainability of the NHS. The Long-term Sustainability of the NHS and Adult Social Care. 2017.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/spring-budget-2017

- Department of Health. NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: HMSO, 2000.

- NHS Pay Review Body Thirtieth Report, 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/nhs-pay-review-body

- Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration Forty-Fifth Report, 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-body-on-doctors-and-dentists-remuneration-45th-report-2017

- Petersen L, Woodard L, Urech T, Daw C, Supicha S. Does Pay-for-Performance Improve the Quality of Health Care? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(4).

- Ray K, Foley B, Tsang T, Walne D, Bajorek Z. A review of the evidence on the impact, effectiveness and value for money of performance-related pay in the public sector. London: The Work Foundation, 2014.

- Misfeldt R, Linder J, Lait J, Hepp S, Armitage G, Jackson K, Suter E. Incentives for improving human resource outcomes in health care: overview of reviews. J Health Services Research and Policy. 2014;19(1):52–61. doi:10.1177/1355819613505746.

- Blumenthal DM, Song Z, Jena AB, Ferris T. Guidance for Structuring Team-Based Incentives in Health Care. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2013;19(2):e64–e70.

- Bartel AP, Beaulieu ND, Phibbs CS, Stone PW. Human capital and productivity in a team environment: evidence from the healthcare sector. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2014;6(2):231.

- Lehtovuori T, Kauppila T, Kallio J, Raina M, Suominen L, Heikkinen AM. Financial team incentives improved recording of diagnoses in primary care: a quasi-experimental longitudinal follow-up study with controls. BMC research notes. 2015;8(1):668.

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospital Gainsharing Demonstration. USA: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015. Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Medicare-Hospital-Gainsharing

- Kretzschmar R, Gazdick C, Magno C, SanAgustin C. Pulling together: Team-based performance sharing. Nursing management. 2016;47(4):14–15.

- Garman AN, McAlearney AS, Harrison MI, Song PH, McHugh M. High-performance work systems in health care management, part 1: development of an evidence-informed model. Health care management review. 2011;36(3):201–213.

- Chuang E, Dill J, Morgan JC, Konrad TR. A Configurational Approach to the Relationship between High-Performance Work Practices and Frontline Health Care Worker Outcomes. Health Services Research. 2012;47:1460–1481.

- NHS Pay Review Body Thirtieth Report, 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/nhs-pay-review-body

- Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationery Office, 2013.

- NHS Pay Review Body Thirtieth Report, 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/nhs-pay-review-body

- NHS Digital. NHS Leavers and Staff in Post: headcount by nationality group. NHS Digital, 2017.

- UCAS. 2017 cycle applicant figures – January deadline. Available from: https://www.ucas.com/corporate/data-and-analysis/ucas-undergraduate-releases/2017-cycle-applicant-figures-%E2%80%93-january-deadline

- NHS Digital. NHS Leavers and Staff in Post: headcount by nationality group. NHS Digital, 2017.

- Lord Carter of Coles. Operational productivity and performance in English NHS acute hospitals: Unwarranted variations. London: Department of Health, 2016

- http://fabnhsstuff.net/category/safe-staffing

- Lawless J. Safe Staffing: The New Zealand Public Health Sector Experience. Expert Paper 1: Expert testimony presented to the Safe Staffing Advisory Committee. London: NICE, 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sg1/documents/safe-staffing-guideline-consultation11

- Tuominen O, Lundgren-Laine H, Kauppila W, Hupli M, Salanterä S. A real-time Excel-based scheduling solution for nursing staff reallocation. Nursing Management. 2016;23(6):22–29. doi: 10.7748/nm.2016.e1516.